Abstract

Historical efforts to deinstitutionalize those experiencing mental illness in the USA have inadvertently positioned police officers as the typical first responders to emergency calls involving mental health crises and empower them to initiate involuntary psychiatric detentions. Although potentially lifesaving, such detentions are controversial and costly, and they may be medically inappropriate for some of those detained. Here we present evidence from two quasi-experimental designs on the causal effects of a ‘co-responder’ programme that pairs mental health professionals with police officers as first responders on qualified emergency calls. The results indicate that a co-responder programme reduced the frequency of involuntary psychiatric detentions by 16.5% (that is, 370 fewer detentions over 2 years; b = −0.180, 95% confidence interval −0.325 to −0.034) but had no detectable effect on programme-related calls for service, criminal offences or arrests. Complementary results based on incident-level data suggest this reduction reflects both a co-responder’s influence on the disposition of an individual incident and a reduction in future mental health emergencies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Emergency calls for service involving individuals experiencing a mental health crisis often result in sending police officers as first responders—even when the details of the call do not suggest a crime has occurred. Widespread public criticism has called this routine practice into question, particularly in response to highly visible instances in which police use of force results in the death of someone in mental health distress1,2,3,4,5,6. However, another substantive concern is that police officers are often empowered to order involuntary psychiatric detentions, but have little to no mental health training relevant to make these determinations appropriately7. In general, whether the procedures for making such involuntary detentions are valid and consistent is—both medically and ethically—a prominent and increasingly relevant source of controversy8. Following national efforts to deinstitutionalize those with serious mental illness in the 1950s and 1960s, the US Congress, Supreme Court and associations of psychiatrists affirmed that involuntary emergency detentions for mental health reasons should be limited (usually to 72 h or less) and enacted only for those whose mental health distress renders them a danger to themselves or others9,10. Involuntary psychiatric detention laws have subsequently been enacted in all 50 states due to their potential to offer last-resort lifesaving care to those experiencing suicidal, homicidal or other acute mental health crises. However, for those posing no danger to themselves or others, even temporary involuntary detention in a psychiatric facility may be medically harmful, inhumane and financially costly relative to first responses that instead facilitate appropriate and ongoing outpatient care8,11,12,13,14.

Recent data indicate that the rates of involuntary psychiatric detentions have increased and exhibit an extraordinary 33-fold variation across US states15. Police involvement is strongly associated with an increased likelihood that an individual in crisis is involuntarily detained rather than receiving other forms of health care16,17. These trends may emerge from a growing understanding among police officers that individuals experiencing mental illness do not belong in jail, but they believe that some form of intervention is necessary for public safety18. However, although there may be benefits of involuntary detentions for some, many have later characterized their police engagement and subsequent detention as criminalizing and unbeneficial rather than therapeutic19,20. Similarly, critics argue that such involuntary detentions and commitments can serve as a ‘reinstitutionalizing’ of those experiencing mental illness through a medicalized form of arrest and incarceration for individuals in health crises21,22—and it remains unclear whether the benefits of involuntary psychiatric detentions outweigh the risks for some individuals and communities11,23,24.

In response to public concerns about the prevalence of involuntary psychiatric detentions—and conventional law enforcement responses to mental health crises more broadly—many US communities have piloted programmes seeking to augment their emergency first-response protocols. One common approach is a ‘co-responder’ programme, which sends mental health clinicians out as first responders along with police officers—either simultaneously or after the scene of the incident has been deemed safe for the clinician25. Some limited evidence suggests the promise of mental health co-responder programmes. One study out of Colorado suggests the presence of co-responder programmes corresponds to reductions in the number of involuntary psychiatric detentions in affected communities26. Yet, that study’s authors acknowledge that “there is no way to know what would have actually happened had the co-responder not been there using the current method” (p. 4). Another cross-sectional study based on 533 incidents in a Florida county finds that, when police officers request a co-responder in response to a youth in crisis, the likelihood that the youth is examined for an involuntary commitment decreases27. However, we know of no existing studies providing credibly causal evidence on the incident- and community-level effectiveness of co-responder programmes for any policy-relevant outcomes.

This study presents quasi-experimental evidence on the impacts of a co-responder programme (that is, the Community Wellness and Crisis Response Team, CWCRT) implemented in several communities in San Mateo County, CA (see Supplementary Fig. 1 for locations of these communities and ‘CWCRT programme description’ in Supplementary Information for details on this programme and its context). Our results are based on two complementary quasi-experimental research designs and four specific outcome measures that we preregistered with the Open Science Framework (https://osf.io/dbs35) before analysis (that is, involuntary psychiatric detentions, programme-relevant calls for service, criminal offences and arrests resulting from those calls). The first design examines neighbourhood-level panel data observed monthly over a period when roughly half the neighbourhoods began participating in a co-responder programme. This ‘difference-in-differences’ (DiD) analysis effectively compares the outcome changes in neighbourhoods that introduce co-responders with the contemporaneous changes in comparison neighbourhoods that do not. Our second design focuses only on individual, programme-eligible incidents from the neighbourhoods with active co-responder operations. This incident-level approach conditions on fixed effects unique to each neighbourhood, each month–year, each day of the week and each hour of the day and effectively compares outcomes among programme-eligible incidents that receive a co-responder and those that do not (for example, due to staff unavailability). Additional details on these methods can be found in Methods.

