Abstract

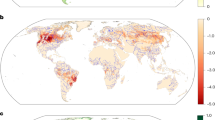

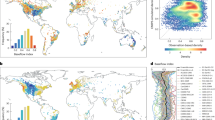

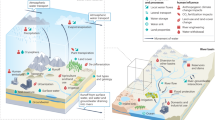

Reliable quantification of global water-cycle components, such as river flow and land evapotranspiration, remains a major challenge. Here we refine estimates of global water partitioning by combining outputs from multiple Earth system models with river flow observations from 50 large basins, applying the emergent constraint approach. Between 1980 and 2014, global river flow was (39.1 ± 5.4) × 103 km3 yr−1, with a river flow-to-precipitation ratio of 0.35 ± 0.03, both lower than previous estimates. Land evapotranspiration reached (73.4 ± 6.2) × 103 km3 yr−1. Under climate change, we project global river flow to rise by 7.8 ± 5.5 mm per year per degree of warming. This estimate, refined through the emergent constraint method, is 9.3% lower than the ensemble mean of Earth system models and reduces inter-model uncertainty by 66%. By integrating river flow observations, we provide more accurate historical estimates and strengthen future projections of global water-cycle components.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$32.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $21.58 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

Data used in the EC method for partitioning of global water-cycle components are stored at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.11096334 (ref. 78). Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

The code generating figures is available from figshare (https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.30164416) (ref. 79).

References

Oki, T. & Kanae, S. Global hydrological cycles and world water resources. Science 313, 1068–1072 (2006).

Rodell, M. & Reager, J. T. Water cycle science enabled by the GRACE and GRACE-FO satellite missions. Nat. Water 1, 47–59 (2023).

Battin, T. J. et al. River ecosystem metabolism and carbon biogeochemistry in a changing world. Nature 613, 449–459 (2023).

Humphrey, V. et al. Soil moisture–atmosphere feedback dominates land carbon uptake variability. Nature 592, 65–69 (2021).

Li, F. et al. Global water use efficiency saturation due to increased vapor pressure deficit. Science 381, 672–677 (2023).

Lapola, D. M. et al. The drivers and impacts of Amazon forest degradation. Science 379, 349–359 (2023).

Jung, M. et al. Compensatory water effects link yearly global land CO2 sink changes to temperature. Nature 541, 516–520 (2017).

Bloom, A. A., Exbrayat, J.-F., van der Velde, I. R., Feng, L. & Williams, M. The decadal state of the terrestrial carbon cycle: global retrievals of terrestrial carbon allocation, pools, and residence times. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 113, 1285–1290 (2016).

Stephens, G. L. et al. An update on Earth’s energy balance in light of the latest global observations. Nat. Geosci. 5, 691–696 (2012).

Zhang, Y. et al. Southern Hemisphere dominates recent decline in global water availability. Science 382, 579–584 (2023).

Zaitchik, B. F., Rodell, M., Biasutti, M. & Seneviratne, S. I. Wetting and drying trends under climate change. Nat. Water 1, 502–513 (2023).

Abbott, B. W. et al. Human domination of the global water cycle absent from depictions and perceptions. Nat. Geosci. 12, 533–540 (2019).

Sterling, S., Ducharne, A. & Polcher, J. The impact of global land-cover change on the terrestrial water cycle. Nat. Clim. Change 3, 385–390 (2013).

Chagas, V. B. P., Chaffe, P. L. B. & Bloeschl, G. Climate and land management accelerate the Brazilian water cycle. Nat. Commun. 13, 5136 (2022).

Shiogama, H., Watanabe, M., Kim, H. & Hirota, N. Emergent constraints on future precipitation changes. Nature 602, 612–616 (2022).

Lian, X. et al. Partitioning global land evapotranspiration using CMIP5 models constrained by observations. Nat. Clim. Change 8, 640–646 (2018).

Zhang, Y. et al. Future global streamflow declines are probably more severe than previously estimated. Nat. Water 1, 261–271 (2023).

Yang, Y. et al. Evapotranspiration on a greening Earth. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 4, 626–641 (2023).

Chen, J. M. & Liu, J. Evolution of evapotranspiration models using thermal and shortwave remote sensing data. Remote Sens. Environ. 237, 111594 (2020).

Jung, M. et al. Recent decline in the global land evapotranspiration trend due to limited moisture supply. Nature 467, 951–954 (2010).

Zhang, Y. et al. Decadal trends in evaporation from global energy and water balances. J. Hydrometeorol. 13, 379–391 (2012).

Li, H.-Y. et al. Evaluating global streamflow simulations by a physically based routing model coupled with the Community Land Model. J. Hydrometeorol. 16, 948–971 (2015).

Beven, K. A manifesto for the equifinality thesis. J. Hydrol. 320, 18–36 (2006).

Gedney, N. et al. Detection of a direct carbon dioxide effect in continental river runoff records. Nature 439, 835–838 (2006).

Piao, S. et al. Changes in climate and land use have a larger direct impact than rising CO2 on global river runoff trends. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 104, 15242–15247 (2007).

