Abstract

The increasing demand for high-energy Li-ion batteries for the electrification of personal transportation may lead to uncertainty in the global supply of raw materials (Co and Ni). Here we propose a novel Mn-rich composition, which has a quasi-ordered structure with previously unobserved two intermixed cation-ordering sequences. The partially ordered structure stabilizes the delithiated cathode at a high cut-off voltage, offering strain-free characteristics, with structural variations along both the a and c axes limited to approximately 1%. Consequently, the cathode can operate at 4.6 V while delivering a reversible capacity comparable to that of Ni-rich Li(Ni0.8Co0.1Mn0.1)O2. Moreover, a high capacity is maintained during long-term and high-voltage cycling in full cells with exceptional thermal safety. The high-performance Mn-rich layered cathodes characterized by quasi-ordered crystal structure can potentially relieve supply uncertainty resulting from the rising demand for Ni in the battery industry and environmental concerns associated with the extraction of Ni from its ores.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Global sales of electric vehicles (EVs) continue to increase, mainly driven by government subsidies, rising fossil fuel prices and the race to zero emissions1. Government mandates requiring that 50% of new vehicles be electric by 2030 in the United States, 100% by 2035 in the European Union and 40% by 2030 in China will inevitably place pressure on the raw material supply chain for Li-ion batteries (LIBs)2. According to the International Energy Agency, global demand for LIBs is projected to reach 3,500 GWh by 2030 (a tenfold increase from 2022)3. To alleviate future shortages and price increases of critical raw materials, LIB chemistry must be reengineered, especially that of the cathode, which is the most expensive and resource-intensive component4,5.

Supply uncertainty and price fluctuations of Co have inspired the development of Co-free layered cathodes6,7,8,9. The global reserves of Ni (95 million metric tons (ref. 10)) are much larger than those of Co (11 million metric tons (ref. 11)) and more evenly distributed geographically. The early adoption of LiCoO2 in LIBs has been replaced by Ni-rich compositions to increase the battery energy density. However, the use of Li[NixCoyMn1−x−y]O2 (NCM) and Li[NixCoyAl1−x−y]O2 (NCA) layered cathodes with Ni contents of >80% is predicted to increase the demand for Ni from the battery industry from 7% in 2021 to 41% by 2040 (ref. 12). In addition, Ni mining practices cause environmental problems, including groundwater contamination resulting from the storage and deep-sea disposal of tailings13. Hence, in addition to eliminating Co from the cathode, the Ni content should be reduced. Co-free layered oxide cathode containing multiple metal elements, Li[Ni0.8Mn0.13Ti0.02Mg0.02Nb0.01Mo0.02]O2, was recently proposed14,15. However, the synthesis and production of compositionally complex cathodes remains a challenge. The sustainable production of layered cathodes for LIBs requires a major paradigm shift in cathode chemistry16. Compared with Ni, Mn is cheaper, less toxic and environmentally benign; thus, Mn-rich layered cathodes are a logical alternative to Ni-rich layered cathodes17,18. Despite its potential as a cathode for LIBs, LiMnO2 cannot be used owing to synthesis difficulties caused by thermodynamic instability, the Jahn–Teller distortion of Mn3+ ions and Mn dissolution19,20.

In this study, we investigated Mn-rich layered cathodes synthesized using a conventional co-precipitation method. In the proposed Mn-rich layered cathodes, Mn exists primarily as Mn4+, thereby avoiding lattice-destabilizing Jahn–Teller distortion, and forms a network of quasi-ordered nanoscale domains, in which Li+ and transition metal (TM) ions alternate in a 1:2 ratio (LTTLTT or TLLTLL, where L is Li excess and T is TM excess). Notably, the proposed Mn-rich layered cathodes exhibit strain-free properties, outstanding thermal safety and long-term cycling stability at high cut-off voltages and elevated temperatures.

Quasi-ordered crystal structure

The chemical compositions of the conventional and quasi-ordered Mn-rich NCM cathodes (denoted as NCMx and QO-NCMx, wherein x corresponds to Ni ratio) are listed in Supplementary Table 1. The preparation of layered NCM cathodes with Mn fractions greater than 30% via co-precipitation is not trivial. Dense and spherical QO-NCM45 precursor particles with radially oriented rod-like primary particles were synthesized by carefully controlling the pH to 10.2 at 30 °C during co-precipitation (Supplementary Figs. 1a,b). The shell region of the QO-NCM45 cathode particles is tightly packed with primary particles that are elongated and radially aligned (Supplementary Figs. 1c–f). In comparison, the commercial NCM50 is comprised of relatively thick and equiaxed grains that are irregularly oriented. The X-ray diffraction (XRD) data reveal that the QO-NCM45 cathode has a layered structure in the \(R{\bar{3}}m\) space group and no impurity peaks related to Li2MnO3 (Supplementary Fig. 2). Similarly, other Mn-rich QO-NCM and QO-NM cathodes are free of Li2MnO3. The calculated lattice parameters indicate that QO-NCM45 has a slightly larger unit cell volume with considerably higher Li+/Ni2+ cation mixing than NCM50 (Supplementary Table 2). The X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) spectra and X-ray absorption near-edge structure (XANES) results indicate that substantial fractions of both Ni2+ and Mn4+ are required to maintain charge neutrality (Supplementary Figs. 3 and 4). The formation of Mn4+ (0.54 Å) in QO-NCM45 produced Ni2+ (0.69 Å) to maintain charge neutrality, thereby increasing the overall change in ionic radius and the degree of Li+/Ni2+ mixing21,22,23,24.