Results

We begin with considering the CWCRT programme’s total effects, which include combined programmatic effects on the disposition of individual incidents at the moment of emergency response (for example, the likelihood of an involuntary psychiatric detention) and those due to broad changes in the frequency of such programme-relevant incidents in treated neighbourhoods over time (for example, possible reductions due to lowering the incidence of untreated and recurring mental health incidents). Our preregistered research design relies on neighbourhood-by-month panel data from each of 48 mutually exclusive and exhaustive neighbourhoods from 9 cities in San Mateo County, CA, observed monthly from January 2019 through June 2023 (see Supplementary Table 1 for descriptive statistics of the sample). The key identifying assumption of the DiD design based on these data is that the untreated potential outcomes between the treatment and comparison neighbourhoods have parallel trends over time. We examine this assumption by examining event-study estimates that compare outcome trends across treatment and comparison neighbourhoods in the months just before CWCRT operations (Supplementary Table 5). Given the count nature of the outcomes, we estimate the programme impacts using conditional maximum likelihood Poisson and negative binomial specifications with bootstrapped standard errors, clustered at the neighbourhood level. With the natural logarithm as the link function, the resulting estimates represent the approximate per cent change in the outcome to the CWCRT programme.

Figure 1 displays the estimated treatment effects of the CWCRT programme on each confirmatory outcome (see also Supplementary Table 3). The results indicate that, when the co-responder programme became available, there was a statistically significant reduction in the number of involuntary psychiatric detentions made in those neighbourhoods (coefficient point estimate (b) = −0.180, 95% confidence interval (CI) −0.325 to −0.034, P = 0.0154). This point estimate implies that the co-responder programme reduced involuntary psychiatric detentions by 16.5% (that is, e−0.18 − 1). Event-study estimates are consistent with the internal validity of this inference in that we cannot reject the null hypothesis (P = 0.59) that pretreatment changes by period are the same across treatment and comparison neighbourhoods (Supplementary Table 5 and Supplementary Fig. 2). This result is also similar across different approaches to estimation and inference for count-based panel data (Supplementary Table 6) and under randomization inference (Supplementary Fig. 3).

The analytic sample consists of a balanced panel of 48 neighbourhoods over 54 months (N = 2,592). The reported estimates are based on conditional maximum likelihood Poisson specifications that include neighbourhood and month–year fixed effects. All tests of statistical significance are two-tailed. Bootstrapped standard errors are blocked at the neighbourhood level. Dots are point estimates; bars are 95% CIs. See Supplementary Table 3 for fully reported results.

Figure 1 also indicates that the estimated impact of the co-responder programme on programme-relevant emergency calls—and criminal offences and arrests on those calls—are negative but statistically insignificant. Before our analysis, we defined these programme-relevant calls as those with final designations entered by dispatchers or officers as involving mental health crises (including potential suicides), welfare checks and community disturbances. However, the descriptive data indicate that emergency calls related to general welfare checks and community disturbances are substantially more common than those involving a primary mental health component (Supplementary Table 1). Therefore, we conducted an exploratory analysis examining the impact of the co-responder programme on each type of emergency call. The results in Fig. 2 indicate that the co-responder programme led to a statistically significant reduction in emergency calls primarily related to mental health (b = −0.185, 95% CI −0.356 to −0.014, P = 0.0329) but had statistically insignificant effects on the broader set of calls related to welfare checks and community disturbances.

The analytic sample consists of a balanced panel of 48 neighbourhoods over 54 months (N = 2,592). The reported estimates are based on conditional maximum likelihood Poisson specifications that include neighbourhood and month–year fixed effects. All tests of statistical significance are two-tailed. Bootstrapped standard errors are blocked at the neighbourhood level. Dots are point estimates; bars are 95% CIs. See Supplementary Table 3 for fully reported results.

To place these results into perspective, we note that, in the 12 months before the CWCRT programme, 1,121 involuntary psychiatric detentions occurred in the four pilot communities. This implies that 2 years of pilot programme operations lowered the number of such detentions by 370 (that is, 1,121 × 0.165 × 2).

