Abstract

Socioeconomic status (SES) impacts health and life-course outcomes. This genome-wide association study (GWAS) of sociologically informed occupational status measures (ISEI, SIOPS, CAMSIS) using the UK Biobank (N = 273,157) identified 106 independent single-nucleotide polymorphisms of which 8 are novel to the study of SES. Genetic correlations with educational attainment (rg = 0.96–0.97) and income (rg = 0.81–0.91) point to a common genetic factor for SES. We observed a 54–57% reduction in within-family predictions compared with population-based predictions, attributed to indirect parental effects (22–27% attenuation) and assortative mating (21–27%) following our calculations. Using polygenic scores from population predictions of 5–10% (incremental R2 = 0.023–0.097 across different approaches and occupational status measures), we showed that (1) cognitive and non-cognitive traits, including scholastic and occupational motivation and aspiration, link polygenic scores to occupational status and (2) 62% of the intergenerational transmission of occupational status cannot be ascribed to genetic inheritance of common variants but other factors such as family environments. Finally, links between genetics, occupation, career trajectory and health are interrelated with parental occupational status.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Socioeconomic status (SES) stratifies society, with deep impacts on wealth1, health2, family and life course3. Various disciplines, including economics, demography, public health and sociology, have operationalized this multidimensional construct, focusing on the ‘big three’ indicators: educational attainment, income, earnings and wealth, and occupational status. Here we conduct a genome-wide association study (GWAS) on sociologically informed occupational status measures. We exploit our findings to advance understanding and quantitative modelling of status attainment processes across the life course and their complex relationship with health.

The deeply engrained intergenerational transmission of SES and inequalities across generations4,5 has motivated social and medical scientists to consider whether genetics plays a role in SES6,7,8 and, more recently, SES-related stratification and non-genetic inheritance, which biases genetic effects on a phenotype9,10. So far, the focus has primarily been on educational attainment11,12 and income13, with less attention to the heritability of occupational status. However, family studies indicate moderate heritability of occupational status comparable to other SES measures in the range of 0.30–0.40 (refs. 14,15,16,17,18). Molecular genetic research on SES proxies has focused on educational attainment6,7,19,20,21 and income22,23, neglecting occupational status. SES measures are important since they introduce gene–environment correlations which affect GWAS results24 and influence the patterns of genetic correlations of mental health traits25. This calls for a more nuanced and holistic understanding of SES that goes beyond educational attainment and income. While SES measures are intertwined, the dimensions are clearly analytically and empirically distinct26, and individuals may, for example, trade off income for other types of status, in particular occupations. Educational attainment may therefore not necessarily translate into economic success.

We extend previous work of a GWAS on broadly skill-based occupational groups using the UK Biobank, which identified 30 independent single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) associated with 9 very broad categories of the UK Standard Occupational Classification (SOC) and an SNP heritability of 0.085 (ref. 27). Since occupation in the UK Biobank is richly measured using 353 categories, we go beyond the existing GWAS by drawing from decades of sociological theory and measurement of occupational stratification. Sociological measures are preferable since purely skill-based measures suffer from inconsistent operationalization and lack theoretical and substantive thinking about the underlying mechanisms of status attainment, ignoring, for example, social prestige and other status factors1 (Box 1).

Sociologists consider occupation as the primary social and economic role held by most adults outside their immediate family or household, often even as ‘the single most important dimension in social interaction’ (p. 203)28. It is a long-term stable indicator of an individual’s social position in society alongside income, consumption, division of labour and social reproduction1. Adequately measuring occupational status is complex, with generations of sociologists dedicated to mapping this complex qualitative trait on a continuous scale29. The three conceptual approaches to measuring occupational status consider either socioeconomic differences between occupations, inter-occupational social interaction, or ascribed prestige of different jobs30.

In our analyses, we focus on three different measures of occupational status, championed by different theoretical traditions in sociology. First, the International Socioeconomic Index (ISEI)31, is a status measure constructed from scaling weights that maximize the (indirect) influence of education on income through occupation. Second, the Standard International Occupational Prestige Scale (SIOPS)28, is a prestige-based measure based on public opinion surveys where a representative population is tasked with ranking occupations by their relative social standing. Third, the Cambridge Social Interaction and Stratification Scale (CAMSIS)1, measures the distance between occupations on the basis of the frequency of social interactions between them (operationalized as husband-and-wife combinations). This measure is based on the notion that differential association is a function of social stratification, with partners and friends more likely to be selected from within the same group. Although these measures are championed by different theoretical traditions in sociology, empirically they have substantial but not perfect correlations32, alluding to an underlying latent factor of occupational status.

The current study investigates molecular genetic associations with ISEI, SIOPS and CAMSIS. Analyses were conducted on 273,157 (130,952 males and 142,205 females) individuals in the UK Biobank33, identifying 106 independent SNPs, and replicated in the UK’s National Child Development Study (NCDS; N = 4,899; 2,525 females and 2,374 males). Genomic structural equation modelling (GSEM)34 suggests a general genetic factor across all SES measures of occupational status, income and education. An overview of the study is provided in Extended Data Fig. 1.

The integration of molecular genetics into such a core topic of social science research promises a richer understanding of the role of the biological and social factors as well as the improvement of quantitative modelling and understanding of social processes of attainment status transmission. We thus utilize our GWAS discovery results for various sociogenomic investigations. While there is limited research that has identified a potential biological basis from GWAS findings for complex behavioural traits19,35, there has been some progress towards understanding potential pathways. This is particularly in psychiatric and addiction-related phenotypes and type 2 diabetes36,37,38. Accordingly, we investigated how social and psychological mechanisms play a role in the genetics of occupational status, including childhood career aspirations, non-cognitive39 and cognitive traits27. We then examined to what extent polygenic scores (PGSs) for occupational status predict the phenotype within and between families, their genetic penetrance of careers across the life course and the role common genetic variants play as a confounder of the intergenerational transmission of occupational status. Additional analyses explore the complex relationship between occupational status and health outcomes and how parental occupational status confounds the genetic prediction of general health. Our findings are conclusive that ignoring genetic data in parent–offspring SES transmission and quantitative stratification research in general leads to biased results in non-experimental studies, while the interplay between genes and the environment remains complex.

Results

Heritability, discovery and genetic links among SES measures

The main analyses were conducted on individuals from the UK Biobank on the three phenotypic measures of occupational status: CAMSIS (N = 273,157), SIOPS (N = 271,769) and ISEI (N = 271,769; Methods). Linkage disequilibrium score regression (LDSC)-based SNP heritability (\({h}_{{\rm{SNP}}}^{2}\))40 was significantly different from zero for all occupational measures, and ~50% larger for CAMSIS (\({h}_{{\rm{SNP}}}^{2}=0.145\), s.e. = 0.0066) compared with SIOPS (\({h}_{{\rm{SNP}}}^{2}=0.105\), s.e. = 0.0052) and ISEI (\({h}_{{\rm{SNP}}}^{2}=0.109\), s.e. = 0.0056, see Fig. 1). This is within the range of \({h}_{{\rm{SNP}}}^{2}\) for other status measures estimated in the UK Biobank (Methods), such as education (\({h}_{{\rm{SNP}}}^{2}=0.153\), s.e. = 0.0056) and income (\({h}_{{\rm{SNP}}}^{2}=0.092\), s.e. = 0.0041), and for CAMSIS nearly twice as high as for previously reported occupational measures27. Genome-based restricted maximum likelihood (GREML) analyses confirmed these results (Supplementary Table 1).

LD score-based SNP-heritability estimates of occupational status measures CAMSIS (N = 273,157), SIOPS (N = 271,769) and ISEI (N = 271,769) compared to income (N = 353,673) and education (N = 404,420). Each bar is a single estimate of SNP heritability and each error bar indicates the s.e. of the estimate (95% confidence intervals (CIs) are presented).

