Abstract

Increased water temperatures under climate change will probably cause decreases in dissolved oxygen and an associated increase in the number of days with hypoxia. This could have major consequences for freshwater ecosystems, but the extent of this threat remains unclear. Here we analyse trends in dissolved oxygen concentrations and days with stress and hypoxia in rivers worldwide between the periods 1980–2019 and 2020–2100 under global change. To achieve this, we train a hybrid process-based and machine learning model on approximately 2.6 million observations of dissolved oxygen, and we apply this model under both past and future conditions globally. The model projects significant decreasing trends in dissolved oxygen in most of the world’s rivers, resulting in on average 8.8 ± 2.3 more hypoxia days per decade globally between the years 2020 and 2100, and indicating a potentially major threat to freshwater ecosystems worldwide.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$32.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $21.58 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

Daily DO output from DynQual_Random Forest over the periods 1980–2019 and 2020–2100 is available via Yoda at https://doi.org/10.24416/UU01-0QHX53 (ref. 63). DO monitoring data are available via Zenodo at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15308434 (ref. 64).

Code availability

Python scripts associated with the analysis of this study and development of the hybrid DynQual_Random Forest model are available via Zenodo at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.13329996 (ref. 65) and GitHub at https://github.com/SustainableWaterSystems/DYNQUAL/tree/feature/dissolved_oxygen.

References

Zhi, W., Klingler, C., Liu, J. & Li, L. Widespread deoxygenation in warming rivers. Nat. Clim. Change 13, 1105–1113 (2023).

Jane, S. F. et al. Widespread deoxygenation of temperate lakes. Nature 594, 66–70 (2021).

Chapra, S. C., Camacho, L. A. & McBride, G. B. Impact of global warming on dissolved oxygen and BOD assimilative capacity of the world’s rivers: modeling analysis. Water 13, 2408 (2021).

Rose, K. C. et al. Aquatic deoxygenation as a planetary boundary and key regulator of Earth system stability. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 8, 1400–1406 (2024).

Saari, G. N., Wang, Z. & Brooks, B. W. Revisiting inland hypoxia: diverse exceedances of dissolved oxygen thresholds for freshwater aquatic life. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 25, 3139–3150 (2018).

Capon, S. J., Stewart-Koster, B. & Bunn, S. E. Future of freshwater ecosystems in a 1.5 °C warmer world. Front. Environ. Sci. 9, 784642 (2021).

Kannel, P. R., Kanel, S. R., Lee, S., Lee, Y. S. & Gan, T. Y. A review of public domain water quality models for simulating dissolved oxygen in rivers and streams. Environ. Model. Assess. 16, 183–204 (2011).

Piatka, D. R. et al. Dissolved oxygen isotope modelling refines metabolic state estimates of stream ecosystems with different land use background. Sci. Rep. 12, 10204 (2022).

Diamond, J. S. et al. Stream network variation in dissolved oxygen: metabolism proxies and biogeochemical controls. Ecol. Indic. 131, 108233 (2021).

Graham, D. J., Bierkens, M. F. P. & van Vliet, M. T. H. Impacts of droughts and heatwaves on river water quality worldwide. J. Hydrol. 629, 130590 (2024).

Singh, G. G., Sajid, Z. & Mather, C. Quantitative analysis of mass mortality events in salmon aquaculture shows increasing scale of fish loss events around the world. Sci. Rep. 14, 3763 (2024).

Till, A., Rypel, A. L., Bray, A. & Fey, S. B. Fish die-offs are concurrent with thermal extremes in north temperate lakes. Nat. Clim. Change 9, 637–641 (2019).

Kragh, T., Martinsen, K. T., Kristensen, E. & Sand-Jensen, K. From drought to flood: sudden carbon inflow causes whole-lake anoxia and massive fish kill in a large shallow lake. Sci. Total Environ. 739, 140072 (2020).

Verberk, W. C. E. P., Bilton, D. T., Calos, P. & Spicer, J. I. Oxygen supply in aquatic ectotherms: partial pressure and solubility together explain biodiversity and size patterns. Ecology 92, 1565–1572 (2011).

Jutfelt, F. et al. ‘Aerobic scope protection’ reduces ectotherm growth under warming. Funct. Ecol. 35, 1397–1407 (2021).

Vaquer-Sunyer, R. & Duarte, C. M. Thresholds of hypoxia for marine biodiversity. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 105, 15452–15457 (2008).

