Abstract

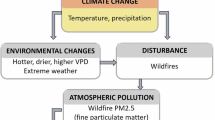

Climate change intensifies fire smoke, emitting hazardous air pollutants that impact human health. However, the global influence of climate change on fire-induced health impacts remains unquantified. Here we used three well-tested fire–vegetation models in combination with a chemical transport model and health risk assessment framework to attribute global human mortality from fire fine particulate matter (PM2.5) emissions to climate change. Of the 46,401 (1960s) to 98,748 (2010s) annual fire PM2.5 mortalities, 669 (1.2%, 1960s) to 12,566 (12.8%, 2010s) were attributed to climate change. The most substantial influence of climate change on fire mortality occurred in South America, Australia and Europe, coinciding with decreased relative humidity and in boreal forests with increased air temperature. Increasing relative humidity lowered fire mortality in other regions, such as South Asia. Our study highlights the role of climate change in fire mortality, aiding public health authorities in spatial targeting adaptation measures for sensitive fire-prone areas.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$32.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $21.58 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

Input data (climate and socio-economic forcing and the burnt area in the factual and counterfactual simulations) are available from the ISIMIP data repository (https://data.isimip.org/). Topographic data for making global map were from MathWorks and we used MATLAB R2024a for creating all figures. Intermediate and output data used in this analysis are available at the repository in both MATLAB array and NetCDF formats77. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

All code to reproduce the analysis and figures is available via Zenodo at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.13231638 (ref. 77).

Change history

25 October 2024

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-024-02195-9

References

Rodrigues, M. et al. Drivers and implications of the extreme 2022 wildfire season in southwest Europe. Sci. Total Environ. 859, 160320 (2023).

McArdle, C. E. et al. Asthma-associated emergency department visits during the Canadian wildfire smoke episodes—United States, April–August 2023. Morb. Mortal. Wkly Rep. 72, 926–932 (2023).

Johnston, F. H. et al. Unprecedented health costs of smoke-related PM2.5 from the 2019–20 Australian megafires. Nat. Sustain. 4, 42–47 (2021).

Cohen, A. J. et al. Estimates and 25-year trends of the global burden of disease attributable to ambient air pollution: an analysis of data from the Global Burden of Diseases Study 2015. Lancet 389, 1907–1918 (2017).

Lelieveld, J., Haines, A. & Pozzer, A. Age-dependent health risk from ambient air pollution: a modelling and data analysis of childhood mortality in middle-income and low-income countries. Lancet Planet Health 2, e292–e300 (2018).

Burnett, R. et al. Global estimates of mortality associated with long-term exposure to outdoor fine particulate matter. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 115, 9592–9597 (2018).

Weagle, C. L. et al. Global sources of fine particulate matter: interpretation of PM2.5 chemical composition observed by SPARTAN using a global chemical transport model. Environ. Sci. Technol. 52, 11670–11681 (2018).

Lelieveld, J., Evans, J. S., Fnais, M., Giannadaki, D. & Pozzer, A. The contribution of outdoor air pollution sources to premature mortality on a global scale. Nature 525, 367–371 (2015).

McDuffie, E. E. et al. Source sector and fuel contributions to ambient PM2.5 and attributable mortality across multiple spatial scales. Nat. Commun. 12, 3594 (2021).

Johnston, F. H. et al. Estimated global mortality attributable to smoke from landscape fires. Environ. Health Perspect. 120, 695–701 (2012).

Roberts, G. & Wooster, M. J. Global impact of landscape fire emissions on surface level PM2.5 concentrations, air quality exposure and population mortality. Atmos. Environ. 252, 118210 (2021).

Arora, V. K. & Melton, J. R. Reduction in global area burned and wildfire emissions since 1930s enhances carbon uptake by land. Nat. Commun. 9, 1326 (2018).

Andela, N. et al. A human-driven decline in global burned area. Science 356, 1356–1362 (2017).

Jolly, W. M. et al. Climate-induced variations in global wildfire danger from 1979 to 2013. Nat. Commun. 6, 7537 (2015).

Abatzoglou, J. T., Williams, A. P. & Barbero, R. Global emergence of anthropogenic climate change in fire weather indices. Geophys. Res. Lett. 46, 326–336 (2019).

Jones, M. W. et al. Global and regional trends and drivers of fire under climate change. Rev. Geophys. 60, e2020RG000726 (2022).

Jain, P., Castellanos-Acuna, D., Coogan, S. C. P., Abatzoglou, J. T. & Flannigan, M. D. Observed increases in extreme fire weather driven by atmospheric humidity and temperature. Nat. Clim. Change 12, 63–70 (2022).

Kloster, S. et al. Fire dynamics during the 20th century simulated by the Community Land Model. Biogeosciences 7, 1877–1902 (2010).