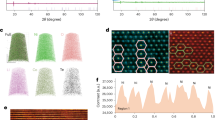

The selected area electron diffraction (SAED) pattern of a QO-NCM45 primary particle along the [100] zone is identical to that of a layered structure (Fig. 1a). However, upon rotating this crystal 30° along the layered plane, the [\(1\bar{1}0\)] pattern exhibits additional peaks and streaks parallel to the [001] direction that are absent from the calculated [\(1\bar{1}0\)] diffraction pattern (Figs. 1b,c). The extra peaks (yellow circles, Fig. 1b) are equally spaced at one-third the distance of the (\(1\bar{1}0\)) diffraction spot. The [\(1\bar{1}0\)] zone is nearly identical to the [010]mono zone of Li2MnO3 with stacking faults25. When the Mn layer of Li2MnO3 is projected along the [100]hex//[100]mono direction, each atomic column contains 2/3Mn, such that the Li2MnO3 and LiTMO2 structures are indistinguishable (Fig. 1d). However, when projected along the [\(1\bar{1}0\)]hex//[010]mono direction, superlattice formation by the repeating Li–Mn–Mn sequence can be distinguished. Comparison with Li2MnO3 suggests that the presence of Li2MnO3 pockets can explain the SAED patterns of QO-NCM45. However, a high-resolution [\(1\bar{1}0\)] zone transmission electron microscopy (TEM) image of QO-NCM45 does not support this assignment. Equally spaced streaks remain after Fourier transform of the imaged region (20 nm × 20 nm), indicating that the SAED pattern does not originate from a two-phase mixture but from atomic ordering (Fig. 1e). Note that the SAED aperture covers an area as large as 125 nm in diameter, indicating that the ordered crystal structure is not a localized phenomenon but extends several hundreds of nanometres. In addition, identical SAED patterns were observed in many primary particles, suggesting that the quasi-ordered structure is prevalent and occurs on a microscopic scale (Supplementary Fig. 5a). The magnified image and line scan along an atomic column in region A show contrast consistent with a series of triplets (…TLL–TLL–TLL…) and the distance between two atomic columns (0.14 nm) corresponds to the interplanar distance of the (\(1\bar{1}0\)) plane (Fig. 1f). An atomic column in region B, which is adjacent to region A, exhibits reverse contrast corresponding to …LTT–LTT–LTT… triplets. The TEM contrast in the Li layer suggests the formation of a similar quasi-ordered structure by Ni2+ ions that migrated to the Li layer. The atomic layers are well aligned without any stacking faults, indicating that the streaks of SAED originate from the LTT and TLL triplets. Thus, the QO-NCM45 cathode has an ordered nanoscale structure in which the TM layer is composed of repeating LTT and TLL triplets. A decrease in the Mn–Me and Ni–Me coordination intensity from extended X-ray absorption fine structure (EXAFS) in QO-NCM45 provides further evidence for the presence of a quasi-ordered structure in QO-NCM45 (Supplementary Figs. 6a,b). The structure diagram of the QO-NCM45 viewed along the different directions is shown in Supplementary Fig. 5b. Because the Li–Mn–Mn atomic arrangements in QO-NCM45 are discontinuous, the structure is different from that of the Li2MnO3 nanodomain with a continuously repeating Li2MnO3 unit cell. The TEM, soft X-ray absorption spectroscopy (sXAS), Raman and XRD analyses complement each other by providing information from the surface to the bulk of the material, demonstrating that Li2MnO3 does not exist in QO-NCM45 (Supplementary Figs. 6c–e). The quasi-ordered structure is completely different from the long-range cation ordering in Li[Ni0.5Mn0.5]O2, which involves the formation of a \(\sqrt{3}\)ahex × \(\sqrt{3}\)ahex× chex superlattice26. Such a quasi-ordered structure has not been reported previously, which renders QO-NCM and Co-free QO-NM cathodes a new breed of layered oxide cathode. The formation of quasi-ordered structures apparently occurs in a narrow range of Mn fractions, as the partial ordering disappears when the Mn fraction reaches 30% in NCM50 (Supplementary Fig. 7). The keys to developing the quasi-ordered crystal structure in the Mn-rich cathodes are their unique precursor microstructure featuring rod-like primary particles and the high Mn-to-Co ratio. To the best of our knowledge, no previous studies have designed or reported rod-shaped primary particles in Mn-rich hydroxide precursors and cathode materials. During calcination, the aligned fine primary particles composed of stacked TM layers aggregate and this leads to the ordered intermixing of cations, forming quasi-ordered crystal structure in the final product. However, if the primary particles are randomly oriented, the aggregation of TM layer stacks with different orientations results in thick and bulky primary particles with randomly intermixed cations. Because the activation energy for interdiffusion of Mn is substantially lower than that of Co, the cathodes with high Mn-to-Co ratios are invulnerable to the high temperature sintering, maintaining the aligned rod-like primary particles, forming a quasi-ordered crystal structure27.

a,b, [100] (a) and [\(1\bar{1}0\)] (b) zone SAED patterns of QO-NCM45. Additional electron diffraction spots distinct from those originating from the normal layered structure are marked in yellow. c, Simulated [\(1\bar{1}0\)] zone electron diffraction pattern of a layered \(R\bar{3}m\) structure. d, Schematic illustration of the atomic arrangement in Li2MnO3 viewed along the [100] and [\(1\bar{1}0\)] directions. e, Fourier transform (FT) of a 20 nm × 20 nm region of QO-NCM45. f, High-angle annular dark-field TEM images and contrast line scans along atomic columns from regions A and B of QO-NCM45. g, [100] (left) and [\(1\bar{1}0\)] (right) zone SAED patterns of QO-NCM45 after charging to 4.4 V. Additional electron diffraction spots distinct from those originating from the normal layered \(R\bar{3}m\) structure are marked with blue arrows and green circles. h, Schematic illustrations of the atomic arrangements of layered, spinel and cation-ordered structures. i, [100] (left) and [\(1\bar{1}0\)] (right) zone SAED patterns of QO-NCM45 after charging to 4.6 V. j,k, [\(1\bar{1}0\)] zone SAED patterns of QO-NCM45 after discharging to 2.7 V (j) and 100 cycles (k). SAEDs are obtained with an aperture size of 125 nm in diameter.

The structural changes of QO-NCM45 during charge closely follow those of Li2MnO3 than to those of Li[Ni0.5Mn0.5]O2 (ref. 28). Upon charging to 4.4 V (71% Li extracted), the [100] zone SAED pattern shows that the layered structure transforms into a cation-ordered structure with an extra series of superlattice peaks, as previously observed for Zr-doped LiNiO2 (ref. 29). Furthermore, the [\(1\bar{1}0\)] zone SAED pattern contains spots corresponding to the [211] zone of a disordered spinel structure in addition to the faint streaks observed in the uncharged state (Fig. 1g). A high-resolution TEM image of the spinel region shows that the atomic ordering changes to LT–LT–LT… doublets with an atomic spacing of 0.14 nm as Ni ions migrate into the Li layer (Supplementary Fig. 8a). Figure 1h illustrates the atomic arrangements of the layered, spinel and cation-ordered structures observed in charged QO-NCM45. When further charged to 4.6 V (90% Li extracted), the extra spots in both the [100] and [\(1\bar{1}0\)] zones became fainter owing to transformation into a spinel structure (Fig. 1i). However, unlike Li2MnO3, in which the phase transitions during the first charge are irreversible (ref. 30), the partially ordered structure of QO-NCM45 can be regenerated as Ni ions reversibly migrate back to the TM layer. The SAEDs of QO-NCM45 obtained at various state of charge and depth of discharge demonstrate the reversible phase transition of QO-NCM45 (Fig. 1j and Supplementary Figs. 8b,c). Such reversible migration of Ni between the Li and TM layers has been observed in Li[Ni0.5Mn0.5]O2 (ref. 31). The presence of LTT and TLL triplets in QO-NCM45 after cycles at 4.6 V demonstrates the excellent structural durability of the quasi-ordered structure and distinguishes the structure from the Li-rich cathodes featuring Li2MnO3 (Fig. 1k and Supplementary Figs. 8d–h).

