Abstract

The origin of geochemically enriched mantle in the asthenosphere is important to understanding the physical, thermal and chemical evolution of Earth’s interior. While subduction of oceanic sediments and deep mantle plumes have been implicated in this enrichment, they cannot fully explain the observed geochemical trends. Here we use geodynamic models to show that enriched mantle can be liberated from the roots of the subcontinental lithospheric mantle by highly organized convective erosion, a process tied to continental rifting and break-up. We demonstrate that this ‘chain’ of convective instabilities sweeps enriched lithospheric material into the suboceanic asthenosphere, in a predictable and quantifiable manner, over tens of millions of years—potentially faster for denser, removed keels. We test this model using geochemical data from the Indian Ocean Seamount Province, a near-continent site of enriched volcanism with minimal deep mantle plume influence. This region shows a peak in enriched mantle volcanism within 50 million years of break-up followed by a steady decline in enrichment, consistent with model predictions. We propose that persistent and long-distance lateral transport of locally metasomatized, removed keel can explain the billion-year-old enrichments in seamounts and ocean island volcanoes located off fragmented continents. Continental break-up causes a reorganization of shallow mantle dynamics that persists long after rifting, disturbing the geosphere and deep carbon cycle.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Enriched mantle (EM) components are parts of Earth’s mantle that contain distinct concentrations of certain trace elements relative to the average or depleted mantle (DM)1. EM components, an enduring feature of the asthenosphere frequently detected in ocean island basalts (OIBs), give rise to heterogeneous radiogenic isotope compositions in mantle domains1,2. While compositionally diverse at all scales3,4,5, the ‘Enriched Mantle 1’ (EM1) end member is typically characterized by higher 87Sr/86Sr, lower 143Nd/144Nd and generally lower 206Pb/204Pb ratios compared with DM1,2,6. EM1-type enrichment is frequently associated with continental margins, such as the Walvis Ridge off the coast of Africa in the Atlantic Ocean7 (Extended Data Fig. 1), and the Indian Ocean Seamount Province, originally off northeastern Australia8. What is lacking are mechanistic models that show how this enrichment, particularly prominent in the earliest volcanism at such sites7,8, may occur. We propose that organized chains of Rayleigh–Taylor instabilities, which sweep along continental keels following break-up9,10, can systematically disturb ancient deep lithospheric reservoirs, flushing the removed enriched components into the suboceanic asthenosphere over tens of millions of years (Myr).

Various sources have been proposed for EM1’s origins, including subducted oceanic crust with pelagic sediments2; deeply subducted lower continental crust11; deep-rooted mantle plumes that mobilize subducted material12; and recycled subcontinental lithospheric mantle (SCLM)4,8,13. Notably, the EM1 group of OIBs share common features, yet each occurrence exhibits diverse trends that extrapolate to a variety of Pb isotope ratios at high Sr and low Nd isotope ratios14. This suggests that EM1 was not generated from a homogeneous source in a single event, but rather reflects input from a mosaic of rocks of varying ages.

The mantle reservoirs feeding OIBs probably remained chemically isolated for 1–2 billion years (Gyr), allowing isotopic systems (for example, U/Pb and Sm/Nd) to evolve after shallow (that is, upper mantle or crustal) fractionation15. Chemical isolation can occur within the lowermost SCLM, where EM1-type enrichment can occur through metasomatic fluids driven off subducting slabs16 (Fig. 1). Geophysical and geochemical constraints17,18 suggest these fluids ascend and impregnate the SCLM keel4,19 and accumulate in multiple stages over several Gyr (refs. 20,21,22), isolating them from convective mantle. During continental break-up, enriched SCLM domains become entrained into the suboceanic asthenosphere8,17,18, although the duration and length scales of this process remain uncertain. Such enriched domains can contain carbonate and hydrous phases, lowering the solidus temperature during decompression melting, fuelling OIB volcanism21.

EM components accumulate over Gyr timescales through multiple phases of enrichment. This can occur through the upwelling (that is, return flow) of carbon-bearing melts from the mantle transition zone, as well as the percolative upward transport of carbonated melts sourced from down-going subducted oceanic slabs. This process metasomatizes the cratonic keels, resulting in spatially heterogeneous age profiles and EM compositions. Diamond symbols denote regions where diamonds are thought to accumulate.

The mechanisms for entraining lowermost SCLM into the asthenosphere during continental break-up include thermal erosion and lateral advection directly under the rift zone18,23. Continental break-up drives lithospheric thinning, giving rise to upwelling and possibly decompression melting involving laterally flowing cratonic material23. Such processes are generally thought to be restricted to the immediate post-rift phase. The persistence of EM1 signatures in volcanic rocks erupted many tens of Myr after local break-up24,25, and the presence of these signatures within contiguous chains or areas of volcanism over similar periods12,17 implies an enduring supply of EM1-type material that is not well explained by existing models.

We investigate the possibility that EM1-type domains are supplied to the shallow asthenosphere from the SCLM through the far-field effects of rifting9,10. Active rifting and necking—the pronounced thinning of the lithosphere as plates separate—creates lithospheric edges, introducing lateral temperature and viscosity gradients. These gradients generate edge-driven convection (EDC) cells within the underlying mantle26,27, which both mechanically disturb the adjacent continental root9 and deflect local mantle upwellings28. Indeed, cool ‘hotspots’ in the oceans may either have a shallow source or result from deep plume material being cooled and redistributed by small-scale convection28,29,30. Furthermore, some oceanic intraplate lavas have been linked to small-scale sublithospheric convective instabilities associated with upwelling induced by buoyant decompression melting31. In addition to organizing small-scale convection near the rift, EDC can instigate a chain of Rayleigh–Taylor instabilities that systematically migrate continent-wards along the lithospheric root9,10. While this process destabilizes the metasomatized continental keel, driving low-degree melting, devolatization and kimberlite volcanism9, much of the removed keel is entrained into the asthenosphere where it either sinks or migrates ocean-wards. Crucially, destabilization of the keel can continue tens of Myr after continental break-up, reflecting the time taken for instabilities to migrate into craton interiors9,10. Therefore, lithospheric contamination of asthenospheric mantle may be much more protracted than previously envisaged.

Characterizing EM1-type volcanism

To evaluate whether convective removal of lithospheric keels could influence magma petrogenesis in the oceanic realm, we first studied the geochemical characteristics of kimberlites and adjacent contemporaneous oceanic volcanism. Kimberlites, which erupted extensively across the cratons during Gondwana break-up32, provide a window into the geochemical evolution of the deep SCLM they sample9. To examine the relationship between SCLM and EM1, we consider a compilation of kimberlite radiometric ages and geochemical data from Southern Africa including ϵNdi (ref. 33) and (87Sr/86Sr)i (ref. 34) (Fig. 2a–c and Extended Data Fig. 1). Earlier kimberlites are more enriched and show both EM1 and subduction zone signatures, with varying degrees of crustal contamination (Fig. 2a–c). Kimberlite compositions then abruptly become depleted, with Sr and Nd isotope trends towards DM end members35 (Fig. 2a), suggesting a greater influence of SCLM assimilation earlier in kimberlite petrogenesis, followed by stronger input of asthenospheric mantle (Fig. 2b,c). This evolution implicates SCLM delamination and adiabatic upwelling of asthenosphere9. Notably, delamination thins the lithosphere and can drive continental exhumation10,21,36.

a, ϵNdi versus (87Sr/86Sr)i from kimberlites of the Kaapvaal craton33 and Rajmahal, India58, and basaltic volcanics from the Walvis Ridge7,37 and the Indian Ocean—that is, the Kerguelen Plateau and the CHRISP8; also shown are fields for kimberlites and EM1, prevalent mantle (PREMA) and DM compositions59. b, The evolution of (87Sr/86Sr)i in perovskites from African kimberlites from ref. 34; also shown is the mica–amphibole–rutile–ilmenite–diopside (MARID) end member defined from kimberlite xenoliths (reflecting lithospheric mantle) and kimberlite melt end member defined largely by phlogopite–ilmenite–clinopyroxene (PIC) xenoliths22. c, The evolution of ϵNdi in Kaapvaal kimberlites33; solid red lines show statistically defined change points (using CPR) and two-sigma uncertainty bounds of the two averages (thin red lines) before and after the change point at 114 Ma (ref. 9); this coincides with the timing of lithospheric delamination (dashed vertical line at 114 Ma)9. d, The evolution of (87Sr/86Sr)i at Walvis Ridge7,37. e, The evolution of ϵNdi at Walvis Ridge7,37. In both d and e, a change point occurs at 107 Ma, 13 Myr after accelerated rifting and exhumation at ~120 Ma (Extended Data Fig. 2). f, The frequency of individual dated volcanic samples from Walvis, with the earliest known volcanism occurring at 114 Ma (radiometric ages from refs. 7,37). JUR, Jurassic.

