Abstract

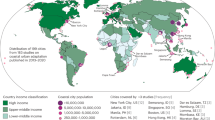

Retreating from coastlines is one potential human response to the increasing threats posed by coastal climate hazards. However, the global extent of coastal settlement retreat, its correlation with local vulnerabilities, and the adaptation gaps remain less understood. Here we analyse night-time light changes for 1992 to 2019 and show that settlements retreated from coastlines in 56% of coastal subnational regions, remained stable in 28%, and moved closer to coastlines in 16% of these regions. Retreat was weakly associated with historical experiences of coastal climate hazards but accelerated in regions with greater vulnerability to coastal climate hazards—indicated by lower infrastructure protection and less adaptive capacity. In 46% of low-income regions, particularly in Africa and Asia, settlements were forced to either maintain their current status quo or move closer to coastlines, revealing the large adaptation gap in addressing future climate change risks.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$32.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $21.58 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

The source data supporting the findings of this study are available via Harvard Dataverse at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/OWYNB0 (ref. 120). Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

The code supporting the findings of this study is available via Zenodo at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.16757827 (ref. 121).

References

Gillis, J. R. The Human Shore: Seacoasts in History (Univ. Chicago Press, 2012).

Bai, X. et al. Six research priorities for cities and climate change. Nature 555, 23–25 (2018).

Honsel, L. E., Reimann, L. & Vafeidis, A. T. Population Development as a Driver of Coastal Risk: Current Trends and Future Pathways (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2023).

Pal, I., Kumar, A. & Mukhopadhyay, A. Risks to coastal critical infrastructure from climate change. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 48, 681–712 (2023).

Nielsen, D. M. et al. Increase in Arctic coastal erosion and its sensitivity to warming in the twenty-first century. Nat. Clim. Change 12, 263–270 (2022).

Bloemendaal, N. et al. A globally consistent local-scale assessment of future tropical cyclone risk. Sci. Adv. 8, eabm8438 (2022).

Dullaart, J. C. M. et al. Accounting for tropical cyclones more than doubles the global population exposed to low-probability coastal flooding. Commun. Earth Environ. 2, 135 (2021).

Tebaldi, C. et al. Extreme sea levels at different global warming levels. Nat. Clim. Change 11, 746–751 (2021).

Mora, C. et al. Broad threat to humanity from cumulative climate hazards intensified by greenhouse gas emissions. Nat. Clim. Change 8, 1062–1071 (2018).

Fuldauer, L. I. et al. Targeting climate adaptation to safeguard and advance the Sustainable Development Goals. Nat. Commun. 13, 3579 (2022).

Fuso Nerini, F. et al. Connecting climate action with other Sustainable Development Goals. Nat. Sustain. 2, 674–680 (2019).

McLeman, R. & Smit, B. Migration as an adaptation to climate change. Climatic Change 76, 31–53 (2006).

Costas, S., Ferreira, O. & Martinez, G. Why do we decide to live with risk at the coast? Ocean Coast. Manage. 118, 1–11 (2015).

Hino, M., Field, C. B. & Mach, K. J. Managed retreat as a response to natural hazard risk. Nat. Clim. Change 7, 364–370 (2017).

Carey, J. Managed retreat increasingly seen as necessary in response to climate change’s fury. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 117, 13182–13185 (2020).

Mård, J., Di Baldassarre, G. & Mazzoleni, M. Nighttime light data reveal how flood protection shapes human proximity to rivers. Sci. Adv. 4, eaar5779 (2018).

Khan, M. R., Huq, S., Risha, A. N. & Alam, S. S. High-density population and displacement in Bangladesh. Science 372, 1290–1293 (2021).

Ekoh, S. S., Teron, L. & Ajibade, I. Climate change and coastal megacities: adapting through mobility. Glob. Environ. Change 80, 102666 (2023).

Ceola, S., Mård, J. & Di Baldassarre, G. Drought and human mobility in Africa. Earths Future 11, e2023EF003510 (2023).

Mach, K. J. & Siders, A. Reframing strategic, managed retreat for transformative climate adaptation. Science 372, 1294–1299 (2021).

Morris, R. L., Boxshall, A. & Swearer, S. E. Climate-resilient coasts require diverse defence solutions. Nat. Clim. Change 10, 485–487 (2020).

