Abstract

The dynamic interplay between microbial communities and sediment transport shapes continental landscapes and influences particulate matter fluxes across the Earth’s surface. Microbial colonization transforms individual sediment grains into aggregates with intricate and varied morphologies, complicating sediment transport. However, current models often simplify this morphological complexity, assuming that aggregates experience fluid drag equal to that of smooth spheres or idealized shapes. Here we apply an X-ray micro-computed tomography method combined with computational fluid dynamics simulations to analyse aggregate morphology at high spatial resolution and determine the relationship with drag. Instead of aggregate size or gross shape being the primary controls on drag, we find that microbial colonization alters the fine-scale aggregate morphology and increases drag by factors of 1–3 compared with smooth surfaces. We propose a morphology-corrected drag law that accounts for this complexity, reconciling the differences in drag across diverse aggregates. Our findings suggest that a shift from focusing on gross scale variabilities (size or gross shape) to fine-scale morphologies could enable greater accuracy in transport predictions, and improve understanding of microbially colonized aggregates in fluvial, coastal and oceanic systems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Aquatic microorganisms often inhabit sediment particle surfaces, aggregating various particles, cells, organic matter and pollutants1. This widespread microbial colonization dominates aquatic systems worldwide2,3, profoundly impacting biogeochemical processes such as global carbon and nutrient cycles, river delta formation, coastal wetland restoration and pollutant transport in rivers, lakes and oceans and across Earth’s surfaces4,5,6. Hence, accurately predicting microbially mediated sediment transport is crucial. Many models rely on conventional transport laws that are based on assumptions of simple size dependency7 to predict the vertical and lateral fluxes of organic and inorganic matter.

However, a set of counter-intuitive observations challenge this paradigm: settling velocities remain nearly constant despite increases in aggregate size by up to four orders of magnitude6,8; less than 1% of in situ marine aggregates have positive relationships between size and settling velocities9; sediment beds with similar particle size distributions exhibit varying stabilities when colonized by microorganisms to different extents10; and microbial colonization in different states leads to divergent bedform development11,12. These deviations are often attributed to microbial alterations in aggregate density and adhesion to the bed when microbial mats are present13,14, but a crucial factor is overlooked: the complex and variable morphologies established by microbial colonization and the subsequent alteration of drag.

Microbial cells (bacteria, algae and fungi) secrete copious amounts of sticky organic matter (for example, transparent exopolymer particles and extracellular polymeric substances)1. Unlike the seabed, where microbial substances can form thick, smooth mat layers that reduce bed roughness, near-bed turbulence and drag12,15, suspended particles experience frequent hydrodynamic disturbances, aggregate break-up and reaggregation. These conditions inhibit the development of a uniform, smooth mat layer10,11. Instead, the microbial substances develop into organic patches, streamers, multi-layered coatings and protrusions across sediment particle/aggregate surfaces, creating more rough, intricate and irregular morphologies at multiple scales (Fig. 1a(i)–(iv)). Enhanced drag is often observed on microbially colonized particles in suspension16,17,18. Despite the observable morphological complexities (Fig. 1a(i)–(iv)), existing drag laws for microbially colonized particles rely on overly simplistic assumptions, treating them as smooth spheres or simplified shapes (Supplementary Table 1)16,19,20,21. Consequently, most studies focus on gross particle properties such as size and overall shape (for example, long, intermediate and short lengths), neglecting finer-scale structural complexities. Addressing this gap requires a direct and high-resolution investigation into the drag acting on these complex structures to precisely elucidate the connections between aggregate morphology and drag. Such progress has been hampered by long-standing challenges in high-resolution and three-dimensional (3D) imaging of microbial metabolites in sediment aggregates in their hydrated states22. Recently, we overcame this challenge by developing a wet staining method using X-ray micro-computed tomography (micro-CT)23. Combined with computational fluid dynamics (CFD) simulations, we estimated the fluid drag exerted on individual aggregate structures across a range of Reynolds numbers (Re) from less than 0.1 to 100 (Methods).

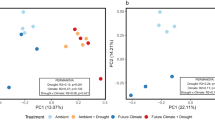

a, Example 3D aggregate morphologies characterized by micro-CT imaging, illustrating variance as microbial colonization intensifies. The four states of microbial colonization are represented as follows: fb = 0–0.25 (i), 0.25–0.50 (ii), 0.50–0.75 (iii) and 0.75–1.00 (iv). The sediment particles are shown in yellow and microbial substances are shown in purple. b, Corresponding \({C}_{\mathrm{D}}^{* }\) distribution curves across the four states of microbial colonization, shifting towards higher values as microbial colonization increases. The percentage of aggregates with \({C}_{\mathrm{D}}^{* }\) values greater than 1.5 increases from 18% (fb = 0–0.25) to 66% (fb = 0.75–1.00). The frequency distribution curves were obtained by analysing 1,618 datasets.

With this new methodology, we assessed the impacts of these complex morphologies on drag by comparing the drag exerted on rough and irregular aggregates with that on volume-equivalent smooth spheres. We scanned and analysed diverse aggregates collected under different laboratory conditions and from various field sites. These aggregates were categorized into four states of microbial colonization according to their volumetric fraction of microbial substances (fb): 0–0.25, 0.25–0.50, 0.50–0.75 and 0.75–1.00 (Fig. 1a(i)–(iv)). The microbial fraction is defined as fb = VbVt, where Vb is the volume of microbial substances encapsulated within an individual aggregate and Vt is the total volume of the aggregate. Both Vb and Vt were directly measured using micro-CT imaging of 3D aggregate structures.

