Abstract

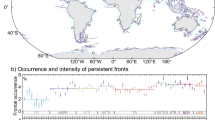

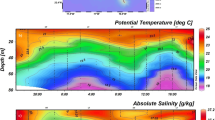

Ocean fronts are critical features that influence marine ecosystems and can affect climate at both regional and global scales. In many regions, fronts enhance vertical mixing and advection, increasing nutrient supply, which can stimulate primary production and modulate air–sea CO2 fluxes. However, a global perspective on the impacts of changing ocean fronts on primary production and air–sea CO2 exchange is still lacking. Here using satellite observations (2003–2024) and supplementary reanalysis data at higher latitudes (2003–2024), we identify areas with the richest frontal activity and the fastest-changing frontal properties. We find that 72% of global ocean CO2 uptake occurs in key frontal areas. Trends in sea surface chlorophyll concentration and ocean CO2 uptake closely track changes in local frontal activity. Our results indicate that ocean fronts play a central role in regulating the global carbon cycle by influencing the biological component of air–sea CO2 fluxes.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$32.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $21.58 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

NASA MODIS-Aqua daily SST data (MODIS_AQUA_L3_SST_MID-IR_DAILY_4KM_NIGHTTIME_V2019.0) are distributed by NASA Physical Oceanography Distributed Active Archive Center (https://podaac.jpl.nasa.gov/, https://doi.org/10.5067/MODAM-1D4N9)75. MODIS-Aqua monthly chlorophyll a concentration data (Aqua/MODIS level 3 mapped chlorophyll data version 2022) are available from NASA Ocean Color (https://oceancolor.gsfc.nasa.gov/, https://doi.org/10.5067/AQUA/MODIS/L3M/CHL/2022.0)76. C3S daily reprocessed SST data (C3S-GLO-SST-L4-REP-OBS-SST) are available from the EU Copernicus Marine Service (https://marine.copernicus.eu/, https://doi.org/10.48670/moi-00169)77. Model-based CO2 flux data are available via Zenodo at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10222483 (ref. 78) and monthly pCO2 data can also be downloaded from the EU Copernicus Marine Service (https://marine.copernicus.eu/, https://doi.org/10.48670/moi-00047)79. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

The Cayula–Cornillon algorithm (frontal detection method) was applied using the module ‘Oceanographic Analysis’ embedded in the Marine Geospatial Ecology Tools (MGET), v.0.8a75, released on 8 April 2021, which integrates with ArcGIS. The MGET toolbox67 is available at Duke Marine Geospatial Ecology Lab (https://mgel.env.duke.edu). Trend and significance analyses were performed using code published by Martínez-Moreno et al.80, available via Zenodo at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.4458783 and https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.4458776 (refs. 81,82). All Jupyter Notebook scripts used to produce figures are available and regularly updated via Zenodo at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.13943854) (ref. 83).

References

Fedorov, K. N. The Physical Nature and Structure of Oceanic Fronts Vol. 333 (Springer, 1986).

Cromwell, T. & Reid, J. L. Jr A study of oceanic fronts. Tellus 8, 94–101 (1956).

Garvine, R. W. Dynamics of small-scale oceanic fronts. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 4, 557–569 (1974).

Belkin, I. M., Cornillon, P. C. & Sherman, K. Fronts in large marine ecosystems. Prog. Oceanogr. 81, 223–236 (2009).

Woodson, C. B. & Litvin, S. Y. Ocean fronts drive marine fishery production and biogeochemical cycling. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 112, 1710–1715 (2015).

Acha, E. M., Piola, A., Iribarne, O. & Mianzan, H. Ecological Processes at Marine Fronts: Oases in the Ocean (Springer, 2015).

Arbilla, L. A., Ruiz-Etcheverry, L. A., López-Abbate, C. & Kahl, L. C. CO2 sink and source zones delimited by marine fronts in the Drake Passage. Prog. Oceanogr. 223, 103246 (2024).

Bost, C.-A. et al. The importance of oceanographic fronts to marine birds and mammals of the southern oceans. J. Mar. Syst. 78, 363–376 (2009).

De Verneil, A., Franks, P. & Ohman, M. Frontogenesis and the creation of fine-scale vertical phytoplankton structure. J. Geophys. Res. 124, 1509–1523 (2019).

