Abstract

Human infants are born with their eyes open and an otherwise limited motor repertoire; thus, studies measuring infant looking are commonly used to investigate the developmental origins of perception and cognition. However, scholars have long expressed concerns about the reliability and interpretation of looking behaviours. We evaluated these concerns using a pre-registered (https://osf.io/jghc3), systematic meta-analysis of 76 published and unpublished studies of infants’ early physical and psychological reasoning (total n = 1,899; 3- to 12-month-old infants; database search and call for unpublished studies conducted July to August 2022). We studied two effects in the same datasets: looking towards expected versus unexpected events (violation of expectation (VOE)) and looking towards visually familiar versus visually novel events (perceptual novelty (PN)). Most studies implemented methods to minimize the risk of bias (for example, ensuring that experimenters were naive to the conditions and reporting inter-rater reliability). There was mixed evidence about publication bias for the VOE effect. Most centrally to our research aims, we found that these two effects varied systematically—with roughly equal effect sizes (VOE, standardized mean difference 0.290 and 95% confidence interval (0.208, 0.372); PN, standardized mean difference 0.239 and 95% confidence interval (0.109, 0.369))—but independently, based on different predictors. Age predicted infants’ looking responses to unexpected events, but not visually novel events. Habituation predicted infants’ looking responses to visually novel events, but not unexpected events. From these findings, we suggest that conceptual and perceptual novelty independently influence infants’ looking behaviour.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$32.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 digital issues and online access to articles

$119.00 per year

only $9.92 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

All anonymized data associated with this paper are openly available at https://osf.io/b59km/ and from Zenodo (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.12629030)79.

Code availability

All analysis scripts associated with this paper are openly available at https://osf.io/b59km/ and from Zenodo (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.12629030)79.

Change history

01 November 2024

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-024-02068-3

References

Baillargeon, R., Scott, R. M. & Bian, L. Psychological reasoning in infancy. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 67, 159–186 (2016).

Hespos, S. J. & vanMarle, K. Physics for infants: characterizing the origins of knowledge about objects, substances, and number. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Cogn. Sci. 3, 19–27 (2012).

Spelke, E. S. What Babies Know: Core Knowledge and Composition Vol. 1 (Oxford Univ. Press, 2022).

Margoni, F., Surian, L. & Baillargeon, R. The violation-of-expectation paradigm: a conceptual overview. Psychol. Rev. 131, 716–748 (2024).

Baillargeon, R., Spelke, E. S. & Wasserman, S. Object permanence in five-month-old infants. Cognition 20, 191–208 (1985).

Gergely, G., Nádasdy, Z., Csibra, G. & Bíró, S. Taking the intentional stance at 12 months of age. Cognition 56, 165–193 (1995).

Needham, A. & Baillargeon, R. Intuitions about support in 4.5-month-old infants. Cognition 47, 121–148 (1993).

Woodward, A. L. Infants selectively encode the goal object of an actor’s reach. Cognition 69, 1–34 (1998).

Blumberg, M. S. & Adolph, K. E. Protracted development of motor cortex constrains rich interpretations of infant cognition. Trends Cogn. Sci. 27, 233–245 (2023).

Cohen, L. B. & Marks, K. S. How infants process addition and subtraction events. Dev. Sci. 5, 186–201 (2002).

Paulus, M. Should infant psychology rely on the violation-of-expectation method? Not anymore. Infant Child Dev. 31, e2306 (2022).

Liu, S. & Spelke, E. S. Six-month-old infants expect agents to minimize the cost of their actions. Cognition 160, 35–42 (2017).

Byers-Heinlein, K., Bergmann, C. & Savalei, V. Six solutions for more reliable infant research. Infant Child Dev. 31, e2296 (2022).

Cohen, L. B. Uses and misuses of habituation and related preference paradigms. Infant Child Dev. 13, 349–352 (2004).

Haith, M. M. Who put the cog in infant cognition? Is rich interpretation too costly? Infant Behav. Dev. 21, 167–179 (1998).

Jackson, I. R. & Sirois, S. But that’s possible! Infants, pupils, and impossible events. Infant Behav. Dev. 67, 101710 (2022).

