Abstract

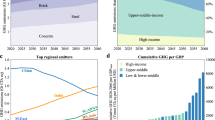

The production of materials is an important source of greenhouse gas emissions. To reduce emissions, policies aim to enhance material efficiency and the circular economy, but our understanding of the dynamics of material-related greenhouse gas emissions is limited. Here, I quantify the greenhouse gas emissions from material production and the carbon footprint of materials in industries that are the first users of materials, and in final consumption, using a multiregional input–output model of the global economy and the hypothetical extraction method. From 1995 to 2015, greenhouse gas emissions from just material production increased by 120%, with 11 billion tons of CO2-equivalent emitted in 2015. As a proportion of global emissions, material production rose from 15 to 23%. China accounted for 75% of the growth. In terms of the first use of materials, two-fifths of the carbon footprint of materials is attributed to construction, and two-fifths to the manufacturing of machinery, vehicles and other durable products. Overall, the replacement of existing or formation of new capital stocks now accounts for 60% of material-related emissions. Policies that address the rapidly growing capital stocks in emerging economies therefore offer the best prospect for emission reductions from material efficiency.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$32.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $21.58 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

A public version of EXIOBASE 3 is available on Zenodo at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3583071. The public version differs slightly from the version that was used in the present research, which makes use of proprietary third-party energy data from the IEA. The private version of the data is available from the author upon request by anybody who has obtained a licence to the IEA Energy Statistics and Energy Balances. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

MatLab code is available on Zenodo at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.4280697.

References

Fischedick, M. et al. in Climate Change 2014: Mitigation of Climate Change (eds Edenhofer, O. et al.) Ch. 10.3 (IPCC, Cambridge Univ. Press, 2014).

International Energy Agency. Energy Technology Perspectives 2017 (OECD, 2017).

Allwood, J. M., Cullen, J. M. & Milford, R. L. Options for achieving a 50% cut in industrial carbon emissions by 2050. Environ. Sci. Technol. 44, 1888–1894 (2010).

Worrell, E. & Carreon, J. R. Energy demand for materials in an international context. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. A 375, 20160377 (2017).

Allwood, J. M., Ashby, M. F., Gutowski, T. G. & Worrell, E. Material efficiency: providing material services with less material production. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. A 371, 20120496 (2013).

Worrell, E., Allwood, J. M. & Gutowski, T. G. The role of material efficiency in environmental stewardship. Annu. Rev. Env. Resour. 41, 575–598 (2016).

Scott, K., Giesekam, J., Barrett, J. & Owen, A. Bridging the climate mitigation gap with economy‐wide material productivity. J. Ind. Ecol. 23, 918–931 (2019).

Stahel, W. R. The circular economy. Nature 531, 435–438 (2016).

Geng, Y., Sarkis, J. & Bleischwitz, R. How to globalize the circular economy. Nature 565, 153–155 (2019).

Zhu, J., Fan, C., Shi, H. & Shi, L. Efforts for a circular economy in china: a comprehensive review of policies. J. Ind. Ecol. 23, 110–118 (2019).

Material Efficiency in Clean Energy Transitions (IEA, 2019).

Pauliuk, S., Arvesen, A., Stadler, K. & Hertwich, E. G. Industrial ecology in integrated assessment models. Nat. Clim. Change 7, 13–20 (2017).

Hertwich, E. G. et al. Material efficiency strategies to reducing greenhouse gas emissions associated with buildings, vehicles, and electronics – a review. Environ. Res. Lett. 14, 043004 (2019).

Stadler, K. et al. EXIOBASE3 - developing a time series of detailed environmentally extended multi-regional input–output tables. J. Ind. Ecol. 22, 502–515 (2018).

Wiedmann, T. O. & Lenzen, M. Environmental and social footprints of international trade. Nat. Geosci. 11, 314–321 (2018).

Malik, A., McBain, D., Wiedmann, T. O., Lenzen, M. & Murray, J. Advancements in input–output models and indicators for consumption‐based accounting. J. Ind. Ecol. 23, 300–312 (2019).

Dietzenbacher, E. & Lahr, M. L. Expanding extractions. Econ. Syst. Res. 25, 341–360 (2013).

Duarte, R., Sánchez-Chóliz, J. & Bielsa, J. Water use in the Spanish economy: an input–output approach. Ecol. Econ. 43, 71–85 (2002).