Bianchi, A. A. et al. Annual balance and seasonal variability of sea–air CO2 fluxes in the Patagonia Sea: their relationship with fronts and chlorophyll distribution. J. Geophys. Res. 114, C03018 (2009).

Franco, B. C., Ruiz-Etcheverry, L. A., Marrari, M., Piola, A. R. & Matano, R. Climate change impacts on the Patagonian shelf break front. Geophys. Res. Lett. 49, e2021GL096513 (2022).

Gangrade, S. & Franks, P. J. Phytoplankton patches at oceanic fronts are linked to coastal upwelling pulses: observations and implications in the California Current System. J. Geophys. Res. 128, e2022JC019095 (2023).

Ramond, P. et al. Phytoplankton taxonomic and functional diversity patterns across a coastal tidal front. Sci. Rep. 11, 2682 (2021).

DeVries, T. The ocean carbon cycle. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 47, 317–341 (2022).

de La Rocha, C. L. & Passow, U. in Treatise on Geochemistry 2nd edn, Vol. 8 (eds Holland, H. D. & Turekian, K. K.) 93–122 (Elsevier, 2014).

Teng, H., Masutani, S., Kinoshita, C. & Nihous, G. Solubility of CO2 in the ocean and its effect on CO2 dissolution. Energy Convers. Manag. 37, 1029–1038 (1996).

Stukel, M. R. et al. Mesoscale ocean fronts enhance carbon export due to gravitational sinking and subduction. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 114, 1252–1257 (2017).

Gattuso, J.-P. et al. Contrasting futures for ocean and society from different anthropogenic CO2 emissions scenarios. Science 349, aac4722 (2015).

Sarmiento, J. L., Hughes, T. M., Stouffer, R. J. & Manabe, S. Simulated response of the ocean carbon cycle to anthropogenic climate warming. Nature 393, 245–249 (1998).

Friedlingstein, P. et al. Global carbon budget 2023. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 15, 5301–5369 (2023).

Couespel, D., Lévy, M. & Bopp, L. Stronger oceanic CO2 sink in eddy-resolving simulations of global warming. Geophys. Res. Lett. 51, e2023GL106172 (2024).

Castelao, R. M., Mavor, T. P., Barth, J. A. & Breaker, L. C. Sea surface temperature fronts in the California Current System from geostationary satellite observations. J. Geophys. Res. 111, C09026 (2006).

Kahru, M., Di Lorenzo, E., Manzano-Sarabia, M. & Mitchell, B. G. Spatial and temporal statistics of sea surface temperature and chlorophyll fronts in the California Current. J. Plankton Res. 34, 749–760 (2012).

Oerder, V., Bento, J. P., Morales, C. E., Hormazabal, S. & Pizarro, O. Coastal upwelling front detection off central Chile (36.5–37° S) and spatio-temporal variability of frontal characteristics. Remote Sens. 10, 690 (2018).

Saldías, G. S. & Lara, C. Satellite-derived sea surface temperature fronts in a river-influenced coastal upwelling area off central–southern Chile. Reg. Stud. Mar. Sci. 37, 101322 (2020).

Xi, J., Wang, Y., Feng, Z., Liu, Y. & Guo, X. Variability and intensity of the sea surface temperature front associated with the Kuroshio extension. Front. Mar. Sci. 9, 836469 (2022).

Yang, K., Fischer, A. M. & Govekar, P. Trends of satellite-derived thermal fronts in the southeast and southwest of Australia between 1993 and 2019. Ocean Sci. J. 59, 14 (2024).

Mauzole, Y. Objective delineation of persistent SST fronts based on global satellite observations. Remote Sens. Environ. 269, 112798 (2022).

Yang, K., Meyer, A., Strutton, P. G. F. & Fischer, A. M. Global trends of fronts and chlorophyll in a warming ocean. Commun. Earth Environ. 4, 489 (2023).

Xing, Q., Yu, H. & Wang, H. Global mapping and evolution of persistent fronts in large marine ecosystems over the past 40 years. Nat. Commun. 15, 4090 (2024).

Obenour, K. M. Temporal Trends in Global Sea Surface Temperature Fronts. MSc thesis, Univ. Rhode Island (2013).

Hammond, M. L., Beaulieu, C., Henson, S. A. & Sahu, S. K. Regional surface chlorophyll trends and uncertainties in the global ocean. Sci. Rep. 10, 15273 (2020).

