Abstract

Phytoplankton are critical to the Antarctic marine food web and associated biological carbon pump, yet long-term shifts in their community composition are poorly understood. Here, using a machine learning framework and combining pigment samples and environmental samples from austral summertime 1997–2023, we show declines in diatoms and increases in haptophytes and cryptophytes across much of Antarctica’s continental shelf. These trends—which are linked to sea ice increases—reversed after 2016, with a rebound in diatoms and a large increase in cryptophytes, coinciding with the loss of sea ice. Significant changes (P < 0.05) across the 25-year dataset include diatom chlorophyll a (chl-a) declines of 0.32 mg chl-a m−3 (~33% of the climatology) and increases for haptophytes and cryptophytes of 0.08 and 0.23 mg chl-a m−3, respectively. The long-term shifts in phytoplankton assemblages could reduce the dominance of the krill-centric food web and diminish the biologically mediated export of carbon to depth, with implications for the global-ocean carbon sink.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Measuring taxonomic shifts of the Antarctic phytoplankton community in response to climate change is crucial for understanding broader changes in global marine ecosystems and carbon cycling. As the foundation of Antarctic marine ecosystems, phytoplankton support higher trophic levels and drive the biological carbon pump (BCP), leading to carbon export and sequestration1. However, certain phytoplankton taxa make a greater contribution to these pathways than others. In particular, diatoms are the preferred prey for Antarctic krill (Euphausia superba), a species of zooplankton that occupies a key ecological niche in the Southern Ocean (SO)2,3,4, but whose populations have declined over recent decades4 in favour of salps, gelatinous zooplankton with fewer specific trophic links5. Diatoms also contribute disproportionately to carbon export6, in part due to the ballast effect of their dense silica shells. Other groups of smaller phytoplankton, such as haptophytes and cryptophytes, are also present in Antarctic waters, but are more likely to fuel the microbial food web and have lower trophic and carbon export potential.

Climate change affects Antarctic phytoplankton via a multitude of interrelated pathways, including shifts in sea-ice regimes7,8,9 and warming of both the ocean and atmosphere10,11, which influence wind strength, mixed layer depth (MLD)12, nutrient availability and light conditions13,14,15. The impacts of changing these pathways are difficult to anticipate because changes are concurrent and multivariate while responses of phytoplankton and their consumers are complex and differ between taxonomic groups16,17. Nevertheless, several in situ studies investigating the impacts of climate variability on Antarctic phytoplankton have shown the replacement of larger phytoplankton by smaller-celled species and altered bloom phenology18,19,20. Furthermore, these studies have emphasized the complexity of ecological drivers, such as interspecific competition and grazing pressure, in addition to bottom-up forcing (for example, iron and light).

Satellite observations provide insight into large-scale changes in chlorophyll a (chl-a) across the SO, although, ocean-colour observations are limited to summer months at high latitudes as a result of sea-ice cover and low solar elevation in other seasons. Still, satellite studies indicate that SO phytoplankton blooms in the austral summer have increased in amplitude but have tended to terminate earlier21. Furthermore, satellite-based studies have shown that chl-a concentrations in the SO are generally increasing22,23, similar to the climate-driven trends observed recently in low-latitude regions24. However, assessing long-term taxonomic shifts within phytoplankton communities has not been possible on a regional scale, as satellite monitoring only determines total chl-a concentrations and cannot determine taxonomic make-up.

Expanding in situ observations to broader spatial and temporal scales is essential for understanding the response of the circumpolar system to climate change. In this study, we quantify taxonomic shifts in Antarctic phytoplankton using the largest existing database of in situ pigment samples (n = 14,824) ever assembled for the SO25. We analysed this in situ dataset using random-forest models, explanatory data from satellites and data-constrained ocean biogeochemistry models26 to provide insight into the space–time variability of phytoplankton community composition across the high latitudes of the SO. The abundance and trends of key phytoplankton taxa were then mapped for the summer period (December–February) during 1997–2023. Our findings reveal large shifts in key phytoplankton groups alongside changes in total chl-a, which may have critical implications for Antarctic ecosystems and SO carbon cycling.

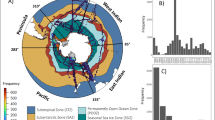

We focus this analysis on: (1) the region encompassing the Antarctic continental shelf (hereafter ‘Antarctic Shelf’) which has the highest chl‑a (1.3 mg chl-a m−3) climatological average (average value across the region throughout all summers in the time series), reflecting its high productivity; and (2) the seasonal sea-ice zone (SSIZ), the area of maximum sea-ice extent). These regions support the iconic Antarctic ecosystems that are likely to be affected by climate change, as demonstrated by sea‐ice loss in the SSIZ8 and regional warming10,11.

Trends in Antarctic chl-a

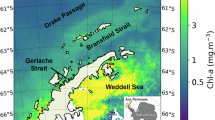

Between 1997 and 2023, summer total chl-a concentrations increased across the combined Antarctic Shelf and SSIZ by 41% (confidence interval (CI) 39–42%; Supplementary Fig. 1), relative to a climatological value of 0.78 mg chl-a m−3 (Fig. 1). This significant increase was confirmed for 80% of locations at the 95% confidence level in autocorrelation-corrected Mann–Kendall tests (Methods). However, there was no zonally averaged trend in the Antarctic Shelf itself (<0.001 mg chl-a m−3 decade−1).

Chlorophyll data are from the European Space Agency ocean-colour climate change initiative project (OC-CCI) product. a, Map showing decadal chl-a trends (Sen slope; Methods) during summer. b, Monthly-mean chl-a anomalies during summer. c, Annual-mean chl-a anomalies. The red lines in b and c represent the trends calculated using the locally estimated scatterplot smoothing (LOESS) approach. Shapefiles for the Antarctic Shelf Break in a from ref. 63 under a CC-BY 3.0 license.

Highly productive shelf regions2,27, such as Prydz Bay and the Ross Sea, which are characterized by large summertime polynyas and ice shelves, experienced large declines in chl-a, in some areas by more than −0.05 mg chl-a m−3 yr−1, highlighting the zonal asymmetry between the Antarctic Shelf and SSIZ (Fig. 1a).

Variations in chl‐a are often used as proxies for shifts in carbon biomass; however, this relationship may vary with physiological status. Phytoplankton adjust their chl‐a to carbon ratios in response to temperature, light and nutrients28,29,30, and particularly iron in the SO31,32. While specific photoacclimation strategies and chl-a to carbon may differ, the overall direction of the response tends to be consistent across taxonomic groups33. For instance, others34 have reported no significant differences in per‐cell chl‐a amounts between diatoms (Fragilariopsis cylindrus) and haptophytes (Phaeocystis antarctica) under similar irradiance conditions. Therefore, despite large phenotypic plasticity between different species, the chl‐a trends shown in Fig. 1 would be coincident with meaningful shifts in biomass or community composition, in response to changing environmental pressures.

