Abstract

Tropical volcanic eruptions with a high volcanic explosivity index (≥5) impact the global climate system, but little is known about how they affect floods. Here, leveraging global climate model simulations with volcanic forcings and statistical relationships between seasonal climate drivers and peak discharge, we investigate the response of seasonal peak discharges at 7,886 streamgauges worldwide to three tropical explosive volcanic eruptions in the twentieth century: Agung 1963 (Indonesia), Santa Maria 1902 (Guatemala) and Pinatubo 1991 (Philippines), whose stratospheric aerosol plumes were distributed primarily in the Southern Hemisphere, primarily in the Northern Hemisphere and symmetrically across both hemispheres, respectively. For the eruptions with interhemispherically asymmetric aerosol distributions, tropical regions show more immediate and widespread responses to the eruptions than non-tropical regions, with a distinct interhemispheric contrast of decreasing (increasing) peak discharges in the hemisphere in which the eruption happened (did not happen). For the case of symmetric aerosol distribution, tropical (arid) regions have the strongest tendency to respond to the eruption by decreasing (increasing) peak discharges in both hemispheres. These regional flood responses are attributed mainly to seasonal precipitation changes across the climate regions. Beyond direct volcanic hazards, our study provides a global view of the secondary flood hazards resulting from hydroclimatic changes induced by large explosive eruptions.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$32.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $21.58 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

The worldwide basin boundary data for 7,886 streamgauges are obtained from different streamflow databases: African Database of Hydrometric Indices (ADHI) for Africa (available at https://doi.org/10.23708/LXGXQ9), Australian Bureau of Meteorology’s Hydrologic Reference Stations (HRS) for Australia (available at http://www.bom.gov.au/water/hrs/), United States Geological Survey Streamgauge NHDPlus Version 1 basins 2011 for conterminous United States (available at https://water.usgs.gov/lookup/getspatial?streamgagebasins) and Global Streamflow Indices and Metadata archive (GSIM) for the others (available at https://doi.pangaea.de/10.1594/PANGAEA.887477). The simulated seasonal peak flow datasets supporting the findings of this study are available via Zenodo at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.16037886 (ref. 35). Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

Codes that were used in this study are available upon request to the corresponding author.

References

Human Cost of Disasters: An Overview of the Last 20 Years (2000–2019) (CRED & UNDRR, 2020); https://www.undrr.org/publication/human-cost-disasters-overview-last-20-years-2000-2019

Kim, H., Villarini, G., Wasko, C. & Tramblay, Y. Changes in the climate system dominate inter-annual variability in flooding across the globe. Geophys. Res. Lett. 51, e2023GL107480 (2024).

Wasko, C., Nathan, R. & Peel, M. C. Changes in antecedent soil moisture modulate flood seasonality in a changing climate. Water Resour. Res. 56, e2019WR026300 (2020).

He, W., Kim, S., Wasko, C. & Sharma, A. A global assessment of change in flood volume with surface air temperature. Adv. Water Resour. 165, 104241 (2022).

Stewart, I. T. Changes in snowpack and snowmelt runoff for key mountain regions. Hydrol. Process. 23, 78–94 (2009).

Overpeck, J. T. & Cole, J. E. Abrupt change in Earth’s climate system. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 31, 1–31 (2006).

Shindell, D. T., Schmidt, G. A., Mann, M. E. & Faluvegi, G. Dynamic winter climate response to large tropical volcanic eruptions since 1600. J. Geophys. Res. 109, D05104 (2004).

Timmreck, C. et al. Linearity of the climate response to increasingly strong tropical volcanic eruptions in a large ensemble framework. J. Clim. 37, 2455–2470 (2024).

Hermanson, L. et al. Robust multiyear climate impacts of volcanic eruptions in decadal prediction systems. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 125, e2019JD031739 (2020).

Tejedor, E., Steiger, N. J., Smerdon, J. E., Serrano-Notivoli, R. & Vuille, M. Global hydroclimatic response to tropical volcanic eruptions over the last millennium. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 118, e2019145118 (2021).

Iles, C. E. & Hegerl, G. C. Systematic change in global patterns of streamflow following volcanic eruptions. Nat. Geosci. 8, 838–842 (2015).

Zuo, M., Zhou, T. & Man, W. Hydroclimate responses over global monsoon regions following volcanic eruptions at different latitudes. J. Clim. 32, 4367–4385 (2019).