Marois, D. E. & Mitsch, W. J. Coastal protection from tsunamis and cyclones provided by mangrove wetlands–a review. Int. J. Biodivers. Sci. Ecosyst. Serv. Manage. 11, 71–83 (2015).

Wang, C.-H., Khoo, Y. B. & Wang, X. Adaptation benefits and costs of raising coastal buildings under storm-tide inundation in South East Queensland, Australia. Climatic Change 132, 545–558 (2015).

Xu, L. et al. Dynamic risk of coastal flood and driving factors: integrating local sea level rise and spatially explicit urban growth. J. Clean. Prod. 321, 129039 (2021).

Haasnoot, M., Lawrence, J. & Magnan, A. K. Pathways to coastal retreat. Science 372, 1287–1290 (2021).

De Sherbinin, A. et al. Preparing for resettlement associated with climate change. Science 334, 456–457 (2011).

Kousky, C. Managing shoreline retreat: a US perspective. Climatic Change 124, 9–20 (2014).

Siders, A., Hino, M. & Mach, K. J. The case for strategic and managed climate retreat. Science 365, 761–763 (2019).

Greiving, S., Du, J. & Puntub, W. Managed retreat—a strategy for the mitigation of disaster risks with international and comparative perspectives. J. Extreme Events 5, 1850011 (2018).

Ajibade, I., Sullivan, M., Lower, C., Yarina, L. & Reilly, A. Are managed retreat programs successful and just? A global mapping of success typologies, justice dimensions, and trade-offs. Glob. Environ. Change 76, 102576 (2022).

Anderson, R. B. The taboo of retreat: the politics of sea level rise, managed retreat, and coastal property values in California. Econ. Anthropol. 9, 284–296 (2022).

Bower, E. R., Badamikar, A., Wong-Parodi, G. & Field, C. B. Enabling pathways for sustainable livelihoods in planned relocation. Nat. Clim. Change 13, 919–926 (2023).

López-Carr, D. & Marter-Kenyon, J. Human adaptation: manage climate-induced resettlement. Nature 517, 265–267 (2015).

Vestby, J., Schutte, S., Tollefsen, A. F. & Buhaug, H. Societal determinants of flood-induced displacement. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 121, e2206188120 (2024).

Hauer, M. E. et al. Sea-level rise and human migration. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 1, 28–39 (2020).

Ronco, M. et al. Exploring interactions between socioeconomic context and natural hazards on human population displacement. Nat. Commun. 14, 8004 (2023).

Mach, K. J. et al. Managed retreat through voluntary buyouts of flood-prone properties. Sci. Adv. 5, eaax8995 (2019).

Pinter, N. & Rees, J. C. Assessing managed flood retreat and community relocation in the Midwest USA. Nat. Hazards 107, 497–518 (2021).

Hoang, T. & Noy, I. The income consequences of a managed retreat. Reg. Sci. Urban Econ. 100, 103896 (2023).

Dannenberg, A. L., Frumkin, H., Hess, J. J. & Ebi, K. L. Managed retreat as a strategy for climate change adaptation in small communities: public health implications. Climatic Change 153, 1–14 (2019).

McCaughey, J. W., Daly, P., Mundir, I., Mahdi, S. & Patt, A. Socio-economic consequences of post-disaster reconstruction in hazard-exposed areas. Nat. Sustain. 1, 38–43 (2018).

Laurice Jamero, M. et al. Small-island communities in the Philippines prefer local measures to relocation in response to sea-level rise. Nat. Clim. Change 7, 581–586 (2017).

Levin, N. et al. Remote sensing of night lights: a review and an outlook for the future. Remote Sens. Environ. 237, 111443 (2020).

Seidel, H. & Lal, P. N. Economic Value of the Pacific Ocean to the Pacific Island Countries and Territories (IUCN, 2010).

Lees, A. & Lees, L. H. Cities and the Making of Modern Europe, 1750–1914 (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2007).

Boustan, L. P., Kahn, M. E., Rhode, P. W. & Yanguas, M. L. The effect of natural disasters on economic activity in US counties: a century of data. J. Urban Econ. 118, 103257 (2020).

