Abstract

Diamond’s elementary chiral constituent—skew-tetramantane—features extreme rigidity, stability and a precisely defined geometry, epitomizing the parent structure of a σ-helicene. While skew-tetramantane is naturally occurring in trace fractions in fossil fuels, efforts over several decades towards its selective synthesis remained unfruitful. With the recent advances in photocatalysis and transition metal catalysis to tame radical and carbene species, we have now devised a targeted total synthesis of skew-tetramantane by means of a stereoselective adamantalogous cage extension. A first cap attachment was effected by a photocatalytic Giese reaction, while remarkable regio-, diastereo- and enantiocontrol were achieved by an intramolecular C(sp3)−H insertion using Davies’ chiral rhodium catalysts. After a Buchner–Curtius–Schlotterbeck ring expansion and a stereoselective Mukaiyama hydration, the fusion to the adamantine skew-tetramantane structure was completed by an intramolecular C(sp3)−H insertion of a non-stabilized carbenoid. Here we show that this approach provides access to synthetic skew-tetramantane in isomerically pure form with σ-helicity defined by the catalyst, marking a selective pathway to higher diamondoids.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

For two-dimensional (2D) carbon frameworks, a remarkably rich diversity of synthetically accessible benzenoid structures superimposable on graphene’s honeycomb surface serves as a cornerstone for the molecular sciences, while chirality in condensed polyaromatics results from the three-dimensional (3D) winding of ortho-fused π-helicenes1,2 (Fig. 1a). Diamond on the other hand—as the most iconic form of 3D carbon—stands out, not only for its captivating structure, but also its exceptional inertness and hardness, as well as unique optical, thermal and electronic characteristics, along with excellent biocompatibility3,4. However, neither natural nor synthetic diamonds are accessible with atomic precision5,6. By contrast, diamondoids, as hydrogen-terminated fragments of the diamond lattice, are distinguishable as structurally defined molecules (Fig. 1b) and exhibit spectral and electronic behaviour related to bulk diamond, with physicochemical properties depending on size, shape and symmetry. Discrete diamondoids are therefore highly sought after compounds for optics, electronics, quantum computing, diamond synthesis or pharmaceuticals as homologues of adamantane drugs7,8,9,10,11,12,13. Besides controlling size, methods to access isomerically pure diamondoids, as well as functionalized derivatives, are therefore essential for their broad implementation14. Intriguingly, diamondoids are natural products that are found in trace fractions in raw petroleum and deep natural gas condensates and can be obtained after multiple sophisticated separations15,16,17. Synthetically, only the three lower diamondoids are accessible by Schleyer’s stabilomeric carbocation method18,19,20,21,22,23,24. This process is thought to proceed through an astonishing 3 × 104 intermediates to triamantane25,26,27. However, due to the intangible number of possible cationic intermediates and local minima traps on the potential energy surface, the synthesis of tetramantane or other higher diamondoids failed by this strategy28. Furthermore, as thermodynamically controlled processes favour the most stable isomer, the synthesis of a majority of higher diamondoids is stymied by the differences in ground-state energy, which are predicted for the first isomers to increase from iso- to anti- to skew-tetramantane29. Analogous to McKervey’s seminal gas-phase reforming reaction for anti-tetramantane, mimics of harsh petrochemical processes, such as free-radical cracking, deliver highly complex mixtures akin to natural diamondoids in fossil fuels30,31. Enantiopure skew-tetramantane, representing the σ-helical nucleus of diamond, was thus obtained exclusively from fossil fuels and isolated through multiple elaborate high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) purifications on limited scale32. A mild low-temperature approach operating under kinetic control, ideally with reactivity and selectivity regulated by refined catalytic means, is therefore a prerequisite for the synthetic addressability of higher diamondoids. As it appeared that the prospects for overcoming the hurdles of a controlled higher diamondoid synthesis have improved decisively by the evolution of visible-light photocatalysis and precise C–H insertion chemistry with well-defined rhodium carbenes, we embarked on exploring the feasibility of a mild stereoselective preparation of diamond’s chiral core—skew-tetramantane.

a, C(sp2). Benzenoids as parts of the 2D honeycomb structure of graphene; 3D topology of π-helicenes. b, C(sp3). Diamondoids with face-fused cages superimposable on the 3D diamond lattice. c, Isomerism, symmetry and σ-helicity of tetramantanes. d, Synthetic strategy. Adamantalogous cage extension for the total synthesis of skew-tetramantane, diamond’s chiral core.