Trenberth, K. E. & Dai, A. Effects of Mount Pinatubo volcanic eruption on the hydrological cycle as an analog of geoengineering. Geophys. Res. Lett. 34, 1–5 (2007).

Zuo, M., Zhou, T. & Man, W. Wetter global arid regions driven by volcanic eruptions. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 124, 13648–13662 (2019).

Liu, J. et al. Global changes in floods and their drivers. J. Hydrol. 614, 128553 (2022).

Yang, W. et al. Climate impacts from large volcanic eruptions in a high-resolution climate model: the importance of forcing structure. Geophys. Res. Lett. 46, 7690–7699 (2019).

Liu, F. et al. Global monsoon precipitation responses to large volcanic eruptions. Sci. Rep. 6, 24331 (2016).

Colose, C. M., LeGrande, A. N. & Vuille, M. Hemispherically asymmetric volcanic forcing of tropical hydroclimate during the last millennium. Earth Syst. Dyn. 7, 681–696 (2016).

Robock, A. in The Encyclopedia of Volcanoes (ed. Sigurdsson, H.) 935–942 (Academic, 2015); https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-385938-9.00053-5

Iles, C. E., Hegerl, G. C., Schurer, A. P. & Zhang, X. The effect of volcanic eruptions on global precipitation. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 118, 8770–8786 (2013).

Zhuo, Z., Kirchner, I., Pfahl, S. & Cubasch, U. Climate impact of volcanic eruptions: the sensitivity to eruption season and latitude in MPI-ESM ensemble experiments. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 21, 13425–13442 (2021).

Iles, C. E. & Hegerl, G. C. The global precipitation response to volcanic eruptions in the CMIP5 models. Environ. Res. Lett. 9, 104012 (2014).

Erez, M. & Adam, O. Energetic constraints on the time-dependent response of the ITCZ to volcanic eruptions. J. Clim. 34, 9989–10006 (2021).

Rodwell, M. J. & Hoskins, B. J. Monsoons and the dynamics of deserts. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 122, 1385–1404 (1996).

Pierson, T. C. & Major, J. J. Hydrogeomorphic effects of explosive volcanic eruptions on drainage basins. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 42, 469–507 (2014).

Todesco, M. & Todini, E. Volcanic eruption induced floods. a rainfall-runoff model applied to the Vesuvian Region (Italy). Nat. Hazards 33, 223–245 (2004).

Thomason, L. W. et al. A global space-based stratospheric aerosol climatology: 1979–2016. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 10, 469–492 (2018).

Arfeuille, F. et al. Volcanic forcing for climate modeling: a new microphysics-based data set covering years 1600-present. Clim. Past 10, 359–375 (2014).

Kim, H. & Villarini, G. On the attribution of annual maximum discharge across the conterminous United States. Adv. Water Resour. 171, 104360 (2023).

Do, H. X., Gudmundsson, L., Leonard, M. & Westra, S. The Global Streamflow Indices and Metadata Archive (GSIM)-Part 1: the production of a daily streamflow archive and metadata. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 10, 765–785 (2018).

Tramblay, Y. et al. ADHI: the African Database of Hydrometric Indices (1950–2018). Earth Syst. Sci. Data 13, 1547–1560 (2021).

Mann, H. B. & Whitney, D. R. On a test of whether one of two random variables is stochastically larger than the other. Ann. Math. Stat. 18, 50–60 (1947).

Wilcoxon, F. Individual comparisons by ranking methods. Biometr. Bull. 1, 80–83 (1945).

Beck, H. E. et al. Present and future Köppen–Geiger climate classification maps at 1-km resolution. Sci. Data 5, 180214 (2018).

Kim, H. Global response of floods to tropical explosive volcanic eruptions. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.16037886 (2025).

Acknowledgements

The research was supported in part by funding provided by Princeton University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.K. processed the data, conducted the analyses, created the figures, interpreted the results and prepared the paper. G. Villarini designed the study, interpreted the results and prepared the paper. W.Y. processed the data, interpreted the results and prepared the paper. G. Vecchi interpreted the results and prepared the paper. All authors reviewed and edited the final version of the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Geoscience thanks Jon Major and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editor: Tamara Goldin, in collaboration with the Nature Geoscience team.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Extended Data Fig. 1 Maps showing the location of three volcanoes (triangles) and streamgauges used in this study.

