Abstract

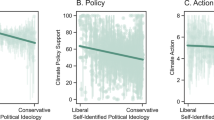

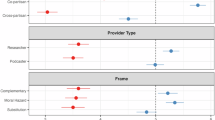

Partisanship is one of the largest and most studied social barriers to climate change mitigation in the United States. Here we expand conceptualizations of ‘left-right’ or ‘Democrat-Republican’ towards understanding partisanship as a multidimensional social identity with both negative and positive elements. Partisan support or opposition for climate action can be driven by identification with the partisan in-group (positive or ‘expressive’ partisanship), as well as perceived threats from the ‘out-group’ (negative partisanship). Using original survey data, we show that when negative and expressive partisanship is low, climate policy support is similar for Republicans and Democrats. However, differences in policy support increase when partisan identification amplifies. Yet, for climate behaviours, we find more limited partisan effects. The proposed multidimensional partisanship framework revisits the role of partisan polarization in shaping climate change action and points to alternative ways to transcend partisan barriers.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$32.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $21.58 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

Full original survey data are available on the Harvard Dataverse63 with the identifier https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/8V9FDH.

Code availability

Analytical replication materials are available on the Harvard Dataverse63 with the identifier https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/8V9FDH.

References

Cook, J. et al. Consensus on consensus: a synthesis of consensus estimates on human-caused global warming. Environ. Res. Lett. 11, 048002 (2016).

Steffen, W. et al. Trajectories of the earth system in the anthropocene. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 115, 8252–8259 (2018).

Unruh, G. C. Escaping carbon lock-in. Energy Policy 30, 317–325 (2002).

Sovacool, B. K., Hess, D. J. & Cantoni, R. Energy transitions from the cradle to the grave: a meta-theoretical framework integrating responsible innovation, social practices, and energy justice. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 75, 102027 (2021).

Compston, H. & Bailey, I. Climate policy strength compared: China, the US, the EU, India, Russia, and Japan. Climate Policy 16, 145–164 (2016).

Farrell, J. Corporate funding and ideological polarization about climate change. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 113, 92–97 (2016).

Oreskes, N. & Conway, E. M. Merchants of Doubt: How a Handful of Scientists Obscured the Truth on Issues from Tobacco Smoke to Global Warming (Bloomsbury Publishing, 2011).

Hornsey, M. J., Harris, E. A., Bain, P. G. & Fielding, K. S. Meta-analyses of the determinants and outcomes of belief in climate change. Nat. Clim. Change 6, 622–626 (2016).

McCright, A. M., Marquart-Pyatt, S. T., Shwom, R. L., Brechin, S. R. & Allen, S. Ideology, capitalism, and climate: explaining public views about climate change in the United States. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 21, 180–189 (2016).

Kollmuss, A. & Agyeman, J. Mind the gap: why do people act environmentally and what are the barriers to pro-environmental behavior? Environ. Educ. Res. 8, 239–260 (2002).

Allen, S., Dietz, T. & McCright, A. M. Measuring household energy efficiency behaviors with attention to behavioral plasticity in the United States. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 10, 133–140 (2015).

O’Connor, R. E., Bord, R. J., Yarnal, B. & Wiefek, N. Who wants to reduce greenhouse gas emissions? Soc. Sci. Q. 83, 1–17 (2002).

Mildenberger, M., Howe, P. D. & Miljanich, C. Households with solar installations are ideologically diverse and more politically active than their neighbours. Nat. Energy 4, 1033–1039 (2019).

Sintov, N. D., Abou-Ghalioum, V. & White, L. V. The partisan politics of low-carbon transport: why Democrats are more likely to adopt electric vehicles than Republicans in the United States. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 68, 101576 (2020).

Greene, S. Social identity theory and party identification. Soc. Sci. Q. 85, 136–153 (2004).

Iyengar, S., Sood, G. & Lelkes, Y. Affect, not ideology: a social identity perspective on polarization. Public Opin. Q. 76, 405–431 (2012).

Lyons, J. The family and partisan socialization in red and blue america. Polit. Psychol. 38, 297–312 (2017).

Sapiro, V. Not your parents’ political socialization: introduction for a new generation. Annu. Rev. Polit. Sci. 7, 1–23 (2004).