Flannigan, M. D., Stocks, B. J. & Wotton, B. M. Climate change and forest fires. Sci. Total Environ. 262, 221–229 (2000).

Kollanus, V. et al. Mortality due to vegetation fire-originated PM 2.5 exposure in Europe—assessment for the years 2005 and 2008. Environ. Health Perspect. 125, 30–37 (2017).

Koplitz, S. N. et al. Public health impacts of the severe haze in equatorial Asia in September–October 2015: demonstration of a new framework for informing fire management strategies to reduce downwind smoke exposure. Environ. Res. Lett. 11, 094023 (2016).

Crippa, P. et al. Population exposure to hazardous air quality due to the 2015 fires in equatorial Asia. Sci. Rep. 6, 37074 (2016).

Swanson, K. L., Sugihara, G. & Tsonis, A. A. Long-term natural variability and 20th century climate change. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 106, 16120–16123 (2009).

Frieler, K. et al. Scenario setup and forcing data for impact model evaluation and impact attribution within the third round of the Inter-Sectoral Model Intercomparison Project (ISIMIP3a). Geosci. Model Dev. 17, 1–51 (2024).

IPCC: Summary for Policymakers. In Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability (eds H.-O. Pörtner, H.-O. et al.) 3–34 (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2022).

Mengel, M., Treu, S., Lange, S. & Frieler, K. ATTRICI v1.1—counterfactual climate for impact attribution. Geosci. Model Dev. 14, 5269–5284 (2021).

Jones, M. W. et al. Fires prime terrestrial organic carbon for riverine export to the global oceans. Nat. Commun. 11, 2791 (2020).

Freitas, S. R. et al. Monitoring the transport of biomass burning emissions in South America. Environ. Fluid Mech. 5, 135–167 (2005).

van der Velde, I. R. et al. Vast CO2 release from Australian fires in 2019–2020 constrained by satellite. Nature 597, 366–369 (2021).

Abram, N. J. et al. Connections of climate change and variability to large and extreme forest fires in southeast Australia. Commun. Earth Environ. 2, 8 (2021).

Turco, M., Llasat, M. C., von Hardenberg, J. & Provenzale, A. Climate change impacts on wildfires in a Mediterranean environment. Clim. Change 125, 369–380 (2014).

Dupuy, J. L. et al. Climate change impact on future wildfire danger and activity in southern Europe: a review. Ann. For. Sci. 77, 35 (2020).

Gaboriau, D. M., Asselin, H., Ali, A. A., Hély, C. & Girardin, M. P. Drivers of extreme wildfire years in the 1965–2019 fire regime of the Tłı̨chǫ First Nation territory, Canada. Écoscience 29, 249–265 (2022).

Zeng, H., Jia, G. & Epstein, H. Recent changes in phenology over the northern high latitudes detected from multi-satellite data. Environ. Res. Lett. 6, 045508 (2011).

Chia, S. Y. & Lim, M. W. A critical review on the influence of humidity for plant growth forecasting. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 1257, 012001 (2022).

Archibald, S. Managing the human component of fire regimes: lessons from Africa. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B 371, 20150346 (2016).

Agbola, S. B. & Falola, O. J. Seasonal and locational variations in fire disasters in Ibadan, Nigeria. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 54, 102035 (2021).

Butt, E. W. et al. Global and regional trends in particulate air pollution and attributable health burden over the past 50 years. Environ. Res. Lett. 12, 104017 (2017).

Archibald, S. et al. Biological and geophysical feedbacks with fire in the Earth system. Environ. Res. Lett. 13, 033003 (2018).

Abatzoglou, J. T., Williams, A. P., Boschetti, L., Zubkova, M. & Kolden, C. A. Global patterns of interannual climate–fire relationships. Glob. Change Biol. 24, 5164–5175 (2018).

Marengo, J. A. et al. Recent extremes of drought and flooding in Amazonia: vulnerabilities and human adaptation. Am. J. Clim. Change 02, 87–96 (2013).

Libonati, R. et al. Assessing the role of compound drought and heatwave events on unprecedented 2020 wildfires in the Pantanal. Environ. Res. Lett. 17, 015005 (2022).

Ellis, T. M., Bowman, D. M. J. S., Jain, P., Flannigan, M. D. & Williamson, G. J. Global increase in wildfire risk due to climate‐driven declines in fuel moisture. Glob. Change Biol. 28, 1544–1559 (2022).

Shinoda, M. & Yamaguchi, Y. Influence of soil moisture anomaly on temperature in the Sahel: a comparison between wet and dry decades. J. Hydrometeorol. 4, 437–447 (2003).

Li, F., Zeng, X. D. & Levis, S. A process-based fire parameterization of intermediate complexity in a dynamic global vegetation model. Biogeosciences 9, 2761–2780 (2012).

