Abstract

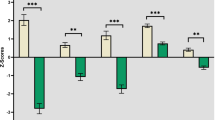

Although online samples have many advantages for psychiatric research, some potential pitfalls of this approach are not widely understood. Here we detail circumstances in which spurious correlations may arise between task behaviour and symptom scores. The problem arises because many psychiatric symptom surveys have asymmetric score distributions in the general population, meaning that careless responders on these surveys will show apparently elevated symptom levels. If these participants are similarly careless in their task performance, this may result in a spurious association between symptom scores and task behaviour. We demonstrate this pattern of results in two samples of participants recruited online (total N = 779) who performed one of two common cognitive tasks. False-positive rates for these spurious correlations increase with sample size, contrary to common assumptions. Excluding participants flagged for careless responding on surveys abolished the spurious correlations, but exclusion based on task performance alone was less effective.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$32.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 digital issues and online access to articles

$119.00 per year

only $9.92 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available on GitHub at https://github.com/nivlab/sciops.

Code availability

All code for data cleaning and analysis associated with this study is available at https://github.com/nivlab/sciops. The experiment code is available at the same link. The custom web software for serving online experiments is available at https://github.com/nivlab/nivturk.

References

Stewart, N., Chandler, J. & Paolacci, G. Crowdsourcing samples in cognitive science. Trends Cogn. Sci. 21, 736–748 (2017).

Chandler, J. & Shapiro, D. Conducting clinical research using crowdsourced convenience samples. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psycho. 12, 53–81 (2016).

Gillan, C. M. & Daw, N. D. Taking psychiatry research online. Neuron 91, 19–23 (2016).

Rutledge, R. B., Chekroud, A. M. & Huys, Q. J. Machine learning and big data in psychiatry: toward clinical applications. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 55, 152–159 (2019).

Strickland, J. C. & Stoops, W. W. The use of crowdsourcing in addiction science research: Amazon Mechanical Turk. Exp. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 27, 1–18 (2019).

Enkavi, A. Z. et al. Large-scale analysis of test–retest reliabilities of self-regulation measures. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 116, 5472–5477 (2019).

Kothe, E. & Ling, M. Retention of participants recruited to a one-year longitudinal study via Prolific. Preprint at PsyArXiv (2019).

Huang, J. L., Curran, P. G., Keeney, J., Poposki, E. M. & DeShon, R. P. Detecting and deterring insufficient effort responding to surveys. J. Bus. Psychol. 27, 99–114 (2012).

Curran, P. G. Methods for the detection of carelessly invalid responses in survey data. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 66, 4–19 (2016).

Chandler, J., Sisso, I. & Shapiro, D. Participant carelessness and fraud: consequences for clinical research and potential solutions. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 129, 49–55 (2020).

Lowe, B. et al. Validation and standardization of the generalized anxiety disorder screener (GAD-7) in the general population. Med. Care 46, 266–274 (2008).

Tomitaka, S. et al. Distributional patterns of item responses and total scores on the PHQ-9 in the general population: data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. BMC Psychiatry 18, 108 (2018).

Ophir, Y., Sisso, I., Asterhan, C. S., Tikochinski, R. & Reichart, R. The Turker blues: hidden factors behind increased depression rates among Amazon’s Mechanical Turkers. Clin. Psychol. Sci. 8, 65–83 (2020).

King, K. M., Kim, D. S. & McCabe, C. J. Random responses inflate statistical estimates in heavily skewed addictions data. Drug Alcohol Depend. 183, 102–110 (2018).

Robinson-Cimpian, J. P. Inaccurate estimation of disparities due to mischievous responders: several suggestions to assess conclusions. Educ. Res. 43, 171–185 (2014).

Huang, J. L., Liu, M. & Bowling, N. A. Insufficient effort responding: examining an insidious confound in survey data. J. Appl. Psychol. 100, 828–845 (2015).

Arias, V. B., Garrido, L., Jenaro, C., Martinez-Molina, A. & Arias, B. A little garbage in, lots of garbage out: assessing the impact of careless responding in personality survey data. Behav. Res. Methods 52, 2489–2505 (2020).

