Abstract

Multiple climate-related stressors affect the ocean, including warming, acidification, deoxygenation and variations in salinity, with profound effects on Earth system cycles, marine ecosystems and human well-being. Nevertheless, a global perspective on the combined impacts of these changes on both surface and subsurface ocean conditions remains unclear. Here, applying a time-of-emergence methodology to observed physical and biogeochemical variables, collectively referred to as compound climatic impact-drivers, we show individual and compound ocean state changes have become increasingly prominent globally over the past 60 years. In particular, observations show the simultaneous emergence of compound climatic impact-drivers in regions spanning the subtropical and tropical Atlantic, the subtropical Pacific, the Arabian Sea and the Mediterranean Sea. We highlight extensive exposure of different ocean layers to compound emergence, characterized by significant intensity, duration and magnitude. These results provide a comprehensive framework and perspective to illustrate the ocean’s vulnerability to pervasive and interconnected changes in a warming climate.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

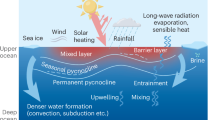

The ocean is vulnerable to a wide range of environmental stressors in a warming climate1,2, commonly referred to as ‘climatic impact-drivers’ (CIDs)3,4, which include phenomena such as surface and subsurface ocean warming, salinity variations, acidification, deoxygenation and other changes in relevant biogeochemical variables5. The evolving impacts of these CIDs on marine species, habitats and ecosystems, and the resulting biological responses6, pose prominent threats to the ocean’s overall health and resilience7.

Previous studies have examined the emergence of persistent shifts in several individual CIDs in the context of increasing anthropogenic greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions8,9,10,11. Simultaneous changes in these CIDs potentially amplify persistent pressures on marine life. However, previous efforts have been limited to a subset of individual CIDs9,10,12, focused on compound extreme events13,14, limited their scope to sea surface conditions or specific ocean layers11,13,15,16, or relied exclusively on model-derived data11,16. There is thus an urgent need for a comprehensive global investigation of simultaneous changes based on direct observations in multiple CIDs, hereafter referred to as ‘compound CIDs’.

Of particular relevance is which regions have already experienced substantial impacts from prolonged compound CIDs from the surface to the deep ocean. The temporal and spatial dynamics (that is, when and where), as well as the mechanisms underlying such changes (that is, how), are also poorly understood. Here we focus on the concurrent emergence of persistent changes (spanning more than 25 years, that is, long-term change perspective) by developing a methodology and framework to delineate regions that are profoundly affected by prolonged and substantial concomitant shifts in compound CIDs, identifying the timing and mechanisms underlying these shifts. Specifically, we address four key aspects: (1) the definition of compound CIDs, which denote simultaneous changes in multiple CIDs; (2) the determination of whether compound CIDs have emerged in the surface and subsurface oceanic realms as a consequence of short-term oceanic variability over the past six decades; (3) the assessment of the duration, intensity and magnitude of emergence of long-term compound CIDs; and (4) the evaluation of where and how severely the ocean environment is exposed to the emergence of long-term compound CIDs. Our analysis is based on various observational datasets and includes assessments of the persistent changes in individual CIDs and their collective emergence throughout the oceanic domain.

The compound CIDs framework

Literature on the concurrent change in the ocean climate system uses many terms interchangeably, such as multiple stressors3,16,17, (multi-)hazards18,19 and compound events13,20. The terms ‘multiple stressors’ and ‘(multi-)hazards’ refer mainly to adverse effects that deviate from the norm. The term ‘compound events’ is often associated with extreme events14,21. To differentiate from these terminologies, we use ‘compound CIDs’ to represent the simultaneous and persistent emergence of multiple CIDs that may have either positive or negative impacts4,6.

In this assessment framework, we use the time of emergence (ToE)10 to detect long-term changes in compound CIDs under warming. We first identify when and where the signal of an individual CID has emerged from the noise level before 2023 (see the figure in Box 1 and Methods). The long-term change (that is, signal) is quantified by applying a 25-year LOWESS filter22 to the global mean time series. The background variability (that is, noise) is quantified as the short-term (<25 years) variability of the local time series. The ToE is then defined as the first year in which the absolute value of the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) exceeds 1 and never falls back to the noise level (also testing the impact with the |SNR| > 2; see Methods for details). On the basis of the ToE for individual CIDs, we then define regions where multiple CIDs emerge simultaneously and refer to them as ‘double emergence’ and ‘triple emergence’, following the approach that the ToE of more than one CID can be detected if the signal of these CIDs has already emerged (see the figure in Box 1).

The categories of intensity, duration and magnitude of emergence are then defined by using a statistical distribution approach to analyse how strong, how long and how fast the signal has changed since its emergence (Box 1). Finally, these categories are used to understand where and how the ocean environment is exposed (different categories: high, medium, low) to long-term climate state changes in compound CIDs (see the figure in Box 1). On the basis of the proposed framework, we will analyse the changes from the ocean surface to the bottom of the mesopelagic zone (0–1,000 m) for four selected CIDs: ocean temperature (T), salinity (S), dissolved oxygen (DO) and surface pH in this study (Extended Data Table 1).

Time of emergence of compound CIDs

The ToE has been widely used to detect long-term changes in CIDs23,24, stressors25 and climate hazards26, and our analysis shows that different CIDs are associated with different timescales. For example, temperature and dissolved oxygen have a typical shorter emergence time than salinity to achieve the same global area coverage of emergence, while surface pH is the shortest (Fig. 1a,b), consistent with a previous study11. Further, we show that a large fraction of the global ocean is exposed to the emergence of both single and compound CIDs before 2023 (relative to the 1960–1989 baseline). In particular, almost the entire global ocean surface (~100%) is exposed to a decrease in pH emerging from the noise since 1995 (relative to the 1985–1989 baseline). This is attributed mainly to the continuous and increasing emission of anthropogenic carbon dioxide, which induces a net positive flux of CO2 from the atmosphere to the ocean15. This result is consistent with previous studies15 and is robust among different products used (Extended Data Fig. 1).

a, Surface. b, Epipelagic zone (0–200 m). c, Mesopelagic zone (200–1,000 m). d, The same as a but for the global percentage of emergence in the year 2023 as a function of depth from 0 to 1,000 m. Here an |SNR| > 1 threshold is used to calculate the ToE, corresponding to an ~67% confidence level. The shaded area represents the data uncertainty (95% confidence interval, accounting for instrumental uncertainty, sampling/mapping uncertainty and uncertainty due to (multi-)decadal variability in the quantification of the ‘signal’ and baseline choice (Methods). The percentage is derived from the ratio of the emergence area to the global ocean area. The reference period (baseline) is 1960–1989 for temperature, salinity and dissolved oxygen, and 1985–1989 for surface pH.

Long-term changes in other individual CIDs considered here (T, S and DO) have emerged since the early 1990s in about 20–60% of the global ocean area relative to the 1960–1989 baseline, for both the epipelagic and mesopelagic zones (Fig. 1b,c and Extended Data Figs. 2–4). Local significant ocean warming emergence (Extended Data Fig. 2) is driven primarily by the enhanced radiative forcing associated with the increasing atmospheric concentrations of GHGs27,28, consistent with the robust observed acceleration of ocean heating since the 1960s29. Changes in salinity patterns (for example, salinization in the Atlantic and Indian oceans and freshening in the Pacific Ocean; Extended Data Fig. 3 and ref. 30) are driven by the intensification of the global hydrological cycle, often described as a ‘wet-get-wetter’ and ‘dry-get-drier’ paradigm30,31,32. While salinity is decreasing in most ocean basins, increases in salinity in the Atlantic Ocean and the Mediterranean Sea are discussed in the context of increasing atmospheric transport of fresh water from these regions33. In general, local temperature and salinity changes in the ocean can result from perturbed air–sea heat and freshwater fluxes and from the redistribution of the temperature and salinity fields due to the transport of ocean properties and circulation changes34. In addition, ocean deoxygenation (Extended Data Fig. 4) could be attributed to ocean warming via the causal relationship between temperature and oxygen solubility (negative correlation), superimposed on increasing warming-induced oxygen consumption in the upper layer6,35. Previous studies on long-term trend analysis of individual CIDs (mainly for surface layer) also show a similar spatial and temporal pattern36,37,38,39. These single-emergence patterns are not sensitive to the choices of observational-based data products and are consistent with previous estimates (see the discussions of ‘Robustness of the results on the choice of observational data products’ in Methods and Extended Data Figs. 5–7).

