Abstract

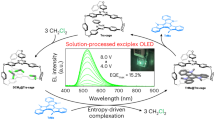

Charge-transfer (CT) complexes, formed by electron transfer from a donor to an acceptor, play a crucial role in organic semiconductors. Excited-state CT complexes, termed exciplexes, harness both singlet and triplet excitons for light emission, and are thus useful for organic light-emitting diodes (OLEDs). However, present exciplex emitters often suffer from low photoluminescence quantum efficiencies (PLQEs), due to limited control over the relative orientation, electronic coupling and non-radiative recombination channels of the donor and acceptor subunits. Here, we use a rigid linker to control the spacing and relative orientation of the donor and acceptor subunits, as demonstrated with a series of intramolecular exciplex emitters based on 10-phenyl-9,10-dihydroacridine and 2,4,6-triphenyl-1,3,5-triazine. Sky-blue OLEDs employing one of these emitters achieve an external quantum efficiency (EQE) of 27.4% at 67 cd m−2 with only minor efficiency roll-off (EQE = 24.4%) at a higher luminous intensity of 1,000 cd m−2. As a control experiment, devices using chemically and structurally related but less rigid emitters reach substantially lower EQEs. These design rules are transferrable to other donor/acceptor combinations, which will allow further tuning of emission colour and other key optoelectronic properties.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Light emission from an excited complex (exciplex) was first reported by Weller and colleagues in the early 1960s1,2,3. These charge-transfer (CT) complexes formed by a donor/acceptor (D/A) pair had a characteristic broad and structureless emission spectrum. It has, however, only recently been discovered that exciplexes, with their spatially separated electron and hole wavefunctions, can allow for very small energy differences between the lowest energy singlet and triplet excited states (ΔEST). These small energy splittings are a prerequisite for efficient thermally activated delayed fluorescence (TADF), such as the reverse intersystem crossing (RISC) of non-emissive triplet states into emissive singlets4.

Thanks to the TADF mechanism and the development of suitable D/A pairs, organic light-emitting diodes (OLEDs) based on exciplexes have reached impressive external quantum efficiencies (EQEs) exceeding 16% during the past few years5. However, the device performance of exciplex-based OLEDs still falls far behind that of devices utilizing conventional conjugated donor–π–acceptor (D–π–A)-type TADF materials or phosphorescent emitters6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18. The inferior electroluminescence efficiency of exciplex-based OLEDs is associated with their lower photoluminescence quantum efficiencies (PLQEs), which is a long-standing and unsolved issue in such systems5. In comparison to the ‘intramolecular’ CT states that are typical of TADF materials, the CT states in exciplex systems are ‘intermolecular’ in nature11,19. Thus, there are substantially more degrees of freedom that need to be finely controlled to enable efficient exciplex emission.

One of the most critical parameters for efficient exciplex formation is the distance between the D and A species. If the separation is too large, for example, in dilute solutions of D/A mixtures, the exciplex emission becomes negligible20,21. A possible solution to this challenge is to combine the D and A moieties in one molecule via a non-conjugated σ-spacer of variable lengths, forming a donor–σ–acceptor (D–σ–A) structure with an intramolecular exciplex-like electronic state22. However, although the spatial separation of the electron and hole wavefunctions resulted in a small ΔEST, the reported D–σ–A patterns did not resolve the problem of comparably low PLQEs23,24,25,26,27. This was mainly ascribed to the lack of control over the relative orientation of the donor and acceptor moieties in solid films, resulting in pronounced non-radiative decay losses22,28,29. Consequently, more attention needs to be paid to strengthening the D/A interactions while locking the donor and acceptor subunits into a rigid conformation.

Here, we present a molecular design strategy that operates via a space-confined CT (SCCT) to enhance the light emission from exciplex-type TADF emitters. We connect the donor and acceptor units via a rigid linker, thereby confining them into a closely packed coplanar configuration (Fig. 1a). The electronic coupling between the donor and acceptor units is sufficient to allow for efficient direct absorption by the CT state. In contrast to more flexible or less strongly coupled reference samples, the rigid exciplex emitters possess very high PLQEs of more than 90% when incorporated in a solid matrix, as well as faster RISC rates than conventional π-linked TADF molecules with a comparable ΔEST (ref. 30). OLEDs based on our champion material achieve an EQE of 27.4% at 67 cd m−2 with only minor efficiency roll-off (EQE = 24.4%) at a higher luminous intensity of 1,000 cd m−2. These results confirm that our SCCT design strategy provides a viable solution for overcoming the limitations of previous exciplex emitters. We are confident that the design rules developed here are transferrable to other D/A combinations and will provide further possibilities for tuning key optoelectronic properties, such as the emission colours of next-generation OLEDs.