Strain-free properties

The partial ordering of the QO-NCM cathodes helps stabilize the delithiated structure. The charging curves during the in situ XRD analyses and the corresponding diffraction peaks are shown in Supplementary Fig. 9. Similar to other layered cathodes, the c-axis lattice parameter of the QO-NCM45 cathode initially expands (Δc/c0 = +1.3% at ~4.23 V), whereas the a-axis lattice parameter decreases continuously (Supplementary Fig. 10). At 4.23 V, the c-axis lattice begins to contract, reaching Δc/cmax of −0.6% at 4.5 V and −0.9% at 4.6 V. In the fully charged state at 4.6 V, the change in the c-axis lattice parameter (Δc/c0) is nearly zero (0.36%) (Fig. 2a). In addition, the QO-NCM50 and Co-free QO-NM60 show similar extent of lattice parameter variation. The appearance of a single (003) XRD reflection peak in QO-NCM45 (Supplementary Fig. 9), as opposed to the splitting of peaks typically observed in structurally heterogeneous, single-crystalline NCM cathodes, indicates the absence of structural heterogeneity32. In addition, the ex situ TEM results of QO-NCM45 further support that the structural evolution is homogeneous within the cathode particle (Supplementary Figs. 11–13). Thus, Mn-rich QO-NCM and QO-NM cathodes are ‘strain-free’ cathodes. The observed strain-free feature during delithiation not only minimizes the mechanical stress on the cathode during charging but is also important in solid-state batteries in which the lattice contraction of Ni-rich layered cathodes often causes contact loss with the solid electrolyte33,34. In comparison, NCM50, NCM60, NCM80, NCM90 and LNO cathodes exhibited maximum contraction of the c axis during charging at 4.6 V (Δc/cmax = −3.3%, −3.7%, −4.4%, −6.6% and –8.0%, respectively; Supplementary Table 3). Lattice contraction adversely affects the mechanical stability of layered cathodes, largely because of its abruptness and anisotropy35,36,37,38. The anisotropy ratio ((∆a/a0)/(∆c/c0)) was determined to estimate the extent of abrupt anisotropic straining of the lattice during delithiation (Fig. 2b). The anisotropy ratio of ultra-Ni-rich LNO sharply decreases and then suddenly increases near 4.2 V, which coincides with the detrimental H2 → H3 phase transition38. The change in anisotropy ratio broadens with decreasing Ni content, as the H2 → H3 phase transition is delayed at low Ni contents. In comparison, the anisotropy ratio of QO-NCM45, QO-NCM50 and Co-free QO-NM60 remains nearly constant up to 4.5 V and only begins to tail off at 4.6 V, confirming the strain-free extraction of Li+ from the lattice. By constructing quasi-ordered crystal structures, the anisotropicity of lattice variation during electrochemical (de)lithiation is exceedingly suppressed. Previous reports have shown novel crystal structures with structural stabilization effects36,39,40,41. For example, Lu presented a strain-retardant coherent perovskite phase via La doping in NCM80 (ref. 36). Tarascon demonstrated a composite of LiNiO2-rich and LixMyOz-rich, where M = W and Mo, phases in Li1+yNi(3-5y)/3M2y/3O2 cathode with epitaxial stabilization effects40,41. Compared to the previous reports, the proposed quasi-ordered structure can be observed in several QO-NCM and Co-free NM compositions without additional doping.

High-voltage cycling performances

The first charge–discharge curves of the QO-NCM45 and Li-rich Li[Li0.13Ni0.30Mn0.57]O2 cathodes differ significantly. During the first charge, Li[Li0.13Ni0.30Mn0.57]O2 exhibits an extended plateau at 4.5 V with a Coulombic efficiency of only ~83% (Fig. 3a). In contrast, QO-NCM45 exhibits a barely discernible shoulder at 4.48 V with a Coulombic efficiency of 93% while producing a discharge capacity of 224.7 mAh g−1 at 0.1 C. The differential capacity curve of QO-NCM45 calculated from the first charge–discharge curves (cycled from 3.0 V to 4.8 V at 0.1 C) shows a broad oxidation peak during the first charge, unlike the sharp, nearly discontinuous peak observed for Li[Li0.13Ni0.30Mn0.57]O2 (Fig. 3b) (refs. 42,43). The different charge profiles of QO-NCM45 are indicative of the different structural features and, hence, different structural formation mechanisms of QO-NCM45. Notably, the QO-NCM45 cathode achieves outstanding cycling stability and energy efficiency at high potentials and elevated temperatures (Supplementary Fig. 14). The cathode delivers discharge capacities of 205.9 mAh g−1 at 1 C, while maintaining 97.4% of the initial capacity after 100 cycles at 4.6 V and 45 °C (Fig. 3c). Commercial NCM50 and Li[Li0.13Ni0.30Mn0.57]O2 retain only 86.4% and 87.9% of their initial capacities, respectively, after 100 cycles (Fig. 3c). On the basis of the sXAS results, the charge compensation mechanism of the QO-NCM45 is different from that of the Li[Li0.13Ni0.30Mn0.57]O2 but similar to that of the layered NCM50 (Supplementary Figs. 15a–c). Li[Li0.13Ni0.30Mn0.57]O2 undergoes oxygen anionic redox at approximately 4.5 V, but that of QO-NCM45 and NCM50 is at 4.7 V. Additionally, the reversible changes observed in the Ni K-edge XANES spectra of QO-NCM45 during cycling suggest that the cation redox is highly reversible (Supplementary Figs. 15d–o). This demonstrates that unlike Li-rich cathodes that deliver high capacity through anionic redox, QO-NCM45 operates through cation redox. The Mn-rich QO-NCM and Co-free QO-NM cathodes with different chemical compositions also exhibit excellent cycling stability at 4.6 V, delivering capacity retention of 97.4%, 96.1% and 95.2% after 100 cycles for the QO-NCM40, QO-NCM50 and Co-free QO-NM60, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 16a–c). In addition, the excellent cycling performance of the QO-NCM cathodes is not limited to the specific electrolyte composition or the fluoroethylene carbonate (FEC) amounts (Supplementary Figs. 16d,e). Though the low-temperature performance of the QO-NCM45 is relatively inferior to that of the NCM50 due to the lower Co content (Supplementary Figs. 17c,d), we believe that several engineering approaches, such as particle size modification and carbon coating or electrolyte modification, that have improved the low-temperature performance of LiFePO4 can be similarly applied to further improve the low-temperature performance of QO-NCM45.

a,b, Initial charge–discharge curves (a) and differential capacity profiles (b) of NCM50, QO-NCM45 and Li[Li0.13Ni0.30Mn0.57]O2. c, Electrochemical cycling performance of NCM50, QO-NCM45 and Li[Li0.13Ni0.30Mn0.57]O2 at 3.0–4.6 V (versus Li/Li+) and 45 °C. d, Electrochemical performance comparison of QO-NCM45 and conventional Li[NixCoyMn1−x−y]O2 (x = 0.5, 0.6, 0.8 and 0.9) cathodes. Grey grid line indicates capacity retention of 95% after 100 cycles. e, Long-term cycling performance of pouch-type full cells featuring graphite anodes and conventional NCM50 or QO-NCM45 or QO-NCM50 or Co-free QO-NM60 cathodes in the voltage range of 3.0–4.4 V (versus graphite). For comparison, data are also shown for full cells with conventional NCM cathodes (NCM60, NCM80 and NCM90) cycled in the voltage range of 3.0–4.2 V (versus graphite).

Ni-rich NCM90, NCM80 and NCM60 were tested at various cut-off potentials, but their cycling performance remained inferior to that of QO-NCM45 at 4.6 V (Supplementary Figs. 18a–c). Extraction of large amounts of Li+ from the host structure typically leads to structural collapse, which compromises the electrochemical performance in Ni-rich cathodes. However, the strain-free nature of QO-NCM45 enables stable cycling at high voltages. Despite the cycling stabilities of QO-NCM45 at 3.0–4.6 V and commercial LiFePO4 at 2.5–3.9 V being similar, QO-NCM45 provides a 40–65% higher energy density (Supplementary Fig. 18d,e). Therefore, the QO-NCM45 cathode represents a new breed of layered cathode that can deliver a higher energy density (879 Wh \({{\rm{kg}}}_{{\rm{cathode}}}^{\!-1}\)) than NCM80 at 4.6 V with improved capacity retention (Fig. 3d). In addition, the QO-NCM45 cathode contains 35% less Ni than NCM80, which reduces the material cost and supply risk owing to the abundance of natural Mn sources.

