Abstract

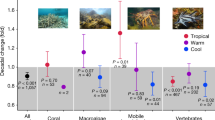

Warming seas are expected to drive marine life poleward. However, few systematic observations confirm movement among entire communities at both warm and cool range edges. We analysed two continent-scale reef monitoring datasets to quantify changes in latitudinal range edges of 662 Australian shallow-water reef fishes and invertebrates over a decade punctuated by climate extremes. Temperate and tropical species both showed little net movement overall, with retreat often balancing expansion across the continent. Within regions, however, range edges shifted ~100 km per decade, on average, in the poleward or equatorward directions expected from warming or cooling. Although some species responded rapidly to temperature change, we found little evidence for mass poleward migration over the decade. Previous studies based on extreme species observations, rather than tracking all species through time, may have overestimated the prevalence, magnitude and longevity of range shifts amongst marine taxa.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$32.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $21.58 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

All original survey data can be directly accessed and downloaded through the RLS website and portal: https://reeflifesurvey.com/survey-data/. SST data from the NOAA Coral Reef Watch programme are freely available at https://coralreefwatch.noaa.gov/main/. The GitHub repository can be found at https://github.com/yannherfux/range_shifts (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.12817835)68. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

Data subsets and R scripts specifically used for this analysis are available via GitHub at https://github.com/yannherfux/range_shifts (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.12817835)68.

References

Cheung, W. W. L. et al. Projecting global marine biodiversity impacts under climate change scenarios. Fish Fish. 10, 235–251 (2009).

Burrows, M. T. et al. Geographical limits to species-range shifts are suggested by climate velocity. Nature 507, 492–495 (2014).

García Molinos, J. et al. Climate velocity and the future global redistribution of marine biodiversity. Nat. Clim. Change 6, 83–88 (2015).

Hodapp, D. et al. Climate change disrupts core habitats of marine species. Glob. Change Biol. 29, 3304–3317 (2023).

Beas-Luna, R. et al. Geographic variation in responses of kelp forest communities of the California current to recent climatic changes. Glob. Change Biol. 26, 6457–6473 (2020).

Cheung, W. W. L. et al. Climate-change induced tropicalisation of marine communities in Western Australia. Mar. Freshw. Res. 63, 415–427 (2012).

McLean, M. et al. Disentangling tropicalization and deborealization in marine ecosystems under climate change. Curr. Biol. 31, 4817–4823 (2021).

Verges, A. et al. The tropicalization of temperate marine ecosystems: climate-mediated changes in herbivory and community phase shifts. Proc. Biol. Sci. 281, 20140846 (2014).

Dahms, C. & Killen, S. S. Temperature change effects on marine fish range shifts: a meta-analysis of ecological and methodological predictors. Glob. Change Biol. 29, 4459–4479 (2023).

Kotiaho, J. S. & Tomkins, J. L. Meta‐analysis, can it ever fail? Oikos 96, 551–553 (2002).

Fredston-Hermann, A. et al. Cold range edges of marine fishes track climate change better than warm edges. Glob. Change Biol. 26, 2908–2922 (2020).

Tanaka, K. R. et al. North Pacific warming shifts the juvenile range of a marine apex predator. Sci. Rep. 11, 3373 (2021).

Pecl, G. T. et al. Redmap Australia: challenges and successes with a large-scale citizen science-based approach to ecological monitoring and community engagement on climate change. Front. Mar. Sci. 6, 11 (2019).

Cheung, W. W., Watson, R. & Pauly, D. Signature of ocean warming in global fisheries catch. Nature 497, 365–368 (2013).

Champion, C., Brodie, S. & Coleman, M. A. Climate-driven range shifts are rapid yet variable among recreationally important coastal-pelagic fishes. Front. Mar. Sci. 8, 622299 (2021).

Harrison, A. L. et al. The political biogeography of migratory marine predators. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2, 1571–1578 (2018).

