Abstract

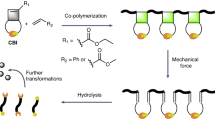

Customizing the toughness of polymer networks independently of their chemical composition and topology remains an unsolved challenge. Traditionally, polymer network toughening is achieved by using specialized monomers or solvents or adding secondary networks/fillers that substantially alter the composition and may limit applications. Here we report a class of force-responsive molecules—tetrafunctional cyclobutanes (TCBs)—that enable the synthesis of single-network end-linked gels with substantially decreased or increased toughness, including unusually high toughness for dilute end-linked gels, with no other changes to network composition. This behaviour arises from stress-selective force-coupled TCB reactivity when stress is imparted from multiple directions simultaneously, which traditional bifunctional mechanophores cannot access. This molecular-scale mechanoreactivity translates to bulk toughness through a topological descriptor, network strand continuity, that describes the effect of TCB reactivity on the consequent local network topology. TCB mechanophores and the corresponding concepts of stress-selective force-coupled reactivity and strand continuity offer design principles for tuning the toughness of simple yet commonly used single-network gels.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$32.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $21.58 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

All data are available in the main text, in the Supplementary Information or via Figshare at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.29973850 (ref. 71). Crystallographic data for the structure reported in this Article have been deposited at the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre, under deposition number CCDC 2448803 (CB-C2). Copies of the data can be obtained free of charge at https://www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/structures.

Code availability

The computational codes for this work are available via Github at https://github.com/olsenlabmit/Cyclobutane-junctions-network-toughnening.

References

Zhao, X. et al. Soft materials by design: unconventional polymer networks give extreme properties. Chem. Rev. 121, 4309–4372 (2021).

Gu, Y., Zhao, J. & Johnson, J. A. Polymer networks: from plastics and gels to porous frameworks. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59, 5022–5049 (2020).

Thomas, A. G. Rupture of rubber. II. The strain concentration at an incision. J. Polym. Sci. 18, 177–188 (1955).

Lake, G. J. & Thomas, A. G. The strength of highly elastic materials. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. A 300, 108–119 (1967).

Akagi, Y., Sakurai, H., Gong, J. P., Chung, U. & Sakai, T. Fracture energy of polymer gels with controlled network structures. J. Chem. Phys. 139, 144905 (2013).

Sun, J.-Y. et al. Highly stretchable and tough hydrogels. Nature 489, 133–136 (2012).

Hua, M. et al. Strong tough hydrogels via the synergy of freeze-casting and salting out. Nature 590, 594–599 (2021).

Wang, M. et al. Glassy gels toughened by solvent. Nature https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-024-07564-0 (2024).

Wang, Z. et al. Toughening hydrogels through force-triggered chemical reactions that lengthen polymer strands. Science 374, 193–196 (2021).

Han, L. et al. Mussel-inspired adhesive and tough hydrogel based on nanoclay confined dopamine polymerization. ACS Nano 11, 2561–2574 (2017).

Kim, J., Zhang, G., Shi, M. & Suo, Z. Fracture, fatigue, and friction of polymers in which entanglements greatly outnumber cross-links. Science 374, 212–216 (2021).

Gong, J. P. Why are double network hydrogels so tough?. Soft Matter https://doi.org/10.1039/b924290b (2010).

Ouchi, T., Wang, W., Silverstein, B. E., Johnson, J. A. & Craig, S. L. Effect of strand molecular length on mechanochemical transduction in elastomers probed with uniform force sensors. Polym. Chem. 14, 1646–1655 (2023).

Bowser, B. H. et al. Single-Event Spectroscopy and Unravelling Kinetics of Covalent Domains Based on Cyclobutane Mechanophores. J. Am. Chem. Soc. https://doi.org/10.1021/jacs.1c02149 (2021).

Slootman, J. et al. Quantifying rate- and temperature-dependent molecular damage in elastomer fracture. Phys. Rev. X https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevX.10.041045 (2020).

Clough, J. M., van der Gucht, J. & Sijbesma, R. P. Mechanoluminescent imaging of osmotic stress-induced damage in a glassy polymer network. Macromolecules 50, 2043–2053 (2017).

Wang, S. et al. Facile mechanochemical cycloreversion of polymer cross-linkers enhances tear resistance. Science 380, 1248–1252 (2023).

Yokochi, H. et al. Sacrificial mechanical bond is as effective as a sacrificial covalent bond in increasing cross-linked polymer toughness. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 23794–23801 (2023).

