Abstract

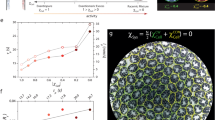

During wound repair, branching morphogenesis and carcinoma dissemination, cellular rearrangements are fostered by a solid-to-liquid transition, known as unjamming. The biomolecular machinery behind unjamming and its pathophysiological relevance remain, however, unclear. Here, we study unjamming in a variety of normal and tumorigenic epithelial two-dimensional (2D) and 3D collectives. Biologically, the increased level of the small GTPase RAB5A sparks unjamming by promoting non-clathrin-dependent internalization of epidermal growth factor receptor that leads to hyperactivation of the kinase ERK1/2 and phosphorylation of the actin nucleator WAVE2. This cascade triggers collective motility effects with striking biophysical consequences. Specifically, unjamming in tumour spheroids is accompanied by persistent and coordinated rotations that progressively remodel the extracellular matrix, while simultaneously fluidizing cells at the periphery. This concurrent action results in collective invasion, supporting the concept that the endo-ERK1/2 pathway is a physicochemical switch to initiate collective invasion and dissemination of otherwise jammed carcinoma.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$32.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $21.58 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

The authors declare that all data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper and its supplementary Information files and from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

Code availability

The codes used for the analysis are all indicated in the Methods.

Change history

27 September 2022

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41563-022-01365-4

References

Hakim, V. & Silberzan, P. Collective cell migration: a physics perspective. Rep. Prog. Phys. 80, 076601 (2017).

Haeger, A., Wolf, K., Zegers, M. M. & Friedl, P. Collective cell migration: guidance principles and hierarchies. Trends Cell Biol. 25, 556–566 (2015).

Park, J. A., Atia, L., Mitchel, J. A., Fredberg, J. J. & Butler, J. P. Collective migration and cell jamming in asthma, cancer and development. J. Cell Sci. 129, 3375–3383 (2016).

Bi, D., Yang, X., Marchetti, M. C. & Manning, M. L. Motility-driven glass and jamming transitions in biological tissues. Phys. Rev. X 6, 021011 (2016).

Sadati, M., Taheri Qazvini, N., Krishnan, R., Park, C. Y. & Fredberg, J. J. Collective migration and cell jamming. Differentiation 86, 121–125 (2013).

Atia, L. et al. Geometric constraints during epithelial jamming. Nat. Phys. 14, 613–620 (2018).

Garcia, S. et al. Physics of active jamming during collective cellular motion in a monolayer. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 112, 15314–15319 (2015).

Oswald, L., Grosser, S., Smith, D. M. & Kas, J. A. Jamming transitions in cancer. J. Phys. D 50, 483001 (2017).

Haeger, A., Krause, M., Wolf, K. & Friedl, P. Cell jamming: collective invasion of mesenchymal tumor cells imposed by tissue confinement. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1840, 2386–2395 (2014).

Sigismund, S. & Scita, G. The ‘endocytic matrix reloaded’ and its impact on the plasticity of migratory strategies. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 54, 9–17 (2018).

Corallino, S., Malabarba, M. G., Zobel, M., Di Fiore, P. P. & Scita, G. Epithelial-to-mesenchymal plasticity harnesses endocytic circuitries. Front. Oncol. 5, 45 (2015).

Palamidessi, A. et al. Endocytic trafficking of Rac is required for the spatial restriction of signaling in cell migration. Cell 134, 135–147 (2008).

Frittoli, E. et al. A RAB5/RAB4 recycling circuitry induces a proteolytic invasive program and promotes tumor dissemination. J. Cell Biol. 206, 307–328 (2014).

Malinverno, C. et al. Endocytic reawakening of motility in jammed epithelia. Nat. Mater. 16, 587–596 (2017).

Giavazzi, F. et al. Giant fluctuations and structural effects in a flocking epithelium. J. Phys. D 50, 384003 (2017).

Giavazzi, F. et al. Flocking transitions in confluent tissues. Soft Matter 14, 3471–3477 (2018).

Mendoza, M. C. Phosphoregulation of the WAVE regulatory complex and signal integration. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 24, 272–279 (2013).

Debnath, J., Muthuswamy, S. K. & Brugge, J. S. Morphogenesis and oncogenesis of MCF-10A mammary epithelial acini grown in three-dimensional basement membrane cultures. Methods 30, 256–268 (2003).

Levitzki, A. & Gazit, A. Tyrosine kinase inhibition: an approach to drug development. Science 267, 1782–1788 (1995).

Lang, E. et al. Coordinated collective migration and asymmetric cell division in confluent human keratinocytes without wounding. Nat. Commun. 9, 3665 (2018).