Pinsky, M. L., Selden, R. L. & Kitchel, Z. J. Climate-driven shifts in marine species ranges: scaling from organisms to communities. Annu. Rev. Mar. Sci. 12, 153–179 (2020).

Pandolfi, J. M., Staples, T. L. & Kiessling, W. Increased extinction in the emergence of novel ecological communities. Science 370, 220–222 (2020).

Poloczanska, E. S. et al. Global imprint of climate change on marine life. Nat. Clim. Change 3, 919–925 (2013).

Lenoir, J. & Svenning, J. C. Climate-related range shifts—a global multidimensional synthesis and new research directions. Ecography 38, 15–28 (2015).

Wernberg, T. et al. Impacts of climate change in a global hotspot for temperate marine biodiversity and ocean warming. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 400, 7–16 (2011).

Fowler, A. M., Parkinson, K. & Booth, D. J. New poleward observations of 30 tropical reef fishes in temperate southeastern Australia. Mar. Biodivers. 48, 2249–2254 (2017).

Verges, A. et al. Long-term empirical evidence of ocean warming leading to tropicalization of fish communities, increased herbivory, and loss of kelp. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 113, 13791–13796 (2016).

Antão, L. H. et al. Temperature-related biodiversity change across temperate marine and terrestrial systems. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 4, 927–933 (2020).

Pigot, A. L. et al. Abrupt expansion of climate change risks for species globally. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 7, 1060–1071 (2023).

Edgar, G. J. et al. Continent-wide declines in shallow reef life over a decade of ocean warming. Nature 615, 858–865 (2023).

Menegotto, A. & Rangel, T. F. Mapping knowledge gaps in marine diversity reveals a latitudinal gradient of missing species richness. Nat. Commun. 9, 4713 (2018).

Edgar, G. J. et al. Establishing the ecological basis for conservation of shallow marine life using Reef Life Survey. Biol. Conserv. 252, 108855 (2020).

Stuart-Smith, R. D. et al. Assessing national biodiversity trends for rocky and coral reefs through the integration of citizen science and scientific monitoring programs. Bioscience 67, 134–146 (2017).

Edgar, G. J. & Barrett, N. S. An assessment of population responses of common inshore fishes and invertebrates following declaration of five Australian marine protected areas. Environ. Conserv. 39, 271–281 (2012).

Day, P. B. et al. Species’ thermal ranges predict changes in reef fish community structure during 8 years of extreme temperature variation. Divers. Distrib. 24, 1036–1046 (2018).

Hughes, T. P. et al. Global warming and recurrent mass bleaching of corals. Nature 543, 373–377 (2017).

Oliver, E. C. J. et al. Marine heatwaves. Ann. Rev. Mar. Sci. 13, 313–342 (2021).

Oliver, E. C. J. et al. The unprecedented 2015/16 Tasman Sea marine heatwave. Nat. Commun. 8, 16101 (2017).

Oliver, E. C. J. et al. Marine heatwaves off eastern Tasmania: trends, interannual variability, and predictability. Prog. Oceanogr. 161, 116–130 (2018).

Johnson, C. R. et al. Climate change cascades: shifts in oceanography, species’ ranges and subtidal marine community dynamics in eastern Tasmania. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 400, 17–32 (2011).

Stuart-Smith, R. D. et al. Ecosystem restructuring along the Great Barrier Reef following mass coral bleaching. Nature 560, 92–96 (2018).

Stuart-Smith, R. D. et al. Stability in temperate reef communities over a decadal time scale despite concurrent ocean warming. Glob. Change Biol. 16, 122–134 (2010).

Maclean, I. M. D. & Early, R. Macroclimate data overestimate range shifts of plants in response to climate change. Nat. Clim. Change 13, 484–490 (2023).

Walker, B. et al. Response diversity as a sustainability strategy. Nat. Sustain. 6, 621–629 (2023).

Brown, S. C. et al. Faster ocean warming threatens richest areas of marine biodiversity. Glob. Change Biol. 28, 5849–5858 (2022).

