Abstract

The development of life on Earth has been enabled by its volatile-rich surface. The volatile budget of Earth’s surface is controlled by the balance between ingassing (for example, via subduction) and outgassing (for example, through magmatic and tectonic processes). Although volatiles within Earth’s interior are relatively depleted compared to CI chondrites, the total amount of volatiles within Earth is still substantial due to its vast size. However, the relative extent of diffuse degassing from Earth’s interior, not directly related to volcanism, is not well constrained. Here we use dissolved helium and high-precision argon isotopes combined with radiocarbon of dissolved inorganic carbon in groundwater from the Columbia Plateau Regional Aquifer (Washington and Idaho, USA). We identify mantle and crustal volatile sources and quantify their fluxes to the surface. Excess helium and argon in the groundwater indicate a mixture of sub-continental lithospheric mantle and crustal sources, suggesting that passive degassing of the sub-continental lithospheric mantle may be an important, yet previously unrecognized, outgassing process. This finding that considerable outgassing may occur even in volcanically quiescent parts of the crust is essential for quantifying the long-term global volatile mass balance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

While volcanic degassing has canonically been considered the primary source of outgassing from our planet’s interior, recent studies have challenged this1. In particular the sub-continental lithospheric mantle (SCLM), which, while only comprising ~2.5% of the total mantle2, may provide a considerable juncture for devolatilization due to its adjacency to crustal settings. However, to date, this prospective outgassing pathway remains uncertain. Typically, continental volatile fluxes have been determined by the measurement of He isotopes in groundwater and springs3,4,5,6,7. However, there is often ambiguity in attributing volatile signals to sources because 4He is produced (from U and Th decay) within aquifers, in the deeper crust and in the mantle3,4,8. Additionally, different mantle sources have distinct 3He/4He compositions, which complicates the identification and quantification of mantle He inputs (for example, refs. 8,9,10,11,12). Argon-40, a radiogenic nuclide and the third most abundant constituent of the atmosphere, is a promising complementary tracer to He isotopes for the outgassing of other volatiles due to its inert nature and continual production (via K decay) within the mantle and crust13,14,15.

The majority of groundwater within the upper kilometre of the crust has a sufficiently long residence time (that is, the average amount of time since a parcel of water has been isolated from the atmosphere) to represent a useful archive of hydrogeologic processes and volatile fluxes16,17. Determination of excess (that is, non-atmospheric) dissolved He and Ar in aquifers offers the potential to provide insights into the transfers of volatiles between deep Earth and the surface. However, analytical limitations have largely precluded detection of excess 40Ar (40Ar*) in order ten thousand-year-old (ka) groundwater, due to the large atmospheric contribution. Deep radiogenic 4He and 40Ar fluxes have previously been observed in several ancient (>100 ka) waters from deep mines and artesian systems, where 40Ar/36Ar has been observed to exceed atmospheric ratios at the percent scale14,18,19. Recent developments for the analysis of heavy noble gas isotopes at sub-per-mille precision20,21 provides the quantitative resolution for robustly determining 40Ar* in younger groundwater through the ‘triple Ar isotope’ approach. This method uses the non-radiogenic Ar isotopes (38Ar and 36Ar) to disentangle atmospheric 40Ar from low-level geological input from the radioactive decay of K in the solid Earth22,23.

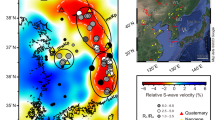

Here we report measurements of triple-argon isotopes and He isotopes (n = 33 and n = 21, respectively) in groundwater from 17 wells, alongside noble gas abundances and radiocarbon activity of dissolved inorganic carbon (DIC)24 (Extended Data Fig. 1), to determine deep volatile sources and fluxes to the Palouse Basin Aquifer (PBA). Physiochemical parameters and associated well depths can be found in Extended Data Table 1. The PBA is a fractured-rock and interbedded sediment aquifer system that supplies municipal water to regional communities as part of the Columbia Plateau Regional Aquifer (CPRA). This CPRA comprises several units of the Columbia River Basalt Group (CRBG) that probably formed as a result of the Yellowstone hotspot (Methods). Previous work within the study area has suggested the presence of mantle carbon input to deep groundwater25, however the origin, migration pathway and timing of this inferred mantle input is unknown. This investigation integrates He isotope, radiocarbon and high-precision triple-argon-isotope measurements and proposes a multi-tracer approach towards utilizing palaeogroundwater as a record of volatile input from deep crustal and mantle sources to Earth’s surface. The addition of the 40Ar tracer alongside helium isotopes allows for both a mantle contribution and the source of this contribution (for example, in situ vs ex situ) to be identified, which was not previously possible with the helium isotope alone, as the intermediate 3He/4He are between various mantle endmembers and the crust (Fig. 1), complicating any attempts to evaluate the mantle source.

Symbol colours correspond to the Δ40Ar excess (excess readiogenic 40Ar relative to atmospheric air) observed within the samples (n = 17), errors are measured value ±1σ uncertainties and are within the symbol size. The grey line represents mixing between ASW and crust (0.02 to 0.1 RA (refs. 30,31)). The yellow lines represents mixing between ASW and mantle (SCLM 6.1 ± 2.1 RA (ref. 9, where RA is atmospheric ratio), MORB 8 ± 1 RA (ref. 8) and deep mantle plume source 16–22 RA (refs. 10,11,12)) (dashed lines). Four samples (Moscow 2, Moscow 3, Elk Golf and Parker Farm) are consistent with a purely crustal line; these samples also have no Δ40Ar excess and are referred to as the ‘crustal samples’.

Noble gas excesses in groundwater

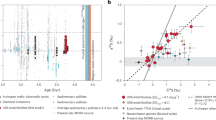

Radiocarbon activities (of DIC) are between 3.5 and 52.0 percent modern carbon (pmC), corresponding to apparent groundwater residence times between ~27,000 and ~9,000 years. These ages are in agreement with previous studies in the area25,26—although the oldest 14C ages may exhibit small biases (order 1 ka) due to 14C-free mantle carbon input (Extended Data Fig. 2 and Methods). Concentrations of Ne, Ar, Kr and Xe are in agreement with predictions from the expected noble gas concentrations in groundwater due to equilibrium gas exchange and excess air dissolution (closed equilibrium (CE) model, see ref. 27) at 800 m surface elevation (0.91 atm) with temperatures between 4.7 and 8.1 °C (ref. 24) and an excess air component. However, He concentrations vary by nearly two orders of magnitude from 0.08 to 4.44 × 10−6 cm3STP gw−1, where STP is standard temperature and pressure and w is water (Extended Data Tables 2 and 3). Similarly, measured 3He/4He (R), reported as R/RA relative to the atmospheric ratio (RA), range between 0.24 and 3.37 RA. Surprisingly, both the highest 4He concentrations and the highest 3He/4He are observed in the deepest (oldest) samples, suggesting that deep volatile sources contribute mantle and radiogenic He to the aquifer. This result is remarkable, because, outside of a direct volcanic setting, the conventional expectation is for groundwater to inherit crustal 4He from radioactive decay of U and Th in aquifer minerals, leading to a lowering of 3He/4He with increasing 4He.