The GWASs identified 106 independent SNPs for CAMSIS, including 56 also found for ISEI and 51 for SIOPS on the basis of an R2 threshold of 0.1 and a window size of 1,000 kb (see Fig. 2 Manhattan plot), one of which (only significant for CAMSIS) was found on the X chromosome. We identified 11,206 SNPs in LD with our autosomal lead SNPs (Methods) and conducted an exhaustive phenome-wide association study (PheWAS) using the GWAS catalogue and the IEU OpenGWAS Project database. While we observe a substantial overlap with other socioeconomic status-related traits, 8 of our variants (rs12137794, rs17498867, rs10172968, rs7670291, rs26955, rs2279686, rs72744938, rs62058104) have not yet been linked to any status-related trait. For three variants (rs7670291, rs26955, rs72744938) not even suggestive associations (P < 5 × 10−6) with status traits are discernible. For two of these, we find strong links to platelet count. A full list of all implicated phenotypes is provided in Supplementary Table B8. The only non-autosomal hit (rs146852038) has previously been linked to the age of first sexual intercourse and educational attainment41.

We then replicated these hits using the National Child Development Study (NCDS), an ongoing study of a British birth cohort born in 1958 (Methods). This dataset was chosen because it is a similar UK cohort, important since previous research demonstrated genetic variation by country and birth cohort for complex behavioural phenotypes42. Despite the notable disparity in sample size, with 4,899 individuals in the NCDS compared with ~273,157 in our discovery sample, our results surpassed the expected sign concordance and achieved a higher than anticipated number of significant hits at P = 0.05 (Supplementary Information Section 7.4). This replication result underscores the robustness of our findings, even when subjected to smaller-sample constraints.

To investigate the functional implications of the genetic variants associated with occupational status, we performed gene-based and gene-set analyses using multivariate analysis of genomic annotation (MAGMA; Methods)43. We observe that genes implicated by our SNPs are expressed in the brain, including the pituitary gland. No other tissue showed significant enrichment for gene expression.

We also jointly analysed the highly correlated occupational status measures together with income and education to increase statistical power using multitrait analysis of GWAS44 (MTAG; Methods) resulting in 731, 646 and 653 variants passing the significance threshold for CAMSIS, ISEI and SIOPS, respectively.

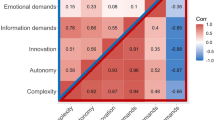

Genetic correlations (Fig. 3, lower triangle) between the three measures were close to 1 and thus stronger than the phenotypic correlations (upper triangle), ranging between 0.80 and 0.90. The genetic correlations with educational attainment and household income were almost twice as high (0.81–0.97) as their phenotypic counterparts (0.32–0.44). Considering these high genetic correlations, it is unsurprising that we found strong evidence for a common genetic factor of occupational status using genomic structural equation modelling (GSEM)34, with high loadings for all three measures (standardized path coefficients of 0.99, 0.99 and 0.99, for CAMSIS, ISEI and SIOPS, respectively; Supplementary Information Section 11). We furthermore provide evidence for a common genetic factor of SES including income and education (see Supplementary Fig. 6).

Polygenic prediction

We assessed the out-of-sample predictive performance of the PGSs using two data sources. The first sample comprised a subset of siblings from the UK Biobank, for which we conducted an additional GWAS excluding individuals from the discovery analysis. The second sample consisted of the aforementioned NCDS.

MTAG-based out-of-sample predictions, which incorporate occupational status measures with household income and educational attainment, were slightly higher in the NCDS compared with the UK Biobank, with an incremental R2 of 0.097 (s.e. = 0.0035) in NCDS across all observations (0.075, s.e. = 0.00287 in the UK Biobank) for CAMSIS, 0.065 (s.e. = 0.0032; 0.054, s.e. = 0.0025 in the UK Biobank) for ISEI and 0.067 (s.e. = 0.0031; 0.053, s.e. = 0.00248 in the UK Biobank) for SIOPS (Fig. 4). As expected, polygenic scores based on PRSice2 and SBayesR weights have smaller but comparable incremental R2 values in both UK data sets across all measures of occupational scores (Fig. 4).

Incremental R2 compared to a baseline model consisting of 10 principal components, sex and age. Bars denote 95% CIs. N = 24,579 for CAMSIS and 24,472 for ISEI and SIOPS in the UK Biobank; for NCDS average performance over different ages, N = 5,389; 5,312; 5,211; 4,902; and 4,263 for CAMSIS at ages 33, 42, 46, 50 and 55; and corresponding N = 5,449; 5,293; 5,197; 4,892; and 4,252 for ISEI/SIOPS.

The longitudinal data in the NCDS reveal changes in the PGS effects across the life course or career trajectories, respectively. First, we were able to examine PGS prediction of occupational status across the life course at ages 33, 42, 46, 50 and 55 (Supplementary Information Section 13).

By leveraging the NCDS activity calendar data, we delineated comprehensive career trajectories over 30 years, from the onset of participants’ professional lives. When stratified by PGS quintiles, parental SES and sex, these trajectories revealed a notable interplay between polygenic scores and social factors (Fig. 5). Individuals who started their careers in the lower end of occupational status scores but ranked high in the PGS consistently advanced in their careers over the years. Conversely, those who initially held higher occupational status but had lower PGSs exhibited a steady decline in their professional trajectories, as measured by occupational status scores (Supplementary Fig. 12). While our focus is on CAMSIS, similar patterns were evident for SIOPS and ISEI, underscoring the consistency of our findings (Supplementary Figs. 13 and 14). These results further highlight the importance of understanding how and why societal structures and factors correlate with genotypes and jointly predict career trajectories.

Disentangling direct, indirect and demographic effects

GWAS population estimates include a combination of direct effects (inherited genetic variation) and indirect effects or gene–environment correlations and can be further influenced by assortative mating. We conducted multiple analyses to better understand the relative importance of these dimensions in relation to our estimates (Supplementary Information Section 12)45,46.

First, we investigated the predictive performance of our scores between more than 29,500 siblings in the UK Biobank, a common design to identify direct genetic effects. Notably, traits related to socioeconomic status or other non-clinical outcomes tend to exhibit considerable within-family effect reductions45, potentially affecting their practical utility47. Our analysis supports these previous studies, showing a reduction in effects for occupational status measures of more than 50% in total, with results for other SES measures (education and income) in a similar range (see Fig. 6 for the ratio of population and within-family models and Methods).

Ratios based on within-sibship, adoption and parental-control models. N = 24,579 for CAMSIS, 24,472 for ISEI and SIOPS (within-sibship); N = 3,398 for CAMSIS and 3,414 for ISEI and SIOPS (adoption); N = 13,972 for CAMSIS and 13,973 for ISEI and SIOPS (parental control). Each estimate is the ratio of standardized beta coefficient of within-sibship, adoption or parental-control model PGS, βreduced, to the beta coefficient of population-based PGS, βPGS. The error bars represent 95% CIs calculated with the bootstrap method (1,000 repetitions).

This discrepancy between the unrelated population and within-family estimate can be attributed to indirect family effects or assortative mating. Indirect effects include the (heritable) social transmission of economic resources, and cultural and social capital, as well as social-psychological factors such as parental expectations, which represent passive gene–environment correlation. To quantify the role of indirect effects, we use two research designs. First, we adjust the best-performing PGS prediction in the NCDS for parental SES (measured as parental occupational status at age 11). Second, we conduct an adoption prediction study. In an adoption design, children are raised by non-biological parents, thereby providing a unique opportunity to examine the influence of genetic factors while minimizing the effects of passive gene–environment correlation. We re-ran our GWAS for occupational status, while excluding the set of 3,414 respondents of British-European genetic ancestry in the UK Biobank that stated that they were adopted and for which occupational information was available. Results from both designs are remarkably similar, with the parental SES showing an effect attrition of 21% for all three measures, and the adoptee prediction resulting in an effect reduction of 23%, 22% and 27% for CAMSIS, ISEI and SIOPS, respectively. Notably, our results concur with ref. 48, where the extent of attenuation for cognitive and non-cognitive skills was considerably smaller in an adoption compared with a sibling design.

The observed remaining discrepancy between the population estimate controlling for indirect effects and within-family estimates could be attributed to attrition in the within-family design due to assortative mating, which attenuates the within-family effect. Recent findings by economic historians have demonstrated strong partner matching on occupational status within the United Kingdom dating back to at least the 1750s49. By employing a method first proposed by ref. 6, we demonstrate that, even in the absence of indirect effects, within-family effects are plausibly anticipated to be attenuated by 21–27% (Supplementary Information Section 12). We find further support for attenuation by directly analysing the spousal PGS correlation, which substantially exceed what could be expected from simple phenotypical assortment (Supplementary Information Section 12). Accordingly, it closes the observed gap between both estimates. Under the assumption of additive effect reduction due to assortative mating and indirect effects, all three methods consistently estimate the proportion of direct population effects to be within the range of 73–79%. This convergence of findings underscores the importance of accounting for biases related to partner matching when examining the role of genetic factors in occupational status. It furthermore motivates the inclusion of parental SES for robustness in the application of PGS analyses downstream of the population GWAS.