Aldersley, A., Murray, S. J. & Cornell, S. E. Global and regional analysis of climate and human drivers of wildfire. Sci. Total Environ. 409, 3472–3481 (2011).

Burton, C. et al. Global burned area increasingly explained by climate change. Preprint at Research Square https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-3168150/v1 (2024).

Krewski, D. et al. Extended Follow-Up and Spatial Analysis of the American Cancer Society Study Linking Particulate Air Pollution and Mortality: Special Report (Health Effects Institute, 2009).

Chen, G. et al. Mortality risk attributable to wildfire-related PM2·5 pollution: a global time series study in 749 locations. Lancet Planet Health 5, e579–e587 (2021).

Taming Wildfires in the Context of Climate Change (OECD, 2023).

Lange, S., Mengel, M., Treu, S. & Büchner, M. ISIMIP3a atmospheric climate input data. ISIMIP Repository https://doi.org/10.48364/ISIMIP.982724.1 (2022).

Volkholz, J., Lange, S. & Geiger, T. ISIMIP3a population input data. ISIMIP Repository https://doi.org/10.48364/ISIMIP.822480.2 (2022).

Volkholz, J. & Ostberg, S. ISIMIP3a landuse input data (v1.1). ISIMIP Repository https://doi.org/10.48364/ISIMIP.571261.1 (2022).

World Population Prospects 2022: Data Sources. UN DESA/POP/2022/DC/NO. 9 (UN, 2022).

Global Burden of Disease Study 2019 (GBD 2019) Results (IHME, 2020); http://ghdx.healthdata.org/gbd-results-tool

Hoesly, R. M. et al. Historical (1750–2014) anthropogenic emissions of reactive gases and aerosols from the Community Emissions Data System (CEDS). Geosci. Model Dev. 11, 369–408 (2018).

MERRA-2 3D IAU State, Meteorology 3-Hourly (p-coord, 0.625x0.5L42) version 5.12.4 (GSFC DAAC, 2015).

Bey, I. et al. Global modeling of tropospheric chemistry with assimilated meteorology: model description and evaluation. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 106, 23073–23095 (2001).

Global Burden of Disease Study 2019 (GBD 2019) Particulate Matter Risk Curves (IHME, 2021).

Rosenzweig, C. et al. Assessing inter-sectoral climate change risks: the role of ISIMIP. Environ. Res. Lett. 12, 010301 (2017).

Cecil, D. J. LIS/OTD 0.5 Degree High Resolution Monthly Climatology (HRMC) V2.3.2015 (NASA, 2006); https://cmr.earthdata.nasa.gov/search/concepts/C1995863290-GHRC_DAAC.html

Arora, V. K. & Boer, G. J. Fire as an interactive component of dynamic vegetation models. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosci. 110, G2 (2005).

Melton, J. R. et al. CLASSIC v1.0: the open-source community successor to the Canadian Land Surface Scheme (CLASS) and the Canadian Terrestrial Ecosystem Model (CTEM)—Part 1: model framework and site-level performance. Geosci. Model Dev. 13, 2825–2850 (2020).

Huang, H., Xue, Y., Li, F. & Liu, Y. Modeling long-term fire impact on ecosystem characteristics and surface energy using a process-based vegetation-fire model SSiB4/TRIFFID-Fire v1.0. Geosci. Model Dev. 13, 6029–6050 (2020).

Mangeon, S. et al. INFERNO: a fire and emissions scheme for the UK Met Office’s Unified Model. Geosci. Model Dev. 9, 2685–2700 (2016).

Park, C. Y. et al. Impact of climate and socioeconomic changes on fire carbon emissions in the future: sustainable economic development might decrease future emissions. Glob. Environ. Change 80, 102667 (2023).

Li, F. et al. Historical (1700–2012) global multi-model estimates of the fire emissions from the Fire Modeling Intercomparison Project (FireMIP). Atmos. Chem. Phys. 19, 12545–12567 (2019).

Rabin, S. S. et al. The Fire Modeling Intercomparison Project (FireMIP), phase 1: experimental and analytical protocols with detailed model descriptions. Geosci. Model Dev. 10, 1175–1197 (2017).

Parrella, J. P. et al. Tropospheric bromine chemistry: implications for present and pre-industrial ozone and mercury. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 12, 6723–6740 (2012).

Mao, J., Fan, S., Jacob, D. J. & Travis, K. R. Radical loss in the atmosphere from Cu–Fe redox coupling in aerosols. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 13, 509–519 (2013).

Jansakoo, T. et al. Comparison of global air pollution impacts across horizontal resolutions. Preprint at SSRN https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4856924 (2023).

