Abstract

A defining characteristic of social complexity in Homo sapiens is the diversity of our relationships. We build connections of various types in our families, workplaces, neighbourhoods and online communities. How do we make sense of such complex systems of human relationships? The basic organization of relationships has long been studied in the social sciences, but no consensus has been reached. Here, by using online surveys, laboratory cognitive tasks and natural language processing in diverse modern cultures across the world (n = 20,427) and ancient cultures spanning 3,000 years of history, we examined universality and cultural variability in the ways that people conceptualize relationships. We discovered a universal representational space for relationship concepts, comprising five principal dimensions (formality, activeness, valence, exchange and equality) and three core categories (hostile, public and private relationships). Our work reveals the fundamental cognitive constructs and cultural principles of human relationship knowledge and advances our understanding of human sociality.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$32.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 digital issues and online access to articles

$119.00 per year

only $9.92 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

All data used in this project are accessible via GitHub (https://github.com/BNU-Wang-MSN-Lab/FAVEE-HPP) and deposited in the Open Science Framework (https://osf.io/nfkmj) and can be interactively viewed and freely downloaded at a dedicated website (https://bnu-wang-msn-lab.github.io/FAVEE-HPP). A supplementary video is also provided to elaborate the FAVEE-HPP framework (https://insula.oss-cn-chengdu.aliyuncs.com/favee/FAVEE-HPP.mp4).

Code availability

All data analysis code is available via GitHub (https://github.com/BNU-Wang-MSN-Lab/FAVEE-HPP).

References

Fiske, A. P. The four elementary forms of sociality: framework for a unified theory of social relations. Psychol. Rev. 99, 689 (1992).

Reis, H. T., Collins, W. A. & Berscheid, E. The relationship context of human behavior and development. Psychol. Bull. 126, 844 (2000).

Holt-Lunstad, J. Why social relationships are important for physical health: a systems approach to understanding and modifying risk and protection. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 69, 437–458 (2018).

Fiske, A. P. & Haslam, N. Social cognition is thinking about relationships. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 5, 143–148 (1996).

Cacioppo, J. T. & Hawkley, L. C. Perceived social isolation and cognition. Trends Cogn. Sci. 13, 447–454 (2009).

Sapolsky, R. M. The influence of social hierarchy on primate health. Science 308, 648–652 (2005).

Rai, T. S. & Fiske, A. P. Moral psychology is relationship regulation: moral motives for unity, hierarchy, equality, and proportionality. Psychol. Rev. 118, 57–75 (2011).

Argyle, M., Henderson, M. & Furnham, A. The rules of social relationships. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 24, 125–139 (1985).

Marwell, G. & Hage, J. The organization of role-relationships: a systematic description. Am. Sociol. Rev. 35, 884–900 (1970).

Wish, M., Deutsch, M. & Kaplan, S. J. Perceived dimensions of interpersonal relations. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 33, 409–420 (1976).

Montgomery, B. M. in Handbook of Personal Relationships: Theory, Research and Interventions (ed. Duck, S.) 343–359 (Wiley, 1988).

Kriegeskorte, N. & Mur, M. Inverse MDS: inferring dissimilarity structure from multiple item arrangements. Front. Psychol. 3, 245 (2012).

Burton, M. L. & Romney, A. K. A multidimensional representation of role terms. Am. Ethnol. 2, 397–407 (1975).

Freeman, J. B., Stolier, R. M., Brooks, J. A. & Stillerman, B. S. The neural representational geometry of social perception. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 24, 83–91 (2018).

Kriegeskorte, N. & Kievit, R. A. Representational geometry: integrating cognition, computation, and the brain. Trends Cogn. Sci. 17, 401–412 (2013).

Greenfield, P. M. Linking social change and developmental change: shifting pathways of human development. Dev. Psychol. 45, 401–418 (2009).

Jackson, J. C. et al. From text to thought: how analyzing language can advance psychological science. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 17, 805–826 (2022).

Grand, G., Blank, I. A., Pereira, F. & Fedorenko, E. Semantic projection recovers rich human knowledge of multiple object features from word embeddings. Nat. Hum. Behav. 6, 975–987 (2022).

Cutler, A. & Condon, D. M. Deep lexical hypothesis: identifying personality structure in natural language. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 125, 173–197 (2023).

Thornton, M. A., Wolf, S., Reilly, B. J., Slingerland, E. G. & Tamir, D. I. The 3D mind model characterizes how people understand mental states across modern and historical cultures. Affect. Sci. 3, 93–104 (2022).

Demszky, D. et al. Using large language models in psychology. Nat. Rev. Psychol. 2, 688–701 (2023).

