Abstract

Individual building-level approaches are needed to understand the full potential of rooftop photovoltaics (PV) at national and regional scale. Here we use the European Digital Building Stock Model R2025, an open-access building-level database, to assess rooftop solar potential for each of the 271 million buildings in the European Union. The results show that potential capacity could reach 2.3 TWp (1,822 GWp residential, 519 GWp non-residential), with an annual output of 2,750 TWh based on current PV technology. This corresponds to approximately 40% of electricity demand in a 100% renewable scenario for 2050. Already by 2030, over a half of buildings with floor area larger than 2,000 m2 could generate most of remaining capacity for the 2030 target with 355 GWp. Across member states, non-residential rooftops could cover 50% or more of their PV targets, with several exceeding 95%. The open-access building-level database offers practical tools to support better decisions, accelerate renewable energy adoption and promote a more decentralized energy system. It is also an enabler for planners and researchers to further explore energy scenarios with high renewable shares.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Communities need to harness the potential of rooftop photovoltaics (PV) to provide clean energy1 and to enable individuals to become an integral part of the energy transition. Indeed, climate change and the ensuing need to transform the energy system to a sustainable, renewable-based one is a key driver for the rapid growth of solar PV electricity capacity worldwide. At the end of 2024, the cumulative global PV capacity surpassed 2.2 TWp, equivalent to 0.270 kWp per capita worldwide and 0.760 kWp per capita for the European Union2. Progressive net-zero energy-transition scenarios predict that PV generation capacity could increase to up to 80 TWp globally and 5.6 TWp in European Union3. This could result in 8 kWp of PV installed per capita globally and 12.5 kWp in Europe by 2050. As of today, only about 10% of European building roofs are equipped with PV, highlighting a substantial untapped potential to generate clean energy4. Rooftop PV has many benefits5, including CO2 emissions reduction, enhanced rooftop cooling if combined with cool or green roofs, immediate reductions in energy bills and enhanced property values6,7,8. Thus, accelerating PV rooftop deployment should be a priority for policymakers.

Currently, rooftop PV accounts for the main share of the European Union’s solar PV capacity. Data from 2024 show that the residential and non-residential rooftop PV capacities combined represent about 61%—or 215 GWp—of the 339 GWp total installed PV capacity9. This is projected to experience a rapid growth, reaching 400 GW by the end this decade2,10.

Buildings in the European Union are among the highest energy users, accounting for approximately 42% of energy consumption and 36% of energy-related greenhouse gas emissions. Achieving the European Union’s target of climate neutrality by 205011 will require substantial building renovations, as 85−95% of the existing stock is expected to remain in use by 2050. This presents an opportunity to integrate PV installations into building renovations, simultaneously improving their energy efficiency and energy sufficiency12.

The electrification of building energy use, for example, through heat pumps and e-vehicle charging means that PV within or nearby the buildings, coupled with smart energy-management systems (including storage) would not only decrease primary energy demand but also facilitate on-site consumption of the electricity generated. This approach can also reduce electricity transmission losses and lessen stress on the low voltage grid13.

The revised Energy Performance of Buildings Directive (EPBD, 2024) aims to put Europe on track to achieve a fully decarbonized building stock by 2050. Article 10 introduces requirements for various building classes to be ‘solar ready’. Already in 2022 RePowerEU legislation and the EU Solar Energy Strategy outlined a pathway for installing up to 200 GWp additional PV capacity on residential and non-residential rooftops between 2026 and 2030. The European Solar Rooftops Initiative has introduced provisions to enable large-scale deployment of rooftop PV. These include obligations for the installation of rooftop solar energy technologies where technically, economically and functionally feasible for non-residential buildings (NRBs), both public and commercial, with a floor area above 250 m2 as of 2027, and for all new residential buildings (RBs) as of 2030.

Accurate estimation of the PV potential at the building level remains a difficult task, and few comprehensive, publicly available databases provide information on all rooftops across the European Union. Whereas OpenStreetMap (OSM) offers some information on rooftop type (accuracy depends on the users themselves as OSM is a community-based project), it covers only approximately 6% (self-validation) of buildings, which is insufficient for large-scale assessments. This lack of data limits the possibilities to account for different in roof geometries, slopes or orientations, which are critical factors in determining the technical potential of PV installations. Due to this limitation, in the methodology reported here, all PV systems have been modelled as south-facing racks of 20° inclined modules, covering 25% and 40% of the total available building footprint area is considered suitable for PV installations on RBs (and those buildings with no-assigned use) and NRBs14,15, respectively, as explained in Methods.