Wei, H. et al. Direct vegetation response to recent CO2 rise shows limited effect on global streamflow. Nat. Commun. 15, 9423 (2024).

Fowler, M. D., Kooperman, G. J., Randerson, J. T. & Pritchard, M. S. The effect of plant physiological responses to rising CO2 on global streamflow. Nat. Clim. Change 9, 873–879 (2019).

Ombadi, M., Risser, M. D., Rhoades, A. M. & Varadharajan, C. A warming-induced reduction in snow fraction amplifies rainfall extremes. Nature 619, 305–310 (2023).

Allen, M. R. & Ingram, W. J. Constraints on future changes in climate and the hydrologic cycle. Nature 419, 224–232 (2002).

Gnann, S. et al. Functional relationships reveal differences in the water cycle representation of global water models. Nat. Water 1, 1079–1090 (2023).

Rodell, M. et al. The observed state of the water cycle in the early twenty-first century. J. Clim. 28, 8289–8318 (2015).

Trenberth, K. E., Fasullo, J. T. & Mackaro, J. Atmospheric moisture transports from ocean to land and global energy flows in reanalyses. J. Clim. 24, 4907–4924 (2011).

Douville, H. et al. in Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis (eds Masson-Delmotte, V. et al.) 1055–1210 (IPCC, Cambridge Univ. Press, 2021).

Cox, P. M., Huntingford, C. & Williamson, M. S. Emergent constraint on equilibrium climate sensitivity from global temperature variability. Nature 553, 319–322 (2018).

Cox, P. M. et al. Sensitivity of tropical carbon to climate change constrained by carbon dioxide variability. Nature 494, 341–344 (2013).

Kwiatkowski, L. et al. Emergent constraints on projections of declining primary production in the tropical oceans. Nat. Clim. Change 7, 355–358 (2017).

Wang, X. et al. Emergent constraint on crop yield response to warmer temperature from field experiments. Nat. Sustain. 3, 908–916 (2020).

Feng, D. M. et al. Recent changes to Arctic river discharge. Nat. Commun. 12, 6917 (2021).

Spinti, R. A., Condon, L. E. & Zhang, J. The evolution of dam induced river fragmentation in the United States. Nat. Commun. 14, 3820 (2023).

Anderson, E. P. et al. Fragmentation of Andes-to-Amazon connectivity by hydropower dams. Sci. Adv. 4, eaao1642 (2018).

Feng, X. M. et al. Revegetation in China’s Loess Plateau is approaching sustainable water resource limits. Nat. Clim. Change 6, 1019–1022 (2016).

Zhang, Y. et al. Multi-decadal trends in global terrestrial evapotranspiration and its components. Sci. Rep. 6, 19124 (2016).

Haddeland, I. et al. Global water resources affected by human interventions and climate change. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 111, 3251–3256 (2014).

Elliott, J. et al. Constraints and potentials of future irrigation water availability on agricultural production under climate change. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 111, 3239–3244 (2014).

Messager, M. L. et al. Global prevalence of non-perennial rivers and streams. Nature 594, 391–397 (2021).

Huang, Q., Zhang, Y. & Wei, H. Can direct CMIP6 model simulations reproduce mean annual historical streamflow change?. CATENA 235, 107650 (2024).

Allan, R. P. et al. Advances in understanding large-scale responses of the water cycle to climate change. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 1472, 49–75 (2020).

Wagener, T., Reinecke, R. & Pianosi, F. On the evaluation of climate change impact models. WIREs Clim. Change 13, e772 (2022).

Immerzeel, W. W. et al. Importance and vulnerability of the world’s water towers. Nature 577, 364–369 (2020).

Blöschl, G. & Chaffe, P. L. B. Water scarcity is exacerbated in the south. Science 382, 512–513 (2023).

Bonan, G. B. & Doney, S. C. Climate, ecosystems, and planetary futures: the challenge to predict life in Earth system models. Science 359, 533–541 (2018).

Legge, S., Rumpff, L., Garnett, S. T. & Woinarski, J. C. Z. Loss of terrestrial biodiversity in Australia: magnitude, causation, and response. Science 381, 622–631 (2023).

Beck, H. E. et al. MSWEP V2 global 3-hourly 0.1° precipitation: methodology and quantitative assessment. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 100, 473–500 (2019).

Adler, R. F. et al. The Global Precipitation Climatology Project (GPCP) monthly analysis (new Version 2.3) and a review of 2017 global precipitation. Atmosphere 9, 138 (2018).

Lange, S. Trend-preserving bias adjustment and statistical downscaling with ISIMIP3BASD (v1.0). Geosci. Model Dev. 12, 3055–3070 (2019).

Schneider, U., Hänsel, S., Finger, P., Rustemeier, E. & Ziese, M. Global Precipitation Analysis Products of the GPCC (Global Precipitation Climatology Centre, 2022).

Dai, A. Hydroclimatic trends during 1950–2018 over global land. Clim. Dyn. 56, 4027–4049 (2021).

Peterson, T. J., Saft, M., Peel, M. C. & John, A. Watersheds may not recover from drought. Science 372, 745–749 (2021).

exactextractr: fast extraction from raster datasets using Polygons. R package v.0.10.0. GitHub https://github.com/isciences/exactextractr, https://isciences.gitlab.io/exactextractr/ (2023).