Synthetic strategy

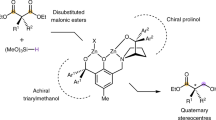

At the heart of a stereoselective synthesis of skew-tetramantane is the assembly of a uniquely rigid and compact component of the diamond lattice with accurate control over configuration. Seeking a systematic approach, we evaluated an adamantalogous cage extension as a homologation strategy by forming three carbon–carbon bonds to mount a four-carbon cap to a hexagonal face of triamantane. A random cage fusion to one of the eight faces of C2v-symmetric triamantane would therefore give rise to all four tetramantane isomers, (P)- and (M)-skew-, anti- and iso-tetramantane (Fig. 1c). For the specific formation of skew-tetramantane, we therefore considered 2-bromotriamantane for a photocatalytic radical anchoring to attach a guiding handle at the medial position (Fig. 1d). The anticipated stereoselectivity is subsequently determined within a desymmetrization during the formation of the second C–C bond by a transition metal-catalysed C(sp3)–H insertion. Notably, it was thus expected that the numerous C–H bonds with a similar chemical environment render regio-, diastereo- and enantiocontrol a formidable challenge. Once the second C–C bond is formed, the structure is pronouncedly rigidified, severely reducing the conformational freedom to forge the third bond. Furthermore, to enable the formation of the final bond of the cage, the configuration of the cap’s stereogenic centre must be accurately predefined before closure. Due to the limited dynamics and unilateral accessibility, an insertion of a non-stabilized carbenoid was therefore envisaged for completing the rigid diamondoid structure, which would ultimately provide access to synthetic skew-tetramantane with defined σ-helicity.

Anchoring and cyclization

We started our synthetic work with 2-bromotriamantane (1) obtained by Schreiner’s medial bromination of triamantane, which was first prepared from norbornadiene24,33. To anchor the handle as element of the cap for its fusion to form a cage, a visible light-driven photocatalytic Giese reaction34 was employed to expeditiously deliver product 2 (60%, Fig. 2). C1 homologation to incorporate the cap’s third carbon was followed by condensation with TsNHNH2, providing tosylhydrazone 3, which was converted to diazoester 4 (45% yield for 7 steps). However, when attempting to override the inherent preference for tertiary (3°) over secondary (2°) C–H bond insertion with various different catalysts (Supplementary Table 1), the exclusive formation of the quaternary (4°) product (±)-5 impaired this exploratory approach35,36. To suppress reactions at the 3° C–H bonds, the handle in substrate 6 was therefore shortened to favour the desired 2° C–H bond insertion by forming the five-membered ring product 7 over otherwise strained ring systems. Nonetheless, a remaining challenge was faced by the four accessible 2° C–H bonds together with the generation of an additional stereogenic centre, giving rise to eight potential products attainable in this cyclization. Considering the remarkable selectivities achieved with Davies’ rhodium catalysts even in the most difficult scenarios37, we anticipated that differentiating the four 2° C–H positions would be feasible with regio-, diastereo- and enantioselectivity if controlled by this versatile catalysis platform. Thereafter, we envisioned that the diamondoid’s six-membered ring structure could be accessible upon ring expansion, introducing the fourth carbon of the cap required to complete the cage. Correspondingly, an analogous photocatalytic Giese reaction of 2-bromotriamantane was evaluated, delivering product (±)-8 in 71% yield (Fig. 3), whereas subsequent oxidation to ketone (±)-9 and deacetylative Regitz diazo transfer gave the respective diazoester substrate 6 by a stereoconvergent process in 87% yield (for two steps). Gratifyingly, with substrate 6 in hand, we observed that Rh2(OAc)4 provides the C–H bond insertion product (±)-7a′/ent-7a′ with excellent diastereoselectivity, whereas no corresponding cyclization was detected with copper or silver catalysts. To our delight, an initial 72:28 enantiomeric ratio (e.r.) was observed with the chiral Rh2(R- DOSP)4 catalyst37 and, after optimization, an exceptionally high yielding diastereo- and enantioselective carbene insertion governed by the sterically demanding Rh2(R-TCPTAD)4 catalyst culminated in 7a′ with an extraordinary 98:2 e.r., 97% yield and a diastereomeric ration (d.r.) of >20:1. Notably, the highly regio- and stereocontrolled reaction favours the formation of the five-membered insertion product, the precursor for the ring expansion to create the diamondoid structure of skew-tetramantane.