These percentages were selected based on a combination of suitability factors—including presence of rooftop obstructions, shading and structural limitations—and practical considerations for rooftop PV deployment, such as maintaining access for maintenance, compliance with building codes and ensuring sufficient spacing between PV modules for optimal performance. The current assumptions—such as treating rooftops as if they were flat and setting fixed usable fractions—are necessary for consistent, continent-wide assessments and providing a conservative but practical benchmark until more detailed rooftop data become available.

The present study introduces an update of the open-access Digital Building Stock Model R2025 (DBSM R2025), a building-level vector database that provides a detailed, comprehensive and homogeneous geospatial database of individual buildings across the European Union16. DBSM enables a range of bottom-up energy planning applications from the individual building level to entire neighbourhoods and regional and national scales. Here one such application is demonstrated: the assessment of rooftop PV potential from building to regional and continental scale, for residential and non-residential buildings. The DBSM R2025 dataset represents an important advancement in PV potential assessment, offering a high-resolution, data-driven tool that can greatly enhance PV planning and decision-making. It provides a homogeneous solar cadastre for all 27 EU member states (MS). By providing detailed insights into solar resource availability, and technical constraints, the tool allows stakeholders—including utility companies, policymakers and investors—to identify optimal sites for large- or small-scale PV, rooftop installations or for community-scale projects. Moreover, it supports scenario analysis and feasibility studies, enabling more informed and cost-effective energy planning.

The European Digital Building Stock Model

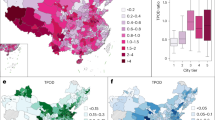

Accurately assessing gross rooftop area at continental level implies working at the level of individual buildings and their rooftops17,18, of which the EU has a complex variety of archetypes19. Moreover, the scarcity of detailed, open-access building datasets poses a significant obstacle20,21, which can potentially give rise to misrepresentation of the characteristics of individual buildings, such as architectural features, roof orientation and shading. This lack of granularity may lead to inaccurate estimates of viable rooftop PV sites18. To address this and support other energy-related policies involving buildings, the Joint Research Centre of the European Commission (JRC) has developed an open-access pan-European Digital Building Stock Model (DBSM)22. The DBSM is a seamless comprehensive geospatial database that enables analyses at the scale of individual buildings in the EU. The 2025 update of DBSM (version R2025) has improved geographic coverage by prioritizing authoritative building footprints with a total of 271 million buildings and total footprint area of approximately 37,370 km2. It also includes estimates of functional use (residential/non-residential), homogeneous height, floor area, compactness (surface to volume ratio) and construction period (for example, Fig. 1e–g). The use of satellite data ensures the widest geographical coverage possible (Supplementary Information Note 1). The smallest footprint area of the DBSM R2025 database is 5m2.

a, Schematic overview of the DBSM Release 2025 (R2025) data conflation process, illustrating the integration of building-level attributes from multiple data sources. b, Three-dimensional representation of the DBSM at neighbourhood and building levels. c, Example of the DBSM R2025 at the country level, shown here for Malta. d, Zoom-in view for Malta illustrating an example of rooftop PV potential electricity generation at the neighbourhood level. e–h, Each building in the DBSM R2025 includes information on: data source (EUBUCCO (EUB), OSM or Microsoft Buildings (MSB)) (e); building age (in 10-year epochs) (f); functional use (residential or non-residential) (g) and building height (h), harmonized using the Global Human Settlement Layer30 and the Urban Atlas31. i, Floor area. Basemap data from Eurostat (https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/gisco/geodata/statistical-units/territorial-units-statistics) under a Creative Commons license CC BY 4.0.

Rooftop PV potential in the EU

The suitable rooftop area for PV installations is significantly smaller than the rooftop footprint area. In the EU, residential buildings represent the largest proportion of the total buildings (87%−97% depending on country), Fig. 2a. This results in approximately 10,000 km2 of usable area for rooftop PV installations in the European Union (Fig. 2a). The corresponding PV potential is 2.3 TWp, producing 2,750 TWh yr−1 with current PV module efficiencies. The aggregation of all rooftop PV parameters at regional level can be found in Supplementary Fig 12.