In the case of double emergence (associated T with S or T with DO changes), the percentage is about 7% (~3–10%) from the surface layer down to about 32% (~13–48%) at the bottom of the mesopelagic zone since the 2000s (with 95% data uncertainty range, using |SNR| > 1 threshold; Methods). In addition, the global percentage of triple emergence shows an increase at depth along with a decreasing noise magnitude, from about 8% (~6–11%) in the top of the epipelagic zone and down to 11% (7–16%) at the bottom of the mesopelagic zone (mainly for warming coupled with salinity change and deoxygenation; Fig. 1b–d). Here the long-term change of ocean warning in combination with salinity change, freshening and deoxygenation can be discussed in the context of different types of multivariate relationships between these CIDs (Box 1 and Fig. 4). The joint relationship between near-surface temperature and salinity anomalies can induce changes in the ocean density, affect upper-ocean stratification, modify the mixed-layer depth and in turn trigger changes in ocean circulation1,37,40. Ocean processes such as water mass subduction, mixing, advection and ventilation are important conduits for propagating long-term trend signals from the surface down to the subsurface ocean31. In addition, concurrent changes in temperature and salinity can increase oxygen consumption and weaken the ventilation and subduction of oxygen from the surface to the thermocline35,41. The combination of these two factors suggests a composite relationship to the observed subsurface deoxygenation.

The observed long-term emergence of compound CIDs over the past 64 years also reveals different regional spatial patterns (Fig. 2). Large-scale significant compound emergence is observed in the subtropical North Atlantic, the subtropical Pacific, the tropical Atlantic, the Mediterranean Sea and the northern Indian Ocean. Some of these emerged before the 2000s, others after. Among these regions, in the epipelagic zone (Fig. 2b), the Mediterranean Sea shows the highest percentage of significant double and triple emergence, reaching up to ~96%. This is followed by the subtropical North Atlantic (~93% within ~20° N–40° N) and the tropical Atlantic (~71% within ~20° S–20° N). In these regions, certain specific dynamical regimes dominate, such as coastal upwelling zones42, tropical oxygen minimum zones (OMZs)37,43, basin-scale to global-scale circulation systems (for example, the meridional overturning circulation44,45) and regions of transport convergence46.

a, Surface layer (0 m). b, Epipelagic (0–200 m) zone. c, Mesopelagic (200–1,000 m) zone. The white colour indicates no emergence before 2023. Here an |SNR| > 1 threshold is used to calculate ToE (~67% confidence level), but regions where |SNR| > 2 (~95% confidence level) are additionally marked with red dots. White indicates no emergence or insignificant emergence before 2023, as defined by the 95% confidence interval of data uncertainty (see Extended Data Figs. 8 and 9 and Methods). Surface pH emergence (black slashes) is shown separately because of a different reference period. Polar regions (beyond 70° N and 60° S) are not included due to data limitations.

For example, North Atlantic warming27, deoxygenation35,41 and ‘salinity pile-up’47 are driven by enhanced air–sea exchange of heat, water and oxygen along with changing oceanic processes, stratification and inter-basin transport of water properties. These changes are known to be also influenced by climate modes, such as the North Atlantic Oscillation or the Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation27. In addition, changes in the warming-induced circulation variability and the thermohaline structure of water masses, superimposed by changes in the rate of nutrient supply, contribute to the deoxygenation in the eastern boundary upwelling zone and tropical Atlantic OMZs6, suggesting a composite relationship to the triple emergence of compound CIDs (see the terminology in Fig. 4). Double and triple emergences in the mesopelagic zone are observed in similar regions detected in the overlying layer, such as in the Pacific and North Atlantic subtropical gyres (Fig. 2c), which are characterized by deep-reaching (about 800 m) dynamical patterns48.

A large fraction of the North Indian Ocean (~58% within ~0–30° N) and the North Pacific Subtropical Gyre (~42% within ~23–40° N) in the mesopelagic zone are subject to significant compound emergence (Fig. 2c). In the Arabian Sea, triple emergence occurs in an enhanced evaporative region characterized by the changes of air–sea interactions, the overflow of warmer, high-salinity, oxygen-saturated water from the Red Sea and the Persian Gulf, monsoon-induced circulation changes, and the expansion and deepening of the OMZ of the Arabian Sea49,50,51,52,53. In addition, one of the possible factors influencing the observed double and triple emergences in the mesopelagic zone in the Bay of Bengal is the eastward inflow of high-salinity water from the Arabian Sea via the Summer Monsoon Current54,55.

Ocean exposure to the emergence of compound CIDs

To further explore how long, how strong and how fast compound CIDs emerge in the preceding five regions, three metrics (duration of emergence, intensity of emergence and magnitude of emergence) are defined on the basis of their probability density (see panel b of the figure in Box 1 and Supplementary Table 2). The spatial maps of the three emergence metrics are presented in the Supplementary Fig. 4 (see section D of Supplementary Information). High, medium and low exposure are then defined on the basis of the extent of the preceding three metrics (see panel c of the figure in Box 1 and Methods). In the subtropical central North Atlantic, there is a notable medium (high) exposure of double emergence to compound CIDs in the surface (epipelagic zone) related primarily to warming and salinization (Fig. 3a,b). In addition, the epipelagic zone and mesopelagic zone of most of the Mediterranean Sea, the North Atlantic subtropical gyre and its western boundary current (for example, the Gulf Stream) show high exposure to the triple emergence (Fig. 3b,c). Similar characteristics are observed in the mesopelagic zone for the tropical Atlantic OMZ, the Arabian Sea and most of the North Atlantic subtropical gyre, represented mainly by long duration, high intensity and high magnitude of emergence (Fig. 3c). Our results show that a substantial fraction of the subsurface ocean (about 25% of the global ocean) is already significantly exposed (with medium to high exposure) to the emergence of more than two CIDs and is expected to continue to emerge in more regions according to projections3,56.

a, Surface layer (0 m). b, Epipelagic zone (0–200 m). c, Mesopelagic zone (200–1,000 m). Areas in white colour indicate low exposure to the emergence of compound CIDs. Exposure to surface pH emergence is shown separately from other CIDs because of the different reference period. Here the emergence results are adopted from Fig. 2 (|SNR| > 1 threshold), with regions where |SNR| > 2 marked with red dots.

This physical understanding of the ocean’s exposure to the double and triple emergence provides a global view of concurrent changes in compound CIDs and their multivariate relationships. Compound CIDs potentially involve nonlinear interactions that include joint, causal and composite relationships (Fig. 4 and Box 1). For example, the ocean’s exposure from the double emergence of warming coupled with salinity changes may jointly cause changes in ocean stratification40, density57 and circulation47 (joint relationship). At the same time, coupling with ocean deoxygenation (that is, the double emergence of warming and deoxygenation) could cause an expanding area of ‘dead zone’58 (causal relationship; Fig. 4). The combined interaction of double or triple emergence (that is, composite relationship) may indicate multiple nonlinear interaction pathways in the energy cycle27, hydrological cycle30 and biogeochemical cycle (for example, carbon cycle and oxygen cycle)15. Therefore, further research is needed to improve the understanding of the physical and biological processes in the regions highly exposed to compound CIDs, especially multivariate relationships (or multi-system interactions) in a complex climate system (for example, changes in ventilation, stratification, density and circulation).

Future perspectives

Our results indicate that a substantial portion of the global ocean, ranging from surface waters to the epipelagic and mesopelagic zones, has experienced moderate to substantial exposure to the emergence of long-term compound CIDs over the past six decades. This indicates a transition to a different ocean state in a warming climate. Therefore, it is important to quantify the level of the impact from climate change on observed compound effects. Here we provide some first indications by analysing the spatial distribution of long-term compound CIDs emergence coinciding with regions critical for natural carbon sequestration (Fig. 5a), global fishing activities (Fig. 5b) and recent international policy negotiations (Fig. 5c).

a, Mean total organic carbon export (mgC m−2 d−1) from ref. 59. b, Mean 2013–2020 total fishing effort (fishing hours per square kilometre) from ref. 60. c, Median fraction (%) of the high seas64 with the individual and compound CID emergences before 2023 across different layers. Error bars represent 95% data uncertainty range (definitions in Methods). The slashes, black dots and purple dots represent the areas of exposure (medium and high) to single, double and triple emergences in the epipelagic zone (0–200 m, corresponding to Fig. 3b), respectively.

The ocean’s biological carbon pump plays a critical role in regulating atmospheric CO2 levels through processes such as primary production, particle aggregation and sinking, remineralization, and sequestration59. Our data show that approximately 48.28%, 13.17% and 2.83% of the current global organic carbon export at 100 m depth originates from regions characterized by medium to high exposure to significant single, double and triple CID emergences, respectively (Fig. 5a). With respect to global fisheries, we show that approximately 51.47%, 14.33% and 3.01% of regions characterized by high fishing intensity (greater than 0.01 h km−2) are exposed to significant single, double and triple CID emergences, respectively. Notable affected regions include the eastern North Atlantic, Gulf Stream, Mediterranean Sea, Tropical Atlantic, Kuroshio, seas around small island countries in the South Pacific, and Atlantic Subtropical Gyre (Fig. 5b). While historical narratives have traditionally emphasized cultural and political factors in shaping fishing activities60, our results suggest a potential influence of compound climate change on the blue economy and on climate risk assessment within the fisheries or mariculture sectors61. We therefore advocate incorporating the aforementioned compound CIDs as multiparameter into biogeochemical or bioclimatic models (for example, species distribution model; climate envelope model). By accurately understanding the relationships among these parameters (Fig. 4) in the model, this approach can improve understanding of the biological carbon pump62 and ocean fisheries conditions63 for the past and future ocean changes, finally contributing to formulating reliable ocean adaptation strategies.

