Abstract

Wave interference allows unprecedented coherent control of various physical properties and has been widely studied in electronic and photonic materials. However, the interference of phonons, or thermal vibrations, central to understanding coherent thermal transport in all electrically insulating materials, has been poorly characterized due to experimental challenges. Here we report the observation of phonon interference at room temperature in molecular-scale junctions. This is enabled by custom-developed scanning thermal probes with combined high stability and sensitivity, allowing quantification of heat flow through molecular junctions one molecule at a time. Using isomers of oligo(phenylene ethynylene)3 with either para- or meta-connected centre rings, our experiments revealed a remarkable reduction in thermal conductance in meta-conformations. Quantum-mechanically accurate molecular dynamics simulations show that this difference arises from the destructive interference of phonons through the molecular backbone. This work opens opportunities for studying numerous wave-driven material properties of phonons down to the single-molecule level that have remained experimentally inaccessible.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$32.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $21.58 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

The data supporting this study’s findings are available via figshare at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.28462397 (ref. 61).

Code availability

The code used to analyse the data in this study is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Chen, G. Non-Fourier phonon heat conduction at the microscale and nanoscale. Nat. Rev. Phys. 3, 555–569 (2021).

Maldovan, M. Phonon wave interference and thermal bandgap materials. Nat. Mater. 14, 667–674 (2015).

Waldrop, M. M. The chips are down for Moore’s law. Nature 530, 144–147 (2016).

Nomura, M. et al. Review of thermal transport in phononic crystals. Mater. Today Phys. 22, 100613 (2022).

Tavakoli, A. et al. Heat conduction measurements in ballistic 1D phonon waveguides indicate breakdown of the thermal conductance quantization. Nat. Commun. 9, 4287 (2018).

Luckyanova, M. N. et al. Coherent phonon heat conduction in superlattices. Science 338, 936–939 (2012).

Ravichandran, J. et al. Crossover from incoherent to coherent phonon scattering in epitaxial oxide superlattices. Nat. Mater. 13, 168–172 (2013).

Sivan, A. K. et al. GaAs/GaP superlattice nanowires for tailoring phononic properties at the nanoscale: implications for thermal engineering. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 6, 18602–18613 (2023).

Zen, N. et al. Engineering thermal conductance using a two-dimensional phononic crystal. Nat. Commun. 5, 3435 (2014).

Maire, J. et al. Heat conduction tuning by wave nature of phonons. Sci. Adv. 3, e1700027 (2017).

Lee, J. et al. Investigation of phonon coherence and backscattering using silicon nanomeshes. Nat. Commun. 8, 1–8 (2017).

Alaie, S. et al. Thermal transport in phononic crystals and the observation of coherent phonon scattering at room temperature. Nat. Commun. 6, 7228 (2015).

Aradhya, S. V. & Venkataraman, L. Single-molecule junctions beyond electronic transport. Nat. Nanotechnol. 8, 399–410 (2013).

Dubi, Y. & Di Ventra, M. Colloquium: heat flow and thermoelectricity in atomic and molecular junctions. Rev. Mod. Phys. 83, 131–155 (2011).

Cui, L., Miao, R., Jiang, C., Meyhofer, E. & Reddy, P. Perspective: thermal and thermoelectric transport in molecular junctions. J. Chem. Phys. 146, 092201 (2017).

Gotsmann, B., Gemma, A. & Segal, D. Quantum phonon transport through channels and molecules—a perspective. App. Phys. Lett. 120, 160503 (2022).

Markussen, T. Phonon interference effects in molecular junctions. J. Chem. Phys. 139, 244101 (2013).

Klöckner, J. C., Cuevas, J. C. & Pauly, F. Tuning the thermal conductance of molecular junctions with interference effects. Phys. Rev. B 96, 245419 (2017).

Chen, R., Sharony, I. & Nitzan, A. Local atomic heat currents and classical interference in single-molecule heat conduction. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 11, 4261–4268 (2020).

Sadeghi, H. Quantum and phonon interference-enhanced molecular-scale thermoelectricity. J. Phys. Chem. C 123, 12556–12562 (2019).

Henry, A. & Chen, G. High thermal conductivity of single polyethylene chains using molecular dynamics simulations. Phys. Rev. Lett. 101, 235502 (2008).

Ren, J., Hänggi, P. & Li, B. Berry-phase-induced heat pumping and its impact on the fluctuation theorem. Phys. Rev. Lett. 104, 170601 (2010).

Zhan, F., Li, N., Kohler, S. & Hänggi, P. Molecular wires acting as quantum heat ratchets. Phys. Rev. E 80, 061115 (2009).