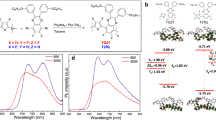

a, Illustration of the different donor/acceptor (D/A) designs explored in this study. b, Chemical structures of DM-B, DM-Bm, DM-G, DM-X and DM-Z and their molecular counterparts (DMTPA donor and TPZ acceptor). c, Normalized absorption (room temperature, 1 × 10−5 M in DCM) and fluorescence and phosphorescence emission spectra (77 K, 1 × 10−5 M in toluene) of the rigid exciplex emitters. Insets, single-crystal X-ray structures of DM-B, DM-Bm and DM-G.

Molecular design and photophysical properties

We started our search for highly luminescent intramolecular exciplex-type TADF emitters by designing a series of through-space CT molecules, across which we systematically vary the rigidity of the linker unit and the D/A distance (Fig. 1a,b). We chose 10-phenyl-9,10-dihydroacridine and 2,4,6-triphenyl-1,3,5-triazine as the donor and acceptor motifs, respectively. The first subset of molecules consists of cofacially arranged D/A dimers that are connected via a rigid fluorene linker: DM-B and DM-Bm (please refer to the Supplementary Information for the IUPAC names of the compounds) are closely packed dimers, in which the triphenyltriazine acceptors are connected at the para and meta positions, respectively, while DM-G features a shorter diphenyltriazine acceptor instead. Intramolecular rotations and vibrations are expected to be suppressed efficiently by the rigid backbone, the direct attachment of the donor via the spiro centre and considerable steric constraints31. Due to the short D/A distances and nearly coplanar orientation of these units, we anticipate the formation of strongly coupled CT states and hence exciplexes with excellent emission properties. For comparison purposes, we constructed the more flexible DM-X, which differs from DM-G by a less rotationally constrained 1,2-phenylene bridge instead of the rigid fluorene linker. To analyse the effect of increasing the D/A separation, we synthesized DM-Z, in which the donor and acceptor units are positioned on opposite sides of the rigid fluorene linker. As a third reference sample, we use a 1:1 mixture of the molecular donor and acceptor components, which are 9,9-dimethyl-10-phenyl-9,10-dihydroacridine (DMTPA) and 2,4,6-triphenyl-1,3,5-triazine (TPZ), respectively.

The single-crystal X-ray structures of DM-B, DM-Bm and DM-G confirm the anticipated quasi-cofacial arrangements of the donor and acceptor subunits (Supplementary Fig. 8). The distances between the corresponding best-fit planes are as short as 3.16, 3.06 and 2.83 Å, respectively, highlighting that our SCCT design strategy enables a noticeably stronger π-orbital overlap than one would typically find in van der Waals-stacked materials, such as graphite (3.35 Å)32. The more flexible DM-X adopts a strongly distorted configuration with a D/A distance of 2.38 Å.

The ultraviolet–visible absorption spectra of DM-B, DM-Bm and DM-G exhibit an intramolecular CT transition band around 380 nm in dichloromethane (DCM) solution, indicating strong electronic couplings between the donor and acceptor moieties in their ground-state geometries (Fig. 1c). This CT absorption band is also observed for the cofacial, yet more flexible, DM-X (Supplementary Fig. 3), but is absent in the spectra of the DMTPA:TPZ mixture (Supplementary Fig. 1) and the DM-Z with its increased D/A separation (Supplementary Fig. 2). These observations confirm that the CT-state formation requires marked D/A overlap33. In accordance with its missing CT absorption feature, the fluorescence spectrum of a 1:1 DMTPA:TPZ solution in toluene is dominated by the DMTPA emission around 360 nm, with only a very weak shoulder around 487 nm, indicating the formation of an exciplex after photoexcitation (Supplementary Fig. 1). This emission feature becomes dominant in the five covalently linked D/A compounds. DM-B, DM-Bm, DM-G, DM-X and DM-Z exhibit distinct emission peaks at 476, 485, 505, 493 and 445 nm, respectively (Supplementary Figs. 13–17). The emission spectra of these compounds broaden and red-shift with increasing solvent polarity, confirming the CT character of the emission band34. Notably, DM-Z displays the most noticeable red-shift of 118 nm, from 445 nm (in toluene) to 563 nm (in DCM), owing to the largest D/A distance and hence the largest molecular dipole moment (Supplementary Fig. 13). The role of the molecular dipole moments will be discussed in more detail in the following section. In line with their shorter D/A separation, the cofacially arranged DM-B and DM-Bm exhibit reduced red-shifts of 69 and 51 nm, respectively (Supplementary Figs. 16 and 17). The even more compact diphenyltriazine-based compounds DM-G and DM-X show the smallest solvatochromic shifts of only 37 and 36 nm, respectively (Supplementary Figs. 14 and 15).