In addition, a substantial portion of the high seas, particularly the Biodiversity Beyond National Jurisdiction areas64, is already experiencing a double or triple emergence of compound CIDs, with the incidence increasing from the surface (~6%) to the mesopelagic zone (~38%; Fig. 5c). These findings support the establishment of large-scale marine protected areas within these ‘compound climate change hotspots’ and for guiding the implementation of environmental impact assessments in accordance with the adopted treaty64. The emergence of compound CIDs thus serves as an analysis framework, a science-policy interface tool and data/indicators to facilitate the integration of oceanic environmental change understanding with broader knowledge of the compound impacts on the ocean and human societies.

Due to the limited availability of observation-based products, only a finite number of CIDs at the global scale can currently be comprehensively assessed65. Facilitating data processing techniques and ensuring open access to data through the expansion of initiatives such as the Global Climate Observing System66 and the Global Ocean Observing System67 will enable the study of a broader range of long-term changes in CIDs across different components of the Earth system and in broader regions. This could include biogeochemical variables such as subsurface pH, dissolved inorganic carbon, [H+], \({p}_{{\mathrm{CO}}_{2}}\)(partial pressure of CO2), chlorophyll-a concentrations, primary production rates and nutrient concentrations in the ocean (for example, ref. 68). Furthermore, an analysis of Coupled Model Intercomparison Project Phase 6 (CMIP6) models indicates substantial uncertainty in representing the compound ToE patterns because of large spreads in model simulations of subsurface salinity and dissolved oxygen changes (Supplementary Figs. 5−7 versus Extended Data Figs. 2–4). Although we note that some models may reproduce similar ToE results compared with observations (for example, GFDL-CM4, BCC-CSM2-MR, FIO-ESM-2-0 and CMCC-ESM2), using model ensemble mean may not be the most effective tool for studying compound CIDs. Thus, caution is needed when relying solely on the model ensemble mean to project future risks. Consolidated efforts are essential to understand model biases and constrain future projections.

As the prevalence of long-term concurrent changes in compound CIDs has escalated in a warming climate, it is imperative to recognize the potential biological effects of exposure to these. Such effects could be synergistic, where the combined effect of multiple factors is greater than the sum of their individual effects6,69. Conversely, they may also exhibit antagonistic interactions, where the combined effect is less than the sum of the individual effects, or simply additive, where the combined effect is equal to the sum of the individual effects6,69. These dynamics have implications for the dynamics of deep-sea coral ecosystems70,71, phytoplankton72, zooplankton73, fishery catches74, aquatic woody plants75, invertebrates76, mammals77, marine biodiversity78 and so on (Fig. 4). These efforts are paramount to supporting initiatives such as ecosystem-based fisheries management79 and the blue economy80 for the ocean and improving frameworks for assessing ocean risk, especially in the context of compound risks, in various ocean sectors81 for policymakers and ocean management.

While we do not formally attribute these compound ocean state changes to specific anthropogenic forcing, feedbacks or internal variability, the additional CMIP6 experiments included here show that the significant emergences of compound CIDs are due largely to anthropogenic climate change (Supplementary Information section E). Furthermore, the current ToE estimation is very likely a conservative estimation from the global climate change perspective since the Industrial Revolution of the 1850s (Supplementary Information section F). Our conclusion is also supported by numerous previous studies that have discussed or attributed the long-term change in individual CIDs in the context of a warming climate (for example, temperature/ocean heat content27,29; salinity30,82; dissolved oxygen37,56,83; pH11,68). Further formal attribution studies to better isolate the forced response could improve the current estimation.

Compound long-term changes of CIDs will probably continue to evolve in a warming future as projected by climate model simulations56, with the high-exposure areas likely to continue to increase. The evolution of ocean climate, whether in causal, joint or composite interactions, is rapidly transforming oceanic physical and biogeochemical conditions to an interconnected changing ocean climate state. This complex transformation is gradually reshaping marine biodiversity78, and internal ocean processes, with potential changes in thermohaline circulation47, sea-level rise84, compound extremes events13 and so on. There are also socioeconomic impacts, with sectors such as fisheries and marine aquaculture likely to face increasing challenges (for example, Fig. 5b), highlighting the need for compound risk assessment associated with climate-related hazards81,85. For example, any change in the marine environment caused by the compound CIDs that exceeds an ecological threshold for organism survival may have irreversible consequences for the affected species86,87. In fact, it is unclear how these compound effects will evolve in the future under the background of a changing ocean state. Questions still need to be resolved in the next step to understand species-specific impacts of compound environmental changes88.

Methods

Datasets

In this study, we focus on the concurrent long-term changes of the following CIDs: ocean mean temperature (T), salinity (S), dissolved oxygen (DO) and surface pH. Extended Data Table 1 lists the observational data products used in this study. We selected these four CIDs concerning the assessments of the confidence levels, potential impacts on marine ecosystems and risk management in the Sixth Assessment Report of the IPCC4,6 (Supplementary Information section A), the identification and determination of robust CID categories in the open ocean associated with essential climate variables102 and the data availability (Supplementary Information section B).

For temperature, we use the Institutes of Atmospheric Physics (IAP, Chinese Academy of Sciences) monthly temperature global ocean gridded products (version 4) at 1° × 1° horizontal resolution for the upper 6,000 m with 119 standard depth levels from 1960 to 2023103. The strength of IAP temperature products has been discussed in previous publications, including the bias corrections for in situ temperature profile data (for example, XBT (expendable bathythermograph), MBT (mechanical bathythermograph) and Bottle104,105,106), an updated quality control method that accounts for the skewness of local variable distribution, topographic barriers and the shift of distribution due to climate change107, an ensemble optimal interpolation (EnOI) method to fill the data gaps with dynamical covariances that can minimize the sampling errors caused by changes in the temporal–spatial distribution of in situ observations108. In addition, this product uses the EnOI with a dynamical ensemble to generate 30 members to represent the analysis uncertainty, in which the instrumental uncertainty and reconstruction (sampling/mapping) uncertainty are represented by the spread over the 30 members30,108. As more global and long-term scale observational temperature products are available, other independent products, such as the Ishii temperature gridded product36 at 1° x 1° for the upper 3,000 m from 1960 to 2022 (version 7.3.1), are used to check the robustness of the temperature ToE. The technical processing is similar to the IAP temperature dataset, with the main differences in gapping filling (interpolation to the climatology), XBT bias correction and data quality control schemes36,103.

For salinity, we also use the latest versions of IAP monthly salinity global ocean gridded products with the same temporal–spatial resolution as the temperature dataset30. The strength of the IAP salinity product shares similarities with the IAP temperature product, with an updated quality control method109, using the most up-to-date delayed-mode Argo in situ profiles110, an EnOI method108 and an analysis of uncertainty that accounts for instrumental uncertainty and sampling/mapping uncertainty that are represented by the spread over the 36 salinity members30,108. Similarly, with temperature products, the Ishii salinity gridded product36 at 1° x 1° for the upper 3,000 m from 1960 to 2022 (version 7.3.1) is also used to check the robustness of the result of salinity emergence.

For dissolved oxygen, the IAP monthly oxygen global ocean gridded products at 1° × 1° horizontal resolution for the upper 6,000 m with 119 standard vertical levels from 1960 to 2022 are used111,112. This dataset also combines three available instruments (CTD, Bottle and Argo) with a bias adjustment for delay-mode Argo oxygen profiles to ensure the data consistency between different oxygen instruments112, a new quality control method to detect the outliers112, and the EnOI method to fill the data-gap regions and give objective analyses of uncertainty that account for instrumental uncertainty and sampling/mapping uncertainty that are represented by the spread over the 30 dissolved oxygen members108. This IAP product is a monthly product but combines 3 years of data for its monthly estimate because of the data sparseness37. As more global-scale observational products for ocean oxygen are available, we also utilized another independent monthly observational gridded product to evaluate the robustness of the main findings: Global Upper Ocean Dissolved Oxygen Anomaly Dataset (version 2; referred to as the ‘Ito’ dataset37).