To demonstrate the feasibility of the proposed Mn-rich QO-NCM45 cathode for practical applications, a full cell was constructed with a graphite anode. The long-term cycling data at 1 C and 45 °C show that this cathode retains 85.5% of the initial capacity after 1,000 cycles in the voltage range of 3.0–4.4 V (versus graphite) (Fig. 3e). This cycling performance, which meets the guaranteed battery life threshold of EV manufacturers ( ~ 80% of the initial capacity at the end of service life), is equivalent to a battery life of approximately 20 years for an EV subjected to full charging weekly. The outstanding cycling performance of the quasi-ordered structure is also demonstrated in a full cell with Mn-rich QO-NCM50 and Co-free QO-NM60 cathode which retains 81.8% and 88.2% of their initial capacity after 1,000 and 500 cycles, respectively. Under the same cycling conditions, commercial NCM50 retains only 46.7% of its initial capacity. Impressively, during long-term cycling, the full cells with QO-NCM and QO-NM cathodes outperform those with Ni-rich cathodes (NCM60, NCM80 and NCM90) cycled at 3.0–4.2 V, which is the typical cycling condition for LIBs (Fig. 3e and Supplementary Fig. 18f). The Mn-rich QO-NCM45 is a state-of-the-art cathode that surpasses previously reported layered NCM cathodes in terms of specific capacity and cycling stability at high voltages (Supplementary Fig. 19 and Supplementary Tables 4 and 5). In addition, unlike the Li[Li0.13Ni0.30Mn0.57]O2 cathodes44,45,46,47, QO-NCM45 shows a stable nominal voltage during long-term cycling (Supplementary Figs. 20a–c). Increasing the cut-off voltage to 4.5 V (versus graphite) further validated the long-term cycling stability of QO-NCM45; however, extended cycling at 4.5 V was hindered by the instability of the ethylene carbonate-based electrolyte48 (Supplementary Figs. 20d,e).

Li+/Ni2+ cation mixing is believed to hinder Li+ migration and thus deteriorate the rate capability of Ni-rich layered cathodes49. To investigate the Li+ migration energy barrier of QO-NCM45, the Nudged Elastic Band (NEB) method with density functional theory (DFT) calculation was used. The NEB results reveal that the quasi-ordered structure has Li+ migration energy barrier of approximately 1.33 eV (Supplementary Fig. 21). This value is higher than the energy barriers calculated for the O3-layered ( ~ 0.65 eV) and spinel ( ~ 0.22 eV) phases. The presence of TM cations within the Li layers in the quasi-ordered structure retards Li+ migration, resulting in a higher Li+ migration energy barrier compared to the O3-layered structure. Note that the Li-rich cathode exhibited a significant change in energy efficiency when evaluated under different overpotential conditions (0.1 C at 45 °C and 0.02 C at 60 °C), whereas QO-NCM45 showed only minimal variation (Supplementary Fig. 22). This suggests that the low energy efficiency of Li-rich cathodes is primarily due to a substantial increase in overpotential caused by the presence of Li2MnO3 and the subsequent O redox reaction. In contrast, QO-NCM45 is relatively unaffected by overpotential. Therefore, the slightly lower energy efficiency of QO-NCM45 compared to layered NCM50 is probably attributed to a higher Li+ migration energy barrier caused by the formation of LTT and TLL atomic arrangements. Among the cathodes, Li-rich Li[Li0.13Ni0.30Mn0.57]O2 showed the worst rate performance (Supplementary Fig. 14f). Whereas the rate performance of QO-NCM45 is inferior to that of NCM50, the reduction is less severe relative to the magnitude of the increase in the Li+ migration energy barrier. This can be attributed to the development of a spinel structure in QO-NCM45 at the highly delithiated state (4.4–4.6 V), which facilitates Li+ migration.

Post-mortem analyses

The strain-free feature, resulting from the partially ordered structure, allows the QO-NCM45 cathode to avoid mechanical damage during cycling (Supplementary Figs. 23a,b). In general, the intensity of the XRD peak during the cycling of NCM cathodes decreases as cycling progresses due to the accumulation of irreversible damage to the cathode50. The operando XRD pattern after long-term and high-voltage cycling of the full cell demonstrates the electrochemical reversibility of QO-NCM45, whereas a discontinuous and significantly decayed phase transition peak is observed for the NCM50 cathode (Figs. 4a,b). The cross-sectional scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images of the cycled QO-NCM45 cathode confirm that the cathode particles remain mechanically intact and maintain their initial spherical shape after cycling (Figs. 4c,d and Supplementary Figs. 23c–f). Despite cycling at 4.4 V (versus graphite) for long-term cycles, QO-NCM45 remains nearly free of microcracks, which is remarkable considering that layered cathodes tend to deteriorate faster at elevated voltages and temperatures51,52. In comparison, the cycled NCM50 cathode particles exhibit near pulverization. The 7Li distribution within the charged cathode particles (4.4 V versus graphite) was mapped using 7Li time-of-flight secondary ion mass spectrometry (ToF-SIMS) (the 55Mn maps are shown as a reference in Supplementary Figs. 23g–j). Despite being fully charged, NCM50 still contains many grains with high 7Li concentrations. The coexistence of Li-poor and Li-rich regions, an indication of electrochemically dead regions53, accounts for the capacity loss of NCM50 (Fig. 4e). However, the relatively homogeneous and low concentration of 7Li in cycled QO-NCM45 indicate that the high structural durability and unique microstructure of this cathode contribute to spatially uniform delithiation (Fig. 4f).

a,b, Operando XRD contour plots in the 2θ range corresponding to the (003) reflection for full cells with NCM50 (a) and QO-NCM45 (b) cathodes after 750 cycles in the voltage range of 3.0–4.4 V (versus graphite). c,d, Greyscale inverted cross-sectional SEM images of NCM50 (c) and QO-NCM45 (d) after 1,500 cycles in full cells cycled in the voltage range of 3.0–4.4 V (versus graphite). e,f, ToF-SIMS cross-sectional 7Li maps of NCM50 (e) and QO-NCM45 (f) cathodes charged to 4.4 V (versus graphite) after recovery from full cells after 1,500 cycles in the voltage range of 3.0–4.4 V (versus graphite).

