Abstract

The assumption that crop-land natural climate solutions (NCS) have benefits for both climate change mitigation and crop production remains largely untested. Here we model GHG emissions and crop yields from crop-land NCS through the end of the century. We find that favourable (win–win) outcomes were the exception not the norm; grass cover crops with no tillage lead to cumulative global GHG mitigation of 32.6 Pg CO2 equivalent, 95% confidence interval (29.5, 35.7), by 2050 but reduce cumulative crop yields by 4.8 Pg, 95% confidence interval (4.0, 5.7). Legume cover crops with no tillage result in favourable outcomes through 2050 but increase GHG emissions for some regions by 2100. Crop-lands with low soil nitrogen and high clay are more likely to have favourable outcomes. Avoiding crop losses, we find modest GHG mitigation benefits from crop-land NCS, 4.4 Pg CO2 equivalent, 95% confidence interval (4.2, 4.6) by 2050, indicating crop-land soil will constitute a fraction of food system decarbonization.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Natural climate solutions (NCS) are deliberate human actions that protect, restore and improve management of land and oceans to mitigate climate change1. They are considered an essential tool for mitigating climate change in this century2,3. However, a possible consequence of widespread adoption of these actions on crop-lands is yield losses, leading to land-use change to meet food demand, undermining climate change mitigation and other sustainable development goals. Crop-land NCS should preferably sustain or increase crop yields to avoid additional land conversion4.

In experimental studies, crop-land NCS practices have been reported to produce variable outcomes for yield and GHG mitigation, especially in the initial years after adoption5,6,7,8,9. At larger scales, long-term trade-offs between yield and mitigation goals are largely unknown. Prior empirical analyses provided some protections for the global food supply by avoiding reforestation in crop-lands, but, nonetheless, assessments are lacking about how crop-land NCS directly impact crop yields1,10. Process-based modelling can help fill this gap.

Additionally, assessments of the climate change mitigation potential of these practices often focus only on soil organic carbon (SOC) responses1,10,11,12,13,14,15,16. Meta-analyses and regional modelling suggest that the net GHG mitigation benefit of adopting NCS for SOC storage, which removes CO2 from the atmosphere, may be partially negated by growth in soil N2O emissions6,17,18, a GHG that has a global warming potential of 273 relative to CO2 over a 100-year time horizon. Despite these research gaps, there is growing momentum across the public and private spheres to rapidly adopt NCS practices to address climate change with the assumption that yield and other ‘regenerative’ co-benefits will follow.

Cover cropping is viewed as a widely favourable NCS in crop-lands. Cover crops increase SOC through higher net primary production in annual cropping system rotations7,19,20. Cover crops also uptake excess nitrogen fertilizer, oftentimes reducing N2O (and nitrate) losses7,21. But the choice of cover crop functional type—especially the distinction between leguminous or non-leguminous species—can impact soil C sequestration and N dynamics in different management and soil conditions19,22. Observed impacts of cover crops on crop yields vary depending on initial SOC, cover crop functional type, cropping system and tillage management7,8,9. Combining cover crops and no tillage together, which reduces soil disturbance, may lead to better environmental and production outcomes5,23. However, the mitigation potential for cover crops and no tillage is either reported separately or assumed to be additive by combining global meta-analysis effect sizes for individual practices11.

Here we compared global and regional outcomes of immediate 100% adoption of these NCS practices compared to GHG and yield responses under continued, conventional crop-land management, that is, fallow and tillage, using a process-based model. This resulted in four crop-land NCS scenarios, adoption of grass or legume cover crops with conventional tillage or no tillage, all of which included full residue retention of cover and cash crop biomass. We also evaluated the efficacy of these individual and combined NCS practices in the context of a changing climate and over multi-decadal time frames to 2100, these extended time frames being critical to assessing the longer-term impacts of practices that must be maintained indefinitely to ensure that carbon remains stored in SOC24,25,26.

The objectives of our study were to: (1) identify scenarios that led to favourable GHG mitigation and yield outcomes over the near and medium terms (defined as mid-century and end of century, respectively), (2) determine environmental and management drivers of favourable outcomes and (3) quantify the potential costs (trade-offs) that arise from adopting crop-land NCS maximizing for GHG mitigation or yield outcomes or adoption that balances both climate change mitigation and crop production goals.

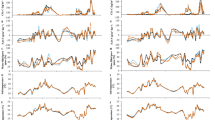

Favourable climate and production outcomes are not ubiquitous

Our model analysis shows that it is not possible to simultaneously maximize global GHG mitigation and yield benefits from crop-land NCS (Fig. 1). The highest modelled GHG mitigation potential is under the adoption of grass cover crops with no tillage (universal adoption), with a near-term (2016–2050) cumulative mitigation of 32.6 Pg CO2 equivalent (CO2-eq), 95% confidence interval (CI) (29.5, 35.7) and a medium-term (2016–2100) cumulative mitigation of 41.3 Pg CO2-eq, 95% CI (35.4, 47.2) (annual values in Fig. 1). However, this GHG mitigation comes at the cost of reducing crop yields by a cumulative 4.8 Pg of dry mass, 95% CI (4.0, 5.7) and 8.2 Pg, 95% CI (6.2, 10.1), respectively. Whereas legume cover crops with no tillage results in higher yields, 6.2 Pg, 95% CI (4.8, 7.7), and 19.3 Pg, 95% CI (15.4, 23.2), in near and medium terms, respectively, the mean GHG mitigation potential is 7% lower than grass cover crops with no tillage in the near term (significant at a 95% CI based on one-sided difference bootstrap significance test). Notably, the GHG mitigation potential of legume cover crops with no tillage is 69% lower than grass cover crop with no tillage over the medium term because of elevated soil N2O emissions and declining soil carbon storage (Fig. 1 and Supplementary Figs. 1–3).

The nature of this GHG mitigation and crop yield trade-off varies spatially (Fig. 2 and Extended Data Figs. 1−3). Around 90% of the modelled GHG mitigation potential from grass cover crops with no tillage is in developed countries (DEV; 13.1 Pg CO2-eq, 95% CI (12.2, 14.0), in the near term and 20.0 Pg CO2-eq, 95% CI (18.3, 21.7), in the medium term) followed by Latin America and Caribbean (LAC) countries and Asia and Developing Pacific (ADP) countries. However, these regions also experience the highest yield reductions, 2.4 Pg, 95% CI (2.2, 2.7), 0.9 Pg, 95% CI (0.8, 1.0) and 0.6 Pg, 95% CI (0.3, 1.0), lower in the near term, respectively, and similar differences in the medium term. The GHG mitigation potential of grass cover crops with no tillage is lowest in Africa and Middle East (AME) countries and East Europe and West–Central Asia (EEWCA) countries, but crop yield impacts are more heterogeneous, and generally, there are smaller yield reductions in these regions. The magnitude of mitigation potential in each region largely arises due to the amount of crop-land area, but per-hectare responses usually follow a similar trend across all regions (Supplementary Figs. 1–4). We note that the coefficient of variation of the modelled hectare-level responses tends to be lower in DEV countries (typically across all scenarios) but is much higher in other regions (Supplementary Figs. 5 and 6).

a,b, Grass CC (GHG (a); yield (b)). c,d, Grass CC + Ntill (GHG (c); yield (d)). e,f, Legume CC (GHG (e); yield (f)). g,h, Legume CC + Ntill (GHG (g); yield (h)). Base map data in a–h from The World Bank under a Creative Commons license CC BY 4.0.