The pH data (pH on total scale) are from the Global Ocean Surface Carbon dataset, at 0.25° × 0.25° horizontal resolution from 1985 to 2021, managed by the Copernicus Marine Service113. This monthly satellite observational-based product uses a multivariate linear regression (Locally Interpolated Alkalinity Regression) and the CO2sys speciation software error propagation to estimate the reconstruction uncertainty, which is represented as a standard deviation of pH. This product has been evaluated by independent data, including surface ocean carbon dioxide partial pressure and surface ocean alkalinity114. In addition, the OceanSODA-ETHZ satellite pH data product115 at a 1° box from 1985 to 2021 is utilized to test the robustness of the result of surface pH emergence. Here we investigate only the emergence of surface acidification because up-to-date, observational- (reanalysis) based data products available now114,116,117,118,119 do not have long time series with global coverage to perform the subsurface acidification ToE estimates.

The term ‘CID’ is used as an approach to guiding the oceanic physical change to the impact of climate change (for example, compound effects on marine biology; Box 1). Therefore, in this study, based on the penetration of sunlight and the distribution of marine life120, we consider the ToE at depth in the following three layers: (1) surface (0 m); (2) epipelagic zone (euphotic zone; 0–200 m) and (3) mesopelagic zone (twilight zone; 200–1,000 m).

ToE and its uncertainty estimation

In this study, the ToE of each CID is estimated following the definitions in ref. 10, which refers to the time when the long-term signal emerges from the background noise and never falls back again into the noise threshold during the entire analysis period10. A linear regression from the global change to the local change is used in each 1° box at each depth:

where \(L\left(t\right)\) is the local anomaly time series for each CID in each grid cell, \(G\left(t\right)\) is the corresponding smoothed version of global average with 25-year LOWESS filter smoothing. For salinity, \(G\left(t\right)\) is the salinity contrast time series following the method introduced by Cheng et al.30 for the same period. Testing the sensitivity of this choice with CMIP6 model data revealed no significant difference between applying a 25-year and a 50-year filter (Supplementary Figs. 1–3). The \(\alpha\) is the linear scaling factor between \(L\left(t\right)\) and \(G\left(t\right)\), and \(\beta\) is the residual term. Here the local signal (S) changing with time is \(\alpha \times G\left(t\right)\), representing the local signal of long-term climate signal (Supplementary Fig. 8). The local noise (N) is defined as the standard deviation of the residuals (\(L-\alpha \times G\left(t\right)\)), which is constant with time (Supplementary Fig. 9). Then the SNR is calculated (SNR measures how far the climate is being shifted from this past range; Supplementary Fig. 10). The ToE is then defined as the first year in which |SNR| > 1 (ref. 121; see examples in Supplementary Fig. 11). |SNR| > 1 denotes the ToE is estimated on the 67% confidence level of the estimated short-term variability defined by noise. But the ToE results using |SNR| > 2 (that is, 95% confidence level of the emergence) are also presented (Figs. 2 and 3; further details in Methods, ‘Sensitivity of SNR choice’). Previous studies have performed sensitivity tests on the SNR calculation, showing that different choices of SNR threshold do not substantially impact the main conclusions or the overall narrative121,122. Reference 9 indicates that the local SNR may fall back again into the noise level because of the impact from the (multi-)decadal variability. Note that this case will not likely occur for temperature and salinity in this study within the investigated period because the local emergence is defined by the scaled monotonically increased global signals with a 25-year signal versus noise cut-off. Nevertheless, an additional CMIP6 sensitivity test by changing the cut-off period of 25 years to 50 years demonstrates that the impact of this case is relatively small (we have included this uncertainty as ‘uncertainty due to the quantification of signal’ into the total uncertainty; Extended Data Fig. 8 and Supplementary Figs. 1–3).

Since most of the data are available for about the past ~60 years, we used a 25-year cut-off threshold to separate long-term signal change and noise (for example, due to data noise and internal variability), following ref. 22. The chlorophyll-a and net primary production (which are also classified as the ocean CIDs because these variables can strongly affect ocean ecosystems such as biomass, species habitats and food webs74) cannot currently be included in our study due to the length of available observational data (available for only about 25 years123; see Supplementary Information section C for an assessment). In addition, as our research focuses on long-term ocean state changes, CIDs that represent short-term timescale variability, such as annual, interannual or decadal variability, or extreme events (for example, marine heatwaves) are not addressed here. The polar regions (beyond 70° N and 60° S) are not examined due to lack of data.

The uncertainty in estimating the ToE depends primarily on the following sources of errors: data sampling and mapping approach, instrumental systematic biases108, the existence of (multi-)decadal variability that impacts the quantification of the climate change signal and reference period (baseline) choice and so on. Four major sources of uncertainties are accounted for in the overall ToE uncertainty estimation: instrumental uncertainty, mapping uncertainty, sampling uncertainty and uncertainty due to decadal variability in the quantification of the signal and baseline choice (Extended Data Fig. 8), described as follows.

For temperature, salinity and dissolved oxygen, the mapping uncertainty, sampling uncertainty and instrumental uncertainty are estimated using ensemble members provided by IAP products108 (30 members for temperature, 36 members for salinity and 30 members for dissolved oxygen). The warming/cooling (or salinization/freshening; or deoxygenation/oxygenation) emergence at the 95% uncertainty range, represented by the ensemble members of the data products, is calculated following the approach of refs. 9,122. Taking temperature as an example, the ToE is first estimated for each of the 30 members following the definition of ref. 10 (equation (1)), which are then divided into three groups: (A) warming emergence, (B) cooling emergence and (C) no emergence. The final estimate of ToE and its 95% data uncertainty range (the 2.5th percentile to the 97.5th percentile) is defined following the decision tree provided in Extended Data Fig. 9. A long-term change is defined as ‘significant emergence’ only if both the ToE and its 95% uncertainty range are earlier than 2023. Otherwise, it is defined as an ‘insignificant emergence’.

For surface pH, the Copernicus Marine Global Ocean Surface Carbon surface pH data (Copernicus Marine Service) provides the uncertainty estimate with a standard deviation error estimate, taking into account the reconstruction error and the errors of various predictors113,124. Here we define the 95% uncertainty range due to the data product uncertainty as two times the standard deviation interval.

For temperature, salinity and dissolved oxygen, we use the following method to estimate the ToE uncertainty range due to decadal variability in the quantification of the signal and baseline choice (because the long-term climatic changes signals are defined as changes at timescales longer than 15–20 years and the baseline is defined as 30 years from 1960 to 1989 in this study). Some climate (multi-)decadal variability exhibiting periodicities of up to 50 years can potentially impact our ToE calculation (long-term change estimation) through two methodology choices: (1) the baseline setting and (2) the 25-year signal cut-off period of smoothing for G(t). A sensitivity test is performed by using CMIP6 historical and Shared Socioeconomic Pathways (SSP2 4.5) simulation data125. We (1) increase the LOWESS smoothing windows from 25 to 50 years to quantify the signal and (2) increase the baseline choice from 20 years (1960–1979) to 50 years (1935–1984; although our main text uses a 30‑year baseline, testing the sensitivity over an ~20–50 year range here establishes an upper bound on the uncertainty estimate; also see Supplementary Fig. 12). We then investigate the ToE from 1960 to 2023. The difference between ‘25 years smooth version and 20 years baseline’ and ‘50 years smoothing version and 50 years baseline’ can be used to assess the impact of decadal variability; this is because the 50 years LOWESS smoothing and 50 years baseline could effectively smooth most of the natural decadal variability (that is, the Pacific Decadal Oscillation has a period of 10–30 years (ref. 126) and the Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation has a period of 50–80 years (ref. 127)). Here multimodel ensemble strategies are considered because different models can simulate different decadal variability56: 23 models for temperature, 16 for salinity and 10 for dissolved oxygen (Supplementary Table 1). The ‘climate drift’ (due to the model errors) in each model is subtracted using a ‘quadratic’ polynomial regression in each grid box following the suggestions of Cheng et al.30. In both cases, the same ToE method was applied, with the only difference being the signal definition and baseline choice. Following refs. 9,122, the 95% emergence uncertainty range is represented by the spread of the model (that is, multimodel ensemble median and 2.5–97.5% range)

The results show that (1) for temperature, regionally, the ToE difference in 2022 between Group A and Group B can be up to 2–4 (±3) years (with a 95% confidence level), with a global percentage area difference of 0–4% (Supplementary Fig. 1); (2) for salinity, the impact of the decadal variability can be up to 5 (±4) years and ~0–4% difference for the global percentage area (Supplementary Fig. 2); (3) for dissolved oxygen, the impact can be up to 6 (±4) years and ~0–2% (Supplementary Fig. 3). Spatially, the substantial impact is distributed mainly around the ‘key regions’ of Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation and Pacific Decadal Oscillation variability (for example, North Atlantic Subtropical Gyre, North Central Pacific and the Southern Ocean). For the worst cases, the impacts can be up to 6 (±4) years and 4% for the global percentage emergence for temperature, salinity and dissolved oxygen. We conclude that, although the decadal variability can introduce a small error to the ToE estimates, varying the LOWESS smoothing windows from 25 up to 50 years and changing the baseline from 20 years to 50 years will not substantially change the estimates of the ToE, and 25-year smoothing version and 30 years baseline (1960–1989) is a reasonable choice to detect the observed long-term change since 1960 in this study (given the relatively short observational record). Nevertheless, this uncertainty (referred to in this study as ‘uncertainty due to decadal variability in the quantification of signal and the baseline choice’) is added to the sampling/mapping/instrumental uncertainty previously defined to derive the total uncertainty of compound emergence (Extended Data Fig. 8). By simply summing the two errors, we do not assume that the two sources are independent, resulting in an upper bound on the uncertainty estimate.