Li, L. et al. River water quality shaped by land–river connectivity in a changing climate. Nat. Clim. Change 14, 225–237 (2024).

Tedesco, P. A. et al. A global database on freshwater fish species occurrence in drainage basins. Sci. Data 4, 170141 (2017).

Jones, E. R. et al. DynQual v1.0: a high-resolution global surface water quality model. Geosci. Model Dev. 16, 4481–4500 (2023).

Streeter, H. W. & Phelps, E. B. A Study of the Pollution and Natural Purification of the Ohio River US Public Health Service Bulletin 146 (US Public Health Service, 1925).

Tang, T. et al. Bridging global, basin and local-scale water quality modeling towards enhancing water quality management worldwide. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 36, 39–48 (2019).

van Vliet, M. T. et al. Model inter-comparison design for large-scale water quality models. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 36, 59–67 (2019).

Cho, K. H., Pachepsky, Y., Ligaray, M., Kwon, Y. & Kim, K. H. Data assimilation in surface water quality modeling: a review. Water Res. 186, 116307 (2020).

Zhi, W., Appling, A. P., Golden, H. E., Podgorski, J. & Li, L. Deep learning for water quality. Nat. Water 2, 228–241 (2024).

Desbureaux, S. et al. Mapping global hotspots and trends of water quality (1992–2010): a data driven approach. Environ. Res. Lett. 17, 114048 (2022).

Tiyasha, T. T. M. & Yaseen, Z. M. A survey on river water quality modelling using artificial intelligence models: 2000–2020. J. Hydrol. 585, 124670 (2020).

Booker, D. J. & Whitehead, A. L. Inside or outside: quantifying extrapolation across river networks. Water Resour. Res. 54, 6983–7003 (2018).

Ahmed, M. H. & Lin, L. S. Dissolved oxygen concentration predictions for running waters with different land use land cover using a quantile regression forest machine learning technique. J. Hydrol. 597, 126213 (2021).

van Vliet, M. T. H. et al. Global river water quality under climate change and hydroclimatic extremes. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 4, 687–702 (2023).

Lange, S. & Büchner, M. ISIMIP3b bias-adjusted atmospheric climate input data, version 1.1. ISIMIP Repository https://doi.org/10.48364/ISIMIP.842396.1 (2021).

Jones, E. R. et al. Sub-Saharan Africa will increasingly become the dominant hotspot of surface water pollution. Nat. Water 1, 602–613 (2023).

Riahi, K. et al. The Shared Socioeconomic Pathways and their energy, land use, and greenhouse gas emissions implications: an overview. Glob. Environ. Change 42, 153–168 (2017).

Fujimori, S. et al. SSP3: AIM implementation of Shared Socioeconomic Pathways. Glob. Environ. Change 42, 268–283 (2017).

Zhi, W., Ouyang, W., Shen, C. & Li, L. Temperature outweighs light and flow as the predominant driver of dissolved oxygen in US rivers. Nat. Water 1, 249–260 (2023).

Ali, B., Mishra, A. & Author, C. Effects of dissolved oxygen concentration on freshwater fish: a review. Int. J. Fish. Aquat. Stud. 10, 113–127 (2022).

Pollock, M. S., Clarke, L. M. J. & Dubé, M. G. The effects of hypoxia on fishes: from ecological relevance to physiological effects. Environ. Rev. 15, 1–14 (2007).

Rosenfeld, J. & Lee, R. Thresholds for reduction in fish growth and consumption due to hypoxia: implications for water quality guidelines to protect aquatic life. Environ. Manag. 70, 431–447 (2022).

Hrycik, A. R., Almeida, L. Z. & Höök, T. O. Sub-lethal effects on fish provide insight into a biologically-relevant threshold of hypoxia. Oikos 126, 307–317 (2017).

Burleson, M. L., Wilhelm, D. R. & Smatresk, N. J. The influence of fish size size on the avoidance of hypoxia and oxygen selection by largemouth bass. J. Fish. Biol. 59, 1336–1349 (2001).

Mucha, S., Chapman, L. J. & Krahe, R. The weakly electric fish, Apteronotus albifrons, actively avoids experimentally induced hypoxia. J. Comp. Physiol. A 207, 369–379 (2021).

Wang, Z. et al. Hypoxia-induced physiological responses in fish: from organism to tissue to molecular levels. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 267, 115609 (2023).