Bornstein, M. H., Kessen, W. & Weiskopf, S. Color vision and hue categorization in young human infants. J. Exp. Psychol. Hum. Percept. Perform. 2, 115–129 (1976).

Caron, A. J., Caron, R. F. & Carlson, V. R. Infant perception of the invariant shape of objects varying in slant. Child Dev. 50, 716–721 (1979).

Kessen, W. & Bornstein, M. H. Discriminability of brightness change for infants. J. Exp. Child Psychol. 25, 526–530 (1978).

Braddick, O. J., Atkinson, J. & Wattam-Bell, J. R. Development of the discrimination of spatial phase in infancy. Vis. Res. 26, 1223–1239 (1986).

Wattam-Bell, J. Visual motion processing in one-month-old infants: habituation experiments. Vis. Res. 36, 1679–1685 (1996).

Bergmann, C. & Cristia, A. Development of infants’ segmentation of words from native speech: a meta-analytic approach. Dev. Sci. 19, 901–917 (2016).

Enge, A., Kapoor, S., Kieslinger, A.-S. & Skeide, M. A. A meta-analysis of mental rotation in the first years of life. Dev. Sci. 26, e13381 (2023).

Rabagliati, H., Ferguson, B. & Lew-Williams, C. The profile of abstract rule learning in infancy: meta-analytic and experimental evidence. Dev. Sci. 22, e12704 (2019).

Bergmann, C., Rabagliati, H. & Tsuji, S. What’s in a looking time preference? Preprint at PsyArXiv https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/6u453 (2019).

Kosie, J. E. et al. ManyBabies 5: a large-scale investigation of the proposed shift from familiarity preference to novelty preference in infant looking time. Preprint at PsyArXiv https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/ck3vd (2023).

Koile, E. & Cristia, A. Toward cumulative cognitive science: a comparison of meta-analysis, mega-analysis, and hybrid approaches. Open Mind 5, 154–173 (2021).

Bergmann, C. et al. Promoting replicability in developmental research through meta-analyses: insights from language acquisition research. Child Dev. 89, 1996–2009 (2018).

Singh, L., Cristia, A., Karasik, L. B., Rajendra, S. J. & Oakes, L. M. Diversity and representation in infant research: barriers and bridges toward a globalized science of infant development. Infancy 28, 708–737 (2023).

Sanal-Hayes, N. E. M., Hayes, L. D., Walker, P., Mair, J. L. & Bremner, J. G. Adults’ understanding and 6-to-7-month-old infants’ perception of size and mass relationships in collision events. Appl. Sci. 12, 9846 (2022).

Duval, S. & Tweedie, R. A nonparametric ‘trim and fill’ method of accounting for publication bias in meta-analysis. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 95, 89–98 (2000).

Maier, M., VanderWeele, T. J. & Mathur, M. B. Using selection models to assess sensitivity to publication bias: a tutorial and call for more routine use. Campbell Syst. Rev. 18, e1256 (2022).

Csibra, G., Hernik, M., Mascaro, O., Tatone, D. & Lengyel, M. Statistical treatment of looking-time data. Dev. Psychol. 52, 521–536 (2016).

Richards, J. E. & Gibson, T. L. Extended visual fixation in young infants: look distributions, heart rate changes, and attention. Child Dev. 68, 1041–1056 (1997).

Šimkovic, M. & Träuble, B. Additive and multiplicative probabilistic models of infant looking times. PeerJ 9, e11771 (2021).

Van den Noortgate, W., López-López, J. A., Marín-Martínez, F. & Sánchez-Meca, J. Three-level meta-analysis of dependent effect sizes. Behav. Res. Methods 45, 576–594 (2012).

Oakes, L. M. Using habituation of looking time to assess mental processes in infancy. J. Cogn. Dev. 11, 255–268 (2010).

Aslin, R. N. What’s in a look? Dev. Sci. 10, 48–53 (2007).

Stahl, A. E. & Kibbe, M. M. Great expectations: the construct validity of the violation-of-expectation method for studying infant cognition. Infant Child Dev. 31, e2359 (2022).

Sirois, S. & Mareschal, D. Models of habituation in infancy. Trends Cogn. Sci. 6, 293–298 (2002).