To understand changes in phytoplankton communities across the SO, we expanded on previous analyses of a large in situ pigment dateset created using the phytoclass software35. Unlike satellite-derived chl-a, which integrates all phytoplankton into a single bulk measure, in situ pigment analysis enables partitioning of chl-a into distinct phytoplankton groups on the basis of their diagnostic accessory pigments. These pigment samples were combined with model- and satellite-derived environmental data to allow extrapolation beyond the original sampling locations. Owing to their ecological importance, we focus on three key Antarctic phytoplankton groups: diatoms, haptophytes and cryptophytes. For each group, we used random-forest regression to estimate the chl-a of the particular phytoplankton group. Each model was created ten times with different random seeds, with the output taken as the ensemble of the ten individual models. Our model-based estimates agreed well with in situ observations (R2 = 0.81–0.92; Table 1; Supplementary Fig. 2; Methods section ‘Modelling phytoplankton groups’), underscoring the accuracy of the model. A tenfold cross-validation (stratified by voyage) provided an unbiased test of model performance on withheld data, thereby exposing and penalizing overfitting (Methods). Model estimates were restricted to the environmental envelope of the training data to avoid extrapolating into areas outside the training ranges for the summer months of 1997–2023.

An analysis of the modelled output for each location in the study region found significant shifts (P < 0.05) in modelled phytoplankton communities, but these were not uniform, either geographically or temporally, as a result of a shift in phytoplankton communities in December 2016 linked to variability in sea-ice concentration (SIC) (Fig. 2). Here, we address the taxonomic make-up of communities and overall trends before considering the observed shifts and the geographical patterns of changes.

a, The proportion of diatoms, haptophytes and cryptophytes (from left to right) as a percentage of the total community chl-a. The blue outline is the Antarctic continental shelf break. b, The geographical trends (Sen slopes) for each group per year expressed in chl-a concentrations. c, The linear trend (of anomalies) of the averaged modelled estimates in the Antarctic Shelf region (pre-2017, n = 58; post-2017, n = 20; d.f. = n − 2). Trends were assessed using two-sided t-tests with Holm correction for multiple comparisons. Reported values are: diatoms P = 0.005 (pre), P = 0.024 (post); haptophytes P = 0.019 (pre), P = 0.62 (post); and cryptophytes P =0.96 (pre), P = 0.011 (post). Anomalies of each phytoplankton group (dots) linear trends (straight line) as well as the moving average (curved line) and the standard deviations (vertical lines) between December, January and February on the Antarctic Shelf are shown. d, Anomalies of SICs (grey dots) linear trends (green line) as well as the moving average (pink line) on the Antarctic Shelf and the correlation (R2) and significance (***) between SIC and each phytoplankton group with corresponding two-sided P values: diatoms P = 0.18 (pre), P = 0.032 (post); haptophytes P = 0.31 (pre), P = 0.53 (post); and cryptophytes P = 0.48 (pre), 0.039 (post). Shapefiles for the Antarctic Shelf Break in a and b from ref. 63 under a CC-BY 3.0 license.

Modelled phytoplankton distributions (climatological averages), based on summertime environmental conditions (Methods), showed that the combined SSIZ and Antarctic Shelf was primarily co-dominated by diatoms (46%) and haptophytes (32%). The proportion of diatoms was usually greater than haptophytes (Fig. 2a), although there were parts of the Ross Sea where the reverse was true, as in previous regional analyses36,37. The highest proportion of cryptophytes was modelled to occur over the West Antarctic Peninsula and in parts of the Bellingshausen Sea, consistent with previously published in situ data19,20.

Over the multidecadal study period, the geographical trends determined from Sen slopes (a non-parametric method to determine slope of a trend) indicated that the modelled chl-a of diatoms decreased significantly (deseasonalized Mann–Kendall P < 0.05) over 80% of the Antarctic Shelf, with a mean decline of −0.011 mg chl-a m−3 yr−1 (CI −0.012 to −0.009) in statistically significant areas. Haptophytes and cryptophytes generally increased in these regions, whereas diatoms decreased over time (Fig. 2b). The rise in haptophytes was less pronounced than the decline in diatoms; with increases of +0.003 mg chl-a m−3 yr−1 (CI 0.002–0.0035) in statistically significant areas (82% of locations). Similarly, cryptophytes increased in the Antarctic Shelf by +0.0088 mg chl-a m−3 yr−1 (CI 0.0085–0.0091) in statistically significant areas (70% of locations).

An apparent regime shift was evident in the trends for taxa in the Antarctic Shelf region which corresponded with a change in the trend of SIC. Between 1997 and December 2016, diatom stocks declined by 0.03 mg chl-a m−3 yr−1 (P < 0.05), while haptophytes increased by 0.031 mg chl-a m−3 yr−1 (P < 0.05) and cryptophytes decreased slightly by 0.01 mg chl-a m−3 yr−1 (P = 0.96) (Fig. 2c). Between December 2016 and 2023, diatom stocks rebounded sharply by 0.09 mg chl-a m−3 yr−1 (P < 0.05), while haptophytes decreased by 0.02 mg chl-a m−3 yr−1 (P = 0.62) and cryptophytes increased sharply by 0.07 mg chl-a m−3 yr−1 (P < 0.05) (Fig. 2c). The timing of the trend shifts in phytoplankton taxa coincided with the beginning of a pronounced reduction in the concentration of Antarctic sea ice8, from late 2016 (Fig. 2d).

Before 2016, haptophytes appeared to be steadily replacing diatoms, yet even after 2016 when diatoms rebounded, their relative proportions (percentage of chl-a) continued to decline (Supplementary Fig. 3) as their chl-a increased. This broadly aligns with end-of-century projections from Earth system models38. The increase in cryptophytes after 2016 mirrored widespread sea-ice loss8,9 and is also consistent with the previously reported emergence of cryptophytes in West Antarctica from in situ data39 (Fig. 2c). After 2016, SIC accounted for 31% of the variance linked to diatom recovery and 21% of the variance associated with increases in cryptophytes (Fig. 2d). These results suggest a net effect of smaller phytoplankton constituting a larger fraction of summer phytoplankton communities than previously in many areas of the Antarctic Shelf.

The modelled trends in the chl-a of phytoplankton groups were not geographically uniform. Our analysis showed that diatom chl-a declined broadly before 2017 in shelf regions (Fig. 3), but after 2017 diatom chl-a increased across much of the region, except in West Antarctica where concentrations continued to decrease. Haptophyte patterns were spatially heterogeneous with slight increases within the shelf before 2017, but trends were highly spatially variable after 2017. While cryptophytes were already increased in West Antarctica before 2017, their increase became more widespread (nearly circumpolar) thereafter, expanding notably in regions such as the coastal Ross Sea, Prydz Bay and West Antarctica.