The costs of an involuntary psychiatric detention are difficult to identify precisely. Estimates of the cost of the initial emergency-department visit, adjusted to 2022 US dollars, vary from US$639 to US$3,217—with the higher value reflecting the often long ‘boarding time’ for individuals experiencing mental illness28,29. Additional costs occur when a detained individual is admitted to a hospital. The daily cost of an in-patient stay for a mental health or substance-abuse issue averages US$1,365 per day in 2022 US dollars12. Given that as few as 25% of detainees are hospitalized30,31,32, the 3-day hospitalization cost of a detention is US$1,024 in expectation. Taken together, this implies that the direct cost of an involuntary psychiatric detention to emergency departments and hospitals varies from US$1,663 to US$4,241 in 2022 US dollars. Given the estimated programme-induced reduction in involuntary psychiatric detentions (that is, 185 per year), this implies an annual health-cost savings ranging from roughly US$300,000 to US$800,000.

The second preregistered analysis focuses on binary indicators for the disposition of emergency calls (that is, involuntary psychiatric detention, criminal offence and arrest) identified by dispatchers as eligible for a co-responder. This incident-level analysis both provides alternative direct evidence on the impact of co-responders and indirect insights into whether their immediate impact of co-responders extends to reducing future incidents. Figure 3 presents the key results of the preregistered design that conditions on unrestricted fixed effects unique to each neighbourhood, each hour of the day, each day of the week and each month–year. These estimates indicate that the presence of a co-responder reduced that likelihood that the incident resulted in an involuntary psychiatric detention by a statistically significant 11.5 percentage points (b = −0.115, 95% CI −0.144 to −0.086, P < 0.0001). This estimated impact is large relative to the likelihood in the overall sample that a programme-eligible incident resulted in an involuntary psychiatric detention (that is, 16.5%; Supplementary Table 2). By contrast, the estimated effects of a co-responder on the likelihood of a recorded criminal offence or an arrest were smaller and statistically insignificant (Fig. 3).

The analytic sample includes 4,117 CWCRT-eligible calls for service in three participating cities over 25 months. The dependent variable is a binary indicator of whether an involuntary psychiatric detention was initiated as a result of the call for service. Independent variables include neighbourhood, month–year sequence, day of week and hour of day fixed effects. All tests of statistical significance are two-tailed. Dots are point estimates, and bars are 95% CIs. See Supplementary Table 6 for fully reported results.

To place this incident-level impact into perspective, we note that, over the first 25 months of the pilot period, co-responders participated in 1,577 emergency calls, or roughly 757 (that is, (1,577/25) × 12) co-responses per year. The implied, direct, incident-level impact of co-responders was to reduce the number of involuntary psychiatric detentions by 174 (that is, 757 × 0.115 × 2) over 2 years.

This pattern of results is robust in specifications saturated with additional fixed effects beyond those in the preregistered specification (Supplementary Table 8) and in specifications that correct for the tacit weighting that occurs in fixed-effect specifications (Supplementary Table 9). We also found similar results (Supplementary Table 10) across busy hours of the day and week and less busy times when the dispatcher assignment of a co-responder is more discretionary (that is, not constrained by their assignment to another call).

Discussion

This preregistered study provides credibly causal evidence on the incident- and community-level impacts of co-responder programmes that pair mental health professionals with police officers as first responders to qualified emergency calls. These results indicate that the co-responder programme’s overall effect was to reduce involuntary psychiatric detentions by 16.5% (or roughly 185 fewer detentions per year), implying an annual health cost savings ranging from US$300,000 to US$800,000. In the CWCRT context, these savings largely accrue to taxpayers, particularly local ones, whose contributions largely fund the County services (see ‘CWCRT programme description’ in Supplementary Information for details). While these cost-effectiveness estimates are illustrative, a more complete cost–benefit analysis would require longer-run data unavailable to us on additional costs of psychiatric detentions (for example, ambulance/police transportation and law enforcement officer salaries/overtime), any additional health costs associated with alternative services offered by the co-responder programme and the potential benefits of better-aligned health care.

The incident-level evidence from our second preregistered analysis also suggests the impact of co-responders on involuntary psychiatric detentions was substantial, reducing the likelihood that a given incident resulted in an involuntary psychiatric detention by 11.5 percentage points (or 87 fewer detentions per year). Because the overall impact of the co-responder programme during this period (that is, a reduction of 185 detentions annually) was approximately twice as large, these results are consistent with the hypothesis that co-responders influenced both the disposition of emergencies where they served as first responders and the prevalence of future emergencies. The exploratory evidence that the co-responder reduced the frequency of emergency calls where mental health was a primary factor (Fig. 2) is also consistent with this interpretation. Notably, one other study, which examines a related ‘community responder’ approach to qualified emergencies, finds similar evidence for such ‘spillover’ benefits33.