Extended Data Figs. 1–4 show the results of individual ToE (for temperature, salinity, dissolved oxygen and surface pH, respectively) from 1960 to 2023. We observe that a large fraction of the global ocean has already shifted to a new climate state compared with 40–60 years ago, despite the climate background variability and observational errors. Although we are focusing on the entire upper 1,000 m of ocean changes, sea surface changes are compared with previous investigations, showing that the spatial and temporal ToE patterns of surface temperature, surface salinity and surface pH are consistent with the previous publications10,11,14,30,121,128.

Robustness of the results on the choice of observational data products

IAP data products are used as a central estimate of ToE of temperature/salinity/dissolved oxygen mainly because (1) they provide consistent uncertainty estimates for all variables, so the results are consistent for all key variables investigated in this study30,103,108; (2) previous independent evaluations129,130 indicate the IAP products are particularly robust for long-term change studies despite the data quality and data sparsity issues. Here it is mandatory to test the robustness of the results for independent products. For temperature and salinity, the Ishii temperature/salinity gridded product36 is used, in which the data-gap filling, bias correction and quality control schemes are different from the IAP products. For dissolved oxygen, the Ito Dataset37 is used, in which the main differences of this product with IAP product is in mapping strategies, data sources, data quality control, bias correction, and small-scale and high-frequency variability analysing. For pH, the OceanSODA-ETHZ satellite pH data product115 is also used to check the robustness. The results of ToE for temperature, salinity, dissolved oxygen and surface pH are robust among different observational products used (Extended Data Figs. 1 and 5–7). More specifically, the medium- to high-exposure regions (that is, the North Atlantic Ocean, the tropical Atlantic Ocean, the Mediterranean Sea and the Arabian Sea; Fig. 3) can be generally identified by using the Ishii dataset for temperature and salinity, the Ito dataset for dissolved oxygen and the OceanSODA-ETHZ dataset for surface pH.

The compound CID emergence and its uncertainty estimation

The methods for determining the compound CID emergence (that is, double emergence and triple emergence) have briefly been discussed in the main text (Box 1). The overall ToE uncertainty of compound CIDs is estimated using a Monte Carlo approach131 (shown in Extended Data Fig. 8). In detail, in each Monte Carlo simulation, we randomly select one member from each individual CID, and then we define the double and triple emergence regions for each simulation following the approach shown in Box 1. This process is repeated 3,500 times for double CIDs and 80,000 times for triple CIDs to generate a set of realizations with different emergence directions (for example, only warming emergence, only salinization emergence, both warming and salinization emergence, no emergence). These Monte Carlo simulations of different variables are combined to provide an ensemble for double emergence and triple emergence separately. To determine the confidence interval on the basis of these ensembles, we follow the approach of ref. 122, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 13, with the Monte Carlo realizations. Then the ‘significant double emergence’ and ‘significant triple emergence’ regions (for example, significant warming and salinization) are represented by the median year with ToE and the 95% uncertainty range across all realizations.

Definitions and calculations of duration, intensity and magnitude of emergence and the resulting exposure

The intensity of emergence for individual CIDs is defined as how strongly the signal has been changed since it emerged from the background noise, quantified by the SNR in 2023 (that is, represented by the intercept in panel a of the figure in Box 1). Duration of emergence for individual CIDs is defined as how long the signal has been changed since it emerged from the noise (that is, the persistence of emergence), quantified by the difference between 2023 and its time of emergence (that is, 2023–ToE). The unit is the year. The magnitude of emergence for individual CIDs is defined as how fast the signal has been changed since it emerged from the noise, quantified by its linear trend (linear regression; represented by the slope in panel a of the figure in Box 1). The units are °C decade−1 for temperature, PSU decade−1 for salinity, μmol kg−1 decade−1 for dissolved oxygen and pH units decade−1 for surface pH. Here the magnitude refers to the rate of signal change and can be jointly determined by the duration and intensity of emergence. Therefore, magnitude is a function of duration and intensity (see panel a of the figure in Box 1; these three terms correspond to the three sides of the triangle, which can be explained by the Pythagorean Theorem).

These three metrics are quantified in each 1° box at each standard depth level on the basis of a data distribution approach (see panel b of the figure in Box 1). In detail, following previous studies of individual CIDs132,133, we first normalized all these metrics to values between 0 and 1. Second, the values of each metric are divided into three groups—high (long), medium and low (short)—based on its probability density distribution. The threshold between high and medium is set to the median plus one median absolute deviation. The threshold between medium and low (short) is set to zero (equal to zero denotes ‘no emergence’), indicating the regions of no emergence. Specifically, for surface pH, the threshold between high and medium is set as the fifth percentile. For the definitions of duration, intensity and magnitude of compound CID emergence, the high (long), medium and low (short) categories are defined on the basis of the individual CIDs (Supplementary Table 2). The results are shown in Supplementary Fig. 4 and discussed in section D of the Supplementary Information. Finally, ocean exposure (three categories: high, medium, low) to the long-term compound CIDs is then defined on the basis of the three metrics: duration of emergence, intensity of emergence and magnitude of emergence. Here ‘high exposure’ refers to a situation where at least two of the above three metrics are ‘high’, and ‘low exposure’ refers to a situation where at least two of the three metrics are ‘low’, while the ‘medium exposure’ refers to the remaining situations (see panel c of figure in Box 1 and Supplementary Table 2). It is important to note that our focus is not on exposure attribution, exposure for risk assessment, studies of exposed specific marine species or populations, or studies of marine ecosystem impacts from the emergence of compound CIDs (that is, compound effects). Instead, we use a general approach to investigate and understand how the global ocean is exposed to long-term compound CIDs, establishing a connection between the oceanic physical science basis and their climate change impacts.

Sensitivity of SNR choice

In this study, two types of uncertainties/confidences are presented: (1) the uncertainty range arising from ensemble members of the data products (Extended Data Fig. 9 and Supplementary Fig. 13) and (2) the confidence level associated with the SNR threshold in the ToE definition. The robustness of the confidence level due to varying SNR thresholds corresponds to the confidence level of the estimated short-term variability (|SNR| > 1 ≈ 67% confidence, |SNR| > 2 ≈ 95% confidence122). Here we examined how varying the SNR threshold affects the identification of emergence. Increasing the |SNR| threshold to 2 reduces the area of emergence before 2023 (red dots in Fig. 2). However, this change does not alter the spatial patterns or the identification of key compound climate change hotspots (that is, high exposure regions; Fig. 3). Therefore, adjusting the SNR threshold does not impact the overall narrative as the higher threshold is simply more conservative122. Both |SNR| > 1 and |SNR| > 2 thresholds are used in the literature9,10,121,122,134, each with its own caveats: |SNR| > 1 corresponds to a 67% confidence level of the estimated short-term variability defined by noise, which may include some regions affected by short-term variability; |SNR| > 2 corresponds to a 95% confidence level of that emergence but may be too conservative, potentially missing early changes given the limited observational record (starting ~1960). Presenting both levels of confidence ensures transparency and allows us to capture a wider distribution of possible emergences (Figs. 2 and 3). In addition, we note that most of the ‘high-exposure’ regions identified in this study (dark brown, green and purple in Fig. 3) have |SNR| > 2, indicating that this more-stringent threshold is already incorporated into our exposure definitions. Specifically, high exposure is determined by the intensity, duration and magnitude of emergence (see panel c of the figure in Box 1), where high intensity typically corresponds to |SNR| values greater than 2.

Data availability

The data used to capture and monitor compound ocean state changes using ToE and exposure metrics (Figs. 2 and 3; we named it the “IAP compound CIDs dataset”) in this study is available at http://www.ocean.iap.ac.cn/ftp/cheng/Compound_CIDs/ (with providing some visualizing codes for policymakers or climate services). The IAP (Institute of Atmospheric Physics) temperature gridded product (version 4) is available at https://doi.org/10.12157/IOCAS.20240117.002 and http://www.ocean.iap.ac.cn/ftp/cheng/IAPv4.2_IAP_Temperature_gridded_1month_netcdf/. The IAP salinity gridded product is available at http://www.ocean.iap.ac.cn/ftp/cheng/CZ16_v0_IAP_Salinity_gridded_1month_netcdf/. The IAP dissolved oxygen gridded product is available at http://www.ocean.iap.ac.cn/ftp/cheng/IAP_v0_Ocean_Oxygen_gridded_1deg_0_6000m_dataset/ and http://www.ocean.iap.ac.cn/ftp/cheng/IAP_oxygen_profile_dataset/. The Global Upper Ocean Dissolved Oxygen Anomaly Dataset (version 2) is available at https://www.bco-dmo.org/dataset/816978. The Copernicus Marine Service—Global Ocean Surface Carbon product is available at https://doi.org/10.48670/moi-00047. The OceanSODA-ETHZ product is available at https://doi.org/10.25921/m5wx-ja34. The Ishii temperature and salinity products are available at https://climate.mri-jma.go.jp/pub/ocean/ts/v7.3.1.