Thermal safety and chemical stability

A Mn-rich surface can improve the thermal stability of layered cathodes. Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) measurements indicate that the thermal stability of the QO-NCM45 cathode is significantly enhanced compared with that of the commercial layered cathodes (NCM50, NCM80 and NCM90) (Fig. 5a). The charged commercial cathodes undergo violent exothermic reaction around 180–240 °C, releasing copious amount of heat (3,192; 2,431; 1,893 and 2,011 J g−1 for NCM90 charged to 4.3 V, NCM80 charged to 4.3 V, NCM50 charged to 4.5 V and NCM50 charged to 4.6 V, respectively). The observed sharp rise in temperature leads to rapid thermal propagation which is difficult to suppress by the thermal management system54,55,56,57. In comparison, the onset of the exothermic reaction for the QO-NCM45 cathode charged to 4.6 V is delayed by 15.9 °C; moreover, the released heat is only a fraction (35%) of that for the NCM50 cathode. The relatively low, broad exothermic peak effectively eliminates the danger of the rapid thermal propagation. The accelerating rate calorimetry (ARC) experiment was also conducted. In ARC results, T1, T2 and T3 indicate the onset temperature of a battery self-heating, the starting temperature of uncontrollable thermal runaway and the maximum cell temperature during thermal runaway reactions, respectively. As shown in Fig. 5b, the tested full cells show nearly identical heat–wait–seek profiles, indicating that the adiabatic condition was well maintained during the ARC experiment (Supplementary Fig. 24). The use of quasi-ordered cathodes featuring high Mn contents ( ≥ 40%) helped to alleviate the self-heating of batteries; the T1 for NCM90, NCM50, QO-NM60 and QO-NCM45 is 119.4, 125.7, 139.6 and 147.4 °C, respectively. In addition, the onset of thermal runaway reaction in a full cell featuring QO-NCM45 is delayed by more than 25 °C than that of a full cell featuring NCM50; the T2 for NCM90, NCM50, QO-NM60 and QO-NCM45 is 199.5, 204.1, 213.3 and 234.6 °C, respectively. The delay of T2 indicates the high structural stability of the quasi-ordered crystal structure, as the heat generation by oxygen release from cathode material is the major heat source at this stage. Differential temperature profiles versus the temperature of the pouch cells clearly demonstrate that the rate of temperature rise is markedly alleviated in full cells featuring Mn-rich quasi-ordered cathodes (Fig. 5c). The T3 for NCM90, NCM50, QO-NM60 and QO-NCM45 is 313.8, 433.9, 279.7 and 301.9 °C, respectively. Furthermore, because the Mn-rich surface of QO-NCM45 is relatively inert and contains negligible amounts of residual lithium (2,900 ppm), oxidative decomposition of the electrolyte and gas evolution can be alleviated (Fig. 5d and Supplementary Fig. 25). After 45 d of storage-swelling experiments, the pouch seals released gas in the following amounts: NCM90 (1.62 ml gA.M.−1 at 4.3 V), NCM80 (1.18 ml gA.M.−1 at 4.3 V), NCM50 (1.43 ml gA.M.−1 at 4.5 V) and QO-NCM45 (0.93 ml gA.M.−1 at 4.5 V), demonstrating significantly reduced gas evolution in the QO-NCM45. Because the pouch seals for storage-swelling experiment do not contain a separator or anode, the evolved gas can be directly related to the stability of cathode materials. In addition, because of the negligible amount of residual lithium, the QO-NCM45 cathode does not require a washing process, which will further reduce manufacturing costs. Owing to the chemically stable Mn-rich surface of QO-NCM45, TM dissolution is significantly decreased during storage in a highly delithiated state in the electrolyte solution, suggesting that this cathode can also aid in maintaining the structural durability of the graphite anode (Supplementary Fig. 26). The large surface area of QO-NCM45 resulted in a relatively thicker cathode–electrolyte interphase than that of NCM50 during short-term cycles (Supplementary Fig. 27a,b). However, due to the high concentration of Mn4+ on the QO-NCM45 surface, the cathode–electrolyte decomposition reactions are largely alleviated during long-term and high-voltage cycling (Supplementary Fig. 27c). The sustainable development of cathode materials should take into account both the raw elements that make up the materials and the recycling aspects after their use. Conventionally, the recycling yield target for Mn is not as high as for expensive elements (Li, Ni and Co) due to the low material price and abundant resources58,59. If Mn recycling technology is further developed together with the use of Mn-rich cathodes, a more sustainable battery circulation cycle will be possible.

a, DSC profiles of delithiated QO-NCM45, Co-free QO-NM60 and conventional Li[NixCoyMn1−x−y]O2 (x = 0.5, 0.8 and 0.9) cathodes. b,c, ARC results of charged pouch-type full cells featuring NCM90, NCM50, QO-NM60 and QO-NCM45: cell temperature and voltage profiles versus real time (b) and differential temperature profiles versus cell temperature (c). d, Amounts of gas evolved during storage of pouch seals with delithiated cathodes and electrolyte solution at 60 °C. For the storage-swelling experiments, NCM50 and QO-NCM45 were charged to 4.5 V (versus Li/Li+) and NCM80 and NCM90 were charged to 4.3 V (versus Li/Li+).

Conclusions

QO-NCM45 represents a new type of Mn-rich layered NCM cathode with a quasi-ordered crystal structure and two different cation-ordering sequences. This quasi-ordered structure minimizes the lattice strain in the charged state and stabilizes the delithiated structure at high cut-off voltages. The strain-free properties of QO-NCM45 allows this cathode to be cycled up to 4.6 V and deliver a reversible capacity comparable to that of NCM80. Because Mn is lighter than Ni, the high capacity and operating voltage of QO-NCM45 increase the power and energy densities of LIBs. The QO-NCM45 cathode can maintain its capacity during long-term cycling at 4.4 V (versus graphite) and 45 °C and shows exceptional thermal safety, which demonstrates its feasibility for practical applications. In addition to these enhanced performance characteristics, the Mn-rich nature of the QO-NCM45 layered cathode can relieve the supply uncertainty arising from the growing demand for Ni in the battery industry and environmental concerns associated with the extraction of Ni from its ores. The Mn-rich QO-NCM and QO-NM cathodes represent a step towards the sustainable production and use of safe LIBs.

Methods

Synthesis of QO-NCM and QO-NM cathode materials

The Mn-rich [NixCo1−x−yMny](OH)2 (cathode active material precursor) was synthesized via a co-precipitation reaction in a batch-type reactor (17 l). First, a 2 M aqueous metal solution was prepared using NiSO4·6H2O (Samchun Chemical, 98.5%), CoSO4·7H2O (Daejung Chemical, 98%) and MnSO4·H2O (Daejung Chemical, 98%) at a Ni:Co:Mn molar ratio of x:1−x−y:y. The aqueous metal solution, 4.0 M aqueous NaOH (Samchun Chemicals) and 10.5 M aqueous NH4OH (Junsei Chemical) were continuously fed into a reactor containing NaOH, NH4OH and deionized water. The pH range for co-precipitation was optimized according to the transition metal ratios. During the synthesis of [Ni0.45Co0.1Mn0.45](OH)2, [Ni0.4Co0.1Mn0.5](OH)2, [Ni0.5Co0.1Mn0.4](OH)2 and [Ni0.6Mn0.4](OH)2, the pH was kept at 10.2, 10.0, 10.4 and 10.5 at 30 °C, respectively. The reactor was continuously purged with N2(g) during the synthesis process. After synthesis, the precipitates were washed with deionized water to remove NH3-, \({\rm{SO}}\)42−- and Na-associated residues. To ensure complete dehydration, the washed precursors were filtered and subsequently dried in a vacuum oven at 110 °C for 10 h.

To prepare the Mn-rich cathode active materials, Mn-rich [NixCo1−x−yMny](OH)2 and Li2CO3 (Junsei Chemical) were homogeneously mixed at a Li:(Ni+Co+Mn) molar ratio of 1.01:1. To prepare the Li-rich cathode active materials, [Ni0.35Mn0.65](OH)2 and Li2CO3 were homogeneously mixed at a Li:(Ni+Mn) molar ratio of 1.32:1. The mixed materials were calcined at 920 °C for 10 h in a tube furnace (Lindberg, Thermo Fisher) under an O2 atmosphere. The heating and cooling rates were 2 °C min−1. Commercial NCM50 (Umicore), NCM60 (EcoPro BM), NCM80 (Umicore), LiFePO4 (MTI) and conventional NCM90 cathode active materials were used for comparison.