Boisseau, R. P., Vogel, D. & Dussutour, A. Habituation in non-neural organisms: evidence from slime moulds. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 283, 20160446 (2016).

Turatto, M., Bonetti, F., Chiandetti, C. & Pascucci, D. Context-specific distractors rejection: contextual cues control long-term habituation of attentional capture by abrupt onsets. Vis. Cogn. 27, 291–304 (2019).

Colombo, J. & Mitchell, D. W. Infant visual habituation. Neurobiol. Learn. Mem. 92, 225–234 (2009).

Thompson, R. F. Habituation: a history. Neurobiol. Learn. Mem. 92, 127–134 (2009).

Saffran, J. R. & Kirkham, N. Z. Infant statistical learning. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 69, 181–203 (2018).

Stojnić, G., Gandhi, K., Yasuda, S., Lake, B. M. & Dillon, M. R. Commonsense psychology in human infants and machines. Cognition 235, 105406 (2023).

Shu, T. et al. AGENT: a benchmark for core psychological reasoning. In Proc. 38th International Conference on Machine Learning 9614–9625 (PMLR, 2021).

Liu, S., Ullman, T. D., Tenenbaum, J. B. & Spelke, E. S. Ten-month-old infants infer the value of goals from the costs of actions. Science 358, 1038–1041 (2017).

Kidd, C., Piantadosi, S. T. & Aslin, R. N. The goldilocks effect: human infants allocate attention to visual sequences that are neither too simple nor too complex. PLoS ONE 7, e36399 (2012).

Piloto, L. S., Weinstein, A., Battaglia, P. & Botvinick, M. Intuitive physics learning in a deep-learning model inspired by developmental psychology. Nat. Hum. Behav. 6, 1257–1267 (2022).

Smith, K. A. et al. Modeling expectation violation in intuitive physics with coarse probabilistic object representations. In Proc. 33rd Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (eds Wallach, H. et al.) 8983–8993 (Curran Associates, 2019).

Adolph, K. E., Robinson, S. R., Young, J. W. & Gill-Alvarez, F. What is the shape of developmental change? Psychol. Rev. 115, 527–543 (2008).

Siegler, R. S. & Crowley, K. The microgenetic method: a direct means for studying cognitive development. Am. Psychol. 46, 606–620 (1991).

Frank, M. C., Braginsky, M., Yurovsky, D. & Marchman, V. A. Wordbank: an open repository for developmental vocabulary data. J. Child Lang. 44, 677–694 (2017).

Bogartz, R. S., Shinskey, J. L. & Schilling, T. H. Object permanence in five-and-a-half-month-old infants? Infancy 1, 403–428 (2000).

Schilling, T. H. Infants’ looking at possible and impossible screen rotations: the role of familiarization. Infancy 1, 389–402 (2000).

Wilkinson, M. D. et al. The FAIR Guiding Principles for scientific data management and stewardship. Sci. Data 3, 160018 (2016).

Liu, S., Lydic, K., Mei, L. & Saxe, R. Violations of physical and psychological expectations in the human adult brain. Imaging Neurosci. 2, 1–25 (2024).

Pramod, R., Cohen, M. A., Tenenbaum, J. B. & Kanwisher, N. Invariant representation of physical stability in the human brain. eLife 11, e71736 (2022).

Fischer, J., Mikhael, J. G., Tenenbaum, J. B. & Kanwisher, N. Functional neuroanatomy of intuitive physical inference. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 113, E5072–E5081 (2016).

Fedorenko, E., Duncan, J. & Kanwisher, N. Broad domain generality in focal regions of frontal and parietal cortex. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 110, 16616–16621 (2013).

Page, M. J. et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Int. J. Surg. 88, 105906 (2021).

Spelke, E. S., Breinlinger, K., Macomber, J. & Jacobson, K. Origins of knowledge. Psychol. Rev. 99, 605–632 (1992).

Rohatgi, A. WebPlotDigitizer: extract data from plots, images, and maps (version 4.5). automeris.io https://automeris.io/WebPlotDigitizer/ (2022).

Venables, W. N. & Ripley, B. D. Modern Applied Statistics with S (Springer, 2003).