a, Stacked bar chart showing the percentage distribution of rooftop areas for RBs and NRBs across EU MS (with ISO 3166-1 alpha-2 code; See https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Tutorial:Country_codes_and_protocol_order for country abbreviations). b, Bar plot displaying the total rooftop area of RBs and NRBs in the European Union, and the rooftop area available for PV installations, assuming 25% and 40% of the total area for RBs and NRBs, respectively. c, Aggregated rooftop technical installed capacity (GWp) for residential and non-residential buildings at the EU level across floor area categories (0 m2–250 m2, 250 m2–1,000 m2, 1,000 m2–2,000 m2 and over 2,000 m2), following the EPBD classification. Bar labels denote the corresponding potential electricity generation TWh.

a, Choropleth map of the potential rooftop PV electricity generation, TWh km−2 at Nomenclature of Territorial Units for Statistics classification (NUTS3) regional level for NRBs with floor areas exceeding 250 m2. b, Heat map of the rooftop PV technical capacity potential (GWp) for NRBs across floor area category (0 m2–250 m2, 250 m2–1,000 m2, 1,000 m2–2,000 m2 and over 2,000 m2), following the EPBD classification. Countries are sorted from higher to lower rooftop PV capacity for the 2,000-m2 floor area category. See https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Tutorial:Country_codes_and_protocol_order for country abbreviations. Basemap data in a from Eurostat (https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/gisco/geodata/statistical-units/territorial-units-statistics) under a Creative Commons license CC BY 4.0.

Breaking this down for RBs and NRBs gives 1,822 GWp (2,141 TWh) and 519 GWp (607 TWh), respectively (Fig. 2b). Almost all EU countries have a technical potential exceeding 40 GWp, which corresponds to 32 TWh yr−1 to 60 TWh yr−1 depending on the local solar irradiation. For most (except Cyprus, Finland and Sweden), this electricity generation potential could provide more than 50% of current (2024) electricity consumption (Fig. 4). As the largest and most populated MS, Germany and France have the highest rooftop PV potential (394 TWh and 432 TWh, respectively) offering a capacity to meet more than 80% of their current electricity demand. Several countries could match or exceed their current consumption, notably Greece (78 TWh potential vs 50 TWh consumption), Hungary (58 TWh potential vs 42 TWh consumption) and Romania (101 TWh potential vs 44 TWh consumption).

Bubble size represents the total potential electricity generation per country TWh yr−1, and bubble colour indicates the share of PV potential generated from RBs. See https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Tutorial:Country_codes_and_protocol_order for country abbreviations.

PV production and electricity use at the building level do not necessarily align temporally. However, future electrification of heating, integration of electrified transport and of storage options and flexible demand-side management approaches, can largely close this gap. In addition, initiatives such as energy communities can aggregate demand and production, further reducing temporal mismatch. The DBSM’s building-level data in combination with PV production profiles from the Photovoltaic Geographical Information System (PVGIS)23 can enable the disaggregated analysis these approaches need.

The rooftop PV capacity for NRBs, rises sharply with building size across all EU countries. Large buildings exceeding 2,000 m2 dominate the potential—particularly in Germany, Italy, Spain and the Netherlands—whereas smaller NRBs contribute comparatively little, Fig. 3b. In terms of building usage, RBs with floor areas between 0 m2 and 250 m2 exhibit the highest technical potential, reaching 900 GWp and accounting for 36% of the total potential capacity. The corresponding electricity generation would be 1,018 TWh yr−1 (Fig. 2c), which is the same order of magnitude as the estimate of Gernaat et al.21, who reported a residential rooftop PV electricity generation of 720 TWh yr−1 at the EU level. In most cases such buildings are mainly one- or two-family homes, and their occupiers are in general the most active in adopting PV. The 250 m2–1,000 m2 category are usually apartment buildings or buildings with multiple owners or a mixture of owner–occupiers and tenants. For these, regulatory frameworks and building regulations can hinder the adoption of rooftop PV24.

Buildings with floor areas exceeding 2,000 m2 make significant contributions to the total potential, with RBs and NRBs providing 246 GWp and 355 GWp, respectively. Together, they represent 25% of the total technical PV capacity. Including to this, the category 1,000 m2–2,000 m2, the potential rooftop capacity could exceed 800 GWp.

Solar radiation varies significantly within countries, which also affects the spatial distribution of rooftop photovoltaic (PV) yield. This is reflected in Fig. 3a, which shows the estimated electricity generation per square kilometre, at the regional level (level 3) using the Nomenclature of Territorial Units for Statistics classification (NUTS3). For instance, in Spain, mean annual global horizontal irradiation in southern regions frequently exceeds 37.8 TWh km−2, whereas in northern regions it often falls below 0.18 TWh km−2. Such gradients translate into differences of several hundred full-load hours of PV generation potential per year. These results highlight the necessity of incorporating sub-national variation in solar resource availability into PV deployment strategies, as country-level averages can mask substantial regional disparities with direct implications for technical potential, economic performance and policy design.