Barends, A. J. & de Vries, R. E. Noncompliant responding: comparing exclusion criteria in MTurk personality research to improve data quality. Pers. Individ. Differ. 143, 84–89 (2019).

Thomas, K. A. & Clifford, S. Validity and Mechanical Turk: an assessment of exclusion methods and interactive experiments. Comput. Hum. Behav. 77, 184–197 (2017).

Hauser, D. J. & Schwarz, N. Attentive Turkers: MTurk participants perform better on online attention checks than do subject pool participants. Behav. Res. Methods 48, 400–407 (2016).

Waltz, J. A. & Gold, J. M. Probabilistic reversal learning impairments in schizophrenia: further evidence of orbitofrontal dysfunction. Schizophr. Res. 93, 296–303 (2007).

Mukherjee, D., Filipwicz, A. L. S., Vo, K., Satterthwaite, T. D. & Kable, J. W. Reward and punishment reversal-learning in major depressive disorder. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 129, 810–823 (2020).

Huang, J. L., Bowling, N. A., Liu, M. & Li, Y. Detecting insufficient effort responding with an infrequency scale: evaluating validity and participant reactions. J. Bus. Psychol. 30, 299–311 (2015).

DeSimone, J. A. & Harms, P. Dirty data: the effects of screening respondents who provide low-quality data in survey research. J. Bus. Psychol. 33, 559–577 (2018).

Maniaci, M. R. & Rogge, R. D. Caring about carelessness: participant inattention and its effects on research. J. Res. Pers. 48, 61–83 (2014).

DeSimone, J. A., DeSimone, A. J., Harms, P. & Wood, D. The differential impacts of two forms of insufficient effort responding. Appl. Psychol. 67, 309–338 (2018).

Maydeu-Olivares, A. & Coffman, D. L. Random intercept item factor analysis. Psychol. Methods 11, 344–362 (2006).

Merikangas, K. R. et al. Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of bipolar spectrum disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 64, 543–552 (2007).

Merikangas, K. R. & Lamers, F. The ‘true’ prevalence of bipolar II disorder. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 25, 19–23 (2012).

Kessler, R. C., Petukhova, M., Sampson, N. A., Zaslavsky, A. M. & Wittchen, H.-U. Twelve-month and lifetime prevalence and lifetime morbid risk of anxiety and mood disorders in the United States. Int. J. Methods Psychiatr. Res. 21, 169–184 (2012).

Hinz, A. et al. Psychometric evaluation of the generalized anxiety disorder screener GAD-7, based on a large German general population sample. J. Affect. Disord. 210, 338–344 (2017).

Yarrington, J. S. et al. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health among 157,213 Americans. J. Affect. Disord. 286, 64–70 (2021).

Daw, N. D., Gershman, S. J., Seymour, B., Dayan, P. & Dolan, R. J. Model-based influences on humans’ choices and striatal prediction errors. Neuron 69, 1204–1215 (2011).

Elwert, F. & Winship, C. Endogenous selection bias: the problem of conditioning on a collider variable. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 40, 31–53 (2014).

Barch, D. M., Pagliaccio, D. & Luking, K. Mechanisms underlying motivational deficits in psychopathology: similarities and differences in depression and schizophrenia. Curr. Top. Behav. Neurosci. 27, 411–449 (2015).

Cohen, R., Lohr, I., Paul, R. & Boland, R. Impairments of attention and effort among patients with major affective disorders. J. Neuropsychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 13, 385–395 (2001).

Culbreth, A., Westbrook, A. & Barch, D. Negative symptoms are associated with an increased subjective cost of cognitive effort. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 125, 528–536 (2016).

Kane, M. J. et al. Individual differences in the executive control of attention, memory, and thought, and their associations with schizotypy. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 145, 1017–1048 (2016).

Robison, M. K., Gath, K. I. & Unsworth, N. The neurotic wandering mind: an individual differences investigation of neuroticism, mind-wandering, and executive control. Q. J. Exp. Psychol. 70, 649–663 (2017).

Kool, W. & Botvinick, M. Mental labour. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2, 899–908 (2018).