As an alternative to overcoming the inherent preference for 3° C–H bond insertion, a shorter handle is installed to favour reactions at 2° C–H bonds, leading to a five-membered insertion product for a subsequent ring expansion. [Ir], (Ir[dF(CF3)ppy]2(dtbpy))PF6; Xantphos, 4,5-bis(diphenylphosphino)-9,9-dimethylxanthene; DMP, Dess–Martin periodinane; Bn, benzyl.

a, Installation of the shorter handle and synthesis of the diazoester substrate. b, Optimization of the stereoselective C(sp3)–H insertion to differentiate the eight possible cyclization products. PCC, pyridinium chlorochromate; p-ABSA, p -acetamido-benzenesulfonyl azide; DBU, diaza-bicycloundecene; ND, no detection of 7.

Ring expansion

We next examined the Buchner–Curtius–Schlotterbeck reaction to conduct the ring expansion38 (Fig. 4). To prepare the substrate for the rearrangement, hydrogenolysis to the carboxylic acid was combined with an aerobic photodecarboxylative oxidation for which the Nicewicz acridinium catalyst was discovered to be optimal39, giving ketone 10 in 89% yield for two steps (Supplementary Table 2). The rearrangement with ethyl diazoacetate and BF3 etherate proceeded with a high migratory selectivity of 5:1 (Supplementary Table 3) in favour of the desired product 11, as confirmed by X-ray crystallography. Subsequent triflation and palladium-catalysed reduction40 delivered the key α,β-unsaturated ester intermediate 12.

Ring expansion and the de novo formation of the diamondoid cage. [Nicewicz acridinium] catalyst, 9-mesityl-3,6-di-tert-butyl-10-phenylacridinium BF4; DIPEA, N,N-diisopropylethylamine; dppf, 1,1′-bis(diphenylphosphino)ferrocene; dpm, dipivaloylmethanato; TEMPO, 2,2,6,6-tetramethylpiperidinyloxyl; ND, not detected; brsm, based on recovered starting materials; TTMSS, tris(trimethyl-silyl)silane.

Cage completion

To forge the last C–C bond of the cage, the fourth carbon of the cap was prepositioned towards the remaining C–H bond for the adamantalogous cage extension by controlling the configuration in a highly diastereoselective hydrogenation (13, d.r. >95:5). After aldehyde synthesis to generate intermediate 14, both the absolute and the relative configuration were confirmed by X-ray crystallography. To complete the synthesis, an intramolecular insertion of a carbene was anticipated to directly afford (P)-skew-tetramantane (20). However, upon converting 14 into the hydrazone followed by in situ generation of the non-stabilized alkyl diazo substrate41, no C–H insertion product was observed with Rh2(OAc)4 and the β-H shift alkene product 15 was obtained exclusively42. To circumvent this reactivity, a methoxy group was introduced from the α,β-unsaturated ester 12 by a Mukaiyama hydration43, providing 16 with a d.r. >95:5 for the required configuration, followed by methylation and aldehyde synthesis to afford precursor 17. To our delight, after hydrazone formation, the in situ-formed diazo substrate effectively converted into the desired insertion product 18 in 47% yield (90% based on recovered starting materials) with the structure confirmed by X-ray crystallography. The methoxy group of 18 was substituted to form bromide 19 (97% yield), which represents a valuable linchpin compound for diamondoid derivatives. Following a highly efficient photodehalogenation44, (P)-skew-tetramantane (20) was obtained in 99% yield and its full consistency with natural skew-tetramantane isolated from fossil fuels32,45,46 was confirmed by nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy (1.2 GHz). The overall diamondoid homologation from triamantane to skew-tetramantane was thus enabled by a combination of visible-light photocatalysis to modulate radical chemistry and highly selective C–H insertion reactions, ultimately allowing the controlled synthesis of a higher diamondoid.