Wang, S. et al. Mechanism dictates mechanics: a molecular substituent effect in the macroscopic fracture of a covalent polymer network. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143, 3714–3718 (2021).

DeForest, C. A., Polizzotti, B. D. & Anseth, K. S. Sequential click reactions for synthesizing and patterning three-dimensional cell microenvironments. Nat. Mater. 8, 659–664 (2009).

Ohnsorg, M. L. et al. Nonlinear elastic bottlebrush polymer hydrogels modulate actomyosin mediated protrusion formation in mesenchymal stromal cells. Adv. Mater. n/a, 2403198 (2024).

Blatchley, M. R. & Anseth, K. S. Middle-out methods for spatiotemporal tissue engineering of organoids. Nat. Rev. Bioeng. 1, 329–345 (2023).

Wallace, D. G. et al. A tissue sealant based on reactive multifunctional polyethylene glycol. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 58, 545–555 (2001).

Hoshi, S. et al. In vivo and in vitro feasibility studies of intraocular use of polyethylene glycol–based synthetic sealant to close retinal breaks in porcine and rabbit eyes. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 56, 4705–4711 (2015).

McTiernan, C. D. et al. LiQD cornea: pro-regeneration collagen mimetics as patches and alternatives to corneal transplantation. Sci. Adv. 6, eaba2187 (2020).

Xin, S., Chimene, D., Garza, J. E., Gaharwar, A. K. & Alge, D. L. Clickable PEG hydrogel microspheres as building blocks for 3D bioprinting. Biomater. Sci. 7, 1179–1187 (2019).

Gu, Y., Zhao, J. & Johnson, J. A. A (macro)molecular-level understanding of polymer network topology. Trends Chem. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trechm.2019.02.017 (2019).

Tsuji, Y., Li, X. & Shibayama, M. Evaluation of mesh size in model polymer networks consisting of tetra-arm and linear poly(ethylene glycol)s. Gels 4, 50 (2018) .

Ribas-Arino, J., Shiga, M. & Marx, D. Understanding Covalent Mechanochemistry. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 48, 4190–4193 (2009).

Zhang, H. et al. Multi-modal mechanophores based on cinnamate dimers. Nat. Commun. 8, 1147 (2017).

Ding, S. et al. Bicyclo[2.2.0]hexene: a multicyclic mechanophore with reactivity diversified by external forces. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 6104–6113 (2024).

Chen, Z. et al. Stress-dependent multicolor mechanochromism in epoxy thermosets based on rhodamine and diaminodiphenylmethane mechanophores. Macromolecules 55, 2310–2319 (2022).

Wang, J. et al. Counting loops in sidechain-crosslinked polymers from elastic solids to single-chain nanoparticles. Chem. Sci. 10, 5332–5337 (2019).

Zhong, M., Wang, R., Kawamoto, K., Olsen, B. D. & Johnson, J. A. Quantifying the impact of molecular defects on polymer network elasticity. Science 353, 1264–1268 (2016).

Wang, R., Alexander-Katz, A., Johnson, J. A. & Olsen, B. D. Universal cyclic topology in polymer networks. Phys. Rev. Lett. 116, 188302 (2016).

Lin, Y., Kouznetsova, T. B., Foret, A. G. & Craig, S. L. Solvent polarity effects on the mechanochemistry of spiropyran ring opening. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 3920–3925 (2024).

Simeral, L. & Amey, R. L. Dielectric properties of liquid propylene carbonate. J. Phys. Chem. 74, 1443–1446 (1970).

Maryott, A. A. Table of Dielectric Constants of Pure Liquids. Circular of the Bureau of Standards No. 514 (National Institute of Standards and Technology, 1951).

Gusev, A. A. Numerical estimates of the topological effects in the elasticity of Gaussian polymer networks and their exact theoretical description. Macromolecules 52, 3244–3251 (2019).

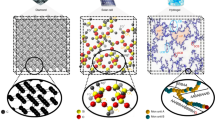

Arora, A., Lin, T.-S. & Olsen, B. D. Coarse-grained simulations for fracture of polymer networks: stress versus topological inhomogeneities. Macromolecules 55, 4–14 (2022).

Beech, H. K. et al. Reactivity-guided depercolation processes determine fracture behavior in end-linked polymer networks. ACS Macro Lett. 12, 1685–1691 (2023).

Kawamoto, K., Zhong, M., Wang, R., Olsen, B. D. & Johnson, J. A. Loops versus branch functionality in model click hydrogels. Macromolecules 48, 8980–8988 (2015).