Gregg, W. W., Rousseaux, C. S. & Franz, B. A. Global trends in ocean phytoplankton: a new assessment using revised ocean colour data. Remote Sens. Lett. 8, 1102–1111 (2017).

Henson, S. A., Cael, B., Allen, S. R. & Dutkiewicz, S. Future phytoplankton diversity in a changing climate. Nat. Commun. 12, 5372 (2021).

Bianchi, A. A. et al. Vertical stratification and air–sea CO2 fluxes in the Patagonian shelf. J. Geophys. Res.110, C07003 (2005).

Chapman, C. C., Lea, M.-A., Meyer, A., Sallée, J.-B. & Hindell, M. Defining Southern Ocean fronts and their influence on biological and physical processes in a changing climate. Nat. Clim. Change 10, 209–219 (2020).

Meijers, A., Bindoff, N. & Rintoul, S. Frontal movements and property fluxes: contributions to heat and freshwater trends in the Southern Ocean. J. Geophys. Res. 116, C08024 (2011).

Mauzole, Y., Torres, H. & Fu, L. L. Patterns and dynamics of SST fronts in the California Current System. J. Geophys. Res. 125, e2019JC015499 (2020).

Yamaguchi, R. & Suga, T. Trend and variability in global upper-ocean stratification since the 1960s. J. Geophys. Res. 124, 8933–8948 (2019).

Wu, L. et al. Enhanced warming over the global subtropical western boundary currents. Nat. Clim. Change 2, 161–166 (2012).

Yang, H. et al. Poleward shift of the major ocean gyres detected in a warming climate. Geophys. Res. Lett. 47, e2019GL085868 (2020).

Hwang, B. & Landy, J. Impacts of climate change on Arctic sea ice. MCCIP Sci. Rev. 2020, 208–227 (2020).

Manucharyan, G. E. & Thompson, A. F. Heavy footprints of upper-ocean eddies on weakened Arctic sea ice in marginal ice zones. Nat. Commun. 13, 2147 (2022).

de Steur, L., Sumata, H., Divine, D. V., Granskog, M. A. & Pavlova, O. Upper ocean warming and sea ice reduction in the East Greenland Current from 2003 to 2019. Commun. Earth Environ. 4, 261 (2023).

Rantanen, M. et al. The Arctic has warmed nearly four times faster than the globe since 1979. Commun. Earth Environ. 3, 168 (2022).

Smeed, D. A. et al. The North Atlantic Ocean is in a state of reduced overturning. Geophys. Res. Lett. 45, 1527–1533 (2018).

Wang, C. et al. Recent slowing of Arctic sea ice melt tied to multidecadal NAO variability. Nat. Commun. 16, 8504 (2025).

Zhao, L., Zhang, J., Yang, D., Cai, S. & Zhong, R. Seasonal variability of SST fronts in the southern ocean south of 60° S: the relationship with sea ice. Environ. Res. Commun. 7, 075009 (2025).

Sallée, J., Speer, K. & Morrow, R. Response of the Antarctic Circumpolar Current to atmospheric variability. J. Clim. 21, 3020–3039 (2008).

Oelerich, R. et al. Stirring across the Antarctic Circumpolar Current’s southern boundary at the prime meridian, Weddell Sea. Ocean Sci. 19, 1465–1482 (2023).

Swart, S. et al. Submesoscale fronts in the Antarctic marginal ice zone and their response to wind forcing. Geophy. Res. Lett. 47, e2019GL086649 (2020).

Woodson, C. et al. Coastal fronts set recruitment and connectivity patterns across multiple taxa. Limnol. Oceanogr. 57, 582–596 (2012).

Ferrari, R. A frontal challenge for climate models. Science 332, 316–317 (2011).

D’asaro, E., Lee, C., Rainville, L., Harcourt, R. & Thomas, L. Enhanced turbulence and energy dissipation at ocean fronts. Science 332, 318–322 (2011).

Guo, M. et al. Efficient biological carbon export to the mesopelagic ocean induced by submesoscale fronts. Nat. Commun. 15, 580 (2024).

Kelly, T. B. et al. Lateral advection supports nitrogen export in the oligotrophic open-ocean Gulf of Mexico. Nat. Commun. 12, 3325 (2021).

