Abstract

Iron is the primary limiting nutrient for phytoplankton growth, and consequently CO2 drawdown, in the Southern Ocean. A recurring phytoplankton bloom above the Australian Antarctic Ridge was recently attributed to hydrothermally sourced iron. Here we examine satellite remote-sensing estimates of net primary production, earthquake location catalogues and Lagrangian plume modelling of particle trajectories in surface ocean currents to show that interannual variability in net primary production is related to seismicity and the advective spread of downstream surface waters. By spatially decomposing the relationship between seismicity, advective spread and net primary production, we demonstrate that net primary production at the surface, above the hydrothermal vents, can be predicted by elevated seismicity in the months before the growing season. Farther from the vents, greater advective spread reduces net primary production. We hypothesize that the connection between earthquakes and net primary production is mediated by the link between seismicity and hydrothermal emissions while advective spread controls the dilution of entrained iron; however, the physical mechanism behind the rapid surfacing of hydrothermal iron is still unknown. These findings challenge prevailing views on how geophysical processes influence ocean primary production.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$32.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $21.58 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

All data used in this study can be found in the Stanford Digital Repository at https://doi.org/10.25740/yc804kn7989 (ref. 69).

Code availability

No custom code central to the conclusions of this study was developed. All analyses rely on standard statistical and arithmetic methods. The net primary production53 and Lagrangian particle modelling57 has been published elsewhere and is available from the original authors and is not redistributed here.

References

Marinov, I., Gnanadesikan, A., Toggweiler, J. R. & Sarmiento, J. L. The Southern Ocean biogeochemical divide. Nature 441, 964–967 (2006).

Boyd, P. W. et al. Mesoscale iron enrichment experiments 1993–2005: synthesis and future directions. Science 315, 612–617 (2007).

de Baar, H. J. W. et al. On iron limitation of the Southern Ocean: experimental observations in the Weddell and Scotia seas. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 65, 105–122 (1990).

Martin, J. H., Gordon, R. M. & Fitzwater, S. E. Iron in Antarctic waters. Nature 345, 156–158 (1990).

Tagliabue, A. et al. Hydrothermal contribution to the oceanic dissolved iron inventory. Nat. Geosci. 3, 252–256 (2010).

Tagliabue, A. & Resing, J. Impact of hydrothermalism on the ocean iron cycle. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. A 374, 20150291 (2016).

Ardyna, M. et al. Hydrothermal vents trigger massive phytoplankton blooms in the Southern Ocean. Nat. Commun. 10, 2451 (2019).

Schine, C. M. S. et al. Massive Southern Ocean phytoplankton bloom fed by iron of possible hydrothermal origin. Nat. Commun. 12, 1211 (2021).

Moreau, S. et al. Wind-driven upwelling of iron sustains dense blooms and food webs in the eastern Weddell Gyre. Nat. Commun. 14, 1303 (2023).

Hahm, D. et al. First hydrothermal discoveries on the Australian–Antarctic Ridge: discharge sites, plume chemistry, and vent organisms. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 16, 3061–3075 (2015).

Arrigo, K. R., van Dijken, G. L. & Strong, A. L. Environmental controls of marine productivity hot spots around Antarctica. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 120, 5545–5565 (2015).

Cann, J. & Strens, M. Modeling periodic megaplume emission by black smoker systems. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 94, 12227–12237 (1989).

Cowen, J. P., Baker, E T. & Embley, R. W. in The Subseafloor Biosphere at Mid-Ocean Ridges (eds Wilcock, W. S. D. et al.) 227–243 (AGU, 2004).

Wilcock, W. S. et al. The recent volcanic history of Axial Seamount: geophysical insights into past eruption dynamics with an eye toward enhanced observations of future eruptions. Oceanography 31, 114–123 (2018).

Mittal, T. & Delbridge, B. Detection of the 2012 Havre submarine eruption plume using Argo floats and its implications for ocean dynamics. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 511, 105–116 (2019).

Baker, E. T., Fox, C. G. & Cowen, J. P. In situ observations of the onset of hydrothermal discharge during the 1998 Submarine Eruption of Axial Volcano, Juan de Fuca Ridge. Geophys. Res. Lett. 26, 3445–3448 (1999).

Feely, R. et al. Chemical variations of hydrothermal particles in the 1996 Gorda Ridge Event and chronic plumes. Deep Sea Res. 2 45, 2637–2664 (1998).