Drag alterations caused by microbial colonization

Our results show that microbial colonization manifests in distinct morphologies across the four states of colonization (Fig. 1a(i)–(iv)). For the poorly colonized aggregates (fb = 0–0.25), a relatively small amount of organic matter (for example, extracellular polymeric substances) is secreted, forming tiny, discrete colonies that are heterogeneously distributed across the surfaces of the sediment grains (Fig. 1(a1)). These microbial colonies frequently protrude into water but to a moderate degree, complicating the interfaces between particles and water without markedly altering the gross shape (that is, transforming aggregates from rounded grains to elongated or flat shapes). As microbial colonization intensifies (fb = 0.25–0.50), facilitated by both the internal environment of the colonies and the surrounding environment, individual microbial colonies grow and connect, forming enlarged and thickened patches (Fig. 1a(ii)). These patches do not form a homogeneous coating that wraps around the whole sediment particle, but instead appear as multi-layered branches or mushrooms with irregular, rough morphologies intruding into the water from different angles. In this stage, substantial changes to the gross shape, mesoscale angularity (adjusted by the gross shape of the organo-patch/branch) and small-scale surface roughness are introduced. As organo-patches continue to expand and connect (fb > 0.50; Fig. 1a(iii),(iv)), a well-developed polymeric network is established, embedding microbial cells, water and many sediment particles into aggregates. This network promotes increasingly complex morphologies at multiple scales, creating a ‘fluffy’ aggregate appearance (Fig. 1a(iii),(iv)).

To compare the drag acting on the amorphous and rough aggregates with that acting on smooth spheres, we quantified the differences in drag via the normalized drag ratio, \({C}_{\mathrm{D}}^{* }=\frac{{C}_{\mathrm{D}}}{{C}_{\mathrm{D0}}}\), where CD is the drag on the aggregates and \({C}_{{\mathrm{D0}}}=\frac{24}{\mathrm{Re}}(1+0.15{\mathrm{Re}}^{0.687})\) is the drag on volume-equivalent smooth spheres, following the widely acknowledged Schiller and Naumann’s drag law24. Our results show that the normalized drag ratios range between 1.0 and 4.0, indicating that the microbially colonized aggregates experience a 0–300% increase in drag compared with volume-equivalent spheres (Fig. 1b(i)–(iv)). In particular, the distribution curves of \({C}_{\mathrm{D}}^{* }\) shift towards higher values as microbial colonization intensifies (Fig. 1b(i)–(iv)). For poorly colonized aggregates (fb = 0–0.25), 82% of the aggregates experienced drag enhancements of less than 50%, with the remaining 18% having \({C}_{\mathrm{D}}^{* }\) values between 1.5 and 4.0 (Fig. 1b(i)). As microbial colonization intensified (fb = 0.25–0.75), a larger fraction (48% and 52%) of the aggregates experienced a drag enhancement of 50–300% (Fig. 1b(ii),(iii)). Aggregates in the well-developed state of microbial colonization (fb = 0.75–1.00) showed more pronounced drag enhancement, with 66% having 50–300% greater drag than the volume-equivalent smooth spheres (Fig. 1b(iv)). These results demonstrate that microbial colonization substantially increases drag on aggregates, with the effect becoming more pronounced as colonization intensifies.

Secondary peaks observed in Fig. 1b(ii),(iv) are probably attributable to variability in the sampling of microbial assemblages, sediment particle properties and local environmental conditions. These factors can produce diverse morphologies even under similar fb (Supplementary Fig. 1). Such structural variations shape the surrounding flow to different extents, contributing to secondary peaks in \({C}_{D}^{* }\). However, these secondary peaks represent a small fraction of the data and do not interrupt the overall trend of increasing proportions of aggregates with \({C}_{D}^{* } > 1.5\).

Influences of aggregate morphology on drag

Such substantial drag enhancements are not caused by the expansion in size associated with microbial colonization, as these effects are excluded by normalizing the drag with volume-equivalent spheres. Instead, the complex morphologies of microbially colonized aggregates play an important role in mediating drag on these aggregates. Here we explicitly investigated how aggregate morphology changes with microbial colonization and how these changes are connected to fluid drag variance.

To quantify the morphological complexities, we applied sphericity \((\delta =\frac{{A}_{\mathrm{o}}}{{A}_{\mathrm{p}}})\), as proposed by Wadell in 193225. This metric captures fine-scale morphology variance by calculating the surface area difference between volume-equivalent spheres (Ao) and irregular particles (Ap), where Ao represents the surface area of a sphere with the same volume as the particle, and Ap is the measured surface area of the particle itself. We directly calculated this 3D sphericity using high-resolution imaging of 3D aggregate structures at the microscale. Compared with conventional approximations that rely on measurements of representative diameters of aggregates (Supplementary Table 2)26, this approach enables fine-scale morphological variabilities to be more precisely captured (Supplementary Text 1 and Supplementary Fig. 2a–g).