Grass cover crops with tillage have a lower global GHG mitigation potential than with no tillage but also a reduced (albeit still negative) impact on crop productivity (Figs. 1 and 2). Cumulative GHG mitigation potential is highest in DEV and LAC countries in the near term, 4.0 Pg CO2-eq, 95% CI (3.5, 4.4), and 3.6 Pg CO2-eq, 95% CI (2.9, 4.3), respectively, but medium-term GHG mitigation potential in LAC countries is 56% lower compared with the near term because of decreasing soil C sequestration rates. The negative effect of grass cover crops with tillage on crop yields in DEV countries is reduced by 74% in the near term and 80% in the medium term compared to grass cover crops with no tillage (Supplementary Fig. 4). The heterogeneity in yield responses to grass cover crops in AME, ADP and EEWCA countries results in smaller yield reductions at the regional scale in the near term and a small crop yield benefit in AME and EEWCA countries in the medium term (Fig. 1 and Extended Data Figs. 1−3).

Adopting no tillage with legume cover crops attenuates the elevated soil N2O emissions associated with biological N fixation offsetting these emissions through higher soil carbon storage. Modelled near-term global GHG mitigation potential is 30.3 Pg CO2-eq, 95% CI (27.9, 32.7), whereas in the medium term, it is 12.9 Pg CO2-eq, 95% CI (8.0, 17.8) (Fig. 1). Unlike grass cover crops, legume cover crops have a positive effect on crop yields; global modelled crop yields in the near term are 6.2 Pg, 95% CI (4.8, 7.7), higher than continued crop-land management practices, and this effect increases over time where medium-term crop yields are 19.3 Pg, 95% CI (15.4, 23.2), higher. Regionally, DEV countries are almost 40% of the global GHG mitigation potential in the near term, and moreover, DEV countries account for nearly all of the global GHG mitigation potential in the medium term. While lower in the near term, crop yields are about 1.0 Pg, 95% CI (0.3, 1.8), higher in DEV countries in the medium term. However, while crop yield benefits become more apparent over time with this scenario, especially in LAC and AME countries, legume cover crops with no tillage do not always lead to medium-term GHG mitigation (that is, AME and ADP countries).

Whereas legume cover crops with tillage lead to higher yields than with no tillage, especially over the near term, GHG mitigation potential is considerably lower and even a source of GHG emissions. Specifically, global crop yields are 38% higher and 22% higher in the near and medium terms, respectively, compared to legume cover crops with no tillage. While highly variable, legume cover crops with tillage are a small global net source of emissions in the near term, 0.4 Pg CO2-eq, 95% CI (−1.7, 2.4). Over the medium term there is a stronger global signal with GHG emissions that are 36.9 Pg CO2-eq, 95% CI (31.3, 42.6), higher than continued crop-land management practices, largely arising from higher emissions in ADP countries.

Drivers of favourable climate and crop yield outcomes

The variation in outcomes suggests that climate, soil and management features drive GHG mitigation and crop responses to crop-land NCS. To identify and rank the importance of these features, we used SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP values) to explain feature importance for predicting joint-outcome classifications in random forest models for each crop-land NCS scenario (Supplementary Table 1). Below, we focus on the conditions that lead to favourable outcomes for end-of-century climate change mitigation and crop yield benefits (additional outcomes in Supplementary Fig. 7).

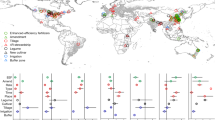

The most important features for predicting favourable outcomes across all the crop-land NCS scenarios are related to soil properties, cropping system and nitrogen (Fig. 3). Management-related features, such as cash crop type, water management, nitrogen application and initial residue retention fraction, frequently contribute to the likelihood of favourable outcomes. Soil bulk density, which is highly correlated with soil texture (that is, clay content), and initial soil nitrate content are also key features probably because of the influence of soil physical properties on soil C stabilization and on crop growth in the model. Climate-related variables, such as mean diurnal range, are not ranked among the top features for any of the scenarios.

There is an increased likelihood of favourable outcomes in maize and wheat compared to soybean cropping systems, which is probably a factor of additional N from N fixation provided by legume cover crops (Fig. 4). Irrigated cropping systems are also more likely to have favourable outcomes by alleviating water limitation. The response across crop-land NCS scenarios to nitrogen applications (fertilizer and manure) and initial residue retention amounts are more varied; the highest rates of N application and residue retention are more likely to lead to benefits for grass cover crops with tillage and legume cover crops with no tillage but not for legume cover crops with tillage.

Positive SHAP value indicates higher likelihood of favourable outcome. Lines and points are mean SHAP values for continuous and categorical features, respectively. Figure 3 provides key to feature colours. a–e, Grass CC (soil bulk density (a); initial soil nitrate (b); initial residue fraction (c); water management (d); cash crop (e)). f–j, Grass CC + Ntill (soil bulk density (f); cash crop (g); initial soil nitrate (h); water management (i); initial residue fraction (j)). k–o, Legume CC (cash crop (k); water management (l); nitrate fertilizer fraction (m); nitrogen inputs (n); initial soil nitrate (o)). p–t, Legume CC + Ntill (cash crop (p); initial soil nitrate (q); soil bulk density (r); nitrogen inputs (s); initial residue fraction (t)).

Balancing climate and crop benefits from crop-land NCS

Rapid scaling of crop-land NCS practices can be supported with spatially explicit adoption recommendations based on mutually beneficial mitigation and crop production outcomes. The results above suggest that these recommendations will vary in space and time depending upon desired goals; more sustainable outcomes will avoid compromising yield for GHG mitigation (or vice versa).

We find that pursuing a goal of maximum GHG mitigation, but ignoring crop yield impacts, results in global near-term GHG mitigation of 35.6 Pg CO2-eq, 95% CI (32.8, 38.5) and medium-term GHG mitigation of 44.0 Pg CO2-eq, 95% CI (38.4, 49.6) (Extended Data Fig. 4). Most of this potential is attributed to the adoption of grass cover crops with no tillage across all regions. However, while the mean crop yield impact is positive in the near term, 2.3 Pg, 95% CI (1.4, 3.3), global crop yields are 3.6 Pg, 95% CI (1.6, 5.6), lower in the medium term. Regionally, the highest near- and medium-term GHG mitigation potential is concentrated in DEV countries, but crop yields are 1.6 Pg, 95% CI (1.3, 1.8), lower in the near term and 3.5 Pg, 95% CI (2.9, 4.0), lower in the medium term (Fig. 5). EEWCA is the only region with clear GHG and yield benefit outcomes through the medium term.

Annual mean estimates with 95% CI are reported for the near term, 2016–2050, and medium term, 2016–2100 (n = 24). Positive values indicate GHG mitigation or higher yields whereas negative values indicate GHG emissions or lower yields relative to continued management practices. Base map data from The World Bank under a Creative Commons license CC BY 4.0.