Regarding null effects on other confirmatory outcomes (that is, programme-related calls, criminal offences and arrests), we note that not all incidents coded as ‘CWCRT-related’ are likely to have a clear mental health component. Our choices in coding calls for service reflect the balance between our effort to bring preregistration to quasi-experimental studies like this and the challenges of doing so transparently when some degree of ex ante data processing and exploration is required34. Our pre-analysis definitions—based on calls related to welfare checks, community disturbances and mental health—reflect our best prior assessment of the alignment between call-type codes and the CWCRT’s theory of change35. However, the number of calls for community disturbances and welfare checks dramatically exceeds those identified as mental health calls (Supplementary Table 1). So, this pre-analysis designation may have been overly broad. Our exploratory results support this, suggesting that the introduction of the CWCRT programme is associated with a substantial reduction in emergency calls related to mental health (Fig. 2).

Finally, we note the study’s extant limitations. First, we underscore that data and temporal limitations constrain our ability to evaluate other outcomes of relevance—such as uptake of outpatient therapy, participation in governmental or nonprofit resource programmes, number of hours or days of hospitalization resulting from experiencing a mental health crisis, and long-term effects of the CWCRT programme for affected subjects. Furthermore, although this study exhibits a high degree of internal validity due to the use of a preregistered research design and strong robustness checks, we acknowledge limitations to external validity of our findings. Specifically, we caution overinterpretation of the potential replicability of findings when applied to other contexts.

Conclusion

This study provides encouraging early evidence on the impact of the recently proliferating reforms that seek to better serve individuals in mental health emergencies. In particular, these results are consistent with the hypothesis that the presence of mental health first responders on qualified emergency calls improves the alignment of appropriate health care for some individuals in crisis by reducing the prevalence of involuntary psychiatric detentions. Furthermore, our findings suggest that this effect occurs both in the immediate response to the emergency and in reducing the likelihood of future recurrences. These results provide motivation for the continued adoption and evaluation of such reforms across the USA. However, successfully replicating and scaling the promising evidence of an early pilot like CWCRT is likely to hinge on key design and implementation details. These include establishing new protocols for the triage and communication of emergency calls, training dispatchers, hiring appropriately trained mental health clinicians, ensuring the engaged participation of police officers and building community awareness. Although meeting those operational challenges is non-trivial, the early evidence on these reforms establishes that it is both feasible and effective.

Methods

This study was approved by Stanford University’s Institutional Review Board (protocol ID IRB-760) and was preregistered through the Open Science Framework on 16 March 2024 (https://osf.io/dbs35). For both the total-effects and incident-level effects research agendas, we received data transfers of incident-level emergency call for service and criminal complaint records by means of signed data-use agreements with the relevant governing bodies. Emergency call for service-dispatch records come from police agency regulatory information management systems in eight cities (that is, Belmont, Burlingame, Foster City, Menlo Park, Pacifica, City of San Mateo, South San Francisco and Redwood City) and from San Mateo County’s Public Safety Communications Division administrative records (which administers emergency dispatch on behalf of Daly City). These records contain information on types, dates and locations of emergency calls; whether a criminal complaint was opened and/or an involuntary psychiatric detention was implemented in response to a call; and the availability and dispatch of clinician co-responders to a call. Criminal complaint records come from regulatory information management systems in all nine police agencies and contain information on criminal offences and arrests associated with emergency calls for service. We retain recorded emergency dispatcher call for service incidents and resulting actions (for example, involuntary psychiatric detentions and criminal complaints) in each neighbourhood (that is, mutually exclusive and exhaustive police areas) in a given month over the first 25 months of the pilot programme operating. Below, we provide details on the procedures for defining the sample and analytic strategies in each of the two research agendas. We analyse all data using Stata statistical software (version 18), and all tests of statistical significance are two-tailed.

Total effects

In our total-effects research design, data come from incident-level emergency dispatcher calls for service provided by San Mateo County and/or police agencies in the four participating pilot cities (that is, Daly City, San Mateo, South San Francisco and Redwood City) and five comparison cities not participating in the programme (that is, Belmont, Burlingame, Foster City, Menlo Park and Pacifica). Due to data availability in the comparison cities at the time of preregistration, our focal timeframe and unit of analysis is programme-related calls for service per neighbourhood in 48 neighbourhoods (26 treatment, 22 comparison) among these 9 cities in San Mateo County, CA, over 54 months (that is, 2,592 neighbourhood observations from January 2019 through June 2023). This time period represents the first 19 months of the pilot phase of CWCRT up to the last round of full data collection available for all nine cities (December 2021 to June 2023) and the 3 years before the pilot beginning (January 2019 to November 2021). Our DiD design strategy allows us to take advantage of our panel dataset in months surrounding implementation.

Our primary outcomes of interest are neighbourhood–month counts of involuntary psychiatric detentions and programme-related calls for service, criminal offences and arrests recorded by dispatchers and police officers36. Using these aggregations of incident-level data, we first construct a simple binary treatment indicator, \({S}_{{at}}\), equal to 1 for neighbourhood–month observations from where and when CWCRT was active (that is, a ‘static’ measure of treatment). Supplementary Table 1 provides key descriptive statistics.