Helium in groundwater is derived from a combination of atmospheric, mantle and crustal sources. Combining 3He/4He with 4He/Ne is a useful approach to identify and distinguish distinct He sources28,29, because, unlike 4He, Ne only has an appreciable atmospheric source. In the PBA, there is a considerable mantle He contribution in groundwater from 13 of the 17 wells (Fig. 1). The remaining four wells (Elk Golf, Parker Farm, Moscow 2 and Moscow 3) have excess helium (that is, 4He/Ne above air-saturated water (ASW)) but have no discernible mantle contribution, as they lie along a mixing curve between ASW and a pure crustal endmember (3He/4He ~ 0.1 RA (refs. 30,31)). These four dominantly crustal samples (hereafter, ‘crustal samples’) have the youngest radiocarbon ages (<10,000 years) and the warmest recharge temperatures (>7 °C) (refs. 24). These crustal samples were collected from shallow wells (<175 m) in the east of the study area (Extended Data Fig. 1), where recent, local recharge is known to occur26,32 resulting in no discernible deep mantle flux in these samples. Samples with the highest 3He/4He—indicative of the greatest mantle contributions—are from the deep wells in the western part of the study area (Methods).

To quantify He excesses (3Hexs and 4Hexs) in groundwater, atmosphere-derived He (that is, the component from air–water equilibration and excess air determined using the CE model) is subtracted from measured 3He and 4He concentrations (Methods). Modelled atmospheric (CE model) He isotope concentrations can be found in ref. 24. Excess 4He concentrations vary between 0.02 and 4.38 × 10−6 cm3STP gw−1 and correlate with 3Hexs, which is up to 1.09 ± 0.01 × 10−11 cm3STP gw−1.

The excess radiogenic Ar can also be investigated relative to atmospheric air (Δ40Ar) in per mille (Methods and Extended Data Figs. 3 and 4). While the highest Δ40Ar values were identified in the oldest samples (that is, samples with the lowest radiocarbon activities), the four dominantly crustal samples (Fig. 1) do not exhibit any discernible 40Ar*. Notably, the highest measured radiogenic 40Ar excess (Δ40Ar = 3.18 ± 0.02‰; 40Ar* = 1.36 × 10−6 ± 0.01 cm3STP gw−1) would not be discernible from air or ASW at the precision of static noble gas mass spectrometry (that is, ~5‰ vs ~0.01‰ for dynamic mass spectrometry), highlighting the importance of this new technique to expand the application of radiogenic Ar isotope analyses to a wider range of natural samples.

We observe a striking correlation between 4Hexs (measured via static mass spectrometry) and 40Ar* (measured via dynamic mass spectrometry) (Fig. 2; r2 = 0.92), indicating that their accumulations are related. Surprisingly, an even stronger correlation (r2 = 0.99) exists between 3Heex and 40Ar*. Excess 3He is predominately derived from the mantle, and its production within the PBA33 and from the decay of tritium should be negligible (Methods), therefore this high correlation may indicate that a substantial portion of 40Ar* may also derive form the mantle. We note that per-mille-scale Δ40Ar anomalies were also previously measured in ~10,000-year-old groundwater in Southern California, in the first application of this new technique23. At the time, it was speculated that weathering of aquifer minerals represented the likely 40Ar release mechanism into groundwater. However, the unexpectedly strong correlation between 3He and 40Ar observed here (and the lack of He isotope measurements in the previous study) raises the possibility that elevated 40Ar* identified in Southern California groundwater may likewise reflect an input of mantle-derived volatiles, perhaps in relation to the nearby San Andreas fault7. Similarly, in the Tucson Basin, where 3He measurements indicate no mantle contribution, 40Ar* was consistently found to be zero (within error) in groundwaters (up to 30,000 years) (ref. 20). The lack of excess 40Ar in a system without mantle input further hints at the mantle playing a potentially dominant role in the flux of 40Ar to shallow groundwater. Diffusive degassing of mantle volatiles has important implications for the use of radiogenic volatiles as groundwater residence time tracers, as 4He is a common groundwater dating tool. Thus, the notion that 40Ar (like 3He and 4He) has a mantle source in some shallow groundwater settings raises the possibility that 40Ar may offer additional constraints to refine and improve 4He dating.

a,b, Relationship between 4Hexs (a) and 3Hexs (b) and concentrations relative to 40Ar* in the Palouse Basin Aquifer samples (n = 17). Symbol sizes are larger than the measured excess ±1σ uncertainties. Unfilled = samples with only crustal noble gas addition from in situ production. Dashed lines represent the line of best fit through the samples with the external excesses (filled) and the r2 value for each is shown in the bottom right corner (note: unfilled ‘in situ only’ samples were not used in calculating the correlation).

In this study, our focus is on the origin of deep volatiles, and we dedicate the following analysis to better understand (1) how mantle-derived 40Ar infiltrates aquifers and (2) how important this mantle flux may be within the framework of the global volatile cycle.

Origin of gases in the Columbia Plateau regional aquifer

The observation of substantial 4Hexs, 3Hexs and 40Ar* in PBA groundwater, which are all correlated, suggests a co-genetic relationship between the geological sources of noble gases within the system. 4Hexs and 40Ar* could accumulate either because of (1) in situ production from the decay of U, Th and K decay in the aquifer minerals and subsequent release into the groundwater via diffusion and/or mineral dissolution or (2) an external, deeper flux from a crustal and/or mantle source. The presence of mantle-derived 3He within the aquifer suggests a mantle-derived volatile flux into the system.

Here we determine the amount of external He input (3Heext and 4Heext) from deep crustal and mantle sources, below the PBA, by subtracting in situ He isotope production from 3Hexs and 4Hexs (Methods). Assuming that the crustal dominated samples have no external contributions, these concentrations can be used to generate conservative estimates of 3Heext and 4Heext to be between 1.6 and 10.8 × 10−12 cm3STP gw−1 and between 0.61 and 4.05 × 10−6 cm3STP gw−1, respectively. Assuming that all 4Hexs in these samples is derived from in situ production, the in situ accumulation rate of 4He (and 3He) in each sample can be calculated from 4Hexs concentrations, radiocarbon ages and a crustal production endmember of 0.1 Ra. The average in situ accumulation rate for the crustal samples is 1.49 × 10−11 cm3STP gw−1 yr−1, similar to previous estimates of in situ 4He production within the CRBGs (1.7 × 10−11 cm3STP gw−1 yr−1 (ref. 34)). In the 13 mantle-influenced wells, we then apply these estimated in situ accumulation rates and, using the radiocarbon ages, we quantify the amounts of excess 4He and 3He that has resulted from in situ production, using a Monte Carlo approach to propagate uncertainties (Methods).