Code availability

The codes to reproduce the main text figures can be accessed via the Code Ocean135: https://doi.org/10.24433/CO.6650239.v1 or http://www.ocean.iap.ac.cn/ftp/cheng/Compound_CIDs/.

References

IPCC Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis (eds Masson-Delmotte, V. et al.) (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2021).

IPCC Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability (eds Pörtner, H.-O. et al.) (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2022).

Bopp, L. et al. Multiple stressors of ocean ecosystems in the 21st century: projections with CMIP5 models. Biogeosciences 10, 6225–6245 (2013).

Ranasinghe, R. et al. in Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis (eds Masson-Delmotte, V. et al.) Ch. 12 (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2021).

IPCC: Summary for Policymakers. In IPCC Special Report on the Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate (eds Pörtner, H.-O. et al.) (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2019).

Cooley, S. et al. in Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability (eds Pörtner, H.-O. et al.) Ch. 3 (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2022).

von Schuckmann, K., Holland, E., Haugan, P. & Thomson, P. Ocean science, data, and services for the UN 2030 Sustainable Development Goals. Mar. Policy 121, 104154 (2020).

Zhang, X. B. & Church, J. A. Sea level trends, interannual and decadal variability in the Pacific Ocean. Geophys. Res. Lett. 39, L21701 (2012).

Lyu, K., Zhang, X., Church, J. A., Slangen, A. B. A. & Hu, J. Time of emergence for regional sea-level change. Nat. Clim. Change 4, 1006–1010 (2014).

Hawkins, E. et al. Observed emergence of the climate change signal: from the familiar to the unknown. Geophys. Res. Lett. 47, e2019GL086259 (2020).

Schlunegger, S. et al. Time of emergence and large ensemble intercomparison for ocean biogeochemical trends. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 34, e2019GB006453 (2020).

Nguyen, T.-H., Min, S.-K., Paik, S. & Lee, D. Time of emergence in regional precipitation changes: an updated assessment using the CMIP5 multi-model ensemble. Clim. Dyn. 51, 3179–3193 (2018).

Gruber, N., Boyd, P. W., Frölicher, T. L. & Vogt, M. Biogeochemical extremes and compound events in the ocean. Nature 600, 395–407 (2021).

Wong, J., Munnich, M. & Gruber, N. Column-compound extremes in the global ocean. AGU Adv. 5, e2023AV001059 (2024).

Schlunegger, S. et al. Emergence of anthropogenic signals in the ocean carbon cycle. Nat. Clim. Change 9, 719–725 (2019).

Gruber, N. Warming up, turning sour, losing breath: ocean biogeochemistry under global change. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. A 369, 1980–1996 (2011).

Multiple Ocean Stressors: A Scientific Summary for Policy Makers (IOC Information Series, 2022).

Schleussner, C.-F. et al. 1.5 °C hotspots: climate hazards, vulnerabilities, and impacts. Annu Rev. Environ. Resour. 43, 135–163 (2018).

Grant, L. et al. Global emergence of unprecedented lifetime exposure to climate extremes. Nature 641, 374–379 (2025).

Le Grix, N., Cheung, W. L., Reygondeau, G., Zscheischler, J. & Frölicher, T. L. Extreme and compound ocean events are key drivers of projected low pelagic fish biomass. Glob. Change Biol. 29, 6478–6492 (2023).

Seneviratne, S. I. et al. in Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis (eds Masson-Delmotte, V. et al.) 1513–1766 (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2021).

Cheng, L., Foster, G., Hausfather, Z., Trenberth, K. E. & Abraham, J. Improved quantification of the rate of ocean warming. J. Clim. 35, 4827–4840 (2022).

Giorgi, F. & Bi, X. Time of emergence of GHG-forced precipitation change hot-spots. Geophys. Res. Lett. 36, L06709 (2009).

Mahlstein, I., Hegerl, G. & Solomon, S. Emerging local warming signals in observational data. Geophys. Res. Lett. 39, L21711 (2012).

Hameau, A., Mignot, J. & Joos, F. Assessment of time of emergence of anthropogenic deoxygenation and warming: insights from a CESM simulation from 850 to 2100. Biogeosciences 16, 1755–1780 (2019).

Le Cozannet, G. et al. Timescales of emergence of chronic flooding in the major economic center of Guadeloupe. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 21, 703–722 (2021).

Cheng, L. et al. Past and future ocean warming. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 3, 776–794 (2022).

Cheng, L. et al. How fast are the oceans warming. Science 363, 128–129 (2019).

Minière, A., von Schuckmann, K., Sallée, J.-B. & Vogt, L. Robust acceleration of Earth system heating observed over the past six decades. Sci. Rep. 13, 22975 (2023).

Cheng, L. et al. Improved estimates of changes in upper ocean salinity and the hydrological cycle. J. Clim. 2020, 10357–10381 (2020).

Durack, P. J. & Wijffels, S. E. Fifty-year trends in global ocean salinities and their relationship to broad-scale warming. J. Clim. 23, 4342–4362 (2010).

Trenberth, K. E. Changes in precipitation with climate change. Clim. Res 47, 123–138 (2011).

Lu, Y. et al. North Atlantic–Pacific salinity contrast enhanced by wind and ocean warming. Nat. Clim. Change 14, 723–731 (2024).

Zanna, L., Khatiwala, S., Gregory, J. M., Ison, J. & Heimbach, P. Global reconstruction of historical ocean heat storage and transport. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 116, 1126–1131 (2019).

Ito, T., Minobe, S., Long, M. C. & Deutsch, C. Upper ocean O2 trends: 1958–2015. Geophys. Res. Lett. 44, 4214–4223 (2017).

Ishii, M. et al. Accuracy of global upper ocean heat content estimation expected from present observational data sets. Sola 13, 163–167 (2017).

Ito, T. Optimal interpolation of global dissolved oxygen: 1965–2015. Geosci. Data J. 9, 167–176 (2022).

Li, G. et al. A global gridded ocean salinity dataset with 0.5° horizontal resolution since 1960 for the upper 2000 m. Front. Mar. Sci. 10, 1108919 (2023).

Good, S. A., Martin, M. J. & Rayner, N. A. EN4: quality controlled ocean temperature and salinity profiles and monthly objective analyses with uncertainty estimates. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 118, 6704–6716 (2013).

Li, G. et al. Increasing ocean stratification over the past half-century. Nat. Clim. Change 10, 1116–1123 (2020).

Schmidtko, S., Stramma, L. & Visbeck, M. Decline in global oceanic oxygen content during the past five decades. Nature 542, 335–339 (2017).

Wooster, W. S., Bakun, A. & McLain, D. R. The seasonal upwelling cycle along the eastern boundary of the North Atlantic. J. Mar. Res. 34, e2022JC019487 (1976).

Garçon, V. et al. Multidisciplinary observing in the world ocean’s oxygen minimum zone regions: from climate to fish—the VOICE Initiative. Front. Mar. Sci. 6, 722 (2019).

Buckley, M. W. & Marshall, J. Observations, inferences, and mechanisms of the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation: a review. Rev. Geophys. 54, 5–63 (2016).

Pinardi, N., Cessi, P., Borile, F. & Wolfe, C. L. The Mediterranean Sea overturning circulation. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 49, 1699–1721 (2019).

Stramma, L. & Siedler, G. Seasonal changes in the North Atlantic subtropical gyre. J. Geophys Res. Oceans 93, 8111–8118 (1988).

Zhu, C. & Liu, Z. Weakening Atlantic overturning circulation causes South Atlantic salinity pile-up. Nat. Clim. Change 10, 998–1003 (2020).

Schmitz, W. J. Jr & McCartney, M. S. On the North Atlantic circulation. Rev. Geophys. 31, 29–49 (1993).

Kumar, S. P., Roshin, R. P., Narvekar, J., Kumar, P. D. & Vivekanandan, E. Response of the Arabian Sea to global warming and associated regional climate shift. Mar. Environ. Res. 68, 217–222 (2009).

Piontkovski, S. & Chiffings, T. Long-term changes of temperature in the Sea of Oman and the western Arabian Sea. Int. J. Oceans Oceanogr. 8, 53–72 (2014).

Lachkar, Z., Lévy, M. & Smith, K. S. Strong intensification of the Arabian Sea oxygen minimum zone in response to Arabian Gulf warming. Geophys. Res. Lett. 46, 5420–5429 (2019).