Dietzenbacher, E., van Burken, B. & Kondo, Y. Hypothetical extractions from a global perspective. Econ. Syst. Res. 31, 505–519 (2019).

Södersten, C.-J. H., Wood, R. & Hertwich, E. G. Endogenizing capital in MRIO models: the implications for consumption-based accounting. Environ. Sci. Technol. 52, 13250–13259 (2018).

Hertwich, E. G. & Wood, R. The growing importance of scope 3 greenhouse gas emissions from industry. Environ. Res. Lett. 13, 104013 (2018).

Lenzen, M. Double-counting in life cycle calculations. J. Ind. Ecol. 12, 583–599 (2008).

Dente, S. M. R. et al. Effects of a new supply chain decomposition framework on the material life cycle greenhouse gas emissions—the Japanese case. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 143, 273–281 (2019).

Dente, S. M. R., Aoki-Suzuki, C., Tanaka, D. & Hashimoto, S. Revealing the life cycle greenhouse gas emissions of materials: the Japanese case. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 133, 395–403 (2018).

Cabernard, L., Pfister, S. & Hellweg, S. A new method for analyzing sustainability performance of global supply chains and its application to material resources. Sci. Total Environ. 684, 164–177 (2019).

Le Quéré, C. et al. Global carbon budget 2018. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 10, 2141–2194 (2018).

Huang, B. et al. Building material use and associated environmental impacts in China 2000–2015. Environ. Sci. Technol. 52, 14006–14014 (2018).

Cai, W., Wan, L., Jiang, Y., Wang, C. & Lin, L. Short-lived buildings in China: impacts on water, energy, and carbon emissions. Environ. Sci. Technol. 49, 13921–13928 (2015).

Kawase, K. China’s housing glut casts pall over the economy. Nikkei Asia https://asia.nikkei.com/Spotlight/The-Big-Story/China-s-housing-glut-casts-pall-over-the-economy (2019).

Guan, D. et al. Structural decline in China’s CO2 emissions through transitions in industry and energy systems. Nat. Geosci. 11, 551–555 (2018).

Moynihan, M. C. & Allwood, J. M. Utilization of structural steel in buildings. Proc. R. Soc. A 470, 20140170 (2014).

Heeren, N. & Hellweg, S. Tracking construction material over space and time: prospective and geo-referenced modeling of building stocks and construction material flows. J. Ind. Ecol. 23, 253–267 (2019).

Müller, D. B. et al. Carbon emissions of infrastructure development. Environ. Sci. Technol. 47, 11739–11746 (2013).

Hertwich, E. G., Lifset, R., Heeren, N., Ali, S. & Pauliuk, S. Resource Efficiency and Climate Change: Emission Reductions From Material-Efficient Homes and Cars (United Nations Environment Programme, 2020).

Swilling, M. et al. The Weight of Cities: Resource Requirements of Future Urbanization (International Resource Panel, United Nations Environment Programme, 2018).

Giljum, S., Bruckner, M. & Martinez, A. Material footprint assessment in a global input–output framework. J. Ind. Ecol. 19, 792–804 (2015).

Wiedmann, T. O. et al. The material footprint of nations. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 112, 6271–6276 (2015).

Hertwich, E. G. & Peters, G. P. Carbon footprint of nations: a global, trade-linked analysis. Environ. Sci. Technol. 43, 6414–6420 (2009).

Nuss, P. & Eckelman, M. J. Life cycle assessment of metals: a scientific synthesis. PLoS ONE 9, e101298 (2014).

van der Voet, E. et al. Environmental Risks and Challenges of Anthropogenic Metals Flows and Cycles (United Nations Environment Programme, 2013).

Stadler, K. et al. EXIOBASE 3 (Norwegian University of Science and Technology, 2019); https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3583071

World Mineral Statistics (BGS, 2018).

Reichl, C., Schatz, M. & Zsak, G. World Mining Data Vol. 29 (Austrian Federal Ministry of Agriculture, Regions and Tourism, 2014).

World Energy Statistics (Edition 2016) (IEA, 2016); https://doi.org/10.1787/03a28cba-en

Xi, F. et al. Substantial global carbon uptake by cement carbonation. Nat. Geosci. 9, 880–883 (2016).