Likewise, pursuing a goal of maximum crop yield but ignoring GHG impacts leads to 9.6 Pg, 95% CI (8.3, 10.9), and 25.5 Pg, 95% CI (21.9, 29.1), higher crop yields in the near and medium terms, respectively (Extended Data Fig. 4). Under this goal, the recommended scenario for most crop-land is to adopt legume cover crops with tillage. Most of this potential is found in LAC countries (10.4 Pg, 95% CI (9.4, 11.4), in medium term) followed by AME countries (5.6 Pg, 95% CI (4.8, 6.4), in medium term). However, pursuing a maximum crop yield goal has modest (and variable) GHG mitigation potential of 1.4 Pg CO2-eq, 95% CI (−0.2, 2.9), in the near term but increases GHG emissions by 20.1 Pg CO2-eq, 95% CI (15.7, 24.5), over the medium term, with almost 40% of these emissions attributed to AME countries.

Balancing both climate and production goals substantially reduces the benefits of crop-land NCS (Fig. 5). Restricting adoption recommendations to Pareto-optimal practices that maximize climate benefits without sacrificing any reduction in crop yields, leads to near-term global GHG mitigation of 4.4 Pg CO2-eq, 95% CI (4.2, 4.6) (Extended Data Fig. 4). Conversely, adopting only practices that maximize crop yields without sacrificing an increase in GHG emissions leads to a near-term global GHG mitigation of 4.1 Pg CO2-eq, 95% CI (3.7, 4.4). Near-term global crop benefits range from 3.8 Pg, 95% CI (3.7, 3.9), under a goal of maximum GHG mitigation (no crop yield reductions) to 5.6 Pg, 95% CI (5.3, 6.0) under a goal of maximum crop yields (no GHG emissions increases; Extended Data Fig. 4). This is a reduction of about 87% of the maximum GHG mitigation potential from crop-land NCS and of up to 60% of the maximum yield benefit in the near term; this is because in many instances no crop-land NCS practices lead to favourable outcomes, and we assume a continuation of conventional management practices. Under the balanced goals in the medium term, global GHG mitigation potential from crop-land NCS are 85–98% lower than the maximum GHG mitigation estimate, and global yield benefits are 79–90% lower than the maximum yield benefit estimate. LAC and DEV countries generally have the highest mitigation and crop production benefits (Fig. 5 and Extended Data Fig. 5).

Discussion

Global food and animal feed demand has been predicted to grow more than 50% over the next three decades27. This growth must occur on current crop-lands to avoid deforestation and other land-use changes that release additional CO2 to the atmosphere. We find that modelled crop-land NCS provide crop co-benefits in some, but far from all, circumstances. Adopting crop-land NCS can boost crop yields, albeit at a far lower climate benefit when balancing mitigation with the need for higher crop production for food and feed.

Previous assessments largely excluded soil N2O, future climate change and other dimensions of food production such as yield1,10,11,12,13,16,28. By including these components, our estimates of GHG mitigation potential from cover crops and no tillage are considerably lower than some other previous studies, which include estimates of crop-land GHG mitigation as high as 7 Pg CO2-eq yr−1 (refs. 16,29), whereas more recent estimates focused on individual or combined practices place the potential at 1.0–2.5 Pg CO2-eq yr−1 (refs. 11,12,13). Our near-term cumulative estimate of 35.6 Pg CO2-eq (1.0 Pg CO2-eq yr−1, 95% CI (0.94, 1.1)) based on a goal of maximizing GHG mitigation (ignoring crop yield impacts) is within the lower end of this range; however, our estimate based on balanced GHG mitigation and crop yield benefits is substantially lower. Regardless, direct comparisons should be interpreted cautiously because of differences in estimation methods, assumptions around practice adoption rates, cover crop types and applicable crop-land area in previous assessments.

There is appreciable uncertainty in our modelled GHG mitigation and crop yield estimates. Similar to other recent DayCent studies, grid-level GHG uncertainty exceeded 100% in many areas30,31. This uncertainty was still large at regional and global scales (reported as a 95% CI), but we were able to detect a clearer signal at these aggregate scales from NCS practices. Model uncertainty is large because of variability in experimental site data that is fully captured by DayCent30,32. We also found some evidence for a synergistic SOC effect (that is, more than additive) of combining residue retention, no tillage and cover crops for which there is limited empirical evidence and needs further investigation23. Further, the model has not been validated across all the geographies included in this study due to limited research, particularly in developing countries. Long-term benchmark datasets, of which there are few, of SOC, N2O and crop yield response to individual and combined practices are a critical need for model improvement and uncertainty reduction. In future work, multi-model ensembles—still uncommon in this field—could produce more precise estimates although this approach may not produce results more robust than single models, especially in the absence of large-scale empirical model calibration efforts33.

Crop-land NCS as an emissions reduction and carbon dioxide removal strategy presents additional risks. Newly sequestered soil C from crop-land NCS is vulnerable to re-release back into the atmosphere if management subsequently reverts to less sustainable practices. Recent work indicates that CO2 storage of less than 1,000 years is inadequate for negating fossil fuel emissions34, and the fate of SOC storage over these extended timescales is impossible to predict with confidence. Crop-land NCS with less long-term durability can still support land-based emissions reductions targets and build back the soil carbon debt35,36,37,38 in the shorter term. However, it is important to recognize that this is a removal that would need to be continually managed rather than an inherently durable form of sequestration39.

Yield benefits from cover cropping with no tillage were more consistent than GHG mitigation outcomes over the next several decades. This points to a clearer opportunity to address growing food and animal feed demand with these practices over a carbon-first agenda40. We found only modest GHG mitigation benefits—cumulative near-term mitigation (35 years) amounted to less than 10% of all annual GHG emissions in 202341—after accounting for soil N2O and crop production impacts. Hence, better soil management will have larger benefits for food production and only constitute a fraction of food system decarbonization; reaching climate goals in the food system will entail closer scrutiny of GHG-intensive foods.

Methods

DayCent model

We used the DayCent v. 380 ecosystem model to simulate future crop yields, SOC to a depth of 0.3 m and soil nitrogen dynamics to the bottom of the soil profile in maize, soybean and spring wheat crop-lands. The Daily Century model, DayCent, simulates the dynamics and flows of carbon, nitrogen, phosphorus and sulfur between soils, vegetation and the atmosphere at a daily time step. For this study we only included the elemental flows of carbon and nitrogen. The model requires daily weather, soil physical properties, selection of crop type and cultivar and crop-land management information as input data. DayCent estimates soil carbon and nitrogen balances, trace gas emissions, plant productivity and soil water balances in terrestrial ecosystems42.

Here we simulate soil C dynamics to a depth of 0.3 m and water and nitrogen flows to the bottom of the soil profile. The soil C submodel conceptualizes SOC turnover in three separate pools: active, slow and passive43. Microbial processes and products are implicitly represented in the model. In the active pool SOC turnover time is months to years, and it contains more easily metabolized plant materials and soil microbes. The slow pool contains more chemically complex plant material and microbial products with a turnover time of decades. Finally, the passive pool represents physically and chemically stabilized SOC with centuries-long turnover times. Climate variables and soil properties influence the decomposition rates of all three pools, and physical disturbance, particularly by tillage, impacts decomposition of the active and passive pools. Soil texture, that is, clay and sand content, affects C transfer between pools.