R Core Development Team R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2023).

Viechtbauer, W. Conducting meta-analyses in R with the metafor package. J. Stat. Softw. 36, 1–48 (2010).

Bates, D., Mächler, M., Bolker, B. & Walker, S. Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. J. Stat. Softw. 67, 1–48 (2015).

Kuznetsova, A., Brockhoff, P. B. & Christensen, R. H. B. lmerTest package: tests in linear mixed effects models. J. Stat. Softw. 82, 1–26 (2017).

Lüdecke, D., Ben-Shachar, M. S., Patil, I., Waggoner, P. & Makowski, D. performance: an R package for assessment, comparison and testing of statistical models. J. Open Source Softw. 6, 3139 (2021).

Coburn, K. M. & Vevea, J. L. weightr: estimating weight-function models for publication bias (version 2.0.2). CRAN https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=weightr (2016).

Wickham, H. ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis (Springer-Verlag, 2016).

Pedersen, T. L. patchwork: the composer of plots (version 1.1.3). CRAN https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=patchwork (2019).

Garnier, S. viridis: colorblind-friendly color maps for R (version 0.6.4). CRAN https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=viridis (2015).

Lüdecke, D. sjPlot: data visualization for statistics in social science (version 2.8.15). CRAN https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=sjPlot (2013).

Wagenmakers, E.-J. A practical solution to the pervasive problems of P values. Psychon. Bull. Rev. 14, 779–804 (2007).

Egger, M., Smith, G. D., Schneider, M. & Minder, C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. Br. Med. J. 315, 629–634 (1997).

Vevea, J. L. & Hedges, L. V. A general linear model for estimating effect size in the presence of publication bias. Psychometrika 60, 419–435 (1995).

Kunin, L., Liu, S., Piccolo, S. & Saxe, R. A systematic meta-analysis of the role of perceptual and conceptual novelty in guiding infant looking behaviour. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.12629030 (2024).

Biro, S., Csibra, G. & Gergely, G. The role of behavioral cues in understanding goal-directed actions in infancy. Prog. Brain Res. 164, 303–322 (2007).

Brandone, A. C. & Wellman, H. M. You can’t always get what you want: infants understand failed goal-directed actions. Psychol. Sci. 20, 85–91 (2009).

Choi, Y., Mou, Y. & Luo, Y. How do 3-month-old infants attribute preferences to a human agent? J. Exp. Child Psychol. 172, 96–106 (2018).

Chuey, A. et al. Moderated online data-collection for developmental research: methods and replications. Front. Psychol. 12, 734398 (2021).

Gerson, S. A. & Woodward, A. L. The joint role of trained, untrained, and observed actions at the origins of goal recognition. Infant Behav. Dev. 37, 94–104 (2014).

Gerson, S. A. & Woodward, A. L. Learning from their own actions: the unique effect of producing actions on infants’ action understanding. Child Dev. 85, 264–277 (2014).

Hernik, M. & Southgate, V. Nine-months-old infants do not need to know what the agent prefers in order to reason about its goals: on the role of preference and persistence in infants’ goal-attribution. Dev. Sci. 15, 714–722 (2012).

Hespos, S. J., Ferry, A. L. & Rips, L. J. Five-month-old infants have different expectations for solids and liquids. Psychol. Sci. 20, 603–611 (2009).

Lakusta, L. & Carey, S. Twelve-month-old infants’ encoding of goal and source paths in agentive and non-agentive motion events. Lang. Learn. Dev. 11, 152–175 (2015).

Liu, S., Brooks, N. B. & Spelke, E. S. Origins of the concepts cause, cost, and goal in prereaching infants. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 116, 17747–17752 (2019).

Liu, S. et al. Dangerous ground: one-year-old infants are sensitive to peril in other agents’ action plans. Open Mind 6, 211–231 (2022).

Liu, S., Piccolo, S. & Saxe, R. Infants’ expectations about object solidity and support, and agents’ goal-directed actions: online replications. Preprint at OSF https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/JVQDG (2024).

Liu, S. & Spelke, E. S. Infants’ understanding of inclined planes: replication of Kim & Spelke (1992) using eyetracking. Preprint at OSF https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/TBJ37 (2024).