Sakaguchi, K. et al. Technical descriptions of the experimental dynamical downscaling simulations over North America by the CAM–MPAS variable-resolution model. Geosci. Model Dev. 16, 3029–3081 (2023).

Southerland, V. A. et al. Global urban temporal trends in fine particulate matter (PM2·5) and attributable health burdens: estimates from global datasets. Lancet Planet Health 6, e139–e146 (2022).

Lind, L., Sundström, J., Ärnlöv, J. & Lampa, E. Impact of aging on the strength of cardiovascular risk factors: a longitudinal study over 40 years. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 7, e007061 (2018).

Kelley, D. I. et al. A comprehensive benchmarking system for evaluating global vegetation models. Biogeosciences 10, 3313–3340 (2013).

Hantson, S. et al. Quantitative assessment of fire and vegetation properties in simulations with fire-enabled vegetation models from the Fire Model Intercomparison Project. Geosci. Model Dev. 13, 3299–3318 (2020).

Park, C. Y. et al. Attributing human mortality from fire PM2.5 to climate change [Data set]. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.13231638 (2024).

Acknowledgements

C.Y.P., K.T. and S.F. were supported by the Environment Research and Technology Development Fund (JPMEERF20241001) of the Environmental Restoration and Conservation Agency of Japan. C.Y.P. was supported by JSPS KAKENHI grant no. JP24H01530. S.F. and T.J. were supported by the Sumitomo Electric Industries Group CSR Foundation. C.B. was funded by the Met Office Climate Science for Service Partnership Brazil project which is supported by the Department for Science, Innovation & Technology. H.H. was supported by United States Department of Energy, Office of Science (Lab Directed Res & Dev (LDRD) 29IN290162:80941). PNNL is operated for DOE by Battelle Memorial Institute under contract DE-ACO5-76RL01830. M.M. was supported by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research under the research projects QUIDIC (01LP1907A) and is based on work from COST Action CA19139 PROCLIAS (process-based models for climate impact attribution across sectors), supported by COST (European Cooperation in Science and Technology; https://www.cost.eu). S.H. was supported by the Max Planck Tandem group programme. D.K.L. was supported by the Korea Environment Industry & Technology Institute through the ‘Climate Change R&D Project for New Climate Regime’ funded by the Korea Ministry of Environment (2022003570004).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.Y.P. contributed to analysis and writing. K.T., S.F., C.P.O.R. and M.M. contributed to the design of the study. T.J., C.B., H.H., S.K.-G. and E.B. ran the atmospheric model or fire–vegetation model simulations and contributed data. F.L., S.H. and C.B. coordinated the fire sector in ISIMIP with the support of C.P.O.R. J.T., D.K.L. and T.H. contributed to statistical analysis and reviewed the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Climate Change thanks Hamish Clarke, Jennifer Stowell and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

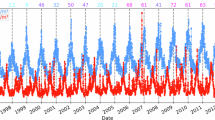

Extended Data Fig. 1 Fire organic carbon emissions from three fire-vegetation models.

Annual total organic carbon (OC) emissions from three fire models (a, CLASSIC; b, SSiB4; and c, JULES) and observation-based reference data (GFED4.1 s [Global Fire Emissions Database version 4.1] for 1997–2019 (d) and together with GFAS [CAMS Global Fire Assimilation System] for 2003–2019 (e)). OC is the predominant particulate carbon from fire. Three fire-vegetation models (a, b, and c) have two simulation results (factual simulation (1) and counterfactual simulation (2)) and the attribution of climate change (ACC) (3). JULES considered fires in both cropland and pastureland as agricultural fires, while CLASSIC considered only fires in cropland.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Notes 1–3, Figs. 1–9, Tables 1 and 2 and references.

Source data

Source Data Fig. 1

Source data for bar chart.

Source Data Fig. 2

Source data for mapping changes.

Source Data Fig. 3

Source data for bar chart.

Source Data Fig. 4

Source data for mapping changes.

Source Data Fig. 5

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 1

Source data for plotting.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Park, C.Y., Takahashi, K., Fujimori, S. et al. Attributing human mortality from fire PM2.5 to climate change. Nat. Clim. Chang. 14, 1193–1200 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-024-02149-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-024-02149-1

This article is cited by

-

Health losses attributed to anthropogenic climate change

Nature Climate Change (2025)

-

Anthropogenic climate change contributes to wildfire particulate matter and related mortality in the United States

Communications Earth & Environment (2025)

-

Growing human-induced climate change fingerprint in regional weekly fire extremes

npj Climate and Atmospheric Science (2025)

-

Large reductions in tropical bird abundance attributable to heat extreme intensification

Nature Ecology & Evolution (2025)

-

Air temperature estimation and modeling using data driven techniques based on best subset regression model in Egypt

Scientific Reports (2025)