Environmental controls and long-term environmental change

To further investigate modelled shifts in phytoplankton taxa, we examined the environmental variables and the associated chl-a for each group (Fig. 4) over the study period (1997–2023) and derived the response of each group to these environmental factors using random-forest partial dependence plots (Supplementary Fig. 4) and using Spearman correlation analysis (Fig. 5). These analyses identified co-occurrence patterns and statistical associations rather than necessarily indicating causal relationships. While this approach does not directly assess phytoplankton sensitive to drivers, it provides valuable ecological insights into modelled distribution patterns and potential responses to environmental change. While these results provide linkages to environmental drivers, we note that use of different models results in substantial variability, and thus caution should be used in mechanistic interpretation. We summarize change in the environmental factors since 1997 and the potential implications for phytoplankton ecology.

Over the 26-yr record, iron (Fe) availability declined at the circumpolar scale (Fig. 4), consistent with in situ observations showing that SO phytoplankton have become more Fe stressed40. Diatoms showed a strong relationship with surface-ocean Fe concentrations with highest chl-a associated with high Fe conditions (>0.4 nM l−1), reinforcing their established requirement for high Fe (ref. 41) (Supplementary Fig. 4) and suggesting that observed reduction in Fe availability probably impacts diatoms more than other groups. In contrast, the models suggest that both haptophytes and cryptophytes were more abundant under lower Fe conditions (<0.4 nM l−1), further indicating that diatoms are competitively disadvantaged by iron-depleted conditions. Correlation patterns confirmed these findings: diatoms were positively correlated with Fe across the shelf, whereas haptophytes and cryptophytes were generally negatively correlated, except in the Ross Sea where all groups showed positive correlations with Fe (Fig. 5).

Environmental trend analysis showed that SIC declined throughout most of the Antarctic Shelf and SSIZ (Fig. 4), consistent with recent studies7,8,9. High SIC was closely linked to elevated chl-a for all groups (Supplementary Fig. 4), which indicated that areas with extensive SIC were associated with greater biomass. Our models indicated that diatoms and cryptophytes were especially abundant where SIC exceeded ~75%, while haptophytes peaked around ~50% (Supplementary Fig. 4). Despite this general pattern, correlations varied by region: in West Antarctica, diatom chl-a was positively correlated with SIC, but in other parts of the shelf, correlations were sometimes negative. Haptophytes tended to be positively correlated with SIC in West Antarctica but negatively so in the Ross Sea, whereas cryptophytes were largely negatively correlated with SIC except in the Ross Sea.

Melting sea ice delivers nutrients (including Fe) and an inoculum of sea-ice algae to the upper ocean42,43, and the low-salinity meltwater forms a shallow, stable mixed layer in which diatoms can bloom27,44. However, since 2017, the widespread decline in Antarctic sea ice7,8,9,45 will alter meltwater input and may affect the timing (phenology) and magnitude of sea-ice algae and bloom dynamics. A stable surface mixed layer associated with reduced ice cover, longer growth season and higher, earlier nutrient supply may have promoted faster bloom initiation.

Between 1997 and 2023, trends in MLD were spatially heterogeneous (Fig. 4), with deepening in the Ross Sea and Prydz Bay and shoaling in the Weddell Sea and West Antarctica. Such differences may result from variable freshwater inputs, buoyancy forcing, changes in wind forcing related to the positive southern annular mode and regional warming, each of which may modulate vertical mixing and thus shape phytoplankton ecology20,46. However, the net effect of this shoaling might be moderated by the positive phase of the southern annular mode, which has driven more intense storms and deeper mixing in parts of the SO47,48.

Modelled diatom chl-a was highest in MLDs shallower than 100 m and declined sharply in MLDs exceeding 150 m (Supplementary Fig. 4). In contrast, haptophyte chl-a was higher in MLDs >150 m, while cryptophyte chl-a was largely restricted to MLDs less than 50 m (Supplementary Fig. 4). The reduced light availability in deeper MLDs may have contributed to the observed decline in diatoms on the Antarctic Shelf, whereas haptophytes can tolerate deeper MLDs, where there is lower light availability, as demonstrated in previous studies49,50. Similarly, cryptophytes have a fast photoregulatory response and can adapt efficiently to varying light conditions29, which may explain their prevalence in rapidly changing environments such as West Antarctica19,39,51.

These relationships are reflected in the primarily negative correlation of diatoms with MLD on the shelf versus the positive correlation of haptophytes in regions such as the Ross Sea and Prydz Bay (Fig. 5). Cryptophytes, meanwhile, were generally negatively correlated with MLD across most areas.

West Antarctic waters underwent a pronounced freshening over the study period (Fig. 4) consistent with melting sea ice and glacial input, coincident with reported cryptophyte expansion in this region39,51. Conversely, there was a marginal increase in sea surface salinity (SSS) in the Ross Sea and Prydz Bay, possibly due to deeper mixing with saltier subsurface water and a larger increase in SSS in the East Indian sector of the SO.

Both cryptophytes and diatoms increased in modelled chl-a at lower SSS (Supplementary Fig. 4), matching their negative correlation with SSS (Fig. 5). Cryptophyte chl-a was highest in the SSS range ~32–33 practical salinity units (PSU), whereas diatom chl-a was highest below 32 PSU. In contrast, haptophyte-modelled abundances were greatest in more saline waters and showed positive correlations with SSS (Fig. 5), suggesting that they can tolerate higher salinities such as those found in deeper mixed layers.

Although both ocean and atmospheric warming have been regionally prevalent around Antarctica47,52, this is difficult to discern from satellite data because of the constraints of sea-ice cover, limiting high-latitude sea surface temperature (SST) observations (Fig. 5). However, satellite observations have shown that warming has occurred in the West Antarctic peninsula, an area with rapid cryptophyte proliferation20,39,51. These findings imply that continued warming could shift phytoplankton assemblages towards smaller, flagellate-dominated communities, although other factors (for example, Fe limitation/input, grazing and sea-ice retreat) will undoubtedly modulate these outcomes.

Modelled diatom chl-a was highest at SST below 0 °C, with a secondary peak between ~0 °C and 5 °C (Supplementary Fig. 4). Haptophyte and cryptophyte chl-a increased with SST, although some haptophytes showed elevated chl-a at sub-zero SSTs, despite their maximum model abundance around 7 °C (Supplementary Fig. 4). Cryptophyte abundance was lowest below 0 °C but rapidly increased at SST of 1–2 °C (Supplementary Fig. 4). Correlations further indicated that diatoms were broadly negatively associated with SST, whereas haptophytes and cryptophytes were positively associated (Fig. 5).

Biogeochemical and ecological considerations

The models indicate that changes in environmental conditions are likely to be causing shifts in phytoplankton assemblages that will have broader implications for Antarctic biogeochemistry and ecosystems. In particular, reduced diatom productivity in austral summer has the capacity to alter both trophic dynamics and carbon export. Krill selectively target diatoms and feed less efficiently on small flagellates3,53, whereas salps are efficient, non-selective feeders more suited to many different phytoplankton groups, including haptophytes and cryptophytes54,55. This implies that a reduction in diatoms may favour salps at the expense of krill56, and the resulting decrease in Antarctic diatoms could shift zooplankton populations from a krill- to salp-dominated ecosystem5,53.

