Abstract

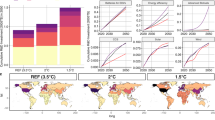

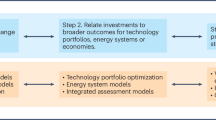

Accelerating energy innovation for decarbonization hinges on public investment in research, development and demonstration (RD&D). Here we examine the evolution and variation of public energy RD&D funding and institutions and associated drivers across eight major economies, including China and India (2000–2018). The share of new clean energy grew at the expense of nuclear, while the fossil fuel RD&D share remained stable. Governments created new institutions but experimented only marginally with novel designs that bridge lab to market to accelerate commercialization. In theory, crisis, cooperation and competition can be drivers of change. We find that cooperation in Mission Innovation is associated with punctuated change in clean-energy RD&D growth, and clean tech competition with China is associated with gradual change. Stimulus spending after the financial crisis, instead, boosted fossil and nuclear only. Looking ahead, global coopetition—the interplay of RD&D cooperation and clean tech competition—offers opportunities for accelerating energy innovation to meet climate goals.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$32.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 digital issues and online access to articles

$119.00 per year

only $9.92 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

We use two datasets: the first is an energy RD&D funding dataset that includes bottom-up data for China and India and IEA countries and the second is an inventory of 57 public energy innovation institutions related to decarbonization across the M8. Funding data for IEA countries (France, Germany, Japan, South Korea, United Kingdom and United States) are available from the IEA Energy Technologies RD&D database. Funding data for China and India are available as Supplementary Data 1. The institutional data are not currently publicly available due to additional ongoing analysis of the original dataset by the authors but are available upon reasonable request.

References

Energy Technology Perspectives 2020: Special Report on Clean Energy Innovation (International Energy Agency, 2020).

Cunliff, C. & Hart, D. M. Global Energy Innovation Index: National Contributions to the Global Clean Energy Innovation System (Information Technology & Innovation Foundation, 2019).

Mowery, D. C., Nelson, R. R. & Martin, B. R. Technology policy and global warming: why new policy models are needed (or why putting new wine in old bottles won’t work). Res. Policy 39, 1011–1023 (2010).

Marangoni, G. & Tavoni, M. The clean energy R&D strategy for 2 °C. Clim. Change Econ. 5, 1440003 (2014).

Anadon, L. D., Baker, E. & Bosetti, V. Integrating uncertainty into public energy research and development decisions. Nat. Energy 2, 17071 (2017).

Nemet, G. F., Zipperer, V. & Kraus, M. The valley of death, the technology pork barrel, and public support for large demonstration projects. Energy Policy 119, 154–167 (2018).

Anadon, L. D., Bunn, M. & Narayanamurti, V. Transforming US Energy Innovation (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2014).

Grübler, A., Nakićenović, N. & Victor, D. G. Modeling technological change: implications for the global environment. Annu. Rev. Energy Env. 24, 545–569 (1999).

Committee on Prospering in the Global Economy of the 21st Century Rising Above the Gathering Storm: Energizing and Employing America for a Brighter Economic Future (National Academies Press, 2007).

Eom, J. et al. The impact of near-term climate policy choices on technology and emission transition pathways. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 90, 73–88 (2015).

Nemet, G. How Solar Energy Became Cheap: A Model for Low-Carbon Innovation (Routledge, 2019).

Victor, D. G., Geels, F. W. & Sharpe, S. Accelerating the Low Carbon Transition: The Case for Stronger, More Targeted and Coordinated International Action (Brookings Institution, 2019).

Andonova, L., Castro, P. & Chelminski, K. in Governing Climate Change (eds Jordan, A. et al.) Ch. 15 (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2018).

Lewis, J. I. Green Innovation in China: China’s Wind Power Industry and the Global Transition to a Low-Carbon Economy (Columbia Univ. Press, 2012).

Meckling, J. & Allan, B. B. The evolution of ideas in global climate policy. Nat. Clim. Change 10, 434–438 (2020).

Malhotra, A. & Schmidt, T. S. Accelerating low-carbon innovation. Joule 4, 2259–2267 (2020).

Larsen, K. et al. It’s Not Easy Being Green: Stimulus Spending in the World’s Major Economies (Rhodium Group, 2020).

Sabatier, P. A. & Weible, C. M. Theories of the Policy Process (Westview Press, 2014).