Recent improvements to the DayCent model include its plant production44 and soil organic matter modules43 and regionalized crop parameters45. The plant production module better simulates plant canopy production using a green leaf area index based on growing degree days. It also incorporates the evapotranspiration calculation recommended by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO)42,44,46. A Bayesian calibration method applying the sampling importance resampling was used to parameterize the soil organic matter module using a global long-term dataset reducing model uncertainty for predicting soil organic carbon stocks43. This Bayesian framework was recently applied to improve maize crop production parameters resulting in regional crop types that better agreed with crop production data relative to a single maize type45. This same approach was applied to soybean and spring wheat crops for this study. Additional details about the recent calibration and validation of DayCent are discussed in Supplementary Methods.

Geospatial input datasets

DayCent simulations were completed at a 0.5° × 0.5° spatial resolution (approximately 55.5 km at the Equator). The required grid-specific input variables included daily maximum and minimum temperatures; precipitation; soil properties; historic and current land use; management practices including cultivation, planting and harvest; nitrogen inputs (manure and fertilizer); irrigation and tillage43. Climate input data for simulations came from daily downscaled Climate Model Intercomparison Project (CMIP6) climate data for Shared Socioeconomic Pathway (SSP) 3–7.0. We chose not to model SSP5–8.5 because it is no longer considered a plausible future climate scenario given current GHG mitigation commitments by governments leaving SSP3–7.0 as an upper-end estimate47. However, we note the assumptions about future aerosols in SSP3–7.0 used for CMIP6 limit its utility as an upper-end future climate scenario48.

We included 24 global climate models (GCMs) as SSP3–7.0 climate variants in our simulations (Supplementary Table 2); data were obtained from Thrasher et al.49. More information about this dataset and how it was used as input into DayCent is available in Supplementary Methods. Annual atmospheric CO2 concentrations over the simulation period, 2016–2100, for SSP3–7.0 were from Meinshausen et al.50. Our SSP3–7.0 climate variants included ‘hot’ models classified by Hausfather et al.51 in the Sixth Assessment report by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC AR6).

Data on crop-land extent for the three crop types (maize, soybean and spring wheat) and water management (rain-fed or irrigated) were from ISMIP52 and soil data from the Harmonized World Soil Database53. Crop-land management information for planting and harvest dates are based on Sacks et al.54 and nitrogen and manure inputs from Jägermeyr et al.55. Because we used a growing degree day version of DayCent, exact crop harvest dates varied slightly from Sacks et al.54. The crop calendars were applied to both rain-fed and irrigated cropping systems because of a lack of disaggregated calendars for irrigated cropping systems. To derive carbon content of manure inputs, we used information about livestock species56 and manure C:N ratios57,58. The fraction of mineral nitrogen fertilizer from ammonium, nitrate and urea was estimated at the national-level from International Fertilizer Association (IFA)59. Because we lacked information about irrigation scheduling, model simulations were run allowing DayCent to apply water up to field capacity through irrigation events whenever soil water fell below 92.5% over the growing season. The proportion of crop residue returned to the soil at time of harvest was determined by country-level estimates for cereal crops from Wirsenius60 and Wirsenius et al.61. We used the crop type ‘cultivars’ developed in Yang et al.45 for maize and applied the same methodology for soybean and wheat. Crop-specific tillage management was from Porwollik et al.62.

Model simulations

The model simulation design included three stages: spin-up, historical baseline and future management with or without crop-land NCS. First, there was a model spin-up period to allow SOC stocks to reach equilibrium with historical climate and soil characteristics. The spin-up period lasted approximately 10,000 years under native vegetation63. For the historical baseline, crops were simulated as continuous rain-fed or irrigated monocultures because of expected GHG emissions differences with water management starting in 1700 or the year of initial cultivation in regions with expanding agricultural production64,65,66. The exact year of agricultural land conversion varied by grid cell and the land conversion year corresponded to the first year with a majority or more of the final crop-land area in 2015. Tillage, fertilization, crop residue return and model crop ‘cultivars’ varied over this period according to historical management from the geospatial datasets described above. Second, we simulated the historical baseline crop-land management period (1700–2015) to approximate initial C and N pools at the start of the future simulation (Supplementary Methods). Finally, we explored future crop-land management through either continued management or the global adoption of crop-land NCS (2016–2100). For crop-land NCS we assumed immediate adoption over the full crop-land area to assess the technical potential consistent with other studies. We did not include expansion or contraction of crop-land area in this analysis.

We simulated five management scenarios in the future period: (1) continued crop-land management under current, conventional practices, (2) grass cover crop with conventional tillage, (3) legume cover crop with conventional tillage, (4) grass cover crop with no tillage and (5) legume cover crop with no tillage. Continued management (scenario 1) includes tillage and residue retention as described above; cover crops and no tillage were not included in this scenario. Crop residue return rates were maintained at the country-level estimates60,61 for the continued management scenario. For the crop-land NCS scenarios (scenarios 2–4), all crop residue was returned to the soil at harvest for a 100% residue retention rate.

Both the legume and grass cover crop were simulated during the fallow period between the main crop harvest and planting dates. Because of the short fallow period between winter wheat crop harvest and planting the following fall, we excluded cover cropping in this cropping system and only included cover crops in spring wheat. Rye was selected to represent the grass cover crop whereas clover was simulated as the legume cover crop. The parameter values for these crops are based on the calibration described in McClelland et al.67. We selected these specific cultivars as functional type representatives because they are informed by the highest number of field observations. Cover crops were planted one week after the main crop harvest and terminated with an herbicide event two weeks before main crop planting. We simulated cover crops on more than 405 million hectares of crop-land.

Nitrogen inputs were unchanged in the five management scenarios. Reducing N inputs even when a legume cover crop is added to a crop rotation is still rarely practised68,69. In a national survey of US growers that adopted cover crops, most reported no N fertilizer savings70. Realizing the potential for reducing N fertilization with cover crops may also take several years to allow for a build-up of soil available N, although this may be more achievable in fields that practise both legume cover cropping with no tillage71,72. It will be important to establish recommended N fertilizer rates to support the reduction of N inputs that minimize N2O emissions without compromising crop yields over time; however, global datasets of recommended N fertilizer rates are lacking. Irrigation scheduling was unchanged but because it is a dynamic estimate in the model based on soil water content, total irrigation water applied varied between scenarios.

Uncertainty estimation

The variation in crop yield responses were estimated from the DayCent simulations for each of the 24 GCM climate variants for SSP3–7.0. To estimate DayCent model GHG emissions uncertainty, we applied a Monte Carlo approach as described in Ogle et al.32 and more recently in Ogle et al.30. Uncertainty associated with errors in model structure and parameters for soil organic carbon stocks and direct N2O emissions were approximated through an empirical method with a linear mixed-effect model. The linear mixed-effect model estimates ‘true’ soil organic carbon stocks or direct N2O fluxes from long-term experimental data as a function of the predicted DayCent stocks or fluxes and other covariates to address bias in DayCent predictions30,73. Random effects for site and year were not included in the uncertainty analysis.