The mantle flow beneath Africa is driven by a large-scale upwelling that diverges beneath the continent, causing westward mantle movement beneath the South Atlantic continental margins of Africa36. This prevailing mantle flow, generated above the deeper Couette (shear) flow, should transport decoupled SCLM into the Atlantic asthenosphere36. Lithospheric delamination on this scale should be discernible in oceanic basalts near the continent–ocean boundary (COB). To investigate this, we examine geochronological and isotopic data from volcanic rocks on Walvis Ridge7,37 (Fig. 2d–f) near the Congo and Kaapvaal cratons (Extended Data Fig. 1). The earliest Walvis volcanism at 114 Ma (ref. 7) followed accelerated rifting and break-up38 (Fig. 2d,e), intense exhumation along adjacent margins (Extended Data Fig. 2) and delamination of the distant Kaapvaal craton9 (Fig. 2b,c). Walvis volcanics lag behind the Etendeka plume volcanism (Extended Data Fig. 1) by ~20 Myr and display enriched compositions, which are followed by a sharp transition to more depleted signatures—paralleling the trend seen in kimberlites (Fig. 2). To investigate the timing, we apply a conjugate partitioned recursion (CPR)—a computational approach that can identify change points in time series (Methods)—finding that the Walvis volcanics indeed show a similar shift to depleted compositions, albeit ~7 Myr later (Fig. 2d,e). Accordingly, we suggest that the early phases of Walvis volcanism primarily reflect SCLM removal during South Atlantic rifting and break-up, potentially influenced by interaction with the residual mantle upwellings28 that aided break-up12,39.

The question remains, however, whether the dynamics of convective removal can account for the transport of SCLM to the suboceanic asthenosphere on timescales consistent with the observed changes in geochemical signatures (Fig. 2).

Geodynamic modelling of rifting and break-up

We address this question by utilizing thermomechanical simulations (building on refs. 9,10) to quantify the magnitude and rate at which enriched material is removed from keels and delivered to the suboceanic asthenosphere (Methods). Previous simulations show that Rayleigh–Taylor instabilities initiate at the lithospheric discontinuity and migrate towards the continent, stripping weak, metasomatized keels9,10. While we focus on simulations that best match observations from kimberlites9 and exhumation patterns10, we used additional experiments to assess the effects of varying lithospheric thickness, two-way plate motion, alternative mantle rheologies (including variations in viscosity of the asthenosphere and metasomatized mantle lithosphere9) and a deeper model domain (Methods). The process of sequential delamination occurs in all scenarios as described in the reference model (Fig. 3a). Migration rates of instabilities differ slightly from the reference model (Fig. 3), but are in full agreement with observational constraints9,10 (Methods).

a, Simulations showing convective removal of lithospheric keels, which migrates towards cratonic interiors over time9,10; enriched material is removed and transported rift-wards and into the suboceanic asthenosphere (left of dashed line) where it is then transported upwards by convection cells. b, Top: flow rate of decoupled lithospheric material—crossing a transect 200 km from the COB (dashed vertical line in a)—into the suboceanic asthenosphere (SOA) over time, exhibiting pulsing behaviour. Three alternative models are shown in red, green and grey (Methods), and a slow divergence scenario is also considered (Extended Data Fig. 3). Bottom: the cumulative frequency of SCLM entering the SOA for these different models, with the growth rate of this SCLM addition declining over time. c, Histogram and PDF of time estimates for decoupled SCLM to travel from the transect below the proto-rift (see a) to the base of the oceanic lithosphere (Extended Data Fig. 6) from two locations (150 and 200 km from COB; see dashed line in a). d, The same data as an empirical cumulative distribution function.

We observe that a large component of the removed keel is entrained into convection cells and transported ocean-wards (Fig. 3a). To estimate the flux of SCLM into the suboceanic asthenosphere, we quantify the total amount of this material below the lithospheric discontinuity in the model domain at 0.5-Myr intervals (Methods). In the reference model, SCLM enters the suboceanic asthenosphere within ~2 Myr of break-up, defined as the point when the continental lithosphere within the rift is fully separated38. Its abundance peaks within 15–50 Myr post-break-up and declines over time, reflecting the progressive removal and exhaustion of lithospheric keels by convective erosion (Fig. 3a,b). To test the sensitivity of this result, we vary the extension velocity (5 mm yr−1 and 20 mm yr−1, compared with 10 mm yr−1 in the reference model) and introduce symmetric boundary conditions (Methods; Supplementary Videos 1–5). These changes shift the timing of SCLM flux peaks but, except in slow-extension cases (Extended Data Fig. 3), do not change the overall pattern: peaks consistently occur within ~50 Myr of break-up and broadly decline over time (Fig. 3b). Faster divergence rates, which are common during the rift–drift transition38, lead to an accelerated ‘mantle wind’ and more vigorous convection (Supplementary Video 3), transporting detached SCLM more rapidly into the oceanic asthenosphere (Fig. 3b). By contrast, under slow extension, where rifting is protracted (lasting ~140 Myr), the main peak occurs during late-stage rifting (Extended Data Fig. 3). Such cases are not relevant to the scenarios discussed below and are not considered further. Expanding the model domain depth to 410 km has little effect on the spacing (thus, wavelength) of instabilities, which decreases slightly from 270 km to 255 km (Methods).

In all models, we observe clear spikes—periods lasting several Myr—when decoupled SCLM enters the suboceanic asthenosphere at high flow rates (Fig. 3b). To detect whether these pulses are cyclic, we apply a Lomb–Scargle periodogram—an algorithm used to identify periodic signals in unevenly sampled data40 (Methods)—finding that pulses exhibit a statistically periodicity (P value <0.05) of 5–6 Myr (Extended Data Fig. 4). While the SCLM flux does not directly correspond to EM1, the EM1 field closely overlaps with xenoliths and volcanics representing the lowermost SCLM41,42 (Fig. 2a). We therefore assume that EM1 scales with the SCLM tracer in our models. Crucially, our model does not require all this SCLM to melt to generate volcanism: it simply predicts where and when candidate EM1 reservoirs were present and could have viably contributed to melting.

To further test the operating limits of our mechanism, we conducted 27 numerical experiments varying the density and viscosity of the metasomatized lithospheric keel, while holding all other parameters constant. The results reveal three broad behavioural regimes (Extended Data Fig. 5). For intermediate densities (3,290–3,310 kg m−3; 0.3–0.9% above the ambient SCLM), the system evolves comparably to the reference case (Fig. 3). At higher densities (≥3,320 kg m−3), dripping has concluded by 50 Myr post-rift onset, with detached keel pockets entrained in small-scale convection (Extended Data Fig. 5). Here, rapid flushing of removed material and shorter residence times imply that associated EM-type magmatism would peak during or soon after rifting. At lower densities (≤3,280 kg m−3), buoyancy inhibits dripping, instead favouring lateral flow of metasomatized material towards the rift (Extended Data Fig. 5), akin to the underplating of ref. 23. These findings accord with theoretical predictions: migration rates increase with density and decrease with increasing viscosity (higher activation energies)9. These experiments define a viable parameter space for the proposed mechanism (Extended Data Fig. 5), most of which result in transport of removed SCLM into the suboceanic asthenosphere.

This removed material is entrained into convection cells, tied to lithospheric edge effects (Fig. 3a), which may superpose on the expected 5–6 Myr periodicity. This raises the question of the timescale required for EM signals to manifest in oceanic volcanism. To explore this, we consider a range of indicative length scales (350–500 km) and maximum velocities taken from geodynamic simulations for a Monte Carlo analysis of convection cells (Extended Data Fig. 6; Methods). This yields a first-order estimate of the time lags, with median and mean ascent times of ~8 and ~9 Myr, respectively (Fig. 3c,d).

These results allow us to make testable predictions. First, enriched SCLM should enter the suboceanic asthenosphere within a few Myr of break-up (Fig. 3b and Supplementary Videos 1–5), but then requires 5–15 Myr to reach the surface (Fig. 3c,d). Second, the supply of enriched material should persist for tens of Myr, gradually declining over time, with peak supply occurring within ~50 Myr of break-up (Fig. 3b), potentially sooner in cases where higher-density keels delaminate (Extended Data Fig. 5). Third, the transfer rate of enriched material to the surface should be pulsed, reflecting episodic delamination operating on 6-million-year cycles (Fig. 3b), modulated by mantle convection on 8-million-year cycles (Fig. 3c,d). While such periodicity could be detected in the tempo of oceanic volcanism, there are currently insufficient data to rigorously test this.