Keohane, R. O. & Victor, D. G. Cooperation and discord in global climate policy. Nat. Clim. Change 6, 570–575 (2016).

Zhang, F. et al. From fossil to low carbon: the evolution of global public energy innovation. WIREs Clim. Change https://doi.org/10.1002/wcc.734 (2021).

Anadón, L. D. Missions-oriented RD&D institutions in energy between 2000 and 2010: a comparative analysis of China, the United Kingdom, and the United States. Res. Policy 41, 1742–1756 (2012).

Meckling, J., Kelsey, N., Biber, E. & Zysman, J. Winning coalitions for climate policy: green industrial policy builds support for carbon regulation. Science 249, 1170–1171 (2015).

Chan, G., Goldstein, A. P., Bin-Nun, A., Anadon, L. D. & Narayanamurti, V. Six principles for energy innovation. Nature 552, 25–27 (2017).

Guellec, D. & van Pottelsberghe de la Potterie, B. The impact of public R&D expenditure on business R&D. Econ. Innovation New Technol. 12, 225–243 (2003).

Cohen, L. R. & Noll, R. G. The Technology Pork Barrel (Brookings Institution Press, 2002).

Wilson, C. et al. Granular technologies to accelerate decarbonization. Science 368, 36–39 (2020).

Breznitz, D., Ornston, D. & Samford, S. Mission critical: the ends, means, and design of innovation agencies. Ind. Corp. Change 27, 883–896 (2018).

OECD, World Bank & UN Environment Financing Climate Futures: Rethinking Infrastructure (OECD Publishing, 2018).

Narayanamurti, V. & Odumosu, T. Cycles of Invention and Discovery (Harvard Univ. Press, 2016).

Unruh, G. C. Understanding carbon lock-in. Energy Policy 28, 817–830 (2000).

Lundvall, B.-Å. National Systems of Innovation: Toward a Theory of Innovation and Interactive Learning, Vol. 2 (Anthem Press, 2010).

Nelson, R. R. National Innovation Systems: A Comparative Analysis (Oxford Univ. Press, 1993).

Hall, P. A. & Soskice, D. Varieties of Capitalism: The Institutional Foundations of Comparative Advantage (Oxford Univ. Press, 2001).

Garud, R. & Karnøe, P. Bricolage versus breakthrough: distributed and embedded agency in technology entrepreneurship. Res. Policy 32, 277–300 (2003).

Popp, D. Induced innovation and energy prices. Am. Econ. Rev. 92, 160–180 (2002).

Grubb, M. et al. Induced innovation in energy technologies and systems: a review of evidence and potential implications for CO2 mitigation. Environ. Res. Lett. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/abde07 (2021).

Probst, B., Touboul, S., Glachant, M. & Dechezleprêtre, A. Global trends in the invention and diffusion of climate change mitigation technologies. Nat. Energy 6, 1077–1086 (2021).

Commodity Price Data (World Bank, 2022); https://www.worldbank.org/en/research/commodity-markets

Bush, V. Science, the Endless Frontier (Ayer Company Publishers, 1995).

Gross, D. P. & Sampat, B. N. Inventing the Endless Frontier: The Effects of the World War II Research Effort on Post-War Innovation (National Bureau of Economic Research, 2020).

Myllyvirta, L. Sino–U.S. competition is good for climate change efforts. Foreign Policy https://foreignpolicy.com/2021/04/21/united-states-china-competition-climate-change/ (2021).

Erickson, A. S. & Collins, G. Competition with China can save the planet. Foreign Aff. 100, 136–149 (2021).

Bloom, N., Van Reenen, J. & Williams, H. A toolkit of policies to promote innovation. J. Econ. Perspect. 33, 163–184 (2019).

German Federal Government’s National Electromobility Development Plan (Bundesregierung, 2009); https://www.bmvi.de/blaetterkatalog/catalogs/219176/pdf/complete.pdf

Report from the Commission to the European Parliament and the Council: Progress on Competitiveness of Clean Energy Technologies (European Commission, 2021).

IPCC Special Report on Global Warming of 1.5 °C (eds Masson-Delmotte, V. et al.) (WMO, 2018).

Sivaram, V., Cunliff, C., Hart, D., Friedmann, J. & Sandalow, D. Energizing America (Columbia Univ. SIPA Center on Global Energy Policy, 2020).

Gates, B. How to Avoid a Climate Disaster (Random House, 2021).