The numbers in parentheses in the titles of the top and middle panels and on the x-axis of the bottom panel represent the number of streamgauges within each climate region. Basin boundaries are shown with bold lines. Colored pixels on land indicate the corresponding climate regions. The boxplots (bottom panel) show the distribution of correlation coefficients between observed and modeled seasonal peak flows across streamgauges stratified by four climate types. In the boxplot, the limits of the box (whiskers) represent the 25th and 75th (5th and 95th) percentiles, while the line inside of the box indicates the median. Figure modified from ref. 2.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Sensitivity of the number of streamgauges with no overlapping basins to the basin size thresholds.

The point with red circle indicates the maximum number of streamgauges with no overlapping basins which is finally selected to assess the impact of overlapping basins on prevalence of flood responses.

Extended Data Fig. 3 Changes over time in the prevalence of the 2-year return interval discharges in response to tropical volcanic eruptions.

Same as Fig. 1 in the main text, but for 4,886 streamgauges with non-overlapping basins only.

Extended Data Fig. 4 Changes over time in the prevalence of the 2-year return interval discharges in response to tropical volcanic eruptions.

Same as Fig. 1 in the main text, but for: a) 6,336 streamgauges whose statistical flood models show a correlation coefficient of at least 0.3 between observed and modeled peak flows for all four seasons; and b) 4,193 streamgauges whose statistical flood models show a correlation coefficient of at least 0.5 between observed and modeled peak flows for all four seasons.

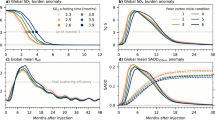

Extended Data Fig. 5 Changes over time in the regional average of the absolute changes in the magnitude of the 2-year return interval discharges in response to tropical volcanic eruptions.

Changes in the discharge magnitude due to the eruptions are calculated by subtracting the ensemble median of 30 non-eruption simulations from that of 30 eruption simulations. The regional average values are then obtained by taking the median across the streamgauges stratified by tropical (magenta line), arid (orange line), temperate (green line), and cold (light blue line) regions. The lines above (below) zero show the results for streamgauges experiencing increasing (decreasing) discharge due to eruptions. The vertical red line indicates the season in which the eruption occurred. The shaded areas separated by different colors and vertical black lines represent each year, from the first (YR1) to the fourth year (YR4) after the eruption. Panels show results for Agung (Indonesia), Santa Maria (Guatemala), and Pinatubo (Philippines) eruptions.

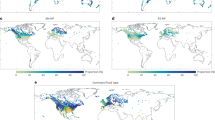

Extended Data Fig. 6 Global responses of the 2-year return interval discharges and seasonal temperature to tropical volcanic eruptions.

The red (blue) circles show the streamgauges having statistically significant decrease (increase) in the 2-year return interval discharge due to the eruptions. Grid cells inland indicate absolute change in the median of the season-averaged temperatures across 30 ensemble members. The redder grids represent greater decreases, while the bluer grids represent greater increases in temperature due to the eruptions. Three rows represent the results for September-November season for Agung (Indonesia), December-February season for Santa Maria (Guatemala), and March-May season for Pinatubo (Philippines) eruptions, from top to bottom. Three columns represent the results of the first (YR1), second (YR2), and third year (YR3) after eruptions, from left to right.

Extended Data Fig. 7 Responses of discharges for different return intervals to tropical volcanic eruptions.

Percentages of streamgauges showing significant decreases (first and third columns) and increases (second and fourth columns) in peak discharges calculated for 2-, 10-, 50-, and 100-year return intervals. The darker the color, the greater the discharge return interval. The vertical red line indicates the season in which the eruption occurred. The shaded areas separated by different colors and vertical black lines represent each year, from the first (YR1) to the fourth year (YR4) after the eruption. Panels show results for Agung (Indonesia), Santa Maria (Guatemala), and Pinatubo (Philippines) eruptions.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figs. 1–8.

Supplementary Data 1

Source data for supplementary figures.

Source data

Source Data Fig. 1

Statistical source data.

Source Data Fig. 2

Statistical source data.

Source Data Fig. 3

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 1

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 2

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 3

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 4

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 5

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 6

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 7

Statistical source data.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Kim, H., Villarini, G., Yang, W. et al. Global response of floods to tropical explosive volcanic eruptions. Nat. Geosci. 18, 983–988 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41561-025-01782-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41561-025-01782-5