Abstract

While of critical importance for coastal communities, Antarctica’s future sea-level contribution remains highly uncertain. This uncertainty largely stems from the complex interaction between the ocean and the ice shelves, which is both difficult to observe and model. To better understand and constrain land-ice response to reduced buttressing exerted by ice shelves, efforts are needed to fully comprehend basal melt rates and their impact on ice shelf weakening and retreat. Here we present high-resolution basal melt maps (50 m) of vulnerable ice shelves based on a combination of stereo imagery and satellite altimetry, revealing pronounced channelized melting patterns whose melt rates were previously substantially underestimated (42–50%), which could result in faster channel breakthrough. Accurately simulating small-scale dynamics in ice-sheet models remains challenging but is essential for accurate sea-level rise projections.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$32.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $21.58 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

The derived channel product and BURGEE basal melt rates are publicly available (https://doi.org/10.4121/4e2ba9a9-7b1b-4837-b52d-036f8c876e67)46. REMA strips and mosaics are available from the Polar Geosptaital Center (https://www.pgc.umn.edu/data/rema/), CryoSat-2 data are available from the European Space Agency (https://earth.esa.int/eogateway/documents/20142/37627/CryoSat-Baseline-D-Product-Handbook.pdf) and MEaSUREs ITS_LIVE velocities and BedMachine v.3 are both available from NASA National Snow and Ice Data Center (https://doi.org/10.5067/6II6VW8LLWJ7 and https://nsidc.org/data/NSIDC-0756/versions/3). The ref. 8 basal melt product is available via Zenodo at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8052519 (ref. 47) and the melt product from ref. 7 is available from UC San Diego (https://doi.org/10.6075/J04Q7SHT). The ice shelf damage product is available from the 4TU research data repository (https://doi.org/10.4121/911e8799-f0dc-42e3-82b4-766ad680a71e.v2). The polynyas and manually derived channels from ref. 12, the basal melt rates of Pine Island from ref. 9 and the model results of the impact of secondary flow on channel breakthrough from ref. 17 are available from the respective authors on request.

Code availability

The BURGEE code (v.1 and v.2) is publicly available (https://github.com/aszinck/BURGEE)48 and code for the channel analysis and deriving channels is available via Zenodo at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17671626 (ref. 49).

References

Pattyn, F. et al. The uncertain future of the Antarctic Ice Sheet. Science 367, 1331–1335 (2020).

IPCC. Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis (eds Masson-Delmotte, V. et al.) (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2023).

Bamber, J. L. et al. Ice sheet and climate processes driving the uncertainty in projections of future sea level rise: findings from a structured expert judgement approach. Earth’s Future 10, e2022EF002772 (2022).

van de Wal, R. S. W. et al. A high end estimate of sea level rise for practitioners. Earth’s Future 10, e2022EF002751 (2022).

Pattyn, F. et al. The Greenland and Antarctic ice sheets under 1.5 °C global warming. Nat. Clim. Change 8, 1053–1061 (2018).

Naughten, K. A. et al. Unavoidable future increase in West Antarctic ice-shelf melting over the twenty-first century. Nat. Clim.Change 13, 1222–1228 (2023).

Adusumilli, S. et al. Interannual variations in meltwater input to the Southern Ocean from Antarctic ice shelves. Nat. Geosci. 13, 616–620 (2020).

Davison, B. J. et al. Annual mass budget of Antarctic ice shelves from 1997 to 2021. Sci. Adv.9, eadi0186 (2023).

Shean, D. E. et al. Ice shelf basal melt rates from a high-resolution digital elevation model (DEM) record for Pine Island Glacier, Antarctica. Cryosphere 13, 2633–2656 (2019).

Zinck, A.-S. P. et al. Unveiling spatial variability within the Dotson melt channel through high-resolution basal melt rates from the reference elevation model of Antarctica. Cryosphere 17, 3785–3801 (2023).

Gourmelen, N. et al. Channelized melting drives thinning under a rapidly melting Antarctic ice shelf. Geophys. Res. Lett. 44, 9796–9804 (2017).

Alley, K. E. et al. Impacts of warm water on Antarctic ice shelf stability through basal channel formation. Nat. Geosci. 9, 290–293 (2016).

Alley, K. E. et al. The role of channelized basal melt in ice-shelf stability: recent progress and future priorities. Ann. Glaciol. 63, 18–22 (2022).

Alley, K. E. et al. Evolution of sub-ice-shelf channels reveals changes in ocean-driven melt in West Antarctica. J. Glaciol. 70, e50 (2024).

Chartrand, A. M. et al. Basal channel evolution on the Getz Ice Shelf, West Antarctica. J. Geophys. Res. Earth Surf. 125, e2019JF005293 (2020).

Chartrand, A. M. et al. Thwaites Glacier thins and retreats fastest where ice-shelf channels intersect its grounding zone. Cryosphere 18, 4971–4992 (2024).

Wearing, M. G. et al. Ice shelf basal melt channels stabilized by secondary flow. Geophys. Res. Lett. 48, e2021GL094872 (2021).