While model- or satellite-based products on the circumpolar distribution of Antarctic krill are not available for comparison, in situ observations from more than 11,000 sample stations from 1926 to 2014 indicate a 59% reduction in the biomass density of Antarctic krill since the 1970s5. As krill are a keystone species in the Antarctic marine ecosystem, their decline further threatens the populations of their predators at higher trophic levels57,58.

Diatoms are disproportionately important in the BCP due to their dense silica frustules, which can support rapid sinking rates that facilitate export flux to the deep ocean57,58. From the perspective of carbon cycling, a decline in diatoms would weaken the BCP and potentially lead to a positive feedback on climate change via a decrease in ocean carbon uptake. This feedback may be important given that these high-latitude waters are a more important carbon sink than previously considered59. Additionally, shifts from krill- to salp-dominated grazing—resulting from the decline in diatoms—may further weaken the BCP, as krill have dense faecal pellets that efficiently export carbon to the depths of the ocean60. While salps also produce large faecal pellets61, they are more susceptible to disaggregation, reducing vertical transfer efficiency62.

Conclusions

Our results indicate a net decrease of ~0.32 mg chl-a m−3 (mean of Sen slopes) in diatom chl-a on the Antarctic Shelf over the 1997–2023 period, compared to their climatological mean of 0.97 mg chl-a m−3, although diatom abundance may have recovered somewhat since 2017 coincident with widespread sea-ice loss. During the same period, our models suggest that cryptophytes and haptophytes increased by ~0.23 and ~0.08 mg chl-a m−3, respectively, suggesting a reorganization of summer phytoplankton communities in the Antarctic Shelf. These changes align with major shifts in environmental drivers, including sea ice, reduced iron availability and rising surface temperatures—factors that will continue reshaping Antarctic phytoplankton communities in the coming decade.

The concurrent change in phytoplankton community composition and the regime shift in sea-ice coverage highlights the sensitivity of the Antarctic marine ecosystems to climate change. By integrating environmental data with models trained on multivoyage phytoplankton pigments, this study has demonstrated how satellite observations can identify long-term changes in environmental conditions linked to taxonomic shifts in phytoplankton community composition. Whether the post-2017 diatom recovery will persist remains uncertain. Sustained multiyear observations, especially from missions such as the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) plankton, aerosol, cloud and ocean ecosystem (PACE) satellite, are crucial to determine if these trends represent a stable reversal or a transient response to recent environmental anomalies. Regardless, the long-term decline in Antarctic diatoms and associated significant shifts in phytoplankton community structure highlight the need for ongoing biophysical monitoring and research to better understand climate-related variability across the Antarctic biome.

Methods

Modelling phytoplankton groups

For machine learning training data, we used the dataset of ref. 25, which provides chl-a concentrations of different phytoplankton groups determined using the phytoclass software35. The dataset consists of 14,824 in situ pigment samples, with the majority of data collected during summer months. Frontal regions were identified using the dataset of ref. 66, whereas the Antarctic Shelf break was taken from ref. 63. The data encompass seven phytoplankton groups: diatoms, haptophytes, cryptophytes, green algae, dinoflagellates, pelagophytes and Synechococcus. Of the samples, 44% (n = 6,544) were taken on the Antarctic Shelf and 27% (n = 3,941) were taken in the SSIZ (defined using the American National Snow and Ice Data Centre baseline median value of the maximum winter sea-ice extent between 1991 and 2020). The distribution of sampling in the Antarctic Shelf was circumpolar; however, the Ross Sea and West Antarctic Peninsula had the highest number of samples. Comparatively, the Weddell Sea was largely undersampled, with no samples available in this part of the Antarctic Shelf (Supplementary Fig. 5). The dataset was filtered to exclude any data that were deeper than the MLD. We focused on December–February (peak austral summer) to maximize spatial coverage of satellite ocean-colour data and align with the majority of available in situ pigment samples (Supplementary Fig. 5). We therefore note that any phenological shifts occurring earlier or later in the season could be partly missed in our analysis.

We developed models based on various environmental data to estimate chl-a concentration at the 9-km monthly scale for each phytoplankton group. To enhance the robustness of the analysis, we used a random-forest algorithm67, which is a machine learning approach known for its accuracy and stability in predictions. To assess the performance of each model, the proportion of the variance explained (R2), the mean absolute error (MAE; equation (1)) and root-mean-square error (RMSE; equation (2)) and bias (Bias; equation (3)) were assessed.

where True is the measured value, Est is the estimated value, N is the number of values and i is the sample index.

Results from the random-forest analyses showed strong predictive capabilities for different phytoplankton groups, with high R2 for diatoms, haptophytes and cryptophytes, along with low RMSE, MAE and Bias. The predictability for Synechococcus was lower, with an R2 of 0.57; however, because of their thermal tolerances, they are not present within the study area (mean chl-a concentrations near zero). Similarly, the predictability for dinoflagellates was lower (R2 of 0.55).

To address uncertainty within the models, three techniques were used:

-

(1)

A perturbation study to understand the sensitivity of the model to errors within the training data

-

(2)

Recreation of each individual model using different random seeds, to understand variability in the random nature of the ‘random-forest’ algorithm

-

(3)

Bootstrapping to resample the data with replacement to determine the 2.5th and 97.5th percentiles for confidence intervals on all analysis using the model

For the perturbation study, we first calculated standard deviation for each variable in the training set. Following this, we considered a series of perturbation levels ranging from 0 to 1 (in increments of 0.1). For a given predictor and a specified perturbation level, we generated a new, perturbed version of the dataset by adding an offset equal to the perturbation level multiplied by the standard deviation of the predictor to the original values of that predictor. Using the random-forest model, we then generated predictions based on each perturbed dataset. We evaluate the performance of the model on these perturbed datasets by calculating the R² and comparing the predictions of the model against the observed response values. This approach allowed us to systematically assess the sensitivity of the model to errors in each predictor variable. By observing how the R² varies with incremental perturbations (up to 1 s.d.) for each predictor, we determined which inputs the model is most sensitive to and evaluate its overall robustness.

The results from the perturbation analysis (Supplementary Fig. 6) show that the model is largely insensitive to errors within the training data—the model retains high predictive capabilities, despite errors up to 1 s.d. of the in situ values. Errors in chl-a concentrations had the largest impact on model accuracy; however, even with errors ranging up to 1 mg chl-a m−3, model R2 values were above 0.75.