Social mechanisms linking genetics and occupational status

A pertinent question to consider is which traits serve as mediators of the association between an individual’s genome and occupational status. Evidence from twin studies indicates that both cognitive and non-cognitive traits play a mediating role in the relationship between genetic and social outcomes50.

Building on previous behavioural phenotype GWASs and the literature41, we identified five traits that are potential mediators of the general genetic factor of SES: cognitive performance6, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD; as a proxy for behavioural disinhibition)51, openness to experience52, risk tolerance53 and neuroticism54. In a multivariate genetic regression model (Supplementary Information Section 11.3), overall, we can explain 70% of the genetic association with occupational status. Among these mediators, the associations are generally similar for all three measures of occupational status. Of these, the strongest effects are observed for cognitive performance. However, when we introduce ADHD and openness to experience into the models, these associations are slightly reduced. The importance of ADHD is increased by the introduction of risk tolerance. In contrast to ADHD and neuroticism, risk tolerance positively correlates with the SES factor, when controlling for the other potential mediators (see Supplementary Tables 3–5).

In the NCDS data, we tested the mediating effects of adolescent phenotypic measures of cognitive ability, externalizing behaviour, internalizing behaviour, scholastic motivation, occupational aspiration and subjective health for the occupational status PGS (Fig. 7, Methods and Supplementary Information Section 15). Depending on the career stage of the respondents indicated by NCDS waves, these variables explained 56–74% of the link between our PGSs and occupational status (Fig. 7). As expected, cognitive ability was the main mediator, explaining 33–51% of the association depending on respondents’ age. Scholastic motivation explained between 8–11%, occupational aspiration 7–11% and other non-cognitive traits up to 5%. The overall mediation by subjective health was minimal. Effect reductions are proportional when adjusting for parental SES to control for passive gene–environment correlation or indirect effects, respectively (Supplementary Information Section 11.3).

N = 3,169; 3,111; 3,075; 2,881; and 2,499 for CAMSIS at ages 33, 42, 46, 50 and 55; and corresponding N = 3,196; 3,100; 3,068; 2,878; and 2,494 for SIOPS and ISEI. Separate linear regression models with two-sided tests. Stars indicate the significance level based on P values: no star, P > 0.05; *0.01 ≤ P < 0.05; **0.001 ≤ P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001.

Intergenerational transmission

Given that parental status is strongly associated with their offspring’s status, the study of intergenerational status transmission has a long tradition, often focusing on educational attainment55,56. In the NCDS data, the phenotypic correlation between paternal occupation at age 11 and offspring occupational status at various ages for all three measures was substantial (~0.30). Including a PGS to control for genetic inheritance and identify social effects reduced the intergenerational correlation of occupational status by 11%. However, this is probably an underestimation given the power limitations of GWAS in capturing full SNP heritability. Rescaling the results to estimated SNP heritability57, up to 38% of the intergenerational correlation is due to common genetic inheritance; 62% is due to other factors, which include social inheritance and possibly the effects of rare genetic variants58 not captured by SNP-heritability estimates (see also Fig. 8 and Supplementary Information Section 16 for estimates by age).

Percentages based on the predictive validity of polygenic scores (GWAS heritability) and an extrapolation of their effect to the variance explained by common SNPs (SNP heritability). N = 3,875; 3,835; 3,747; 3,550; and 3,079 for CAMSIS at ages 33, 42, 46, 50 and 55; and corresponding N = 3,902; 3,797; 3,718; 3,522; and 3,053 for SIOPS/ISEI.

Genetic confounding between occupational status and health

Occupational status is correlated with various health outcomes and higher-SES individuals typically live longer and are in better health2. It is essential to understand to what extent this association between occupational status and health is a causal one to, for example, design effective health intervention strategies. The observed association could partly be driven by endogeneity since individuals with better health also potentially secure better jobs or have higher performance at work. Controlling for genetic associations reduces biases arising from genetic endogeneity also in regard to potential direct pleiotropic effects59. We therefore investigate to what extent the occupational status PGS confounds the observed relationship between occupational status and general health as well as mental health in the NCDS data (see Supplementary Tables 14 and 16 for regression estimates). Similar to the intergenerational transmission of status, we find significant genetic confounding in the observed relationship.

To better understand the degree to which the genotypic effect of occupational status on general and mental health might incorporate indirect effects, we analysed the health of the respondents on the basis of their occupational status PGSs with and without parental occupational status at age 11 as a control variable. In accordance with previous results, we found that taking parental occupational status into account reduced the PGS prediction of general health on average across ages and outcomes by 19.5% and of mental health by 23.7%, demonstrating the importance of considering parental SES indicators for the genetic study of offspring’s health outcomes (see Supplementary Tables 15 and 17).

Discussion

Analysing data from 273,157 individuals from the UK Biobank, we identified 106 independent SNPs associated with occupational status measures, 8 of which have not been previously reported in related SES GWASs. Our study provides PGSs that are associated with occupational status in two samples of individuals of European ancestry in the United Kingdom, with an out-of-sample prediction of 5–8% depending on the status measure and up to 9% depending on career stage. Genetic associations derived from CAMSIS were ~50% larger than for SIOPS and ISEI and twice as high as measures applied previously27. This is likely since SIOPS and ISEI are based on multicountry data from the 1970s and 1980s, and CAMSIS was constructed within the United Kingdom where our sample is located. CAMSIS conceptually focuses on social interactions, in contrast to, for example, purely skill-based measures. A potential reason for this observation may be genetic selection into interaction networks of friends60,61. A particular feature of CAMSIS is the inclusion of spousal networks. As Fisher stated, referring to past historical periods and particular contexts: “[P]revailing opinion, mutual interest and the opportunities for social intercourse, have proved themselves sufficient, in all civilized societies, to lay on the great majority of marriages the restriction that the parties shall be of approximately equal social class”62. Evidence for genetic assortative mating has been demonstrated for political views63 and educational attainment64,65, supporting strong phenotypic evidence of assortative mating by SES, race/ethnicity and religion, also showing that this has evolved with demographic change66. The heritability of CAMSIS might partly capture effects of assortative mating on the phenotype of the individual. However, high genetic correlations between CAMSIS, SIOPS and ISEI may point to the benefits of a more granular and exact measure of the same latent phenotype in CAMSIS and construction of measures within similar populations42. We also provide the R package ‘ukbjobs’ to equip researchers using the UK Biobank to employ more-standard, well-defined sociologically informed measures67.

Our study not only demonstrates the genetic interdependence of occupational status measures, but also reveals a strong genetic correlation between educational attainment, income and occupational status, identifying a common genetic factor of SES. Notably, genetic correlations among SES indicators surpass phenotypic correlations by a factor of two to three. This outcome represents an outlier from the conjecture of ref. 68, which states that phenotypic correlations can serve as proxies for genetic correlations—a notion that finds empirical support in both animals and humans69,70.

The deviation might have several reasons, including trade-offs between investments into different dimensions of SES. Higher education does not always guarantee high income or occupational status, since labour market conditions, personal networks, ethnicity and gender can influence career trajectories5. Higher occupational status does not always bring a high income or demand high education, and may vary across cultures and social contexts71. Certain genetic traits may be associated with individuals achieving higher levels in particular areas through a mechanism known as vertical pleiotropy (that is, mediated pleiotropy)23. For instance, genetic factors correlate with cognitive abilities, personality traits and mental health, which may, in turn, impact educational attainment, income and occupational status. Environmental factors such as family background, social norms, cultural expectations and chance also shape SES. Environmental differences in individual cases can lead to more heterogeneity and thus weaker phenotypic correlations, and subsequently have a completely different causal pathway in influencing health and behavioural outcomes.