Despite their very similar absorption and emission spectra, the photoluminescence quantum efficiencies (PLQEs) of the rigid DM-G and the flexible DM-X are markedly different (51% versus 12% in toluene solution). The highest PLQEs in toluene solution are obtained for the TPZ-based DM-B and DM-Bm (78% and 69%, respectively, in toluene solution). The electronically less coupled DM-Z exhibits the lowest PLQE within this series, of only 6% in toluene solution. Embedding the emitters into a matrix of bis[2-(diphenylphosphino)phenyl]ether oxide (DPEPO) at 20 wt% concentration improves their PLQEs markedly due to the further suppression of intramolecular vibrations and rotations in the solid state32. The trend in the PLQEs, however, remains the same: DM-B (96%) > DM-Bm (92%) > DM-G (88%) > DM-X (32%) > DM-Z (23%). The PLQE of the DM-B-doped film is near unity, which is rarely achievable in D–σ–A systems or even D–π–A systems. It is noteworthy that, although their PLQEs are improved in the solid films, the flexible DM-X and DM-Z, with its increased D–A distance, cannot compete with DM-B and DM-Bm. This observation underscores the fact that control of donor and acceptor moieties in a nearly cofacial conformation is of critical importance for suppressing detrimental relaxation processes.

To estimate the energies of the lowest energy singlet (S1) and triplet (T1) excited states, we recorded the fluorescence and phosphorescence spectra in toluene at 77 K (Fig. 1c). The energy differences between these states, ΔEST, were found to be 0.17, −0.08, −0.11, 0.03 and 0.54 eV for DM-B, DM-Bm, DM-G, DM-X and DM-Z, respectively. The negative ΔEST of DM-Bm and DM-G might be due to different molecular geometries in their respective fully relaxed singlet and triplet states35 (see Supplementary Note for details). The small ΔEST values of DM-B, DM-Bm, DM-G and DM-X bode well for the application of these compounds as TADF emitters36. Detailed physical and photophysical data for all the molecules are summarized in Table 1.

Quantum-chemical calculations

To better understand the geometrical differences and photophysical properties of the D/A emitters, we performed quantum-chemical calculations using density functional theory (DFT) and time-dependent DFT (TD-DFT) methods. Ground-state and excited-state geometries were optimized at the B3LYP-D3BJ/def2-SVP and ω-tuned TD-wb97xd/ma-def2-SVP levels, respectively37,38. After excitation, donor and acceptor subunits are forced to a better cofacial geometry arrangement due to the Coulomb interaction (Supplementary Table 6). As expected, the highest occupied molecular orbitals (HOMOs) are located on the donor units, whereas the lowest unoccupied molecular orbitals (LUMOs) are concentrated on the acceptor moieties (Fig. 2a). The HOMO and LUMO energies are summarized in Supplementary Table 5. DM-B, DM-Bm, DM-G and DM-X have similar HOMO levels of −6.38, −6.32, −6.38 and −6.37 eV, respectively, whereas the DM-Z possesses a deeper HOMO level (−6.55 eV). On the other hand, DM-B, DM-Bm and DM-Z have almost identical LUMO levels of −0.71, −0.69, −0.70 eV, respectively, which are lower than those of DM-G and DM-X (−0.60 and −0.59 eV). From the calculated S1 and T1 energy levels, we estimate the ΔEST for DM-B, DM-Bm, DM-G, DM-X and DM-Z to be 0.28, 0.06, 0.05, 0.12 and 1.23 eV, respectively, which are in good agreement with the trends observed experimentally (Supplementary Table 5). In addition, the dipole moments for the S1 states of DM-B, DM-Bm, DM-G, DM-X and DM-Z are determined to be 14.7, 12.6, 10.3, 11.1 and 24.2 Debye, respectively, which are in close agreement with their solvatochromic fluorescence characteristics discussed previously.

To gain additional insight into the different roles of the fluorene spacer for the formation of the CT state, we have performed intrafragment CT analysis on the relaxed S1 states. As shown in Fig. 2b, the electron transition associated with CT-state formation in DM-B, DM-Bm, DM-G and DM-X mainly originates from the donor to the acceptor units, with minimal involvement of the fluorene spacer. However, for DM-Z, the fluorene strongly contributes to the wavefunction of the electron and hole in the CT state, which is probably a result of the weak electronic interaction between the donor and acceptor moieties. These results indicate that our SCCT molecular design strategy is beneficial for the creation of an intramolecular exciplex with pure CT character.

OLED device performance

As the SCCT-based molecules combine a very high PLQE in solid films and a sufficiently small ΔEST, we anticipated that they would be be very efficient TADF-type electroluminescent (EL) emitters. To test their potential, we fabricated OLEDs with the following structure: ITO/HAT-CN (10 nm)/TAPC (40 nm)/TCTA (8 nm)/mCP (8 nm)/DPEPO:emitters (20 nm, 5-60 wt%)/DPEPO (10 nm)/TmPyPB (40 nm)/Liq (2 nm)/Al (100 nm). Please refer to Supplementary Fig. 20 for the chemical structures and IUPAC names of the organic layers and the energy-level alignments across the devices. We also attempted to fabricate DMTPA/TPZ exciplex devices, but they degraded before measurements could be completed, illustrating the immanent phase segregation of a D/A blend that is not chemically linked39.