To quantify variability within the random-forest models for diatoms, haptophytes and cryptophytes, we trained each model ten times (using different random seeds). All subsequent analyses (Sen slopes and significances), were calculated on each of these ten independent models to determine standard deviations in the outputs. For the final correlation estimates with environmental drivers, we used the ensemble mean of the monthly predictions from the ten model runs.

We used a bootstrapping approach to quantify uncertainty in our trend estimates. Specifically, for each trend calculation, we randomly resampled the dataset with replacement 10,000 times. We then recalculated the average Sen slope for each resampled set. The resulting distribution of slopes provided an empirical basis for estimating confidence intervals, with the lower and upper bounds taken from the 2.5th and 97.5th percentiles of the bootstrapped distribution, from which we could determine the 95% confidence intervals.

Model variable selection

Given that environmental conditions play a crucial role in determining the biomass and phenology of phytoplankton types, we incorporated various environmental parameters obtained from satellites and a data-constrained model in our analysis. To construct predictive models that achieve a balance between simplicity and accuracy, a semiparsimonious approach was adopted. This involved a selection of ten variables for each model. The environmental variables selected were:

-

SST (European Space Agency SST Climate Change Initiative, ESA SST CCI)64

-

SSS (estimating the circulation and climate of the ocean (ECCO)-Darwin)26

-

MLD (Suga criteria; ECCO-Darwin)26

-

phosphate (ECCO-Darwin)26

-

nitrate (ECCO-Darwin)26

-

partial pressure of CO2 (ECCO-Darwin)26

-

surface-ocean iron concentration (ECCO-Darwin)26

-

alkalinity (ECCO-Darwin)26

Owing to the highly scattering nature of sea ice and assumption of a dark ocean surface to derive photosynthetically active radiation (PAR), there is large uncertainty in areas of sea-ice cover for remotely sensed PAR. In the level-4 products offered by NASA, masks are applied over areas of historic sea-ice cover68. As many in situ samples used in this study are from the Antarctic coast, PAR products do not cover the coastal sampling locations, which were obtained in areas of historic landfast sea ice. As such, we did not consider PAR in our analysis.

To train the random-forest models, in situ chl-a data were used. However, owing to the limited spatiotemporal coverage of in situ data, we selected the OC-CCI69 product for extrapolation. The merged OC-CCI product was used as it increases spatiotemporal resolution and the number of observations for a given pixel, while minimizing differences between satellites and sensors, making it optimal for long-term trend analysis. This product has been used successfully in other SO studies to understand the interannual dynamics and seasonality of chl-a21. The ESA SST CCI64 was used as it provides robust gap-free measurements of SST while minimizing biases between different satellite radiometers (AVHRR, SLSTS and ATSR), providing a consistent product.

Biogeochemical analysis from ECCO-Darwin description

For variables not observable from space, the ECCO-Darwin model was used. A detailed description of the ECCO-Darwin model is presented in ref. 26. The solution is based on ocean circulation and physical tracers (that is, temperature, salinity and sea ice) from the ECCO LLC270 global-ocean and sea-ice data synthesis. The ECCO-Darwin global-ocean biogeochemistry simulation covered the ocean-colour satellite record and recent work has demonstrated the skill of the model in representing space–time variability in global-ocean carbon cycling70. The ECCO-Darwin model includes the cycling of carbon, nutrients, oxygen and alkalinity. Matter is cycled from inorganic nutrients, through living and dead organic matter and remineralized back to inorganic forms.

Physical observations are assimilated using the adjoint method, which minimizes a weighted least squares sum of model-data misfit (the cost function) to optimize initial conditions, time-varying surface-ocean boundary conditions and time-invariant, three-dimensional mixing coefficients for along-isopycnal, cross-isopycnal and isopycnal thickness diffusivity71,72. The biogeochemical initial conditions and model parameters are optimized using a low-dimensional Green’s functions approach73 after the optimization of the physical model. The mixing coefficients from the adjoint optimization are applied to both the physical and biogeochemical fields. The biogeochemical observations used to evaluate and adjust ECCO-Darwin include monthly-gridded data from surface-ocean CO2 atlas (SOCAT v.5 2023)74, GLODAP ship-based profiles75 and BGC-Argo float profiles76.

Model masking and validation

To ensure consistent spatial resolution, all data were converted to NetCDF format and bilinearly interpolated to a 9-km grid using the terra package in R (ref. 77). To obtain a measurement of each variable at the corresponding space–time location for each pigment sample, the spatial mean of the nearest neighbour to the in situ value was selected and the spatial mean of the eight surrounding pixels.

When making predictions using a model, we were careful to avoid extrapolating beyond the environmental data range covered by the training dataset. We used the ‘minimum–maximum method’78, which masks out predictions in geographic areas where the environmental conditions exceed the range observed in the training dataset. Specifically, variables above the 99th percentile or below the first percentile of the entire range of the exploratory data were masked out to ensure that predictions remained within the bounds of the training dataset. Furthermore, in areas of persistent multiyear ice, a sea-ice mask was used and only samples with at least 5 years of data were considered for trend analysis (Supplementary Fig. 7). We ensured consistency between the number of pixels for each month and the climatological mean for a given month by applying a mask to the climatological mean to account for month-to-month variability in SIC, cloud-cover or other reasons that may cause unavailable satellite detection. This ensured that the number of pixels and spatial extent between the climatology and individual month were the same.

To evaluate the performance of each model and mitigate the risk of overfitting, we conducted K-fold cross-validation using the caret package79 in the R programming language. The training dataset was divided into K equally sized folds, with each fold used as the training data to fit the model, while the remaining folds were held for validation to assess the performance of the model. In our analysis, we set K = 10, which is a commonly used value in cross-validation techniques79. To ensure that training and testing data did not come from the same voyage, the training data were stratified based on voyages. The average performance across all folds was then used to evaluate the final performance of the model (Table 1).

To further scrutinize model performances, relationships between environmental characteristics and each group were assessed. Partial dependence plots were created using the method of ref. 80, which calculates the average prediction made by the random-forest model for the variable across all observations, while averaging out the effects of other variables in the model (Supplementary Fig. 1). The partial dependence plots illustrate the marginal effect of one predictor on the predicted chl-a of a specific group, providing insight into how changes in that particular variable will affect a particular group.

Statistical analysis (trends and correlations)

To examine temporal patterns in phytoplankton, we calculated the monthly chl-a climatologies for each phytoplankton group (as well as their chl-a proportions) across all pixels. To determine the proportional chl-a, the chl-a for a specific group was normalized by the sum of chl-a for all groups. Monthly anomalies (value minus monthly climatological mean) for the proportions (and chl-a concentration) of each group were then derived at monthly time steps.

The analysis focused on austral summer trends during 1997–2023, which comprise the recent period of uninterrupted ocean-colour satellite data. We used a seasonal trend decomposition to decompose each time series using LOESS approach81. This method applies LOESS by fitting localized regression lines between data points, resulting in a smoothed curve that represents the trend of a time series (for example, Fig. 1b,c).