We have shown that the prediction attrition within families is in part due to indirect genetic effects or genetic nurture, respectively, which also consistently contribute to the latent factor for constructed SES measures. Moreover, a mounting body of evidence suggests that strong assortative mating on this latent factor has been present for multiple generations49,72. Notably, a higher spousal correlation has been observed for the genetic predictor of educational attainment than for the actual phenotype64,73. This phenomenon may partially account for why genetic variants display a stronger predictive power for occupational status between families, as opposed to within families where the variation in these variants is more limited.

We integrated the polygenic signal for occupational status into occupational mobility and social stratification research and vice versa, with crucial implications on both sides. First, intergenerational mobility in social status is of great interest, not only for social scientists, but also policymakers, public health and epidemiology and is related to questions of equality of opportunity and societies’ degree of openness5,18,74. Next to cognitive skills, we showed that also scholastic motivation, occupational aspiration, personality traits and behavioural disinhibition (proxied by ADHD) mediate the association between genetics and occupational status. It is also vital to note that around one-third of the polygenic signal remains unexplained in each of our approaches, although it is likely that this is at least in part a result of the incomplete overlap of mediating variables between both analyses. We need further investigations to better understand the role of genetics in status inheritance and evaluate the interpretation of heritability as a pure merit measure in the context of questions addressing equality of opportunity.

Second, there are important considerations related to the intergenerational transmission of SES. It has been a common assumption in heritability studies of educational attainment that genetic influences are stable in absolute terms, while environmentally driven inequalities tend to reduce with lower intergenerational correlations8. Extrapolating results from PGSs, we show that the intergenerational correlation for occupational status is up to 38% due to genetic inheritance—this is even stronger than for educational attainment55,56. This suggests that social stratification researchers need to adjust their sole focus on intergenerational correlations to also explicitly consider gene–environment correlation in statistical modelling. We note that the applied extrapolation assumes SNP-heritability levels but could still represent an underestimation since PGSs have a lower prediction compared with SNP heritability. However, the latter is still smaller than the heritability estimated from twin models; hence, SNP heritability as measured here remains conservative compared with previous studies55. The discrepancy between SNP and twin heritability might be due to rare genetic variants, higher environmental homogeneity within families and nonlinear genetic effects42,75.

Third, we highlight questions about the causality of the relationship between health and occupational status and SES in general2. It is plausible to assume that higher status causally leads to better health, for example, due to a higher living standard, nutrition and better knowledge about and access to health care systems, among others2. At the same time (heritable) poor health might force an individual into a lower-status occupation, or genetics might have direct pleiotropic effects on education and health or related factors, leading to an overestimation of a direct, phenotypic causal effect. The question of causality, however, is paramount for designing targeted policy interventions, and genetic confounding needs to be considered. It is also relevant to quantify their potential impact and clarify claims in social mobility research regarding genetically driven, health-related confounders. We show that the association between occupational status and health is up to 25% confounded by common genetic effects and therefore substantially upward biased when genetic factors are not considered.

Fourth, combining theoretical, measurement and modelling perspectives of the social sciences and genetics is not only important for the interpretation of status in social science theory and modelling, but also for genetic research75. First, the discovery of indirect parental effects unravelled the importance of social influences correlated with genotypes in the discovery of genetic effects on education9. We show that controlling for parental occupational status strongly reduces genetic prediction of the occupational status PGS with general and mental health. While genetic prediction based on our PGSs on health is comparably small (1%) and confounding effects may not entirely generalize to other regions of the genome important for health outcomes, further investigation is required to understand whether and how parental SES measures should be integrated in population GWAS studies. Second, the continued use of the measures that have a strong theoretical, conceptual and measurement basis, such as occupational status in social stratification research, underlines the importance of precision phenotypes. Contrary to a previous GWAS that relied solely on a skill-based minimal occupational classification27, our occupational status phenotypes, which have been developed by sociologists over decades, doubled the heritability using CAMSIS, increased SNP discovery by more than threefold and also provides a consistently meaningful interpretation of the outcome variable. This also emphasizes the genetic relevance of socially theorized measures and of social factors included in them, such as potential interaction or social prestige.

Finally, our findings embrace an interdisciplinary perspective when studying social stratification, mobility and status transmission. By further studying the underlying latent factor of individual socioeconomic status indicators, we can foster a better understanding of the genetic correlates of socioeconomic status and its broader implications for society. It is imperative to comprehend the role of indirect effects and passive gene–environment correlations in this puzzle, as well as the causes and consequences of assortative mating on these relationships. The dynamic nature of the intergenerational transmission of socioeconomic status would be best served by a more comprehensive and rigorous social, historical and genetic approach.

Our study also has its limitations. The UK Biobank represents only 5.5% of the approached target population and over-represents individuals with lower mental health problems, BMI, non-smokers, with higher education and from less-economically deprived areas45,76,77,78,79. Consequently, participation bias affects the UK Biobank, limiting its generalizability and introducing the potential that observed genetic associations may be influenced by the characteristics of the subset of individuals who chose to participate in the UK Biobank80. We do show how our measures of occupational status differ from UK census data (Supplementary Information Section 6). We can expect environmental heterogeneity across different populations to challenge our findings. Accordingly, we use the NCDS sample, another UK dataset with different potential selection biases, to strengthen our analytic approach. While PGS predictions are nearly identical in our two British-European genetic ancestry populations, previous research has demonstrated that for educational attainment, only 50% of genetic effects are universal across seven Western populations42. Population genetic heterogeneity also limits the scope of this study beyond UK residents, since similar to the majority of GWAS so far, we focus on European-ancestry individuals in a Western country81,82. The integration of other ancestries, temporal, geographical and more diverse socioeconomic contexts is the future. The reduction of PGS prediction within families also emphasizes the relevance of recent initiatives for discovery designs using family data and to further study the role of assortative mating for within-family effect reduction45. It is particularly important since parental genetic factors could influence their children’s occupational status through non-genetic mechanisms, and these effects might not be adequately captured when considering only the child’s PGS. Therefore, we recognize the importance of including both parents’ PGSs as control variables to estimate genetic confounding effects, but this was not possible using the current data. This underscores the need for additional research with multigenerational genetic and social survey data. Despite these limitations, the current study offers many new insights into the interplay between genetics and occupational status scores along with socioeconomic status.

Methods

This Article has Supplementary Information with details about data and methods and additional detailed analyses. Extended Data Fig. 1 also provides an overview. We have also built the R package ‘ukbjobs’ that allows researchers to construct CAMSIS, ISEI and SIOPS occupational scores directly from the UK Biobank data (https://github.com/tobiaswolfram/ukbjobs).

Ethics approval

This research was conducted using the UK Biobank under application 32696 and NCDS under application GDAC_2021_16_TROPF, with ethics approval from the University of Oxford under application SOC_R2_001_C1A_21_60. Both the UK Biobank and NCDS applications were specific to the scope of this paper. For the UK Biobank approval, we received approval for a scope extension to ensure transparency, allowing us to expand from our focus on non-standard occupations to also include occupational status. Here we specified that our plan was “to perform GWAS analysis using employment histories from the UK Biobank to construct sociologically informed measures of occupational status”. We specified that we would construct sociologically informed measures of occupational status (CAMSIS, SIOPS and ISEI) for our GWAS and noted that the analysis would be accompanied by NCDS genetic and phenotypic data. For the NCDS application, we specified not only the information mentioned above but also the set of polygenic prediction analyses. We also preregistered our analysis plan (https://osf.io/djbr2/), which was updated for replication (https://osf.io/x6va5).

UK Biobank

For both the discovery and prediction of occupational status measures, education and income, we used data from the UK Biobank. The UK Biobank is a large-scale biomedical database and research resource containing in-depth genetic and health information from 502,655 individuals recruited between 2006 and 2010. The database is globally accessible to approved researchers. Details of the UK Biobank genotyping procedure can be found elsewhere83. After phenotype selection and genetic quality control (performed in PLINK v.1.9, v.2), we conducted our analyses on 273,157 individuals (130,952 males, 142,205 females).

NCDS

As a second, longitudinal UK prediction sample, we used the NCDS following 17,000 children born in Great Britain in 1 week in 1958. NCDS has been designed to examine the social and obstetric factors associated with stillbirth and death in early infancy. Overall, there were ten waves available (birth: 1958, age 7: 1965, age 11: 1969, age 16: 1974, age 23: 1981, age 33: 1991, age 42: 2000, age 46: 2004, age 50: 2008 and age 55: 2013).