Lin, T.-S., Wang, R., Johnson, J. A. & Olsen, B. D. Topological structure of networks formed from symmetric four-arm precursors. Macromolecules 51, 1224–1231 (2018).

Lin, S., Ni, J., Zheng, D. & Zhao, X. Fracture and fatigue of ideal polymer networks. Extreme Mech. Lett. 48, 101399 (2021).

Wang, S., Panyukov, S., Craig, S. L. & Rubinstein, M. Contribution of unbroken strands to the fracture of polymer networks. Macromolecules 56, 2309–2318 (2023).

Wang, J. et al. A remote stereochemical lever arm effect in polymer mechanochemistry. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 15162–15165 (2014).

Sun, T. L. et al. Physical hydrogels composed of polyampholytes demonstrate high toughness and viscoelasticity. Nat. Mater. 12, 932–937 (2013).

Jiang, L. et al. Highly stretchable and instantly recoverable slide-ring gels consisting of enzymatically synthesized polyrotaxane with low host coverage. Chem. Mater. 30, 5013–5019 (2018).

Liu, C. et al. Tough hydrogels with rapid self-reinforcement. Science 372, 1078–1081 (2021).

Zhang, E., Bai, R., Morelle, X. P. & Suo, Z. Fatigue fracture of nearly elastic hydrogels. Soft Matter 14, 3563–3571 (2018).

Liu, J. et al. Polyacrylamide hydrogels. II. Elastic dissipater. J. Mech. Phys. Solids 133, 103737 (2019).

Lin, S. et al. Anti-fatigue-fracture hydrogels. Sci. Adv. 5, eaau8528 (2019).

Barney, C. W. et al. Fracture of model end-linked networks. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 119, e2112389119 (2022).

Arora, A. et al. Fracture of polymer networks containing topological defects. Macromolecules 53, 7346–7355 (2020).

Liu, C. et al. Unusual fracture behavior of slide-ring gels with movable cross-links. ACS Macro Lett. 6, 1409–1413 (2017).

Liu, C. et al. Direct observation of large deformation and fracture behavior at the crack tip of slide-ring gel. J. Electrochem. Soc. 166, B3143 (2019).

Becke, A. D. Density-functional thermochemistry. III. The role of exact exchange. J. Chem. Phys. 98, 5648–5652 (1993).

Lee, C., Yang, W. & Parr, R. G. Development of the Colle–Salvetti correlation-energy formula into a functional of the electron density. Phys. Rev. B: Condens. Matter 37, 785–789 (1988).

Stephens, P. J., Devlin, F. J., Chabalowski, C. F. & Frisch, M. J. Ab Initio calculation of vibrational absorption and circular dichroism spectra using density functional force fields. J. Phys. Chem. 98, 11623–11627 (1994).

Chai, J.-D. & Head-Gordon, M. Long-range corrected hybrid density functionals with damped atom–atom dispersion corrections. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 10, 6615–6620 (2008).

Lange, A. W. & Herbert, J. M. A smooth, nonsingular, and faithful discretization scheme for polarizable continuum models: the switching/Gaussian approach. J. Chem. Phys. 133, 244111 (2010).

Rivlin, R. S. & Thomas, A. G. Rupture of rubber. I. Characteristic energy for tearing. J. Polym. Sci. 10, 291–318 (1953).

Neese, F. Software update: The ORCA program system—Version 5.0. WIREs Comput. Mol. Sci. 12, e1606 (2022).

Caldeweyher, E., Mewes, J.-M., Ehlert, S. & Grimme, S. Extension and evaluation of the D4 London-dispersion model for periodic systems. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 22, 8499–8512 (2020).

Eckert, F., Pulay, P. & Werner, H.-J. Ab initio geometry optimization for large molecules. J. Comput. Chem. 18, 1473–1483 (1997).

Neese, F. Definition of corresponding orbitals and the diradical character in broken symmetry DFT calculations on spin coupled systems. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 65, 781–785 (2004).

Bitzek, E., Koskinen, P., Gähler, F., Moseler, M. & Gumbsch, P. Structural relaxation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 97, 170201 (2006).

Zhurkov, S. N., Zakrevskyi, V. A., Korsukov, V. E. & Kuksenko, V. S. Mechanism of submicrocrack generation in stressed polymers. J. Polym. Sci. Polym. Phys. 10, 1509–1520 (1972).

Zhurkov, S. N. & Korsukov, V. E. Atomic mechanism of fracture of solid polymers. J. Polym. Sci. Polym. Phys. Ed. 12, 385–398 (1974).