At a doping concentration of 20 wt%, the DM-B and DM-Z devices have a similar EL peak at around 488 nm, while the EL peak of DM-Bm, DM-G and DM-X is red-shifted to 500 nm (Supplementary Figs. 21–25). With increasing doping concentrations of DM-B from 5 wt% to 60 wt%, the corresponding Commission Internationale de l’Eclairage (CIE) coordinates of the EL emission shift from sky-blue (CIE 0.168, 0.297) to blue-green (CIE 0.210, 0.442), which may be due to intermolecular interactions between the highly polar emitter molecules at higher doping concentration.

The current density–voltage–luminance (J–V–L) characteristics of the devices based on either of the five D/A emitters show a greatly reduced driving voltage when the doping concentration of the emitter is increased (Supplementary Figs. 21–25), indicating that the charge-carrier transport through the emitters is better than through the DPEPO host material. The turn-on voltage of the device based on DM-B with a 50 wt% doping concentration is as low as 2.8 eV, and the corresponding driving voltages at 1,000 and 10,000 cd m−2 are 4.7 and 7.0 V, respectively (Fig. 3b and Supplementary Fig. 21).

OLED device characteristics of DM-B, DM-Bm, DM-G, DM-X and DM-Z. a, EL spectra with different emitters DM-B, DM-Bm, DM-G, DM-X, DM-Z and different doping ratios of DM-B. b, Current density and luminance versus driving voltage (J–V–L) characteristics. The colour legend is the same as in a. c, EQE versus luminance characteristics. The colour legend is the same as in a. d, Power eficiency versus luminance characteristics. The colour legend is the same as in a.

The device performance, however, is not compromised at these high doping levels, suggesting that the emitters are much less prone to concentration quenching than classic TADF emitters40. As shown in Fig. 3c and Supplementary Fig. 21, DM-B-based devices achieve EQEs exceeding 20% at doping concentrations ranging from 10 wt% to 60 wt%. At a doping concentration of 50 wt%, the DM-B-based device exhibits balanced hole/electron transport and broadened recombination zone in the emitting layer (Supplementary Fig. 26), resulting in a maximum EQE of 27.4% with a low efficiency roll-off of only 10.9% at 1,000 cd m−2. The maximum EQEs of the devices based on DM-Bm and DM-G are 21.7% and 18.5%, respectively, which are proportional to the PLQEs of these emitters. In stark contrast, the devices based on the more flexible and less electronically coupled DM-X and DM-Z exhibit considerably lower efficiencies (4.3% and 3.2%, respectively). The performance of the optimal devices based on DM-B, DM-Bm, DM-G, DM-X and DM-Z is summarized in Table 2.

Although the spiro-spacer has been used previously to separate D/A units in D–σ–A-type TADF molecules, devices based on those emitters exhibited relatively poor device performance41,42. For example, a classic D–σ–A-type TADF molecule, ACRFLCN (10-phenyl-10H-spiro[acridine-9,9′-fluorene]-2′,7′-dicarbonitrile), with the same spiro subunit as used in our present work, exhibited a low PLQE and a long delayed lifetime, resulting in a peak EQE of 10.1% with an efficiency roll-off of more than 90% at 100 cd m−2 (ref. 41). These findings suggest that our design strategy, namely to generate highly emissive intramolecular exciplexes via strongly coupled CT pairs with short D/A distances and a very rigid molecular configuration, can not only overcome the PLQE limitations of classical exciplexes, but also accelerate the often slow RISC rate of traditional TADF emitters.

Transient photoexcitation dynamics

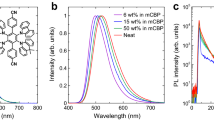

To better understand the emission mechanism, transient photoluminescence (PL) spectra were recorded for the D/A emitters in a DPEPO matrix (20 wt% doping). DM-B, DM-Bm and DM-G exhibit a prompt component with lifetimes of 91, 89 and 51 ns, and a delayed component with lifetimes of 5.0, 4.5 and 3.3 μs, respectively (Fig. 4 and Supplementary Table 9). The less favourably constructed DM-X and DM-Z show a suppressed delayed emission that is indicative of a slow and inefficient RISC process. The RISC rate (kRISC) of the efficient DM-B (kRISC = 1.8 × 105 s−1) is approximately fourfold higher than the rate observed for DM-X (kRISC = 5.0 × 104 s−1), whereas the kRISC of the other two efficient emitters, DM-Bm and DM-G, are comparable to DM-B. Intriguingly, the kRISC of DM-B is more than 30 times higher compared to the classic sky-blue TADF emitter 2CzPN (4,5-di (9H-carbazol-9-yl)phthalonitrile; ΔEST = 0.09 eV; kRISC = 5.6 × 103 s−1), despite its slightly larger ΔEST of 0.17 eV (ref. 30). Additionally, temperature-dependent time-resolved PL spectra were recorded of the 20 wt%-doped samples (Supplementary Table 10). As expected for a thermally activated process, the RISC rates become faster with increasing temperature.

a, Time-dependent transient PL decay characteristics of DM-B, DM-Bm, DM-G, DM-X and DM-Z in doped DPEPO films at room temperature. b, Time-dependent transient PL decay characteristics of DM-B in doped DPEPO film from 200 to 300 K. c, Transient absorption spectra of DM-B on nanosecond timescales in oxygen-free toluene solution. d, Normalized kinetics of DM-B on nanosecond timescales in oxygen-free toluene solution.