Zeigerer, A. et al. Rab5 is necessary for the biogenesis of the endolysosomal system in vivo. Nature 485, 465–470 (2012).

Kirchhausen, T., Owen, D. & Harrison, S. C. Molecular structure, function, and dynamics of clathrin-mediated membrane traffic. Cold Spring Harbor Perspect. Biol. 6, a016725 (2014).

Sigismund, S. et al. Clathrin-mediated internalization is essential for sustained EGFR signaling but dispensable for degradation. Dev. Cell 15, 209–219 (2008).

Johannes, L., Parton, R. G., Bassereau, P. & Mayor, S. Building endocytic pits without clathrin. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 16, 311–321 (2015).

Caldieri, G. et al. Reticulon 3-dependent ER-PM contact sites control EGFR nonclathrin endocytosis. Science 356, 617–624 (2017).

Koivusalo, M. et al. Amiloride inhibits macropinocytosis by lowering submembranous pH and preventing Rac1 and Cdc42 signaling. J. Cell Biol. 188, 547–563 (2010).

Di Guglielmo, G. M., Baass, P. C., Ou, W. J., Posner, B. I. & Bergeron, J. J. Compartmentalization of SHC, GRB2 and mSOS, and hyperphosphorylation of Raf-1 by EGF but not insulin in liver parenchyma. EMBO J. 13, 4269–4277 (1994).

Vieira, A. V., Lamaze, C. & Schmid, S. L. Control of EGF receptor signaling by clathrin-mediated endocytosis. Science 274, 2086–2089 (1996).

McDonald, P. H. et al. Beta-arrestin 2: a receptor-regulated MAPK scaffold for the activation of JNK3. Science 290, 1574–1577 (2000).

Villaseñor, R., Nonaka, H., Del Conte-Zerial, P., Kalaidzidis, Y. & Zerial, M. Regulation of EGFR signal transduction by analogue-to-digital conversion in endosomes. eLife 4, e06156 (2015).

Barrett, S. D. et al. The discovery of the benzhydroxamate MEK inhibitors CI-1040 and PD 0325901. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 18, 6501–6504 (2008).

Kirchhausen, T., Macia, E. & Pelish, H. E. Use of dynasore, the small molecule inhibitor of dynamin, in the regulation of endocytosis. Methods Enzymol. 438, 77–93 (2008).

Komatsu, N. et al. Development of an optimized backbone of FRET biosensors for kinases and GTPases. Mol. Biol. Cell 22, 4647–4656 (2011).

Itoh, F. et al. The FYVE domain in Smad anchor for receptor activation (SARA) is sufficient for localization of SARA in early endosomes and regulates TGF-β/Smad signalling. Genes Cells 7, 321–331 (2002).

Farooqui, R. & Fenteany, G. Multiple rows of cells behind an epithelial wound edge extend cryptic lamellipodia to collectively drive cell-sheet movement. J. Cell Sci. 118, 51–63 (2005).

Alekhina, O., Burstein, E. & Billadeau, D. D. Cellular functions of WASP family proteins at a glance. J. Cell Sci. 130, 2235–2241 (2017).

Mendoza, M. C. et al. ERK-MAPK drives lamellipodia protrusion by activating the WAVE2 regulatory complex. Mol. Cell 41, 661–671 (2011).

Innocenti, M. et al. Abi1 is essential for the formation and activation of a WAVE2 signalling complex. Nat. Cell Biol. 6, 319–327 (2004).

Steffen, A. et al. Sra-1 and Nap1 link Rac to actin assembly driving lamellipodia formation. EMBO J. 23, 749–759 (2004).

Ewald, A. J., Brenot, A., Duong, M., Chan, B. S. & Werb, Z. Collective epithelial migration and cell rearrangements drive mammary branching morphogenesis. Dev. Cell 14, 570–581 (2008).

Kim, H. Y. & Nelson, C. M. Extracellular matrix and cytoskeletal dynamics during branching morphogenesis. Organogenesis 8, 56–64 (2012).

Carey, S. P., Martin, K. E. & Reinhart-King, C. A. Three-dimensional collagen matrix induces a mechanosensitive invasive epithelial phenotype. Sci. Rep. 7, 42088 (2017).

Nguyen-Ngoc, K. V. et al. ECM microenvironment regulates collective migration and local dissemination in normal and malignant mammary epithelium. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 109, E2595–E2604 (2012).

Miller, F. R., Santner, S. J., Tait, L. & Dawson, P. J. MCF10DCIS.com xenograft model of human comedo ductal carcinoma in situ. J. Natl Cancer Inst. 92, 1185–1186 (2000).

Dvorak, H. F. Tumors: wounds that do not heal. Similarities between tumor stroma generation and wound healing. N. Engl. J. Med. 315, 1650–1659 (1986).