Wang, R., Johnson, J. A. & Olsen, B. D. Odd–Even effect of junction functionality on the topology and elasticity of polymer networks. Macromolecules 50, 2556–2564 (2017).

Herzog-Arbeitman, A. Data for ‘Tetrafunctional cyclobutanes tune toughness via network strand continuity’. Figshare https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.29973850 (2025).

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the MIT SuperCloud and Lincoln Laboratory Supercomputing Center for providing HPC resources that have contributed to the research results reported within this paper. This work was supported by the NSF Center for the Chemistry of Molecularly Optimized Networks (MONET), CHE-2116298. A.H.-A. acknowledges the MIT Martin Family Fellowship for funding. The authors gratefully acknowledge M. Kim and X. Zheng for integrating BigSMILES notation for the polymers within this work. Funding for this study was provided by the NSF Center for the Chemistry of Molecularly Optimized Networks (MONET), CHE-2116298 and the MIT Martin Family Society of Fellows for Sustainability (A.H.-A.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.H.-A., I.K., B.D.O., J.A.J. and S.L.C. conceptualized the studies. A.H.-A. and J.L. synthesized materials and fabricated testing samples. A.H.-A. and S.W. conducted mechanical testing and other characterizations. EFEI studies were conducted by I.K. and supervised by H.J.K. Network tensile simulation and analysis was done by D.S., J.C. and supervised by B.D.O. Single-crystal X-ray diffraction and analysis was done by P.M. J.A.J., B.D.O., S.L.C. and H.J.K. acquired funding. A.H.-A. and J.A.J. drafted and edited the manuscript; all authors edited and discussed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare the following competing interests: J.A.J., S.W. and A.H.A. are inventors listed on a patent, International Application Number PCT/US2024/033425, owned by MIT and Duke University, which describes the synthesis and use of the junctions described above and other related molecules. All other authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Chemistry thanks Derek Kiebala, Yun Liu, Melissa Pasquinelli and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Extended Data Fig. 1 Control junction, and construction of a control end-linked network, Control-G.

For Detailed conditions, see Methods. PC: propylene carbonate.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Simulated CB-C2, CB-C1, and CB-ether model junction mechanochemical reaction barriers.

Top: simulated barriers to cycloelimination and C–O heterolysis under external force. Right, Inset: CB-ether junction structure as synthesized. Bottom: mechanochemical reactions simulated. The simulated transition state for C–O heterolysis for CB-C1 under cis-1,2-stress is shown, illustrating the intact cyclobutane ring even under the most favourable stress-orientation for [2 + 2]cycloelimination.

Extended Data Fig. 3 Bulk characterization of TCB and Control gels.

Top left: FTIR spectra for gels, as prepared. Top right, Young’s moduli for all unnotched pure shear samples for each junction composition. Error bars show ±1 standard deviation, for n = 3 samples from a single gel sheet each. Bottom: representative rheology characterization (amplitude sweep, left; frequency sweep, right) for each gel composition.

Extended Data Fig. 4 Full stress–strain curves for determination of tearing energy in PC gels.

Notched and unnotched samples for all tested network chemistries. Unnotched samples are shaded darker.

Extended Data Fig. 5 Modulus, tearing energy, and full stress–strain curves for determination of tearing energy in MeOPh gels.

a) Frequency sweeps on as-synthesized MeOPh gels. b) Young’s modulus derived from tearing energy samples. Error bars show ±1 standard deviation, for n = 3 samples from a single gel sheet each. c) Full stress–strain curves for notched and unnotched samples of MeOPh gels. Replicates of unnotched samples were not shown for clarity. d) Tearing energy vs. critical stress values for the stress–strain curves in (c). Box-and-whisker plots, inset, show tearing energy measurements, with white lines indicating the median value and black lines showing the mean. Box edges show first and third quartile; whiskers denote data range. Each tearing energy value is derived samples (n = 4 for CB-C1 and Control; n = 3 for CB-C2) and cut from a single gel sheet to remove batch-to-batch variation.

Extended Data Fig. 6 EFEI calculated barriers for model junctions in aqueous contexts.

a) Barriers for all pathways in CB-C1 models. b) Barriers for relevant pathways in CB-C2 models. The cis 1,2 orientation has the lowest barrier to [2 + 2] cycloelimination, and the 1,3 orientation has the lowest barrier to C–O heterolysis, thus behaviour is qualitatively similar to PC gels. c) Barriers for all pathways in CB-C1 models. d) Barrier to C–C homolysis in the control model. In a)–c), darker lines denote [2 + 2] cycloelimination pathways; lighter lines denote C–O heterolysis.