Conclusion

The feasibility of an adamantalogous cage extension to systematically access higher diamondoids was established by the selective synthesis of (P)-skew-tetramantane. While the availability of natural higher diamondoids in defined form is limited, it is anticipated that the immense diversity of diamond constituents will become accessible by the transformative advances in synthetic methodology. In particular photocatalysis and transition metal catalysis for controlled reactions through radical and carbene species bear potential to synthetically access different structurally well-defined diamondoid frameworks. Similar to the numerous versatile methods to form 2D polyaromatics, we expect that the selective synthesis of diamondoids will provide a wide variety of 3D architectures with distinct physical features, stability, rigidity and precisely defined exit vectors for their broad implementation in pharmaceuticals, biomarkers, seeds for diamond synthesis or for their application in material science, optics or electronics.

Methods

Stereoselective intramolecular carbene insertion

To a vial under argon was added Rh2(R-TCPTAD)4 (72.8 mg, 34.5 µmol, 1.00 mol%) and CH2Cl2 (60 ml). At −80 °C under stirring, a solution of substrate 6 (1.48 g, 3.45 mmol, 1.00 equiv.) in CH2Cl2 (45 ml) was added dropwise over 5 min and the progress of the reaction was monitored by thin layer chromatography. After 16 hours of stirring at −80 °C, the mixture was concentrated in vacuo and the residue purified by column chromatography on silica gel to afford the product 7a′ as a colourless oil (1.29 g, 3.21 mmol, 93%, 98:2 e.r., >20:1 d.r.). The d.r. was determined by 1H NMR before column chromatography and the e.r. by HPLC on a chiral stationary phase with the purified product. Please refer to the Supplementary Information for further experimental procedures and details.

Data availability

The data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper, its Supplementary Information and via Zenodo at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17237986 (ref. 47). Supplementary crystallographic data for this paper can be obtained from the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre at CCDC2419727 ((±)-5), CCDC2409136 (7c), CCDC2409137 (11), CCDC2413110 (14) and CCDC2409138 (18).

References

Narita, A., Wang, X.-Y., Feng, X. & Müllen, K. New advances in nanographene chemistry. Chem. Soc. Rev. 44, 6616–6643 (2015).

Crassous, J., Stará, I. G. & Starý, I. (eds) Helicenes: Synthesis, Properties and Applications (Wiley-VCH, 2022).

Bragg, W. H. & Bragg, W. L. The structure of the diamond. Nature 91, 557 (1913).

Field, J. E. (ed) Properties of Natural and Synthetic Diamond (Academic, 1992).

Williams, O. A. (ed) Nanodiamond (Royal Society of Chemistry, 2014).

Jing, J. et al. Scalable production of ultraflat and ultraflexible diamond membrane. Nature 636, 627–634 (2024).

Fokin, A. A., Šekutor, M. & Schreiner, P. R. The Chemistry of Diamondoids: Building Blocks for Ligands, Catalysts, Pharmaceuticals, and Materials (Wiley-VCH, 2024).

Balaban, A. T. & Schleyer, P.vR. Systematic classification and nomenclature of diamond hydrocarbons—I: Graph-theoretical enumeration of polymantanes. Tetrahedron 34, 3599–3609 (1978).