Wang, P. & Ren, Z. The uncertainty-based retrieval framework for ancient Chinese CWS and POS. Preprint at https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2310.08496 (2023).

Baumeister, R. F. The Cultural Animal: Human Nature, Meaning, and Social Life (Oxford Univ. Press, 2005).

Cowen, A. S. et al. Sixteen facial expressions occur in similar contexts worldwide. Nature 589, 251–257 (2021).

Wood, A., Kleinbaum, A. M. & Wheatley, T. Cultural diversity broadens social networks. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 124, 109–122 (2022).

Lindquist, K. A., Jackson, J. C., Leshin, J., Satpute, A. B. & Gendron, M. The cultural evolution of emotion. Nat. Rev. Psychol. 1, 669–681 (2022).

Hamlin, J. K., Wynn, K. & Bloom, P. Social evaluation by preverbal infants. Nature 450, 557–559 (2007).

Clark, M. S. & Reis, H. T. Interpersonal processes in close relationships. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 39, 609–672 (1988).

Fiske, A. P. & Haslam, N. in Making Friends: The Influences of Culture and Development (eds Meyer, L. H. et al.) 385–392 (Paul H. Brookes, 1998).

Robins, G. & Boldero, J. Relational discrepancy theory: the implications of self-discrepancy theory for dyadic relationships and for the emergence of social structure. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 7, 56–74 (2003).

Fiske, A. P. The lexical fallacy in emotion research: mistaking vernacular words for psychological entities. Psychol. Rev. 127, 95 (2020).

Litman, L., Robinson, J. & Abberbock, T. TurkPrime.com: a versatile crowdsourcing data acquisition platform for the behavioral sciences. Behav. Res. Methods 49, 433–442 (2017).

Chen, G. et al. Online research in psychology and its future in China. J. Psychol. Sci. 46, 1262–1271 (2023).

Zhang, Z. X. Perceiving relationships with others: the Chinese dimensions. Indig. Psychol. Res. Chin. Soc. 261, 288 (1999).

Lau, K. H., Au, W. T., Lv, X. & Jiang, Y. The conceptualization of Chinese guanxi of Hong Kong University students by using multi-dimensional scaling: an empirical approach. Acta Psychol. Sin. 37, 122–125 (2005).

Wang, R. & Sang, B. A study on the characteristics and development of children’s conceptual structure of social relations. J. Psychol. Sci. 33, 1344–1351 (2010).

McInnes, L., Healy, J. & Melville, J. Umap: uniform manifold approximation and projection for dimension reduction. Preprint at https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1802.03426 (2018).

Zhao, Z. et al. UER: an open-source toolkit for pre-training models. Preprint at https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1909.05658 (2019).

Stolier, R. M., Hehman, E. & Freeman, J. B. A dynamic structure of social trait space. Trends Cogn. Sci. 22, 197–200 (2018).

Popal, H., Wang, Y. & Olson, I. R. A guide to representational similarity analysis for social neuroscience. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 14, 1243–1253 (2019).

Kriegeskorte, N., Mur, M. & Bandettini, P. Representational similarity analysis—connecting the branches of systems neuroscience. Front. Syst. Neurosci. 2, 4 (2008).

Finn, E. S. et al. Idiosynchrony: from shared responses to individual differences during naturalistic neuroimaging. NeuroImage 215, 116828 (2020).

Lin, C., Keles, U. & Adolphs, R. Four dimensions characterize attributions from faces using a representative set of English trait words. Nat. Commun. 12, 5168 (2021).

Harari, Y. N. Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind (Random House, 2014).

Acknowledgements

We thank J. Zhou, J. Yang, J. Li, Y. Wu, C. Xu, C. Mou and W. Lin for assistance in the entire project; K. Yao for help with global survey data collection; X. Zhang for help with ancient Chinese literature; 阿七尼玛次尔 (杨成龙) (NimaCier Aqi), 阿七独支玛 (DuzhiMa Aqi), 杨剑明 (J. Yang) and 和智利 (Z. He) for help with Chinese Mosuo data collection; T. Talhelm and M. Muthukrishna for sharing global cultural data; and A. P. Fiske, N. Haslem, D. M. Condon, S. Han, C. Lin, J. Zhang and X. Wang for valuable discussions and comments. This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant nos 32422033, 32171032, 32430041, 32371139, 32000776 and 31925020), the National Science and Technology Innovation 2030 Major Program (grant nos 2022ZD0211000, 2021ZD0200500 and 2021ZD0204104), Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (grant no. 2233300002), the Open Research Fund of the State Key Laboratory of Cognitive Neuroscience and Learning (grant no. CNLZD2103), the National Social Science Foundation of China (grant no. 21BZX005), National Institute of Health grants (nos R01MH091113, R01HD099165, R21HD098509, 2R56MH091113-11 and R01DC013063) and the start-up funding from the State Key Laboratory of Cognitive Neuroscience and Learning, IDG/McGovern Institute for Brain Research, Beijing Normal University (to Y.W.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