Tripathy, K. P., Mukherjee, S., Mishra, A. K., Mann, M. E. & Park Williams, A. Climate change will accelerate the high-end risk of compound drought and heatwave events. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 120, e2219825120 (2023).

Donat, M. G., Lowry, A. L., Alexander, L. V., O’Gorman, P. A. & Maher, N. More extreme precipitation in the world’s dry and wet regions. Nat. Clim. Change 2016, 508–513 (2016).

Parmesan, C. et al. in Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaption and Vulnerability (eds Pörtner, H.-O. et al.) 197–377 (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2022).

Jones, E. R. et al. Current wastewater treatment targets are insufficient to protect surface water quality. Commun. Earth Environ. 3, 221 (2022).

Sutanudjaja, E. H. et al. PCR-GLOBWB 2: a 5 arcmin global hydrological and water resources model. Geosci. Model Dev. 11, 2429–2453 (2018).

Rice, E. W., Baird, R. B. & Eaton, A. D. Standard Methods for the Examination of Water and Wastewater (American Public Health Association, 2017).

O’Connor, D. J. & Dobbins, W. E. Mechanism of reaeration in natural streams. Trans. Am. Soc. Civ. Eng. 123, 641–684 (1958).

van Vliet, M. T. H. et al. Global water scarcity including surface water quality and expansions of clean water technologies. Environ. Res. Lett. 16, 024020 (2021).

Wen, Y., Schoups, G. & Van De Giesen, N. Organic pollution of rivers: combined threats of urbanization, livestock farming and global climate change. Sci. Rep. 7, 43289 (2017).

McIntyre, N. R., Wagener, T., Wheater, H. S. & Yu, Z. S. Uncertainty and risk in water quality modelling and management. J. Hydroinformatics 5, 259–274 (2003).

Lindenschmidt, K. E., Fleischbein, K. & Baborowski, M. Structural uncertainty in a river water quality modelling system. Ecol. Model. 204, 289–300 (2007).

Hartmann, J., Lauerwald, R. & Moosdorf, N. A brief overview of the global river chemistry database, GLORICH. Proc. Earth Planet. Sci. 10, 23–27 (2014).

United Nations Environment Programme. GEMStat Database of the Global Environment Monitoring System for Freshwater (GEMS/Water) Programme (International Centre for Water Resources and Global Change, accessed 1 February 2024); available upon request from GEMS/Water Data Centre: https://gemstat.org

Waterbase—Water Quality ICM (European Environment Agency, accessed 1 February 2024); https://www.eea.europa.eu/data-and-maps/data/waterbase-water-quality-icm-2

Water Quality Portal (National Water Quality Monitoring Council, accessed 1 February 2024); https://doi.org/10.5066/P9QRKUVJ

National Long-Term Water Quality Monitoring Data (ECCC, accessed 1 February 2024); https://data-donnees.az.ec.gc.ca/data/substances/monitor/national-long-term-water-quality-monitoring-data/

Research Quality Information Services Data and Reports (Department of Water and Sanitation, South Africa, accessed 1 February 2024); https://www.dws.gov.za/iwqs/report.aspx

Hydro Web Portal (National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research, New Zealand, accessed 1 February 2024); https://hydrowebportal.niwa.co.nz/

Lehner, B. & Grill, G. Global river hydrography and network routing: baseline data and new approaches to study the world’s large river systems. Hydrol. Process. 27, 2171–2186 (2013).

Cucchi, M. et al. WFDE5: bias-adjusted ERA5 reanalysis data for impact studies. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 12, 2097–2120 (2020).

Lange, S. et al. WFDE5 over land merged with ERA5 over the ocean, W5E5 v2.0. ISIMIP Repository https://doi.org/10.48364/ISIMIP.342217 (2021).

Graham, D. Dissolved oxygen hybrid simulations. Yoda https://doi.org/10.24416/UU01-0QHX53 (2025).

Graham, D. Dissolved oxygen monitoring data. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15308434 (2025).

Graham, D. Dissolved oxygen python analysis code. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.13329996 (2024).