Angelucci, M. Migration and financial constraints: evidence from Mexico. Rev. Econ. Stat. 97, 224–228 (2015).

Khatun, F. et al. Environmental non-migration as adaptation in hazard-prone areas: evidence from coastal Bangladesh. Glob. Environ. Change 77, 102610 (2022).

Mallick, B. & Vogt, J. Cyclone, coastal society and migration: empirical evidence from Bangladesh. Int. Dev. Plan. Rev. 34, 217–240 (2012).

Molloy, R., Smith, C. L. & Wozniak, A. Internal migration in the United States. J. Econ. Perspect. 25, 173–196 (2011).

Chen, T. H. Y. & Lee, B. Income-based inequality in post-disaster migration is lower in high resilience areas: evidence from US internal migration. Environ. Res. Lett. 17, 034043 (2022).

Broyles, L. Extreme weather threatens informal settlements. Nat. Clim. Change 14, 428–429 (2024).

Chen, J. & Mueller, V. Coastal climate change, soil salinity and human migration in Bangladesh. Nat. Clim. Change 8, 981–985 (2018).

Arkema, K. K. et al. Coastal habitats shield people and property from sea-level rise and storms. Nat. Clim. Change 3, 913–918 (2013).

Hochard, J. P., Hamilton, S. & Barbier, E. B. Mangroves shelter coastal economic activity from cyclones. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 116, 12232–12237 (2019).

Jackson, L. Frequency and magnitude of events. In Encyclopedia of Natural Hazards Encyclopedia of Earth Sciences Series (ed Bobrowsky, P. T.) 359–363 (Springer, 2013).

Riris, P. et al. Frequent disturbances enhanced the resilience of past human populations. Nature 629, 837–842 (2024).

Lechowska, E. What determines flood risk perception? A review of factors of flood risk perception and relations between its basic elements. Nat. Hazards 94, 1341–1366 (2018).

Demski, C., Capstick, S., Pidgeon, N., Sposato, R. G. & Spence, A. Experience of extreme weather affects climate change mitigation and adaptation responses. Clim. Change 140, 149–164 (2017).

Rentschler, J. et al. Global evidence of rapid urban growth in flood zones since 1985. Nature 622, 87–92 (2023).

You, X. Flood-prone areas are hotspots for urban development. Nature https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-023-03128-w (2023).

Monirul Qader Mirza, M., Minnatullah, K. & Noorisameleh, Z. Climate change and coastal agriculture: can developing countries adapt? Transforming coastal zone for sustainable food and income security. In Proc. International Symposium of ISCAR on Coastal Agriculture (eds Lama, T. D. et al.) 839–846 (Springer, 2022).

Szaboova, L. et al. Evaluating migration as successful adaptation to climate change: trade-offs in well-being, equity, and sustainability. One Earth 6, 620–631 (2023).

Wu, Y. et al. Does flood protection affect urban expansion in the coastal flood-prone area of China? Front. Earth Sci. 10, 951828 (2022).

Andreadis, K. M. et al. Urbanizing the floodplain: global changes of imperviousness in flood-prone areas. Environ. Res. Lett. 17, 104024 (2022).

Lincke, D., Hinkel, J., Mengel, M. & Nicholls, R. J. Understanding the drivers of coastal flood exposure and risk from 1860 to 2100. Earths Future 10, e2021EF002584 (2022).

Druckenmiller, H., Liao, Y., Pesek, S., Walls, M. & Zhang, S. Removing development incentives in risky areas promotes climate adaptation. Nat. Clim. Change 14, 936–942 (2024).

Gao, J. & Bukovsky, M. S. Urban land patterns can moderate population exposures to climate extremes over the 21st century. Nat. Commun. 14, 6536 (2023).

Wang, N. et al. How can changes in the human–flood distance mitigate flood fatalities and displacements? Geophys. Res. Lett. 50, e2023GL105064 (2023).

Ferdous, M. R., Wesselink, A., Brandimarte, L., Di Baldassarre, G. & Rahman, M. M. The levee effect along the Jamuna River in Bangladesh. Water Int. 44, 496–519 (2019).

Tesselaar, M., Botzen, W. W., Tiggeloven, T. & Aerts, J. C. Flood insurance is a driver of population growth in European floodplains. Nat. Commun. 14, 7483 (2023).