The baseline specification for identifying the programme impact takes the following form:

where \({Y}_{{at}}\) is the number of involuntary psychiatric detentions for neighbourhood a in time period t. The coefficient of interest, \(\theta\), represents the effect of the CWCRT programme conditional on fixed effects unique to each neighbourhood and to each month–year (that is, \({\alpha }_{a}\) and \({\gamma }_{t}\), respectively). The term \({\varepsilon }_{{at}}\) is a mean-zero error term with clustering at the neighbourhood level.

This DiD specification effectively considers the pre–post change in focal outcomes in neighbourhoods employing the CWCRT programme relative to contemporaneous changes in comparison neighbourhoods where services were not yet available. We note that there is no variation in treatment timing—each neighbourhood that participated in the CWCRT pilot began doing so at the same time.

Next, to test for time-varying treatment effects, we use a semi-dynamic DiD model that unrestrictedly allows for treatment effects unique to the month immediately after a neighbourhood first participates and in the proceeding months after treatment begins:

In this model, the coefficients of interest are represented by \({\delta }_{n}\), which identify the effects of CWCRT in the first month of the programme (that is, \({S}_{a,m-0}\)) as well as the current effect of having begun 1 month earlier (that is, \({S}_{a,m-1}\)), 2 months earlier (that is, \({S}_{a,m-2}\)) and so on. We then test the equivalence of these coefficients of interest using the null hypothesis of a constant treatment effect:

A causal interpretation of the confirmatory DiD estimates relies on the assumption that time-varying changes within comparison neighbourhoods serve as valid counterfactuals for what we would have expected to happen in treated neighbourhoods if not for the presence of the CWCRT programme. Supplementary Table 5 presents ‘event-study’ DiD estimates that provide evidence on this key assumption. This ‘parallel trends’ assumption is fundamentally untestable as it involves unobserved potential outcomes for the treated communities. However, we can provide empirical evidence on the validity of this important assumption through unrestrictive event-study specifications that allow us to examine whether treatment and comparison-group precincts had similar month-to-month changes in outcomes before the onset of treatment. To the extent that this hypothesis is true, it is consistent with the parallel-trends assumption. We examine this question through event-study specifications of the following form:

This event-study specification effectively allows for fixed effects unique to treated neighbourhoods in distinct months before and after participating in CWCRT (that is, ‘leads’ and ‘lags’ of treatment adoption). That means the coefficients of interest are represented as \({\delta }_{-n}\) and \({\delta }_{\tau }\), which designate the distinctive time-varying outcome changes in treated neighbourhoods in each of 12 months before programme implementation and in each period once the programme began, with the final indicator representing treated neighbourhoods 10 or more months after the programme began. The reference category includes those areas never participating in CWCRT and those in 13 or more months before their first participation in CWCRT. To examine the assumption of parallel trends, we test whether, before their participation in CWCRT, treatment precincts have month-to-month changes in outcomes distinct from comparison neighbourhoods:

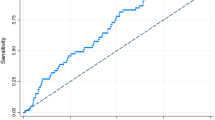

We report the key event-study results in Supplementary Fig. 2 and Supplementary Table 5. The results are broadly consistent with the parallel-trends assumption. For example, Supplementary Fig. 2 illustrates the event-study results for involuntary psychiatric detentions and suggests a noisy but flat trend before programme operation and a distinctive decline once programme operations began. In addition, the results in Supplementary Table 5 indicate that we cannot reject the null hypothesis that the treated precincts had month-to-month changes in involuntary psychiatric detentions similar to the comparison districts in the months before the programme activity (P = 0.57). We note that, for the other confirmatory outcomes (that is, total calls, offences and arrests on those calls), the validity of this modelling assumption is less clear. However, for the exploratory outcome where we find a statistically significant programme impact (that is, mental health calls), the event-study evidence is consistent with the parallel-trends assumption. That is, we cannot reject the null hypothesis of the joint statistical insignificance of pretreatment outcome trends unique to treatment communities (P = 0.44).

We also assess the robustness of our central confirmatory and exploratory DiD results (that is, programme effects on involuntary psychiatric detentions and mental health calls) to alternative approaches to estimation and inference. Specifically, Supplementary Table 6 reports similar results when using the negative-binomial version of a conditional maximum likelihood specification with bootstrapped standard errors that allow for neighbourhood clustering and in conditional maximum likelihood Poisson and negative-binomial specifications without clustering. We also find similar results in maximum-likelihood versions of Poisson and negative-binomial specifications that directly control for neighbourhood and month–year fixed effects through dummy variables, either with robust standard errors or with clustering at the neighbourhood level.