Testing convective erosion models for EM signal

To test the first two predictions, we examine ocean crust and seamount provinces that are not associated with high-μ (HIMU, where μ is the ratio of238U/204Pb) mantle plume signatures to avoid the complication of volcanism sampling deep mantle sources. This setting is best exemplified by the Indian Ocean, where mid-ocean ridge basalt (MORB) exhibits more enriched compositions than those of the Pacific and North Atlantic41,43. In some cases, this enrichment has been linked to shallow recycling of continental material, including the SCLM and lower crust8,44,45,46,47,48. Specifically, we investigate the Christmas Island Seamount Province (CHRISP) in the eastern Indian Ocean (Fig. 4)—far from known deep mantle plume influence30—where EM1-enriched end members were identified in the SCLM of North West Australia8. We include the nearby Investigator Fracture Zone (IFZ)41 (Fig. 4b), where early-stage enrichment from delaminated SCLM during Gondwana break-up is thought to have declined over time through mixing with depleted upper mantle41.

a, Plate tectonic reconstruction at 50 Ma (South Pole Lambert azimuthal equal-area projection) showing the age distribution of volcanic seamounts from refs. 8,41. The grey arrow indicates the general age progression away from western Australia. b, Present-day locations of the same seamounts in the eastern Indian Ocean, as shown in Fig. 5. VMVP, Vening Meinesz volcanic province. Credits: The reconstruction in panel a was created using QGIS software under a GNU license. The map background in panel b was created with data from GeoMapApp v.3.7.4 under a CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 US license.

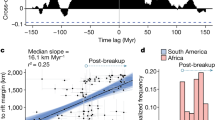

We compile radiometric ages and isotopic characteristics of volcanic rocks spanning the IFZ41 and the CHRISP (Fig. 5a and Supplementary Table 1), where they are typically 0–25 Myr younger than the underlying oceanic crust8. We applied a weighted bootstrap analysis to mitigate the effect of spatial sampling bias (Methods). We identify an early peak in EM1 involvement in melting within 40–60 Myr of the final break-up of India from Antarctica–Australia, which occurred ~126 Ma (refs. 38,49) (Fig. 5a). The earliest post-break-up volcanism occurred ~116 Ma (10 Myr post-break-up), closely consistent with model predictions (Fig. 3c). Volcanics closer to Australia exhibit greater enrichment, suggesting a predominantly Australian SCLM source, as proposed by Hoernle et al.8. Indeed, the occurrence of kimberlite volcanism in western Australia at 120 Ma (ref. 32) may indicate disruption of the SCLM keel then9. The isotopic trajectory of volcanics trends towards West Australian lamproites8 and the proposed EM1 end member of ref. 42, while some data trend towards African kimberlites and the EM1 end member of ref. 41 (Fig. 5a). Variable Pb isotope signatures probably reflect age heterogeneity in the SCLM, sourced from different continental regions with varying storage durations. We infer a long-term decline in the contribution of enriched material to melting, reflected, for example, in a steady increase in (206Pb/204Pb)i over time (r2 = 0.71; Fig. 5b), similar to other isotope systems (for example, Extended Data Fig. 7). These trends mirror the long-term decline in enrichment inferred in our geodynamic models (Fig. 3b).

a, (208Pb/204Pb)i versus (206Pb/204Pb)i of volcanics spanning the CHRISP8 and the IFZ41, coloured by age (n = 31). The fields for EM1, lamproites and kimberlites are from ref. 41, and another proposed EM1 composition (star) is from ref. 42. NHRL, Northern Hemisphere Reference Line; SA, South Africa b, (206Pb/204Pb)i of the above volcanics over time, coloured by ϵNdi (n = 30; data from refs. 8,41), with the EM1 field41 shown in pink. Linear regressions (n = 1,000 from weighted bootstrap resampling procedure; Methods) are shown in blue; the resulting samples yield an r2 range of 0.34–0.91, with a median of 0.71. The data support the hypothesis that convective SCLM removal enriches the suboceanic asthenosphere, driving the early peak and gradual decline of EM components.

We observe similar trends at other classic EM sites (albeit where cold/warm plumes are present30), namely the Kerguelen Plateau (EM2 end member), Broken Ridge and Ninety East Ridge in the Indian Ocean, which once formed a contiguous province (Extended Data Fig. 8a and Supplementary Tables 1–3). The early phases of EM-type magmatism in these regions are broadly similar to the IFZ and CHRISP regions (Fig. 5): enriched signatures peak within 50–60 Myr of break-up, superimposed on a long-term decline, as reflected in a steady increase in (206Pb/204Pb)i over time (r2 = 0.57, n = 181; Extended Data Fig. 8b). Notably, extreme EM1 signals in the Afanasy-Nikitin Rise seamounts (~600 km from Broken Ridge) has been linked to shallow recycled continental lithosphere44, consistent with the episodic ‘spikes’ of enrichment predicted by our model (Fig. 3b).

Global implications

Taken together, our data and observations support a model in which convective removal of SCLM supplies enriched material to the suboceanic asthenosphere, explaining both the early peak and long-term decline41 in enriched components involved in mantle melting (Fig. 5a,b). We infer that this decline reflects a progressive reduction in the volume of delaminated SCLM entering the suboceanic asthenosphere (Fig. 3). This laterally propagating cratonic material reaches shallow mantle depths when the oceanic lithosphere is young and thin50. The upwelling EM1-bearing mantle undergoes decompressional melting while simultaneously metasomatizing the nascent oceanic lithosphere50.

This highly organized convective erosion of lithospheric keels (Fig. 3) is a global physical process that creates a diffuse ‘pool’ of ancient lithospheric domains in the upper mantle. This material, shaped by the complex and long-term (that is, Gyr) thermochemical51 and metasomatic52 evolution of the lithospheric roots, most closely resembles the composition of the putative EM1 mantle end member (Figs. 2a and 5a). This heterogeneous material radiated outwards from the cratonic roots during and after Gondwana break-up (Fig. 4a and Extended Data Fig. 1). This mechanism may thus provide insights into the origin and distribution of the extensive DUPAL isotope anomaly, which is linked to the EM1 reservoir1,43,53 and shows a geospatial association with Gondwana break-up zones54 (Fig. 4a and Extended Data Fig. 1). Indeed, geochemical evidence from deep xenoliths indicates that the SCLM carries DUPAL isotope characteristics55, consistent with suggestions that DUPAL is a shallow mantle feature20,56. Rather than remaining stagnant since Gondwana break-up54, DUPAL’s present-day distribution53 (Extended Data Fig. 1) may reflect a persistent flow of decoupled, highly heterogeneous SCLM from the continental roots into the suboceanic asthenosphere, perhaps reconciling the geochemical similarity between OIBs and some continental intraplate basalts57.

Our geodynamic models indicate that convective erosion of lithospheric keels can persist long after continental break-up, exerting a waning influence over time (Fig. 3b), punctuated by transient pulses of enrichment that extend even to distant parts of the oceanic plate. These findings support the view that the EM1 source taps an ancient, enriched SCLM reservoir20,21. The same ‘mantle wave’ mechanism—previously invoked to explain kimberlite volcanism9 and plateau uplift10 in cratonic settings—operates on predictable timescales, which are manifested in major seamount provinces (Figs. 2, 4 and 5 and Extended Data Figs. 7 and 8). This offers a viable, perhaps auxiliary, alternative to deep-mantle plumes in explaining Gyr-old enrichments in ocean island volcanism associated with fragmented continental margins. Given the prevalence of hydrous and carbonated phases in the SCLM9,18,20,21, this process may have strongly influenced the volatile supply to oceanic volcanoes through time, with implications for the geosphere and the deep carbon cycle.

Methods

Geodynamic models

Our thermomechanical simulations used the geodynamic tool ASPECT (Advanced Solver for Planetary Evolution, Convection, and Tectonics), a finite element code to simulate convection in Earth’s mantle and lithospheric deformation60,61,62,63,64,65. This tool was used to compute the dynamic evolution of the continental lithosphere and the asthenosphere over a ~100 Myr period (Fig. 3a,b). The software operates by solving the conservation equations of energy, mass and momentum for Earth materials experiencing viscoplastic deformation66. We apply rheologies that account for temperature-, pressure- and strain-rate-dependent flow laws and include strain weakening mechanisms9.

The models are kinematically driven by imposing velocity boundary conditions at the left and right sides. The simulation creates a rift that migrates laterally67, delaying lithospheric break-up. The asthenosphere exhibits strong rotational flow patterns due to pressure gradients beneath the rift. The steep lithospheric gradients generated by rifting lead to the EDC and Rayleigh–Taylor instabilities that migrate cratonward. We next elaborate on the model geometry, the thermomechanical set-up as well as the limitations of the model.