Chen, Z.-M. et al. Consumption-based greenhouse gas emissions accounting with capital stock change highlights dynamics of fast-developing countries. Nat. Commun. 9, 3581 (2018).

Schultz, S. Approaches to identifying key sectors empirically by means of input–output analysis. J. Dev. Stud. 14, 77–96 (1977).

Zhang, L., Liu, B., Du, J., Liu, C. & Wang, S. CO2 emission linkage analysis in global construction sectors: alarming trends from 1995 to 2009 and possible repercussions. J. Clean. Prod. 221, 863–877 (2019).

He, W., Wang, Y., Zuo, J. & Luo, Y. Sectoral linkage analysis of three main air pollutants in China’s industry: comparing 2010 with 2002. J. Environ. Manage. 202, 232–241 (2017).

Owen, A. Techniques for Evaluating the Differences in Multiregional Input–Output Databases (Springer, 2017).

Steen-Olsen, K., Owen, A., Hertwich, E. G. & Lenzen, M. Effects of sector aggregation on CO2 multipliers in multiregional input–output analyses. Econ. Syst. Res. 26, 284–302 (2014).

Rodrigues, J. F. D., Moran, D., Wood, R. & Behrens, P. Uncertainty of consumption-based carbon accounts. Environ. Sci. Technol. 52, 7577–7586 (2018).

Acknowledgements

Language editing by A. Devismes. The work was conducted as part of the project ‘Resource efficiency and climate change’ of the International Resource Panel.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

E.G.H. designed the research, conducted the calculations, interpreted the findings and wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The author declares no competing interests.

Additional information

Peer review information Primary Handling Editor: Rebecca Neely.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Extended Data Fig. 1 Carbon footprint of the production of individual materials, compared to global CO2 emissions.

Greenhouse gas emissions in the production of materials over the period 1995-2015. Materials are listed as represented in the input-output database EXIOBASE. For each material, emissions associated with the input of other materials are included.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Carbon footprint of investment and consumption.

Production of consumer goods and services as well as investment products needs both direct inputs of materials with which these goods and services are produced, and the use of a capital stock in the form of buildings, equipment, machinery, and vehicles which is being depreciated in the process. The use of capital refers to materials that were produced in earlier years. Figure 2 showed the net investment. Here, the focus is in gross fixed capital formation, which is comprised of net investment and reinvestment (replacement of capital that has been depreciated in the given year). The input to consumption has grown by 64%, the input to investment by 170%.

Extended Data Fig. 3 Materials-related GHG emissions according to production- and consumption-based accounts, and net trade.

GHG emissions by the country in which materials or their inputs are produced and emissions occur (a), the country in which final consumption relying on these materials happens (b), and net trade (c) that is, the difference between (a) and (b). China dominates export, followed by Brazil, Russia, Indonesia, Turkey and South Africa (BRITS). Europe and North America are the primary importers. The growth in both the production and consumption of materials was concentrated in China and the developing countries represented in the Rest of World.

Extended Data Fig. 4 Matrices used in the hypothetical extraction method.

Columns represent inputs, and rows outputs of the input-output system.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Data 1

Detailed results of the hypothetical extractions modelling.

Supplementary Table 1

Material required for the production of other materials.

Source data

Source Data Fig. 1

Data points represented in Fig. 1.

Source Data Fig. 2

Entire time series of the data represented in Fig.2.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 1

Data points represented in Fig. ED1.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 3

Data points represented in Fig. ED2.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 2

Data points represented in Fig. ED3.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 4

Drawing represented in Fig. ED4.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hertwich, E.G. Increased carbon footprint of materials production driven by rise in investments. Nat. Geosci. 14, 151–155 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41561-021-00690-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41561-021-00690-8

This article is cited by

-

Consumption inequalities in material use undermining resources sustainability

Nature Sustainability (2026)

-

Changing times: does the critical success factors boosting green transition of SMEs remain unchanged?

Journal of Innovation and Entrepreneurship (2025)

-

Occupational carbon footprints and exposure to climate transition risks

Nature Communications (2025)

-

Doubling of the global freshwater footprint of material production over two decades

Nature Sustainability (2025)

-

Carbon footprint of the construction sector is projected to double by 2050 globally

Communications Earth & Environment (2025)