Bisgaard, M. & Slothuus, R. Partisan elites as culprits? how party cues shape partisan perceptual gaps. Am. J. Polit. Sci. 62, 456–469 (2018).

Carmichael, J. T. & Brulle, R. J. Elite cues, media coverage, and public concern: an integrated path analysis of public opinion on climate change, 2001–2013. Environ. Polit. 26, 232–252 (2017).

Cohen, G. L. Party over policy: the dominating impact of group influence on political beliefs. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 85, 808 (2003).

Mayer, A. National energy transition, local partisanship? Elite cues, community identity, and support for clean power in the United States’. Energy Res. Soc.Sci. 50, 143–150 (2019).

Tajfel, H. & Turner, J. C. in The Social Psychology of Intergroup Relations (eds Austin, W. G. & Worchel, S.) 33–47 (Brooks/Cole, 1979).

Bankert, A. Negative and positive partisanship in the 2016 US presidential elections. Polit. Behav. 43, 1467–1485 (2021).

Green, D., Palmquist, B. & Schickler, E. Partisan Hearts and Minds: Political Parties and the Social Identities of Voters. (Yale Univ. Press, 2002).

Huddy, L., Mason, L. & Aarøe, L. Expressive partisanship: campaign involvement, political emotion, and partisan identity. Am. Pol. Sci. Rev. 109, 1–17 (2015).

Huddy, L., Bankert, A. & Davies, C. Expressive versus instrumental partisanship in multiparty European systems. Polit. Psychol. 39, 173–199 (2018).

Zhong, Chen-Bo, Dijksterhuis, A. & Galinsky, A. D. The merits of unconscious thought in creativity. Psychol. Sci. 19, 912–918 (2008).

Bankert, A. in Research Handbook on Political Partisanship (eds Oscarsson, H. & Holmberg, S.) 89–101 (Edward Elgar Publishing, 2020).

Brewer, M. B. The psychology of prejudice: ingroup love and outgroup hate? J. Soc. Issues 55, 429–444 (1999).

Abramowitz, A. I. & Webster, S. The rise of negative partisanship and the nationalization of US elections in the 21st century. Elect. Stud. 41, 12–22 (2016).

Abramowitz, A. I. & Webster, S. W. Negative partisanship: why Americans dislike parties but behave like rabid partisans. Polit. Psychol. 39, 119–135 (2018).

Lee, A. H., Lelkes, Y., Hawkins, C. B. & Theodoridis, A. G. Negative partisanship is not more prevalent than positive partisanship. Nat. Hum. Behav. 6, 951–963 (2022).

Endres, K. & Panagopoulos, C. Boycotts, buycotts, and political consumerism in America. Res. Polit. https://doi.org/10.1177/2053168017738632 (2017).

Webster, S. W. & Abramowitz, A. I. The ideological foundations of affective polarization in the US electorate. Am. Polit. Res. 45, 621–647 (2017).

Brennan, G. & Hamlin, A. Expressive voting and electoral equilibrium. Public Choice 95, 149–175 (1998).

Mayer, A. Support for displaced coal workers is popular and bipartisan in the United States: evidence from western Colorado. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 90, 102593 (2022).

Hazboun, S. O. The politics of decarbonization: examining conservative partisanship and differential support for climate change science and renewable energy in Utah. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 70, 101769 (2020).

Stadelmann-Steffen, I. & Dermont, C. The unpopularity of incentive-based instruments: what improves the cost–benefit ratio? Public Choice 175, 37–62 (2018).

Tobler, C., Visschers, V. H. M. & Siegrist, M. Addressing climate change: determinants of consumers’ willingness to act and to support policy measures. J. Environ. Psychol. 32, 197–207 (2012).

Mize, T. D. Best practices for estimating, interpreting, and presenting nonlinear interaction effects. Sociol. Sci. 6, 81–117 (2019).

Williams, R. Using the margins command to estimate and interpret adjusted predictions and marginal effects. Stata J. 12, 308–331 (2012).

Gustafson, A. The development of partisan polarization over the green new deal. Nat. Clim. Change 9, 940–944 (2019).

Jenkins-Smith, H. C. Partisan asymmetry in temporal stability of climate change beliefs. Nat. Clim. Change 10, 322–328 (2020).