Liu, S. & Spelke, E. S. Infants’ expectations about action efficiency and inclined planes: online replications. Preprint at OSF https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/T23X4 (2024).

Luo, Y. & Baillargeon, R. Can a self-propelled box have a goal? Psychological reasoning in 5-month-old infants. Psychol. Sci. 16, 601–608 (2005).

Luo, Y. & Baillargeon, R. When the ordinary seems unexpected: evidence for incremental physical knowledge in young infants. Cognition 95, 297–328 (2005).

Luo, Y. & Johnson, S. C. Recognizing the role of perception in action at 6 months. Dev. Sci. 12, 142–149 (2009).

Luo, Y., Kaufman, L. & Baillargeon, R. Young infants’ reasoning about physical events involving inert and self-propelled objects. Cogn. Psychol. 58, 441–486 (2009).

Luo, Y. Do 8-month-old infants consider situational constraints when interpreting others’ gaze as goal-directed action? Infancy 15, 392–419 (2010).

Luo, Y. Three-month-old infants attribute goals to a non-human agent. Dev. Sci. 14, 453–460 (2011).

Martin, A., Shelton, C. C. & Sommerville, J. A. Once a frog-lover, always a frog-lover?: infants’ goal generalization is influenced by the nature of accompanying speech. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 146, 859–871 (2017).

Olofson, E. L. & Baldwin, D. Infants recognize similar goals across dissimilar actions involving object manipulation. Cognition 118, 258–264 (2011).

Schlottmann, A., Ray, E. D. & Surian, L. Emerging perception of causality in action-and-reaction sequences from 4 to 6 months of age: is it domain-specific? J. Exp. Child Psychol. 112, 208–230 (2012).

Skerry, A. E., Carey, S. E. & Spelke, E. S. First-person action experience reveals sensitivity to action efficiency in prereaching infants. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 110, 18728–18733 (2013).

Spaepen, E. & Spelke, E. Will any doll do? 12-month-olds’ reasoning about goal objects. Cogn. Psychol. 54, 133–154 (2007).

Thoermer, C., Woodward, A., Sodian, B., Perst, H. & Kristen, S. To get the grasp: seven-month-olds encode and selectively reproduce goal-directed grasping. J. Exp. Child Psychol. 116, 499–509 (2013).

Woo, B. M., Liu, S. & Spelke, E. S. Infants rationally infer the goals of other people’s reaches in the absence of first-person experience with reaching actions. Dev. Sci. 27, e13453 (2024).

Acknowledgements

Portions of the current work were included in L.K.’s 2023 MEng thesis at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. We thank the researchers who contributed data to this project; J. Cetron at the Harvard Institute for Quantitative Social Science and M. Zettersten for statistical consultation; members of R.S.’s laboratory for helpful discussion; and the MetaLab team (https://langcog.github.io/metalab/) for their toolkit and tutorials on conducting meta-analyses on developmental data; and M. Frank and G. Raz for feedback on an earlier draft of the manuscript. We gratefully acknowledge the following funding sources: the National Institutes of Health (F32HD103363 to S.L.); Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (CW3013552 to S.H.P. and L.K.); and Massachusetts Institute of Technology Undergraduate Research Opportunities Program (to L.K.). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.K. and S.L. planned the research in consultation with S.H.P. and R.S. L.K., S.H.P. and S.L. carried out the research. L.K. analysed the data in consultation with S.L. L.K. and S.L. wrote the original draft of the paper. R.S. and S.H.P. provided critical feedback. S.L. and L.K. revised the paper in consultation with R.S.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Human Behaviour thanks Francesco Margoni, Luca Surian and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Extended Data Fig. 1 Procedure for estimating the PN and VOE effects.

(a) The data inputs, with the three critical trials are in bold (some experiments used habituation, listed here; others used familiarization; and all studies counterbalanced the order of the test events across infants). (b, c) The VOE and PN effects plotted against each other, (b) per study (N = 76 studies) or (c) per infant (N = 1482 infants). In (b), error bars around points indicate standard error of the mean (SE), and point size indicates sample size. In (b-c), a best fit line in blue was estimated using a linear model per trial type, and the grey ribbon around the line indicates the 95% confidence intervals.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Funnel plots for PN and VOE effects.