To gain further insight into intersystem crossing (ISC) and RISC dynamics between the relevant singlet and triplet excited states, we performed pump–probe transient absorption (TA) spectroscopy experiments for the champion material DM-B in dilute toluene solution. As depicted in Supplementary Figs. 6 and 7, the picosecond TA measurement spectra show broad photoinduced absorption (PIA) signals across the entire spectral range, overlapping with a positive stimulated emission feature at around 525 nm. Given that it is present immediately following excitation, this broad PIA peak at 670 nm is assigned to the S1 excited state. The nanosecond–microsecond TA measurements, which encompass the time range of the important ISC/RISC processes, are shown in Fig. 4c,d. Here, we can directly observe the ISC/RISC processes as the singlet PIA at 670 nm decays and a blue-shifted triplet PIA at 550 nm forms, before decaying away after 300 ns. The different PIA signals suggest a change in the orbital nature of the excited singlet and triplet states, as, if they both took a very similar CT form, we would expect the PIA transitions to higher lying states to be almost identical. This then implies that S1 is a CT excited state and T1 is a locally excited state for DM-B. This is consistent with the quantum-chemical calculations of the excited states, as discussed above.

Outlook

By employing a newly developed space-confined charge-transfer design, we have successfully resolved the long-standing challenge of comparably low efficiencies in exciplex-type light emitters. This breakthrough was enabled by locking the donor and acceptor moieties into a rigid cofacial configuration, which strengthens their ground-state electronic couplings and suppresses non-radiative decay channels. Conversely, the control experiments with more flexible molecular designs or weaker interacting subunits lead to compromised emissive properties. Our results confirm that precise control of the donor and acceptor conformation is of paramount importance for achieving a high charge-transfer emission quantum yield. Our findings should have an impact on refining our understanding of spatial coupling in charge-transfer complexes.

Several promising directions for future work can be pursued to expand the scope of the space-confined charge-transfer concept. We will explore other rigid linkers to fine tune the distances and geometries of donor and acceptor moieties. Future work will also transfer our design to other donor–acceptor combinations to tune the desired emission colour and optoelectronic properties. Following this architecture, researchers could also employ machine learning to run high-throughput virtual screening to seek more efficient emitters43. We believe that our strategy will offer an avenue for studying and utilizing through-space electronic interactions in optoelectronic materials.

Methods

Synthesis and characterization

The experimental details on the synthesis of DM-B, DM-Bm, DM-G, DM-X and DM-Z are summarized in the Supplementary Information. 1H NMR and 13C NMR were measured in CDCl3 or CD2Cl2 solutions using an Agilent DD2-600 NMR spectrometer at 298 K with chemical shifts (δ, ppm) relative to tetramethyl silane (Me4Si) for the 1H NMR and 13C NMR spectra. Mass spectroscopy was performed using a ThermoFisher ISQ Single Quadrupole GC-MS with direct probe system.

Absorption, steady-state PL spectra and PLQE measurements

Ultraviolet–visible absorption spectra were measured with a Shimadzu UV-2600 spectrophotometer. Fluorescent and phosphorescent spectra were measured using a Hitachi F-4600 spectrophotometer. Absolute PL quantum efficiencies (PLQEs) were measured on a Quantaurus-QY measurement system (C11347-11, Hamamatsu Photonics) under nitrogen flow and all samples were excited at 360 nm.

Electrochemical and thermal analysis

Electrochemical analysis was carried out using a CHI604D instrument in a conventional three-electrode configuration system: glassy carbon electrode as working electrode, Ag/AgCl electrode as reference electrode and Pt wire electrode as counter electrode. The oxidative scans were performed using 0.1 M Bu4NPF6 in DCM as the supporting electrolyte and a scan rate of 100 mV s‒1 at room temperature. Reductive scans were performed using 0.1 M Bu4NPF6 in dimethylformamide as the supporting electrolyte and a scan rate of 100 mV s‒1 at room temperature. The ferrocenium/ferrocene couple (Fc+/Fc) was used as the internal reference. Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) was performed using a Mettler Toledo TGA1 under nitrogen atmosphere. The temperature was increased to 700 °C with a heating rate of 10 °C min−1. Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) measurements were performed using a Mettler Toledo DSC1 under nitrogen atmosphere. The temperature was increased and decreased with a heating or cooling rate of 10 °C min−1. The measurements were repeated two times, and the second cycle was utilized to determine the glass transition temperature. The melting points of the compounds were measured using a BUCHI M565 melting point instrument.