Indirect N2O flux uncertainty associated with volatilized and leached nitrogen was also analysed with a Monte Carlo approach. Indirect N2O emissions, leached and volatilized N, were estimated according to the 2019 Refinement to the 2006 IPCC Guidelines for National Greenhouse Gas Inventories74,75. We applied the disaggregated Tier 1 emission factors (EF) by climate (wet or dry) from Table 11.3 to calculate indirect N2O emission associated with N volatilization and redeposition (EF4) whereas indirect N2O emissions from inorganic and organic N leaching were estimated using EF575.

The Monte Carlo analysis was conducted with 500 iterations to propagate error from the model structural and Tier 1 sources. For each iteration we randomly selected one of the climate variants from the 24 GCMs. Soil organic carbon stocks and direct N2O emissions for each iteration were estimated by a random selection of parameter values from the empirical estimator for each grid cell, crop type (maize, soybean, spring wheat), irrigation management (rain-fed or irrigated) and management scenario. Indirect N2O emissions for volatilization and leaching were estimated for each iteration by a random selection of EF values from a truncated normal distribution based on the standard deviation for EF4 and EF574,75.

Because of failed runs or missing geospatial input data, some grid cells containing a small amount of crop-land area were missing from our simulations. We imputed these missing values with uncertainty to generate regional and global estimates over all eligible crop-land areas in this study (~405 million hectares). These imputed values were not used in analyses of hectare-level responses or for the explainable machine learning. Missing values were imputed by a Monte Carlo approach with 500 iterations for GHG difference estimates and 24 iterations (representing the climate variants) for yield difference estimates. A random value for each iteration was selected from a normal distribution of GHG or yield estimates by region for each crop type, irrigation management and management scenario. We grouped regions according to the IPCC classification used in Roe et al.13: Asia and developing Pacific (ADP); Africa and Middle East (AME); developed (DEV); East Europe and West–Central Asia (EEWCA) and Latin America and Caribbean (LAC).

Soil carbon, direct N2O, indirect N2O emissions and yields were estimated for each iteration, grid cell, crop type, irrigation management and scenario from 2016 to 2100. GHG estimates are the sum of soil carbon storage, direct N2O and indirect N2O emissions (converted to CO2 equivalents) for each year, and GHG mitigation potential for each scenario is the difference between estimates for the crop-land NCS scenario and the continued, conventional practices scenario. Positive GHG values for a crop-land NCS scenario reflect GHG mitigation (or lower emissions) whereas negative values represent higher GHG emissions relative to continued management. Crop yield differences similarly reflect higher or lower crop yields for a crop-land NCS scenario relative to continued management.

We reported data for two time periods, 2016–2050 and 2016–2100, which we refer to as the near term and medium term, respectively. Because of annual variability in GHG and yield responses, annual estimates are reported by dividing the cumulative responses by the number of years since the start of simulation over the time period of interest: 35 (near term) or 85 years (medium term). Reported GHG mitigation estimates are the mean and standard error of the Monte Carlo analysis and yield estimates the mean and standard error of climate variant simulations. Global and regional estimates for each scenario were calculated according to the following equations:

where d is the response variable, h is the number of hectares, r is the region, c is the crop type, m is the irrigation management and g is the grid cell. For equation (3), N is the independent sample size, which we treated as 24 for the number of unique climate variants. These estimates were then used to calculate the 95% confidence interval.

Hectare-level GHG and yield potential estimates are based on crop-area-weighted means and weighted standard deviations and standard error. Weights were calculated as the proportion of hectares for each crop and irrigation management type in a grid cell, giving more weight to responses with a larger share of crop-land area.

Finally, we estimated maximum global and regional GHG mitigation and yield potential based on four possible goals: (1) maximum GHG mitigation potential (ignoring yield impacts), (2) maximum yield potential (ignoring GHG impacts), (3) maximum GHG mitigation potential restricted to scenarios that do not reduce crop yields and (4) maximum yield potential restricted to scenarios that do not increase GHG emissions. Goals 3 and 4 are considered sustainable, and they identify the Pareto-optimal solution (or scenario) whereby GHG mitigation (or crop yield) does not worsen the outcome of the other, that is, crop yield losses or GHG emissions. For each grid cell, crop type and irrigation level, a GHG and yield difference estimate was selected for a single scenario according to the following:

-

1.

Maximum GHG mitigation potential (ignoring yield impacts). For each grid cell, crop and irrigation management type, we selected the scenario that most frequently had the maximum GHG mitigation potential across all Monte Carlo iterations. If GHG was negative, indicating higher emissions, continued management was selected resulting in no change in GHG or yield.

-

2.

Maximum yield potential (ignoring GHG impacts). For each grid cell, crop and irrigation management type, we selected the scenario that most frequently had the maximum yield potential across all climate variants. If yield was negative, indicating lower crop yields, continued management was selected resulting in no change in yield or GHG emissions.

-

3.

Maximum GHG mitigation potential restricted to scenarios that do not reduce crop yields. For each grid cell, crop and irrigation management type, we first constrained available scenarios to ones that resulted in no crop yield differences or higher crop yields across the climate variants. If all scenarios led to lower crop yields, continued management was selected. We then selected from the remaining available scenarios the one that most frequently had the maximum GHG mitigation potential across all Monte Carlo iterations. Again, if GHG was negative, indicating higher emissions, continued management was selected resulting in no change in GHG or yield.

-

4.

Maximum yield potential restricted to scenarios that do not increase GHG emissions. For each grid cell, crop and irrigation management type, we first constrained available scenarios to ones that resulted in no GHG differences or GHG mitigation across the Monte Carlo iterations. If all scenarios led to higher GHG, continued management was selected. We then selected from the remaining available scenarios the one that most frequently had the maximum yield potential across all climate variants. Again, if yield was negative, indicating lower crop yields, continued management was selected resulting in no change in yield or GHG emissions.

Goal-based global and regional estimates were then calculated according to equations (1)–(3). A complete workflow of the uncertainty assessment applied in this study is provided in Supplementary Fig. 8.

Explainable machine learning

Explainable machine learning using SHapley Additive exPlanation (SHAP) values76 was performed to assess how climate, site and management variables contributed to modelled differences in GHG emissions and crop yields between the NCS scenarios and the continued crop-land management scenario. SHAP values were estimated using the R package fastshap (version 0.1.0)77 from random forest models using ranger (version 0.14.1)78. The target variable was one of four classes estimated from the mean cumulative end-of-century GHG emissions and yield differences from the Monte Carlo analysis: both favourable (GHG mitigation and higher yields), mitigation-favourable (GHG mitigation and lower yields), yield-favourable (GHG emissions and higher yields) and both unfavourable (GHG emissions and lower yields). Features in the random forest models were both categorical and continuous including bioclimatic variables, which were the mean response across all 24 GCM climate variants for SSP3–7.0, site variables including initial soil C stocks and soil texture and management variables such as N inputs and initial residue retention rates.

We evaluated random forest model performance with the Out-of-Bag prediction error; prediction error is the percentage of misclassified samples in Out-of-Bag sample (Supplementary Table 1). Random forest models were run with default parameters at 500 trees, mtry of 4 and node size of 10, and models included 24 features. We removed extreme outliers in two features, initial soil mineral nitrogen and soil nitrate stocks, using a cut-off of values <1% and >99% percentiles. Highly correlated features were removed from the dataset before creating the random forest models. SHAP values were estimated across classes and for each individual class with nsim set to 50 Monte Carlo repetitions.