As an additional robustness check on our core confirmatory findings, we also examined a design-based approach to inference and found consistent results. Specifically, we conducted randomization inference for the estimated effect of co-responders on involuntary psychiatric detentions in the DiD (that is, total effect) specification. Under this approach, we randomly assigned treatment status, within neighbourhoods, to each observation and estimated the impact of this treatment status on the outcome 1,000 times. The resulting distributions of point estimates effectively provide sampling distributions under the null hypothesis of no treatment effect. The top panel of Supplementary Fig. 3 illustrates the distribution of these point estimates, with the vertical red line indicating the corresponding point estimate implied by the true treatment status of each observation (Supplementary Table 3). Notably, none of the 1,000 permutations produced a point estimate as large in absolute value as the actual point estimate, implying a randomization-inference P value of less than 0.001 and rejection of the null hypotheses of no treatment impact. We note that this design-based approach implies a substantial gain in the precision of this DiD estimate.

Incident-level effects

Our second preregistered research design isolates the incident-level effects of the CWCRT programme on involuntary psychiatric detentions for all reported incidents deemed ‘CWCRT-eligible’ by a dispatcher or police officer. Eligible calls are logged as such regardless of whether a clinician was available to respond to the incident. Our focal timeframe and unit of analysis is CWCRT-eligible calls for service from emergency dispatcher calls for service data provided by police agencies in three of the four cities participating in the CWCRT programme, from December 2021 through December 2023 (that is, 4,117 CWCRT-eligible calls for service over 25 months of programme implementation). We exclude data on one CWCRT participating city because, in that city, we only observe recorded reports of CWCRT eligibility if a clinician is available and responds to the call for service, and no information on eligible calls when a clinician is unavailable or off duty. Supplementary Table 2 presents key descriptive statistics for this analytical sample, differentiated by whether the incident received a CWCRT co-response.

Our main confirmatory design compares programme-eligible incidents receiving a CWCRT response with those eligible but not receiving a response (that is, due to a clinician being unavailable or off duty) conditional on unrestrictive covariates that control for factors unique to each neighbourhood and time of the incident37. Specifically, our baseline specification expresses the outcome for incident i, \({Y}_{{inhdt}}\), as a function of unrestrictive fixed effects for each neighbourhood, n; each hour of the day, h; each day of the week, d; and each month–year combination, t:

Our coefficient of interest, \(\beta\), identifies the effect of having co-responders dispatched to the incident (that is, \({C}_{{inhdt}}\)), conditional on these fixed effects.

We explore the robustness of results based on this design in several ways. One is to evaluate estimates of \(\beta\) in specifications saturated with increasingly unrestrictive sets of fixed effects (for example, for each unique neighbourhood–month–year combination, interaction of neighbourhood with day of the week and with the hour of the day, and interaction of month–year and day of week) in Supplementary Table 8. These increasingly saturated specifications consistently indicate a large, negative and statistically significant effect of co-responders on the likelihood of an involuntary psychiatric detention, although the magnitude of this estimate falls somewhat in the most saturated specifications. Second, we consider a reweighting approach (Supplementary Table 9) to assess the potential bias that can occur in fixed-effect specifications due to the tacit weighting that occurs when there is variation in the number of observations and the conditional variance of treatment within ‘cells’ defined by fixed effects37. Those results indicate that reweighted estimates are quite similar to those we report. Third, we conduct randomization inference for the estimated effect of co-responders on involuntary psychiatric detentions in our confirmatory fixed-effects design (Supplementary Fig. 3). We again found that none of 1,000 permutations where treatment status was randomly assigned within neighbourhoods returned a point estimate as large as the confirmatory result based on our preregistered specification, implying a randomization-inference P value less than 0.001.

Given that, within eligible incidents, the assignment of co-responders could relate to unobserved traits of an incident (and the related dispatcher discretion), we cannot be entirely certain about the potential internal-validity threats (that is, a caveat relevant to all quasi-experimental studies). However, we emphasize five factors that strengthen our confidence in the reliability of the incident-level results. First (and most importantly), the likely direction of omitted variable biases implies that, if anything, our findings would understate the impact of co-responders in reducing the chance that an incident results in a psychiatric detention. This is because, when faced with a choice informed by unobserved factors, a co-responder is more likely to be dispatched to a more serious incident with a clear mental health component (that is, cases with an unobserved propensity for a detention). Second, the complementary evidence from the total-effects DiD design suggests the reliability of the incident-level results. Third, we believe our fairly unique use of quasi-experimental design preregistration adds to the reliability of these findings. Fourth, our study underscores important and supportive empirical evidence (that is, the robustness of the findings to increasingly saturated fixed effects that are beyond our preregistered confirmatory specification). Fifth, we also present empirical evidence on how the frequency of programme-eligible calls varied across CWCRT’s operating hours.

Deviations from the preregistration protocol

There are seven deviations from the preregistration protocol that are reported in this Article. First, the opening paragraph of the preregistration protocol incorrectly identifies six comparison cities. Although we initially intended to include data from six neighbouring comparison cities, one of those cities was not able to share their data with us by the time of filing the preregistration protocol and was thus not considered for analysis.