Transient photoluminescence measurement

The transient PL decay characteristics of deoxygenated solution samples were recorded using a Quantaurus-Tau fluorescence lifetime measurement system (C11367-03, Hamamatsu Photonics). Time‐resolved PL of the film samples was measured using an Andor electrically gated intensified charge‐coupled device and laser excitation at 400 nm. For low-temperature measurements, an Oxford Instruments continuous flow cryostat was used with liquid helium as the coolant.

Pump–probe TA spectroscopy

Sample photoexcitation in the nanosecond TA experiments was achieved by the third harmonic (355 nm) of an electronically triggered Q-switched Nd:YVO4 laser (~1 ns pulse length, Advanced Optical Technologies, AOT-YVO-25QSPX). For the picosecond TA, ~100 fs excitation pulses at 400 nm, generated from the second harmonic of the 800 nm fundamental of the Ti:sapphire laser (Spectra Physics Solstice Ace), was used. For both temporal regions, the probe was generated by home-built broadband visible (500–770 nm) and near-infrared (830–1,025 nm) non-collinear optical parametric amplifiers, pumped by using the frequency-doubled output (400 nm) of the Ti:sapphire laser. The delay between the pump and probe pulses was varied using a Stanford DG645 delay generator for the nanosecond measurements, while a mechanical delay stage (Thorlabs, DDS300-E/M) was used to delay the probe with respect to the pump for the picosecond measurements. The transmitted probe pulses were collected with a silicon dual-line array detector (Hamamatsu, S8381-1024Q), which was driven and read out by a custom-built board from Stresing Entwicklungsbüro.

Computational methods

All DFT calculation was carried out using the Gaussian 09 E.01 software package. The gas-phase ground-state geometry optimizations were performed at B3LYP-D3BJ/def2-SVP level44. The density functional dispersion correction was conducted by Grimme’s D3 version with Becke–Johnson damping function. The TD-DFT calculation was adopted at ω-tuned TD-wb97xd/ma-def2-SVP level to optimize geometries of excited states. Then, following ref. 38, an iteration procedure was used to non-empirically tune the ω parameter. The ω-tuned, ranged, separated functional has been shown to be suitable for the description of excited states with various degrees of charge-transfer character, as shown in refs. 37,38,45. ∆EST values were calculated by the difference between the energies of the lowest excited singlet state (S1) and the lowest excited triplet state (T1) at their optimized geometries. On the basis of the results of TD-DFT calculation, hole–electron analysis was performed using the Multiwfn v.3.5.1 software package46.

OLED device fabrication and performance measurement

The glass substrates coated with indium tin oxide (ITO) layers were sequentially cleaned ultrasonically with acetone and ethanol, then dried in an oven at 110 °C for 1 h. After being treated with ultraviolet–ozone plasma, the substrates were transferred into the evaporating chamber. OLED devices were fabricated through vacuum deposition under 4 × 10−6 Torr. After the deposition of functional layers, OLED device characterization was carried out at room temperature. EL spectra, luminance and current density–voltage–luminance characteristics were measured under a constant source Keithley 2400 Source Meter and Photo Research PR 655 spectrophotometer.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request. Source data for Figs. 1c, 3 and 4 are provided with the paper. The crystallographic coordinates for the molecular structure in this study have been deposited at the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre (CCDC), under deposition numbers of 1879795 (DM-B), 1907767 (DM-Bm), 1879719 (DM-G) and 1907768 (DM-X). The crystallographic data for the materials are also available in the Supplementary Data. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Leonhardt, H. & Weller, A. Elektronenübertragungsreaktionen des angeregten Perylens. Ber. Bunsenges. Phys. Chem. 67, 791–795 (1963).

Beens, H., Knibbe, H., Weller, A., H., L. & A., W. Dipolar nature of molecular complexes formed in the excited state. J. Chem. Phys. 47, 1183–1184 (1967).

Potashnik, R., Goldschmidt, C. R., Ottolenghi, M. & Weller, A. Absorption spectra of exciplexes. J. Chem. Phys. 55, 5344–5348 (1971).

Goushi, K., Yoshida, K., Sato, K. & Adachi, C. Organic light-emitting diodes employing efficient reverse intersystem crossing for triplet-to-singlet state conversion. Nat. Photon. 6, 253–258 (2012).

Lin, T. C. et al. Probe exciplex structure of highly efficient thermally activated delayed fluorescence organic light emitting diodes. Nat. Commun. 9, 3111 (2018).

Hirata, S. et al. Highly efficient blue electroluminescence based on thermally activated delayed fluorescence. Nat. Mater. 14, 330–336 (2015).

Cui, L. S. et al. Controlling singlet–triplet energy splitting for deep-blue thermally activated delayed fluorescence emitters. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 56, 1571–1575 (2017).

Nakagawa, T., Ku, S. Y., Wong, K. T. & Adachi, C. Electroluminescence based on thermally activated delayed fluorescence generated by a spirobifluorene donor-acceptor structure. Chem. Commun. 48, 9580–9582 (2012).