Vader, D., Kabla, A., Weitz, D. & Mahadevan, L. Strain-induced alignment in collagen gels. PLoS ONE 4, e5902 (2009).

Storm, C., Pastore, J. J., MacKintosh, F. C., Lubensky, T. C. & Janmey, P. A. Nonlinear elasticity in biological gels. Nature 435, 191–194 (2005).

Munster, S. et al. Strain history dependence of the nonlinear stress response of fibrin and collagen networks. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 110, 12197–12202 (2013).

Staneva, R., Barbazan, J., Simon, A., Vignjevic, D. M. & Krndija, D. Cell migration in tissues: explant culture and live imaging. Methods Mol. Biol. 1749, 163–173 (2018).

Yang, P. S. et al. Rab5A is associated with axillary lymph node metastasis in breast cancer patients. Cancer Sci. 102, 2172–2178 (2011).

Das, T. et al. A molecular mechanotransduction pathway regulates collective migration of epithelial cells. Nat. Cell Biol. 17, 276–287 (2015).

Mongera, A. et al. A fluid-to-solid jamming transition underlies vertebrate body axis elongation. Nature 561, 401–405 (2018).

Dang, T. T., Esparza, M. A., Maine, E. A., Westcott, J. M. & Pearson, G. W. ΔNp63α promotes breast cancer cell motility through the selective activation of components of the epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition program. Cancer Res. 75, 3925–3935 (2015).

Innocenti, M. et al. Abi1 regulates the activity of N-WASP and WAVE in distinct actin-based processes. Nat. Cell Biol. 7, 969–976 (2005).

Stradal, T. E. et al. Regulation of actin dynamics by WASP and WAVE family proteins. Trends Cell Biol. 14, 303–311 (2004).

Barry, D. J., Durkin, C. H., Abella, J. V. & Way, M. Open source software for quantification of cell migration, protrusions, and fluorescence intensities. J. Cell Biol. 209, 163–180 (2015).

Kardash, E., Bandemer, J. & Raz, E. Imaging protein activity in live embryos using fluorescence resonance energy transfer biosensors. Nat. Protoc. 6, 1835–1846 (2011).

Yang, Y. L., Leone, L. M. & Kaufman, L. J. Elastic moduli of collagen gels can be predicted from two-dimensional confocal microscopy. Biophys. J. 97, 2051–2060 (2009).

Beznoussenko, G. V., Ragnini-Wilson, A., Wilson, C. & Mironov, A. A. Three-dimensional and immune electron microscopic analysis of the secretory pathway in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Histochem. Cell Biol. 146, 515–527 (2016).

Beznoussenko, G. V. & Mironov, A. A. Correlative video-light-electron microscopy of mobile organelles. Methods Mol. Biol. 1270, 321–346 (2015).

Park, J. A. et al. Unjamming and cell shape in the asthmatic airway epithelium. Nat. Mater. 14, 1040–1048 (2015).

Pastore, R., Pesce, G. & Caggioni, M. Differential variance analysis: a direct method to quantify and visualize dynamic heterogeneities. Sci. Rep. 7, 43496 (2017).

Barron, J. L., Fleet, D. J. & Beauchemin, S. S. Performance of optical flow techniques. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 12, 43–77 (1994).

Kubo, R. The fluctuation-dissipation theorem. Rep. Prog. Phys. 29, 255–284 (1966).

Castro, A. P. et al. Combined numerical and experimental biomechanical characterization of soft collagen hydrogel substrate. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med. 27, 79 (2016).

Acknowledgements

This work has been supported by: the Associazione Italiana per la Ricerca sul Cancro (AIRC) to G.S. (IG#18621), P.P.D.F (IG#18988 and MCO 10.000), and F.G. (MFAG#22083); the Italian Ministry of University and Scientific Research (MIUR) to P.P.D.F. and G.S. (PRIN: PROGETTI DI RICERCA DI RILEVANTE INTERESSE NAZIONALE – Bando 2017#2017HWTP2K); the Italian Ministry of Health (RF-2013-02358446) to G.S. Regione Lombardia and CARIPLO foundation (Project 2016-0998) to R.C.; Worldwide Cancer Research (WCR#16-1245) to S.S. C.M. and F.G. are partially supported by fellowships from the University of Milan, E.B. from the FIRC-AIRC. We thank J. Christian (Max Planck Institute for Medical Research, Heidelberg, Germany) for help with fluorescent beads.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.P., C.M. and E.F. designed and performed all the experiments and edited the manuscript. S.C. aided in generating cell lines and in the analysis of immunofluorescence and kinematic studies. E.B., S.S. and P.P.F.D. conceived the internalization assays and interpreted the trafficking results. G.V.B. performed EM studies. E.M., M.G. and D.P. aided in all the imaging acquisition, FRET and PIV analysis. C.T aided in the analysis of RAB5A expression in breast cancer. Q.L. and F.A. performed and analysed the AFM measurements. F.G. and R.C. analysed all the kinematic data, developed the tools for 3D motility and mechanical analysis, edited the manuscript and conceived part of the study together with C.M. E.A.C.-A helped in setting up the fluorescent bead assay. G.S. conceived the whole study, wrote the manuscript and supervised all the work. C.M., F.G., R.C. and G.S. are all equally responsible for this work.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figs. 1–12, Supplementary Tables 1–4, Supplementary Video Legends 1–29, Supplementary Discussion and Supplementary references 1–19