Humbert, A. et al. On the evolution of an ice shelf melt channel at the base of Filchner ice shelf, from observations and viscoelastic modeling. Cryosphere 16, 4107–4139 (2022).

Dow, C. F. et al. Basal channels drive active surface hydrology and transverse ice shelf fracture. Sci. Adv. 4, eaao7212 (2018).

Seroussi, H. et al. ISMIP6 Antarctica: a multi-model ensemble of the Antarctic ice sheet evolution over the 21st century. Cryosphere 14, 3033–3070 (2020).

Gourmelen, N. et al. CryoSat-2 swath interferometric altimetry for mapping ice elevation and elevation change. Adv. Space Res. 62, 1226–1242 (2018).

Lhermitte, S. et al. Damage accelerates ice shelf instability and mass loss in Amundsen Sea Embayment. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 117, 24735–24741 (2020).

Kachuck, S. B. et al. Simulating ice-shelf extent using damage mechanics. J. Glaciol. 68, 987–988 (2022).

Alley, K. E. et al. Troughs developed in ice-stream shear margins precondition ice shelves for ocean-driven breakup. Sci. Adv. 5, eaax2215 (2019).

Mankoff, K. D. et al. The role of Pine Island Glacier ice shelf basal channels in deep-water upwelling, polynyas and ocean circulation in Pine Island Bay, Antarctica. Ann. Glaciol. 53, 123–128 (2012).

Winstrup, M. et al. Prodem: an annual series of summer dems (2019 through 2022) of the marginal areas of the greenland ice sheet. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 16, 5405–5428 (2024).

de Roda Husman, S. et al. A high-resolution record of surface melt on Antarctic ice shelves using multi-source remote sensing data and deep learning. Remote Sens. Environ. 301, 113950 (2024).

Lambert, E. et al. Modelling Antarctic ice shelf basal melt patterns using the one-layer Antarctic model for dynamical downscaling of ice-ocean exchanges (LADDIE v1.0). Cryosphere 17, 3203–3228 (2023).

Sergienko, O. V. Basal channels on ice shelves. J. Geophys. Res. Earth Surf. 118, 1342–1355 (2013).

Drews, R. Evolution of ice-shelf channels in Antarctic ice shelves. Cryosphere 9, 1169–1181 (2015).

Bassis, J. et al. Evolution of basal crevasses links ice shelf stability to ocean forcing. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 409, 203–211 (2015).

van Westen, R. M. et al. Ocean eddies strongly affect global mean sea-level projections. Sci. Adv. 7, eabf1674 (2021).

van Wessem, J. M. et al. Modelling the climate and surface mass balance of polar ice sheets using RACMO2—Part 2: Antarctica (1979–2016). Cryosphere 12, 1479–1498 (2018).

Veldhuijsen, S. B. M. et al. Characteristics of the 1979–2020 Antarctic firn layer simulated with IMAU-FDM v1.2A. Cryosphere 17, 1675–1696 (2023).

Gardner, A. et al. MEaSUREs ITS_LIVE Regional Glacier and Ice Sheet Surface Velocities version 1, https://nsidc.org/data/nsidc-0776/versions/1 (NASA, 2022).

Chartrand, R. Numerical Differentiation of Noisy, Nonsmooth, Multidimensional Data 244–248 (IEEE, 2017).

Pavlis, N. K. et al. The development and evaluation of the Earth Gravitational Model 2008 (EGM2008). J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 117, B04406 (2012).

Gagliardini, O. et al. Capabilities and performance of Elmer/Ice, a new-generation ice sheet model. Geosci. Model Dev. 6, 1299–1318 (2013).

Cuffey, K. M. & Paterson, W. The Physics of Glaciers 4th edn (Elsevier, 2010).

Howat, I. M. et al. The reference elevation model of Antarctica. Cryosphere 13, 665–674 (2019).

Schmidt, B. E. et al. Heterogeneous melting near the Thwaites Glacier grounding line. Nature 614, 471–478 (2023).

Wåhlin, A. et al. Swirls and scoops: ice base melt revealed by multibeam imagery of an Antarctic ice shelf. Sci. Adv. 10, eadn9188 (2024).

Morlighem, M. MEaSUREs BedMachine Antarctica version 3, https://nsidc.org/data/NSIDC-0756/versions/3 (NASA, 2022).

Lomb, N. R. Least-squares frequency analysis of unequally spaced data. Astrophys. Space Sci. 39, 447–462 (1976).

Scargle, J. D. Studies in astronomical time series analysis. II—Statistical aspects of spectral analysis of unevenly spaced data. Astrophys. J. 263, 835–853 (1982).

Zinck, A.-S. et al. Dataset belonging to the article: Exposure to underestimated channelized melt in Antarctic Ice Shelves. 4TU.ResearchData https://doi.org/10.4121/4e2ba9a9-7b1b-4837-b52d-036f8c876e67 (2024).

Davison, B. Data and code for: “Annual mass budget of Antarctic ice shelves from 1997 to 2021” [Data set]. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8052519 (2023).

Zinck, A.-S. BURGEE. GitHub https://github.com/aszinck/BURGEE (2023).