The model domain comprises 120 and 800 elements in the vertical and horizontal directions, respectively, and is 300 km deep as well as 2,000 km wide. Four uniform layers make up the initial distribution of material: an upper crust that is 20 km thick, a lower crust that is 15 km thick, a mantle lithosphere that is 125 km thick and an asthenosphere that is 140 km thick. We initiate rifting in a predetermined area, by defining a domain in model centre where the crust is 5 km thicker and the mantle lithosphere is 25 km thinner than in the surrounding lithosphere, which represents mobile belt conditions typical for locations where intracontinental rifts form68. Due to initial thermal equilibration, these conditions induce a thermomechanical weakness. Over a distance of 200 km, these layer thicknesses gradually transition to the ambient lithosphere. We track the evolution of the material within a 30-km-thick asthenospheric layer beneath some portions of the lithosphere as a simplified representation of the weak metasomatized lithospheric keel. A thickness of 30 km for this layer was chosen to represent the vertical extent of the thermal boundary layer (TBL), which xenolith and geotherm analyses suggest is approximately 30–35 km thick, irrespective of the total thickness of the lithosphere9. Our models assume a 160 km depth of the thermal lithosphere–asthenosphere boundary across the continent, with ~25 km thinning in the mobile belt later exploited by the rift. While this configuration does not capture all regional variations, it is consistent with inferred lithosphere–asthenosphere boundary depths beneath most kimberlites emplaced over the past 250 million years9, suggesting it is not an unreasonable approximation for our study.

The flow laws of each layer represent, respectively, the upper crust, lower crust, mantle lithosphere and asthenosphere, as wet quartzite69, wet anorthite70, dry olivine71 and wet olivine71 (see ref. 9 for thermomechanical parameters). Prior sensitivity analysis shows that varying viscosity of the lithospheric TBL and the asthenosphere within a realistic range does not have an appreciable impact on the wavelength (42–65 km) or propagation rate (14–33 km Myr−1) of Rayleigh–Taylor instabilities—the key variables of interest. Rayleigh–Taylor instabilities are primarily driven by density contrasts; viscosity variations, while influential, are not the dominant control. Nonetheless, we conducted 28 additional sensitivity experiments to ascertain how covariation in density and viscosity affects decoupling, entrainment and transport processes, along with their characteristic timescales (see below). Our model includes a piece-wise linear function to account for strain-dependent friction softening: (1) the friction coefficient linearly decreases by up to 75% between a brittle strain range of 0 and 1; (2) the friction coefficient remains constant for strains >1. Analogously, we account for viscous strain-dependent weakening via a linear reduction of the viscosity up to 75% within a range of the viscous strain between 0 and 1.

In the asthenosphere, we adopt an activation energy of 480 kJ mol−1. The impact of varying asthenospheric activation energy on the migration of instabilities and the process of convective removal has been explored in prior work9 and is now summarized. Sublithospheric viscosity, particularly its dependence on activation energy, plays a crucial role in the development of mantle instabilities. Shallow-asthenosphere viscosity is primarily governed by dislocation creep, consistent with observations of seismic anisotropy in the upper mantle. We adopt experimentally derived flow laws of wet olivine dislocation creep with an activation energy of 480 ± 40 kJ mol−1 (ref. 71). These values are well within the independently determined range of 360–540 kJ mol−1 (ref. 72). To assess model robustness, we performed additional simulations varying activation energy within experimental uncertainties while keeping all other parameters constant. Lowering the activation energy to 440 kJ mol−1 reduces viscosity in the shallow asthenosphere and TBL by approximately a factor of two. This increases the lateral propagation and migration rates of instabilities by a similar factor. Increasing the activation energy to 530 kJ mol−1 leads to a viscosity increase that prevents the formation of Rayleigh–Taylor instabilities. We conclude that dripping of metasomatized material is possible only for sufficient low viscosities of the cratonic keels (the regime threshold is examined further, as described below). If dripping takes place, however, it migrates along the base of the craton at a rate that is inversely proportional to the keel viscosity9.

We employ velocity boundary conditions with a 10 mm yr−1 extension rate. We fix the right-hand side of the model for simplicity through a free-slip boundary condition and no material inflow. However, we confirmed that, even if extension velocities are distributed symmetrically at both side boundaries, our findings remain the same. A continual input of material via the lower boundary counterbalances the material outflux through the left boundary. This influx rate through the lower boundary (1.5 mm yr−1) is derived from the ratio between horizontal and vertical model extent multiplied by the imposed divergence rate. In contrast to the lower boundary, a free surface is used at the upper boundary meaning that this boundary is free of tractions, able to distort and without any inflow or outflow of mass65.

The lateral borders are thermally insulated, and the bottom and surface temperatures are respectively maintained at 1,420 °C and 0 °C. The distribution of temperature is initially balanced along one-dimensional columns by equilibrating the temperature field accounting for the contribution of thermal boundary conditions, radiogenic heat production, heat capacity and thermal diffusivity. Here, we set the initial depth of the compositional lithosphere–asthenosphere boundary at a temperature of 1,350 °C to equal the bottom of the conductive lithosphere. In the sublithosphere domain, the initial temperature increases adiabatically with depth. We further equilibrate the entire temperature distribution of the model for 30 Myr before the start of extension to smooth the change in the thermal gradient between the lithosphere and asthenosphere.

The following model assumptions need to be taken into consideration when evaluating our findings: (1) Chemical changes, melt production and magma ascent are not explicitly taken into account as we concentrate on first-order thermomechanical processes. Specifically, we examine the distribution of ‘tracer’ material—the removed portions of the metasomatized lithospheric keel—through time and space. This material is available for melting in the asthenosphere where decompression is expected to occur beneath young, thin oceanic lithosphere. While we estimate the timescales for this SCLM material to reach the surface via convective upwelling (Extended Data Fig. 6), our ASPECT models cannot currently be implemented to resolve their chemical or melting properties. However, we do not think that the omission of melting materially weakens our main conclusions. Its primary effect—reducing viscosity in the lower lithosphere—would probably enhance, rather than hinder, the invoked delamination process. Indeed, previous studies show that viscosity reductions due to partial melting can weaken the lithosphere73. This effect, combined with density contrasts arising from temperature differences across the TBL9, would only act to augment keel removal. With regard to melting processes within the asthenosphere, further work is needed to incorporate melting into geodynamic models in a manner that balances realism with uncertainty, reflecting our incomplete understanding of these compositionally and rheologically complex natural systems.

(2) Our general modelling approach omits processes associated with mantle plumes, along-strike lithospheric heterogeneities and large-scale mantle flow patterns. This is appropriate for our set-up because we focus on the removal and lateral transport of continental keel material within the upper mantle, rather than deep mantle dynamics. A deeper domain with an open lower boundary would probably introduce additional complexities beyond the scope of our study, such as whole-mantle circulation effects, which are not required to capture the primary processes of interest. Nonetheless, we conducted further tests to explore the possible impact of a deeper model domain on the scale and spacing of Rayleigh–Taylor instabilities10, finding that these did not change appreciably (see below). Furthermore, in nature, the lateral mantle flow, or mantle wind, will vary by location, but in many cases, its motion—for example, the westward flow beneath Africa—will help transport decoupled SCLM domains into the suboceanic asthenosphere. Nonetheless, further research is needed to assess how their formation and migration interact with deeper mantle upwellings, a question beyond the scope of this study.

(3) We assume, for simplicity, that the lithosphere–asthenosphere boundary’s initial depth does not vary on a scale of a thousand kilometres. We confirmed that the presence of a sloping lithosphere–asthenosphere boundary and changes in the lithospheric thickness between models did not affect our conclusions. We also conducted experiments extending the vertical extent of the model domain to 410 km, assessing whether this change impacts the scale, spacing or speed of Rayleigh–Taylor instabilities—the primary mechanism of convective removal and transport in our models. Here, we found that the distance between two Rayleigh–Taylor instabilities does not increase proportionally to the height of the convection cell. Despite the 410-model having convection cells approximately twice as high as the reference model, the distance between instabilities—when measured at the depth of the TBL (that is, the metasomatized layer which is beige in the animation)—remains remarkably similar. The drips maintain a similar width at the level of the TBL, irrespective of whether the convection cells are large or small (that is, the mean spacings for the reference model and 410-model are 269 km and 255 km, respectively). For the models to be meaningful, the TBL just needs to be thin compared with the height of the convection cell—a criterion met in all cases described in our Article.

To assess the impact of the prescribed plate kinematics of the model, we introduced symmetric boundary conditions (Supplementary Video 1), varied the extension velocity (5 mm yr−1 and 20 mm yr−1 instead of 10 mm yr−1 in the reference model; Supplementary Videos 2 and 3) and explored the influence of time-dependent extension velocities. In the latter case, we conducted two model runs where the extension rate increases through time. We consider (1) slow divergence of 3 mm yr−1 for the first 5 Myr of rifting followed by fast divergence of 14 mm yr−1 until the end of the model run (Supplementary Video 4); and (2) slow divergence of 5 mm yr−1 for 20 Myr of rifting followed by fast divergence of 20 mm yr−1 until the end of the model run (Supplementary Video 5). Again, the key process of sequential delamination occurs in all scenarios as described in the reference model. Migration rates differ slightly from the reference model but are in full agreement with observational constraints.