Second, there is a typographical error in the preregistration protocol that claimed the incident-level sample size is 4,118. The actual incident-level sample size is in fact 4,117.

Third, the preregistration protocol indicates that treatment months began in January 2022; however, the sample reported in the preregistration and the main text of the paper in fact include some co-responding incidents that occurred in December 2021 as well. This reflects an error in reporting the timeframe of the treatment period and not a change in the reported sample size.

Fourth, the preregistration protocol states that the data include only information involving adults. The programme does in fact serve adults and minors, and the preregistered sample reflects that.

Fifth, in response to reviewer comments, we have added exploratory analyses examining the effects of co-responder assignment across more and less busy hours of the day using the criteria above and found only a slight and statistically insignificant increase in the co-responder’s effect on reductions in involuntary psychiatric detentions during busier periods (Supplementary Table 10).

Sixth, the preregistration protocol indicates that we will identify programme-relevant offences and arrests using an adapted coding structure from a prior study33. However, because domain outcome A1 is defined by identifying programme-relevant calls (which may not result in an offence or an arrest and is closely aligned with the programme’s theory of change), we instead used this definition across calls, offences and arrests. Critically, these changes were made before our analysis of outcomes. However, we note that, when using the prior coding scheme implied in the preregistration for offences and arrest outcomes, we find similar null results (Supplementary Table 11).

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The data we use are city and county administrative records that include detailed information on individuals who are experiencing a mental health crisis and facing potential criminal charges. Applicants can request access to the following data sources listed below: Belmont, CA calls-for-service and criminal offence records: police@belmont.gov. Burlingame, CA calls-for-service and criminal offence records: clerks@burlingamepolice.org. City of San Mateo, CA calls-for-service and criminal offence records: police@cityofsanmateo.org. Daly City, CA criminal offence records: (650) 991-8119. Daly City, CA call-for-service records: smcdispatch@smcgov.org. Foster City, CA calls-for-service and criminal offence records: policechief@fostercity.org. Menlo Park, CA calls-for-service and criminal offence records: (650) 330-6600. Pacifica, CA calls-for-service and criminal offence records: police@pacificapolice.org. Redwood City, CA calls-for-service and criminal offence records: rcpd@redwoodcity.org. South San Francisco, CA calls-for-service and criminal offence records: (650) 877-8500. Geographic information system data used to create Supplementary Fig. 1 were retrieved and adapted from public-use records provided by the County of San Mateo, CA, and can be found at https://www.smcgov.org/isd/gis.

References

Dahlberg, B. Rochester Hospital released Daniel Prude hours before fatal encounter with police. National Public Radio (29 September 2020).

Elfrink, T. ‘He’s a small child’: Utah Police shot a 13-year-old boy with autism after his mother called 911 for help. The Washington Post (8 September 2020).

Lum, C., Koper, C. S. & Wu, X. Can we really defund the police? A nine-agency study of police response to calls for service. Police Quart. 25, 255–280 (2021).

Strahan, T. & Novini, R. Family demands answers after man killed by Jersey City Police amid mental health crisis. NBC News (28 August 2023).

The Associated Press Three San Antonio police officers charged with murder after killing of woman in middle of ‘mental health crisis’. NBC News (24 June 2023).

Lum, C. Perspectives on policing: Cynthia Lum. Annu. Rev. Criminol. 4, 19–25 (2021).

Cohen, G. & Bagwell, M. The state of mental health training in basic police curricula: a national level examination. J. Public Aff. Educ. 29, 327–349 (2023).

Suslovic, B. Encyclopedia of Social Work (Oxford Univ. Press, 2024).

Saya, A. et al. Criteria, procedures, and future prospects of involuntary treatment in psychiatry around the world: a narrative review. Front. Psychiatry 10, 1–22 (2019).

Morris, N. P. Reasonable or random: 72-hour limits to psychiatric holds. Psychiatr. Serv. 72, 210–212 (2021).

Miller, D. & Hanson, A. Committed: The Battle Over Involuntary Psychiatric Care (JHU Press, 2016).

Morris, N. P. & Kleinman, R. A. Involuntary commitments: billing patients for forced psychiatric care. Am. J. Psychiatry 177, 1115–1116 (2020).

Borecky, A., Thomsen, C. & Dubov, A. Reweighing the ethical tradeoffs in the involuntary hospitalization of suicidal patients. Am. J. Bioeth. 19, 71–83 (2019).

Priebe, S. Involuntary hospitalization of suicidal patients: time for new answers to basic questions?. Am. J. Bioeth. 19, 90–92 (2019).

Lee, G. & Cohen, D. Incidences of involuntary psychiatric detentions in 25 US states. Psychiatr. Serv. 72, 61–68 (2021).