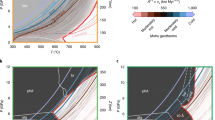

In principle, we can similarly quantify the in situ production and accumulation of 40Ar to estimate external 40Ar (40Arext). While it is conventionally assumed that all He produced within aquifer minerals readily diffuses into groundwater (that is, release factor ~ 1; ref. 30), the limited work on 40Ar* in groundwater suggests that low-temperature diffusive release of 40Ar* from a mineral is much slower than He, owing to the larger atomic radius of Ar14,23,33. To estimate the maximum amount of 40Ar* from in situ production within the PBA, we follow the methods of ref. 35 (Methods), assuming a maximum K concentration of 2.3 wt% (ref. 36). We then model in situ 40Ar* production across a wide range of release factors (from 0 to 1 (ref. 37), given the lack of deformation and stability in the PBA) and across the published range of porosity values in the CPRA (from 0.08 to 0.3 (ref. 36)). We find that even with a release of 1 (that is, 100% release) and a minimum porosity of 0.08, the maximum amount of 40Ar* that can accumulate over ~20,000 years (~5.5 × 108 cm3STP gw−1) represents, at most, only 4% of the highest 40Ar* observed in this study (1.36 × 10−6 cm3STP−1 gw−1) (Fig. 3). Adopting the most plausible parameters (for example, a release factor <<1 (ref. 14) and a median porosity of ~0.2), the vast majority of 40Ar* in all samples must be derived from an external source, with only negligible input of 40Ar to the aquifer from in situ production within the CPRA minerals (that is, 40Arext ≈ 40Ar*).

40Ar* concentrations are modelled for varying release factors (0–1) and porosities (0.08–0.3 (ref. 35)). White lines and numbers represent the contours of 40Ar* concentration (× 10−8 cm3STP gw−1) output from the model. Expected 40Ar* concentration is calculated following the methods in ref. 35. The maximum concentration of 40Ar* produced in situ is ~5.5 × 10−8 cm3STP gw−1.

Understanding the source of this external flux is important for quantifying global volatile fluxes from diffuse degassing, and aquifers represent an excellent tool to constrain the flux. The highest observed (3He/4He)ext of 4.0 ± 1.4 RA coincides with a (4He/40Ar)ext of ~1.6 (Fig. 4), both of which fall within the ranges of values characteristic of the SCLM (that is, 6.1 ± 2.1 RA (ref. 9) and 1–3 (ref. 8), respectively), suggesting that the SCLM is the main volatile source. It is however possible that these values could be a co-incidental mix of a higher mid-ocean-ridge basalt (MORB)/plume endmember and the deep continental crust. To further distinguish between mantle volatile sources, we constructed a mixing model using the calculated externally derived concentrations of He and Ar isotopes (3Heext, 4Heext and 40Ar*) and assuming all 40Ar* is externally sourced (as discussed above) (Fig. 4 and Extended Data Fig. 5). Our data closely plot along a mixing curve between a high 3He/4Heext and low 4He/40Ar* endmember (mantle derived) and a low 3He/4Heext and high 4He/40Ar* endmember (crustal derived). We adopt a Monte Carlo least squares fitting approach to determine the composition of the crustal and mantle endmembers (Methods). We find that a high crustal 4He/40Ar endmember (>100) is required, suggesting that the crust-derived 4He/40Ar in the system has been highly fractionated (that is, enriched in 4He) compared to typical crustal 4He/40Ar production ratios (~4 (refs. 15,18,30)). We suggest that the inferred high 4He/40Ar endmember reflects the preferential release of 4He relative to 40Ar* from a deeper crustal source, due to the higher release temperature of Ar from minerals30. Notably, similar fractionation in the 4He/40Ar* (>100) has been observed in other groundwater studies worldwide13,38. The same fractionation is not expected within the mantle endmember, due to the higher temperatures allowing for quantitative release of both 4He and 40Ar*, unlike the crustal source.

3He/4Heext vs 4He/40Ar*ext from the mantle-influenced samples (n = 13) is used to model the expected mixing between mantle and crustal endmembers (grey line). The black square represents the most likely mantle composition (SCLM) based on a 4He/40Ar* within the mantle range (2 ± 1 (ref. 8)). Tick marks represent a 75%, 50% and 25% mantle contribution. The crustal 4He/40Ar* is probably highly fractionated, but changing this value only has minimal effect on the mantle endmember composition. Symbol colours represent the 40Ar* concentration within the samples and external values ± 1σ uncertainties are shown. The four dominantly crustal samples high the highest 4He/40Ar*ext and lowest 3He/4Heext.

Our Monte Carlo mixing model approach enables estimation of the mantle source 3He/4He by adopting an assumed mantle 4He/40Ar of 1 (that is, the lowest end of the canonical range8) and evaluating the mixing curve at this value after fully propagating uncertainties in both 3He/4Heext and 4He/40Arext (Methods). This yields an implied mantle source 3He/4He of 5.5 ± 0.4 RA, consistent with the He isotope composition of the SCLM9, but statistically incongruent with either a MORB or plume-like mantle helium source. We note the mantle 4He/40Ar* of the mantle endmember may be fractionated by degassing or during transport (Methods). Although there are two possible minor tectonic faults with minimal offset within the study region (Extended Data Fig. 1), the basin is considered stable and lacks deformation39,40,41, and as a result, we do not expect much influence from movement along faults within the PBA. We suggest that the conceptually most straightforward and likely source of mantle-derived volatiles to the PBA is diffusive degassing of the SCLM. Furthermore, the setting of the PBA, far inland from the Cascadia subduction zone and distal (>500 km) from the current location of the Yellowstone hotspot with no thermal evidence of mantle upwelling42 (Methods), further supports the suggestion of a SCLM source.

Implications for global volatile fluxes

The findings of this multi-tracer study suggest that passive 40Ar (and He) degassing from the SCLM through shallow groundwaters may represent a broader, yet underappreciated, mechanism for large-scale degassing of related mantle volatiles including CO2, nitrogen and sulfur43,44 to the upper crust and atmosphere. This work demonstrates a previously hidden volatile flux from the mantle that can accumulate appreciably, even in relatively young groundwater systems. The results of this study imply that the contribution of passive mantle outgassing to the global volatile balance may be more prevalent than previously considered. For example, understanding mantle and crustal fluxes has important implications for models of mantle and crustal outgassing and for long-term and large-scale geochemical evolution of the major terrestrial reservoirs (for example, atmosphere and mantle)22,45,46.

Future measurements made possible by the triple-argon-isotope approach will enable investigation of mantle 40Ar fluxes to groundwater on a broader scale. The recognition that diffuse volatile degassing from the SCLM through continental aquifers may be more ubiquitous than originally hypothesized22,47,48. Our findings of mantle He and Ar input into the shallow crustal settings reveals that evidence for hidden fluxes of mantle volatiles to the upper crust and atmosphere need to be considered when determining whether our planet is currently in net ingassing (that is, influx via subduction > outflux via degassing) or outgassing regime, which may have important impacts in terms of evaluating the role of long-term volatile cycling on terrestrial biogeochemical cycles.

Methods

Geological history

The Columbia River Basalt Group (CRBG) are flood basalts formed between 16.7 and 5.5 million years ago49. The flows originated from north–northwest-trending fissures in eastern Oregon, eastern Washington and western Idaho50,51. It has been proposed the eruption could have originated from the subduction related process such as slab tear33 or slab roll back52 or from the initiation of the Yellowstone hotspot plume53,54,55. The flows can be subdivided into seven formations (Steens, Imnaha, Grande Ronde, Picture Gorge, Prineville, Wanapum and Saddle Mountains basalts), which have different aerial extents over the basin and consistent of multiple lava flows51. Most flows have a columnar base as a result of slow cooling of ponded lava, which is overlain by irregular jointed basalt (entablature) and a vesicular and scoracious top that experienced more rapid cooling. The bedrock that underlies the Columbia River Basalt Group consists of pre-Miocene igneous, metamorphic and consolidated sedimentary rocks.