Lin, T. A. et al. Sky-blue organic light emitting diode with 37% external quantum efficiency using thermally activated delayed fluorescence from spiroacridine-triazine hybrid. Adv. Mater. 28, 6976–6983 (2016).

Cui, L. S. et al. Long-lived efficient delayed fluorescence organic light-emitting diodes using n-type hosts. Nat. Commun. 8, 2250 (2017).

Liu, Y., Li, C., Ren, Z., Yan, S. & Bryce, M. R. All-organic thermally activated delayed fluorescence materials for organic light-emitting diodes. Nat. Rev. Mater. 3, 18020 (2018).

Ahn, D. H. et al. Highly efficient blue thermally activated delayed fluorescence emitters based on symmetrical and rigid oxygen-bridged boron acceptors. Nat. Photon. 13, 540–546 (2019).

Kondo, Y. et al. Narrowband deep-blue organic light-emitting diode featuring an organoboron-based emitter. Nat. Photon. 13, 678–682 (2019).

Zhang, Q. et al. Efficient blue organic light-emitting diodes employing thermally activated delayed fluorescence. Nat. Photon. 8, 326–332 (2014).

Kaji, H. et al. Purely organic electroluminescent material realizing 100% conversion from electricity to light. Nat. Commun. 6, 8476 (2015).

Uoyama, H., Goushi, K., Shizu, K., Nomura, H. & Adachi, C. Highly efficient organic light-emitting diodes from delayed fluorescence. Nature 492, 234–238 (2012).

Cui, L. S., Kim, J. U., Nomura, H., Nakanotani, H. & Adachi, C. Benzimidazobenzothiazole-based bipolar hosts to harvest nearly all of the excitons from blue delayed fluorescence and phosphorescent organic light-emitting diodes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 55, 6864–6868 (2016).

Ly, K. T. et al. Near-infrared organic light-emitting diodes with very high external quantum efficiency and radiance. Nat. Photon. 11, 63–68 (2017).

Wong, M. Y. & Zysman-Colman, E. Purely organic thermally activated delayed fluorescence materials for organic light-emitting diodes. Adv. Mater. 29, 1605444 (2017).

Cox, G. S., Turro, N. J., Yang, N. C. C. & Chen, M. J. Intramolecular exciplex emission from aqueous β-cyclodextrin solutions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 106, 422–424 (1984).

Itoh, M., Mimura, T., Usui, H. & Okamoto, T. Intramolecular exciplex and charge transfer complex formations in (9,10-dicyanoanthracene)-(trimethylene)-(naphthalene) systems. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 95, 4388–4392 (1973).

Geng, Y. et al. Donor–σ–acceptor motifs: thermally activated delayed fluorescence emitters with dual upconversion. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 56, 16536–16540 (2017).

Kawasumi, K. et al. Thermally activated delayed fluorescence materials based on homoconjugation effect of donor–acceptor triptycenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137, 11908–11911 (2015).

Tsujimoto, H. et al. Thermally activated delayed fluorescence and aggregation induced emission with through-space charge transfer. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 4894–4900 (2017).

Shi, Y. Z. et al. Intermolecular charge-transfer transition emitter showing thermally activated delayed fluorescence for efficient non-doped OLEDs. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 57, 9480–9484 (2018).

Shao, S. et al. Blue thermally activated delayed fluorescence polymers with nonconjugated backbone and through-space charge transfer effect. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 17739–17742 (2017).

Spuling, E., Sharma, N., Samuel, I. D. W., Zysman-Colman, E. & Bräse, S. (Deep) blue through-space conjugated TADF emitters based on [2.2]paracyclophanes. Chem. Commun. 54, 9278–9281 (2018).

Turro N. J., Scaiano J. C. & Ramamurthy V. Modern Molecular Photochemistry of Organic Molecules (University Science Books, 2010).

Nakanotani, H., Furukawa, T., Morimoto, K. & Adachi, C. Long-range coupling of electron–hole pairs in spatially separated organic donor-acceptor layers. Sci. Adv. 2, e1501470 (2016).

Inoue, M. et al. Effect of reverse intersystem crossing rate to suppress efficiency roll-off in organic light-emitting diodes with thermally activated delayed fluorescence emitters. Chem. Phys. Lett. 644, 62–67 (2016).

Sicard, L. J. et al. C1-linked spirobifluorene dimers: pure hydrocarbon hosts for high-performance blue phosphorescent oleds. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 58, 3848–3853 (2019).

Benedict, L. X. et al. Microscopic determination of the interlayer binding energy in graphite. Chem. Phys. Lett. 286, 490–496 (1998).

Kulkarni, A. P. & Jenekhe, S. A. Blue-green, orange, and white organic light-emitting diodes based on exciplex electroluminescence of an oligoquinoline acceptor and different hole-transport materials. J. Phys. Chem. C. 112, 5174–5184 (2008).

Reichardt, C. Solvatochromic dyes as solvent polarity indicators. Chem. Rev. 94, 2319–2358 (1994).