Analytical approach

To determine the chemical compositions of the cathode materials, inductively coupled plasma-atomic emission spectrometry (iCAP 7400DUO, Thermo Fisher Scientific) was utilized. The particle morphology was characterized via SEM (Verios G4 UC, FEI). The samples for cross-sectional analysis were prepared by cutting the electrode using a cross-sectional polisher (IB-19520CCP, JEOL). The average length, width and orientation angle of the primary particles were determined using image processing software (ImageJ). To investigate the crystal structures of the cathode materials, XRD measurements (Empyrean, PANalytical) were carried out using Cu Kα radiation source. XRD data were obtained in the 2θ range of 10–130° with a step size of 0.0131°. For operando XRD analysis, a pouch-type half-cell was charged at a constant C-rate of 0.05 C (9 mA g−1) and measurements were recorded every 40 min in transmission mode using an X-ray detector (PIXcel 1D, PANalytical). To investigate the structural deterioration of the cathodes after electrochemical cycling, operando XRD measurements of the cycled full cells were performed during electrochemical charging at a constant C-rate of 0.05 C. The obtained XRD patterns were analysed using a Rietveld refinement programme (FullProf). XPS measurements (K-alpha+, Thermo Scientific) were performed using a monochromatic Al Kα source at an X-ray power of 12 keV and 6 mA. For an investigation of the oxidation states of the cathode constituents, the cross-section of the cathode materials was used as a specimen. XPS depth profiling was conducted for 100 s with an Ar+ sputter gun at an X-ray power of 1 keV. TEM (JEM ARM200F, JEOL) was used to characterize the crystal structures of the cathode materials. X-ray absorption spectroscopy (XAS) analysis of the Ni and Mn K-edge was performed at the 10 C beamline of the Pohang Accelerator Laboratory (PAL). The measurement of X-ray absorption near-edge structure (XANES) and extended X-ray absorption fine structure (EXAFS) spectra were gained in transmission mode at room temperature. The electrode was covered with tightly adhered Kapton film and exposed to incident synchrotron X-rays. The film was firmly applied to minimize O2 bubble formation, thereby minimizing the interference in the XANES/EXAFS signal. For data interpretation, the XAS data were processed using the Athena software. sXAS was performed at the 10D HR-PESI beamline of PAL. The electrodes used for analysis were fabricated with a weight ratio of active material:conducting agent:PVDF = 96:2:2. Raman spectroscopy was conducted using a DXR2xi (Thermo Fisher Scientific) equipped with a 532 nm laser and a beam diameter of approximately 2 μm. The spectra were recorded over the range of 50 to 3,500 cm−1. The TEM samples were prepared by cutting the cathode materials into thin foils using a focused ion beam (FIB; Helios, FEI). To map the spatial distribution of 7Li, cathode cross-sections were analysed using a plasma focused ion beam (PFIB; Helios PFIB G4 CXe, Thermo Fisher Scientific) and ToF-SIMS (TofWerk) at 30 kV and 0.1 nA. The thermal stabilities of the cathode materials were assessed using DSC (DSC 214 Polyma, Netzsch). For DSC analysis, the delithiated cathodes were recovered from the half cells and rinsed with a dimethyl carbonate solution. The cathode active material was then scratched from the dried electrode. The charged cathode powder (7 mg) and electrolyte solution (1 M LiPF6 + ethyl methyl carbonate (EMC):FEC = 3:1 (volume ratio) + 0.05 M lithium difluoro(oxalate)borate (LiDFOB), 0.5 µl) were assembled in a high-pressure CrNi steel crucible and packed with a gold-plated copper seal. DSC measurements were carried out by heating the samples from 30 °C to 350 °C at a rate of 5 °C min−1. Accelerating rate calorimetry (ARC; BTC-130, H.E.L.) was employed to assess the thermal stability of pouch-type full cells. For the experiment, pouch-type full cells with different cathodes, for example, NCM50, QO-NM60 and QO-NCM45, were charged to 4.4 V (versus graphite). For comparison with a conventional Ni-rich cathode-based full cell, a full cell featuring NCM90 was charged to 4.2 V (versus graphite), which is the typical cycling condition for conventional LIBs. The components of the pouch-type full cells used in ARC experiments were identical to those for electrochemical testing, but the cell capacity was increased to ~700 mAh to clearly identify the thermal runaway reactions. The ARC tests were performed under the adiabatic condition. During the heat–wait–seek stage, the cells were heated gradually in 5 °C steps and once the thermal equilibrium was reached, the system entered the waiting period that lasted 20 min without external heating. The temperature with the rising rate at 0.04 °C min−1 was selected as T1, which indicates the onset of a battery self-heating. T2, which indicates the starting point of uncontrollable thermal runaway, was determined when the temperature rising rate is at 60 °C min−1. The maximum temperature during the thermal runaway reactions was indicated as T3. A titration method was employed to quantify the residual lithium content on the surface of the cathode material. For this analysis, 5 g of the cathode powder and 100 ml of deionized water were mixed for 5 min using a magnetic stirring bar at 300 rpm. After vacuum filtration, the resulting solution was titrated with 0.1 M hydrochloric acid. The concentration of the residual lithium compounds was calculated by the following formula, where M is the molecular weight and En is the input volume at the nth equivalence point.

Changes in the volumes of pouch seals were monitored using an electronic densimeter (MDS-3000, Alfa Mirage). During the storage-swelling experiments, the pouch seals containing delithiated cathodes and fresh electrolyte (1 M LiPF6 + EMC:FEC = 3:1 (volume ratio) + 0.05 M LiDFOB) (amount of electrolyte (g) = amount of active materials × 3.5) were stored in an oven at 60 °C, and the volume changes were regularly monitored. To investigate the extent of TM dissolution, the cathodes were charged to 4.6 V and stored in 10 ml of fresh electrolyte (1 M LiPF6 + EMC:FEC = 3:1 (volume ratio) + 0.05 M LiDFOB) in a Teflon bottle filled with Ar gas. After storage in an oven at 60 °C for 1, 2 and 4 weeks, the amounts of TM dissolved in the electrolyte solution were determined using inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectroscopy (iCAP 7000 Series, Thermo Fisher Scientific). The extent of surface degradation arising from oxidative decomposition of the electrolyte was investigated using ToF-SIMS (TOF.SIMS-5, ION-TOF) with a Cs+ sputtering gun source (500 eV, 40 nA) in negative mode. For the NEB method with DFT calculation, quasi-ordered and O3-layered structures were modelled based on 2×2×1 O3-type unit cell, whereas the spinel phase was constructed using the structural model reported by Gummow et al.60. Energetically favourable arrangements of transition metal (TM) and Li+ were identified through extensive Coulomb screening using the Supercell code61. Spin-polarized density functional theory (DFT) calculations were performed using the projector augmented-wave method62, as implemented in the Vienna Ab initio Simulation Package63,64,65 The Perdew–Burke–Ernzerhof exchange–correlation functional66 was employed for both geometry and unit cell optimization. Climbing Image Nudged Elastic Band calculations67 with one intermediate image were also performed using Vienna Ab initio Simulation Package, employing the default optimizer. A plane-wave energy cut-off of 520 eV was used for all calculations. The Brillouin zone was sampled using a 1 × 1 × 1 Γ-centred k-point mesh. Electronic and force convergence criteria were set to 10−4 eV and 2 × 10−2 eV Å−1.