Figure 5 relates these estimates of rooftop PV annual electricity generation to high-resolution (1 km × 1 km) annual energy demand data from the EU energy atlas analysis for 201925 (Supplementary Information Note 2). It shows that most EU regions could meet their residential energy needs by installing rooftop PV. However, a few densely populated areas or large urban centres would face shortfalls. Over time the deficit/excess balance can evolve with improvements in PV performance on the one hand and changes in demand due to increasing electrification on the other. Data combinations such as here have great potential to help prioritize areas for rooftop PV installation and for grid investments and informing policy measures to promote cost-effective capacity development.

The map illustrates the estimated spatial balance between potential rooftop PV electricity generation and sectoral energy demand at 1 km × 1 km resolution across the European Union. Sectoral energy demand includes commercial and public services, households, agriculture and forestry and fishing, derived from the Energy Atlas dataset. Regions with positive values indicate a local PV electricity surplus (blue colours), whereas negative values represent a deficit relative to demand (red colours). Basemap data from Eurostat (https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/gisco/geodata/statistical-units/territorial-units-statistics) under a Creative Commons license CC BY 4.0.

DBSM R2025 offers a granular, open-access, building-level dataset suitable for localized analyses. In contrast, recent comparable studies, such as that by Molnár et al.26, provide a macro-scale assessment of aggregated rooftop PV potential at the national level across the EU using the Building Integrated Solar Energy model. The published data from their work is at the national level, as opposed to the building-level resolution of the data published as part of our study. In addition to rooftop PV potential, DBSM R2025 makes available several other building characteristics, such as functional use (residential or non-residential), height, floor area and building age, which enable additional analysis connected to solar cadastres. Furthermore, whereas Molnár et al. used OSM and MSB22 as input data26, DBSM R2025 uses authoritative (cadastral) data as the primary input building dataset (55% of the buildings), with gaps filled using OSM and finally MSB buildings (Fig. 1a). Another key difference lies in the estimation of solar irradiance. In our study, we used the open-access PVGIS tool, which provides long-term hourly solar irradiance time series at geo-located points at a spatial resolution of 5 km. In contrast, the Building Integrated Solar Energy model used by Molnár et al. uses data at a resolution of 100 km (ref. 26).

Implications for short- and medium-term policy goals

Rooftop photovoltaics could play an important role in meeting the future energy needs of the EU, as illustrated in Fig. 6, which compares the RePowerEU 2030 target with the projected 2050 decarbonization pathways. For the latter, two scenarios are considered: the POTEnCIA CETO Scenario27 of 2.2 TWp of PV capacity and Breyer et al.’s 100% renewable solution, which would require 5.6 TWp of PV (12.5 kWp per capita3. Rooftop PV on NRBs alone would cover the planned deployment in 2030 under the REPowerEU policy. Looking to 2050, the rooftop PV technical potential would cover the total PV capacity foreseen in the POTEnCIA CETO scenario, so in practical terms, it could continue to be the largest form of PV deployment in the European Union. In relation to the ambitious 100% RES scenario, rooftop PV could still provide up to 40% of the needed PV capacity, but other forms of PV deployment would predominate.

Comparison of the rooftop rooftop PV technical potential for RBs and NRBs in the European Union with projected PV capacities for 2030 under the REPowerEU target and two 2050 full decarbonization scenarios: Policy-Oriented Tool for Energy and Climate change Impact Assessment (POTEnCIA) of the Clean Energy Technology Observatory (CETO) and 100% Renewable Energy Sources (RES). The figure highlights the extent to which rooftop PV could contribute to achieving EU renewable energy and decarbonization objectives. Bar labels denote the corresponding potential electricity generation TWh.