Extended Data Fig. 7 Fluorescence microscopy imaging and quantification of damaged gels.

a, d, g, j), Overlayed brightfield and fluorescence images of twisted regions of gels after dyeing. An example gel after twisting is shown in Supplementary Fig. S3. b, e, h, k) Fluorescence images without brightfield images overlayed. Bright line patterns in (b) and (e) show CB-C2 activation in areas of damage. These patterns are faint in CB-C1 where ring-opening is discouraged and nonexistent in Control networks. c, f, i, l) Fluorescence intensity (quantified by mean grey value) along the dashed arrows shown in (a, d, g, j), respectively. Shaded regions in (c, f, I,l) indicate average background fluorescence ±1 standard deviation, measured on undamaged ends of the same samples, see Supplementary Fig. S3. (a–f) display CB-C2 fluorescence, (g–i) CB-C1, and (j–l) correspond to Control. Lines of high fluorescence only occur in regions buckled during twisting, and follow the warped curvature of the sample, for example the gel edge at the top of (a) and (b), consistent with CB-C2 activation as stress concentrates near geometric distortions. Razor-cut gel edges showed high but variable fluorescence. m) Reaction schematic for attachment of TAMRA to the olefin residues of activated TCBs. Mean grey values shown correspond to fluorescence intensity only. All images were captured using the same laser gain and exposure time for straightforward comparison.

Extended Data Fig. 8 Fluorescence microscopy imaging of hammered CB-C2-G.

Upper: brightfield and fluorescence images overlayed. Lower: fluorescence image. Laser settings were altered from images in Extended Data Fig. 7 to improve contrast and detail visibility.

Extended Data Fig. 9 Toughness measurements including CB-ether.

Measured tearing energies vs. critical stress (top) and toughnesses (work of fracture) vs. strain-at-break (bottom) for all tested networks including CB-ether. Other networks tested are shown for comparison. CB-ether-G tearing energy is statistically greater than Control-G networks (1-tailed t-test, \(p=0.002\)), but not from CB-C2-G (\(p=0.62\)). CB-ether-G toughness is statistically greater than Control-G and CB-C1-G networks (1-tailed t-test, \(p=0.015,p=0.024\), respectively). Box plots are shown with white lines indicating the median value and black lines showing the mean. Box edges show first and third quartile; whiskers denote data range. Each tearing energy value is derived from samples (n = 6 for CB-C1, CB-C2 and CB-ether; n = 7 for Control) cut from a single gel sheet. Toughness values are derived from n = 4 (2); 6(3); 9(4); 7(4) total replicates (number of biological replicates in parentheses), from left to right.

Extended Data Fig. 10 Comparison of toughness, stiffness, and orthogonality of the two in dilute single-network gels.

a) End-linked PEG networks of varying cross-link density, including TetraPEG (A4 + B4) other A2 + B4 networks (like this work) and other mechanophore networks (Wang et al.19). TCB gels are marked by stars. b) Pendant-linked single-network gels of varied chemistry and topology, including polysaccharide, poly(vinyl alcohol) (PVA), polyacrylamide (PAam), and slide-ring gels, compared to this work. Details for shown data can be found in Supplementary Table 6. Gels in (a) and (b) are \(88\pm 4 \%\) solvent by weight, are made up of only a single network, and do not involve multistep fabrication or fillers. We note that highly entangled PAam gels11 do fit these criteria and achieve high stiffness and toughness; these materials have been omitted simply to improve readability of the other data. Highly entangled PAam gels within this concentration range can achieve tearing energies between 73 J/m2 and 1.5 kJ/m2, alongside Young’s moduli of 190 kPa to 100 kPa, respectively, depending on water content during gelation. c) Tearing energy vs. modulus for several material families normalized by the tearing energy and modulus of the toughest sample of each dataset, illustrating differing correlations between these properties.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information Materials and Methods

Supplementary Text, Figs. 1–14, Tables 1–8 and References.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Herzog-Arbeitman, A., Kevlishvili, I., Sen, D. et al. Tetrafunctional cyclobutanes tune toughness via network strand continuity. Nat. Chem. 18, 309–316 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41557-025-01984-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41557-025-01984-9

This article is cited by

-

Cycloreversion-enhanced toughness and degradability in mechanophore-embedded end-linked polymer networks

Nature Communications (2026)