Finally, we conducted 28 simulations to assess how the covariation in density and viscosity of the metasomatized lithospheric keel influence its evolution during continental rifting and break-up. In each model, only the keel’s reference density (ρ0) and activation energy—a key parameter in computing viscosity—were varied, while all other parameters remained consistent with the reference case (Fig. 3), which is indicated with the dashed rectangle in Extended Data Fig. 5. The SCLM keel density was systematically varied from 3,250 to 3,350 kg m−3, spanning a range of ±1.5% relative to the asthenosphere. Each model is shown 50 Myr after rift onset, with keel density (colour) overlain by viscosity (greyscale) to visualize both fields within a single frame (Extended Data Fig. 5). The experiments identify three distinct behavioural regimes (see ‘Geodynamic modelling of rifting and break-up’) and demonstrate that most scenarios result in lithospheric material entering the suboceanic asthenosphere, although on different timescales—an outcome that can be tested in future studies.

Quantifying the tempo of material transfer

Using simulation outputs, we quantify the amount of decoupled lithospheric material that enters into the suboceanic asthenosphere over time. To do this, we compute the vertical integral of the flow rate of decoupled metasomatized lithosphere (extracted from ASPECT using the open-source data analysis and visualization application, ParaView74). We first multiply the fraction of this material with the horizontal velocity component. We integrate this value vertically and rescale it so that the numbers correspond to the total thickness of material (that is, beige decoupled SCLM; Fig. 3) that passes through a line at a given x-location per output time step. The x-locations where measurements are made are located close to the lithospheric discontinuity at 150 km and 200 km from the COB as shown in Fig. 3a. The rescaled flow rate values are metres per 0.5 million years (the visualization output time step), which for simplicity is doubled and plotted as m Myr−1 (Fig. 3b). We also calculate the cumulative amount of this material over time (Fig. 3b). Using the flow rate values for both the 150 km and 200 km profiles, we applied a Lomb–Scargle periodogram—an algorithm commonly used to detect and characterize periodic signals in unevenly sampled data40,75,76. We perform this analysis in the open-source statistical programming language, R, using the data visualization package ggplot2 and library ‘lomb’. This approach is used to diagnose statistically significant signals at 5–6 Myr periods (Extended Data Fig. 4). We computed P values for the peak amplitude in the periodogram from the exponential distribution77.

An important consideration is whether the pulsing of decoupled SCLM (Fig. 3b) is a model artefact, although we consider this unlikely. In our models, the lithospheric keel (shown in beige in Fig. 3a) is continuous along the lithospheric root, except where it is thinned beneath the rift. It is not distributed in a manner that would introduce artificial cyclicity. Instead, our analysis indicates that pulsed outputs in our model (Fig. 3b and Extended Data Fig. 4) are related to EDC26,27 and Rayleigh-Taylor instabilities. Specifically, steep lithosphere–asthenosphere boundary gradients introduce pronounced horizontal temperature contrasts, where upwelling asthenosphere cools adjacent to the lithosphere, increasing viscosity and density. This density contrast induces gravitational ‘dripping’, which—due to the higher viscosity—occurs in discrete events (Extended Data Fig. 4).

Finally, it is important to establish how long it would take enriched material (that is, decoupled lithospheric material) to be detectable in surface volcanism, once it has first crossed into the asthenospheric mantle. This would approximate the time lag expected between full continental break-up (when enriched decoupled lithosphere enters the suboceanic asthenosphere) and EM1-type volcanism. To estimate this, we used simple Monte Carlo simulations to sample the length scales of typical convection cells forming near to the lithospheric discontinuity and maximum mantle flow velocities in our ASPECT simulations (Extended Data Fig. 6) to compute a range of lag times considered most likely (Fig. 3c,d). We plot the results as a histogram and probability density function (PDF; Fig. 3c), and as an empirical cumulative distribution function (Fig. 3d). This analysis suggests lag times ranging from 5 to 14.5 Myr, with a median of 8.0 and a mean of 8.7 Myr.

Geochemical data analysis

To test our geodynamic model, we first compiled isotopic data from the eastern Indian Ocean Seamount Province, encompassing the CHRISP8 and the IFZ41 (Fig. 4). The wider CHRISP region, where volcanoes formed nearer to the continental margins following the India–Australia break-up at ~126 Ma (Fig. 4a), exhibits strong EM1-type signatures8,41 and lacks any known deep plumes30, allowing mantle enrichments to be unequivocally linked to processes occurring along nearby continents8. The post-break-up volcanism in the CHRISP, spanning 116 Ma to 37 Ma, is well documented by Hoernle et al.8, with 26 radiometric ages and an array of Sr–Nd–Pb–Hf isotopes (Figs. 4 and 5). We exclude the youngest phase (4–4.5 Ma) from Christmas Island’s Upper Volcanic Series8 owing to its proximity (that is, relative to earlier magmatic phases; Fig. 4a) to the Sunda–Java subduction zone (Fig. 4b), where related crustal and tectonic processes have been implicated in that renewed melting phase78. The IFZ volcanoes, described by Dürkenfälden et al.41, include five radiometric ages and a comparable isotopic dataset. We reconstructed the locations of these sites at 50 Ma (Fig. 4a) using the open-source plate-tectonic software GPlates (https://www.gplates.org/).

Many data points in our compilation originate from broadly the same borehole or region (Extended Data Fig. 1). To mitigate sampling bias, we applied weighted bootstrap resampling following the procedure outlined by Keller and Schoene79 using

where n is the number of original observations (that is, samples in the compilation), z is the spatial location, t is the radiometric age of the rock and (a, b) are the normalization coefficients. For the latter, we apply a distance coefficient a = 100 km to account for closely spaced drilling sites, and a time coefficient b = 5 Myr, which exceeds the typical age uncertainty of the samples.

We performed 1,000 iterations, each involving weighted sampling of n points with replacement. We then calculate regression parameters for each sample set. The resulting linear regressions and corresponding r2 values are shown in Fig. 5b,c. This provides an estimate of uncertainty in the relationship between isotope ratio and age.

For a comparison exercise, we also compiled isotopic data from oceanic basalts geographically spanning the Broken Ridge, Ninety East Ridge and Kerguelen Plateau in the Indian Ocean (Extended Data Fig. 1). These volcanoes have been heavily sampled by ocean drilling expeditions, providing a reasonably continuous, well-dated sequence of ocean island magmatism from 120 to 0 Ma (Extended Data Fig. 8). We also studied contemporaneous kimberlites from southern Africa and India (Fig. 2a). The original positions of these sites are shown in Extended Data Fig. 8a, reconstructed using GPlates.

For the time series analysis, we used samples with well-accepted radiometric ages acquired from several International Ocean Discovery Program expeditions (Supplementary Tables 1–3). The data are summarized in Extended Data Fig. 8b (Kerguelen), which shows the variation in (206Pb/204Pb)i over time, coloured by ϵNdi, where

where CHUR refers to the isotopic ratio of the Chondritic Uniform Reservoir.

In a separate analysis investigating the onset of volcanism at Walvis Ridge and its relation to contemporaneous kimberlite volcanism in Africa, we performed CPR80 to detect whether any step changes are present in the isotope datasets for Walvis Ridge7,37 (Fig. 2d). This approach, deployed in the numeric computing platform, MATLAB, applies an iterative algorithm involving binary partitioning by marginal likelihood and conjugate priors to identify an unknown number of change points80. In the case that a marginal likelihood favours a change-point model, the CPR algorithm defines a change point and two-sigma uncertainty bounds of the two averages before and after the change point80. Previously, we used this approach to show a change point in (87Sr/86Sr)i and ϵNdi in southern African kimberlites occurs at 117 and 114 Ma (Fig. 2b–d), which coincides with inferred delamination of the lithospheric keel of the Kaapvaal craton9. Using the same procedure, we identified a step change in ϵNdi at the Walvis Ridge occurs between 112 Ma and 107 Ma (Fig. 2d), >2 Myr after the recorded onset of volcanism there (Fig. 2e).

Data availability

All data related to this article can be found in Supplementary Tables 1–3 and are also available via figshare at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.30086716 (ref. 81). Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

The input file, custom source code and ASPECT installation details for the thermomechanical simulations used in this study are available via Zenodo at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7825780 (ref. 64).

References

Zindler, A. & Hart, S. Chemical geodynamics. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 14, 493–571 (1986).

Jackson, M. G. & Dasgupta, R. Compositions of HIMU, EM1, and EM2 from global trends between radiogenic isotopes and major elements in ocean island basalts. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 276, 175–186 (2008).