Yang, X., Xu, L., Zhang, X. & Ding, S. Spatiotemporal evolutionary patterns and driving factors of vulnerability to natural disasters in China from 2000 to 2020. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 95, 103890 (2023).

Nohrstedt, D., Hileman, J., Mazzoleni, M., Di Baldassarre, G. & Parker, C. F. Exploring disaster impacts on adaptation actions in 549 cities worldwide. Nat. Commun. 13, 3360 (2022).

Nohrstedt, D., Mazzoleni, M., Parker, C. F. & Di Baldassarre, G. Exposure to natural hazard events unassociated with policy change for improved disaster risk reduction. Nat. Commun. 12, 193 (2021).

Babapoorkamani, A. & Ricci, L. Decision-making strategies for climate change adaptation in coastal regions of Africa. Environ. Dev. 55, 101196 (2025).

Schmidt-Thomé, P. et al. Climate Change in Vietnam (Springer, 2015).

Le, T. D. N. Climate change adaptation in coastal cities of developing countries: characterizing types of vulnerability and adaptation options. Mitig. Adapt. Strateg. Glob. Change 25, 739–761 (2020).

Jha, A. et al. Five Feet High and Rising: Cities and Flooding in the 21st Century (World Bank, 2011).

Neal, W. J., Pilkey, O. H., Cooper, J. A. G. & Longo, N. J. Why coastal regulations fail. Ocean Coast. Manage. 156, 21–34 (2018).

Ding, M. et al. Reversal of the levee effect towards sustainable floodplain management. Nat. Sustain. 6, 1578–1586 (2023).

O’Donnell, T. Managed retreat and planned retreat: a systematic literature review. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 377, 20210129 (2022).

Scott, M. et al. Climate disruption and planning: resistance or retreat? Plan. Theory Pract. 21, 125–154 (2020).

Kreibich, H. et al. The challenge of unprecedented floods and droughts in risk management. Nature 608, 80–86 (2022).

Siders, A., Ajibade, I. & Casagrande, D. Transformative potential of managed retreat as climate adaptation. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 50, 272–280 (2021).

Small, C., Pozzi, F. & Elvidge, C. D. Spatial analysis of global urban extent from DMSP-OLS night lights. Remote Sens. Environ. 96, 277–291 (2005).

Gibson, J., Olivia, S., Boe-Gibson, G. & Li, C. Which night lights data should we use in economics, and where? J. Dev. Econ. 149, 102602 (2021).

McCallum, I. et al. Estimating global economic well-being with unlit settlements. Nat. Commun. 13, 2459 (2022).

Huang, X. et al. Toward accurate mapping of 30-m time-series global impervious surface area (GISA). Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 109, 102787 (2022).

Ceola, S., Laio, F. & Montanari, A. Human‐impacted waters: new perspectives from global high‐resolution monitoring. Water Resour. Res. 51, 7064–7079 (2015).

Mellander, C., Lobo, J., Stolarick, K. & Matheson, Z. Night-time light data: a good proxy measure for economic activity? PLoS ONE 10, e0139779 (2015).

Li, X., Zhou, Y., Zhao, M. & Zhao, X. A harmonized global nighttime light dataset 1992–2018. Sci. Data 7, 168 (2020).

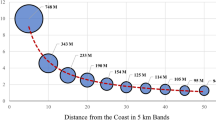

Mokhtari, Z. et al. Nighttime light extent and intensity explain the dynamics of human activity in coastal zones. Sci. Rep. 15, 1663 (2025).

Andrew, N. L., Bright, P., de la Rua, L., Teoh, S. J. & Vickers, M. Coastal proximity of populations in 22 Pacific Island Countries and Territories. PLoS ONE 14, e0223249 (2019).

Das, S. & Vincent, J. R. Mangroves protected villages and reduced death toll during Indian super cyclone. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 106, 7357–7360 (2009).

Deb, M. & Ferreira, C. M. Potential impacts of the Sunderban mangrove degradation on future coastal flooding in Bangladesh. J. Hydroenviron. Res. 17, 30–46 (2017).

Kim, J. S. & Kim, S. K. Ageing population and green space dynamics for climate change adaptation in Southeast Asia. Nat. Clim. Change 14, 490–495 (2024).