Buck, N. J., Resing, J. A., Baker, E. T. & Lupton, J. E. Chemical fluxes from a recently erupted shallow submarine volcano on the Mariana Arc. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 19, 1660–1673 (2018).

Hensen, C. et al. Marine transform faults and fracture zones: a joint perspective integrating seismicity, fluid flow and life. Front. Earth Sci. 7, 39 (2019).

Seropian, G., Kennedy, B. M., Walter, T. R., Ichihara, M. & Jolly, A. D. A review framework of how earthquakes trigger volcanic eruptions. Nat. Commun. 12, 1004 (2021).

Coumou, D., Driesner, T., Geiger, S., Heinrich, C. A. & Matthäi, S. The dynamics of mid-ocean ridge hydrothermal systems: splitting plumes and fluctuating vent temperatures. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 245, 218–231 (2006).

Resing, J. A., Feely, R. A., Massoth, G. J. & Baker, E. T. The water-column chemical signature after the 1998 eruption of Axial Volcano. Geophys. Res. Lett. 26, 3645–3648 (1999).

Massoth, G. J. et al. Manganese and iron in hydrothermal plumes resulting from the 1996 Gorda Ridge Event. Deep Sea Res. 2 45, 2683–2712 (1998).

Geoffroy, L. et al. Hydrothermal fluid flow triggered by an earthquake in Iceland. Commun. Earth Environ. 3, 54 (2022).

Dziak, R. P., Chadwick, W. W., Fox, C. G. & Embley, R. W. Hydrothermal temperature changes at the southern Juan de Fuca Ridge associated with MW 6.2 Blanco Transform earthquake. Geology 31, 119–122 (2003).

Fornari, D. et al. Time-series temperature measurements at high-temperature hydrothermal vents, East Pacific Rise 9°49′–51′ N: evidence for monitoring a crustal cracking event. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 160, 419–431 (1998).

Johnson, H. P. et al. Earthquake-induced changes in a hydrothermal system on the Juan de Fuca mid-ocean ridge. Nature 407, 174–177 (2000).

Okubo, A. Oceanic diffusion diagrams. Deep Sea Res. 18, 789–802 (1971).

Sunda, W. G. & Huntsman, S. A. Interrelated influence of iron, light and cell size on marine phytoplankton growth. Nature 390, 389–392 (1997).

Timmermans, K. R., van der Wagt, B. & de Baar, H. J. Growth rates, half-saturation constants, and silicate, nitrate, and phosphate depletion in relation to iron availability of four large, open-ocean diatoms from the Southern Ocean. Limnol. Oceanogr. 49, 2141–2151 (2004).

Di Iorio, D. et al. Measurements and models of heat flux and plumes from hydrothermal discharges near the deep seafloor. Oceanography 25, 168–179 (2012).

Bonnet, S. et al. Natural iron fertilization by shallow hydrothermal sources fuels diazotroph blooms in the ocean. Science 380, 812–817 (2023).

Speer, K. G. Thermocline penetration by buoyant plumes. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. A 355, 443–458 (1997).

Lavelle, J., Di Iorio, D. & Rona, P. A turbulent convection model with an observational context for a deep-sea hydrothermal plume in a time-variable cross flow. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 118, 6145–6160 (2013).

Tagliabue, A. Constraining the contribution of hydrothermal iron to Southern Ocean export production using deep ocean iron observations. Front. Mar. Sci. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2022.754517 (2022).

Jenkins, W. J. Using excess 3He to estimate Southern Ocean upwelling time scales. Geophys. Res. Lett. 47, e2020GL087266 (2020).

Birchill, A. J. et al. Pathways and timescales of Southern Ocean hydrothermal iron and manganese transport. Commun. Earth Environ. 5, 413 (2024).

Thomson, R. E., Subbotina, M. M. & Anisimov, M. V. Numerical simulation of hydrothermal vent-induced circulation at Endeavour Ridge. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 110, C01004 (2005).

Xu, G. & German, C. R. Dispersion of deep-sea hydrothermal plumes at the Endeavour Segment of the Juan de Fuca Ridge: a multiscale numerical study. Front. Mar. Sci. 10, 1213470 (2023).

Lund, D. et al. Enhanced East Pacific Rise hydrothermal activity during the last two glacial terminations. Science 351, 478–482 (2016).

Middleton, J. L., Langmuir, C. H., Mukhopadhyay, S., McManus, J. F. & Mitrovica, J. X. Hydrothermal iron flux variability following rapid sea level changes. Geophys. Res. Lett. 43, 3848–3856 (2016).