The Palouse Basin Aquifer is located on the eastern margin of the Columbia River Flood Basalt province and is contained in the mixed sediments of the Latah Formation and lava flows of the Columbia River Basalt Group39. This region is composed of 25 basalt flows that intruded into the basin from the west and disrupted westward drainages carrying eroded material from the basin mountains that are primarily composed of the granites of the Idaho Batholith. The sediments were captured between successive low-permeability basalt flows and alongside the higher-porosity zones of the basalts (such as the flow tops), representing recharge pathways from the eastern mountain fronts beyond the extent of the basalt. The interbedded sediments are clay rich, poorly sorted and are interspersed with coarse-grained channel deposits.

Analytical techniques

Sample collection

To understand the different processes affecting groundwater residence time tracers, we collected samples from 17 groundwater samples from drinking water wells within the Palouse Basin Aquifer (Extended Data Fig. 1). Noble gases were collected in 3/8” Cu tubes and sealed using stainless steel clamps following standard procedures (for example, ref. 56). Approximately 3.5 l of water was collected for high-precision noble gas measurement following the procedures of ref. 20. Radiocarbon was collected in 100 ml glass bottles using standard procedures for groundwater outlined in ref. 57. Temperature pH and salinity were determined onsite using a Hanna HI98194 multiparameter meter. This work is part of a broader hydrogeological study, and here we report helium and argon isotopes for the first time, alongside measurements of radiocarbon of DIC and neon, argon, krypton and xenon abundances that have been published to an online repository24.

Radiocarbon

Radiocarbon and carbon isotopes of DIC were analysed at the National Ocean Science Accelerator Mass Spectrometry (NOSAMS) Laboratory at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) following their standard protocols. Carbon-14 results are reported in percent modern carbon (pmC) and the reported analytical varied from 0.0012 to 0.0021 pmC.

We observe no relationship between in the δ13CDIC (−12.9 to −17.0‰) and DIC concentrations (2.33 to 4.43 mmol kg−1) (Extended Data Fig. 2), suggesting there is no dead carbon input from the soils to the system, which is expected in basalt aquifers as they contain low amounts of inorganic and organic carbon58,59. As a result, we do not apply a correction for dead soil carbon input to our radiocarbon age. We do, however, expect that there is some fraction of mantle-derived carbon in the system that is radiocarbon dead based on prior work25. However, we note that the maximum observed δ13C is −12.5‰, which is far below the mantle value and closer to that of DIC in equilibrium with soil CO2 ( ~ −15‰). Even in an extreme scenario in which 50% of the carbon is from the mantle rather than the atmosphere, the impact on radiocarbon ages is limited to the half life of 14C, ~5,700 years, below the prescribed uncertainty in our Monte Carlo simulations.

Noble gases

Noble gas concentration and helium isotope ratios were measured within the Jenkins Laboratory at WHOI using a quadrupole mass spectrometer for noble gas abundances and a custom static mass spectrometer for helium isotopes60. Noble gases were initially extracted from Cu tubes, transferred into glass bulbs and cryogenically transferred and gettered through a fully automated system. Full procedures can be found at https://www2.whoi.edu/site/igffacility/analytical-capabilities-for-water-measurements/.

High-precision noble gases

Triple-argon isotopes were measured via dynamic dual inlet isotope ratio mass spectrometry in the Seltzer Laboratory at WHOI. A total of 33 samples (17 wells) were analysed, with a pooled standard deviation of 0.02‰ for δ40Ar/36Ar, 0.01‰ for δ38Ar/36Ar and 0.03 ‰ for Δ40Ar. Gases were equilibrated into the headspace of the space vessel on an orbital shaker (minimum three days) in an isothermal chamber before the water was drained, leaving behind ~100 ml (ref. 20). The headspace gases were then transferred and purified by gettering with titanium sponge at 900 °C to quantitatively remove all non-noble gases before cryogenically transferring the remaining noble gases (Ar, Kr and Xe) into a dual-valve dip tube21. After a minimum of three hours equilibration in a water bath at 30 °C, the sample was then attached to a custom Thermo MAT 253 Plus and analysed following the procedures in ref. 21. Following measurement, data were corrected for matrix effects, nonlinearity and low-mass tail interferences on 36Ar and 38Ar from 40Ar (ref. 21).

Δ40Ar is defined as excess radiogenic 40Ar, relative to atmospheric air, in per mille. The original definition of Δ40Ar was presented in ref. 23. After several dozen additional measurements of Ar isotope ratios in air–water equilibration experiments61, here we update the definition to reflect these new data. By definition, Δ40Ar must be equal to 0 for air-saturated water, and therefore, assuming mass-proportional fractionation, δ40Ar/36Ar − (2 × δ38Ar/36Ar) should equal 0 in ASW. However, 2 × δ38Ar/36Ar is consistently higher than δ40Ar/36Ar in air-saturated water based on our measurements (and validated by MD simulations) by an average of 0.057 per mille in the range of 0 to 25 °C (Extended Data Fig. 4; ref. 61). We therefore re-define Δ40Ar as:

where 40Ar* and 40Aratm refer to radiogenic (excess) and atmospheric concentrations of 40Ar, respectively, and δ refers to deviations in the Ar isotope ratios from the well-mixed atmosphere (in ‰).

Using this definition, and assuming all gas-phase Ar isotope fractionation (gravity, thermal diffusion, water vapour flux) is mass proportional, then between 0 °C and 25 °C, this formula robustly ensures that Δ40Ar will be zero for all samples with purely atmosphere-derived 40Ar that may be fractionated by physical processes. The concentration of excess 40Ar (that is, 40Ar*) may be calculated using 40Ar and a measurement of total Ar by noting that the total measured concentration of 40Ar (40Artot, cm3STP gw−1) is equal to the sum of atmosphere-derived 40Ar (40Aratm) and radiogenic 40Ar (40Ar):

Note that 40Aratm reflects contributions and physical fractionation of argon from equilibrium dissolution at the water table, fractionation in overlying soil air (for example, by gravity) and from excess air input, hence the need to utilize the triple Ar isotope composition (Δ40Ar) to fully account for the fractionated atmospheric component of 40Ar.

Tritium in the Palouse Basin Aquifer

The decay of tritium 3H to 3He may result in an elevated 3He/4He in groundwater (for example, ref. 17). Although tritium was not measured as part of this study, previous measurements within region found very low levels of tritium indicate limited influence of very young groundwater and ruling it as a cause of elevated 3He (ref. 62).