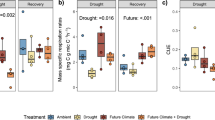

We observed a significant reduction in 3D sphericity as sediment aggregates become more heavily colonized by microorganisms and their metabolic products (Pearson correlation coefficient ρ = −0.841, P = 1.5 × 10−11; Fig. 2a). This trend highlights the capacity of microbial colonization to drive increasingly complex fine-scale morphology, probably through the production of metabolic products and formation of organo-colonies, patches and branches across the surfaces of sediment particles that frequently protrude into the water at different heights and angles.

a, 3D sphericity, which captures fine-scale morphological variance of the 3D aggregate structures (including small-scale surface roughness and mesoscale angularity of organo-patches and branches), shows a significant correlation with fb. b, Significant correlations between 3D sphericity and \({C}_{\mathrm{D}}^{* }\) for averaged data points within each δ range: 0–0.1 (n = 120), 0.1–0.2 (n = 714), 0.2–0.3 (n = 152), 0.3–0.4 (n = 338), 0.4–0.5 (n = 192), 0.5–0.6 (n = 102). P values in a and b are obtained from a Spearman correlation analysis (two-sided) (1.5 × 10−11, 0.005).

The observed increase in fine-scale morphological complexities, as indicated by the reduction in δ, significantly elevates the normalized drag coefficient (ρ = −0.649, P = 0.005, Fig. 2b). This finding implies that fine-scale morphology complexities created by microbial colonization substantially contribute to drag enhancement. Despite fluctuations in the distribution of the data points (explained in detail in Supplementary Text 2), these differences do not detract from the conclusion.

A morphology-corrected drag law

To quantify the morphological impacts on drag, we divided the microbially colonized sediment aggregates into six bins on the basis of their 3D sphericity (δ): 0–0.1; 0.1–0.2; 0.2–0.3; 0.3–0.4; 0.4–0.5; and 0.5–0.6 (Fig. 3a). For clarity, we present the results for the lowest (δ = 0–0.1), median (δ = 0.2–0.3) and highest (δ = 0.5–0.6) sphericity bins. Aggregates at each level of 3D sphericity display a relationship between fluid drag and the Reynolds number that varies with their 3D sphericity: aggregates with higher sphericity (δ = 0.5–0.6, dark blue dots and line in Fig. 3a) have a CD–Re relationship approximating that of smooth spheres (grey line in Fig. 3a), whereas those with lower 3D sphericity (δ = 0–0.1, yellow dots and line in Fig. 3a) notably deviate from that of a smooth sphere.

a, The relationship between CD and Reo varies with aggregate morphology (δ) and deviates from that of smooth spheres. The extent of deviation decreases with δ. Aggregates with higher sphericities (δ = 0.5–0.6, blue dots and line) have a CD–Re relationship closer to that of smooth spheres, whereas those with lower sphericities (δ = 0–0.1, yellow dots and line) have greater deviations. b, The scaling between Re′ and Reo also differs with δ. Normalizing the Re′ with Reo produces a significant relationship with δ, allowing Re′ to be calculated via the following formula: Re′/Reo = δa (where a = 0.32). Data in a–c are presented as mean values ± 1 s.d., and the shaded regions represent the 95% confidence intervals of the fitted curve. Means and error bars in a and b are derived from: n = 30, 15, 40, 17, 4, 6, 5, 3, 4, 3, 3, 13 (δ = 0.5–0.6); 42, 48, 39, 30, 9, 5, 4, 6, 3, 5 (δ = 0.2–0.3); and 37, 13, 28, 18, 9, 6, 5,4 (δ = 0.0–0.1) as Re increases. In c, n = 120 (δ = 0.0–0.1), 714 (δ = 0.1–0.2), 152 (δ = 0.2–0.3), 338 (δ = 0.3–0.4), 192 (δ = 0.4–0.5) and 102 (δ = 0.5–0.6). c, Integrating this effective Reynolds number into Schiller and Naumann’s drag law reconciles the differences across different morphological complexities and collapses the data into a single trend.

We introduced an effective Reynolds number (Re′) to represent the influence of the aggregate morphology on the local flow field. This factor was estimated by applying the CFD-simulated drag coefficient (CD) to Schiller and Naumann’s drag law24: \({C}_{\mathrm{D}}=\frac{24}{{\mathrm{Re}}^{\prime}}(1+0.15{\mathrm{Re}}^{{\prime}0.687})\). Normalizing the Re′ by the Reynolds number for volume-equivalent smooth spheres (Reo) shows significant correlations with the 3D sphericity (ρ = 0.912, P < 0.05). This trend is effectively described by Re′/Reo = δa, with a value of a = 0.32 (R2 = 0.71, Fig. 3b) calculated by taking the mean and standard deviation across different aggregate morphologies. As Re′/Reo and δ are two independent variables, with Re′/Reo derived from CFD simulations and δ derived from independent micro-CT measurements, this correlation confirms the critical role of fine-scale aggregate morphology in the alteration of the surrounding flow field.

Deviations (shown in Fig. 3b) occur due to aggregate rotation in the simulation and morphological differences with identical 3D sphericity. Aggregates with δ > 0.3 (less irregular and less well-colonized) fall slightly below the correlation line, whereas those with δ < 0.3 (more irregular and heavily colonized) tend to plot above it (Fig. 3b). This is because, as microbial colonization progresses, microbial substances (in addition to forming angular branches protruding into the water; Supplementary Fig. 1b), start to clog pores and smooth surface textures, forming smaller-scale features across aggregate–flow interfaces (Supplementary Fig. 1a1,2). These micro-sized protrusions exert a weaker influence on the flow field, moderating the rate of change in Re′/Reo with increasing 3D sphericity. However, this process does not disrupt the general trend of microbial colonization establishing increasingly complicated fine-scale morphologies and influences surrounding flow and drag. Importantly, as δ approximates 1 for smooth spheres, the morphology-corrected Reynolds number (Reoδa) converges to Reo, ensuring alignment with the original Schiller and Naumann’s drag law.