Costa, K. M. et al. Hydrothermal deposition on the Juan de Fuca Ridge over multiple glacial–interglacial cycles. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 479, 120–132 (2017).

Martin, J. H. Glacial–interglacial CO2 change: the iron hypothesis. Paleoceanography 5, 1–13 (1990).

Lambert, F. et al. Dust fluxes and iron fertilization in Holocene and Last Glacial Maximum climates. Geophys. Res. Lett. 42, 6014–6023 (2015).

Jacobel, A. W., McManus, J. F., Anderson, R. F. & Winckler, G. Repeated storage of respired carbon in the equatorial Pacific Ocean over the last three glacial cycles. Nat. Commun. 8, 1727 (2017).

Tagliabue, A., Aumont, O. & Bopp, L. The impact of different external sources of iron on the global carbon cycle. Geophys. Res. Lett. 41, 920–926 (2014).

ETOPO 2022 15 Arc-Second Global Relief Model (NOAA National Centers for Environmental Information, accessed 15 May 2023); https://doi.org/10.25921/fd45-gt74

Orsi, A. H., Whitworth, T. & Nowlin, W. D. On the meridional extent and fronts of the Antarctic Circumpolar Current. Deep Sea Res. I 42, 641–673 (1995).

Bird, P. An updated digital model of plate boundaries. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. https://doi.org/10.1029/2001GC000252 (2003).

Peng, G., Meier, W. N., Scott, D. J. & Savoie, M. H. A long-term and reproducible passive microwave sea ice concentration data record for climate studies and monitoring. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 5, 311–318 (2013).

Reynolds, R. W. et al. Daily high-resolution-blended analyses for sea surface temperature. J. Clim. 20, 5473–5496 (2007).

Ocean Color (NASA, 2025); https://oceancolor.gsfc.nasa.gov/

Arrigo, K. R., van Dijken, G. L. & Bushinsky, S. Primary production in the Southern Ocean, 1997–2006. J. Geophys. Res. 113, C08004 (2008).

Kara, A. B., Rochfor, P. A. & Hurlburt, H. E. Naval Research Laboratory Mixed Layer Depth (NMLD) Climatologies (Naval Research Laboratory, 2002).

Gregg, W. W. & Carder, K. L. A simple spectral solar irradiance model for cloudless maritime atmospheres. Limnol. Oceanogr. 35, 1657–1675 (1990).

Dobson, F. W. & Smith, S. D. Bulk models of solar radiation at sea. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 114, 165–182 (1988).

d’Ovidio, F. et al. The biogeochemical structuring role of horizontal stirring: Lagrangian perspectives on iron delivery downstream of the Kerguelen Plateau. Biogeosciences 12, 5567–5581 (2015).

Sergi, S. et al. Interaction of the Antarctic Circumpolar Current with seamounts fuels moderate blooms but vast foraging grounds for multiple marine predators. Front. Mar. Sci. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2020.00416 (2020).

Sanial, V. et al. Study of the phytoplankton plume dynamics off the Crozet Islands (Southern Ocean): a geochemical–physical coupled approach. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 119, 2227–2237 (2014).

Sanial, V. et al. Use of Ra isotopes to deduce rapid transfer of sediment-derived inputs off Kerguelen. Biogeosciences 12, 1415–1430 (2015).

Ardyna, M. et al. Delineating environmental control of phytoplankton biomass and phenology in the Southern Ocean. Geophys. Res. Lett. 44, 5016–5024 (2017).

Earthquake Hazards Program Earthquakes (USGS, 2025); https://www.usgs.gov/natural-hazards/earthquake-hazards/earthquakes

Storchak, D. A. et al. Rebuild of the Bulletin of the International Seismological Centre (ISC)—part 2: 1980–2010. Geosci. Lett. 7, 18 (2020).

ISC Bulletin (ISC, 2025); http://www.isc.ac.uk/iscbulletin/search/

Hanks, T. C. & Kanamori, H. A moment magnitude scale. J. Geophys. Res.:Solid Earth 84, 2348–2350 (1979).

Scordilis, E. Empirical global relations converting MS and mb to moment magnitude. J. Seismol. 10, 225–236 (2006).

Aki, K. Maximum likelihood estimate of b in the formula log N = a – bM and its confidence limits. Bull. Earthq. Res. Inst. 43, 237–239 (1965).

Utsu, T. A method for determining the value of “b” in a formula log n = a – bm showing the magnitude–frequency relation for earthquakes. Geophys. Bull. Hokkaido Univ. 13, 99–103 (1965).