At the level of individual EU countries, the analysis suggests that many could meet—and in some cases exceed—the PV capacities included in their National Energy and Climate Plans (NECPs) for 2030 using only NRBs (Supplementary Information Note 4). Most MS could cover over 50% of their 2030 targets with rooftop PV from NRB, and several could exceed 95%. Countries such as Cyprus, Finland and Denmark show particularly high rooftop potential relative to their targets. And enabling calculations of total potential capacity, the DBSM is a valuable tool to identify priority areas and for road mapping future developments of rooftop PV. As already noted, in the EU rooftop PV represented an installed capacity of 215 GWp at the end of 2024. Furthermore, the European Solar Rooftop Initiative makes the installation of PV on commercial and public buildings obligatory as of 2026. These data suggest that a logical approach would be to prioritize NRB between now and the end of the decade. Such buildings are easily identified in the DBSM R2025, at a national, regional or local level. Figure 7 presents a scenario for reaching the 2030 target principally using non-residential buildings.

Per capita solar PV installed capacity is shown for each MS, comparing the 2024 status (grey dots) with the 2030 levels projected in the NECPs (square markers). The colour of the squares indicates the percentage of electricity demand coverage achievable using only NRBs. Triangles represent the total technical rooftop PV potential per capita, derived from the DBSM R2025 for both RB and NRB buildings. The colour of the triangles denotes the share of potential coverage of the projected 12.5 kWp per capita rooftop PV target by 2050. NECPs outline each MS’s strategy to meet the EU’s energy and climate targets for 2030; plans for Belgium, Estonia and Poland are still being finalized. See https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Tutorial:Country_codes_and_protocol_order for country abbreviations.

In addition, Fig. 7 presents a breakdown of the PV capacity per capita for the NECP targets, the 100% RES 2050 scenario and the total rooftop PV potential per capita across EU countries. The average non-residential rooftop PV potential per capita is approximately 1,267 W, with most of the countries capable of meeting their 2030 targets only using non-residential buildings. The coverage ratio varies from 45% to exceeding 100% in several cases. The estimated rooftop PV potential corresponds to an average value of 5 kWp per capita in the European Union, which represents around 40% of the amount of PV needed for such a 100% renewable energy scenario. This indicates a coverage of between 27% and 70% of the projected per capita need of these progressive scenarios. It underlines the crucial role of rooftop PV in Europe’s energy transition, showing that even partial utilization of existing rooftop space could substantially contribute to meeting long-term renewable energy targets.

Conclusions

DBSM R2025 is an open-access building-level database containing 271 million geo-located buildings with a total footprint area of 37,370 km2. Here one of its many potential applications is presented: assessment of the rooftop PV potential from building level to continental scale. Detailed insights into solar resource availability and technical constraints are supported by the DBSM, which in addition allows stakeholders—including utility companies, policymakers and investors—to identify optimal sites for large-scale PV plants, rooftop installations, community-scale projects or building-integrated photovoltaics.

This assessment quantifies rooftop PV separately for residential and non-residential buildings at individual building level over the entire European Union and makes the database and the production code publicly available. This provides users with a high level of flexibility to adapt their analysis to any desired technical option or geographical scale.

These estimates indicate an EU-wide rooftop PV technical potential of 2,340 GWp at today’s module efficiency levels, capable of generating around 2,750 TWh yr−1. This is significantly higher than most previous assessments, due primarily to the use of up-to-date building-level data and improved PV module efficiency (22% vs 18% in earlier studies such as Bódis et al.15) but also the used rooftop area coverage factors. The results are consistent with the findings from Molnár et al.26, which estimated a rooftop PV potential electricity generation of about 2,700 TWh yr−1 (Supplementary Information Note 3).

This study adds open-access building-based resolution and code, enabling fully replicable bottom-up analyses from individual buildings to neighbourhoods, cities and continent-wide assessments. The benefits of increasing efforts to exploit the rooftop resource are evident. The results show that already for 2030 over 50% of the PV capacity foreseen in the individual plans of the EU countries could be met just from PV on non-residential rooftops in most cases. Full exploitation of the rooftop PV technical potential would exceed the PV needs under the POTEnCIA CETO net-zero scenario for 2050 and make a substantial contribution to a 100% renewables scenario for the EU energy system.

This analysis is considered conservative, in terms of percentage of rooftop area deemed suitable for PV installation and the power density, which is largely determined by the PV module efficiency. Also, although the most favourable orientation (south facing) for PV systems is assumed, an analysis using less favourable east or west orientations showed a maximum reduction of 15% in electricity generation from the ideal south-facing case. This could be compensated economically by higher self-consumption or increased network value outside the normal peak production hours for solar PV.

This study also underlines the importance of rooftop PV to the fairness and citizen involvement dimensions of the EU’s energy transition. Residential buildings represent the largest proportion of the total buildings (87% to 97% depending on country). Non-residential buildings, with larger footprints, add substantial opportunities, with fewer administrative hurdles to install rooftop PV. NRB offer added advantages since their owners typically have a longer-term investment perspective. Occupiers have more possibilities to optimize self-consumption, especially with the additional use of batteries (either stationary or in electric vehicles).