Lyne, V. & Hollick, M. Stochastic time-variable rainfall-runoff modeling. In Institute of Engineers Australia National Conference 89–93 (National Committee on Hydrology and Water Resources of the Institution of Engineers, 1979).

Boughton, W. C. A hydrograph-based model for estimating the water yield of ungauged catchments. In Hydrology and Water Resources Symposium 317–324 (Institution of Engineers, 1993).

Chapman, T. A comparison of algorithms for stream flow recession and baseflow separation. Hydrol. Processes 13, 701–714 (1999).

Low Flow Studies Report No. 1: Research Report (Institute of Hydrology, 1980).

Piggott, A. R., Moin, S. & Southam, C. A revised approach to the UKIH method for the calculation of baseflow/Une approche améliorée de la méthode de l’UKIH pour le calcul de l'écoulement de base. Hydrol. Sci. J. 50, 911–920 (2005).

Gottlieb, A. R. & Mankin, J. S. Evidence of human influence on Northern Hemisphere snow loss. Nature 625, 293–300 (2024).

Eyring, V. et al. Overview of the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project Phase 6 (CMIP6) experimental design and organization. Geosci. Model Dev. 9, 1937–1958 (2016).

Zhang, X. et al. Greening-induced increase in evapotranspiration over Eurasia offset by CO2-induced vegetational stomatal closure. Environ. Res. Lett. 16, 124008 (2021).

Zhang, Y. et al. Coupled estimation of 500 m and 8-day resolution global evapotranspiration and gross primary production in 2002–2017. Remote Sens. Environ. 222, 165–182 (2019).

Miralles, D. G. et al. Global land-surface evaporation estimated from satellite-based observations. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 15, 453–469 (2011).

Muñoz-Sabater, J. et al. ERA5-Land: a state-of-the-art global reanalysis dataset for land applications. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 13, 4349–4383 (2021).

Müller Schmied, H. et al. The global water resources and use model WaterGAP v2.2e: description and evaluation of modifications and new features. Geosci. Model Dev. Discuss. 2023, 8817–8852 (2023).

Li, C. et al. Dominant drivers for terrestrial water storage changes are different in northern and southern China. JGR Atmos. 128, e2022JD038074 (2023).

Nijsse, F. J. M. M. & Dijkstra, H. A. A mathematical approach to understanding emergent constraints. Earth Syst. Dynam. 9, 999–1012 (2018).

Gatti, L. V. et al. Amazonia as a carbon source linked to deforestation and climate change. Nature 595, 388–393 (2021).

Rodell, M. et al. Emerging trends in global freshwater availability. Nature 557, 650–659 (2018).

Weis, J. et al. One-third of Southern Ocean productivity is supported by dust deposition. Nature 629, 603–608 (2024).

Zemp, M. et al. Global glacier mass changes and their contributions to sea-level rise from 1961 to 2016. Nature 568, 382–386 (2019).

Zhang, Y. Key dataset used in the paper of “Emergent constraints reveal lower estimates of global river flow” (version v1). Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.11096334 (2024).

Zhang, Y., Wei, H., Kong, D. & Wang, L. NG_figure. figshare https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.30164416.v2 (2025).

Acknowledgements

Y.Z. acknowledges financial support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grants 42330506 and 42361144709) and the Talent Program of the Ministry of Science and Technology of China. D.K. acknowledges financial support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant 42430610). T.W. acknowledges support from the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation in the framework of the Alexander von Humboldt Professorship endowed by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF). G.B., T.W. and F.H.S.C. acknowledge support from the PIFI outstanding international team project by the Chinese Academy of Sciences. We thank the following agencies and persons for sharing or providing streamflow data used for this study: the Global Runoff Data Centre, A. Dai, Service d’observation des ressources en eaux du bassin de l’Amazone, Agência Nacional de Águas, Ministry of Water Resources of the People’s Republic of China, the Arctic Great Rivers Observatory (https://arcticgreatrivers.org/), Peterson’s dataset, Mekong River Commission (https://portal.mrcmekong.org/home) and India Water Resources Information System. We thank H. Müller Schmied for providing WaterGAP model simulation outputs. We also thank P. Döll and H. Shiogama for their comments and suggestions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.Z. designed this study, conducted most of the data analysis, prepared most of the figures and wrote the first draft. T.W., G.B. and F.H.S.C. provided critical insights into the data analysis. H.W., N.M. and C. Li collated streamflow datasets. D.K. collated CMIP6 and evapotranspiration datasets. X.L. proceeded with the WaterGAP model dataset. L.W. contributed to the global water-cycle diagram and figure optimization. All authors contributed to discussion, text revisions and result interpretations.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Geoscience thanks the anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Tamara Goldin and Aliénor Lavergne, in collaboration with the Nature Geoscience team.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figs. 1–10 and Tables 1–4.

Source data

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, Y., Blöschl, G., Wei, H. et al. Overestimation of past and future increases in global river flow by Earth system models. Nat. Geosci. (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41561-025-01897-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41561-025-01897-9