Plotting fluid drag against Reo • δa demonstrates that aggregates across different states of microbial colonization collapse into a single trend (Fig. 3c). This collapse confirms the significant correlations between Re′/Reo and δ (see Supplementary Text 2 for further analysis and Supplementary Fig. 3). This framework enables the drag differences introduced by various states of microbial colonization to be estimated through Reo • δa.

Our morphology-corrected drag law incorporates data from diverse sediment types, microorganisms, microbial colonization states and field sites, suggesting its potentially broad applicability in natural aquatic conditions. Integrating this law into sediment transport models, such as those for settling velocity estimates, reduces the root mean squared (r.m.s.) errors (Methods) from 466.4% to 85.7% (Supplementary Text 4 and Supplementary Fig. 4). These results highlight the critical role of fine-scale morphological complexities in reconciling the drag behaviour of suspended particles at varying states of microbial colonization. Incorporating these complexities, for example, by using the framework demonstrated in Fig. 3c, offers a pathway to improve accuracy in accounting for microbial influences on suspended sediment transport.

Sediment transport and biogeochemical implications

Our experiments uncover and quantify a hidden mechanism in microbially mediated sediment transport: microbial colonization enhances drag by complicating fine-scale morphology (Fig. 2a,b). This finding aligns with that of Deal et al.27, who suggested that fine-scale morphology increases drag on abiotic grains by a factor of 1–2, leading to the bed-load sediment flux varying by a factor of five or more. Microbial colonization amplifies such effects by generating more complex fine-scale morphology (Fig. 1a(i)–(iv)), resulting in greater drag increase (up to a factor of 3). This makes local maxima and minima of shear rates occur at the edges/protrusions of the irregular surfaces of microbial aggregates28, creating high drag heterogeneity on aggregate surfaces that contrasts starkly with the relatively homogeneous drag distribution of smooth shapes (Supplementary Fig. 5). Such complexities of fine-scale morphology and their impacts on drag cannot be captured by simply relying on gross shape descriptors or sphericity approximations (based on representative particle lengths) (Supplementary Figs. 6 and 7). This is further supported by the markedly different CD–Re relationships between structures with the same gross shape but distinct 3D sphericities (Supplementary Figs. 8 and 9).

Drag governs key processes of suspended sediment transport, including the settling velocity, the initiation of sediment suspension and suspended sediment fluxes. In our datasets, varying the morphology with δ in the range of 0.05–0.55 alters drag by a factor of 1.01–2.91. Neglecting these complexities, while simply focusing on microbial alteration of size and density, results in an overestimation of settling velocity by a factor of 1.00–1.71 (Supplementary Equation (1)) and critical resuspension thresholds by 1.01–2.91 (Supplementary Equation (2))29,30. This magnitude of variability for the same particle size and density underlines the scatter observed in situ and in laboratory settling column and flume experiments10,31,32,33. This overestimation is particularly important for heavily colonized aggregates, which are common in rivers, coastal estuaries and tidal flats4,8, where the critical shear stress for suspension can be overestimated threefold.

Although discrepancies remain between estimates and measurements, our morphology-corrected framework substantially improves prediction accuracy, reducing the r.m.s. errors for settling velocity from 466.4% to 85.7% (Supplementary Fig. 3). These remaining discrepancies stem partly from the flexibility of microbial substances, which exhibit viscoelastic behaviour that is not accounted for. During transport, microbial matrices may experience deformation and streamer oscillation, leading to energy dissipation and boundary layer disruption. This process contributes to additional drag enhancements of 0–30% and, in some cases, as much as 150–442% compared with rigid structures with equivalent morphological complexity34,35. In addition, 3D sphericity cannot capture every aspect of fine-scale morphological complexity, although it effectively characterizes the microbial-driven, fine-scale variability in morphology (Supplementary Table 2 and Supplementary Fig. 2). It should be noted that the scope of this study was not to define a definitive parameter for fine-scale morphology, but to demonstrate the critical role of fine-scale morphology in addressing key aspects of microbial sediment transport. Research in this context remains in its infancy, with critical gaps in measurement techniques, quantification methods and theoretical frameworks. Addressing these gaps will require sustained efforts to develop robust frameworks for conceptualizing morphological complexities and advancing observation techniques to reduce reliance on costly methods such as micro-CT imaging. Making these approaches more accessible and scalable will be crucial for further progress in this field.

Our findings imply that the predominant controls on sediment transport shift with the state of microbial colonization. For poorly colonized aggregates, where microbial effects are minimal, the microbial enhancement of drag is minor and easily counterbalanced by gravity due to size expansion. This makes size the predominant control, consistent with traditional models. However, as microbial colonization intensifies, intricate fine-scale morphologies amplify drag more substantially, exerting additional control over sediment transport, which in turn dilutes or even overrides the controlling role of size expansion and gravity9,33. This helps to explain the widely observed decoupling of settling velocities, bed stability and bedforms from size variance8,9,31. Consequently, neglecting fine-scale morphological dynamics in sediment transport models could introduce considerable errors4,27, which may become more pronounced in larger-scale and longer-term sediment transport processes, including sedimentation rates, sediment fluxes and morphodynamic evolution in estuaries, rivers and coastal systems. Fine-scale morphologies created by microbial colonization are also sensitive to environmental factors (nutrient status, temperature, acidification, dissolved oxygen and local hydrodynamics) and human activities28,33. By altering microbial activity and, consequently, fine-scale morphologies, these ongoing changes probably have greater impacts on sediment transport than we previously thought. Integrating fine-scale morphology dynamics into sediment transport models could help to predict how sediment transport and the related biogeochemical processes respond to environmental shifts and human activities across spatial and temporal scales more precisely.