Schine, C., Lund Snee, J.-E., Lyford, A., Van Dijken, G. & Arrigo, K. Data used in article “Southern Ocean net primary production influenced by seismically-modulated hydrothermal iron”. Stanford Digit. Repository https://doi.org/10.25740/yc804kn7989 (2025).

Acknowledgements

We thank S. Sergi and F. D’Ovidio for their contribution to the Lagrangian plume modelling, R. Dunbar, H. Joy-Warren, C. Payne, S. Lim, M. Ardyna and M. M. Mills for their constructive comments in the early stages of investigation and D. Whitt for his support in the final phase of paper development. Any use of trade, firm or product names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the US Government. This work was supported by the National Science Foundation grant OPP 2135184, awarded to K.R.A., and by the NASA New (Early Career) Investigator Program (NIP) in Earth Science grant 20-NIP20-0113 awarded to D. Whitt.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.M.S.S. was responsible for data curation, conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, visualization and writing (original draft). J-E.L.S. was responsible for conceptualization, methodology, visualization and writing (review and editing). A.L. was responsible for formal analysis, visualization and writing (reviewing and editing). G.v.D. was responsible for data curation, methodology and writing (reviewing and editing). K.R.A. was responsible for conceptualization, supervision, funding acquisition and writing (reviewing and editing).

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Geoscience thanks Kazuhiro Misumi, Joseph Resing and Peter Strutton for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editor: James Super, in collaboration with the Nature Geoscience team.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

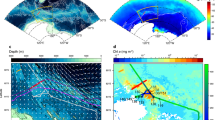

Extended Data Fig. 1 Annual integrated NPP (g C m−2 yr−1) from 1997 through 2008.

The positions of KR1 (south) and KR2 (north) are shown by the magenta lines10. The positions of the sACCf and sbACC are shown as white dotted lines from north to south, respectively, same as in Fig. 1 (ref. 48). The outline of the AAR bloom mask is shown in gray. 2008-2019 are shown in Extended Data Fig. 2.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Annual integrated NPP (g C m−2 yr−1) from 2008 through 2019.

The positions of KR1 (south) and KR2 (north) are shown by the magenta lines10. The position of the sACCf and sbACC are shown as white dotted lines from north to south, respectively, same as in Fig. 1 (ref. 48). The outline of the AAR bloom mask is shown in gray. 1997-2008 are shown in Extended Data Fig. 1.

Extended Data Fig. 3 Lagrangian plume for each growing season (Nov-Apr) showing water mass age in days for 1997 through 2008.

The positions of KR1 (south) and KR2 (north) are shown by the magenta lines10. The position of the pf, sACCf and sbACC are shown as white dotted lines from north to south, respectively, same as in Fig. 1 (ref. 48). The outline of the AAR bloom mask is shown in gray. 2008-2019 are shown in Extended Data Fig. 4.

Extended Data Fig. 4 Lagrangian plume for each growing season (Nov-Apr) showing water mass age in days for 2008 through 2019.

The positions of KR1 (south) and KR2 (north) are shown by the magenta lines10. The position of the pf, sACCf and sbACC are shown as white dotted lines from north to south, respectively, same as in Fig. 1 (ref. 48). The outline of the AAR bloom mask is shown in gray. 1997-2008 are shown in Extended Data Fig. 3.

Extended Data Fig. 5 Regression performance for models relating NPP to earthquake energy and plume area.

The R-squared and p-values shown here correspond to the relationships analyzed in Fig. 4. (a and c) are for the relationship between annual integrated Net Primary Production (NPP) and earthquake energy release and (b and d) are for the relationship between NPP and Lagrangian plume area. White dashed lines and magenta lines are as in Fig. 1 (refs. 10,48) and the gray outline shows the mask area used for spatial integrations of NPP.

Extended Data Fig. 6 Details of calculation of seasonally detrended daily NPP.

Daily spatially-integrated net primary production (NPP) from September 1997 through July 2018 (a). Seasonal component of daily NPP (b), and remainder component of NPP after seasonal cycle has been removed (c). The remainder component is used in the time-lagged correlation analysis in Fig. 4d.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figs. 1–5 and Discussion.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Schine, C.M.S., Lund Snee, JE., Lyford, A. et al. Southern Ocean net primary production influenced by seismically modulated hydrothermal iron. Nat. Geosci. 19, 106–112 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41561-025-01862-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41561-025-01862-6