Stauss, S. & Terashima, K. Diamondoids: Synthesis, Properties, and Applications (Pan Stanford Publishing, 2017).

Schwertfeger, H., Fokin, A. A. & Schreiner, P. R. Diamonds are a chemist’s best friend: diamondoid chemistry beyond adamantane. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 47, 1022–1036 (2008).

Landt, L. et al. Optical response of diamond nanocrystals as a function of particle size, shape, and symmetry. Phys. Rev. Lett. 103, 047402 (2009).

Clay, W. A., Dahl, J. E. P., Carlson, R. M. K., Melosh, N. A. & Shen, Z.-X. Physical properties of materials derived from diamondoid molecules. Rep. Prog. Phys. 78, 016501 (2015).

Yang, W. L. et al. Monochromatic electron photoemission from diamondoid monolayers. Science 316, 1460–1462 (2007).

Gunawan, M. A. et al. Diamondoids: functionalization and subsequent applications of perfectly defined molecular cage hydrocarbons. New J. Chem. 38, 28–41 (2014).

Lin, R. & Wilk, Z. A. Natural occurrence of tetramantane (C22H28), pentamantane (C26H32) and hexamantane (C30H36) in a deep petroleum reservoir. Fuel 74, 1512–1521 (1995).

Dahl, J. E. et al. Diamondoid hydrocarbons as indicators of natural oil cracking. Nature 399, 54–57 (1999).

Dahl, J. E., Liu, S. G. & Carlson, R. M. K. Isolation and structure of higher diamondoids, nanometer-sized diamond molecules. Science 299, 96–99 (2003).

Prelog, V. & Seiwerth, R. Über die Synthese des Adamantans. Chem. Ber. 74, 1644–1648 (1941).

Schleyer, P.vR. A simple preparation of adamantane. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 79, 3292–3292 (1957).

Cupas, C., Schleyer, P.vR. & Trecker, D. J. Congressane. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 87, 917–918 (1965).

Fǎrcaşiu, D., Bohm, H. & Schleyer, P.vR. Stepwise elaboration of diamondoid hydrocarbons. Synthesis of diamantane from adamantane. J. Org. Chem. 42, 96–102 (1977).

Williams, V. Z., Schleyer, P.vR., Gleicher, G. J. & Rodewald, L. B. Triamantane. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 88, 3862–3863 (1966).

Engler, E. M., Farcasiu, M., Sevin, A., Cense, J. M. & Schleyer, P.vR. Mechanism of adamantane rearrangements. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 95, 5769–5771 (1973).

Hollowood, F. S., McKervey, M. A., Hamilton, R. & Rooney, J. J. Synthesis of triamantane. J. Org. Chem. 45, 4954–4958 (1980).

Gund, T. M., Schleyer, P.vR., Gund, P. H. & Wipke, W. T. Computer assisted graph theoretical analysis of complex mechanistic problems in polycyclic hydrocarbons. Mechanism of diamantane formation from various pentacyclotetradecanes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 97, 743–751 (1975).

Tanaka, N., Kan, T. & Iizuka, T. A. Reasonable triamantane rearrangement path searched by the selective disource propagation algorithm. J. Chem. Inf. Comput. Sci. 23, 177–182 (1983).

McKervey, M. A. Adamantane rearrangements. Chem. Soc. Rev. 3, 479–512 (1974).

Schleyer, P.vR., Osawa, E. & Drew, M. G. B. Nonacyclo[11.7.1.12,18.03,16.04,13.05,10.06,14.07,11.015,20]docosane, a bastard tetramantane. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 90, 5034–5036 (1968).

McKervey, M. A. Synthetic approaches to large diamondoid hydrocarbons. Tetrahedron 36, 971–992 (1980).

Burns, W., McKervey, M. A., Mitchell, T. R. B. & Rooney, J. J. A new approach to the construction of diamondoid hydrocarbons. Synthesis of anti-tetramantane. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 100, 906–911 (1978).

Dahl, J. E. P. et al. Synthesis of higher diamondoids and implications for their formation in petroleum. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 49, 9881–9885 (2010).