Supplementary Video 1

RAB5A reawakening of collective motion in jammed epithelial monolayers depends on EGF

Supplementary Video 2

RAB5A reawakening of collective motion in jammed epithelial monolayers depends on EGFR

Supplementary Video 3

EGF-dependence of RAB5A flocking motility in EGFP-H2B-jammed epithelia monolayers

Supplementary Video 4

PIV analysis of EGF and EGFR-dependent endocytic unjamming

Supplementary Video5

RAB5A flocking motion in jammed epithelia is reduced by silencing Dynamin 2

Supplementary Video 6

RAB5A flocking motion in jammed epithelia is reduced by silencing RTN3, but not RTN4

Supplementary Video 7

RAB5A, but neither RAB5B nor RAB5C induces flocking motion in jammed epithelia

Supplementary Video 8

Flocking motion is abrogated by treatment with inhibitors of the MAPK/ERK1/2 pathway

Supplementary Video 9

Flocking motion is abrogated by treatment with Dynasore

Supplementary Video 10

MEK-DD is not sufficient to reawaken collective motion in jammed MCF10A monolayers

Supplementary Video 11

RAB5A-induced cryptic lamellipodia is compromised by treatment with MEK1/2 inhibitor

Supplementary Video 12

RAB5A-induced cryptic lamellipodia are inhibited by silencing the WAVE complex

Supplementary Video 13

RAB5A reawakening of collective motion in jammed epithelia is impaired by silencing NAP1

Supplementary Video 14

Silencing of NAP1 or WAVE2 affects RAB5A-induced wound closure in epithelial monolayers

Supplementary Video 15

Acini kinematic motility assay

Supplementary Video 16

PIV analysis on acini motility

Supplementary Video 17

RAB5A-mediated unjamming in MCF10A acini is trafficking-, EGFR- and ERK1/2-dependent

Supplementary Video 18

RAB5A-induced angular motion of MCF10A is independent of cell proliferation

Supplementary Video 19

RAB5A overcomes kinetic arrest of differentiated MCF10A acini

Supplementary Video 20

RAB5A reawakens collective motion in jammed MCF10.DCIS.com carcinoma cells

Supplementary Video 21

RAB5A promotes wound closure and flocking motion

Supplementary Video 22

RAB5A-mediated unjamming induces coordinated angular rotation in breast cancer spheroids

Supplementary Video 23

3D DVA of a RAB5A rotating spheroid after removal of the global rotation

Supplementary Video 24

RAB5A-flocking in spheroids is trafficking-, EGFR-, ERK1/2- and ARP2/3-dependent

Supplementary Video 25

RAB5A-mediated 3D unjamming promotes collective invasion in tumour spheroids

Supplementary Video 26

RAB5A spheroids exert larger stresses on surrounding ECM

Supplementary Video 27

Instantaneous velocity and stress maps of control and RAB5A-expressing spheroids.

Supplementary Video 28

RAB5A-mediated flocking promotes collective invasion in ex vivo DCIS tumour slices

Supplementary Video 29

PIV analysis on ex vivo DCIS tumour slice motility

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Palamidessi, A., Malinverno, C., Frittoli, E. et al. Unjamming overcomes kinetic and proliferation arrest in terminally differentiated cells and promotes collective motility of carcinoma. Nat. Mater. 18, 1252–1263 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41563-019-0425-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41563-019-0425-1

This article is cited by

-

Laminin-defined mechanical status modulates retinal pigment epithelium phagocytosis

EMBO Reports (2025)

-

BARCODE: high throughput screening and analysis of soft active materials

Nature Communications (2025)

-

The role of extracellular matrix viscoelasticity in development and disease

npj Biological Physics and Mechanics (2025)

-

Collective cell migration modes in development, tissue repair and cancer

Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology (2025)

-

Single-cell migration along and against confined haptotactic gradients

Nature Physics (2025)