Phenotyping

‘Socioeconomic differences’-based indices measure the ‘attributes of occupations that convert a person’s main resource (education) into a person’s main reward (income)’31. The most commonly used measure is occupational prestige, termed the International Socioeconomic Index (ISEI)31, which is constructed from scaling weights that maximize the (indirect) influence of education on income through occupation.

Other prestige-based measures are the result of public opinion surveys in which representative samples of the population are tasked with ranking occupations by their relative social standing. Emerging at a similar time as socioeconomic indices84, Treiman85 demonstrated that prestige-based measures were surprisingly constant over time and cultures, consolidating their use in social scientific research. The Standard International Occupational Prestige Scale (SIOPS or Treiman-prestige)28 remains another commonly used metric in this tradition.

Lastly, occupational status indicators derived from ‘social interaction’ focus on the heterogeneity of associations between occupants of different jobs, following the tradition of refs. 86,87. They are based on the idea that differential association is a function of social stratification since members of a group are more likely to interact within that group than with out-group members. Thus, acquaintances, friends and spouses are much more likely to be selected from within the same group than from outside. A group of Cambridge sociologists reversed this approach to measure social structure on the basis of interactions. The Cambridge Social Interaction and Stratification Scale (CAMSIS) measures the distance between occupations on the basis of the frequency of social interactions (operationalized as husband-and-wife combinations) between them1.

Information on occupational status scales was merged to the occupational classification scheme utilized in the UK Biobank (the Standard Occupational Code version 2000 (SOC2000))88. CAMSIS-based status could be directly merged using the data available in ref. 89. ISEI and SIOPS (as provided by the R package ‘strat’, R software v.4.2.0, v.4.1.2)90, however, use the less granular ISCO-88 scale, so a mapping from ISCO to SOC was employed91. If multiple job codes for a respondent were available, the most recent job was used.

‘Income’ was measured similarly as in ref. 23 using a coarse, 5-level ordinal household income variable. Educational attainment was defined as years of education and coded according to the scheme provided in ref. 6.

The prestige of ‘current’ or ‘most recent occupation’ is treated as a continuous measure. In the initial discovery analysis using the UK Biobank, respondents were asked to provide job titles for the current or the most recent job held. The job information was coded using the four-digit UK SOC2000. We built a procedure to link the UK SOC2000 to ISCO-88(COM) and then derive ISEI and SIOPS from ISCO-88(COM). All phenotypes were inverse-normal rank transformed before analysis. In the NCDS, the SOC2000 code of the respondent’s occupation (as well as their father’s when they were 11 years old), is also available, thus the same procedure was applied.

In the NCDS, we looked at ‘health’ measured at ages 23, 33, 42, 46, 50 and 55. Participants were asked to rate their general health on a scale from 1 (excellent) to 4 (poor) (age 23 and 33), 1 (excellent) to 5 (very poor) (age 42) and 1 (excellent) to 5 (poor) (age 46, 50 and 55).

For each time point, the outcome was treated as metric and standardized to have a mean of zero and a standard deviation of 1. We then regressed it on the CAMSIS, ISEI and SIOPS PGSs, respectively, while controlling for sex and 10 principal components to correct for population stratification.

Discovery

An analysis plan was preregistered and uploaded in February 2021 (https://osf.io/329pr/) and updated in February 2023 (https://osf.io/x6va5). All calculations were based on mixed-model association tests as implemented in the programme FastGWA92, with association testing based on v.3 imputed data. Following the preposted open science analysis plan in each regression, the following covariates were included: the first 10 genomic principal components, age at assessment and age2, UK Biobank (UKB) assessment centre at recruitment, sex and genotyping array (BiLEVE or Axiom) on the sample of British-European genetic ancestry. Chromosomes were analysed separately. To speed up the calculation of summary statistics, a minimum minor allele frequency (MAF) filter of 0.01 was imposed, leaving 10.2 million SNPs for the analysis. We supplemented our autosomal analyses with association analyses of SNPs on the X chromosome in a joint association analysis of both sexes.

PheWAS

All 1,000 genome SNPs in linkage disequilibrium (R2 > 0.6 for European ancestry) with the 106 independent SNPs were identified using FUMA93. For these 11,206 SNPs, 1,005,470 phenotypical associations reaching at least suggestive significance (P < 5 × 106) in the GWAS catalogue and the IEU OpenGWAS project were collected94. All variants with at least one genome-wide significant link to a trait associated with education, income or any other socioeconomic outcome were removed, leaving 8 hits (rs12137794, rs17498867, rs10172968, rs7670291, rs26955, rs2279686, rs72744938, rs62058104) that have not yet been linked to any SES-related trait. For three variants (rs7670291, rs26955, rs72744938), not even suggestive associations (P > 5 × 10−6) were found.

Univariate LDSC

Univariate LDSC regression was performed on the summary statistics from the GWAS to quantify the degree to which population stratification influenced the results and to estimate heritability (performed in Python v.3.8.4, v.3.9.15). For this, GWA test statistics were regressed onto the LD score of each SNP. LD scores were used with European genetic ancestry individuals and weights were downloaded from https://utexas.app.box.com/s/vkd36n197m8klbaio3yzoxsee6sxo11v. SNPs were included if they had a MAF of >0.01 and an imputation quality score of >0.9 and were available in the LD score file. Intercepts for all three occupational status measures were close to 1 (CAMSIS: 1.1193, s.e. = 0.013; SIOPS: 1.0845, s.e. = 0.011; ISEI: 1.0993, s.e. = 0.0125).

MAGMA

To investigate the functional implications of the genetic variants associated with occupational status, we performed gene-based and gene-set analyses using MAGMA43. We used FUMA93 to annotate, prioritize, visualize and interpret GWAS results, to run MAGMA on our summary statistics and to map SNPs to genes. We tested whether the genes prioritized by FUMA were enriched for expression in 30 general tissue types (GTEx v.8) and 53 specific tissue types (GTEx v.8) using MAGMA’s gene-set analysis. We observed a strong expression in all brain tissues compared with other tissues. No other tissue showed significant enrichment for gene expression.

MTAG

MTAG (in Python v.2.7)44 was used to meta-analyse all three occupational status measures with a secondary GWAS on household income in UKB and a secondary GWAS on educational attainment in UKB (for the validation subsample of siblings in UKB) or the third GWAS meta-analysis for education6 excluding 23andMe participants as well as the NCDS cohort (for the validation using the NCDS data). This allowed us to leverage the high genetic correlations between the occupational status measures and income/education (see above) to increase power and detect variants, and improve prediction as outlined above and in Supplementary Information Section 10.

GSEM

We used the infrastructure provided by the GenomicSEM package34 to compute LDSC-based genetic covariances and correlations between our occupational status measures and education and income. SNPs were included using similar criteria as specified for univariate LDSC. Covariance structures between the three measures of occupational status were used as input in a genomic structural equation model to analyse their loading on a joint factor of occupational status (Supplementary Information Section 11.1) We furthermore applied a multivariate genetic regression model to the genetic covariance matrix of each of our occupational status measures and cognitive performance, ADHD, openness to experience, risk tolerance and neuroticism (Supplementary Information Section 11.3).

Prediction analyses

Overall, we constructed three types of polygenic scores for each phenotype (Supplementary Information Section 10): (1) Pruning and thresholding using PRSice95, (2) SBayesR96 and (3) MTAG + SBayesR. In our prediction analyses, we residualized for sex, age (only in UKB) and 10 principal components before calculating the R2. For the within-family analysis in UK Biobank, we identified a sample of siblings and computed family-fixed-effects regressions with both polygenic scores as well as phenotypes standardized beforehand, and interpreted the change in coefficients (Supplementary Information Section 12).

Mediation analyses

NCDS respondents were asked at age 11 about the type of job they would like to do in the future. We coded these jobs to SOC2000, constructed their occupational status and ran mediation models in lavaan in R (v.4.2.0, v.4.1.2)97 to quantify the share of the association between PGS and occupational status that can be attributed to occupational aspirations. We tested a comprehensive multiple mediation model, introducing cognitive ability, internalizing behaviour, scholastic motivation and externalizing behaviour as additional mediators (Supplementary Fig. 8).