Data analysis and processing

We used the R programming language to automate DayCent model simulations, the uncertainty analyses, data processing and data analysis (version 4.1.2)79. All geospatial datasets were aggregated to a 0.5° × 0.5° spatial resolution using the terra package (version 1.7-46)80. The high performance cluster at the Cornell University Center for Advanced Computing was used to run all DayCent model simulations.

Combined GHG emissions from SOC and N2O emissions were first converted to CO2 equivalents (CO2-eq) using the 100-year global warming potential (GWP100) values from the IPCC Sixth Assessment Report before summing2. We used a C content of 42% to convert modelled grain yield C into dry matter81.

We applied an one-sided differenced bootstrap significance test to evaluate the mean difference in near-term GHG mitigation between grass cover crops with no tillage and legume cover crops with no tillage. A sample distribution for the mean difference was created by randomly selecting 24 mean differences (representative of the independent sample size) from the Monte Carlo distribution with replacement 1,001 times. Significance was evaluated with a one-sided 95% confidence interval.

Data were reprojected to Eckert IV for all map figures. Map figures do not include imputed estimates. Shape files in base maps for all figures use World Bank-approved administrative boundaries82.

Data availability

Geospatial and country-level data used as input for DayCent model simulations are available from the following publicly accessible platforms. Climate input data are available from NEX-GDDP-CMIP6 (https://registry.opendata.aws/nex-gddp-cmip6/). Crop-land extent data are available from ISMIP (https://data.isimip.org/). Soil data are available from the Harmonized World Soil Database v1.2 (https://www.fao.org/soils-portal/data-hub/soil-maps-and-databases/harmonized-world-soil-database-v12/en/). Crop-land management data are available at https://sage.nelson.wisc.edu/data-and-models/datasets/crop-calendar-dataset/. Nitrogen input data are available via Zenodo at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.4954582 (ref. 83). Synthetic nitrogen fertilizer fraction data are available from IFA (https://www.ifastat.org/databases/plant-nutrition). Crop tillage data are available at https://doi.org/10.5880/PIK.2019.009. All other input data for model simulations are described in Methods and available from refs. 50,57,60,61. The initial DayCent model simulation data used for the uncertainty analysis are available via Zenodo at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14914313 (ref. 84). The uncertainty output dataset is available via Zenodo at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15116882 (ref. 85). Data to recreate the analyses and the resulting output are available via Zenodo at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15119896 (ref. 86).

Code availability

A publicly accessible version of the DayCent model can be found at https://www.soilcarbonsolutionscenter.com/daycent. Access to the version of the DayCent model used in this study is available upon request to S.M.O. (Colorado State University). Code to recreate the analyses from this study is available via Zenodo at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14907983 (ref. 87).

References

Griscom, B. W. et al. Natural climate solutions. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 114, 11645–11650 (2017).

Calvin, K. et al. in Climate Change 2023: Synthesis Report (eds Lee, H. & Romero, J.) (IPCC, 2023); https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/syr/

Buma, B. et al. Expert review of the science underlying nature-based climate solutions. Nat. Clim. Change 14, 402–406 (2024).

Ellis, P. W. et al. The principles of natural climate solutions. Nat. Commun. 15, 547 (2024).

Tamburini, G. et al. Agricultural diversification promotes multiple ecosystem services without compromising yield. Sci. Adv. 6, eaba1715 (2020).

Quemada, M., Lassaletta, L., Leip, A., Jones, A. & Lugato, E. Integrated management for sustainable cropping systems: looking beyond the greenhouse balance at the field scale. Glob. Change Biol. 26, 2584–2598 (2020).

Abdalla, M. et al. A critical review of the impacts of cover crops on nitrogen leaching, net greenhouse gas balance and crop productivity. Glob. Change Biol. 25, 2530–2543 (2019).

Vendig, I. et al. Quantifying direct yield benefits of soil carbon increases from cover cropping. Nat. Sustain 6, 1125–1134 (2023).

Deines, J. M. et al. Recent cover crop adoption is associated with small maize and soybean yield losses in the United States. Glob. Change Biol. 29, 794–807 (2023).

Bossio, D. A. et al. The role of soil carbon in natural climate solutions. Nat. Sustain 3, 391–398 (2020).

Almaraz, M. et al. Soil carbon sequestration in global working lands as a gateway for negative emission technologies. Glob. Change Biol. 29, 5988–5998 (2023).

Lessmann, M., Ros, G. H., Young, M. D. & de Vries, W. Global variation in soil carbon sequestration potential through improved cropland management. Glob. Change Biol. 28, 1162–1177 (2022).

Roe, S. et al. Land-based measures to mitigate climate change: potential and feasibility by country. Glob. Change Biol. 27, 6025–6058 (2021).

Walker, W. S. et al. The global potential for increased storage of carbon on land. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 119, e2111312119 (2022).

Beillouin, D. et al. A global meta-analysis of soil organic carbon in the Anthropocene. Nat. Commun. 14, 3700 (2023).

Zomer, R. J., Bossio, D. A., Sommer, R. & Verchot, L. V. Global sequestration potential of increased organic carbon in cropland soils. Sci. Rep. 7, 15554 (2017).

Lugato, E., Leip, A. & Jones, A. Mitigation potential of soil carbon management overestimated by neglecting N2O emissions. Nat. Clim. Change 8, 219–223 (2018).

Guenet, B. et al. Can N2O emissions offset the benefits from soil organic carbon storage? Glob. Change Biol. 27, 237–256 (2021).

McClelland, S. C., Paustian, K. & Schipanski, M. E. Management of cover crops in temperate climates influences soil organic carbon stocks: a meta-analysis. Ecol. Appl. 31, e02278 (2021).

Poeplau, C. & Don, A. Carbon sequestration in agricultural soils via cultivation of cover crops—a meta-analysis. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 200, 33–41 (2015).

Nouri, A., Lukas, S., Singh, S., Singh, S. & Machado, S. When do cover crops reduce nitrate leaching? A global meta-analysis. Glob. Change Biol. 28, 4736–4749 (2022).

Basche, A. D., Miguez, F. E., Kaspar, T. C. & Castellano, M. J. Do cover crops increase or decrease nitrous oxide emissions? A meta-analysis. J. Soil Water Conserv. 69, 471–482 (2014).

Bai, X. et al. Responses of soil carbon sequestration to climate-smart agriculture practices: a meta-analysis. Glob. Change Biol. 25, 2591–2606 (2019).

Smith, P. et al. Climate Change and Land: IPCC Special Report on Climate Change, Desertification, Land Degradation, Sustainable Land Management, Food Security, and Greenhouse Gas Fluxes in Terrestrial Ecosystems (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2022); https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009157988

Marvin, D. C., Sleeter, B. M., Cameron, D. R., Nelson, E. & Plantinga, A. J. Natural climate solutions provide robust carbon mitigation capacity under future climate change scenarios. Sci. Rep. 13, 19008 (2023).

Amundson, R. & Biardeau, L. Soil carbon sequestration is an elusive climate mitigation tool. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 115, 11652–11656 (2018).

Falcon, W. P., Naylor, R. L. & Shankar, N. D. Rethinking global food demand for 2050. Popul. Dev. Rev. 48, 921–957 (2022).