Acknowledgements

We thank J. Wang (Utrecht University) for their inputs related to biogeochemistry. We would like to thank A. Schipper (Radboud University and PBL Netherlands Environmental Assessment Agency) for providing valuable feedback on this study. The calculations of the study were computed on the Dutch national supercomputer Snellius with the support of SURFsara. D.J.G. and M.T.H.v.V. were financially supported by the Netherlands Scientific Organisation VIDI grant no. VI.Vidi.193.019. In addition, M.T.H.v.V. acknowledges funding from the European Research Council B-WEX grant no. 101039426.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

D.J.G. performed the model simulations and data analyses and wrote the original drafts of the paper and methods. D.J.G., M.T.H.v.V. and M.F.P.B. conceptualized the study. M.T.H.v.V. and M.F.P.B. supervised the project and contributed to the writing. E.H.S. and E.R.J. assisted in the project. All authors contributed to editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Climate Change thanks Li Li, Robert Schwefel and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

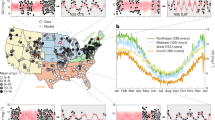

Extended Data Fig. 1 Process-based model evaluation (DynQual).

(a-e) process-based simulations of dissolved oxygen (DO) from DynQual v1.1 (blue) compared with monitoring data (black) for five different stations across North America, Europe, New Zealand, Asia and South America. (f-g) Model validation of DynQual for different classes of water temperature (Tw) and river discharge (Q). Grey denotes observation data. Boxplots: median, first quartile (Q1), third quartile (Q3), Q1 − 1.5IQR, Q3 + 1.5IQR where IQR is Interquartile range.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Basin-scale validation of DynQual_Random Forest and DynQual.

(a) Water quality monitoring stations with dissolved oxygen concentration measurements available based on 7 water quality datasets53,54,55,56,57,58,59. (b) normalised Root-Mean-Squared-Error (nRMSE) of DynQual_Random Forest using all available dissolved oxygen concentration data. Note: median nRMSEs are estimated per river basin based on HydroSHEDs level 4 (c) nRMSE histograms: DynQual_Random Forest (red) and DynQual (blue). (d) nRMSEs of DynQual: all data. (e) nRMSEs of DynQual_Random Forest using dissolved oxygen concentration data below the 10th percentiles. (f) nRMSE histograms: data below 10th percentiles. (g) nRMSEs of DynQual: dissolved oxygen data below the 10th percentiles (h) Average nRMSE of DynQual_Random Forest for each year between 1980–2019. (i) Percentage biases (PBIAS) of DynQual_Random Forest (red) and DynQual (blue): all data. (j) Average nRMSE of DynQual for each year between 1980–2019. River basin shapefiles in b, d, e and g adapted with permission from ref. 60, Wiley.

Extended Data Fig. 3 Station level validation of DynQual_Random Forest and DynQual.

(a) Spatial patterns with Means Errors (ME) of DynQual_Random Forest (b) Root-Mean-Squared-Errors (RMSE) of DynQual_Random Forest. (c) ME of DynQual (d) RMSE of DynQual for dissolved oxygen monitoring stations globally. (e-h) Boxplots with dissolved oxygen (DO) concentrations for stress days (< 5 mg/l) and hypoxia days (DO data < 3 mg/l) for DynQual_Random Forest and DynQual. Boxplots: median, first quartile (Q1), third quartile (Q3), Q1 − 1.5IQR, Q3 + 1.5IQR where IQR is Interquartile range.

Extended Data Fig. 4 Regional and local validation of DynQual_Random Forest and DynQual.

(a) Median value of the Root Mean Squared Error, normalised by the mean (nRMSE), for each region and three month period (Jan-March, April-June, July-Sept, Oct-Dec) for the process-based model DynQual (b) median nRMSE value for each region and three-month period for the hybrid DynQual_Random Forest model (c) boxplots comparing the observed dissolved oxygen concentrations (grey) during periods of hypoxia (DO < 3 mg/l) with the simulations from DynQual_Random Forest (red) and DynQual (blue). Boxplots: median, first quartile (Q1), third quartile (Q3), Q1 − 1.5IQR, Q3 + 1.5IQR where IQR is Interquartile range. (d-g) Time-series of daily DO concentrations simulated by the hybrid DynQual_Random Forest model for four stations across Asia, North America, Australia/New Zealand and South America compared to monitoring data (black).

Extended Data Fig. 5 Further validation metrics of DynQual_Random Forest and DynQual.