Electrochemical tests

To fabricate the electrodes for half- and full-cell tests, the cathode active materials, KS-6, Super-P and polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) were mixed in N-methyl-2-pyrrolidone in a dry room using a mixer (ARE-310, THINKY). For the half- and full-cell electrodes, the slurry mixtures were prepared using active material:KS-6:Super-P:PVDF weight ratios of 90:3.3:2.2:4.5 and 94:1.8:1.2:3, respectively. The slurry was coated on Al foil (current collector) using a doctor blade to obtain a loading of ~4 mg cm−2 for half-cell electrodes. For the full-cell electrodes, the slurry was coated on carbon-coated Al foil to obtain a loading of 14–16 mg cm−2. After drying in an oven (110 °C) to remove any solvent (N-methyl-2-pyrrolidone), the electrodes were roll pressed. The pressed electrodes were punched into circles with a 14-mm diameter for the half cells and into 3 × 5 cm2 rectangles for the full cell. The half cells were assembled in CR2032-type coin cells (Hohsen) using 40-μm-thick Li metal (Honjo metal) as the anode, polypropylene/polyethylene/polypropylene (PP/PE/PP; Celgard 2320, Celgard) as the separator and 1 M LiPF6 + EMC:FEC = 3:1 (volume ratio) + 0.05 M LiDFOB as the electrolyte. The use of this electrolyte solution enables the cells to be tested at high voltages (3.0–4.6 V) by eliminating potential problems associated with electrolyte decomposition and dendrite formation. The electrochemical performances of the cells were tested using a battery-testing system (TOSCAT-3100, TOYO System). The half cells were initially charged/discharged by applying constant C-rates of 0.1 C/0.1 C (18 mA g−1) to obtain the initial capacity and then cycled at charging/discharging C-rates of 0.5 C/1 C at 45 °C in the voltage ranges of 3.0–4.3, 3.0–4.4, 3.0–4.5 and 3.0–4.6 V (vs Li/Li+). The charge–discharge curves of the cathodes at high voltage are obtained on their first cycle, without performing formation cycles at low voltages. The cycling temperature of 45 °C was chosen to quickly and easily screen the best cathode material at a condition that is typical of EV battery operating conditions (25–45 °C). For tests with commercial LiFePO4, the half cells were charged and discharged in the voltage range of 2.5–3.9 V. To fabricate pouch-type full cells, commercial double-side coated mesocarbon microbead artificial graphite (3.1 × 5.1 cm2, ENERTECH) was used as the anode with the same electrolyte and separator as used in the half-cell tests. The areal capacities of the cathodes for the full-cell tests were in the range of 2.8–3.0 mAh cm−2. The capacity ratio between the negative and positive electrodes (N/P) ranged from 1.15 to 1.2. Full-cell tests were cycled at fixed charge and discharge C-rates of 0.8 C and 1 C, respectively, within 3.0–4.4 and 3.0–4.5 V (versus graphite). To test the rate capabilities, the half cells were discharged at increasing C rates (36 (0.2 C), 90 (0.5 C), 180 (1 C), 360 (2 C) and 900 (5 C) mA g−1) whereas C rate for charging fixed at 36 (0.2 C) mA g−1.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and its Supplementary Information.

References

Larcher, D. & Tarascon, J.-M. Towards greener and more sustainable batteries for electrical energy storage. Nat. Chem. 7, 19–29 (2015).

Turcheniuk, K., Bondarev, D., Singhal, V. & Yushin, G. Ten years left to redesign lithium-ion batteries. Nature 559, 467–470 (2018).

Global Supply Chains of EV Batteries (IEA, 2022); https://www.iea.org/reports/global-supply-chains-of-ev-batteries

Schmuch, R., Wagner, R., Hörpel, G., Placke, T. & Winter, M. Performance and cost of materials for lithium-based rechargeable automotive batteries. Nat. Energy 3, 267–278 (2018).

Tarascon, J.-M. & Armand, M. Issues and challenges facing rechargeable lithium batteries. Nature 414, 359–367 (2001).

Cobalt London Metal Exchange (LME, accessed 21 October 2024); https://www.lme.com/en/Metals/EV/LME-Cobalt#

Li, M. & Lu, J. Cobalt in lithium-ion batteries. Science 367, 979–980 (2020).

Park, G.-T. et al. Introducing high-valence elements into cobalt-free layered cathodes for practical lithium-ion batteries. Nat. Energy 7, 946–954 (2022).

Liu, T. et al. Understanding Co roles towards developing Co-free Ni-rich cathodes for rechargeable batteries. Nat. Energy 6, 277–286 (2021).

Nickel reserves: top 8 countries. Investing News Network https://investingnews.com/daily/resource-investing/base-metalsinvesting/nickel-investing/nickel-reserves-by-country/ (2024).

Leading countries based on reserves of cobalt worldwide in 2023 (in metric tons). Statista https://www.statista.com/statistics/264930/global-cobalt-reserves/ (2024).

Share of nickel demand worldwide in 2021 and a forecast for 2040, by end use. Statista https://www.statista.com/statistics/1351631/forecast-global-nickel-demand-share-by-end-use/#statisticContainer (2024).

Sharma, R. Deep-sea mining: economic, technical, technological and environmental considerations for sustainable development. Mar. Technol. Soc. J. 45, 28–41 (2011).

Zhang, R. et al. Compositionally complex doping for zero-strain zero-cobalt layered cathodes. Nature 610, 67–73 (2022).

Zhang, R. et al. Long-life lithium-ion batteries realized by low-Ni, Co-free cathode chemistry. Nat. Energy 8, 695–702 (2023).

Grey, C. P. & Hall, D. S. Prospects for lithium-ion batteries and beyond—a 2030 vision. Nat. Commun. 11, 6279 (2020).

Global price of manganese ore from 2016 to 2022. Statista Research Department https://www.statista.com/statistics/247633/manganese-price-forecast/ (2024).

Grey, C. P. & Tarascon, J.-M. Sustainability and in situ monitoring in battery development. Nat. Mater. 16, 45–56 (2017).

Armstrong, A. R. & Bruce, P. G. Synthesis of layered LiMnO2 as an electrode for rechargeable lithium batteries. Nature 381, 499–500 (1996).

Capitaine, F., Gravereau, P. & Delmas, C. A new variety of LiMnO2 with a layered structure. Solid State Ionics 89, 197–202 (1996).

Lee, W. et al. New insight into Ni-rich layered structure for next-generation Li rechargeable batteries. Adv. Energy Mater. 8, 1701788 (2018).

Sun, Y.-K., Lee, D.-J., Lee, Y. J., Chen, Z. & Myung, S.-T. Cobalt-free nickel-rich layered oxide cathodes for lithium-ion batteries. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 5, 11434–11440 (2013).

Shannon, R. D. Revised effective ionic radii and systematic studies of interatomic distances in halides and chalcogenides. Acta Cryst. A 32, 751–767 (1976).

Park, G.-T. et al. Nano-rods in Ni-rich layered cathodes for practical batteries. Chem. Soc. Rev. 53, 11462–11518 (2024).

Jarvis, K. A., Deng, Z., Allard, L. F., Manthiram, A. & Ferreira, P. J. Atomic structure of a lithium-rich layered oxide material for lithium-ion batteries: evidence of a solid solution. Chem. Mater. 23, 3614–3621 (2011).

Li, H. H. et al. Changes in the cation ordering of layered O3 LixNi0.5Mn0.5O2 during electrochemical cycling to high voltages: an electron diffraction study. Chem. Mater. 19, 2551–2565 (2007).

Li, J., Doig, R., Camardese, J., Plucknett, K. & Dahn, J. R. Measurements of interdiffusion coefficients of transition metals in layered Li–Ni–Mn–Co oxide core–shell materials during sintering. Chem. Mater. 27, 7765–7773 (2015).

Arachi, Y. et al. Li de-intercalation mechanism in LiNi0.5Mn0.5O2 cathode material for Li-ion batteries. Solid State Ion. 176, 895–903 (2005).

Yoon, C. S. et al. Cation ordering of Zr-doped LiNiO2 cathode for lithium-ion batteries. Chem. Mater. 30, 1808–1814 (2018).

Phillips, P. J., Bareño, J., Li, Y., Abraham, D. P. & Klie, R. F. On the localized nature of the structural transformations of Li2MnO3 following electrochemical cycling. Adv. Energy Mater. 5, 1501252 (2015).

Bréger, J. et al. Effect of high voltage on the structure and electrochemistry of LiNi0.5Mn0.5O2: a joint experimental and theoretical study. Chem. Mater. 18, 4768–4781 (2006).

Ryu, H.-H. et al. Capacity fading mechanisms in Ni-rich single-crystal NCM cathodes. ACS Energy Lett. 6, 2726–2734 (2021).

Janek, J. & Zeier, W. G. Challenges in speeding up solid-state battery development. Nat. Energy 8, 230–240 (2023).

Jung, S.-H. et al. Ni-rich layered cathode materials with electrochemo-mechanically compliant microstructures for all-solid-state Li batteries. Adv. Energy Mater. 10, 1903360 (2019).