Confounding analyses

Within NCDS, information on the paternal occupation at age 12 was used to estimate the correlation between paternal and offspring occupational status at various ages for all three measures. We combined the approach of scaling the variance explained by polygenic scores, outlined in ref. 57, and integrated it into a mediation model to test which share of the intergenerational correlation for each of the three metrics was confounded by the corresponding polygenic score if we assumed that it only explained the amount of variance in our prediction analysis or the full SNP heritability (Supplementary Information Section 14).

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The GWAS summary statistics generated in this study are available on the GWAS catalogue website (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/gwas/) under accession codes GCST90446160, GCST90446162 and GCST90446163. Access to the UK Biobank is available through: http://www.ukbiobank.ac.uk. Access to The National Child Development Study (NCDS) is available through: https://cls.ucl.ac.uk/data-access-training/. PheWAS analysis was performed using the IEU OpenGWAS project data available at: https://gwas.mrcieu.ac.uk. LDSC regression analysis was performed by using LD scores and weights available at: https://utexas.app.box.com/s/vkd36n197m8klbaio3yzoxsee6sxo11v. Analysis of the representativity of the UK Biobank with the Office of National Statistics (ONS) data was performed using publicly available ONS data which can be accessed at: https://www.ons.gov.uk/employmentandlabourmarket/peopleinwork/employmentandemployeetypes/datasets/employmentbyoccupationemp04. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

The R package ‘ukbjobs’ is available at https://github.com/tobiaswolfram/ukbjobs, https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10061205. The package allows researchers to construct CAMSIS, ISEI and SIOPS occupational scores directly from the UK Biobank data. No other custom code was used; all analyses and modelling were performed using standard software as described in Methods and in Supplementary Information.

References

Lambert, P. & Griffiths, D. Social Inequalities and Occupational Stratification: Methods and Concepts in the Analysis of Social Distance (Springer, 2018).

Marmot, M. The health gap: the challenge of an unequal world: the argument. Int. J. Epidemiol. 46, 1312–1318 (2017).

Mills, M., Rindfuss, R. R., McDonald, P. & te Velde, E. Why do people postpone parenthood? Reasons and social policy incentives. Hum. Reprod. Update 17, 848–860 (2011).

Clark, G. The Son Also Rises (Princeton Univ. Press, 2014).

Breen, R. & Jonsson, J. O. Inequality of opportunity in comparative perspective: recent research on educational attainment and social mobility. Annu. Rev. Socio. 31, 223–243 (2005).

Lee, J. J. et al. Gene discovery and polygenic prediction from a genome-wide association study of educational attainment in 1.1 million individuals. Nat. Genet. 50, 1112–1121 (2018).

Belsky, D. W. et al. The genetics of success: how single-nucleotide polymorphisms associated with educational attainment relate to life-course development. Psychol. Sci. 27, 957–972 (2016).

Engzell, P. & Tropf, F. C. Heritability of education rises with intergenerational mobility. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 116, 25386–25388 (2019).

Kong, A. et al. The nature of nurture: effects of parental genotypes. Science 359, 424–428 (2018).

Wang, B. et al. Genetic nurture effects on education: a systematic review and meta-analysis based on 38,654 families across 8 cohorts. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 108, 1780–1791 (2021).

Branigan, A. R., McCallum, K. J. & Freese, J. Variation in the heritability of educational attainment: an international meta-analysis. Soc. Forces 92, 109–140 (2013).

Silventoinen, K. et al. Genetic and environmental variation in educational attainment: an individual-based analysis of 28 twin cohorts. Sci. Rep. 10, 12681 (2020).

Hyytinen, A., Ilmakunnas, P., Johansson, E. & Toivanen, O. Heritability of lifetime earnings. J. Econ. Inequal. 17, 319–335 (2019).

Behrman, J. R. Socioeconomic Success: A Study of the Effects of Genetic Endowments, Family Environment, and Schooling (North-Holland, 1980).

Neale, M. C., Walters, E. E., Eaves, L. J., Maes, H. H. & Kendler, K. S. Multivariate genetic analysis of twin-family data on fears: Mx models. Behav. Genet. 24, 119–139 (1994).

Tambs, K., Sundet, J. M., Magnus, P. & Berg, K. Genetic and environmental contributions to the covariance between occupational status, educational attainment, and IQ: a study of twins. Behav. Genet. 19, 209–222 (1989).

Marks, G. N. The contribution of genes and the environment to educational and socioeconomic attainments in Australia. Twin Res. Hum. Genet. 20, 281–289 (2017).

Erola, J., Lehti, H., Baier, T. & Karhula, A. Socioeconomic background and gene–environment interplay in social stratification across the early life course. Eur. Sociol. Rev. 38, 1–17 (2022).

Rietveld, C. A. et al. GWAS of 126,559 individuals identifies genetic variants associated with educational attainment. Science 340, 1467–1471 (2013).

Okbay, A. et al. Genome-wide association study identifies 74 loci associated with educational attainment. Nature 533, 539–542 (2016).

Belsky, D. W. et al. Genetic analysis of social-class mobility in five longitudinal studies. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 115, E7275–E7284 (2018).

Hill, W. D. et al. Molecular genetic contributions to social deprivation and household income in UK Biobank. Curr. Biol. 26, 3083–3089 (2016).

Hill, W. D. et al. Genome-wide analysis identifies molecular systems and 149 genetic loci associated with income. Nat. Commun. 10, 5741 (2019).

Abdellaoui, A., Dolan, C. V., Verweij, K. J. H. & Nivard, M. G. Gene–environment correlations across geographic regions affect genome-wide association studies. Nat. Genet. 54, 1345–1354 (2022).

Marees, A. T. et al. Genetic correlates of socio-economic status influence the pattern of shared heritability across mental health traits. Nat. Hum. Behav. 5, 1065–1073 (2021).

Geyer, S., Hemström, Ö., Peter, R. & Vågerö, D. Education, income, and occupational class cannot be used interchangeably in social epidemiology. Empirical evidence against a common practice. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 60, 804–810 (2006).

Ko, H. et al. Genome-wide association study of occupational attainment as a proxy for cognitive reserve. Brain 145, 1436–1448 (2022).

Ganzeboom, H. B. & Treiman, D. J. Internationally comparable measures of occupational status for the 1988 International Standard Classification of Occupations. Soc. Sci. Res. 25, 201–239 (1996).

Goldthorpe, J. H. Analysing social inequality: a critique of two recent contributions from economics and epidemiology. Eur. Sociol. Rev. 26, 731–744 (2010).

Connelly, R., Gayle, V. & Lambert, P. S. A review of occupation-based social classifications for social survey research. Methodol. Innov. https://doi.org/10.1177/2059799116638003 (2016).

Ganzeboom, H. B. G., De Graaf, P. M. & Treiman, D. J. A standard international socio-economic index of occupational status. Soc. Sci. Res. 21, 1–56 (1992).

Lambert, P. S. & Bihagen, E. Using occupation-based social classifications. Work Employ. Soc. 28, 481–494 (2014).

Sudlow, C. et al. UK Biobank: an open access resource for identifying the causes of a wide range of complex diseases of middle and old age. PLoS Med. 12, e1001779 (2015).

Grotzinger, A. D. et al. Genomic structural equation modelling provides insights into the multivariate genetic architecture of complex traits. Nat. Hum. Behav. 3, 513–525 (2019).

Abdellaoui, A. & Verweij, K. J. H. Dissecting polygenic signals from genome-wide association studies on human behaviour. Nat. Hum. Behav. 5, 686–694 (2021).

Antón-Galindo, E. et al. The pleiotropic contribution of genes in dopaminergic and serotonergic pathways to addiction and related behavioral traits. Front. Psychiatry 14, 1293663 (2023).

Cirillo, E. et al. From SNPs to pathways: biological interpretation of type 2 diabetes (T2DM) genome wide association study (GWAS) results. PLoS ONE 13, e0193515 (2018).

Cabana-Domínguez, J., Torrico, B., Reif, A., Fernàndez-Castillo, N. & Cormand, B. Comprehensive exploration of the genetic contribution of the dopaminergic and serotonergic pathways to psychiatric disorders. Transl. Psychiatry 12, 11 (2022).