The output of the ten random-forest models for each phytoplankton group were averaged together. These averaged models were used to determine correlations between environmental drivers and different phytoplankton groups, and to calculate climatologies and anomalies. Anomalies for each group were then correlated against the anomalies for each environmental driver, using Spearman’s correlation.

To determine linear trends, we calculated the Sen slope from the monthly anomalies for each model. The Sen slope represents the median slope for all pairs of points in the time series and is insensitive to outliers, providing a robust non-parametric method for estimating linear trends (for example, Fig. 2b)82. The statistical significance of trends was assessed at the 95% confidence level using the Mann–Kendall test with autocorrelation correction using the method of ref. 83 (Supplementary Fig. 8). To account for uncertainty across the ten model outputs, we applied Fisher’s combined probability test by computing the statistic \(x=-2{\sum }_{i=1}^{10}\mathrm{ln}\left({p}_{i}\right)\) at each pixel and comparing it to a chi-square distribution with 20 d.f. (each P value contributes 2 d.f.). This procedure produced a single, aggregated P value that robustly represents the combined evidence from all models. Distributions on the number of trends that show positive and negative slopes were assessed (Supplementary Fig. 9) Standard deviations from the Sen slopes of the ten identical models were assessed to understand variability present within the models (Supplementary Fig. 10).

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

All monthly data generated for the chl-a concentrations for the three phytoplankton groups used in this study (diatoms, haptophytes and cryptophytes) at 9-km resolution are available via Zenodo at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15593919 (ref. 84). Data for the SST CCI product can be found at https://climate.esa.int/en/projects/sea-surface-temperature/ (refs. 64,65). Data for the OC-CCI can be found at https://climate.esa.int/en/projects/ocean-colour/ (ref. 69). ECCO-Darwin model output is available at the ECCO data portal https://data.nas.nasa.gov/ecco/data.php?dir=/eccodata/llc_270/ecco_darwin_v5/ (ref. 70). Model code and platform-independent instructions for running ECCO-Darwin simulations are available via Github at https://github.com/MITgcm-contrib/ecco_darwin (ref. 70). SO fronts were acquired from the Australian Antarctic Data Centre which are available at https://data.aad.gov.au/metadata/records/antarctic_circumpolar_current_fronts/citation (ref. 66).

Code availability

The code used to generate phytoplankton models and associated analysis are available via Github at https://github.com/alexanderhayward1995/NClim_code.git (ref. 85).

References

Basu, S. & Mackey, K. Phytoplankton as key mediators of the biological carbon pump: their responses to a changing climate. Sustainability 10, 869 (2018).

Smith, W. O., Ainley, D. G., Arrigo, K. R. & Dinniman, M. S. The oceanography and ecology of the Ross Sea. Annu. Rev. Mar. Sci. 6, 469–487 (2014).

Haberman, K. L., Ross, R. M. & Quetin, L. B. Diet of the Antarctic krill (Euphausia superba Dana): II. Selective grazing in mixed phytoplankton assemblages. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 283, 97–113 (2003).

Atkinson, A. et al. Krill (Euphausia superba) distribution contracts southward during rapid regional warming. Nat. Clim. Change 9, 142–147 (2019).

Atkinson, A., Siegel, V., Pakhomov, E. & Rothery, P. Long-term decline in krill stock and increase in salps within the Southern Ocean. Nature 432, 100–103 (2004).

Tréguer, P. et al. Influence of diatom diversity on the ocean biological carbon pump. Nat. Geosci. 11, 27–37 (2018).

Raphael, M. N. & Handcock, M. S. A new record minimum for Antarctic sea ice. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 3, 215–216 (2022).

Purich, A. & Doddridge, E. W. Record low Antarctic sea ice coverage indicates a new sea ice state. Commun. Earth Environ. 4, 314 (2023).

Hobbs, W. et al. Observational evidence for a regime shift in summer Antarctic sea ice. J. Clim. 37, 2263–2275 (2024).

Nakayama, Y., Menemenlis, D., Zhang, H., Schodlok, M. & Rignot, E. Origin of circumpolar deep water intruding onto the Amundsen and Bellingshausen Sea continental shelves. Nat. Commun. 9, 3403 (2018).

Flexas, M. M., Thompson, A. F., Schodlok, M. P., Zhang, H. & Speer, K. Antarctic Peninsula warming triggers enhanced basal melt rates throughout West Antarctica. Sci. Adv. 8, eabj9134 (2022).

Deppeler, S. L. & Davidson, A. T. Southern Ocean phytoplankton in a changing climate. Front. Mar. Sci. 4, 40 (2017).

Constable, A. J. et al. Climate change and Southern Ocean ecosystems I: how changes in physical habitats directly affect marine biota. Glob. Change Biol. 20, 3004–3025 (2014).

Henley, S. F. et al. Changing biogeochemistry of the Southern Ocean and its ecosystem implications. Front. Mar. Sci. 7, 581 (2020).

Sallée, J.-B. et al. Summertime increases in upper-ocean stratification and mixed-layer depth. Nature 591, 592–598 (2021).

Boyd, P. W., Strzepek, R., Fu, F. & Hutchins, D. A. Environmental control of open‐ocean phytoplankton groups: now and in the future. Limnol. Oceanogr. 55, 1353–1376 (2010).

Tagliabue, A. ‘Oceans are hugely complex’: modelling marine microbes is key to climate forecasts. Nature 623, 250–252 (2023).

Ducklow, H. W. et al. Marine pelagic ecosystems: the West Antarctic Peninsula. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B 362, 67–94 (2007).

Moline, M. A., Claustre, H., Frazer, T. K., Schofield, O. & Vernet, M. Alteration of the food web along the Antarctic Peninsula in response to a regional warming trend. Glob. Change Biol. 10, 1973–1980 (2004).

Schofield, O. et al. Changes in the upper ocean mixed layer and phytoplankton productivity along the West Antarctic Peninsula. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 376, 20170173 (2018).

Thomalla, S. J., Nicholson, S.-A., Ryan-Keogh, T. J. & Smith, M. E. Widespread changes in Southern Ocean phytoplankton blooms linked to climate drivers. Nat. Clim. Change 13, 975–984 (2023).

Del Castillo, C. E., Signorini, S. R., Karaköylü, E. M. & Rivero‐Calle, S. Is the Southern Ocean getting greener? Geophys. Res. Lett. 46, 6034–6040 (2019).

Pinkerton, M. H. et al. Evidence for the impact of climate change on primary producers in the Southern Ocean. Front. Ecol. Evol. 9, 592027 (2021).

Cael, B. B., Bisson, K., Boss, E., Dutkiewicz, S. & Henson, S. Global climate-change trends detected in indicators of ocean ecology. Nature 619, 551–554 (2023).

Hayward, A., Pinkerton, M. H., Wright, S. W., Gutiérrez-Rodriguez, A. & Law, C. S. Twenty-six years of phytoplankton pigments reveal a circumpolar class divide around the Southern Ocean. Commun. Earth Environ. 5, 92 (2024).