Each plot shows effect sizes (standardised mean differences) plotted against the precision (standard error) of each study (N = 76 studies total), for (a) the perceptual novelty effect, and (b) the violation-of-expectation effect. Black points indicate studies included in our primary analyses; white points were added by the trim-and-fill method to account for possible publication bias. See Methods for details.

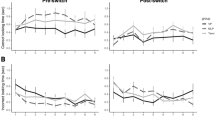

Extended Data Fig. 3 The relationship between infant age and looking time for each trial type.

Each point represents the mean looking time to one trial type for one study (N = 76 studies; ‘Last habituation / familiarization’ indicates looking on the last trial before test; ‘Expected’ indicates looking on the first expected test trial; ‘Unexpected’ indicates looking on the first unexpected test trial.) Point sizes indicate sample sizes. A best fit line estimated using a linear model per trial type is shown in blue, and error bars around points and the grey ribbon around the line indicate 95% confidence intervals. These best fit lines are unweighted (do not take into account differences in the sample sizes or variances across studies).

Extended Data Fig. 4 The relationship between exposure phase and looking time for each trial type.

Each point represents the mean looking time to one trial type for one study (N = 76 studies; ‘Last habituation / familiarization’ indicates looking on the last trial before test; ‘Expected’ indicates looking on the first expected test trial; ‘Unexpected’ indicates looking on the first unexpected test trial.). Point sizes indicate sample sizes. The centre of the box indicates the median, the bounds of the box correspond to the 25th and 75th percentiles (the interquartile range, or IQR), and the whiskers extend to the minima and maxima (up to 1.5 IQRs from the 25th and 75th percentiles). Data beyond the end of the whiskers are plotted in dark grey. Quartiles are unweighted (do not account for differences in sample size or variance across studies).

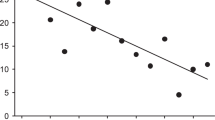

Extended Data Fig. 5 Relationship between habituation rate and the PN and VOE in individual infants from habituation studies.

(a) and (b) show scatterplots of the (a) PN and (b) VOE effects in log seconds against the number of habituation trials infants saw prior to test trials (22 studies, N = 499 infants). Each point represents one infant’s PN and VOE effects. A best fit line estimated using a linear model per trial type is shown in blue, and the grey ribbon around the line indicates 95% confidence intervals.

Extended Data Fig. 6 Relationship between habituation criteria and the PN and VOE in individual infants from familiarization studies.

(a) and (b) show boxplots of the (a) PN and (b) VOE effects in log seconds, broken down by whether infants met a standard habituation criteria by the end of the familiarization phase (21 studies, N = 603 infants). The centre of the box indicates the median, the bounds of the box correspond to the 25th and 75th percentiles (the interquartile range, or IQR), and the whiskers extend to the minima and maxima (up to 1.5 IQRs from the 25th and 75th percentiles). Data beyond the end of the whiskers are plotted in dark grey.

Extended Data Fig. 7 Full PRISMA diagram for the current research.

Thirty-three papers (76 studies) were included in the final analysis. We excluded one outlier paper (2 studies) that passed our screening process due to its extremely low variance relative to the other studies, which skewed some of the supplemental meta-analytic results. Our primary conclusions hold regardless of whether this study is included; see SI for details. Template retrieved from http://www.prisma-statement.org/PRISMAStatement/FlowDiagram.

Extended Data Fig. 8 Distribution of PN and VOE effects.

Density plot over effect sizes in standard mean differences (N = 76 studies). Meta-analytic estimate of each effect with its 95% confidence interval are shown at the bottom of the plot.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figs. 1 and 2 and Results, including Tables 1–16.

Supplementary Data 1

PRISMA checklist.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Kunin, L., Piccolo, S.H., Saxe, R. et al. Perceptual and conceptual novelty independently guide infant looking behaviour: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Nat Hum Behav 8, 2342–2356 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-024-01965-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-024-01965-x

This article is cited by

-

How physical information is used to make sense of the psychological world

Nature Reviews Psychology (2025)