Judge, T. A., Higgins, C. A., Thoresen, C. J. & Barrick, M. R. The big five personality traits, general mental ability, and career success across the life span. Pers. Psychol. 52, 621–652 (1999).

Finucane, H. K. et al. Partitioning heritability by functional annotation using genome-wide association summary statistics. Nat. Genet. 47, 1228–1235 (2015).

Mills, M. C. et al. Identification of 371 genetic variants for age at first sex and birth linked to externalising behaviour. Nat. Hum. Behav. 5, 1717–1730 (2021).

Tropf, F. C. et al. Hidden heritability due to heterogeneity across seven populations. Nat. Hum. Behav. 1, 757–765 (2017).

de Leeuw, C. A., Mooij, J. M., Heskes, T. & Posthuma, D. MAGMA: generalized gene-set analysis of GWAS data. PLoS Comput. Biol. 11, e1004219 (2015).

Turley, P. et al. Multi-trait analysis of genome-wide association summary statistics using MTAG. Nat. Genet. 50, 229–237 (2018).

Howe, L. J. et al. Within-sibship genome-wide association analyses decrease bias in estimates of direct genetic effects. Nat. Genet. 54, 581–592 (2022).

Mills, M. C. & Mathieson, I. The challenge of detecting recent natural selection in human populations. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 119, e2203237119 (2022).

Raben, T. G., Lello, L., Widen, E. & Hsu, S. D. From Genotype to Phenotype: polygenic prediction of complex human traits. Methods Mol. Biol. 2467, 421–446 (2022).

Demange, P. A. et al. Estimating effects of parents’ cognitive and non-cognitive skills on offspring education using polygenic scores. Nat. Commun. 13, 4801 (2022).

Clark, G. & Cummins, N. Assortative Mating and the Industrial Revolution: England, 1754–2021 CEPR Discussion Paper No. DP17074 (Centre for Economic Policy Research, 2022).

Spinath, F. M. & Bleidorn, W. The new look of behavioral genetics in social inequality: gene–environment interplay and life chances. J. Pers. 85, 5–9 (2017).

Demontis, D. et al. Discovery of the first genome-wide significant risk loci for attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Nat. Genet. 51, 63–75 (2019).

Lo, M.-T. et al. Genome-wide analyses for personality traits identify six genomic loci and show correlations with psychiatric disorders. Nat. Genet. 49, 152–156 (2017).

Karlsson Linnér, R. et al. Genome-wide association analyses of risk tolerance and risky behaviors in over 1 million individuals identify hundreds of loci and shared genetic influences. Nat. Genet. 51, 245–257 (2019).

Hill, W. D. et al. Genetic contributions to two special factors of neuroticism are associated with affluence, higher intelligence, better health, and longer life. Mol. Psychiatry 25, 3034–3052 (2020).

Conley, D. et al. Is the effect of parental education on offspring biased or moderated by genotype? Sociol. Sci. 2, 82–105 (2015).

Liu, H. Social and genetic pathways in multigenerational transmission of educational attainment. Am. Sociol. Rev. 83, 278–304 (2018).

Tucker-Drob, E. M. Measurement error correction of genome-wide polygenic scores in prediction samples. Preprint at bioRxiv https://doi.org/10.1101/165472 (2017).

Chen, C.-Y. et al. The impact of rare protein coding genetic variation on adult cognitive function. Nat. Genet. 55, 927–938 (2023).

Bulik-Sullivan, B. et al. An atlas of genetic correlations across human diseases and traits. Nat. Genet. 47, 1236–1241 (2015).

Domingue, B. W. et al. The social genome of friends and schoolmates in the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 115, 702–707 (2018).

Boardman, J. D., Domingue, B. W. & Fletcher, J. M. How social and genetic factors predict friendship networks. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 109, 17377–17381 (2012).

Fisher, R. A. The Genetical Theory of Natural Selection: A Complete Variorum Edition (Oxford Univ. Press, 1999).

Willoughby, E. A. et al. Parent contributions to the development of political attitudes in adoptive and biological families. Psychol. Sci. 32, 2023–2034 (2021).

Robinson, M. R. et al. Genetic evidence of assortative mating in humans. Nat. Hum. Behav. 1, 0016 (2017).

Torvik, F. A. et al. Modeling assortative mating and genetic similarities between partners, siblings, and in-laws. Nat. Commun. 13, 1108 (2022).

Schwartz, C. R. Trends and variation in assortative mating: causes and consequences. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 39, 451–470 (2013).

Wolfram, T. & Akimova, E. T. ukbjobs: an R package for constructing occupational scores in the UK Biobank. GitHub https://github.com/tobiaswolfram/ukbjobs (2023).

Cheverud, J. M. A comparison of genetic and phenotypic correlations. Evolution 42, 958–968 (1988).

Kruuk, L. E., Slate, J. & Wilson, A. J. New answers for old questions: the evolutionary quantitative genetics of wild animal populations. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 39, 525–548 (2008).

Sodini, S. M., Kemper, K. E., Wray, N. R. & Trzaskowski, M. Comparison of genotypic and phenotypic correlations: Cheverud’s conjecture in humans. Genetics 209, 941–948 (2018).

Kalleberg, A. L. & Sorensen, A. B. The sociology of labor markets. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 5, 351–379 (1979).

Collado, M. D., Ortuño-Ortín, I. & Stuhler, J. Estimating intergenerational and assortative processes in extended family data. Rev. Econ. Stud. 90, 1195–1227 (2023).

Okbay, A. et al. Polygenic prediction of educational attainment within and between families from genome-wide association analyses in 3 million individuals. Nat. Genet. 54, 437–449 (2022).

Narayan, A. et al. Fair Progress? Economic Mobility Across Generations Around the World (World Bank, 2018).

Mills, M. C., Barban, N. & Tropf, F. C. An Introduction to Statistical Genetic Data Analysis (MIT Press, 2020).

Fry, A. et al. Comparison of sociodemographic and health-related characteristics of UK Biobank participants with those of the general population. Am. J. Epidemiol. 186, 1026–1034 (2017).

Batty, G. D., Gale, C. R., Kivimäki, M., Deary, I. J. & Bell, S. Comparison of risk factor associations in UK Biobank against representative, general population based studies with conventional response rates: prospective cohort study and individual participant meta-analysis. Br. Med. J. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.m131 (2020).

Tyrrell, J. et al. Genetic predictors of participation in optional components of UK Biobank. Nat. Commun. 12, 886 (2021).

Pirastu, N. et al. Genetic analyses identify widespread sex-differential participation bias. Nat. Genet. 53, 663–671 (2021).

Schoeler, T. et al. Participation bias in the UK Biobank distorts genetic associations and downstream analyses. Nat. Hum. Behav. 7, 1216–1227 (2023).

Mills, M. C. & Rahal, C. The GWAS Diversity Monitor tracks diversity by disease in real time. Nat. Genet. 52, 242–243 (2020).

Mills, M. C. & Rahal, C. A scientometric review of genome-wide association studies. Commun. Biol. 2, 9 (2019).

Bycroft, C. et al. The UK Biobank resource with deep phenotyping and genomic data. Nature 562, 203–209 (2018).

Nakao, K. & Treas, J. The 1989 Socioeconomic Index of Occupations: Construction from the 1989 Occupational Prestige Scores (National Opinion Research Center, 1992).

Treiman, D. J. Occupational Prestige in Comparative Perspective (Elsevier, 2013).

Warner, W. L., Meeker, M. & Eells, K. Social Class in America; A Manual of Procedure for the Measurement of Social Status (Harper, 1949).

Laumann, E. O. & Guttman, L. The relative associational contiguity of occupations in an urban setting. Am. Sociol. Rev. 31, 169–178 (1966).

Elias, P., McKnight, A., Davies, R. & Kinshott, G. The revision of the standard occupational classification from its 1990 version to SOC2000. Labour Mark. Trends 108, 563–572 (2000).

Lambert, P. S. & Prandy, K. CAMSIS project webpages: Cambridge social interaction and stratification scales. https://www.camsis.stir.ac.uk/ (Univ. Stirling, 2012).

Hermans, M. The Strat Package: tools for social stratification research. GitHub https://github.com/mhermans/strat (2010).