Carroll, D. et al. The ECCO‐Darwin data‐assimilative global ocean biogeochemistry model: estimates of seasonal to multidecadal surface ocean pCO2 and air–sea CO2 flux. J. Adv. Model. Earth Syst. 12, e2019MS001888 (2020).

Wright, S. W. et al. Phytoplankton community structure and stocks in the Southern Ocean (30–80° E) determined by CHEMTAX analysis of HPLC pigment signatures. Deep Sea Res. II 57, 758–778 (2010).

Laws, E. A. & Bannister, T. T. Nutrient‐ and light‐limited growth of Thalassiosira fluviatilis in continuous culture, with implications for phytoplankton growth in the ocean. Limnol. Oceanogr. 25, 457–473 (1980).

Geider, R. J., Maclntyre, H. L. & Kana, T. M. A dynamic regulatory model of phytoplanktonic acclimation to light, nutrients, and temperature. Limnol. Oceanogr. 43, 679–694 (1998).

Sosik, H. M. & Olson, R. J. Phytoplankton and iron limitation of photosynthetic efficiency in the Southern Ocean during late summer. Deep Sea Res. I 49, 1195–1216 (2002).

Strzepek, R. F., Maldonado, M. T., Hunter, K. A., Frew, R. D. & Boyd, P. W. Adaptive strategies by Southern Ocean phytoplankton to lessen iron limitation: uptake of organically complexed iron and reduced cellular iron requirements. Limnol. Oceanogr. 56, 1983–2002 (2011).

Sunda, W. G. & Huntsman, S. A. Iron uptake and growth limitation in oceanic and coastal phytoplankton. Mar. Chem. 50, 189–206 (1995).

Sathyendranath, S. et al. Carbon-to-chlorophyll ratio and growth rate of phytoplankton in the sea. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 383, 73–84 (2009).

Kropuenske, L. R. et al. Photophysiology in two major Southern Ocean phytoplankton taxa: photoprotection in Phaeocystis antarctica and Fragilariopsis cylindrus. Limnol. Oceanogr. 54, 1176–1196 (2009).

Hayward, A., Pinkerton, M. H. & Gutierrez‐Rodriguez, A. phytoclass: a pigment‐based chemotaxonomic method to determine the biomass of phytoplankton classes. Limnol. Oceanogr. Methods 21, 220–241 (2023).

Mangoni, O. et al. Phaeocystis antarctica unusual summer bloom in stratified Antarctic coastal waters (Terra Nova Bay, Ross Sea). Mar. Environ. Res. 151, 104733 (2019).

Arrigo, K. R., Weiss, A. M. & Smith, W. O. Physical forcing of phytoplankton dynamics in the southwestern Ross Sea. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 103, 1007–1021 (1998).

Fisher, B. J. et al. Climate-driven shifts in Southern Ocean primary producers and biogeochemistry in CMIP6 models. Biogeosciences 22, 975–994 (2025).

Mendes, C. R. B. et al. Cryptophytes: an emerging algal group in the rapidly changing Antarctic Peninsula marine environments. Glob. Change Biol. 29, 1791–1808 (2023).

Ryan-Keogh, T. J., Thomalla, S. J., Monteiro, P. M. S. & Tagliabue, A. Multidecadal trend of increasing iron stress in Southern Ocean phytoplankton. Science 379, 834–840 (2023).

Boyd, P. W. Physiology and iron modulate diverse responses of diatoms to a warming Southern Ocean. Nat. Clim. Change 9, 148–152 (2019).

Lizotte, M. P. The contributions of sea ice algae to Antarctic marine primary production. Am. Zool. 41, 57–73 (2001).

Yan, D. et al. Response to sea ice melt indicates high seeding potential of the ice diatom Thalassiosira to spring phytoplankton blooms: a laboratory study on an ice algal community from the Sea of Okhotsk. Front. Mar. Sci. 7, 613 (2020).

Höfer, J. et al. The role of water column stability and wind mixing in the production/export dynamics of two bays in the Western Antarctic Peninsula. Prog. Oceanogr. 174, 105–116 (2019).

Pinkerton, M. H. & Hayward, A. Estimating variability and long-term change in sea ice primary productivity using a satellite-based light penetration index. J. Mar. Syst. 221, 103576 (2021).

Bennetts, L. G. et al. Closing the loops on Southern Ocean dynamics: from the circumpolar current to ice shelves and from bottom mixing to surface waves. Rev. Geophys. 62, e2022RG000781 (2024).

Fogt, R. L. & Marshall, G. J. The Southern Annular Mode: variability, trends, and climate impacts across the Southern Hemisphere. WIREs Clim. Change 11, e652 (2020).

Martínez-Moreno, J. et al. Global changes in oceanic mesoscale currents over the satellite altimetry record. Nat. Clim. Change 11, 397–403 (2021).

Moisan, T. A. & Mitchell, B. G. Photophysiological acclimation of Phaeocystis antarctica Karsten under light limitation. Limnol. Oceanogr. 44, 247–258 (1999).

Arrigo, K. R. et al. Photophysiology in two major Southern Ocean phytoplankton taxa: photosynthesis and growth of Phaeocystis antarctica and Fragilariopsis cylindrus under different irradiance levels. Integr. Comp. Biol. 50, 950–966 (2010).

Mendes, C. R. B. et al. New insights on the dominance of cryptophytes in Antarctic coastal waters: a case study in Gerlache Strait. Deep Sea Res. II 149, 161–170 (2018).

Schmidtko, S., Heywood, K. J., Thompson, A. F. & Aoki, S. Multidecadal warming of Antarctic waters. Science 346, 1227–1231 (2014).

Johnston, N. M. et al. Status, change, and futures of zooplankton in the Southern Ocean. Front. Ecol. Evol. 9, 624692 (2022).

Von Harbou, L. et al. Salps in the Lazarev Sea, Southern Ocean: I. Feeding dynamics. Mar. Biol. 158, 2009–2026 (2011).

Alcaraz, M. et al. Changes in the C, N, and P cycles by the predicted salps–krill shift in the southern ocean. Front. Mar. Sci. 1, 45 (2014).

Pakhomov, E. A., Froneman, P. W. & Perissinotto, R. Salp/krill interactions in the Southern Ocean: spatial segregation and implications for the carbon flux. Deep Sea Res. II 49, 1881–1907 (2002).

Hill, S. L., Phillips, T. & Atkinson, A. Potential climate change effects on the habitat of Antarctic krill in the Weddell quadrant of the Southern Ocean. PLoS ONE 8, e72246 (2013).

Klein, E. S., Hill, S. L., Hinke, J. T., Phillips, T. & Watters, G. M. Impacts of rising sea temperature on krill increase risks for predators in the Scotia Sea. PLoS ONE 13, e0191011 (2018).