Our findings also have profound implications for a variety of biogeochemical processes. Heavily colonized aggregates, which are often hotspots for organic matter accumulation, exert the most profound morphological influences on drag. Overlooking the morphological impacts while focusing solely on size can lead to overestimates of settling velocity and resuspension resistance, thereby underestimating their residence time and transport distance. This means that these carriers of organic matter might remain in the water longer than previously thought, affecting the attenuation of particulate organic carbon fluxes, remineralization depths and the overall efficiency of the biological carbon pump31,36,37. These aggregates also serve as key vehicles for nutrients and contaminants, making our findings critical for understanding benthic–pelagic exchanges, eutrophication38, harmful algae blooms39 and the source-to-sink processes of pollutants (such as microplastics and oil droplets)40,41,42. Given such common scenarios related to the transport of microbially colonized sediment, accounting for the morphological impacts and variances is essential. Future research should expand observations of fine-scale morphologies to diverse aggregate types (including marine snow, microplastic or oil-polluted aggregates and river and coastal mud), assess whether the effects of microbial colonization on morphology and drag observed within the current size range remain consistent across the full aggregate size spectrum and broaden such studies to diverse environmental conditions in other regions and processes.

Methods

Laboratory creation and field collection of aggregates

We investigated five types of microbially colonized sediment aggregate: two created in the laboratory (laboratory clay and sand aggregates) and three collected from the field (field muddy, silty and sandy aggregates). Laboratory clay and sand aggregates were generated through the resuspension of biosediments (as detailed by Zhang and colleagues10,23). In brief, biosediments were incubated from mixtures of fine-grained sand and microbial aggregates10,23. A plane bed of clean fine sand (d50 = 195 µm, range 125–250 μm) was overlaid with 15 cm of artificial seawater (Sigma sea salts, with a salinity of 35 psu) in a laboratory Core Mini Flume43. Microbial aggregates cultivated in advance with a single diatom species (Phaeodactylum tricornutum) and kaolinite clay23 were added and allowed to settle onto the sand substratum overnight. This mixture of sand and microbial aggregates underwent a 6-day cycle of daily resuspension (6 h) and deposition (18 h) to mimic hydrodynamic disturbances. During incubation, the mixtures were oxygenated and illuminated to support and promote the normal secretion of organic products. After incubation, resuspension experiments were performed following a standard protocol of applying stepwise increased motor-controlled shear stresses. The resuspension process involved two stages. During Stage 1 (with bed shear stresses ranging from 0.27–0.73 Pa), microbial clay aggregates (referred to as laboratory clay aggregates) were resuspended and collected. During Stage 2 (with bed shear stresses ranging from 0.73–1.09 Pa), microbial aggregates composed of sand grains (referred to as laboratory sand aggregates) were resuspended and collected.

Field samples were collected in November 2019 from two adjacent tidal flat sites in the Tay estuary, Scotland (56° 26′ 42″ N, 2°52′ 11″ W). One site was composed of sandy silt (silt:sand fraction = 47%, overall d50 = 60 µm and d50 of the sand fraction = 98 µm) and the other of silty sand (silt:sand fraction = 63%, overall d50 = 120 µm, d50 of the sand fraction = 239 µm). The field sediments from each site were mixed to homogenize the distributions of organic matter, remoulded into a plane bed in the Core Mini Flume and overlaid with 15 cm of artificial seawater (salinity of 35 psu). After settling overnight, resuspension experiments were conducted by applying stepwise increased motor-controlled shear stress, following the same protocols for laboratory aggregate creation. Field silty aggregates were collected at an applied shear stress of 0.46–0.80 Pa, and field sandy aggregates were collected at 1.09–1.69 Pa (ref. 10). In November 2018, field muddy aggregates were also collected via a 20 ml syringe from the fluff layer on the Hythe mudflat, south of Hythe town, and the western shore of Southampton Water, which is located on the southern coast of England44. The field muddy aggregates did not undergo laboratory reworking and were directly used for the micro-CT experiments.

Micro-CT experiments

A wet scanning method we developed previously was applied to characterize the internal structure and composition of the aggregates23. This method involves staining with alcohol and Alcian Blue dye (Sigma; 0.4 wt%/wt at pH 2.5). The scanning experiments for laboratory clay and field muddy aggregates were conducted using a Zeiss 160 kVp Versa 510 X-ray microscope. As for the other three types of aggregate, which contained larger sand grains and required a larger field of view, a modified 225 kVp Nikon HMX was used. Different vials were used for measurements to provide optimized scans in the two machines: a sealed 200 µl polypropylene pipette for the Versa and a transparent borosilicate nuclear magnetic resonance tube (Norel Standard Series; outer diameter, 4.9 mm; inner diameter, 4.2 mm; depth, 20 mm) for the HMX. Resolutions of 0.8 × 0.8 × 0.8 µm3 and 4.5 × 4.5 × 4.5 µm3 were achieved with the Versa and HMX, respectively. 3D microstructures (including the volumes, surface areas and volume-equivalent diameters of organic matter and sediment particles) and morphological complexities were quantified using a predeveloped protocol via CT-pro, ImageJ and Avizo 9.3.0 (refs. 45,46) (aggregate geometry characteristics obtained from micro-CT imaging are summarized in Supplementary Table 4)47,48.