DBSM R2025, with its vector-based resolution allows precise spatial analyses, whereas the open-access code ensures transparency and flexibility, allowing users to tailor PV potential assessments to specific scenarios, technical configurations or regional requirements. In addition, DBSM R2025 can provide a standardized reliable input data for future research, helping to fill gaps in the literature on building-level PV potential across Europe. DBSM can also be integrated into broader renewable energy planning frameworks, supporting energy mix optimization, grid impact assessments and evidence-based policy development. By identifying regions with high PV potential, the tool can foster the growth of renewable energy communities, encourage public–private partnerships and support decentralized energy initiatives, empowering municipalities, cities and local stakeholders to plan sustainable energy strategies tailored to their needs. In addition, it could support community solar projects, enabling multiple households or businesses share the benefits of a single PV installation.

In possible future analyses, combining the granular building data with hourly PV production estimates from PVGIS (either long-term time series or based on a typical meteorological year) with the corresponding hourly electricity demand can create opportunities for communities, developers/traders to realize flexibility in demand-side management and energy storage. Beyond practical applications, DBSM R2025 is an excellent tool for future research and innovation but also for educational purposes allowing scenario analyses under different technical configurations or future climate projections

Methods

The estimation of the rooftop footprint area per building is performed using the DBSM R2025. The usable area for PV installation is lower than the footprint area due to several factors such as module spacing, unfavourable roof orientations, obstructions from technical installations (for example, chimneys, aerials and air conditioning units) and shading from surrounding structures. Because open-access data on roof types is either unavailable or incomplete across countries (with OpenStreetMap offering only 6% completeness at the EU level), the following significant simplifications have been made: (1) all residential buildings were modelled as having a 20° pitched roof side facing south. The PV installations were limited to 25% of the total rooftop area, as described in Rodríguez et al.14 and Bódis et al.15, (2) all non-residential buildings have been modelled as having a flat roof (most commercial buildings do have flat roofs), but in this case the PV installations were set at 40% of the total rooftop area, as described in Mainzer et al.28 and Ghaleb et al.29.

The defined PV system configuration for both building types is free-standing racks oriented south at an inclination angle of 20°, consistent with the international International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC) 61853 standard for the energy rating of PV modules (Supplementary Information Note 5). A 22% module efficiency is assumed. Spacing between modules and module racks is taken into account in the 25% or 40% installation fraction described above, appropriately to the building classification. The above simplifications provide a conservative baseline for estimating both available rooftop area and module efficiency, recognizing that these technologies are evolving and likely to improve over time. Whereas this assessment has been carried out at a pan-European scale, the percentage of usable rooftop area should be validated through local or case-specific studies to account for variations in building typologies, structural constraints, and urban context.

The annual energy yield (kWh kWp−1 yr−1) for each building geolocation across the European Union was estimated using PVGIS, a free-access tool developed by the European Commission’s Joint Research Centre (JRC). The chosen simplified PV system configuration is not always the optimal one, nor necessarily feasible, depending on location and roof type. Many roofs, especially those of RBs, have complex roof configurations and multiple possible orientations. As this information is currently unknown for all buildings in the database—and no open-access rooftop-type database exists for the entire European Union—it is important to validate the simplification that has been made regarding the defined one-size-fits-all PV installation approach. To quantify the impact of the assumptions a sensitivity analysis was performed at 12 European locations chosen over a range of climate types (Supplementary Information Note 6, and Supplementary Fig 2), from subtropical climates to circumpolar climates, according to the European Environment Agency definitions.

The same PV system used in this study was analysed in these specific locations, modifying the inclination angle from 0∘ (horizontal plane) to 90∘ (vertical plane) at steps of 5∘, and the orientation or azimuth angle from −180∘ (north) to 180∘, at steps of 10∘ (Supplementary Note 6). East being −90∘, south 0∘ and west 90∘. Various parameters have been analysed including the average annual PV production (kWh kWp−1), in-plane irradiation (kWh m−2) and PV performance (Supplementary Fig. 2d, example from one location point, Paris). The results show that the choice of a south-facing fixed PV system with 20∘ inclination angle is reasonable, with the PV production being very close to that obtained for the optimal configuration at every location.