Independent of this previous study, the scale of measured 3Hexs demonstrably exceeds any plausible amount of 3He production from tritium decay as reasoned below. First, we consider in situ production. In basaltic-based freshwater systems, a recent study estimated that 6.41 × 10−4 atoms of 3H per cm3 of fluid are generated annually63. When this is compared to the 3He content of ASW (Lake Baikal 10 °C), the 3He content represents 1.65 × 106 atoms 3He per cm3 of fluid. Consequently, assuming all 3H decays to 3He, to increase the starting 3He content of ASW by just 1%, would take 25.8 million years—almost twice that of the maximum Columbia River Basalt Group age (16.7 million years)49. As an alternative scenario, we also consider an unrealistically extreme example where a considerable amount of 1950s groundwater is present (say, 100 TU (tritium units) at the time of groundwater recharge), if this had all decayed to 3He, we would expect to see ~2.5 × 10−13 ccSTP g−1 (100 TU / 4.021 × 1014 to convert to cc g−1) of tritigenic 3He. Such an amount of tritigenic 3He is 1–2 orders of magnitude below the excess 3He measured in our highest 3He/4He samples (which display excess 3He on the orders of 10−11 and × 10−1 ccSTP g−1). Given the low radiocarbon activities in these samples, this scenario can be ruled out, and the likely amount of tritigenic 3He is probably at least an order of magnitude smaller. As a result, we are confident that tritigenic 3He represents <1% of 3He excess in these samples.

Isotopic source deconvolution and mixing analysis

In this section, we provide extra details on the source deconvolution of He and Ar isotopes.

Using measured data from each well (abundances of 4He, 3He, Ne, Ar, Kr and Xe, along with Δ40Ar), this deconvolution ultimately quantifies the sources of 3He, 4He and 40Ar.

The concentration of a noble gas isotope measured (\({C}_\mathrm{i}^{\mathrm{meas}}\)) represents the concentration inherited during atmospheric exchange during recharge (\({C}_\mathrm{i}^{\mathrm{atm}}\)) plus an excess contribution (\({C}_\mathrm{i}^{\mathrm{xs}}\)) arising from input from geological sources within or below the aquifer:

\({C}_\mathrm{i}^{\mathrm{atm}}\) is calculated for each sample using the CE model through PANGA64. It comprises both the equilibrium air–water component (that is, air-saturated water) and an excess air component that arises from dissolution of entrapped air bubbles during recharge65:

where Va / Vw is the initial air/water ratio in the recharge system and Vb / Vw is the final bubble/water ratio as the water becomes isolated after recharge. Hi is the Henry solubility coefficient for noble gas i and is a function of temperature (T) and salinity (S)66. \({C}_{\mathrm{iw}}^{\;{\mathrm{eq}}}\) is the expected concentration of noble gas i based on equilibrium between the groundwater and atmosphere (that is, air-saturated water), defined via Henry’s law as65:

Where Cia is the concertation of noble gas i in atmospheric air.

\({C}_{\mathrm{i}}^{\mathrm{xs}}\) comprises accumulation of geological noble gas isotopes from both in situ production (\({C}_{\mathrm{i}}^{\mathrm{in}\,\mathrm{situ}}\)) within the aquifer and from deeper external sources (\({C}_{\mathrm{i}}^{\mathrm{ext}}\)), which may be mantle or crustal in origin:

\({C}_{\mathrm{i}}^{\mathrm{xs}}\) is determined for 3He, 4He and 40Ar by subtracting measured concentrations from atmosphere-derived concentrations (equation (3)). Then \({C}_{\mathrm{i}}^{\mathrm{ext}}\) is determined by subtracting an in situ \({C}_{\mathrm{i}}^{\mathrm{in}\,\mathrm{situ}}\) contribution (for 4He and 3He) from \({C}_{\mathrm{i}}^{\mathrm{xs}}\) through a Monte Carlo simulation framework to assess uncertainty in externally derived Ar and He isotope abundances. In each Monte Carlo simulation (n = 1,000), the amount of helium in groundwater that accumulates from in situ production \(({C}_{\mathrm{i}}^{\mathrm{in}\,\mathrm{situ}})\) is calculated using the in situ accumulation rate (Pin situ in cm3 g−1 yr−1) determined from the purely crustal samples (main text) and the radiocarbon age (14Cage in years) of each sample:

We prescribe a Gaussian uncertainty for both \({P}_{\mathrm{i}}^{\mathrm{in}\,\mathrm{situ}}\) and \({14\atop}{\rm{C}}_{{\rm{age}}}\), separately, of 25% (1σ). For \({P}_{\mathrm{i}}^{\mathrm{in}\,\mathrm{situ}}\), this 25% uncertainty serves as a conservative estimate equal to twice the deviation (that is, ~12.5%) between the mean rate found in our analysis of the shallow crustal samples (1.49 × 10−11 cm3STP gw−1 yr−1 and the previously published value for CRB helium production (1.7 × 10−11 cm3STP gw−1 yr−1 (ref. 34)). Additionally, given that the 14C age only varies by a factor of three and considering that all of these samples are from within similar Columbia River Flood Basalt units, we would argue that it is reasonable to assume that the in situ helium production/accumulation rate is generally consistent. For \({14\atop}{\rm{C}}_{{\rm{age}}}\), the 25% uncertainty estimate accounts for potential biases in radiocarbon dating due to mixing or 14C-free DIC input, typically assumed to be on the order of several kyr. Notably, the impact of propagated errors on the subtraction of in situ helium in the deeper wells is a minor overall source of uncertainty in 4Heext because the 14C ages of the deeper samples (ranging from ~15–24 kyr) are only a factor of approximately three larger than those of the shallow crustal samples (ranging from ~5 to 10 kyr), and 4Hein situ represents at most 25% of total 4Hexs among the deeper, mantle-influenced samples. Similarly, we prescribe Gaussian uncertainties in \({C}_\mathrm{i}^{\mathrm{xs}}\) that come from the quadrature sum of the measured values and CE model estimates of \({C}_{\mathrm{i}}^{\mathrm{atm}}\) (ref. 24). The Monte Carlo analysis results in mean values and uncertainties (which are propagated through from assumed values and model and measured uncertainties) for \({C}_\mathrm{i}^{\mathrm{ext}}\), which also is used to constrain the endmember mixing model, with uncertainties propagated throughout. The mixing model assumes that the external volatile source reflects a binary mixture between mantle-like and crustal-like endmembers. We constrain the model in 3He/4He vs 4He/40Ar space (Fig. 4 and Extended Data Fig. 5) using \({C}_\mathrm{i}^{\mathrm{ext}}\) values for 40Ar, 4He and 3He from the 13 deep wells via least squares:

Where f is the proportion of crustal derived fluids. The mantle and crustal endmember compositions were variable to best fit the data. Notably, the crustal 4He/40Ar must be highly fractionated compared to the conical value, however the model is insensitive to the actual value.

Whereas our model used a Monte Carlo framework (n = 1,000 simulations) to account for error propagation in the determination of excess and external helium and argon, only the mean results were used to fit the mixing curve (that is, Fig. 4). The purpose of this mixing model is to determine which, if any, of the known canonical mantle endmembers could explain the data, by evaluating the fitted curve over the known range of mantle 4He/40Ar production ratios (that is, the known range goes from 4He/40Ar of 1 to 3). Our analysis asks the question, what is the maximum plausible mantle 3He/4He associated with the minimum plausible 4He/40Ar (that is, 4He/40Ar = 1), and by fully propagated uncertainties on 4Heext/40Arext and 3Heext/4Heext, we find the maximum mantle 3He/4He (associated with 4He/40Ar = 1) is 5.5 ± 0.4 RA (1 σ). This allows us, from a more robust statistical perspective, to demonstrate the compatibility of an SCLM source and the incompatibility of a plume or MORB source of mantle helium.