Mazzucato, M. Mission Economy: A Moonshot Guide to Changing Capitalism (Harper Business, 2021).

Nahm, J. M., Miller, S. M. & Urpelainen, J. G20’s US$14-trillion economic stimulus reneges on emissions pledges. Nature 603, 28–31 (2022).

Atkinson, R. D. Why the United States Needs a National Advanced Industry and Technology Agency (Information Technology and Innovation Foundation, 2021).

Dutz, M. A., Yevgeny, K., Esperanza, L. & Dirk, P. Making Innovation Policy Work: Learning from Experimentation (OECD Publishing, 2014).

Sabel, C. F. & Victor, D. G. Making the Paris Process More Effective: A New Approach to Policy Coordination on Global Climate Change (The Stanley Foundation, 2016).

Hart, D. M. The Impact of China’s Production Surge on Innovation in the Global Solar Photovoltaics Industry (Information Technology and Innovation Foundation, 2020).

Carraro, C. Clubs, R&D, and climate finance: incentives for ambitious GHG emission reductions. FEEM Policy Brief No. 01 (Fondazione Eni Enrico Mattei, 2017).

Koester, S., Hart, D. M. & Sly, G. Unworkable Solution: Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanisms and Global Climate Innovation (Information Technology and Innovation Foundation, 2021).

Main Science and Technology Indicators Data (OECD, 2022); https://www.oecd.org/sti/msti.htm

Energy Technology RD&D Budgets. October 2021 Edition (International Energy Agency, 2021).

Dasgupta, S., De Cian, E. & Verdolini, E. in The Political Economy of Clean Energy Transitions, Vol. 123 (eds Arent, D. et al.) 123–143 (Oxford Univ. Press, 2016).

IPCC Climate Change 2022: Mitigation of Climate Change (eds Shukla, P. R. et al.) (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2022).

China Statistical Yearbook on Science and Technology (National Bureau of Statistics of China, 2020); http://www.stats.gov.cn/tjsj/tjcbw/202103/t20210329_1815746.html

Union Budgets, Expenditure Profile 2019–2020 (Ministry of Power, Government of India, 2019); https://www.indiabudget.gov.in/budget2019-20/doc/eb/stat1.pdf

Witt, M. A. et al. Mapping the business systems of 61 major economies: a taxonomy and implications for varieties of capitalism and business systems research. Socio-Econ. Rev. 16, 5–38 (2018).

Skovgaard, J., Ferrari, S. S. & Knaggård, Å. Mapping and clustering the adoption of carbon pricing policies: what polities price carbon and why? Clim. Policy 19, 1173–1185 (2019).

Tobin, P., Schmidt, N. M., Tosun, J. & Burns, C. Mapping states’ Paris climate pledges: analysing targets and groups at COP 21. Glob. Environ. Change 48, 11–21 (2018).

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge funding from the Hellman Fellows Fund; the Institute for Advanced Sustainability Studies; the US Department of Agriculture National Institute of Food and Agriculture, Hatch Project accession number 1020688; the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation, grant number 2019-9339, regranted through the California–China Climate Institute; the China Scholarship Council; and the EU Framework Programme for Research and Innovation H2020 under grant agreement number 730403 (INNOPATHS). We thank J. Guy and S. Vogel for comments on a draft manuscript. We thank N. Goedeking for research assistance, S. Kolesnikov for assistance in developing the methodology behind collecting public energy RD&D funding data for India and several colleagues for Korean language assistance. We are grateful to J. Sauer for assistance with the Freedom of Information requests for German public energy RD&D funding data.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.M. and L.D.A. conceived the study. J.M., C.G., E.S. and L.D.A. developed the methodology. C.G. and E.S. led data collection, with T.X. collecting data for China and J.M. and L.D.A. guiding data collection. C.G. and E.S. led data analysis, with J.M. and L.D.A. supporting analysis. J.M. wrote the manuscript, with C.G., E.S. and L.D.A. editing. J.M. administered the project.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Energy thanks David Hart, Eugenie Dugoua and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary information.

Supplementary Data 1

Funding data for China and India.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Meckling, J., Galeazzi, C., Shears, E. et al. Energy innovation funding and institutions in major economies. Nat Energy 7, 876–885 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41560-022-01117-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41560-022-01117-3

This article is cited by

-

The geoeconomic turn in decarbonization

Nature (2025)