Jian, J., Du, X., Reiter, M. S. & Stewart, R. D. A meta-analysis of global cropland soil carbon changes due to cover cropping. Soil Biol. Biochem. 143, 107735 (2020).

Fuss, S. et al. Negative emissions—Part 2: Costs, potentials and side effects. Environ. Res. Lett. 13, 063002 (2018).

Ogle, S. M. et al. Counterfactual scenarios reveal historical impact of cropland management on soil organic carbon stocks in the United States. Sci. Rep. 13, 14564 (2023).

Eash, L., Ogle, S., McClelland, S. C., Fonte, S. J. & Schipanski, M. E. Climate mitigation potential of cover crops in the United States is regionally concentrated and lower than previous estimates. Glob. Change Biol. 30, e17372 (2024).

Ogle, S. M. et al. Scale and uncertainty in modeled soil organic carbon stock changes for US croplands using a process-based model. Glob. Change Biol. 16, 810–822 (2010).

Sándor, R. et al. Ensemble modelling of carbon fluxes in grasslands and croplands. Field Crops Res. 252, 107791 (2020).

Brunner, C., Hausfather, Z. & Knutti, R. Durability of carbon dioxide removal is critical for Paris climate goals. Commun. Earth Environ. 5, 645 (2024).

Sanderman, J., Hengl, T. & Fiske, G. J. Soil carbon debt of 12,000 years of human land use. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 114, 9575–9580 (2017).

Saifuddin, M., Abramoff, R. Z., Foster, E. J. & McClelland, S. C. Soil carbon offset markets are not a just climate solution. Front. Ecol. Environ. 22, e2781 (2024).

Dynarski, K. A., Bossio, D. A. & Scow, K. M. Dynamic stability of soil carbon: reassessing the ‘permanence’ of soil carbon sequestration. Front. Environ. Sci. 8, 514701 (2020).

Mitchell, E. et al. Making soil carbon credits work for climate change mitigation. Carbon Manage. 15, 2430780 (2024).

Janzen, H. H. Russell review soil carbon stewardship: thinking in circles. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 75, e13536 (2024).

Moinet, G. Y. K., Hijbeek, R., van Vuuren, D. P. & Giller, K. E. Carbon for soils, not soils for carbon. Glob. Change Biol. 29, 2384–2398 (2023).

Emissions Gap Report 2024: No More Hot Air … Please! With a Massive Gap Between Rhetoric and Reality, Countries Draft New Climate Commitments (UNEP, 2024).

Zhang, Y. et al. DayCent model predictions of NPP and grain yields for agricultural lands in the contiguous U.S. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosci. 125, e2020JG005750 (2020).

Gurung, R. B., Ogle, S. M., Breidt, F. J., Williams, S. A. & Parton, W. J. Bayesian calibration of the DayCent ecosystem model to simulate soil organic carbon dynamics and reduce model uncertainty. Geoderma 376, 114529 (2020).

Zhang, Y., Suyker, A. & Paustian, K. Improved crop canopy and water balance dynamics for agroecosystem modeling using DayCent. Agron. J. 110, 511–524 (2018).

Yang, Y. et al. Regionalizing crop types to enhance global ecosystem modeling of maize production. Environ. Res. Lett. 17, 014013 (2021).

Allen, R. G. Crop evapotranspiration. FAO Irrig. Drain. Pap. 56, 60–64 (1998).

Shiogama, H. et al. Important distinctiveness of SSP3–7.0 for use in impact assessments. Nat. Clim. Change 13, 1276–1278 (2023).

Lund, M. T., Myhre, G. & Samset, B. H. Anthropogenic aerosol forcing under the shared socioeconomic pathways. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 19, 13827–13839 (2019).

Thrasher, B. et al. NASA global daily downscaled projections, CMIP6. Sci. Data 9, 262 (2022).

Meinshausen, M. et al. The shared socio-economic pathway (SSP) greenhouse gas concentrations and their extensions to 2500. Geosci. Model Dev. 13, 3571–3605 (2020).

Hausfather, Z., Marvel, K., Schmidt, G. A., Nielsen-Gammon, J. W. & Zelinka, M. Climate simulations: recognize the ‘hot model’ problem. Nature 605, 26–29 (2022).

Volkholz, J. & Ostberg, S. ISIMIP3a landuse input data. ISMIP Repository https://data.isimip.org/ (2022).

Harmonized World Soil Database (FAO, IIASA, ISRIC, ISS-CAS & JRC, 2009); https://www.fao.org/soils-portal/data-hub/soil-maps-and-databases/harmonized-world-soil-database-v12/en/

Sacks, W. J., Deryng, D., Foley, J. A. & Ramankutty, N. Crop planting dates: an analysis of global patterns. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 19, 607–620 (2010).

Jägermeyr, J. et al. Climate impacts on global agriculture emerge earlier in new generation of climate and crop models. Nat. Food 2, 873–885 (2021).

GLW4: Gridded Livestock of the World (FAO, 2023); https://www.fao.org/livestock-systems/global-distributions/en/

Devault, M., Woolf, D. & Lehmann, J. Nutrient recycling potential of excreta for global crop and grassland production. Nat. Sustain. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-024-01467-8 (2024).

Phyllis2: Database for Biomass and Waste (UKERC, 2023); https://phyllis.nl/

IFASTAT (IFA, 2023); https://www.ifastat.org/databases/plant-nutrition

Wirsenius, S. Human Use of Land and Organic Materials (Chalmers Univ. of Technology, 2000).

Wirsenius, S. The biomass metabolism of the food system: a model-based survey of the global and regional turnover of food biomass. J. Ind. Ecol. 7, 47–80 (2003).

Porwollik, V., Rolinski, S., Heinke, J. & Müller, C. Generating a rule-based global gridded tillage dataset. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 11, 823–843 (2019).

Cramer, W. et al. Comparing global models of terrestrial net primary productivity (NPP): overview and key results. Glob. Change Biol. 5, 1–15 (1999).

Aguilera, E. et al. Methane emissions from artificial waterbodies dominate the carbon footprint of irrigation: a study of transitions in the food–energy–water–climate nexus (Spain, 1900–2014). Environ. Sci. Technol. 53, 5091–5101 (2019).

Driscoll, A. W., Conant, R. T., Marston, L. T., Choi, E. & Mueller, N. D. Greenhouse gas emissions from US irrigation pumping and implications for climate-smart irrigation policy. Nat. Commun. 15, 675 (2024).

Qin, J. et al. Global energy use and carbon emissions from irrigated agriculture. Nat. Commun. 15, 3084 (2024).

McClelland, S. C., Paustian, K., Williams, S. & Schipanski, M. E. Modeling cover crop biomass production and related emissions to improve farm-scale decision-support tools. Agric. Syst. 191, 103151 (2021).

Wittwer, R. A. & van der Heijden, M. G. A. Cover crops as a tool to reduce reliance on intensive tillage and nitrogen fertilization in conventional arable cropping systems. Field Crops Res. 249, 107736 (2020).

Tonitto, C., David, M. B. & Drinkwater, L. E. Replacing bare fallows with cover crops in fertilizer-intensive cropping systems: a meta-analysis of crop yield and N dynamics. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 112, 58–72 (2006).