Potential subsurface tectonic driven devolatilization

Here we briefly explore the possibility that subsurface tectonic structures drive devolatilization. Two possible minor faults with minimal offset within the study region might exist39 (Extended Data Fig. 1). However, the basin is considered stable and lacks deformation40,41,67, and as a result we do not expect a substantial influence from movement along faults within the PBA. Although some studies have evidence of a minimal (~1%) slow velocity anomaly beneath the PBA68, which is very weak compared to other tomographic features within the region and probably has limited impact on volatile transport, however this anomaly has not been detected in other studies69. As a result, presently we cannot determine the cause of devolatilization and can only speculate a transport mechanism for these mantle volatiles. However, this does not impact our finding of non-volcanically active areas undergoing passive degassing of the SCLM.

Evaluating prospective fractionation of the source

It is possible that the mantle 4He/40Ar ratio could be theoretically lower than the mantle production ratio (2 ± 1 (ref. 8)) as a result of degassing8, and lower ratios of 4He/40Ar (< 1) have previously been observed in SCLM-derived xenoliths8,70. As a sensitivity test (Extended Data Fig. 5), we consider the 4He/40Ar resulting from mixing curves using different mantle 3He/4He endmembers (MORB = ~ 8 and Yellowstone Plume = ~19 (refs. 8,10,11,12)). We find that a MORB-like mantle endmember 3He/4He would require a 4He/40Ar of ~0.7 and a plume-like Yellowstone 3He/4He endmember would require a 4He/40Ar of ~0.3, both of which are considerably below the canonical mantle production value, therefore requiring even more fractionation of the mantle. We also note that some fractionation may have occurred during the presently unidentified transport mechanisms. If diffusion-controlled fractionation occurred, this could increase the 4He/40Ar* as 4He is more mobile than 40Ar. We suggest that the conceptually simplest (given its intraplate location and lack of plume evidence) and most likely source of mantle-derived volatiles to the PBA is diffusive degassing of the SCLM.

Data availability

The geochemical data that support the findings of this study are available in the extended data tables (He and Ar isotopes) and via Zenodo at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.12682511 (ref. 24). Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Bekaert, D. V. et al. Subduction-driven volatile recycling: a global mass balance. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 49, 37–70 (2021).

Barry, P. H. et al. Helium isotopic evidence for modification of the cratonic lithosphere during the Permo-Triassic Siberian flood basalt event. Lithos 216–217, 73–80 (2015).

Torgersen, T. Continental degassing flux of 4He and its variability. Geochem. Geophys. Geosystems 11, 6 (2010).

Torgersen, T. & Clarke, W. B. Helium accumulation in groundwater, I: an evaluation of sources and the continental flux of crustal 4He in the Great Artesian Basin, Australia. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 49, 1211–1218 (1985).

Stute, M., Sonntag, C., Deák, J. & Schlosser, P. Helium in deep circulating groundwater in the Great Hungarian Plain: flow dynamics and crustal and mantle helium fluxes. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 56, 2051–2067 (1992).

Kennedy, B. M. & van Soest, M. C. Flow of mantle fluids through the ductile lower crust: helium isotope trends. Science 318, 1433–1436 (2007).

Kulongoski, J. T. et al. Volatile fluxes through the Big Bend section of the San Andreas Fault, California: helium and carbon-dioxide systematics. Chem. Geol. 339, 92–102 (2013).

Graham, D. W. Noble gas isotope geochemistry of mid-ocean ridge and ocean island basalts: characterization of mantle source reservoirs. Rev. Mineral. Geochem. 47, 247–317 (2002).

Day, J. M. D. et al. The helium flux from the continents and ubiquity of low-3He/4He recycled crust and lithosphere. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 153, 116–133 (2015).

Lowenstern, J. B., Evans, W. C., Bergfeld, D. & Hunt, A. G. Prodigious degassing of a billion years of accumulated radiogenic helium at Yellowstone. Nature 506, 355–358 (2014).

Chiodini, G. et al. Insights from fumarole gas geochemistry on the origin of hydrothermal fluids on the Yellowstone Plateau. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 89, 265–278 (2012).

Broadley, M. W. et al. Identification of chondritic krypton and xenon in Yellowstone gases and the timing of terrestrial volatile accretion. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 117, 13997–14004 (2020).

Stuart, F. M., Burnard, P. G., Taylor, R. P. & Turner, G. Resolving mantle and crustal contributions to ancient hydrothermal fluids: He Ar isotopes in fluid inclusions from Dae Hwa W Mo mineralisation, South Korea. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 59, 4663–4673 (1995).

Torgersen, T. et al. Argon accumulation and the crustal degassing flux of 40Ar in the Great Artesian Basin, Australia. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 92, 43–56 (1989).

Warr, O., Giunta, T., Ballentine, C. J. & Sherwood Lollar, B. Mechanisms and rates of 4He, 40Ar and H2 production and accumulation in fracture fluids in Precambrian Shield environments. Chem. Geol. 530, 119322 (2019).

Befus, K. M., Jasechko, S., Luijendijk, E., Gleeson, T. & Bayani Cardenas, M. The rapid yet uneven turnover of Earth’s groundwater. Geophys. Res. Lett. 44, 5511–5520 (2017).

Jasechko, S. et al. Global aquifers dominated by fossil groundwaters but wells vulnerable to modern contamination. Nat. Geosci. 10, 425–429 (2017).

Holland, G. et al. Deep fracture fluids isolated in the crust since the Precambrian era. Nature 497, 357–360 (2013).

Heard, A. W. et al. South African crustal fracture fluids preserve paleometeoric water signatures for up to tens of millions of years. Chem. Geol. 493, 379–395 (2018).

Ng, J. et al. A new large-volume equilibration method for high-precision measurements of dissolved noble gas stable isotopes. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 37, e971 (2023).

Seltzer, A. M. & Bekaert, D. V. A unified method for measuring noble gas isotope ratios in air, water, and volcanic gases via dynamic mass spectrometry. Int. J. Mass Spectrom. 478, 116873 (2022).

Bender, M. L., Barnett, B., Dreyfus, G., Jouzel, J. & Porcelli, D. The contemporary degassing rate of 40Ar from the solid Earth. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 105, 8232–8237 (2008).

Seltzer, A. M. et al. The triple argon isotope composition of groundwater on ten-thousand-year timescales. Chem. Geol. 583, 120458 (2021).

Tyne, R. L. & Seltzer, A. M. Dissolved noble gas abundances and inorganic carbon isotopes from Palouse Basin groundwater wells (1.0) [Data set]. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.12682511 (2024).

Duckett, K. A. et al. Noble gases, dead carbon, and reinterpretation of groundwater ages and travel time in local aquifers of the Columbia River Basalt Group. J. Hydrol. 581, 124400 (2020).