Menezes, V. V. Advective pathways and transit times of the Red Sea Overflow Water in the Arabian Sea from Lagrangian simulations. Prog. Oceanogr. 199, 102697 (2021).

Albert, J., Gulakaram, V. S., Vissa, N. K., Bhaskaran, P. K. & Dash, M. K. Recent warming trends in the Arabian Sea: causative factors and physical mechanisms. Climate 11, 35 (2023).

Vinayachandran, P. et al. A summer monsoon pump to keep the Bay of Bengal salty. Geophys. Res. Lett. 40, 1777–1782 (2013).

Jensen, T. G. et al. Modeling salinity exchanges between the equatorial Indian Ocean and the Bay of Bengal. Oceanography 29, 92–101 (2016).

Kwiatkowski, L. et al. Twenty-first century ocean warming, acidification, deoxygenation, and upper-ocean nutrient and primary production decline from CMIP6 model projections. Biogeosciences 17, 3439–3470 (2020).

Sallée, J.-B. et al. Summertime increases in upper-ocean stratification and mixed-layer depth. Nature 591, 592–598 (2021).

Altieri, A. H. & Gedan, K. B. Climate change and dead zones. Glob. Change Biol. 21, 1395–1406 (2015).

Nowicki, M., DeVries, T. & Siegel, D. A. Quantifying the carbon export and sequestration pathways of the ocean’s biological carbon pump. Glob. Biogeochem. Cy 36, e2021GB007083 (2022).

Kroodsma, D. A. et al. Tracking the global footprint of fisheries. Science 359, 904–908 (2018).

Stewart-Sinclair, P. J., Last, K. S., Payne, B. L. & Wilding, T. A. A global assessment of the vulnerability of shellfish aquaculture to climate change and ocean acidification. Ecol. Evol. 10, 3518–3534 (2020).

Cavan, E. L., Henson, S. A. & Boyd, P. W. The sensitivity of subsurface microbes to ocean warming accentuates future declines in particulate carbon export. Front. Ecol. Evol. 6, 230 (2019).

Hodapp, D. et al. Climate change disrupts core habitats of marine species. Glob. Change Biol. 29, 3304–3317 (2023).

Agreement Under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea on the Conservation and Sustainable Use of Marine Biological Diversity of Areas Beyond National Jurisdiction (United Nations, 2023).

Cheng, L. Sensitivity of ocean heat content to various instrumental platforms in global ocean observing system. Ocean Land Atmos Res. 3, p0037 (2023).

GCOS. The Status of the Global Climate Observing System 2021: The GCOS Status Report (GCOS-240) Pub. WMO (GCOS, 2021).

Moltmann, T., et al. A global ocean observing system (GOOS), delivered through enhanced collaboration across regions, communities, and new technologies. Front. Mar. Sci. 6, 291 (2019).

Müller, J. D. & Gruber, N. Progression of ocean interior acidification over the industrial era. Sci. Adv. 10, eado3103 (2024).

Griffith, G. P., Fulton, E. A., Gorton, R. & Richardson, A. J. Predicting interactions among fishing, ocean warming, and ocean acidification in a marine system with whole-ecosystem models. Conserv Biol. 26, 1145–1152 (2012).

Baco, A. R., et al. Defying dissolution: discovery of deep-sea scleractinian coral reefs in the North Pacific. Sci. Rep. 7, 5436 (2017).

Yu, K. Coral reefs in the South China Sea: their response to and records on past environmental changes. Sci. China Earth Sci. 55, 1217–1229 (2012).

Ban, Z., Hu, X. & Li, J. Tipping points of marine phytoplankton to multiple environmental stressors. Nat. Clim. Change 12, 1045–1051 (2022).

Lopes, P. F., Pennino, M. G. & Freire, F. Climate change can reduce shrimp catches in equatorial Brazil. Reg. Environ. Change 18, 223–234 (2018).

Brown, C. et al. Effects of climate-driven primary production change on marine food webs: implications for fisheries and conservation. Glob. Change Biol. 16, 1194–1212 (2010).

Van der Stocken, T., Vanschoenwinkel, B., Carroll, D., Cavanaugh, K. C. & Koedam, N. Mangrove dispersal disrupted by projected changes in global seawater density. Nat. Clim. Change 12, 685–691 (2022).

Shields, J. D. Climate change enhances disease processes in crustaceans: case studies in lobsters, crabs, and shrimps. J. Crustac. Biol. 39, 673–683 (2019).

Albouy, C. et al. Global vulnerability of marine mammals to global warming. Sci. Rep. 10, 548 (2020).

Talukder, B., Ganguli, N., Matthew, R., Hipel, K. W. & Orbinski, J. Climate change-accelerated ocean biodiversity loss & associated planetary health impacts. J. Clim. Change Health 6, 100114 (2022).

Link, J. S. What does ecosystem-based fisheries management mean. Fisheries 27, 18–21 (2002).

Lee, K.-H., Noh, J. & Khim, J. S. The blue economy and the United Nations’ sustainable development goals: challenges and opportunities. Environ. Int. 137, 105528 (2020).

Ara Begum, R. et al. in Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability (eds Pörtner, H.-O. et al.) Ch. 1 (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2022).

Pierce, D. W., Gleckler, P. J., Barnett, T. P., Santer, B. D. & Durack, P. J. The fingerprint of human-induced changes in the ocean’s salinity and temperature fields. Geophys. Res. Lett. 39, L21704 (2012).

Levin, L. A. Manifestation, drivers, and emergence of open ocean deoxygenation. Annu. Rev. Mar. Sci. 10, 229–260 (2018).

Frederikse, T. et al. The causes of sea-level rise since 1900. Nature 584, 393–397 (2020).

Simpson, N. P. et al. A framework for complex climate change risk assessment. One Earth 4, 489–501 (2021).

Vaquer-Sunyer, R. & Duarte, C. M. Temperature effects on oxygen thresholds for hypoxia in marine benthic organisms. Glob. Change Biol. 17, 1788–1797 (2011).

Rodriguez-Dominguez, A., Connell, S. D., Baziret, C. & Nagelkerken, I. Irreversible behavioural impairment of fish starts early: embryonic exposure to ocean acidification. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 133, 562–567 (2018).

Venegas, R. M., Acevedo, J. & Treml, E. A. Three decades of ocean warming impacts on marine ecosystems: a review and perspective. Deep Sea Res 2 212, 105318 (2023).

IPCC: Annex VII: Glossary. In Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis (eds Matthews, J. B. R. et al.) 541–562 (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2022).

Sarhadi, A., Ausín, M. C., Wiper, M. P., Touma, D. & Diffenbaugh, N. S. Multidimensional risk in a nonstationary climate: joint probability of increasingly severe warm and dry conditions. Sci. Adv. 4, eaau3487 (2018).

Bezner Kerr, R. et al. in Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability (eds Pörtner, H.-O. et al.) 713–906 (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2022).

Pflaumann, U., Duprat, J., Pujol, C. & Labeyrie, L. D. SIMMAX: a modern analog technique to deduce Atlantic sea surface temperatures from planktonic foraminifera in deep-sea sediments. Paleoceanography 11, 15–35 (1996).

Holbrook, N. J. et al. A global assessment of marine heatwaves and their drivers. Nat. Commun. 10, 2624 (2019).

Lowe, R. et al. Combined effects of hydrometeorological hazards and urbanisation on Dengue risk in Brazil: a spatiotemporal modelling study. Lancet Planet. Health 5, e209–e219 (2021).

Gianguzza, P. et al. Temperature modulates the response of the thermophilous sea urchin Arbacia lixula early life stages to CO2-driven acidification. Mar. Environ. Res 93, 70–77 (2014).

Guinotte, J. M. & Fabry, V. J. Ocean acidification and its potential effects on marine ecosystems. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1134, 320–342 (2008).

Keeling, R. F., Körtzinger, A. & Gruber, N. Ocean deoxygenation in a warming world. Annu. Rev. Mar. Sci. 2, 199–229 (2010).

Piontek, J., Sperling, M., Nöthig, E. M. & Engel, A. Multiple environmental changes induce interactive effects on bacterial degradation activity in the Arctic Ocean. Limnol. Oceanogr. 60, 1392–1410 (2015).

Bindoff, N. L. et al. in IPCC Special Report on the Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate (eds Pörtner, H.-O. et al.) Ch. 5 (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2019).

Trisos, C. H., Merow, C. & Pigot, A. L. The projected timing of abrupt ecological disruption from climate change. Nature 580, 496–501 (2020).

Brito-Morales, I. et al. Climate velocity reveals increasing exposure of deep-ocean biodiversity to future warming. Nat. Clim. Change 10, 576–581 (2020).

Ruane, A. C., et al. The climatic impact-driver framework for assessment of risk-relevant climate information. Earths Future 10, e2022EF002803 (2022).