Rosvold, E. L. & Buhaug, H. G. D. I. S. A global dataset of geocoded disaster locations. Sci. Data 8, 61 (2021).

Nicholls, R. J., Hinkel, J., Lincke, D. & van der Pol, T. Global Investment Costs for Coastal Defense Through the 21st Century (World Bank, 2019).

Beck, M. W. et al. The global flood protection savings provided by coral reefs. Nat. Commun. 9, 2186 (2018).

Sun, F. & Carson, R. T. Coastal wetlands reduce property damage during tropical cyclones. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 117, 5719–5725 (2020).

van Zelst, V. T. et al. Cutting the costs of coastal protection by integrating vegetation in flood defences. Nat. Commun. 12, 6533 (2021).

Mazor, T. et al. Large conservation opportunities exist in >90% of tropic–subtropic coastal habitats adjacent to cities. One Earth 4, 1004–1015 (2021).

Bunting, P. et al. Global mangrove extent change 1996–2020: global mangrove watch version 3.0. Remote Sens. 14, 3657 (2022).

UNEP-WCMC Ocean+ Habitats v.4.1 (UN Environment World Conservation Monitoring Centre, 2021); https://doi.org/10.34892/t2wk-5t34

Mcowen, C. W. L. et al. A global map of saltmarshes (ver 6.0) Biodivers. Data J. 5, e11764 (2017).

UNEP-WCMC Global Distribution of Seagrasses v.7 (UN Environment World Conservation Monitoring Centre, 2020); http://data.unep-wcmc.org/datasets/7

Engle, N. L. Adaptive capacity and its assessment. Glob. Environ. Change 21, 647–656 (2011).

Jaiswal, K. & Wald, D. An empirical model for global earthquake fatality estimation. Earthq. Spectra 26, 1017–1037 (2010).

He, C. et al. A global analysis of the relationship between urbanization and fatalities in earthquake-prone areas. Int. J. Disaster Risk Sci. 12, 805–820 (2021).

Jaiswal, K., Wald, D. J., Earle, P. S., Porter, K. A. & Hearne, M. in Human Casualties in Earthquakes: Progress in Modelling and Mitigation 83–94 (Springer, 2010).

Li, M., Zou, Z., Xu, G. & Shi, P. in World Atlas of Natural Disaster Risk IHDP/Future Earth-Integrated Risk Governance Project Series (eds Shi, P. & Kasperson, R.) 25–39 (Springer, 2015).

Subnational HDI v.7 (Global Data Lab, accessed 13 April 2023); https://globaldatalab.org/shdi/download/shdi/

World Risk Poll Data (Lloyd's Register Foundation, 2024); https://www.lrfoundation.org.uk/wrp/world-risk-poll-data

Kutir, C., Agblorti, S. K. & Campion, B. B. Migration and estuarine land use/land cover (LULC) change along Ghana’s coast. Reg. Stud. Mar. Sci. 54, 102488 (2022).

Anav, A. et al. Spatiotemporal patterns of terrestrial gross primary production: a review. Rev. Geophys. 53, 785–818 (2015).

Bi, W. et al. A global 0.05 dataset for gross primary production of sunlit and shaded vegetation canopies from 1992 to 2020. Sci. Data 9, 213 (2022).

Chen, J. et al. Global 1 km × 1 km gridded revised real gross domestic product and electricity consumption during 1992–2019 based on calibrated nighttime light data. Sci. Data 9, 202 (2022).

IPCC Special Report on Managing the Risks of Extreme Events and Disasters to Advance Climate Change Adaptation (eds Field, C. B. et al.) (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2012).

Gong, P. et al. Annual maps of global artificial impervious area (GAIA) between 1985 and 2018. Remote Sens. Environ. 236, 111510 (2020).

Xu, L. Peplication Data for “Global coastal human settlement retreat driven by vulnerability to coastal climate hazards”. Harvard Dataverse https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/OWYNB0 (2024).