X.C., H.P., R.H. and I.R.O. designed and planned the research. X.C., H.W., M.Z. and Y.Z. performed the global data collection. X.C., H.P., H.W., R.H., M.Z. and Y.Z. analysed the data. X.C., H.P., H.W. and Y.Z. wrote the initial draft of the manuscript. R.H., M.A.T., Y.M., C.H., Y.B., J.R. and I.R.O. edited and reviewed the final manuscript. Y.W. conceived and supervised the project and was involved in all aspects of the research.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Human Behaviour thanks Alan Fiske, Christopher Cox, Daniel Hruschka and Joshua Jackson for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Extended Data Fig. 1 Existing theories in relationship science.

30 conceptual features were summarized from 15 prominent theories. Redundant features were combined across theories (see central column for final 30 features). It seems that valence and equality were the most frequently mentioned features. Note that many of these theoretical features were originally derived from dimensionality reduction or clustering techniques, but here, they were prepared to be further reduced into higher-order components. Three extra theoretical features from cross-cultural literature (that is, morality, trust, generation gap) were added for Study 2, which were not listed here. Please see more detailed information about each feature in Supplementary Table 1.

Extended Data Fig. 2 The dimensional and categorical models derived from global data (n = 17,686).

a, Four data-driven metrics consistently indicated that the optimal number for PCA was five. b, PCA loadings for five principal dimensions. c, K-means clustering solution identified three categories labelled as Hostile, Private, and Public, with the highest silhouette score of 0.295 at k = 3. These results suggested that the FAVEE-HPP model proposed in Study 1 can be well replicated by large-scale global data. In addition, for each global region, the same five dimensions and three clusters can also be identified (see Supplementary Fig. 4 and Supplementary Fig. 5).

Extended Data Fig. 3 Model comparison in performance consistency across the globe.

a, To examine how well a model can represent all theoretical relationship features, we used linear combinations of features in each model as regressors to predict each of remaining theoretical features (that were not included in that model) and calculated adjusted R2 for each region. b and c, Across global regions, FAVEE model (mean adjusted R2 = 0.489, mean BIC = 364.794) outperformed other 15 existing theories in both explained variance and data fitting, with 100,000 bootstrap resamples used to estimate the mean differences (99.9% confidence interval). Error bar (standard error) represents performance variance across 19 regions. d, Top five models in each global region (FAVEE was the best in 17 out of 19). Note: A more stringent way of model comparison was attempted where the number of predicted features was controlled between two models, and similar results were found (see Supplementary Fig. 6). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

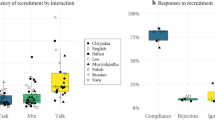

Extended Data Fig. 4 Cultural variability across relationships, dimensions, and categories.

a, Cultural variability in 159 relationship concepts. The top 15 relationships with the lowest cross-region variability were primarily familial and romantic relationships (right word cloud box), whereas the bottom 15 relationships with the highest cross-region variability were mainly affiliative and power relationships (left word cloud box). Each bar represents a single relationship, and the order was arranged according to its cross-region reliability (that is, mean LOOCV across 19 global regions). The font size of word clouds proportionally reflects the familiarity of the relationships, which was uncorrelated with cultural variability (p > 0.994). b, For three HPP categories, public relationship concepts had more culturally variable meanings than hostile and private relationship concepts (ANOVA: F(2, 36) = 41.113, P < 0.001, ηp² = 0.695; post hoc, two-tailed paired-sample t-tests (Bonferroni’s correction): ‘Hostile:Private’: t(18) = -2.015, P = 0.177; ‘Hostile:Public’: t(18) = 7.329, P < 0.001, Cohen’s d = 0.580; ‘Public:Private’: t(18) = -10.070, P < 0.001, Cohen’s d = −0.698). c, The cross-region reliability was comparable among the five principal dimensions, suggesting that no single dimension was selectively influenced by culture (ANOVA: F(4, 72) = 2.053, P = 0.096). All box plots show interquartile range (IQR) ± 1.5×IQR.

Extended Data Fig. 5 Model validation in a non-industrial society.

a, key features of the Mosuo society and its geographical location (dash line box). b, PCA showed identical FAVEE dimensions for Mosuo Chinese, Han Chinese, and world-averaged data. Through field work, we identified 75 typical relationships in Mosuo culture (see Supplementary Table 5). c, The optimal number of PCA components for Mosuo was five. d, Spearman’s correlation of loading scores across three datasets. Their derived FAVEE dimensions were well corresponded. e, K-means clustering on Mosuo relationships identified the HPP model. f, A similar dimension-category hybrid model was observed in the Mosuo society, which replicated the findings in Study 1 (see Fig. 2c).