Salters, V. J. M. & Sachi-Kocher, A. An ancient metasomatic source for the Walvis Ridge basalts. Chem. Geol. 273, 151–167 (2010).

Turner, S. J., Langmuir, C. H., Dungan, M. A. & Escrig, S. The importance of mantle wedge heterogeneity to subduction zone magmatism and the origin of EM1. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 472, 216–228 (2017).

Stracke, A., Hofmann, A. W. & Hart, S. R. FOZO, HIMU, and the rest of the mantle zoo. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 6, Q05007 (2005).

Wang, X.-J. et al. Mantle transition zone-derived EM1 component beneath NE China: geochemical evidence from Cenozoic potassic basalts. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 465, 16–28 (2017).

Hoernle, K. et al. How and when plume zonation appeared during the 132 Myr evolution of the Tristan Hotspot. Nat. Commun. 6, 7799 (2015).

Hoernle, K. et al. Origin of Indian Ocean Seamount Province by shallow recycling of continental lithosphere. Nat. Geosci. 4, 883–887 (2011).

Gernon, T. M. et al. Rift-induced disruption of cratonic keels drives kimberlite volcanism. Nature 620, 344–350 (2023).

Gernon, T. M. et al. Coevolution of craton margins and interiors during continental break-up. Nature 632, 327–335 (2024).

Jackson, M. G. & Macdonald, F. A. Hemispheric geochemical dichotomy of the mantle is a legacy of austral supercontinent assembly and onset of deep continental crust subduction. AGU Adv. 3, e2022AV000664 (2022).

Homrighausen, S. et al. Paired EMI-HIMU hotspots in the South Atlantic—starting plume heads trigger compositionally distinct secondary plumes? Sci. Adv. 6, eaba0282 (2022).

Ussami, N., Chaves, CarlosA. M., Marques, L. S. & Ernesto, M. Origin of the Rio Grande Rise–Walvis Ridge reviewed integrating palaeogeographic reconstruction, isotope geochemistry and flexural modelling. Geol. Soc. Lond. Special Publ. 369, 129–146 (2013).

White, W. M. Probing the Earth’s deep interior through geochemistry. Geochem. Perspect. 4, 95–96 (2015).

Pilet, S., Hernandez, J., Sylvester, P. & Poujol, M. The metasomatic alternative for ocean island basalt chemical heterogeneity. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 236, 148–166 (2005).

Foley, S. F. & Fischer, T. P. An essential role for continental rifts and lithosphere in the deep carbon cycle. Nat. Geosci. 10, 897–902 (2017).

Guimarães, A. R., Fitton, J. G., Kirstein, L. A. & Barfod, D. N. Contemporaneous intraplate magmatism on conjugate South Atlantic margins: a hotspot conundrum. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 536, 116147 (2020).

Gernon, T. M. et al. Transient mobilization of subcrustal carbon coincident with Palaeocene–Eocene Thermal Maximum. Nat. Geosci. 15, 573–579 (2022).

Elkins-Tanton, L. T. Continental magmatism, volatile recycling, and a heterogeneous mantle caused by lithospheric gravitational instabilities. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 112, B03405 (2007).

Hawkesworth, C. J., Mantovani, M. S. M., Taylor, P. N. & Palacz, Z. Evidence from the Parana of south Brazil for a continental contribution to Dupal basalts. Nature 322, 356–359 (1986).

McKenzie, D. & O’Nions, R. K. The source regions of ocean island basalts. J. Petrol. 36, 133–159 (1995).

Fitzpayne, A. et al. Progressive metasomatism of the mantle by kimberlite melts: Sr–Nd–Hf–Pb isotope compositions of MARID and PIC minerals. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 509, 15–26 (2019).

Huismans, R. & Beaumont, C. Depth-dependent extension, two-stage break-up and cratonic underplating at rifted margins. Nature 473, 74–78 (2011).

Hanan, B. B. & Schilling, J.-G. The dynamic evolution of the Iceland mantle plume: the lead isotope perspective. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 151, 43–60 (1997).

Liu, C.-Z. et al. Archean cratonic mantle recycled at a mid-ocean ridge. Sci. Adv. 8, eabn6749 (2022).

King, S. D. & Anderson, D. L. Edge-driven convection. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 160, 289–296 (1998).

King, S. D. & Ritsema, J. African hot spot volcanism: small-scale convection in the upper mantle beneath cratons. Science 290, 1137–1140 (2000).

Manjón-Cabeza Córdoba, A. & Ballmer, M. D. The role of edge-driven convection in the generation of volcanism—Part 1: a 2D systematic study. Solid Earth 12, 613–632 (2021).

Anderson, D. L. The persistent mantle plume myth. Aust. J. Earth Sci. 60, 657–673 (2013).

Bao, X., Lithgow-Bertelloni, C. R., Jackson, M. G. & Romanowicz, B. On the relative temperatures of Earth’s volcanic hotspots and mid-ocean ridges. Science 375, 57–61 (2022).

Raddick, M. J., Parmentier, E. M. & Scheirer, D. S. Buoyant decompression melting: a possible mechanism for intraplate volcanism. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 107, 2228 (2002).

Tappe, S., Smart, K., Torsvik, T., Massuyeau, M. & de Wit, M. Geodynamics of kimberlites on a cooling Earth: clues to plate tectonic evolution and deep volatile cycles. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 484, 1–14 (2018).

Nowell, G. M. et al. Hf isotope systematics of kimberlites and their megacrysts: new constraints on their source regions. J. Petrol. 45, 1583–1612 (2004).

Woodhead, J., Hergt, J., Phillips, D. & Paton, C. African kimberlites revisited: in situ Sr-isotope analysis of groundmass perovskite. Lithos 112, 311–317 (2009).

Smith, C. B. Pb, Sr and Nd isotopic evidence for sources of southern African Cretaceous kimberlites. Nature 304, 51–54 (1983).

Hu, J. et al. Modification of the Western Gondwana craton by plume–lithosphere interaction. Nat. Geosci. 11, 203–210 (2018).

Homrighausen, S. et al. New age and geochemical data from the Walvis Ridge: the temporal and spatial diversity of South Atlantic intraplate volcanism and its possible origin. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 245, 16–34 (2019).

Brune, S., Williams, S. E., Butterworth, N. P. & Müller, R. D. Abrupt plate accelerations shape rifted continental margins. Nature 536, 201–204 (2016).

Rohde, J. et al. 70 ma chemical zonation of the Tristan–Gough hotspot track. Geology 41, 335–338 (2013).

VanderPlas, J. T. Understanding the Lomb–Scargle periodogram. Astrophys. J. Suppl. Ser. 236, 1–26 (2018).

Dürkefälden, A. et al. Geochemical and temporal evolution of Indian MORB mantle revealed by the Investigator Ridge in the NE Indian Ocean. Gondwana Res. 134, 347–364 (2024).

Homrighausen, S. et al. Evidence for compositionally distinct upper mantle plumelets since the early history of the Tristan–Gough hotspot. Nat. Commun. 14, 3908 (2023).

Dupré, B. & Allègre, C. J. Pb–Sr isotope variation in Indian Ocean basalts and mixing phenomena. Nature 303, 142–146 (1983).

Mahoney, J. J., White, W. M., Upton, B. G. J., Neal, C. R. & Scrutton, R. A. Beyond EM-1: Lavas from Afanasy-Nikitin Rise and the Crozet Archipelago, Indian Ocean. Geology 24, 615–618 (1996).

Borisova, A. Y., Belyatsky, B. V., Portnyagin, M. V. & Sushchevskaya, N. M. Petrogenesis of olivine-phyric basalts from the Aphanasey Nikitin Rise: evidence for contamination by cratonic lower continental crust. J. Petrol. 42, 277–319 (2001).

Hanan, B. B., Blichert-Toft, J., Pyle, D. G. & Christie, D. M. Contrasting origins of the upper mantle revealed by hafnium and lead isotopes from the Southeast Indian Ridge. Nature 432, 91–94 (2004).

Escrig, S., Capmas, F., Dupré, B. & Allègre, C. J. Osmium isotopic constraints on the nature of the DUPAL anomaly from indian mid-ocean-ridge basalts. Nature 431, 59–63 (2004).

Homrighausen, S., Hoernle, K., Wartho, J. A., Hauff, F. & Werner, R. Do the 85 °E Ridge and Conrad Rise form a hotspot track crossing the Indian Ocean? Lithos 398-399, 106234 (2021).

Müller, R. D. et al. A global plate model including lithospheric deformation along major rifts and orogens since the Triassic. Tectonics 38, 1884–1907 (2019).

Humphreys, E. R. & Niu, Y. On the composition of ocean island basalts (OIB): the effects of lithospheric thickness variation and mantle metasomatism. Lithos 112, 118–136 (2009).