Duckett, K. A. et al. Isotopic discrimination of aquifer recharge sources, subsystem connectivity and flow patterns in the South Fork Palouse River Basin, Idaho and Washington, USA. Hydrology https://doi.org/10.3390/hydrology6010015 (2019).

Aeschbach-Hertig, W., Peeters, F., Beyerle, U. & Kipfer, R. Palaeotemperature reconstruction from noble gases in ground water taking into account equilibration with entrapped air. Nature 405, 1040–1044 (2000).

Hilton, D. R. The helium and carbon isotope systematics of a continental geothermal system: results from monitoring studies at Long Valley caldera (California, USA). Chem. Geol. 127, 269–295 (1996).

Mackintosh, S. J. & Ballentine, C. J. Using 3He/4He isotope ratios to identify the source of deep reservoir contributions to shallow fluids and soil gas. Chem. Geol. 304–305, 142–150 (2012).

Ballentine, C. J. & Burnard, P. G. Production, release and transport of noble gases in the continental crust. Rev. Mineral. Geochem. 47, 481–538 (2002).

Ballentine, C. J., Burgess, R. & Marty, B. in Noble Gases in Geochemistry and Cosmochemistry vol. 47 539–614 (Geochemical Society, Mineralocical Society of America, 2002).

Medici, G. & Langman, J. B. Pathways and estimate of aquifer recharge in a flood basalt terrain; a review from the South Fork Palouse River Basin (Columbia River Plateau, USA). Sustainability 14, 11349 (2022).

Liu, L. & Stegman, D. R. Origin of Columbia River flood basalt controlled by propagating rupture of the Farallon slab. Nature 482, 386–389 (2012).

Reidel, S. P., Spane, F. A. & Johnson, V. G. Natural Gas Storage in Basalt Aquifers of the Columbia Basin, Pacific Northwest USA: A Guide to Site Characterization. PNNL-13962, 15020781 (PNNL, 2002); http://www.osti.gov/servlets/purl/15020781-61JNNk/

Warr, O. et al. Tracing ancient hydrogeological fracture network age and compartmentalisation using noble gases. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 222, 340–362 (2018).

Zakharova, N. V., Goldberg, D. S., Sullivan, E. C., Herron, M. M. & Grau, J. A. Petrophysical and geochemical properties of Columbia River flood basalt: implications for carbon sequestration. Geochem. Geophys. Geosystems 13, 11 (2012).

Solomon, D. K., Hunt, A. & Poreda, R. J. Source of radiogenic helium 4 in shallow aquifers: implications for dating young groundwater. Water Resour. Res. 32, 1805–1813 (1996).

Ballentine, C. J. & Sherwood Lollar, B. Regional groundwater focusing of nitrogen and noble gases into the Hugoton-Panhandle giant gas field, USA. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 66, 2483–2497 (2002).

Bush, J. H., Dunlap, P. & Reidel, S. P. Miocene evolution of the Moscow-Pullman Basin, Idaho and Washington. Idaho Geologic Survey https://www.idahogeology.org/product/t-18-3 (2018).

Buzzard, Q., Langman, J. B., Behrens, D. & Moberly, J. G. Monitoring the ambient seismic field to track groundwater at a mountain–front recharge zone. Geosciences 13, 9 (2023).

Burns, E. R., Morgan, D., Peavler, R. S. & Kahle, S. C. USGS Scientific Investigations Report 2010–5246 - Three-Dimensional Model of the Geologic Framework for the Columbia Plateau Regional Aquifer System, Idaho, Oregon, and Washington (USGS, 2010); https://pubs.usgs.gov/sir/2010/5246/index.html

Tian, Y. & Zhao, D. P-wave tomography of the western United States: insight into the Yellowstone hotspot and the Juan de Fuca slab. Phys. Earth Planet. Inter. 200–201, 72–84 (2012).

Muirhead, J. D. et al. Displaced cratonic mantle concentrates deep carbon during continental rifting. Nature 582, 67–72 (2020).

Barry, P. H. & Broadley, M. W. Nitrogen and noble gases reveal a complex history of metasomatism in the Siberian lithospheric mantle. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 556, 116707 (2021).

Zhang, X. J., Avice, G. & Parai, R. Noble gas insights into early impact delivery and volcanic outgassing to Earth’s atmosphere: a limited role for the continental crust. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 609, 118083 (2023).

O’Nions, R. K. & Oxburgh, E. R. Heat and helium in the Earth. Nature 306, 429–431 (1983).

Méjean, P. et al. Mantle helium in Southern Quebec groundwater: a possible fossil record of the New England hotspot. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 545, 116352 (2020).

Torgersen, T., Drenkard, S., Stute, M., Schlosser, P. & Shapiro, A. Mantle helium in ground waters of eastern North America: time and space constraints on sources. Geology 23, 675–678 (1995).

Barry, T. L. et al. Eruption chronology of the Columbia River Basalt Group in The Columbia River Flood Basalt Province. Special report 497 (eds Reidel, S. P. et al.) 45–66 (Geological Society of America, 2013).

Reidel, S. Igneous rock associations 15. The Columbia River Basalt Group: a flood basalt province in the Pacific Northwest, USA. Geosci. Can. 42, 151–168 (2015).

Reidel, S. P. et al. The Columbia River flood basalt province: stratigraphy, areal extent, volume, and physical volcanology. in The Columbia River Flood Basalt Province. Special report 497 (eds Reidel, S. P. et al) 21–42 (Geological Society of America, 2013).

Long, M. D. et al. Mantle dynamics beneath the Pacific Northwest and the generation of voluminous back-arc volcanism. Geochem. Geophys. Geosystems 13, 8 (2012).

Camp, V. E. Origin of Columbia River Basalt: passive rise of shallow mantle, or active upwelling of a deep-mantle plume? in The Columbia River Flood Basalt Province. Special Paper 497 (eds Reidel, S. P. et al.) 181–199 (Geological Society of America, 2013).

Hooper, P. R., Camp, V. E., Reidel, S. P. & Ross, M. E. The origin of the Columbia River Flood Basalt Province: plume versus nonplume models. in Plates, Plumes and Planetary Processes Special paper 430 (eds Foulger, G. R. & Jurdy, D. M.) Chap. 30 (Geological Society of America, 2007).

Kasbohm, J. & Schoene, B. Rapid eruption of the Columbia River flood basalt and correlation with the mid-Miocene climate optimum. Sci. Adv. 4, eaat8223 (2018).

Tyne, R. L. et al. A novel method for the extraction, purification, and characterization of noble gases in produced fluids. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 20, 5588–5597 (2019).

NOSAMS Sampling Procedures (WHO, 2022); https://www2.whoi.edu/site/nosams/wp-content/uploads/sites/124/2023/02/detailed-DI14C-sampling-procedures-1.pdf

Douglas, A. A., Osiensky, J. L. & Keller, C. K. Carbon-14 dating of ground water in the Palouse Basin of the Columbia river basalts. J. Hydrol. 334, 502–512 (2007).

Hinkle, S. R. Age of Ground Water in Basalt Aquifers Near Spring Creek National Fish Hatchery, Skamania County, Washington. (US Department of the Interior & US Geological Survey, 1996).