Bi, Y. et al. Reversible planar gliding and microcracking in a single-crystalline Ni-rich cathode. Science 370, 1313–1317 (2020).

Wang, L., Liu, T., Wu, T. & Lu, J. Strain-retardant coherent perovskite phase stabilized Ni-rich cathode. Nature 611, 61–67 (2022).

Singer, A. et al. Nucleation of dislocations and their dynamics in layered oxide cathode materials during battery charging. Nat. Energy 3, 641–647 (2018).

Ryu, H.-H., Park, K.-J., Yoon, C. S. & Sun, Y.-K. Capacity fading of Ni-rich Li[NixCoyMn1-x-y]O2 (0.6 ≤ x ≤ 0.95) cathodes for high-energy-density lithium-ion batteries: bulk or surface degradation?. Chem. Mater. 30, 1155–1163 (2018).

Kim, U.-H. et al. Heuristic solution for achieving long-term cycle stability for Ni-rich layered cathodes at full depth of discharge. Nat. Energy 5, 860–869 (2020).

Li, B. et al. Constructing “Li-rich Ni-rich” oxide cathodes for high-energy-density Li-ion batteries. Energy Environ. Sci. 16, 1210–1222 (2023).

Gao, X. et al. Achieving high-voltage stability in Li-rich Ni-rich oxides with local W/Ni(Li) superstructure. Adv. Energy Mater. 15, 2402793 (2025).

Zhou, C.-x et al. Formation and effect of residual lithium compounds on Li-rich cathode material Li1.35[Ni0.35Mn0.65]O2. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 11, 11518–11526 (2019).

Zou, G. et al. Improvement of electrochemical performance for Li-rich spherical Li1.3[Ni0.35Mn0.65]O2+x modified by Al2O3. J. Solid State Electrochem. 18, 1789–1797 (2014).

House, R. A. et al. First-cycle voltage hysteresis in Li-rich 3d cathodes associated with molecular O2 trapped in the bulk. Nat. Energy 5, 777–785 (2020).

Liu, T. et al. Origin of structural degradation in Li-rich layered oxide cathode. Nature 606, 305–312 (2022).

House, R. A. et al. Superstructure control of first-cycle voltage hysteresis in oxygen-redox cathodes. Nature 577, 502–508 (2020).

Sathiya, M. et al. Origin of voltage decay in high-capacity layered oxide electrodes. Nat. Mater. 14, 230–238 (2015).

Lu, D., Xu, M., Zhou, L., Garsuch, A. & Lucht, B. L. Failure mechanism of graphite/LiNi0.5Mn1.5O4 cells at high voltage and elevated temperature. J. Electrochem. Soc. 160, A3138–A3143 (2013).

Xu, C. et al. Bulk fatigue induced by surface reconstruction in layered Ni-rich cathodes for Li-ion batteries. Nat. Mater. 20, 84–92 (2021).

Park, G.-T., Ryu, H.-H., Park, N.-Y., Yoon, C. S. & Sun, Y.-K. Tungsten doping for stabilization of Li[Ni0.90Co0.05Mn0.05]O2 cathode for Li-ion battery at high voltage. J. Power Sources 442, 227242 (2019).

Xu, G.-L. et al. Building ultraconformal protective layers on both secondary and primary particles of layered lithium transition metal oxide cathodes. Nat. Energy 4, 484–494 (2019).

Yan, P. et al. Tailoring grain boundary structures and chemistry of Ni-rich layered cathodes for enhanced cycle stability of lithium-ion batteries. Nat. Energy 3, 600–605 (2018).

Lim, J. et al. Origin and hysteresis of lithium compositional spatiodynamics within battery primary particles. Science 353, 566–571 (2016).

Deng, J., Bae, C., Marcicki, J., Masias, A. & Miller, T. Safety modelling and testing of lithium-ion batteries in electrified vehicles. Nat. Energy 3, 261–266 (2018).

Liu, K., Liu, Y., Lin, D., Pei, A. & Cui, Y. Materials for lithium-ion battery safety. Sci. Adv. 4, eaas9820 (2018).

Finegan, D. et al. In operando high-speed tomography of lithium-ion batteries during thermal runaway. Nat. Commun. 6, 6924 (2015).

Hammami, A., Raymond, N. & Armand, M. Runaway risk of forming toxic compounds. Nature 424, 635–636 (2003).

Yao, Y. et al. Hydrometallurgical processes for recycling spent lithium-ion batteries: a critical review. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 6, 13611–13627 (2018).

Or, T., Gourley, S. W. D., Kaliyappan, K., Yu, A. & Chen, Z. Recycling of mixed cathode lithium-ion batteries for electric vehicles: current status and future outlook. Carbon Energy 2, 6–43 (2020).

Gummow, R. J., Liles, D. C. & Thackeray, M. M. Spinel versus layered structures for lithium cobalt oxide synthesised at 400°C. Mater. Res. Bull. 28, 235–246 (1993).

Okhotnikov, K., T. Charpentier, T. & Cadars, S. Supercell program: a combinatorial structure-generation approach for the local-level modeling of atomic substitutions and partial occupancies in crystals. J. Cheminform. 8, 17 (2016).

Blöchl, P.E. Projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 50, 17953 (1994).

Kresse, G. & Hafner, J. Ab initio molecular dynamics for liquid metals. Phys. Rev. B 47, 558 (1993).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficiency of ab initio total energy calculations for metals and semiconductors using a plane-wave basis set. Comput. Mater. Sci. 6, 15–50 (1996).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B 54, 11169 (1996).

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized Gradient Approximation Made Simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865 (1996).

Jónsson, H., Mills, G. & Jacobsen, K. W. in Classical and quantum dynamics in condensed phase simulations (eds Burne, B. J. et al.) 385–404 (World Scientific, 1998).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank C. Han and H. Lee from Daegu Gyeongbuk Institute of Science and Technology (DGIST) for help in the ARC experiment. We also thank M.G. Kim from PAL and J. Kim from Sungkyunkwan University (SKKU) for assistance with XAS experiments and discussions. This work was supported by the Human Resources Development Program (number 20214000000320) of the Korea Institute of Energy Technology Evaluation and Planning (KETEP), funded by the Ministry of Trade, Industry and Energy of the Korean government. This work was also supported by Korea Institute of Energy Technology Evaluation and Planning (KETEP) grant funded by the Korea government (MOTIE) (RS-2024-00398346, ESS Big Data-Based O&M and Asset Management Technical Manpower Training).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

G.-T.P. and Y.-K.S. conceived the ideas and designed the experiments. G.-T.P., N.-Y.P., T.-Y.Y., M.-C.K. and Y.-K.S. synthesized the materials. J.-H.R., S.-J.S. and T.-Y.Y. tested the electrochemical performances. G.-T.P., N.-Y.P., J.-H.R. and S.-J.S. performed the in situ XRD experiment, thermal analysis and post-mortem analyses. G.-T.P., N.-Y.P. and Y.-K.S. analysed the data. G.-T.P. and C.S.Y. performed the TEM analysis. S.B. and P.K. carried out DFT calculation. G.-T.P., C.S.Y. and Y.-K.S. wrote the paper. Y.-K.S. supervised the research. All authors contributed to the discussion and provided feedback on the manuscript. All authors approved the final paper.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Energy thanks Arjun Thapa and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figs. 1–27, Tables 1–5 and Refs. 1–65.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Park, GT., Park, NY., Ryu, JH. et al. Zero-strain Mn-rich layered cathode for sustainable and high-energy next-generation batteries. Nat Energy 10, 1215–1225 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41560-025-01852-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41560-025-01852-3

This article is cited by

-

Ditching nickel for manganese

Nature Energy (2025)