CFD simulation of the flow field across 3D aggregates

The CFD simulation of aggregate settling was conducted using the open-source CFD library OpenFOAM. The CFD simulations in this study considered a flow regime with Re ranging from 0.1 to 100. This range is appropriate for aggregates with diameters of 50.38–508.40 µm, corresponding to flow velocities of 0.2 mm s−1 to 1.98 m s−1. These velocities encompass the settling velocities of the aggregates in this study (0.21–20.97 mm s−1), as well as those reported for biofilm–sediment aggregates by Shang et al.16 (7.48–40.24 mm s−1). Moreover, the critical shear velocities required to suspend these aggregates (17.61–32.40 mm s−1, obtained from previous flume experiments10) fall within this flow regime, ensuring that suspension dynamics are represented. These flow conditions are typical of natural environments, such as estuaries, tidal flats and extreme events like storms and floods49,50, emphasizing the relevance of this range to natural systems. Considering the relatively small Re range, Navier‒Stokes equations can be solved directly51,52, as defined in the following equations.

The continuity equation:

and the momentum equation:

Where u = (u, v, w) is the flow velocity vector, ρ is the fluid density, P is the pressure, ν is the kinematic viscosity and ∇u is the velocity gradient tensor. To account for the stochastic nature of aggregate transport direction, a Monte Carlo method was employed. This involves randomly rotating the aggregate geometry in a series of CFD simulations. The Semi-Implicit Method for Pressure Linked Equations algorithm was used to solve the governing equations. A second-order upwind scheme was applied to the advection terms, while a second-order central-difference scheme was used for diffusion terms.

In the CFD model, a rectangular computational domain is constructed to simulate aggregate settling (Supplementary Fig. 10a). This domain is designed with specific boundary conditions: the inlet and outlet are situated at the upstream and downstream boundaries, while free-shear boundary conditions are applied to the sides. The aggregate is positioned at the centre of the domain, ensuring a minimum distance of ten times its diameter (10dp) from all computational boundaries to avoid boundary effects on flow behaviour. Downstream, the computational boundary is extended to a distance of twenty diameters (20dp) to allow adequate wake development. Free-shear boundary conditions were applied to the side boundaries.

To capture the complex flow dynamics around the aggregate, a body-fitted mesh was generated using OpenFOAM’s snappyHexMesh utility. This mesh was gradually refined near the aggregate surface to resolve geometric features and boundary layers effectively (Supplementary Fig. 10b). The mesh design was validated through a convergence study, which demonstrated that both the size of the computational domain and the mesh refinement level considerably influence the drag coefficient accuracy. For example, smaller computational domains, such as 5dp, constrained wake development and produced less reliable drag predictions (Supplementary Fig. 10a). In contrast, larger domains improved wake resolution but demanded more computational resources. We found that a domain size of 10dp, with a mesh refinement level of Nr = 4 (corresponding to 8,652,944 cells), provided the best balance between computational accuracy and cost (Supplementary Fig. 11a). This set-up reliably captured the flow structure around the particle, as demonstrated by the agreement of the computed drag coefficients with the Schiller and Naumann’s correlation across a range of particle Re (Supplementary Fig. 11b).

The drag force acting on the aggregate was computed by integrating stress over its the 3D aggregate structure47. Mathematically, this is expressed as:

Where p is pressure, n is the unit normal vector on the aggregate structure, μ is the dynamic viscosity and dS represents an infinitesimal surface area element. The simulation achieved convergence when the drag force stabilized with a relative difference below 0.1% and the scaled residuals of all state variables fell below 1 × 10−5.

Statistical analysis

We performed statistical analyses in IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows (Version 29.0). Correlation analysis was conducted using Pearson’s correlation coefficient (ρ) to measure the strength and direction of linear relationships between variables. Two-tailed significance tests were performed to determine statistical significance. This analysis provided insights into the relationships between key variables. The r.m.s. error \(\sqrt{\frac{1}{n}\mathop{\sum }\nolimits_{i=1}^{n}{\left(\;{y}_{i}-\hat{{y}_{i}}\right)}^{2}}\times 100 \%\), was applied to demonstrate the prediction accuracy, where yi and \(\hat{{y}_{i}}\) are predicted and observed data53.

Data availability

The CFD data that support the findings of this study are publicly available via figshare at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.28179983 (ref. 47), and examples of 3D aggregate structures are available at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.28481231 (ref. 48). Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

All simulations were conducted using the open-source CFD toolbox OpenFOAM (v2202). The source code of OpenFOAM is publicly available at https://www.openfoam.com/.

Change history

27 May 2025

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41561-025-01723-2

References

Flemming, H. C. & Wingender, J. The biofilm matrix. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 8, 623–633 (2010).

Flemming, H.-C. & Wuertz, S. Bacteria and archaea on Earth and their abundance in biofilms. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 17, 247–260 (2019).

Harris, B. S. et al. Biostabilization: parameterizing the interactions between microorganisms and siliciclastic marine sediments. Earth Sci. Rev. 259, 104976 (2024).

Maerz, J., Six, K. D., Stemmler, I., Ahmerkamp, S. & Ilyina, T. Microstructure and composition of marine aggregates as co-determinants for vertical particulate organic carbon transfer in the global ocean. Biogeosciences 17, 1765–1803 (2020).

Passow, U. Formation of rapidly-sinking, oil-associated marine snow. Deep Sea Res. Pt 2 129, 232–240 (2016).

Lamb, M. P. et al. Mud in rivers transported as flocculated and suspended bed material. Nat. Geosci. 13, 566–570 (2020).