Kim, D. S., McCabe, C. J., Yamasaki, B. L., Louie, K. A. & King, K. M. Detecting random responders with infrequency scales using an error-balancing threshold. Behav. Res. Methods 50, 1960–1970 (2018).

Huang, H., Thompson, W. & Paulus, M. P. Computational dysfunctions in anxiety: failure to differentiate signal from noise. Biol. Psychiatry 82, 440–446 (2017).

Harlé, K. M., Guo, D., Zhang, S., Paulus, M. P. & Yu, A. J. Anhedonia and anxiety underlying depressive symptomatology have distinct effects on reward-based decision-making. PLoS ONE 12, e0186473 (2017).

Garrett, N., González-Garzón, A. M., Foulkes, L., Levita, L. & Sharot, T. Updating beliefs under perceived threat. J. Neurosci. 38, 7901–7911 (2018).

Buchanan, E. M. & Scofield, J. E. Methods to detect low quality data and its implication for psychological research. Behav. Res. Methods 50, 2586–2596 (2018).

Emons, W. H. Detection and diagnosis of person misfit from patterns of summed polytomous item scores. Appl. Psychol. Meas. 33, 599–619 (2009).

Eldar, E. & Niv, Y. Interaction between emotional state and learning underlies mood instability. Nat. Commun. 6, 6149 (2015).

Hunter, L. E., Meer, E. A., Gillan, C. M., Hsu, M. & Daw, N. D. Increased and biased deliberation in social anxiety. Nat. Hum. Behav. 6, 146–154 (2022).

Ward, M. & Meade, A. W. Applying social psychology to prevent careless responding during online surveys. Appl. Psychol. 67, 231–263 (2018).

Litman, L., Robinson, J. & Abberbock, T. Turkprime.com: a versatile crowdsourcing data acquisition platform for the behavioral sciences. Behav. Res. Methods 49, 433–442 (2017).

Litman, L. New Solutions Dramatically Improve Research Data Quality on MTurk (CloudResearch, 2020); https://www.cloudresearch.com/resources/blog/new-tools-improve-research-data-quality-mturk/

Robinson, J., Rosenzweig, C., Moss, A. J. & Litman, L. Tapped out or barely tapped? Recommendations for how to harness the vast and largely unused potential of the Mechanical Turk participant pool. PLoS ONE 14, e0226394 (2019).

de Leeuw, J. R. jsPsych: a JavaScript library for creating behavioral experiments in a web browser. Behav. Res. Methods 47, 1–12 (2015).

Youngstrom, E. A., Murray, G., Johnson, S. L. & Findling, R. L. The 7 Up 7 Down Inventory: a 14-item measure of manic and depressive tendencies carved from the General Behavior Inventory. Psychol. Assess. 25, 1377–1383 (2013).

Depue, R. A. et al. A behavioral paradigm for identifying persons at risk for bipolar depressive disorder: a conceptual framework and five validation studies. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 90, 381–437 (1981).

Spitzer, R. L., Kroenke, K., Williams, J. B. & Lowe, B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch. Intern. Med. 166, 1092–1097 (2006).

Carver, C. S. & White, T. L. Behavioral inhibition, behavioral activation, and affective responses to impending reward and punishment: the BIS/BAS scales. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 67, 319–333 (1994).

Pagliaccio, D. et al. Revising the BIS/BAS scale to study development: measurement invariance and normative effects of age and sex from childhood through adulthood. Psychol. Assess. 28, 429–442 (2016).

Cooper, A., Gomez, R. & Aucote, H. The behavioural inhibition system and behavioural approach system (BIS/BAS) scales: measurement and structural invariance across adults and adolescents. Pers. Individ. Differ. 43, 295–305 (2007).

Snaith, R. et al. A scale for the assessment of hedonic tone: the Snaith–Hamilton Pleasure Scale. Br. J. Psychiatry 167, 99–103 (1995).

Franken, I. H., Rassin, E. & Muris, P. The assessment of anhedonia in clinical and non-clinical populations: further validation of the Snaith–Hamilton Pleasure Scale (SHAPS). J. Affect. Disord. 99, 83–89 (2007).