For the east- or west-facing PV systems, the PV production would be, on average over the 12 locations, only 15% lower than the results from a south-facing PV system. For orientations within 45∘ of due south, this difference decreases to a maximum of only 5% lower PV output. The choice of 20∘ inclination angle is also conservative, because in most cases this is below the optimal angle, and indeed in practice both effects (orientation and inclination) will often compensate each other. Given our overall conservative approach to rooftop area usage (25% for RBs), these differences are not considered highly significant, and the use of a standard PV system configuration will provide acceptably conservative results. For the case of NRBs, the sensitivity analysis is also valid, but in this case, because these buildings are more commonly equipped with flat roofs, there is more flexibility in the PV system design and the 40% area usage is also considered acceptably conservative. All the results from the multiple configurations (orientation and inclination angles) at the 12 selected locations are shown in the Supplementary Information (Supplementary Note 6).

Data availability

The DBSM R2025 dataset, containing building-level information for each EU country, is available for download as a GeoPackage for each EU country from the JRC Data Catalogue at https://data.jrc.ec.europa.eu/collection/id-00382. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

To facilitate reproducibility, the full workflow used to generate DBSM R2025 and compute the PV potential per building is available at https://code.europa.eu/jrc-dbsm/dbsm. This code enables users to reproduce the calculations, adapt the methodology to new regions or perform scenario analyses under different technical configurations or climate projections. The resulting solar rooftop potential estimates from this analysis are incorporated in DBSM R2025 on the JRC Data Catalogue under the Open Database License ODbL.

Change history

28 January 2026

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41560-026-01991-1

References

Zhang, Z., Qian, Z., Chen, M. et al. Worldwide rooftop photovoltaic electricity generation may mitigate global warming. Nat. Clim. Change 15, 393–402 (2025).

Jäger-Waldau, A. Pv snapshot 2025. EPJ Photovoltaics 16, 22 (2025).

Breyer, C. et al. Reflecting the energy transition from a european perspective and in the global context—relevance of solar photovoltaics benchmarking two ambitious scenarios. Prog. Photovoltaics Res. Appl. 31, 1369–1395 (2022).

Kapsalis, V. et al. Bottom-up energy transition through rooftop pv upscaling: remaining issues and emerging upgrades towards nzebs at different climatic conditions. Renewable Sustain. Energy Transition 5, 100083 (2024).

Faes, A., Virtuani, A., Quest, H. et al. Building-integrated photovoltaics. Nat. Rev. Clean Technol. 1, 333–350 (2025).

Valencia-Caballero, D., Bouchakour, S., Luna, A. et al. Experimental energy performance assessment of a bifacial photovoltaic system and effect of cool roof coating. J. Build. Eng. 80, 108009 (2023).

Maurer, B., Lienert, J. & Cook, L. M. Comparing PV-green and PV-cool roofs to diverse rooftop options using decision analysis. Build. Environ. 245, 110922 (2023).

Simpson, C. H., Brousse, O., Taylor, T. et al. Modeled temperature, mortality impact and external benefits of cool roofs and rooftop photovoltaics in london. Nat. Cities 1, 751–759 (2024).

European electricity review 2024. Ember Climate https://ember-energy.org/latest-insights/european-electricity-review-2024/ (2024).

EU Market Outlook 2024–2028 (SolarPower Europe, 2024).

2050 long-term strategy: Climate strategies and targets. European Commission https://climate.ec.europa.eu/eu-action/climate-strategies-targets/2050-long-term-strategy_en (2024).

Cui, Y. & Zhang, X. Research and analysis of energy consumption and energy saving in buildings based on photovoltaic photothermal integration. Sci. Rep. 14, 923 (2024).

Guo, R., Meunier, S., Protopapadaki, C. & Saelens, D. A review of european low-voltage distribution networks. Renewable Sustain. Energy Rev. 173, 113056 (2023).

Romero Rodríguez, L., Duminil, E., Sánchez Ramos, J. & Eicker, U. Assessment of the photovoltaic potential at urban level based on 3D city models: a case study and new methodological approach. Solar Energy 146, 264–275 (2017).

Bódis, K., Kougias, I., Jäger-Waldau, A., Taylor, N. & Szabó, S. A high-resolution geospatial assessment of the rooftop solar photovoltaic potential in the European Union. Renewable Sustain. Energy Rev. 114, 109309 (2019).

EU digital building stock model update including satellite-based attributes (DBSM r2025). EU JRC https://data.jrc.ec.europa.eu/dataset/a601a4a8-9289-4fc4-983a-25d54f957f3a (2025).