Capitanio, F. A., Nebel, O. & Cawood, P. A. Thermochemical lithosphere differentiation and the origin of cratonic mantle. Nature 588, 89–94 (2020).

Pearson, D. G. et al. Deep continental roots and cratons. Nature 596, 199–210 (2021).

Hart, S. R. A large-scale isotope anomaly in the Southern Hemisphere mantle. Nature 309, 753–757 (1984).

De Witt, M., Jeffery, M., Bergh, H. & Nicolaysen, L. Geological Map of Sectors of Gondwana Reconstructed to Their Disposition (American Association of Petroleum Geologists, 1988).

Mazzucchelli, M. et al. Origin of the DUPAL anomaly in mantle xenoliths of Patagonia (Argentina) and geodynamic consequences. Lithos 248-251, 257–271 (2016).

Goldstein, S. L. et al. Origin of a ‘Southern Hemisphere’ geochemical signature in the Arctic upper mantle. Nature 453, 89–93 (2008).

Fitton, J. G. The OIB Paradox. in Plates, Plumes and Planetary Processes Vol. 430 (eds Foulger, G. R. & Jurdy, D. M.) 387–412 (Geological Society of America, 2007).

Kumar, A., Dayal, A. M. & Padmakumari, V. M. Kimberlite from Rajmahal magmatic province: Sr–Nd–Pb isotopic evidence for Kerguelen plume derived magmas. Geophysical Res. Lett. 30, 2053 (2003).

Rollinson, H. & Pease, V. Using Geochemical Data 2nd edn (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2021).

Kronbichler, M., Heister, T. & Bangerth, W. High accuracy mantle convection simulation through modern numerical methods. Geophys. J. Int. 191, 12–29 (2012).

Bangerth, W. & Heister, T. Aspect v1.4.0. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.164192 (2016).

Bangerth, W. et al. ASPECT: Advanced Solver for Problems in Earth’s ConvecTion, User Manual. figshare https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.4865333.v8 (2021).

Heister, T., Dannberg, J., Gassmöller, R. & Bangerth, W. High accuracy mantle convection simulation through modern numerical methods–II: realistic models and problems. Geophys. J. Int. 210, 833–851 (2017).

Glerum, A. Input file, custom source code and ASPECT installation details for the thermomechanical simulations in Gernon et al. 2023. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8185948, (2023).

Rose, I., Buffett, B. & Heister, T. Stability and accuracy of free surface time integration in viscous flows. Phys. Earth Planet. Interiors 262, 90–100 (2017).

Glerum, A., Thieulot, C., Fraters, M., Blom, C. & Spakman, W. Nonlinear viscoplasticity in ASPECT: benchmarking and applications to subduction. Solid Earth 9, 267–294 (2018).

Brune, S., Heine, C., Pérez-Gussinyé, M. & Sobolev, S. V. Rift migration explains continental margin asymmetry and crustal hyper-extension. Nat. Commun. 5, 4014 (2014).

Pasyanos, M. E., Masters, T. G., Laske, G. & Ma, Z. LITHO1.0: an updated crust and lithospheric model of the Earth. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 119, 2153–2173 (2014).

Rutter, E. H. & Brodie, K. H. Experimental grain size-sensitive flow of hot-pressed Brazilian quartz aggregates. J. Struct. Geol. 26, 2011–2023 (2004).

Rybacki, E., Gottschalk, M., Wirth, R. & Dresen, G. Influence of water fugacity and activation volume on the flow properties of fine-grained anorthite aggregates. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 111, B03203 (2006).

Hirth, G. & Kohlstedt, D. in Inside the Subduction Factory (ed. Eiler, J.) 83–105 (American Geophysical Union, (2004).

van Hunen, J., Zhong, S., Shapiro, N. M. & Ritzwoller, M. H. New evidence for dislocation creep from 3-D geodynamic modeling of the Pacific upper mantle structure. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 238, 146–155 (2005).

Gerya, T. Large-scale-long-term strength of the lithosphere: new theory and applications. Petrology 32, 128–141 (2024).

Ahrens, J., Geveci, B. & Law, C. ParaView: An End-User Tool for Large Data Visualization (Elsevier, 2005).

Lomb, N. R. Least-squares frequency analysis of unequally spaced data. Astrophys. Space Science 39, 447–462 (1976).

Scargle, J. D. Studies in astronomical time series analysis. II. Statistical aspects of spectral analysis of unevenly spaced data. Astrophys. J. 263, 835–853 (1982).

Press, W. H., Teukolsky, S. A., Vetterling, S. T. & Flannery, B. P. Numerical Recipes in C: The Art of Scientific Computing 2nd edn (Cambridge Univ. Press, 1994).

Taneja, R. et al. 40Ar/39Ar geochronology and the paleoposition of Christmas Island (Australia), Northeast Indian Ocean. Gondwana Res. 28, 391–406 (2015).

Keller, C. B. & Schoene, B. Statistical geochemistry reveals disruption in secular lithospheric evolution about 2.5 Gyr ago. Nature 485, 490–493 (2012).

Jensen, G. Closed-form estimation of multiple change-point models. PeerJ Preprints 1, e90v3 (2013).

Gernon, T. Data associated with the paper ‘Enriched mantle generated through persistent convective erosion of continental roots’. figshare https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.30086716 (2025).

Hasterok, D. et al. New maps of global geological provinces and tectonic plates. Earth Sci. Rev. 231, 104069 (2022).

da Silva, B. V. et al. Evolution of the Southwestern Angolan Margin: episodic burial and exhumation is more realistic than long-term denudation. Int. J. Earth Sci. 108, 89–113 (2019).

Margirier, A. et al. Climate control on Early Cenozoic denudation of the Namibian margin as deduced from new thermochronological constraints. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 527, 115779 (2019).

Baby, G. Mouvements verticaux des marges passives d’Afrique australe depuis 130 Ma, étude couplée: stratigraphie de bassin – analyse des formes du relief. PhD thesis, Université de Rennes (2017).

Poudjom Djomani, Y. H., O’Reilly, S. Y., Griffin, W. L. & Morgan, P. The density structure of subcontinental lithosphere through time. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 184, 605–621 (2001).

Lee, C.-T. A., Luffi, P. & Chin, E. J. Building and destroying continental mantle. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 39, 59–90 (2011).

Furman, T., Nelson, W. R. & Elkins, L. T. Evolution of the East African rift: drip magmatism, lithospheric thinning and mafic volcanism. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 185, 418–434 (2016).

Steinberger, B. Topography caused by mantle density variations: observation-based estimates and models derived from tomography and lithosphere thickness. Geophys. J. Int. 205, 604–621 (2016).

Wang, Y., Liu, L. & Zhou, Q. Topography and gravity reveal denser cratonic lithospheric mantle than previously thought. Geophys. Res. Lett. 49, e2021GL096844 (2022).

Acknowledgements

T.M.G. and T.K.H. gratefully acknowledge funding from the WoodNext Foundation, a donor-advised fund programme. S.B. is funded by the European Research Council (ERC) (EMERGE; award number 101087245). We thank the Computational Infrastructure for Geodynamics (https://geodynamics.org/) which is funded by the National Science Foundation under award EAR-0949446 and EAR- 1550901 for supporting the development of ASPECT. We acknowledge the computing time granted by the Resource Allocation Board and provided on the supercomputers Lise at NHR@ZIB and Emmy at NHR-Nord@Göttingen as part of the NHR infrastructure. The calculations for this research were conducted with computing resources under the projects bbp00039 and bbp00064. The maps shown in Fig. 4a and Extended Data Fig. 8a were plotted with the open-source plate tectonic application software GPlates (https://www.gplates.org/), which is licensed for distribution under a GNU General Public License, and the open source spatial mapping software QGIS. In Fig. 4, the the underlying bathymetric data were obtained from GeoMapApp v. 3.7.4 (https://www.geomapapp.org/), which incorporates topographic relief from the Global Multi-Resolution Topography (GMRT) synthesis. For the purpose of open access, a CC BY public copyright licence has been applied to any Author Accepted Manuscript version arising from this submission.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization and project administration: T.M.G.; conceptualization of geodynamic models: S.B. and A.G.; methodology, formal analysis, and software: T.K.H., T.M.G., E.J.W. (R), S.B., A.G. (ASPECT, Paraview) and C.J.S. (CPR); investigation: T.K.H., T.M.G., E.J.W., S.B., A.G., C.J.S. and M.R.P.; funding acquisition: T.M.G.; visualization: T.K.H., S.B., A.G. and T.M.G.; writing—original draft: T.M.G.; writing—review and editing: all authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Geoscience thanks Kaj Hoernle and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editor: Alison Hunt, in collaboration with the Nature Geoscience team.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Extended Data Fig. 1 Spatial distribution of the DUPAL isotope anomaly.