Xu, L. & Yang, X. Code for “Global coastal human settlement retreat driven by vulnerability to coastal climate hazards”. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.16757827 (2025).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (42007418, 42377168, T2350710802 and U2039202), the International Innovation Cooperation Project of Department of Science and Technology of Sichuan Province (2024YFHZ0241), the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2023YFE0121900), the Shenzhen Science and Technology Innovation Commission Project (GJHZ20210705141805017 and K23405006), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (SK2024-18), the Sichuan International Science and Technology Cooperation Base: International Joint Research Center for Multi-Hazard Resilience of Energy Infrastructure, the Center for Computational Science and Engineering at Southern University of Science and Technology, and Tsinghua University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.X., X.W. and B.D. conceived and designed the study. L.X. and X.Y. collected data and performed the analysis. W.P. contributed analysis tools. L.X. drafted the manuscript, and X.W., D.C., D.S., A.V.P., S.D., B.D. and K.S.P. revised the manuscript. All authors contributed to the interpretation of the results.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Climate Change thanks Joyce Chen, Song Gao and Xuecao Li for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Extended Data Fig. 1 Time series of the proximity of human settlements to coastlines by continent from 1992 to 2019.

The solid lines represent linear least-squares fits; shaded bands indicate 75% confidence intervals.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Time series of the proximity of human settlements to coastlines by income group from 1992 to 2019.

The solid lines represent linear least-squares fits; shaded bands indicate 75% confidence intervals.

Extended Data Fig. 3

Settlement movement patterns across different income groups for the 1990s (a), 2000s (b), and 2010s (c), respectively.

Extended Data Fig. 4 Top 20 countries and sub-regions with with fastest paces of retreat.

(a) Top 20 countries with fastest paces of retreat. Dots indicate individual coastal sub-national regions (n = 57 overall; n varies by country). Box hinges indicate the upper and lower quartiles; center lines indicate the median value; crosses indicate the mean value; whiskers extend to the minimum and maximum values. (b) Top 20 coastal sub-national regions with fastest paces of retreat.

Extended Data Fig. 5 Top 20 countries and sub-regions with with fastest paces of approach.

(a) Top 20 countries with fastest paces of movement toward their coastlines. Dots indicate individual coastal sub-national regions (n = 50 overall; n varies by country). Box hinges indicate the upper and lower quartiles; center lines indicate the median value; crosses indicate the mean value; whiskers extend to the minimum and maximum values. (b) Top 20 coastal sub-national regions with fastest paces of movement toward their coastlines.

Extended Data Fig. 6

Adaptation performance and gaps in regions with stable settlement distance in low- and high-income countries.

Extended Data Fig. 7 Settlement proximity and movement patterns from ISA, and their comparison with NTL-based results.

(a) Average proximity of human settlements to coastlines from 1992 to 2019 based on ISA data; (b) Comparison of proximity values derived from ISA and NTL-based physical extents; (c) Coastal settlement movement patterns identified using ISA data; (d) Distribution of movement categories from ISA data and comparison with those derived from the NTL-based physical extents. Basemap in a,c from Natural Earth (https://www.naturalearthdata.com/).

Extended Data Fig. 8 Consistency of movement categories derived from NTL-based physical extents and ISA data.

(a) Spatial distribution of consistency in movement categories between the two datasets; (b) Overall agreement of movement classifications between NTL-based physical extents and ISA-derived; (c) Variation in consistency across sub-national regions with different income levels; (d) Transfer matrix illustrating the correspondence of movement categories between results derived from NTL-based physical extents and ISA data, showing how each category identified using NTL-based physical extents aligns with the same or different categories in ISA; (e) Statistics showing the consistency between the two datasets in identifying specific movement categories. “Consistent” refers to cases where the same movement category was identified using both the NTL-based physical extents and ISA data. Basemap in a from Natural Earth (https://www.naturalearthdata.com/).

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figs. 1–14 and Tables 1–3.

Source data

Source Data Fig. 1

Statistical source data.

Source Data Fig. 2

Statistical source data.

Source Data Fig. 3

Statistical source data.

Source Data Fig. 4

Statistical source data.

Source Data Fig. 5

Statistical source data.

Source Data Fig. 6

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 1

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 2

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 3

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 4

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 5

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 6

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 7

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 8

Statistical source data.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Xu, L., Yang, X., Chen, D. et al. Global coastal human settlement retreat driven by vulnerability to coastal climate hazards. Nat. Clim. Chang. 15, 1060–1070 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-025-02435-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-025-02435-6