(a) Median in Root-Mean-Squared-Errors (RMSEs) per river basin for DynQual_Random Forest (b) RMSEs for DynQual (blue) and DynQual_Random Forest (red) (c) median RMSEs per river basin for DynQual (d) lower 10th percentiles of dissolved oxygen (DO) data: median RMSEs per basin for DynQual_Random Forest (e) RMSEs for DynQual and DynQual_Random Forest (DO data < 10th percentiles) (f) median RMSEs for DynQual (DO data < 10th percentiles) (g) mean annual RMSE values (DynQual_Random Forest) (h) Mean absolute errors (MAE) DynQual and DynQual_Random Forest (i) Mean annual RMSE values for DynQual (j) Frequency of stress days (DO < 5 mg/l) simulated and observed (k) Frequency of hypoxia days (DO < 3 mg/l) simulated and observed. River basin shapefiles in a, c, d and f adapted with permission from ref. 60, Wiley.

Extended Data Fig. 6 Hydro-climatic conditions during training, testing and simulating at the global level.

(a-d) Statistical distributions of water temperature (Tw) and river discharge (Q) during 1980-2019 and 2020-2100. CDF: cumulative distribution function. (e-f) Model validation of DynQual_Random Forest and DynQual during periods of high water temperatures (Tw > 30 °C) and low discharge (Q < 30m3/s). Boxplots: median, first quartile (Q1), third quartile (Q3), Q1 − 1.5IQR, Q3 + 1.5IQR where IQR is Interquartile range.

Extended Data Fig. 7 Global trends in hydro-climatic variables, stress and hypoxia 1980-2019.

(a) Average trend in water temperature over the period 1980-2019. (b) Average trend in river discharge over the period 1980-2019. (c) Average trend in biochemical oxygen demand (BOD) concentration over the period 1980-2019. (d) Average absolute trend in the number of stress days (DO < 5 mg/l) over the period 1980-2019 using DynQual_Random Forest (e) Average absolute trend in the number of hypoxia days (DO < 3 mg/l) over the period 1980-2019 using DynQual_Random Forest. Grey denotes mean discharge < 10m3/s. Basemaps adapted from ref. 19 under a Creative Commons license CC BY 4.0.

Extended Data Fig. 8 Future trends in hydro-climatic variables 2020-2100.

(a) Average trend in water temperature over the period 2020-2100 based on five Global Climate Models (GCMs) for SSP3-RCP7.0 scenario. (b) Average trend in river discharge over the period 2020-2100 based on five GCMs. (c) Average trend in biochemical oxygen demand (BOD) concentration over 2020-2100 based on five GCMs. Grey denotes mean discharge < 10m3/s. Basemaps adapted from ref. 19 under a Creative Commons license CC BY 4.0.

Extended Data Fig. 9 Future trends in stress and hypoxia 2020-2100.

(a) Average absolute trend in the number of stress days (DO < 5 mg/l) over 2020-2100 based on five Global Climate Models (GCMs) for SSP3-RCP7.0 scenario using DynQual_Random Forest. (b) Average absolute trend in the number of hypoxia days (DO < 3 mg/l) over 2020-2100 based on five GCMs using DynQual_Random Forest. Grey denotes mean discharge < 10m3/s. Basemaps adapted from ref. 19 under a Creative Commons license CC BY 4.0.

Extended Data Fig. 10 Exposure of fish species to hypoxia.

(a) Freshwater fish species richness (SR) distribution (data from ref. 18). (b) Average trends in the number of freshwater fish species exposed to hypoxia per decade from 2020 to 2100 based on five Global Climate Models (GCMs) for SSP3-RCP7.0 scenario and using DynQual_Random Forest (percentage change) (c) Time-series of the total number of fish species exposed to hypoxia (DO < 2 mg/l) during 2020-2100 with the ensemble mean (thick line) and uncertainty bounds (±− standard deviation) of the 5 GCMs (DynQual_Random Forest) (d) Time-series of the total number of fish species exposed to hypoxia (DO < 3 mg/l) during 2020-2100 with the ensemble mean (thick line) and uncertainty bounds of the 5 GCMs (±− standard deviation) (DynQual_Random Forest). Panel a adapted with permission from ref. 18 under a Creative Commons license CC-BY 4.0. Basemap in b adapted from ref. 19 under a Creative Commons license CC BY 4.0.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Graham, D.J., Bierkens, M.F.P., Jones, E.R. et al. Climate change drives low dissolved oxygen and increased hypoxia rates in rivers worldwide. Nat. Clim. Chang. 15, 1348–1354 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-025-02483-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-025-02483-y