Goldberg, M. H. Shifting Republican views on climate change through targeted advertising. Nat. Clim. Change 11, 573–577 (2021).

Valkengoed, A. M. & Steg, L. Meta-analyses of factors motivating climate change adaptation behaviour. Nat. Clim. Change 9, 158–163 (2019).

Steg, L. Limiting climate change requires research on climate action. Nat. Clim. Change 8, 759–761 (2018).

Otto, I. M. et al. Social tipping dynamics for stabilizing Earth’s climate by 2050. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 117, 2354–2365 (2020).

Winkelmann, R. Social tipping processes towards climate action: a conceptual framework’. Ecol. Econ. 192, 107242 (2022).

McCright, A. M. & Dunlap, R. E. Anti-reflexivity. Theory Cult. Soc. 27, 100–133 (2010).

Campbell, T. H. & Kay, A. C. Solution aversion: on the relation between ideology and motivated disbelief. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 107, 809 (2014).

Hamilton, L. C. Education, politics and opinions about climate change evidence for interaction effects. Climatic Change 104, 231–242 (2011).

Ballew, M. T., Pearson, A. R., Goldberg, M. H., Rosenthal, S. A. & Leiserowitz, A. Does socioeconomic status moderate the political divide on climate change? The roles of education, income, and individualism. Glob. Environ. Change 60, 102024 (2020).

Smith, E. K. & Hempel, L. M. Alignment of values and political orientations amplifies climate change attitudes and behaviors. Climatic Change 172, 1–28 (2022).

McCright, A. M. & Dunlap, R. E. Defeating Kyoto: the conservative movement’s impact on US climate change policy. Soc. Probl. 50, 348–373 (2003).

Roulin, N. Don’t throw the baby out with the bathwater: comparing data quality of crowdsourcing, online panels, and student samples. Ind. Organ. Psychol. 8, 190–196 (2015).

Walter, S. L. A tale of two sample sources: do results from online panel data and conventional data converge? J. Bus. Psychol. 34, 425–452 (2019).

European Social Survey. European Social Survey Round 8 Data: Edition 2.0. (Norwegian Centre for Research Data, 2016).

Diekmann, A. & Preisendörfer, P. Green and greenback: the behavioral effects of environmental attitudes in low-cost and high-cost situations. Ration. Soc. 15, 441–472 (2003).

Pew Research Center. Partisanship and Political Animosity in 2016 (Pew Research Center, 2016).

Smith, E. K. & Mayer, A. A social trap for the climate? Collective action, trust and climate change risk perception in 35 countries. Glob. Environ. Change 49, 140–153 (2018).

Mood, C. Logistic regression: why we cannot do what we think we can do, and what we can do about it. Eur. Sociol. Rev. 26, 67–82 (2010).

Smith, E. K. & Mayer, A. Replication Data for: Multi-dimensional Partisanship Shapes Climate Policy Support and Behaviors (Harvard Dataverse, 2022); https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/8V9FDH

Acknowledgements

We thank J. Bognar for insightful feedback and suggestions, and the Leibniz Association (project DOMINOES, E.K.S.) for the support provided by allowing the survey data collection. This work is further supported by the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF) within the framework of the National Research Programme ‘Sustainable Economy: resource-friendly, future-oriented, innovative’ (NRP 73 Grant: 407340−172363, E.K.S.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.P.M and E.K.S. designed the research, developed and analysed the results, and co-wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Climate Change thanks Clive Bean, Alexa Spence and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figs. 1–3 and Tables 1–14.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Mayer, A.P., Smith, E.K. Multidimensional partisanship shapes climate policy support and behaviours. Nat. Clim. Chang. 13, 32–39 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-022-01548-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-022-01548-6

This article is cited by

-

Tracking business opportunities for climate solutions using AI in regulated accounting reports

Nature Communications (2025)

-

Socio-demographic disparities in the familiarity with coastal climate adaptation strategies: implications for coastal management and climate justice

Natural Hazards (2025)

-

Environmental actions, support for policy, and information’s provision: experimental evidence from the US

Climatic Change (2025)

-

The times they are changing? Support for green policy measures in Germany in times of uncertainty

Zeitschrift für Politikwissenschaft (2025)

-

Opinion Dynamic and Social Clustering in a 2D Space: An Agent Based Experiment

Computational Economics (2025)