a, Global map showing the distribution of the DUPAL anomaly as expressed by ΔSr from Hart (1984)53; studied locations (diamond symbols) are listed with coordinates in Supplementary Tables 1-4; cratons and plate boundaries are from Hasterok et al. (2022)82; b, Detailed view (see a) of the South Atlantic region and location of samples from Walvis Ridge in relation to Africa (DUPAL features from Hart (1984)53 and Mazzucchelli et al. (2016)55); c, Detailed view (see a) showing the Indian Ocean region, including the Christmas Island Seamount Province (CHRISP) and the Investigator Fracture Zone (Fig. 4), and the Kerguelen Plateau, which includes Broken Ridge and the Ninety East Ridge (note these originally formed a contiguous volcanic province, the original extent of which is reconstructed in Extended Data Fig. 8a). Maps created using QGIS software under a GNU General Public License. Plate shapefiles adapted from ref. 82.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Tectonism, volcanism, and uplift of continental margins near the Walvis Ridge.

a, Thermal history of the SW Angolan margin (see Extended Data Fig. 1a) from apatite fission-track and (U-Th)/He data83 showing cooling onset shortly after 110 Ma; b, Thermal history of part of the western Namibian margin (Extended Data Fig. 1b), based on a low-elevation sample from the Brandberg Massif, deduced using apatite (U-Th-Sm)/He dating and apatite fission track data84, showing a phase of rapid cooling thought to be associated with continental break-up (~ 10∘C/Myr or 400 m Myr−1, assuming a geothermal gradient of 25∘C km−1); c, Sediment accumulation history of the Walvis Basin (from ref. 85); note sediment accumulation increases several Myr after break-up, coinciding with uplift and denudation of continental margins (see a and b). d, Full rift velocity of the Central South Atlantic near the Walvis Ridge (from ref. 38); also shown is the frequency of dated volcanics at Walvis Ridge from Hoernle et al. (2015)7 and Homrighausen et al. (2019)37.

Extended Data Fig. 3 Flux of removed SCLM into the (proto)oceanic asthenosphere under sustained slow extension.

a, Flow rate of decoupled lithospheric material crossing a transect 200 km inboard of the COB into the sub-oceanic asthenosphere (SOA) over time, using a slow extension rate of 5 mm yr−1. b, Cumulative frequency of SCLM addition to the SOA for the model output in a, showing a declining growth rate over time. This sustained low-velocity divergence scenario is considered unlikely, as most rift systems–such as the South Atlantic–exhibit a marked acceleration in divergence rate after ~ 20 Myr due to feedbacks between rift weakening and extension38.

Extended Data Fig. 4 Periodicity of SCLM transport into the oceanic asthenosphere.

Lomb-Scargle periodograms (see Methods) showing pulsing of decoupled EM1-type material on 5-6 Myr periods. The upper and lower plots were constructed 200 km and 150 km, respectively, from the COB (for context, refer to Fig. 3a–b).

Extended Data Fig. 5 Regime diagram showing the influence of metasomatized SCLM keel density and viscosity on instabilitymigration.

Results from 28 numerical experiments illustrate the state of the metasomatized keel (coloured zone) 50 Myr after rift onset, for different combinations of density and activation energy of dislocation creep of the keel. The activation energy is a key parameter in defining the viscosity of the metasomatized layer. The temperature-dependent density is shown in cold/warm colours overlain with viscosity in a transparent grey scale. Density and viscosity are changed only within the metasomatized layer; all other parameters match the reference model (demarcated with the dashed rectangle). The activation energy is varied within the uncertainty of experimental bounds71, a range that is notably included in the permissible spectrum based on independent numerical modelling72. The density of continental keels is not well known (for example, refs. 85,86) and is dependent on the degree of metasomatism87,88. Here, we varied metasomatized keel densities across a wide range that is arguably larger than inferred lithospheric excess densities of 0.2-0.4% (ref. 89) and 0.5-1.2% (ref. 90) Increasing density accelerates instability migration, consistent with analytical predictions9, while increasing viscosity (that is, increasing activation energy) slows down the migration.

Extended Data Fig. 6 Characteristic length scales of simulated convection cells.

a, Snapshot of a thermo-mechanical simulation run in ASPECT featuring an edge-driven convection cell; six arrows show representative flow pathways, the length-scales of which are given in the accompanying table; these measurements inform a sampled range of 350 to 500 km used in our Monte Carlo simulations to capture this variability. b, Statistical output showing how maximum velocities vary through the entire model run (see the Methods for details on the thermo-mechanical simulations). These ranges of length-scales and velocities of convective flow were used to estimate times taken for material entrained into these cells beneath the lithospheric discontinuity (shown) to reach the base of the oceanic plate.

Extended Data Fig. 7 Isotopic evolution of the Christmas Island Seamount Province and Investigator Fracture Zone through time.

a, Temporal variation in (208Pb/204Pb)i over time, coloured by ϵNdi (data are from refs. 8,41); the indicative field of EM1 shown in pink is from refs. 41,42. b, Temporal variation in (207Pb/204Pb)i over time, again coloured by ϵNdi. Linear regressions (n=1,000 from weighted bootstrap resampling procedure; Methods) are shown in blue, and statistical measures of the modelled and raw data are provided at the top of the plots (data and references are provided in Supplementary Data 1).

Extended Data Fig. 8 Geochemical evolution of other EM-type volcanism in time and space.

a, Plate reconstruction at 90 Ma showing the original distribution of other studied locations; estimated outer limit of DUPAL isotope anomaly is adapted from ref. 54; b, (206Pb/204Pb)i of volcanics from the Kerguelen Plateau and originally contiguous regions (see a) plotted over time and coloured by ϵNdi. Data sources are listed in Supplementary Tables 2-3. The EM1 field (from ref. 1) is shown in pink. Higher (206Pb/204Pb)i commonly corresponds to higher ϵNdi (where ϵNdi > 0 indicates depleted mantle, and ϵNdi < 0 indicates enriched mantle compositions; Fig. 2). Linear regressions (n=1,000) from a weighted bootstrap resampling procedure (see Methods) are shown in blue. Panel a was created using GPlates v. 2.3.0 under a CC BY 3.0 license and plotted using QGIS software under a GNUGeneral Public license.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Video 1

Video of ASPECT thermo-mechanical simulations of continental rifting and break-up, where extension velocities are applied symmetrically at both side boundaries. Sequential delamination occurs as described in the reference model. The logarithmic strain rates and asthenospheric temperatures are displayed (see key).

Supplementary Video 2

Video of ASPECT thermomechanical simulations of continental rifting and break-up under a slow extension regime (5 mm yr−1), showing the formation and sequential propagation of Rayleigh–Taylor instabilities along the lithospheric keel. The logarithmic strain rates and asthenospheric temperatures are displayed (see key).

Supplementary Video 3

Video of ASPECT thermomechanical simulations of continental rifting and break-up under a fast extension regime (20 mm yr−1), showing the formation and sequential propagation of Rayleigh–Taylor instabilities along the lithospheric keel. The logarithmic strain rates and asthenospheric temperatures are displayed (see key).

Supplementary Video 4

Video of ASPECT thermomechanical simulations of continental rifting and break-up showing the effects of time-dependent extension velocities. This involves slow divergence of 3 mm yr−1 for the first 5 Myr of rifting followed by fast divergence of 14 mm yr−1 until the end of the model run.

Supplementary Video 5

Video of ASPECT thermomechanical simulations of continental rifting and break-up showing the effects of time-dependent extension velocities. This involves slow divergence of 5 mm yr−1 for 20 Myr of rifting followed by fast divergence of 20 mm yr−1 until the end of the model run.

Supplementary Table 2

Compilation of isotope data for volcanic rocks from Kerguelen Plateau, Broken Ridge, St Paul and Amsterdam Island, Ninety East Ridge and India.

Supplementary Table 3

Compilation of isotope data for Kerguelen Plateau volcanics.

Source data

Source Data Fig. 2

Source data (isotopic and age data).

Source Data Fig. 3

Geodynamic model data outputs.

Source Data Fig. 4

Geospatial data used to plot maps.

Source Data Fig. 5

Note on Fig. 5 data directing reader to Supplementary Table 1.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 1

Geospatial data used to plot the map.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 2

Various datasets including sedimentation rate data, rift velocity data and volcanism age data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 3

Geodynamic model data outputs.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 4

Geodynamic model data outputs.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 6

Geodynamic model data outputs.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 7

Note on Extended Data Fig. 7 data directing reader to Supplementary Table 1.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 8

Note on Extended Data Fig. 8 data directing reader to Supplementary Tables 2 and 3.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gernon, T.M., Brune, S., Hincks, T.K. et al. Enriched mantle generated through persistent convective erosion of continental roots. Nat. Geosci. 18, 1311–1318 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41561-025-01843-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41561-025-01843-9