Joshi, S., Zakeri, B., Mittal, S. et al. Global high-resolution growth projections dataset for rooftop area consistent with the shared socioeconomic pathways, 2020–2050. Sci. Data 11, 563 (2024).

Walch, A., Castello, R., Mohajeri, N. & Scartezzini, J. Big data mining for the estimation of hourly rooftop photovoltaic potential and its uncertainty. Appl. Energy 262, 114404 (2020).

Yang, H. L., Lunga, D. & Yuan, J. Toward country scale building detection with convolutional neural network using aerial images. In 2017 IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium (IGARSS) 870–873 (IEEE, 2017).

Defaix, P. R., van Sark, W. G. J. H. M., Worrell, E. & de Visser, E. Technical potential for photovoltaics on buildings in the eu-27. Solar Energy 86, 2644–2653 (2012).

Gernaat, D. E. H. J., de Boer, H. S., Dammeier, L. C. & van Vuuren, D. P. The role of residential rooftop photovoltaic in long-term energy and climate scenarios. Appl. Energy 279, 115705 (2020).

Martinez, A. et al. DBSM R2025: EU Digital Building Stock Model Update Including Satellite-based Attributes—A New Version of the EU Digital Building Stock Model Including Authoritative Footprints and Per-building Estimates for Building Height, Compactness, Construction Epoch and Use (Publications Office of the European Union, 2025); https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2760/0629989

Photovoltaic Geographical Information System (PVGIS). European Commission, Joint Research Centre https://joint-research-centre.ec.europa.eu/photovoltaic-geographical-information-system-pvgis_en (2025).

Jäger-Waldau, A. et al. Self-consumption of electricity produced with photovoltaic systems in apartment buildings—update of the situation in various IEA PVPS countries. In 47th IEEE Photovoltaic Specialists Conference (PVSC) 0938–0950 (IEEE, 2020).

Hidalgo Gonzalez, I. & Uihlein, A. High-resolution Energy Atlas (Publications Office of the European Union, 2023).

Molnár, G., Cabeza, L. F., Chatterjee, S. & Ürge Vorsatz, D. Modelling the building-related photovoltaic power production potential in the light of the EU’s solar rooftop initiative. Appl. Energy 360, 122708 (2024).

Neuwahl, F. et al. Clean Energy Technology Observatory: POTEnCIA CETO 2024 Scenario (Publications Office of the European Union, 2024); https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2760/1473321

Mainzer, K. et al. A high-resolution determination of the technical potential for residential-roof-mounted photovoltaic systems in germany. Solar Energy 105, 715–731 (2014).

Ghaleb, B. & Asif, M. Application of solar PV in commercial buildings: utilizability of rooftops. Energy Build. 257, 111774 (2022).

Global human settlement layer (GHSL-BU H2023). Copernicus Land Monitoring Service https://human-settlement.emergency.copernicus.eu/ghs_buH2023.php (2023).

Urban Atlas. Copernicus Land Monitoring Service (2018); https://land.copernicus.eu/en/products/urban-atlas

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank T. Sample for his discussions and feedback throughout the development of this work and O. Gounari for her support in running the PVGIS simulations. We also thank C. Maduta for insightful discussions related to the Energy Performance of Buildings Directive (EPBD). The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent an official position of the European Commission.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

G.K.: conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, data curation, software, investigation, validation, visualization and writing–original draft. R.K.: conceptualization, methodology, investigation and writing–review and editing. N.T.: conceptualization, methodology, investigation and writing–review and editing. A.M.G.-A.: investigation, sensitivity analysis, visualization and writing–review and editing. S.S.: writing–review and editing. A.M.M.: review and editing. C.T.: writing–review and editing. A.J.-W.: writing–review and editing.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Notes 1–6, Tables 1–4, Figs. 1–12 and references.

Source data

Source Data Fig. 2

Excel with all the necessary data to reproduce figures in Fig. 2. Sheet named fig2a and fig2b.

Source Data Fig. 3

Excel with all the necessary data to reproduce figures in Fig. 3. Sheet named fig3.

Source Data Fig. 4

Txt file to reproduce Fig. 4.

Source Data Fig. 7

Txt file to reproduce Fig. 7.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kakoulaki, G., Kenny, R., Taylor, N. et al. Mapping Europe’s rooftop photovoltaic potential with a building-level database. Nat Energy (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41560-025-01947-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41560-025-01947-x