Stanley, R. H. R., Baschek, B., Lott III, D. E. & Jenkins, W. J. A new automated method for measuring noble gases and their isotopic ratios in water samples. Geochem. Geophys. Geosystems 10, 5 (2009).

Seltzer, A. M., Shackleton, S. A. & Bourg, I. C. Solubility equilibrium isotope effects of noble gases in water: theory and observations. J. Phys. Chem. B 127, 9802–9812 (2023).

Moxley, N. Stable Isotope Analysis of Surface Water and Precipitation in the Palouse Basin: Hydrologic Tracers of Aquifer Recharge. MS thesis, Washington State University (2012).

Warr, O., Smith, N. J. T. & Sherwood Lollar, B. Hydrogeochronology: resetting the timestamp for subsurface groundwaters. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 348, 221–238 (2023).

Jung, M. & Aeschbach, W. A new software tool for the analysis of noble gas data sets from (ground)water. Environ. Modell. Softw. 103, 120–130 (2018).

Aeschbach-Hertig, W., El-Gamal, H., Wieser, M. & Palcsu, L. Modeling excess air and degassing in groundwater by equilibrium partitioning with a gas phase: modelling gas partitioning. Water Resour. Res. 44, 8 (2008).

Jenkins, W. J., Lott, D. E. & Cahill, K. L. A determination of atmospheric helium, neon, argon, krypton, and xenon solubility concentrations in water and seawater. Mar. Chem. 211, 94–107 (2019).

McNamara, D. E. & Buland, R. P. Ambient noise levels in the continental United States. Bull. Seismol. Soc. Am. 94, 1517–1527 (2004).

Stanciu, A. C. & Humphreys, E. D. Upper mantle tomography beneath the Pacific Northwest interior. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 539, 116214 (2020).

Camp, V. E. Plume-modified mantle flow in the northern Basin and Range and southern Cascadia back-arc region since ca. 12 Ma. Geology 47, 695–699 (2019).

Moreira, M. & Sarda, P. Noble gas constraints on degassing processes. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 176, 375–386 (2000).

Acknowledgements

We thank J. Curtice, D. Lott and K. Cahill for technical and logistical support, and we are grateful to C. Acord, A. Kovisto, T. Musburger, T. Leachman, E. Johnson, P. Kimmell and the Palouse Basin Aquifer Committee for their support with groundwater sampling. This work was supported by the Weston Howland Postdoctoral Fellowship (R.L.T.), Dame Kathleen Ollerenshaw Fellowship (R.L.T.), National Science Foundation HS-2238641 (A.M.S., R.L.T., P.H.B.), Natural Environmental Research Council NE/X01732x/1 (M.W.B.), Agence Nationale de la Recherche grant ANR-22-CPJ2-0005-01 (D.V.B.), a Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada Discovery grant (O.W.) and National Science Foundation EAR- 2102457 (A.M.S.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The project was conceived by R.L.T. and A.M.S. R.L.T., A.M.S., M.W.B. and D.V.B. collected the samples. R.L.T., A.M.S. and I.M. performed the noble gas isotopic analysis. Data interpretation and modelling was developed by R.L.T., A.M.S., M.W.B., P.H.B., O.W., J.B.L. and W.J.J. R.L.T. prepared the first draft of the manuscript. All authors contributed to the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Geoscience thanks Hyunwoo Lee, Daniele Pinti, Nicholas Thiros and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editor: Alison Hunt, in collaboration with the Nature Geoscience team.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Extended Data Fig. 1 Map of study area showing the locations of the groundwater wells (n = 17) within the Palouse Basin Aquifer.

The colour of the symbol relates to the excess 40Ar (Δ40Ar) and symbol size represents the 3He/4He of the sample relative to air (R/RA). Samples with the highest Δ40Ar correlate with the highest measured 3He/4He. The “crustal” samples (Main text) are shown with a square symbol. Red dashed lines are the Moscow and South Fork fault, and the black dashed line represents a plunging anticline. The inset in the bottom right shows the location of the study area (red rectangle) within the Columbia River Basalts with the main urban areas labelled. Basemap is from ESSRI ArcGIS (https://www.arcgis.com/apps/mapviewer/index.html).

Extended Data Fig. 2 Carbon and Radiocarbon data from the groundwater samples.

Symbol colour correlates to the Δ40Ar of each groundwater sample (n = 17). a) The δ13C of dissolved oxygen concentration (DIC) as a function of DIC concentration. There is no correlation between δ13C and concentration. b) The δ13C of DIC vs radiocarbon in percent modern carbon (pmC). c) depth of groundwater well vs radiocarbon residence time (years). The four crustal samples identified in Fig. 2 are the shallow samples with residence times <10,000years and lowest Δ40Ar.

Extended Data Fig. 3 Triple Argon Plot (δ40Ar/36Ar vs δ38Ar/36Ar) for the groundwater samples (n = 17).

Mean ± 1σ uncertainties shown, where no errors are shown these are within symbol size. Unfilled samples represent the four “Crustal” samples (Main text). There is no correlation between the two parameters and therefore changes in δ40Ar/36Ar are not a result of fractionation.

Extended Data Fig. 4 Deviations and mass fractionation of Argon isotopes in Air Saturated Water relative to air.

Air saturated waters (n = 26) were measured at 1oC intervals from 1 to 25oC. Measured value ±1σ uncertainties are shown. a) δ40Ar/36Ar and 2 x δ38Ar/36Ar in air-saturated water between 0 and 25oC. There is an approximately constant offset in fresh water between 0 and 25 °C according to the updated solubility functions based on recent air-water equilibration experiments61. b) The offset between δ40Ar/36Ar and 2 x δ38Ar/36Ar at each temperature. The mean offset over this temperature range is shown by the blue dashed line and is calculated to be 0.057‰ which is adopted in the updated definition of Δ40Ar.

Extended Data Fig. 5 Mixing between potential mantle endmembers and crust for external 3He, 4He and 40Ar excess.

3He/4Heext vs 4He/40Ar*ext from the mantle influenced samples (n = 13) is used to model the expected mixing between a modelled mantle endmember and a crustal endmember (Grey dashed line). Measured values are given with 1σ uncertainties. The crustal 4He/40Ar* is likely highly fractionated and changing the value has minimal effect on the mantle endmember composition. The black square represents the most likely mantle composition (SCLM) based on a 4He/40Ar* within the mantle range (2 ± 18). The unfilled black squares represent the known Mid Ocean Ridge Basalt (MORB) and Yellowstone plume helium isotope ratio values8,10,11,12). Associated 4He/40Ar are significantly lower than the known mantle range for both MORB and the Yellowstone Plume and are unlikely to be the source of the mantle-derived fluids within the system.

Source data

Source Data

Source data files for Figs. 1–4, Extended Data Figs. 1–5 and Extended Data Tables 1–3.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tyne, R.L., Broadley, M.W., Bekaert, D.V. et al. Passive degassing of lithospheric volatiles recorded in shallow young groundwater. Nat. Geosci. 18, 542–547 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41561-025-01702-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41561-025-01702-7