McGarvey, E. L., Leon-Verdin, M., Wanchek, T. N. & Bonnie, R. J. Decisions to initiate involuntary commitment: the role of intensive community services and other factors. Psychiatr. Serv. 64, 120–126 (2013).

Walker, S. et al. Clinical and social factors associated with increased risk for involuntary psychiatric hospitalisation: a systematic review, meta-analysis, and narrative synthesis. Lancet Psychiatry 6, 1039–1053 (2019).

Wood, J. D. & Watson, A. C. Improving police interventions during mental health-related encounters: past, present and future. Polic. Soc. 27, 289–299 (2017).

Jones, N. et al. Youths’ and young adults’ experiences of police involvement during initiation of involuntary psychiatric holds and transport. Psychiatr. Serv. 73, 910–917 (2022).

Katsakou, C. & Priebe, S. Outcomes of involuntary hospital admission—a review. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 114, 232–241 (2006).

Wahbi, R. & Beletsky, L. Involuntary commitment as ‘carceral-health service’: from healthcare-to-prison pipeline to a public health abolition praxis. J. Law Med. Ethics 50, 23–30 (2022).

Wood, J., Swanson, J. W., Burris, S. & Gilbert, A. Police Interventions With Persons Affected by Mental Illnesses: A Critical Review of Global Thinking and Practice (Center for Public Health Law Research, 2011).

Morris, N. P. Detention without data: public tracking of civil commitment. Psychiatr. Serv. 71, 741–744 (2020).

Morris, N. P. & Kleinman, R. A. Taking an evidence-based approach to involuntary psychiatric hospitalization. Psychiatr. Serv. 74, 431–433 (2023).

Shapiro, G. K. et al. Co-responding police-mental health programs: a review. Adm. Policy Ment. Health Ment. Health Serv. Res. 42, 606–620 (2015).

The Value of Partnership: How Colorado's Co-Responder Programs Enhance Access to Behavioral Health Care (Colorado Health Institute, 2021).

Childs, K. K., Elligson, R. L. & Brady, C. M. Testing the impact of a law enforcement–operated co-responder program for youths: a quasi-experimental approach. Psychiatr. Serv. 75, 1213–1219 (2024).

Dee, T. S. & Pyne, J. Technical Report: Two Distinct Quasi-Experimental Approaches for Evaluating the Causal Effects of the Community Wellness and Crisis Response Team Pilot Program (The John W. Gardner Center for Youth and their Communities at Stanford University, 2024).

Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2020).

Barnard, A. V. Conservatorship: Inside California’s System of Coercion and Care for Mental Illness (Columbia Univ. Press, 2023).

Nordstrom, K. et al. Boarding of mentally ill patients in emergency departments: American Psychiatric Association Resource Document. West. J. Emerg. Med. 20, 690–695 (2019).

Zeller, S., Calma, N. & Stone, A. Effects of a dedicated regional psychiatric emergency service on boarding of psychiatric patients in area emergency departments. West. J. Emerg. Med. 15, 1–6 (2014).

Dee, T. S. & Pyne, J. A community response approach to mental health and substance abuse crises reduced crime. Sci. Adv. 8, eabm2106 (2022).

Dee, T. S. The case for preregistering quasi-experimental program and policy evaluations. Eval. Rev. 49, 931–945 (2025).

The John W. Gardner Center for Youth and their Communities Research Brief: Pilot Program Theory of Change, The Community Wellness and Crisis Response Team of San Mateo County, California (Stanford Univ., 2024).

Chen, J. & Roth, J. Logs with zeros? Some problems and solutions. Quart. J. Econ. 139, 891–936 (2023).

Gibbons, C. E., Serrato, J. C. S. & Urbancic, M. B. Broken or fixed effects?. J. Econometr. Methods 8, 20170002 (2019).

Acknowledgements

We thank leaders in the County of San Mateo, StarVista, Stanford’s John W. Gardner Center for Youth and their Communities, the four participating police agencies (that is, Daly City, City of San Mateo, South San Francisco and Redwood City) and five non-participating police agencies (that is, Belmont, Burlingame, Foster City, Menlo Park and Pacifica) for participating in this research and sharing relevant administrative records. Funding for the study has been provided by Arnold Ventures (23-09505; T.S.D. and J.P.) and the County of San Mateo. The funders had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: T.S.D. and J.P. Methodology: T.S.D. and J.P. Investigation: T.S.D. and J.P. Visualization: T.S.D. and J.P. Writing—original draft: T.S.D. and J.P. Writing—review and editing: T.S.D. and J.P.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Human Behaviour thanks Rebecca Johnson, Yi-Fang Lu and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

CWCRT programme description, Supplementary Figs. 1–3, Supplementary Tables 1–11 and CWCRT preregistration protocol.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Dee, T.S., Pyne, J. Emergency mental health co-responders reduce involuntary psychiatric detentions in the USA. Nat Hum Behav 10, 148–155 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-025-02339-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-025-02339-7