National Cover Crop Survey Report 2022–2023 (Conservation Technology Information Center, 2023); https://www.ctic.org/data/Cover_Crops_Research_and_Demonstration_Cover_Crop_Survey

Douxchamps, S. et al. Nitrogen balances in farmers fields under alternative uses of a cover crop legume: a case study from Nicaragua. Nutr. Cycl. Agroecosyst. 88, 447–462 (2010).

Doane, T. A. et al. Nitrogen supply from fertilizer and legume cover crop in the transition to no-tillage for irrigated row crops. Nutr. Cycl. Agroecosyst. 85, 253–262 (2009).

Ogle, S. M., Breidt, F. J., Easter, M., Williams, S. & Paustian, K. An empirically based approach for estimating uncertainty associated with modelling carbon sequestration in soils. Ecol. Modell. 205, 453–463 (2007).

IPCC 2006 IPCC Guidelines for National Greenhouse Gas Inventories (IGES, 2006).

Refinement to the 2006 IPCC Guidelines for National Greenhouse Gas Inventories (IPCC, 2019).

Lundberg, S. M. et al. From local explanations to global understanding with explainable AI for trees. Nat. Mach. Intell. 2, 56–67 (2020).

Greenwell, B. fastshap: Fast Approximate Shapley Values (2023).

Wright, M. N. & Ziegler, A. ranger: a fast implementation of random forests for high dimensional data in C++ and R. J. Stat. Soft. 77, 1–17 (2017).

R Core Team R: Language and Environment for Statistical Computing 1–17 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2021).

Hijmans, R. J. terra: Spatial Data Analysis (2023).

Ma, S. et al. Variations and determinants of carbon content in plants: a global synthesis. Biogeosciences 15, 693–702 (2018).

World Bank Official Boundaries version 3 (World Bank, 2020); https://datacatalog.worldbank.org/

Heinke, J., Müller, C., Mueller, N. D. & Jägermeyr, J. N application rates from mineral fertiliser and manure. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.4954582 (2021).

McClelland, S. C. & Woolf, D. DayCent model simulation data for ‘managing for climate and production goals on crop-lands’. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14914313 (2025).

McClelland, S. C. & Woolf, D. DayCent model uncertainty data for ‘managing for climate and production goals on crop-lands’. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15116882 (2025).

McClelland, S. C. & Woolf, D. Analysis data for ‘managing for climate and production goals on crop-lands’. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15119896 (2025).

McClelland, S. C. & Woolf, D. scmcclelland/daycent-global-analysis-SSP370: GitHub repository for ‘managing for climate and production goals on croplands’. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14907983 (2025).

Acknowledgements

S.C.M., D.W., J.S., D.R.G., S.A.W. and D.B. were supported by funding from The Nature Conservancy (TNC; S.C.M., D.W., S.A.W., D.B.) or from Environmental Defense Fund (EDF; S.C.M., D.W., J.S., D.R.G.) with awards from the Bezos Earth Fund (TNC and EDF), King Philanthropies (EDF) and Arcadia, a charitable fund of L. Rausing and P. Baldwin (EDF). D.W. received additional funding from the Cornell Institute for Digital Agriculture, Cornell Atkinson Center for Sustainability and AI-CLIMATE (AI Institute for Climate–Land Interactions, Mitigation, Adaptation, Tradeoffs and Economy), funded by the National Institute for Food and Agriculture (NIFA 2023-67021-39829). Funding was also provided by the US Environmental Protection Agency through an interagency agreement to the US Forest Service (18-CR-11242305-109) to support the contribution of S.M.O. and Y.Y. This research was conducted with support from the Cornell University Center for Advanced Computing, which receives funding from Cornell University, the National Science Foundation and members of its partner programme. We also acknowledge support from the Environmental Molecular Sciences Laboratory (EMSL), a DOE Office of Science User Facility at the Pacific Northwest National Laboratory. We thank A. Eagle and N. U. Aragon for their input on earlier aspects of this research and paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.C.M. and D.W. conceived of the study with input from J.S., J.L., D.B. and S.A.W. S.C.M. and D.W. developed the modelling protocol. Y.Y. and S.M.O. provided the gridded historical baseline crop-land data. S.C.M. conducted the simulations and led the uncertainty and data analysis with input from D.W. and S.M.O. S.C.M. wrote the first draft of the paper and all authors contributed to editing and revisions.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Climate Change thanks Weili Duan, Shaopeng Wang and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Extended Data Fig. 1 Modeled mean medium-term (2016-2100) annual greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and yield differences for cropland natural climate solutions (NCS) relative to continued management practices.

Left column: GHG; right column: yield. Panels are Grass CC (a,b), Grass CC + Ntill (c,d), Legume CC (e,f), and Legume CC + Ntill (g,h). Scenario: cover crop (CC); and, no-tillage (Ntill). Base map data in a–h from The World Bank under a Creative Commons license CC BY 4.0.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Spatially-explicit tradeoff of near-term (2016–2050) annual greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and yield differences for cropland natural climate solutions (NCS) relative to continued management practices.

Colors indicate lower, no difference, or higher yields and emissions, no difference, or GHG mitigation. For quantitative results, see Fig. 2. Panels are Grass CC (a,), Grass CC + Ntill (b), Legume CC (c), and Legume CC + Ntill (d). Scenario: cover crop (CC); and, no-tillage (Ntill). Base map data in a–d from The World Bank under a Creative Commons license CC BY 4.0.

Extended Data Fig. 3 Spatially-explicit tradeoff of medium-term (2016-2100) annual greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and yield differences for cropland natural climate solutions (NCS) relative to continued management practices.

Colors indicate lower, no difference, or higher yields and emissions, no difference, or GHG mitigation. For quantitative results, see Extended Data Fig. 1. Panels are Grass CC (a,), Grass CC + Ntill (b), Legume CC (c), and Legume CC + Ntill (d). Scenario: cover crop (CC); and, no-tillage (Ntill). Base map data in a–d from The World Bank under a Creative Commons license CC BY 4.0.

Extended Data Fig. 4 Global maximum and balanced goal outcomes for greenhouse gas (GHG) mitigation potential (Pg CO2-eq yr−1; x-axis) by annual yield difference (Pg yr−1; y-axis) for cropland natural climate solutions (NCS) relative to continued management.

Data are presented as mean values with uncertainty (± SEM) for near-term (a) and medium-term (b); horizontal and vertical bars are annual GHG mitigation and yield uncertainty, respectively (n = 24).

Extended Data Fig. 5 Regional practice recommendations for maximizing crop yield benefits while balancing greenhouse gas (GHG) mitigation potential.

Data are presented as mean annual values with 95% CI for the near-term, 2016–2050, and medium-term, 2016–2100 (n = 24). Positive values indicate GHG mitigation or higher yields while negative values indicate GHG emissions or lower yields relative to continued management practices. Scenario: cover crop (CC); and, no-tillage (Ntill). Base map data from The World Bank under a Creative Commons license CC BY 4.0.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Methods, Figs. 1–8, Tables 1 and 2, and References.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

McClelland, S.C., Bossio, D., Gordon, D.R. et al. Managing for climate and production goals on crop-lands. Nat. Clim. Chang. 15, 642–649 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-025-02337-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-025-02337-7