Kulk, G. et al. Primary production, an index of climate change in the ocean: satellite-based estimates over two decades. Remote Sens. 12, 826 (2020).

Lester, C. W., Wagner, T. J. W., McNamara, D. E. & Cape, M. R. The influence of meltwater on phytoplankton blooms near the sea-ice edge. Geophys. Res. Lett. 48, e2020GL091758 (2021).

Hopwood, M. J. et al. Non-linear response of summertime marine productivity to increased meltwater discharge around Greenland. Nat. Commun. 9, 3256 (2018).

Weiss, R. F. Carbon dioxide in water and seawater: the solubility of a non-ideal gas. Mar. Chem. 2, 203–215 (1974).

Gruber, N. et al. Trends and variability in the ocean carbon sink. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 4, 119–134 (2023).

Baynes, K. Data Processing Levels (NASA, 2025).

Marshall, G. J., Rees, W. G. & Dowdeswell, J. A. Limitations imposed by cloud cover on multitemporal visible band satellite data sets from polar regions. Ann. Glaciol. 17, 113–120 (1993).

Yu, S., Bai, Y., He, X., Gong, F. & Li, T. A new merged dataset of global ocean chlorophyll-a concentration for better trend detection. Front. Mar. Sci. 10, 1051619 (2023).

Cayula, J.-F. & Cornillon, P. Edge detection algorithm for SST images. J. Atmos. Ocean. Technol. 9, 67–80 (1992).

Belkin, I. M. Remote sensing of ocean fronts in marine ecology and fisheries. Remote Sens. 13, 883 (2021).

Roberts, J. J., Best, B. D., Dunn, D. C., Treml, E. A. & Halpin, P. N. Marine Geospatial Ecology Tools: an integrated framework for ecological geoprocessing with ArcGIS, Python, R, MATLAB, and C+. Environ. Model. Softw. 25, 1197–1207 (2010).

Takahashi, T. et al. Global sea–air CO2 flux based on climatological surface ocean pCO2, and seasonal biological and temperature effects. Deep-Sea Res. II 49, 1601–1622 (2002).

Sen, P. K. Estimates of the regression coefficient based on Kendall’s tau. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 63, 1379–1389 (1968).

Theil, H. A rank-invariant method of linear and polynomial regression analysis. Proc. K. Ned. Akad. Wet. 53, 386–392 (1950).

Yue, S. & Wang, C. The Mann–Kendall test modified by effective sample size to detect trend in serially correlated hydrological series. Water Res. Manag. 18, 201–218 (2004).

Spearman, C. The proof and measurement of association between two things. Am. J. Psychol. 100, 441–471 (1987).

Ackerman, S. A. et al. Discriminating clear sky from clouds with MODIS. J. Geophys. Res. 103, 32141–32157 (1998).

Medhaug, I., Stolpe, M. B., Fischer, E. M. & Knutti, R. Reconciling controversies about the ‘global warming hiatus’. Nature 545, 41–47 (2017).

MODIS Aqua Level 3 SST MID-IR Daily 4km Nighttime V2019.0 (NASA, accessed 22 March 2024); https://doi.org/10.5067/MODAM-1D4N9

Aqua MODIS Level-3 Global Mapped Chlorophyll (CHL) Data, version 2022.0 (NASA, accessed 9 September 2025); https://doi.org/10.5067/AQUA/MODIS/L3M/CHL/2022.0

ESA SST CCI and C3S Reprocessed Sea Surface Temperature Analyses (Copernicus Marine Service, accessed 23 July 2024); https://doi.org/10.48670/moi-00169

Hauck, J., Landschützer, P., Mayot, N. & Jersild, A. Global Carbon Budget 2023, surface ocean fugacity of CO2 (fCO2) and air–sea CO2 flux of individual global ocean biogechemical models and surface ocean fCO2-based data-products. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10222483 (2023).

Surface Ocean Carbon Fields (Copernicus Marine Service, accessed 4 September 2024); https://doi.org/10.48670/moi-00047

Martínez-Moreno, J. et al. Global changes in oceanic mesoscale currents over the satellite altimetry record. Nat. Clim. Change 11, 397–403 (2021).

Martínez Moreno, J. & Constantinou, N. C. josuemtzmo/EKE_SST_trends: EKE_SST_trends: Jupyter notebooks (Python) used to compute trends of Eddy kinetic energy and sea surface temperature. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.4500152 (2021).