Alldredge, A. The carbon, nitrogen and mass content of marine snow as a function of aggregate size. Deep Sea Res. Pt I 45, 529–541 (1998).

Maggi, F. & Tang, F. H. M. Analysis of the effect of organic matter content on the architecture and sinking of sediment aggregates. Mar. Geol. 363, 102–111 (2015).

Iversen, M. H. & Lampitt, R. S. Size does not matter after all: no evidence for a size-sinking relationship for marine snow. Prog. Oceanogr. 189, 102445 (2020).

Zhang, N., Thompson, C. E. L. & Townend, I. H. The effects of disturbance on the microbial mediation of sediment stability. Limnol. Oceanogr. 68, 1567–1579 (2023).

Mariotti, G., Pruss, S. B., Perron, J. T. & Bosak, T. Microbial shaping of sedimentary wrinkle structures. Nat. Geosci. 7, 736–740 (2014).

Malarkey, J. et al. The pervasive role of biological cohesion in bedform development. Nat. Commun. 6, 6257 (2015).

Khelifa, A. & Hill, P. S. Models for effective density and settling velocity of flocs. J. Hydraul. Res. 44, 390–401 (2006).

Fang, H., Shang, Q., Chen, M. & He, G. Changes in the critical erosion velocity for sediment colonized by biofilm. Sedimentology 61, 648–659 (2014).

Fang, H., Cheng, W., Fazeli, M. & Dey, S. Bedforms and flow resistance of cohesive beds with and without biofilm coating. J. Hydraul. Eng. 143, 06017010 (2017).

Shang, Q. Q., Fang, H. W., Zhao, H. M., He, G. J. & Cui, Z. H. Biofilm effects on size gradation, drag coefficient and settling velocity of sediment particles. Int. J. Sediment Res. 29, 471–480 (2014).

Andalib, M., Zhu, J. & Nakhla, G. Terminal settling velocity and drag coefficient of biofilm‐coated particles at high Reynolds numbers. AlChE J. 56, 2598–2606 (2010).

Kabir, A. M. R. et al. Drag force on micron-sized objects with different surface morphologies in a flow with a small Reynolds number. Polym. J. 47, 564–570 (2015).

Riazi, A. & Türker, U. The drag coefficient and settling velocity of natural sediment particles. Comput. Part. Mech. 6, 427–437 (2019).

Ro, K. S. & Neethling, J. B. Terminal settling characteristics of bioparticles. Res. J. Water Pollut. Contr. Fed. 62, 901–906 (1990).

Saravanan, V. & Sreekrishnan, T. R. Hydrodynamic study of biogranules obtained from an anaerobic hybrid reactor. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 91, 715–721 (2005).

Paterson, D. M. Biogenic structure of early sediment fabric visualized by low-temperature scanning electron microscopy. J. Geol. Soc. London 152, 131–140 (1995).

Zhang, N. et al. Nondestructive 3D imaging and quantification of hydrated biofilm-sediment aggregates using X-ray microcomputed tomography. Environ. Sci. Technol. 52, 13306–13313 (2018).

Clift, R. & Gauvin, W. H. Motion of entrained particles in gas streams. Can. J. Chem. Eng. 49, 439–448 (1971).

Wadell, H. Volume, shape, and roundness of rock particles. J. Geol. 40, 443–451 (1932).

Rorato, R., Arroyo, M., Andò, E. & Gens, A. Sphericity measures of sand grains. Eng. Geol. 254, 43–53 (2019).

Deal, E. et al. Grain shape effects in bed load sediment transport. Nature 613, 298–302 (2023).

Zetsche, E. M., Larsson, A. I., Iversen, M. H. & Ploug, H. Flow and diffusion around and within diatom aggregates: effects of aggregate composition and shape. Limnol. Oceanogr. 65, 1818–1833 (2020).

Bagnold, R. A. An Approach to the Sediment Transport Problem from General Physics (US Government Printing Office, 1966).

Van Rijn, L. C. Principles of Sediment Transport in Rivers, Estuaries and Coastal Seas (Aqua, 1993).

Cael, B. B., Cavan, E. L. & Britten, G. L. Reconciling the size‐dependence of marine particle sinking speed. Geophys. Res. Lett. 48, e2020GL091771 (2021).

Amos, C. L. et al. The stability of tidal flats in Venice Lagoon - the results of in-situ measurements using two benthic, annular flumes. J. Mar. Syst. 51, 211–241 (2004).

Laurenceau-Cornec, E. C., Trull, T. W., Davies, D. M., De La Rocha, C. L. & Blain, S. Phytoplankton morphology controls on marine snow sinking velocity. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 520, 35–56 (2015).

Snowdon, A. A., Dennington, S. P., Longyear, J. E., Wharton, J. A. & Stoodley, P. Surface properties influence marine biofilm rheology, with implications for ship drag. Soft Matter 19, 3675–3687 (2023).

Stoodley, P., Lewandowski, Z., Boyle, J. D. & Lappin-Scott, H. M. Oscillation characteristics of biofilm streamers in turbulent flowing water as related to drag and pressure drop. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 57, 536–544 (1998).

Kwon, E. Y., Primeau, F. & Sarmiento, J. L. The impact of remineralization depth on the air–sea carbon balance. Nat. Geosci. 2, 630–635 (2009).

Battin, T. J. et al. Biophysical controls on organic carbon fluxes in fluvial networks. Nat. Geosci. 1, 95–100 (2008).