Chaudhary, C. et al. Global warming is causing a more pronounced dip in marine species richness around the equator. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 118, e2015094118 (2021).

Tewksbury, J. J., Huey, R. B. & Deutsch, C. A. Putting the heat on tropical animals. Science 320, 1296–1297 (2008).

Wright, S. J., Muller-Landau, H. C. & Schipper, J. A. N. The future of tropical species on a warmer planet. Conserv. Biol. 23, 1418–1426 (2009).

Stillman, J. H. Acclimation capacity underlies susceptibility to climate change. Science 301, 65 (2003).

Newbold, T. et al. Tropical and Mediterranean biodiversity is disproportionately sensitive to land-use and climate change. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 4, 1630–1638 (2020).

Waldock, C. et al. The shape of abundance distributions across temperature gradients in reef fishes. Ecol. Lett. 22, 685–696 (2019).

Cahill, A. E. et al. Causes of warm-edge range limits: systematic review, proximate factors and implications for climate change. J. Biogeogr. 41, 429–442 (2014).

Fordham, D. A. et al. Extinction debt from climate change for frogs in the wet tropics. Biol. Lett. 12, 20160236 (2016).

Ziegler, S. L. et al. Marine protected areas, marine heatwaves, and the resilience of nearshore fish communities. Sci. Rep. 13, 1405 (2023).

Caputi, N. et al. Factors affecting the recovery of invertebrate stocks from the 2011 Western Australian extreme marine heatwave. Front. Mar. Sci. 6, 484 (2019).

Smith, K. E. et al. Biological impacts of marine heatwaves. Annu. Rev. Mar. Sci. 15, 119–145 (2023).

Nieblas, A.-E. et al. Variability of biological production in low wind‐forced regional upwelling systems: a case study off southeastern Australia. Limnol. Oceanogr. 54, 1548–1558 (2009).

Fredston-Hermann, A., Gaines, S. D. & Halpern, B. S. Biogeographic constraints to marine conservation in a changing climate. Ann. NY Acad. Sci. 1429, 5–17 (2018).

Alvarez-Noriega, M. et al. Global biogeography of marine dispersal potential. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 4, 1196–1203 (2020).

Assis, J. et al. Major shifts at the range edge of marine forests: the combined effects of climate changes and limited dispersal. Sci. Rep. 7, 44348 (2017).

Marjakangas, E. L. et al. Ecological barriers mediate spatiotemporal shifts of bird communities at a continental scale. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 120, e2213330120 (2023).

Carnell, P. E. & Keough, M. J. More severe disturbance regimes drive the shift of a kelp forest to a sea urchin barren in south-eastern Australia. Sci. Rep. 10, 11272 (2020).

Veenhof, R. J. et al. Urchin grazing of kelp gametophytes in warming oceans. J. Phycol. 59, 838–855 (2023).

McCrea, R. et al. Realising the promise of large data and complex models. Methods Ecol. Evol. 14, 4–11 (2023).

Nathan, R. et al. Big-data approaches lead to an increased understanding of the ecology of animal movement. Science 375, eabg1780 (2022).

Waldock, C. et al. A quantitative review of abundance‐based species distribution models. Ecography 2022, e05694 (2021).

Hughes, T. P. et al. Spatial and temporal patterns of mass bleaching of corals in the Anthropocene. Science 359, 80–83 (2018).

Harris, A. et al. A new high-resolution sea surface temperature blended analysis. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 98, 1015–1026 (2017).

Pebesma, E. J. Multivariable geostatistics in S: the gstat package. Comput. Geosci. 30, 683–691 (2004).

Dowle, M. S. A. data.table: extension of ‘data.frame’. R package version 1.9.2. CRAN https://doi.org/10.32614/CRAN.package.data.table (2023).

Wickham, H. et al. Welcome to the Tidyverse. J. Open Source Softw. 4, 1686 (2019).