Martínez Moreno, J. & Constantinou, N. C. josuemtzmo/xarrayMannKendall: Mann Kendall significance test implemented in xarray. (v.1.0.1). Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.4458780 (2021).

Yang, K., Meyer, A., Le, P. T. D., Strutton, P. G. & Fischer, A. M. Global trends in ocean fronts: impacts on air–sea CO2 flux and chlorophyll concentrations—Jupyter notebooks (Python) used to reproduce figures. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.13943854 (2024).

Acknowledgements

K.Y. acknowledges financial support from the University of Tasmania and the China Scholarship Council (CSC) of the Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China (grant no. 202006330006). K.Y., A.M. and P.G.S. were supported by the Australian Research Council (ARC) Centre of Excellence for Climate Extremes (CLEX; ARC grant no. CE170100023) and Centre of Excellence for 21st Century Weather (ARC grant no. CE230100012). A.M. was also supported by the Australian Research Council Discovery Early Career Researcher Award project DE200100414. We are grateful for the freely available MODIS SST and chlorophyll a concentration data products from NASA OBPG and the reprocessed SST product from the EU Copernicus Marine Service. We acknowledge the Global Carbon Project, which produced the Global Carbon Budget with the CO2 flux estimates used in this study and we thank the ocean modelling and fCO2-mapping groups for making their model and fCO2-product outputs available. We also thank J. Hauck from the Alfred Wegener Institute (AWI) for providing suggestions about the Global Carbon Budget data product. K.Y. also acknowledges the State Key Laboratory of Marine Environmental Science (MEL) and the College of Ocean and Earth Sciences at Xiamen University (XMU), China, for providing support, including short-term funding and access to facilities, during the later stages of this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

K.Y. designed, performed the experiment, wrote the code, analysed the data and wrote the paper. A.M. designed the experiment and contributed to writing the paper. P.T.D.L. analysed data and contributed to writing the paper. P.G.S. and A.M.F. contributed to writing the paper. All authors discussed the results and implications and commented on the paper at all stages.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Climate Change thanks Prasanjit Dash, Yackar Mauzole and Peter Miller for their contributions to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Extended Data Fig. 1 Temporal coverage of Aqua-MODIS daily sea surface temperature (SST) data from 2003 to 2024.

Hatched areas indicate areas with more than 80% data availability. Only grid cells within 60°N–60°S were included in the main analysis.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Spatial distribution of surface partial pressure of CO2 (pCO2) in seawater.

Panel a: estimated non-thermal pCO2 for 2024, with key frontal areas (black contours), intensifying frontal areas (red contours), and declining frontal areas (blue contours). Panel b: area-averaged non-thermal pCO2 for 2024. Non-thermal pCO2 is the temperature-corrected component of seawater pCO2, isolating the influence of biological activity, vertical mixing, and other non-thermal processes. Lower values indicate enhanced biological CO2 uptake or weakened upwelling of CO2-rich waters, whereas higher values reflect stronger non-thermal CO2 sources.

Extended Data Fig. 3 Temporal changes in key, intensifying, and declining frontal areas.

Panel a: annual area (million km2) of the key frontal areas with the corresponding linear trend (dashed line; Theil-Sen). Panel b: annual area (million km2) of intensifying (red) and declining (blue) frontal areas, computed using a 5-year rolling window, with their linear trends (dashed lines; Theil-Sen). Trend slopes, reported as % per year, quantify the average relative change in area per year, referenced to the first year (panel a) or the first 5-year rolling window (panel b). None of the estimated trends are statistically significant.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figs. 1 and 2, Table 1 and discussion.

Source data

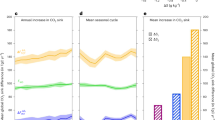

Source Data Fig. 2

Statistical source data; slope data.

Source Data Fig. 3

Zonal mean data.

Source Data Fig. 4

Zonal mean data.

Source Data Fig. 5

Zonal mean data; statistical source data; slope data.

Source Data Fig. 6

Area data; statistical source data; slope data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 3

Time series data.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Yang, K., Meyer, A., Le, P.T.D. et al. Global trends in ocean fronts and impacts on the air–sea CO2 flux and chlorophyll concentrations. Nat. Clim. Chang. (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-025-02538-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-025-02538-0