Jago, C. F., Kennaway, G. M., Novarino, G. & Jones, S. E. Size and settling velocity of suspended flocs during a Phaeocystis bloom in the tidally stirred Irish Sea, NW European shelf. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 345, 51–62 (2007).

Ralston, D. K., Brosnahan, M. L., Fox, S. E., Lee, K. D. & Anderson, D. M. Temperature and residence time controls on an estuarine harmful algal bloom: modeling hydrodynamics and Alexandrium fundyense in Nauset estuary. Estuar. Coasts 38, 2240–2258 (2015).

Long, M. et al. Interactions between microplastics and phytoplankton aggregates: impact on their respective fates. Mar. Chem. 175, 39–46 (2015).

Porter, A., Lyons, B. P., Galloway, T. S. & Lewis, C. Role of marine snows in microplastic fate and bioavailability. Environ. Sci. Technol. 52, 7111–7119 (2018).

Arnosti, C., Ziervogel, K., Yang, T. & Teske, A. Oil-derived marine aggregates - hot spots of polysaccharide degradation by specialized bacterial communities. Deep Sea Res. Pt 2 129, 179–186 (2016).

Thompson, C. E. L., Couceiro, F., Fones, G. R. & Amos, C. L. Shipboard measurements of sediment stability using a small annular flume—Core Mini Flume (CMF). Limnol. Oceanogr. Methods 11, 604–615 (2013).

Stead, J. The Fate and Transport of Microplastics Within Estuaries. University of Southampton, PhD thesis (2022).

Callow, B., Falcon-Suarez, I., Ahmed, S. & Matter, J. Assessing the carbon sequestration potential of basalt using X-ray micro-CT and rock mechanics. Int. J. Greenh. Gas Contr. 70, 146–156 (2018).

Wheatland, J. A. T., Bushby, A. J. & Spencer, K. L. Quantifying the structure and composition of flocculated suspended particulate matter using focused ion beam nanotomography. Environ. Sci. Technol. 51, 8917–8925 (2017).

Zhang, N. Microbial effects on drag in suspended sediment. figshare https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.28179983 (2025).

Zhang, N. 3D structures of sediment aggregates at different states of microbial colonization. figshare https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.28481231 (2025).

Jiang, J. et al. Mechanism of rapid accretion-erosion transition in a complex hydrodynamic environment based on refined in-situ data. Front. Mar. Sci. 11, 1375085 (2024).

Wu, X., Xie, W., Zhang, N., Guo, L. & He, Q. Different response of hydrodynamics and near-bottom sediment transport to a cold front in the Changjiang Estuary and its submerged delta. J. Mar. Syst. 247, 104022 (2025).

Li, H. & Sansalone, J. CFD as a complementary tool to benchmark physical testing of PM separation by unit operations. J. Environ. Eng. 146, 04020122 (2020).

Li, H. & Sansalone, J. CFD model of PM sedimentation and resuspension in urban water clarification. J. Environ. Eng. 146, 04019118 (2020).

Hodson, T. O. Root-mean-square error (RMSE) or mean absolute error (MAE): when to use them or not. Geosci. Model Dev. 15, 5481–5487 (2022).

Acknowledgements

This research was sponsored by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant numbers 42206059 (awarded to N.Z.), 42376168 (awarded to F.X.) and U2040216 (awarded to Q.H.)), and the National Key 507 Research and Development Program of China (grant numbers 2024YFE0103100 and 2022YFA1004401 awarded to F.X.) and the AI Tennessee Initiative and UT-Oak Ridge Innovation Institute at the University of Tennessee. We thank D. Paterson and A. Blight of St Andrews University for hosting field sampling work in Scotland, K. Rankin and O. Katsamenis for their assistance in performing the scans carried out at the μ-VIS X-ray Imaging Centre, University of Southampton and J. Shen from the Virginia Institute of Marine Science for discussions on the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

N.Z. conceived the study. N.Z. and F.X. performed data analysis, developed the theory and wrote the manuscript with input from H.L., C.E.L.T., I.H.T. and Q.H. C.E.L.T. and I.H.T. supervised the laboratory experiments and field observations for the microbially mediated sediment transport. N.Z. collected the samples and ran laboratory incubation, flume and micro-CT imaging experiments. H.L. conducted the CFD simulations of drag acting on aggregate structures. Q.H. supervised the project.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Geoscience thanks Thomas Lawrence and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editor: Tamara Goldin, in collaboration with the Nature Geoscience team.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Texts 1–3, Equations (1) and (2), Figs. 1–9, Tables 1–3 and References.

Supplementary Data 1

Source data for Supplementary Figs. 3, 4, 8 and 9.

Source data

Source Data Fig. 1

Frequency distribution of the normalized drag coefficient and its variance with microbial colonization states.

Source Data Fig. 2

The relationships between microbial colonization states, aggregate morphology and the induced drag variance.

Source Data Fig. 3

Cd–Re relationship variance with aggregate morphology.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, N., Li, H., Xu, F. et al. Drag acting on suspended sediment increased by microbial colonization. Nat. Geosci. 18, 396–401 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41561-025-01679-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41561-025-01679-3

This article is cited by

-

Minerals provide divergent protection to carbon- and nitrogen-rich organic matter in fluvial sediments

Communications Earth & Environment (2025)

-

Fabrication of Functional Biobased Epoxy Coatings via Cinnamic Acid Grafting: Synergistic Antibacterial, Antifouling, UV-resistant, and Superhydrophobic Properties

Chinese Journal of Polymer Science (2025)