Cheng, L. et al. IAPv4 ocean temperature and ocean heat content gridded dataset. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2024, 3517–3546 (2024).

Cheng, L. et al. How well can we correct systematic errors in historical XBT data? J. Atmos. Ocean Technol. 35, 1103–1125 (2018).

Gouretski, V. & Cheng, L. Correction for systematic errors in the global data set of temperature profiles from mechanical bathythermographs. J. Atmos. Ocean Technol. 37, 841–855 (2020).

Tan, Z. et al. Examining the influence of recording system on the pure temperature error in XBT data. J. Atmos. Ocean Technol. 38, 759–776 (2021).

Tan, Z., et al. A new automatic quality control system for ocean profile observations and impact on ocean warming estimate. Deep Sea Res. 1 194, 103961 (2023).

Cheng, L. & Zhu, J. Benefits of CMIP5 multimodel ensemble in reconstructing historical ocean subsurface temperature variations. J. Clim. 29, 5393–5416 (2016).

Tan, Z. et al. CODC-S: A quality-controlled global ocean salinity profiles dataset. Sci. Data 12, 917 (2025).

Cheng, L. et al. New record ocean temperatures and related climate indicators in 2023. Adv. Atmos. Sci. 41, 1068–1082 (2024).

Cheng, L. & Gouretski, V. IAP Global Ocean Oxygen Gridded Product (1-degree) (Chinese Academy of Sciences, 2023); https://doi.org/10.12157/IOCAS.20231214.006

Gouretski, V. et al. A consistent ocean oxygen profile dataset with new quality control and bias assessment. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 16, 5503–5530 (2024).

Chau, T. T. T., Gehlen, M. & Chevallier, F. A seamless ensemble-based reconstruction of surface ocean \({p}_{{\mathrm{CO}}_{2}}\) and air–sea CO2 fluxes over the global coastal and open oceans. Biogeosciences 19, 1087–1109 (2022).

Fassbender, A. J., et al. Amplified subsurface signals of ocean acidification. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 37, e2023GB007843 (2023).

Gregor, L. & Gruber, N. OceanSODA-ETHZ: a global gridded data set of the surface ocean carbonate system for seasonal to decadal studies of ocean acidification. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 13, 777–808 (2021).

Lauvset, S. K. et al. A new global interior ocean mapped climatology: the 1 × 1 GLODAP version 2. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 8, 325–340 (2016).

Broullón, D. et al. A global monthly climatology of total alkalinity: a neural network approach. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 11, 1109–1127 (2019).

Broullón, D. et al. A global monthly climatology of oceanic total dissolved inorganic carbon: a neural network approach. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 12, 1725–1743 (2020).

Keppler, L., Landschützer, P., Lauvset, S. K. & Gruber, N. Recent trends and variability in the oceanic storage of dissolved inorganic carbon. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 37, e2022GB007677 (2023).

Lehodey, P. et al. Optimization of a micronekton model with acoustic data. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 72, 1399–1412 (2015).

Rodgers, K. B., Lin, J. & Frölicher, T. L. Emergence of multiple ocean ecosystem drivers in a large ensemble suite with an Earth system model. Biogeosciences 12, 3301–3320 (2015).

Silvy, Y., Guilyardi, E., Sallée, J.-B. & Durack, P. J. Human-induced changes to the global ocean water masses and their time of emergence. Nat. Clim. Change 10, 1030–1036 (2020).

Sathyendranath, S., et al. An ocean-colour time series for use in climate studies: the experience of the ocean-colour climate change initiative (OC-CCI). Sensors 19, 4285 (2019).

von Schuckmann, K. et al. Copernicus Marine Service Ocean State Report, Issue 5. J. Oper. Oceanogr. 14, 1–185 (2021).

Eyring, V. et al. Overview of the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project Phase 6 (CMIP6) experimental design and organization. Geosci. Model Dev. 9, 1937–1958 (2016).

Fang, C., Wu, L. & Zhang, X. The impact of global warming on the Pacific Decadal Oscillation and the possible mechanism. Adv. Atmos. Sci. 31, 118–130 (2014).

Enfield, D. B., Mestas-Nuñez, A. M. & Trimble, P. J. The Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation and its relation to rainfall and river flows in the continental US. Geophys. Res. Lett. 28, 2077–2080 (2001).

Garcia-Soto, C. et al. An overview of ocean climate change indicators: sea surface temperature, ocean heat content, ocean pH, dissolved oxygen concentration, Arctic Sea ice extent, thickness and volume, sea level and strength of the AMOC. Front. Mar. Sci. 8, 642372 (2021).

Dangendorf, S. et al. Data-driven reconstruction reveals large-scale ocean circulation control on coastal sea level. Nat. Clim. Change 11, 514–520 (2021).

Sohail, T., Zika, J. D., Irving, D. B. & Church, J. A. Observed poleward freshwater transport since 1970. Nature 602, 617–622 (2022).

Hammersley, J. Monte Carlo Methods (Springer, 2013).

Kossin, J. P., Emanuel, K. A. & Camargo, S. J. Past and projected changes in western North Pacific tropical cyclone exposure. J. Clim. 29, 5725–5739 (2016).

Winsemius, H. C. et al. Disaster risk, climate change, and poverty: assessing the global exposure of poor people to floods and droughts. Environ. Dev. Econ. 23, 328–348 (2018).

François, B. & Vrac, M. Time of emergence of compound events: contribution of univariate and dependence properties. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 23, 21–44 (2023).

Tan, Z. et al. Codes reproductivity for observed large-scale and deep-reaching compound ocean state changes over the past 60 years. Code Ocean https://doi.org/10.24433/CO.6650239.v1 (2025).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant number 42261134536), the International Partnership Program of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (grant number 060GJHZ2024064MI), Asian Cooperation Fund (Z.T., L.C.), and the New Cornerstone Science Foundation through the XPLORER PRIZE (L.C.), the Youth Innovation Promotion Association of Chinese Academy of Sciences (L.C.), the ObsSea4Clim ‘Ocean observations and indicators for climate and assessments’ funded by the European Union, Horizon Europe Funding Programme for Research and Innovation under grant agreement number 101136548 (ObsSea4Clim contribution no. 20) (S.S., K.v.S., Z.T.) and the Ocean Cryosphere Exchanges in Antarctica: Impacts on Climate and the Earth System, OCEAN ICE, funded by the European Union, Horizon Europe Funding Programme for Research and Innovation under grant agreement number 101060452, 10.3030/101060452 (OCEAN ICE contribution number 44) (S.S., Z.T.). K.v.S. acknowledges financial support received from Mercator Ocean International, France. S.S. acknowledges financial support from the CNES-CNRS BioSWOT project (Les satellites au service de l’étude du plankton). L.B. acknowledges support from the CALIPSO project supported by Schmidt Sciences. We are thankful for the technical support of the National Large Scientific and Technological Infrastructure ‘Earth System Numerical Simulation Facility’ (https://cstr.cn/31134.02.EL). We thank G. Li and Y. Pan from the Institute of Atmospheric Physics, Chinese Academy of Sciences, for providing the CMIP6 post-processed data for our analysis. We thank L. Moreira (Nologin Oceanic Weather Systems, Spain), A. Miniere (Laboratoire de Météorologie Dynamique-ENS) and F. Reseghetti (Italian National Agency for New Technologies, Energy and Sustainable Economic Development, S. Teresa Research Center) for comments and feedback in the early stages of this study. We are grateful to K. Lyu (Xiamen University) for comments on the estimation of time of emergence (ToE) and F. Gues (Mercator Ocean international) for technical assistance with data analysis. We are also thankful to H. Wang (Aerospace Information Research Institute, Chinese Academy of Sciences) and J. Zhou (Chinese Academy of Natural Resources Economics, Ministry of Natural Resources) for their comments on the graphical visualizations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

K.v.S. and L.C. supervised this study. L.C., K.v.S. and Z.T. conceived this study. Z.T., L.C., K.v.S., L.B. and S.S. contributed to the methodology. Z.T. drafted the first manuscript and analysed the data. Z.T. prepared the figures. J.Z. and all authors contributed to the writing and reviewing of the manuscript, the funding acquisition and project administration.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Climate Change thanks Taimoor Sohail and the other, anonymous, reviewer for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Extended Data Fig. 1 The ToE (unit: year) of surface pH using different observational-based products.

(a) Copernicus: Global Ocean Surface Carbon113 and (b) Ocean SODA-ETHZ product115. Only acidification emergence is shown. (c) is the same as (a) and (b) but shows the global percentage of emergence as a function of the year, with the shading indicating the uncertainty range represented by the data uncertainty (see Methods). The reference period (baseline) is 1985-1989. The polar regions (beyond 60 N and 60S) are not examined due to lack of data. Basemap generated with M_Map (www.eoas.ubc.ca/~rich/map.html).

Extended Data Fig. 2 The temperature ToE (unit: year) in different layers using the IAP temperature gridded product103.