Schreiner, P. R. et al. [123]Tetramantane: parent of a new family of σ-helicenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131, 11292–11293 (2009).

Schreiner, P. R. et al. Functionalized nanodiamonds: triamantane and [121]tetramantane. J. Org. Chem. 71, 6709–6720 (2006).

Escobar, R. A. & Johannes, J. W. Reductive radical conjugate addition of alkyl electrophiles catalyzed by a cobalt/iridium photoredox system. Org. Lett. 23, 6046–6051 (2021).

Davies, H. M. L., Hansen, T. & Churchill, M. R. Catalytic asymmetric C−H activation of alkanes and tetrahydrofuran. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 122, 3063–3070 (2000).

Lombard, F. J. & Coster, M. J. Catalytic rhodium(II)-catalysed intramolecular C–H insertion α- to oxygen: reactivity, selectivity and applications to natural product synthesis. Org. Biomol. Chem. 13, 6419–6431 (2005).

Davies, H. M. L. & Liao, K. Dirhodium tetracarboxylates as catalysts for selective intermolecular C–H functionalization. Nat. Rev. Chem. 3, 347–360 (2019).

Candeias, N. R., Paterna, R. & Gois, P. P. Homologation reaction of ketones with diazo compounds. Chem. Rev. 116, 2937–2981 (2016).

Joshi-Pangu, A. et al. Acridinium-based photocatalysts: a sustainable option in photoredox catalysis. J. Org. Chem. 81, 7244–7249 (2016).

Scheerer, J. R., Lawrence, J. F., Wang, G. C. & Evans, D. A. Asymmetric synthesis of salvinorin A, a potent κ-opioid receptor agonist. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 129, 8968–8969 (2007).

Fulton, J. R., Aggarwal, V. K. & de Vicente, J. The use of tosylhydrazone salts as a safe alternative for handling diazo compounds and their applications in organic synthesis. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2005, 1479–1492 (2005).

Xiao, F. & Wang, J. 1,2-Migration in rhodium(II) carbene transfer reaction: remarkable steric effect on migratory aptitude. J. Org. Chem. 71, 5789–5791 (2006).

Crossley, S. W. M., Obradors, C., Martinez, R. M. & Shenvi, R. A. Mn, Fe, and Co-catalyzed radical hydrofunctionalizations of olefins. Chem. Rev. 116, 8912–9000 (2016).

Devery, J. J., Nguyen, J. D., Dai, C. & Stephenson, C. R. J. Light-mediated reductive debromination of unactivated alkyl and aryl bromides. ACS Catal. 6, 5962–5967 (2016).

Ebeling, D. et al. Assigning the absolute configuration of single aliphatic molecules by visual inspection. Nat. Commun. 9, 2420 (2018).

Balaban, A. T. et al. NMR spectral properties of the tetramantanes–nanometer-sized diamondoids. Magn. Reson. Chem. 53, 1003–1018 (2015).

Li, X.-Y. & Sparr, C. Stereoselective total synthesis of skew-tetramantane [Dataset]. Zenodo https://zenodo.org/records/17237987 (2025).

Acknowledgements

This project has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (grant agreement no. 101002471) and from the Swiss National Science Foundation (10001653). We thank D. Häussinger for NMR support and A. Prescimone for X-ray crystallography.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.S. and X.-Y.L. conceived the study, designed the experiments and analysed the data. X.-Y.L. performed the experiments. C.S. and X.-Y.L. wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

A patent application has been filed for all aspects of this work. Applicant: University of Basel. Inventors: C.S. and X.-Y.L. Application number: EP25185320.6. Status: submitted.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Chemistry thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figs. 1–8, Tables 1–6, Methods, Computational studies, NMR spectra, HPLC data, X-ray data and References.

Supplementary Data 1

This file contains the Cartesian coordinates for all optimized geometries.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, XY., Sparr, C. Stereoselective total synthesis of skew-tetramantane. Nat. Chem. (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41557-025-02026-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41557-025-02026-0