Lambert, P. S. An Illustrative Guide: Using GEODE to Link Data from SOC-2000 to NS-SEC and Other Occupation-Based Social Classifications (Citeseer, 2007).

Jiang, L., Zheng, Z., Fang, H. & Yang, J. A generalized linear mixed model association tool for biobank-scale data. Nat. Genet. 53, 1616–1621 (2021).

Watanabe, K., Taskesen, E., van Bochoven, A. & Posthuma, D. Functional mapping and annotation of genetic associations with FUMA. Nat. Commun. 8, 1826 (2017).

Elsworth, B. et al. The MRC IEU OpenGWAS data infrastructure. Preprint at bioRxiv https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.08.10.244293 (2020).

Euesden, J., Lewis, C. M. & O’Reilly, P. F. PRSice: polygenic risk score software. Bioinformatics 31, 1466–1468 (2015).

Lloyd-Jones, L. R. et al. Improved polygenic prediction by Bayesian multiple regression on summary statistics. Nat. Commun. 10, 5086 (2019).

Rosseel, Y. lavaan: an R package for structural equation modeling. J. Stat. Softw. 48, 1–36 (2012).

Galton, F. in Hereditary Genius: an Inquiry into its Laws and Consequences 336–350 (Macmillan, 1869).

Martschenko, D., Trejo, S. & Domingue, B. W. Genetics and education: recent developments in the context of an ugly history and an uncertain future. AERA Open https://doi.org/10.1177/2332858418810516 (2019).

Mills, M. C. Sociogenomics: theoretical and empirical challenges in integrating molecular genetics into sociological thinking. In Handbook of Sociological Science (eds Gërxhani, K. et al.) 250–270 (Edward Elgar, 2022).

Rutherford, A. Control: The Dark History and Troubling Present of Eugenics (WW Norton, 2022).

Sorokin, P. A. Social Mobility (Harper & Brothers, 1927).

Joslyn, C. S. Sorokin on social mobility. Q. J. Econ. 42, 130–139 (1927).

Herrnstein, R. J. & Murray, C. The Bell Curve: Intelligence and Class Structure in American Life (Simon & Schuster, 2010).

Herd, P., Mills, M. C. & Dowd, J. B. Reconstructing sociogenomics research: dismantling biological race and genetic essentialism narratives. J. Health Soc. Behav. 62, 419–435 (2021).

Hingorani, A. D. et al. Performance of polygenic risk scores in screening, prediction, and risk stratification: secondary analysis of data in the Polygenic Score Catalog. BMJ Med. 2, e000554 (2023).

Meyer, M. N. et al. Wrestling with social and behavioral genomics: risks, potential benefits, and ethical responsibility. Hastings Cent. Rep. 53, S2–S49 (2023).

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; Division of Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education; Health and Medicine Division; Committee on Population; Board on Health Sciences Policy; Committee on the Use of Race, Ethnicity, and Ancestry as Population Descriptors in Genomics Research. Using Population Descriptors in Genetics and Genomics Research: A New Framework for an Evolving Field (National Academies Press, 2023).

Benonisdottir, S. & Kong, A. Studying the genetics of participation using footprints left on the ascertained genotypes. Nat. Genet. 55, 1413–1420 (2023).

Acknowledgements

This research was conducted using the UK Biobank under application 32696 and NCDS under application GDAC_2021_16_TROPF, with ethics approval from the University of Oxford under application SOC_R2_001_C1A_21_60. Both the UK Biobank and NCDS applications were specific to the scope of this paper. For the UK Biobank approval, we received approval for a scope extension to ensure transparency, allowing us to expand from our focus on non-standard occupations to also occupational status. Here we specified that our plan was: ‘to perform GWAS analysis using employment histories from the UK Biobank to construct sociologically informed measures of occupational status’. We specified that we would construct sociologically informed measures of occupational status (CAMSIS, SIOPS and ISEI) for our GWAS and noted that the analysis would be accompanied by NCDS genetic and phenotypic data. For the NCDS application, we specified not only the information mentioned above but also the set of polygenic prediction analyses. We also preregistered our analysis plan (https://osf.io/djbr2/), which was updated for replication (https://osf.io/x6va5). Funding for this project for M.C.M. and E.T.A. was from the European Research Council ERC Advanced Grant CHRONO (835079), and the Leverhulme Trust (RC-2018–003) Leverhulme Centre for Demographic Science; for M.C.M., Economic and Social Research Council, United Kingdom Science and Innovation (UKRI) Connecting Generations Grant (ES/W002116/1), MapIneq Project, European Union’s Horizon Europe research and innovation programme (No. 101061645); and for F.C.T., UKRI FINDME (EP/Y023080/1) and AnalytiXIN, which is primarily funded through the Lilly Endowment, IU Health and Eli Lilly and Company. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript. The authors thank D. M. Brazel for his important contribution and comments at the initial stage of the discovery.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.C.M. and F.C.T. supervised the study and M.C.M. led in devising and preregistering the study in 2021. T.W. and F.C.T. wrote the paper, with extensive revisions and comments from M.C.M. and E.T.A. For the Supplementary Information, M.C.M. wrote 'Frequently Asked Questions' (jointly revised with E.T.A.) and 'Background', X.D. wrote 'Representativity of the UK Biobank with the Office of National Statistics', and E.T.A. and T.W. wrote the remainder, with comments from all authors. T.W. and E.T.A. conducted statistical analyses, with input from X.D. on representativeness of occupations. M.C.M. devised and prepared Extended Data Fig. 1. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the paper.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

M.C.M. is a Trustee of the UK Biobank, is on the Scientific Advisory Board of Our Future Health and Lifelines Biobank and is on the Data Management Advisory Board of the Health and Retirement Survey. The remaining authors declare no competing interests. F.C.T. is a research fellow at AnalytiXIN, which is a consortium of health-data organizations, industry partners and university partners in Indiana primarily funded through the Lilly Endowment, IU Health and Eli Lilly and Company.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Human Behaviour thanks Hexuan Liu, Daphne Martschenko and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Extended Data Fig. 1

Study Summary Diagram.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

FAQ, Research Plan, Supplementary Background Information, Analyses, Discussion, Figs. 1–16, and Tables 1–16.

Supplementary Tables 1–8

Summary of SNPs discovered for all phenotypes; Association results for independent SNPs that reached genome-wide significance (P < 5 × 10−8) in the GWAS of International Socio-Economic Index of Occupational Status (ISEI); Association results for independent SNPs that reached genome-wide significance (P < 5 × 10−8) in the GWAS of Standard International Occupational Prestige Scale (SIOPS); Association results for independent SNPs that reached genome-wide significance (P < 5 × 10−8) in the GWAS of CAMSIS; Association results for independent autosomal SNPs that reached genome-wide significance (P < 5 × 10−8) in the multitrait GWAS (MTAG) of International Socio-Economic Index of Occupational Status (ISEI); Association results for independent autosomal SNPs that reached genome-wide significance (P < 5 × 10−8) in the MTAG of Standard International Occupational Prestige Scale (SIOPS); Association results for independent autosomal SNPs that reached genome-wide significance (P < 5 × 10−8) in the MTAG of CAMSIS; PheWAS hits for autosomal SNPs in LD (R2 > 0.6) with independent SNPs that reached genome-wide significance (P < 5 × 10−8) in the CAMSIS/ISEI/SIOPS GWASs.

Source data

Source Data Fig. 1

LD score-based SNP-heritability estimates (95% CI).

Source Data Fig. 4

Out-of-sample polygenic prediction performance within UK Biobank and NCDS. Incremental R2 compared to a baseline model consisting of 10 principal components, sex and age. Bars denote 95% confidence intervals.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Akimova, E.T., Wolfram, T., Ding, X. et al. Polygenic prediction of occupational status GWAS elucidates genetic and environmental interplay in intergenerational transmission, careers and health in UK Biobank. Nat Hum Behav 9, 391–405 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-024-02076-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-024-02076-3

This article is cited by

-

Deciphering the influence of socioeconomic status on brain structure: insights from Mendelian randomization

Molecular Psychiatry (2025)

-

Genetic associations with educational fields

Nature Genetics (2025)

-

Socio-economic status is a social construct with heritable components and genetic consequences

Nature Human Behaviour (2025)

-

Ethics of genomic research on occupational status

Nature Human Behaviour (2024)