Herrera Fuchs, Y. Range shifts. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.12817835 (2024).

Acknowledgements

Support for field surveys was provided by the Australian Research Council; the Australian Institute of Marine Science; the Institute for Marine and Antarctic Studies; Parks Australia; Department of Natural Resources and Environment Tasmania; New South Wales Department of Primary Industries; Parks Victoria; South Australia Department of Environment, Water and Natural Resources; Western Australia Department of Biodiversity, Conservation and Attractions; The Ian Potter Foundation; Minderoo Foundation; and the Marine Biodiversity Hub, a collaborative partnership supported through the Australian Government’s National Environmental Science Programme. R.D.S.-S. was supported by ARC FT190100599. We thank the many colleagues and RLS divers who participated in data collection, and Antonia Cooper and Elizabeth Oh for data management. RLS and ATRC data management is supported by Australia’s Integrated Marine Observing System (IMOS)—IMOS is enabled by the National Collaborative Research Infrastructure Strategy. We are also grateful to the data curators of the NOAA Coral Reef Watch programme for managing extensive datasets and making them available to the public.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.H.F. developed the analysis, code script and manuscript under supervision from R.D.S.-S. and G.J.E. R.D.S.-S. guided research questions and article structure. G.J.E. conceptualized methods to estimate range edges on the basis of abundance-weighted quantiles. A.E.B. and C.W. provided statistical support. All authors contributed to key ideas and interpretation.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Climate Change thanks Manuel Hidalgo and Joice Silva de Souza for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Extended Data Fig. 1 Latitudinal distribution of range shifts.

Density curves show equatorward (dark grey) and poleward (light grey) range shifts where displacement was greater than 1° at warm and cool edges.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Temperature fluctuations of Solitary and Lord Howe Islands.

Yearly averages of sea-surface temperature (SST) fluctuations for sites in Solitary Islands and Lorde Howe Island. Dashed lines indicate the date of the first year and last year these sites were surveyed, which are the two time points used to calculate site-level temperature and latitudinal limit changes in these locations.

Extended Data Fig. 3 Regional latitudinal shifts using data from 2010–2015 and 2016–2021.

a) Number of sites included in analysis per region and period each year. b) Replication of Fig. 3 using averages from all the years a site was surveyed at the two time periods. Positive values in warm and cool edges indicate range expansion and contraction, respectively. Asterisks (*) signal two-sided t-tests where p < 0.05 (mu = 0), for tropical and temperate species. Geographic restrictions for range shift detectability are presented as circles (no restriction), triangles (north coast sampling barrier) and squares (Southern Ocean habitat barrier). Data are presented as mean range shift values ± SEM in each region where N range edges > 10.

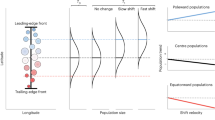

Extended Data Fig. 4 Conceptual diagram of range edge estimation.

a) Warm (red) and cool (blue) limits were estimated for a species range from b) the latitudes associated with the 5th and 95th percentiles (black dashed lines) of cumulative abundance for a species distribution. See Methods for details.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Tables

Supplementary Tables 1 and 2.

Source data

Source Data Figs. 1–3, Extended Data Figs. 1–4, Extended Data Tables 1–4 and Supplementary Tables 1 and 2

Summarized datasets with range edge calculations for Figs. 1–3, Extended Data Figs. 1–4, Extended Data Tables 1–4 and Supplementary Tables 1 and 2.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Fuchs, Y.H., Edgar, G.J., Bates, A.E. et al. Limited net poleward movement of reef species over a decade of climate extremes. Nat. Clim. Chang. 14, 1087–1092 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-024-02116-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-024-02116-w

This article is cited by

-

The fishes of Gamay (Botany Bay): combining multiple data sources to characterise assemblage structure in an Australian urbanised estuary

Marine Biology (2026)

-

Tropical reefs in the aftermath of climate change

Discover Conservation (2025)