Hussain, A., Yuan, H., Li, W. & Zhang, J. Theoretical investigations of the realization of sky-blue to blue TADF materials via CH/N and H/CN substitution at the diphenylsulphone acceptor. J. Mater. Chem. C. 7, 6685–6691 (2019).

Yersin, H et al. Highly Efficient OLEDs: Materials Based on Thermally Activated Delayed Fluorescence (Wiley, 2019).

Sun, H., Zhong, C. & Brédas, J. L. Reliable prediction with tuned range-separated functionals of the singlet–triplet gap in organic emitters for thermally activated delayed fluorescence. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 11, 3851–3858 (2015).

Sun, H. et al. Impact of dielectric constant on the singlet–triplet gap in thermally activated delayed fluorescence materials. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 8, 2393–2398 (2017).

Bertho, S. et al. Improved thermal stability of bulk heterojunctions based on side-chain functionalized poly(3-alkylthiophene) copolymers and PCBM. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 110, 69–76 (2013).

Kim, H. S., Park, S. R. & Suh, M. C. Concentration quenching behavior of thermally activated delayed fluorescence in a solid film. J. Phys. Chem. C. 121, 13986–13997 (2017).

Nasu, K. et al. A highly luminescent spiro-anthracenone-based organic light-emitting diode exhibiting thermally activated delayed fluorescence. Chem. Commun. 49, 10385–10387 (2013).

Méhes, G., Nomura, H., Zhang, Q., Nakagawa, T. & Adachi, C. Enhanced electroluminescence efficiency in a spiro-acridine derivative through thermally activated delayed fluorescence. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 51, 11311–11315 (2012).

Gómez-Bombarelli, R. et al. Design of efficient molecular organic light-emitting diodes by a high-throughput virtual screening and experimental approach. Nat. Mater. 15, 1120–1127 (2016).

Grimme, S., Ehrlich, S. & Goerigk, L. Effect of the damping function in dispersion corrected density functional theory. J. Comput. Chem. 32, 1456–1465 (2011).

Sun, H. & Autschbach, J. Electronic energy gaps for π-conjugated oligomers and polymers calculated with density functional theory. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 10, 1035–1047 (2014).

Lu, T. & Chen, F. Multiwfn: a multifunctional wavefunction analyzer. J. Comput. Chem. 33, 580–592 (2012).

Acknowledgements

X.T., H.-C.L., Y.-K.Q., Z.-Q.J. and L.-S.L acknowledge financial support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant nos. 51773141, 61961160731 and 51873139), the National Key R&D Programme of China (no. 2016YFB0400700). L.-S.C., A.J.G. and R.H.F. acknowledge the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (EPSRC) for funding (EP/M01083X/1 and EP/M005143/1). F.A. acknowledges financial support from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (grant agreement no. 670405). This project is also funded by the Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province of China (BK20181442), Collaborative Innovation Centre of Suzhou Nano Science & Technology, the Priority Academic Programme Development of Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions (PAPD) and the ‘111’ Project.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The project was conceived and designed by L.-S.C. and Z.-Q.J. X.T. carried out the device characterizations under the supervision of L.-S.L. H.-C.L. synthesized the compounds under the supervision of Z.-Q.J. A.J.G. conducted the transient absorption experiments and analysed the results. F.A. participated in the discussion and edited the manuscript. Y.-K.Q. conducted the crystal structure measurements and analysed the results. C.Z. performed the computational experiments. S.T.E.J. assisted with the temperature-dependent transient photoluminescence measurements. L.-S.L. and R.H.F. supervised the work. X.T., L.-S.C. and Z.-Q.J. analysed all data and wrote the manuscript. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figs. 1–33, note and Tables 1–10.

Supplementary Data 1

Crystallographic data of DM-B.

Supplementary Data 2

Crystallographic data of DM-Bm.

Supplementary Data 3

Crystallographic data of DM-G.

Supplementary Data 4

Crystallographic data of DM-X.

Source data

Source Data Fig. 1

Absorption, photoluminescence and phosphorescence data to generate Fig. 1c.

Source Data Fig. 3

Device performance data to generate Fig. 3.

Source Data Fig. 4

Transient PL and transient absorption data to generate Fig. 4.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Tang, X., Cui, LS., Li, HC. et al. Highly efficient luminescence from space-confined charge-transfer emitters. Nat. Mater. 19, 1332–1338 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41563-020-0710-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41563-020-0710-z

This article is cited by

-

Molecular engineering of LRCT-SRCT interplay enables high-performance, high color purity deep-blue OLEDs

Science China Chemistry (2026)

-

Strategic dihedral angle engineering for high-efficiency through-space charge transfer TADF emitters

Science China Materials (2026)

-

Stable narrowband blue OLEDs by modulating frontier molecular orbital levels

Nature Communications (2025)

-

Emergent clusteroluminescence from nonemissive molecules

Nature Communications (2025)

-

Ultra-low power-consumption OLEDs via phosphor-assisted thermally-activated-delayed-fluorescence-sensitized narrowband emission

Nature Communications (2025)