Dong, Y. et al. Direct observational evidence of strong CO2 uptake in the Southern Ocean. Sci. Adv. 10, eadn5781 (2024).

Trinh, R., Ducklow, H. W., Steinberg, D. K. & Fraser, W. R. Krill body size drives particulate organic carbon export in West Antarctica. Nature 618, 526–530 (2023).

Décima, M. et al. Salp blooms drive strong increases in passive carbon export in the Southern Ocean. Nat. Commun. 14, 425 (2023).

Iversen, M. H. et al. Sinkers or floaters? Contribution from salp pellets to the export flux during a large bloom event in the Southern Ocean. Deep Sea Res. II 138, 116–125 (2017).

Amblas, D. Antarctic continental shelf break (shapefile) [dataset]. PANGAEA https://doi.org/10.1594/PANGAEA.890863 (2018).

Merchant, C. J. et al. Sea surface temperature datasets for climate applications from phase 1 of the European Space Agency Climate Change Initiative (SST CCI). Geosci. Data J. 1, 179–191 (2014).

Lavergne, T. et al. Version 2 of the EUMETSAT OSI SAF and ESA CCI sea-ice concentration climate data records. Cryosphere 13, 49–78 (2019).

Orsi, A. H. & Harris, U. Fronts of the Antarctic Circumpolar Current—GIS data, version 1. Australian Antarctic Data Centre https://data.aad.gov.au/metadata/antarctic_circumpolar_current_fronts (2019).

Belgiu, M. & Drăguţ, L. Random forest in remote sensing: a review of applications and future directions. ISPRS J. Photogram. Remote Sens. 114, 24–31 (2016).

Frouin, R., McPherson, J., Ueyoshi, K. & Franz, B. A. A time series of photosynthetically available radiation at the ocean surface from SeaWiFS and MODIS data. In Proc. Volume 8525, Remote Sensing of the Marine Environment II (eds Frouin, R. J. et al.) 852519 (SPIE, 2012); https://doi.org/10.1117/12.981264

Sathyendranath, S. et al. An ocean-colour time series for use in climate studies: the experience of the ocean-colour climate change initiative (OC-CCI). Sensors 19, 4285 (2019).

Carroll, D. et al. Attribution of space–time variability in global‐ocean dissolved inorganic carbon. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 36, e2021GB007162 (2022).

Wunsch, C. & Heimbach, P. Dynamically and kinematically consistent global ocean circulation and ice state estimates. Int. Geophys. 103, 553–579 (2013).

Wunsch, C., Heimbach, P., Ponte, R. & Fukumori, I. The global general circulation of the ocean estimated by the ECCO-Consortium. Oceanography 22, 88–103 (2009).

Menemenlis, D., Fukumori, I. & Lee, T. Using Green’s functions to calibrate an ocean general circulation model. Mon. Weather Rev. 133, 1224–1240 (2005).

Bakker, D. C. E. et al. An update to the Surface Ocean CO2 Atlas (SOCAT version 2). Earth Syst. Sci. Data 6, 69–90 (2014).

Lauvset, S. K. et al. The annual update GLODAPv2.2023: the global interior ocean biogeochemical data product. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 16, 2047–2072 (2024).

Riser, S. C. et al. Fifteen years of ocean observations with the global Argo array. Nat. Clim. Change 6, 145–153 (2016).

Hijmans, R. J. et al. terra. R package version 1.6-22 https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/terra/index.html (2022).

Pinkerton, M. H. et al. Zooplankton in the Southern Ocean from the continuous plankton recorder: distributions and long-term change. Deep Sea Res. I 162, 103303 (2020).

Kuhn, M. Building predictive models in R using the caret package. J. Stat. Softw. 28, 1–26 (2008).

Friedman, J. H. Greedy function approximation: a gradient boosting machine. Ann. Stat. 29, 1189–1232 (2001).

Cleveland, R. B., Cleveland, W. S., McRae, J. E. & Terpenning, I. STL: a seasonal-trend decomposition. J. Stat. 6, 3–73 (1990).

Sen, P. K. Estimates of the regression coefficient based on Kendall’s Tau. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 63, 1379–1389 (1968).

Yue, S. & Wang, C. The Mann–Kendall test modified by effective sample size to detect trend in serially correlated hydrological series. Water Resour. Manag. 18, 201–218 (2004).

Hayward, A. & Pinkerton, M. Monthly ensemble mean chlorophyll-a concentration for Antarctic phytoplankton groups (1997–2023) [Data set]. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15593919 (2025).

Hayward, A. NClim_code. GitHub https://github.com/alexanderhayward1995/NClim_code (2025).

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge NIWA for providing funding through the PhD scholarship (CDPS2001) and the University of Otago (Department of Marine Science) for their support throughout the PhD programme. We are also grateful to the New Zealand MBIE Endeavour Programme C01X1710 (Ross-RAMP), Antarctic Science Platform, Project 3 (MBIE contract no. ANTA1801), MBIE NIWA SSIF (‘Structure and function of marine ecosystems’) for financial support. Furthermore, we are grateful to the NCKF for financial support and New Zealand’s eScience infrastructure for use of their high-performance computer. We thank the PHYTO-CCI programme for support. We acknowledge the contribution to this work by the R open-source collective and R Studio. A.H. thanks Hank Green for creating accessible educational resources, which provided valuable inspiration during early scientific training. P.W. is supported through the Australian Government as part of the Antarctic Science Collaboration Initiative programme and contributes to Project 6 (sea ice) of the Australian Antarctic Program Partnership (project ID ASCI000002). P.W. also acknowledges the support through the Biogeochemical Exchanges Processes at Sea Ice Interfaces (BEPSII) Early Career Researcher exchange program with funds from the Surface Ocean-Lower Atmosphere Study (SOLAS), which is partially supported by the US National Science Foundation (Grants OCE-2140395 and 2513154) via the Scientific Committee on Oceanic Research (SCOR). D.C. acknowledges support from the NASA ocean biology and biogeochemistry, carbon cycle science and carbon monitoring systems programmes.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.H., S.W.W., D.C., P.W. and M.H.P. conducted the analysis. The paper was written and edited by A.H., S.W.W., D.C., P.W., C.S.L., A.G.-R. and M.H.P. The conceptual framework was developed by A.H., S.W.W., C.S.L., A.G.-R. and M.H.P.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Climate Change thanks Katherina Petrou and Oscar Schofield for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figs. 1–10, discussion and references.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hayward, A., Wright, S.W., Carroll, D. et al. Antarctic phytoplankton communities restructure under shifting sea-ice regimes. Nat. Clim. Chang. 15, 889–896 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-025-02379-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-025-02379-x

This article is cited by

-

Extreme temperature events reshuffle the ecological landscape of the Southern Ocean

Nature Communications (2025)

-

Emerging evidence of abrupt changes in the Antarctic environment

Nature (2025)