Extended Data Fig. 6 Conceptual differences in the word ‘neighbours’ across the globe.

a, For each region, people’s understanding (conceptual beliefs) of ‘neighbours’ was estimated by interrogating its surrounding relationships in the semantic neighbourhood of representational space. Fifteen nearest relationship words were selected based on the smallest Euclidean distance with ‘neighbours’ on all evaluative features. We found that a country’s modernization level was positively correlated with the formality score of ‘neighbours’ surrounding relationships but negatively correlated with the activity intensity score (Spearman correlation, two-tailed). This suggests that as a country’s modernization level increases, ‘neighbours’ become a more public, impersonal, and superficial relationship. The shaded area represents the 95% confidence interval. b, Taking China (middle level of modernization), Israel (high level modernization) and the US (highest level of modernization) as examples. All 159 relationships were plotted in the 2D t-SNE space, with the nearby 15 relationships zoomed in for better visualization. For China, only informal relationships (in red colour) surround the Chinese word ‘neighbour’ (‘邻居’), indicating that ‘neighbours’ are considered private and personal relationships. However, for Israel and the US, an increasing number of public relationships (in blue colour) appear nearby, indicating that ‘neighbours’ are conceptualized as being more formal and impersonal. Together, these results demonstrate that although translation dictionaries provide equivalent words of relationships in different languages, their conceptual meanings are not always the same. Their variations (at least for the concept ‘neighbours’) were dependent on the country’s level of modernization (for example, ‘neighbours’ in large cities are often unknown to each other due to greater mobility led by urbanization). On the other side, these results illustrate how cultural factors such as modernization can deform the local representational geometries of relationship concepts.

Extended Data Fig. 7 Good generalizability of the FAVEE model to non-dyadic relations in the US and China.

a, PCA loadings on 33 theoretical features for group relations and triadic relations in the US (n = 380). See Supplementary Table 7 for the full list of 40 group relations and 34 triadic relations. b, In general, there were high correlations of FAVEE structures between dyadic and non-dyadic relations in the US (r = 0.73). Within non-dyadic relations, dyadic relations also showed high correlations with group relations (r = 0.76) and triadic relations (r = 0.67). c, Similar results were observed in China (n = 242), with high correlations of FAVEE structures between dyadic and non-dyadic relations (r = 0.89). d, For illustration purpose, all group relations (blue) and triadic relations (red) in the US data were plotted in the 5D space based on their scores on each FAVEE dimension.

Extended Data Fig. 8 Functionality of FAVEE dimensions and HPP categories.

The human mind involves implicit cognitive models for forming and maintaining relationships (‘relational schemas’), such as a shared understanding of the rules and norms governing interactions and the coordination of mental processes for social navigation and adaptation. The FAVEE-HPP framework posits that relationship concepts are primarily organized in a five-dimensional space with three default categories. These five dimensions might reflect different levels of motivations (for example, Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, see left arrows), for example, valence for resource competition, activeness for emotional support and belongingness, formality for social order, equality for power, and exchange for fairness. Three categories might be configured for three levels of cooperation, which echoes Roy Baumeister’s theory on how humans evolved from ‘animals’ (no cooperation, keeping hostile towards others), ‘social animals’ (small-scale cooperation based on private relationships) and to ‘cultural animals’ (large-scale cooperation based on public relationships)23. The three default HPP categories can be further classified into six canonical types of relationships, which are assumed to be associated with distinct goals, affects and behaviours. Circles and squares represent dimensions and categories, respectively. Please note that, although animals may have certain dimensions and categories, they are different from those of humans. For example, power in animals is typically defined by biological and behavioural characteristics (for example, body size, strength, vocalization), while high power in humans is often based on abstract symbols and cultural conventions (for example, reverence for elders and the divine1). Likewise, money creates a system of trust that enables exchange and cooperation between strangers in human society44.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Methods 1–3, Figs. 1–15 and Tables 1–7.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Cheng, X., Popal, H., Wang, H. et al. The conceptual structure of human relationships across modern and historical cultures. Nat Hum Behav 9, 1162–1175 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-025-02122-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-025-02122-8

This article is cited by

-

The impact of interpersonal relationship utility and intimacy on compassion fatigue among bystanders in school bullying scenarios

Current Psychology (2026)

-

The high-dimensional psychological profile of ChatGPT

Science China Technological Sciences (2025)