Leventhal, A. M. et al. Measuring anhedonia in adolescents: a psychometric analysis. J. Pers. Assess. 97, 506–514 (2015).

Meyer, T. J., Miller, M. L., Metzger, R. L. & Borkovec, T. D. Development and validation of the Penn State Worry Questionnaire. Behav. Res. Ther. 28, 487–495 (1990).

Kertz, S. J., Lee, J. & Bjorgvinsson, T. Psychometric properties of abbreviated and ultra-brief versions of the Penn State Worry Questionnaire. Psychol. Assess. 26, 1146–1154 (2014).

Stan Modeling Language Users Guide and Reference Manual (Stan Development Team, 2021); https://mc-stan.org

Youngstrom, E. A., Perez Algorta, G., Youngstrom, J. K., Frazier, T. W. & Findling, R. L. Evaluating and validating GBI mania and depression short forms for self-report of mood symptoms. J. Clin. Child Adolesc. Psychol. 50, 579–595 (2020).

Marjanovic, Z., Holden, R., Struthers, W., Cribbie, R. & Greenglass, E. The inter-item standard deviation (ISD): an index that discriminates between conscientious and random responders. Pers. Individ. Differ. 84, 79–83 (2015).

Winkler, A. M., Ridgway, G. R., Webster, M. A., Smith, S. M. & Nichols, T. E. Permutation inference for the general linear model. NeuroImage 92, 381–397 (2014).

Niv, Y., Edlund, J. A., Dayan, P. & O’Doherty, J. P. Neural prediction errors reveal a risk-sensitive reinforcement-learning process in the human brain. J. Neurosci. 32, 551–562 (2012).

Brolsma, S. C. et al. Challenging the negative learning bias hypothesis of depression: reversal learning in a naturalistic psychiatric sample. Psychol. Med. 52, 303–313 (2020).

Ritschel, F. et al. Neural correlates of altered feedback learning in women recovered from anorexia nervosa. Sci. Rep. 7, 5421 (2017).

Wilcox, R. R. & Rousselet, G. A. A guide to robust statistical methods in neuroscience. Curr. Protoc. Neurosci. 82, 8–42 (2018).

Grant, M. J. & Booth, A. A typology of reviews: an analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Info. Libr. J. 26, 91–108 (2009).

Acknowledgements

We thank A. Norbury, A. Pike and O. Robinson for helpful discussion. The research reported in this article was supported in part by the National Institute of Mental Health (R01MH119511; Y.N.) and by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (UL1TR003017; Y.N.). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. S.Z. was supported by an NSF Graduate Research Fellowship. D.B. was supported by an Early Career Fellowship from the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council (no. 1165010). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.Z.: conceptualization (equal); software development (lead); data collection—online (lead); formal analysis (lead); writing—original draft (lead); writing—review and editing (supporting); visualization (lead). J.S.: software development (supporting); data collection—clinical (lead); writing—review and editing (supporting). Y.N.: writing—review and editing (equal); funding acquisition. D.B.: conceptualization (equal); software development (supporting); data collection—online (supporting); formal analysis (supporting); writing—review and editing (equal); visualization (supporting).

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Human Behaviour thanks Xiaosi Gu, Jonathan Roiser and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary materials for the original, replication and clinical studies.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Zorowitz, S., Solis, J., Niv, Y. et al. Inattentive responding can induce spurious associations between task behaviour and symptom measures. Nat Hum Behav 7, 1667–1681 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-023-01640-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-023-01640-7

This article is cited by

-

Phenotypic divergence between individuals with self-reported autistic traits and clinically ascertained autism

Nature Mental Health (2025)

-

Addressing low statistical power in computational modelling studies in psychology and neuroscience

Nature Human Behaviour (2025)

-

Model-based exploration is measurable across tasks but not linked to personality and psychiatric assessments

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

Spontaneous thought separates into clusters of negative, positive, and flexible thinking

Communications Psychology (2025)

-

Eating disorder symptoms and emotional arousal modulate food biases during reward learning in females

Nature Communications (2025)