Zinck, A.-S. Code belonging to the article ‘Channelized melt beneath Antarctic ice shelves previously underestimated’. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17671626 (2025).

Scambos, T. et al. MODIS-based Mosaic of Antarctica (MOA) data sets: continent-wide surface morphology and snow grain size. Remote Sens. Environ. 111, 242–257 (2007).

Matsuoka, K. et al. Quantarctica, an integrated mapping environment for antarctica, the southern ocean, and sub-antarctic islands. Environ. Model. Softw. 140, 105015 (2021).

Acknowledgements

This study is a part of the HiRISE project funded by the Dutch Research Council (NWO, no. OCENW.GROOT.2019.091).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The research was designed by A.-S.P.Z., S.L. and B.W. and carried out by A.-S.P.Z. M.G.W. made substantial contributions to the interpretations of the results. The writing of the paper was led by A.-S.P.Z. with input from all authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

M.G.W. is employed by European Space Agency (ESA) who are responsible for satellite radar altimeter CryoSat-2. ESA had no involvement in the study and did not provide funding. The rest of the authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Climate Change thanks Winnie Chu, Tyler Pelle and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Extended Data Fig. 1 Basal melt rate comparison.

Basal melt rates from this study are marked with 1 and melt rates from Adusumilli7 are marked with 2. Panels a–i show the individual ice shelves as marked in the bottom legend. The Ninnis ice shelf (g) is not covered by Adusumilli7. The black line denotes the BedMachine V3 grounding line43. The circles denote total ice-shelf wide basal melt rate in Gt/yr, only considering areas covered by both BURGEE, Adusumilli7, and Davison8. Note that, for example, different acquisition times (Suppl. Fig. 9) and radar penetration depth, can cause visible seams in the BURGEE melt maps (Supplementary Information S1). All panels use MODIS50 as background imagery and are generated using Quantarctica51. The Quantarctica package is published under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

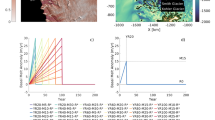

Extended Data Fig. 2 Basal melt rate distributions.

Basal melt rate probability density functions of Adusumilli7, Davison8, and BURGEE melt rates, the latter at the original 50 m posting and interpolated (nearest-neighbour) onto the 500 m grid used in Adusumilli7. Distributions are grouped by different ice shelf thickness sections based on BedMachine V343 and only areas covered by all melting products are considered (thus excluding Ninnis Ice Shelf). In the lower subpanels, the thick, vertical black line represents the median melt rate, the solid box ranges from the first to the third quartile, and the whiskers extend the box to 1.5x the inter-quartile range. The total area considered is 19,539 km2, which in pixels correspond to 19,539 for Davison8, 84,382 for Adusumilli7 and BURGEE 500 m, and 7,801,438 for BURGEE 50 m.

Extended Data Fig. 3 Ice thickness and basal channels.

a–i, BedMachineV3 ice thicknesses43 overlaid with detected channels (’all channels’) of Pine Island (a), Thwaites (b), Dotson/Crosson (c), Drygalski (d), Cook (e), Mertz (f), Ninnis (g), Moscow University (h) and Totten (i) ice shelves. All detected channels are further sub-categorized into slope-corrected channels which represent channels with maximum slopes < 15°. Only a subset of the slope-corrected channels is studied (‘studied channels`), namely those channels where the 90% percentile melt rate is > 10 m/yr, as they are considered to be ”active” melt-channels. Persistent polynya locations from ref. 24 are marked by red diamonds. Lettering corresponds to Extended Data Fig. 1. The solid black line denotes the BedMachine V3 grounding line43. All panels use MODIS50 as background imagery and are generated using Quantarctica51. The Quantarctica package is published under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Extended Data Fig. 4 Channel peak melt rates and normalized breakthrough times (NBTs).

a) Channel peak melt rates compared to ice shelf thicknesses outside the channels. Dashed lines connect peak melt rates from the different products of the same channel. Filled markers indicate channels with a characteristic channel width of 1.5-3.5 km, which is comparable to the characteristic channel width (2.5 km) used to obtain NBTs17. Unfilled markers represent all other channels (only narrower). Dashed square marks the zoomed-in region in b). In the lower subpanel, the thick, vertical black line represents the median peak melt rate, the solid box ranges from the first to the third quartile, and the whiskers extend the box to 1.5x the inter-quartile range. The box plots are based on 88, 107, and 108 (sub-)channels for Adusumilli7, Davison8, and BURGEE, respectively. b) Zoom-in of channel peak melt rates compared to ice shelf thicknesses outside the channels and NBTs obtained from ref. 17. An NBT of 1 is when linear breakthrough and breakthrough with secondary flow are equal. Linear breakthrough times are shown in Suppl. Fig. 7.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figs. 1–16, Supplementary Table 1 and Supplementary Discussions 1 and 2.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Zinck, AS.P., Lhermitte, S., Wearing, M.G. et al. Channelized melt beneath Antarctic ice shelves previously underestimated. Nat. Clim. Chang. (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-025-02537-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-025-02537-1