Menezes, M. G., Saraiva-Souza, A., Del Nero, J. & Capaz, R. B. Proposal for a single-molecule field-effect transistor for phonons. Phys. Rev. B 81, 012302 (2010).

Díaz, E., Gutierrez, R. & Cuniberti, G. Heat transport and thermal rectification in molecular junctions: a minimal model approach. Phys. Rev. B 84, 144302 (2011).

Segal, D. & Nitzan, A. Heat rectification in molecular junctions. J. Chem. Phys. 122, 194704 (2005).

Bourgeois, O., André, E., Macovei, C. & Chaussy, J. Liquid nitrogen to room-temperature thermometry using niobium nitride thin films. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 77, 126108 (2006).

Dechaumphai, E. & Chen, R. Sub-picowatt resolution calorimetry with niobium nitride thin-film thermometer. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 85, 094903 (2014).

Cui, L. et al. Thermal conductance of single-molecule junctions. Nature 572, 628–633 (2019).

Mosso, N. et al. Thermal transport through single-molecule junctions. Nano Lett. 19, 7614–7622 (2019).

Guédon, C. M. et al. Observation of quantum interference in molecular charge transport. Nat. Nanotechnol. 7, 305–309 (2012).

Vazquez, H. et al. Probing the conductance superposition law in single-molecule circuits with parallel paths. Nat. Nanotechnol. 7, 663–667 (2012).

Chen, Z. et al. Quantum interference enhances the performance of single-molecule transistors. Nat. Nanotechnol. 19, 1–7 (2024).

Li, Y. et al. Gate controlling of quantum interference and direct observation of anti-resonances in single molecule charge transport. Nat. Mater. 18, 357–363 (2019).

Frisenda, R., Janssen, V. A. E. C., Grozema, F. C., van der Zant, H. S. J. & Renaud, N. Mechanically controlled quantum interference in individual π-stacked dimers. Nat. Chem. 8, 1099–1104 (2016).

Miao, R. et al. Influence of quantum interference on the thermoelectric properties of molecular junctions. Nano Lett. 18, 5666–5672 (2018).

Bai, J. et al. Anti-resonance features of destructive quantum interference in single-molecule thiophene junctions achieved by electrochemical gating. Nat. Mater. 18, 364–369 (2019).

Garner, M. H. et al. Comprehensive suppression of single-molecule conductance using destructive σ-interference. Nature 558, 416–419 (2018).

Lee, W. et al. Heat dissipation in atomic-scale junctions. Nature 498, 209–212 (2013).

Luo, T. & Chen, G. Nanoscale heat transfer—from computation to experiment. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 15, 3389–3412 (2013).

Cuevas, J. C. & Scheer, E. Molecular Electronics: An Introduction to Theory and Experiment (World Scientific, 2017).

Segal, D. & Agarwalla, B. K. Vibrational heat transport in molecular junctions. Ann. Rev. Phys. Chem. 67, 185–209 (2016).

Cacelli, I. & Prampolini, G. Parametrization and validation of intramolecular force fields derived from DFT calculations. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 3, 1803–1817 (2007).

Sääskilahti, K., Oksanen, J., Tulkki, J. & Volz, S. Role of anharmonic phonon scattering in the spectrally decomposed thermal conductance at planar interfaces. Phys. Rev. B 90, 134312 (2014).

Ruffieux, P. et al. On-surface synthesis of graphene nanoribbons with zigzag edge topology. Nature 531, 489–492 (2016).

Yelishala, S. C., Murphy, C. & Cui, L. Molecular perspective and engineering for thermal transport and thermoelectricity in polymers. J. Mat. Chem. A 12, 10614–10658 (2024).

Cui, L. et al. Quantized thermal transport in single-atom junctions. Science 355, 1192–1195 (2017).

Cui, L. et al. Study of radiative heat transfer in ångström- and nanometer-sized gaps. Nat. Commun. 8, 14479 (2017).

Reid, M. T. H. & Johnson, S. G. Efficient computation of power, force, and torque in BEM scattering calculations. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propag. 63, 3588–3598 (2015).

Gemma, A. et al. Full thermoelectric characterization of a single molecule. Nat. Commun. 14, 1–6 (2023).

Thompson, A. P. et al. LAMMPS—a flexible simulation tool for particle-based materials modeling at the atomic, meso, and continuum scales. Comput. Phys. Commun. 271, 108171 (2022).

Tuckerman, M., Berne, B. J. & Martyna, G. J. Reversible multiple time scale molecular dynamics. J. Chem. Phys. 97, 1990–2001 (1992).

Grønbech-Jensen, N. Complete set of stochastic Verlet-type thermostats for correct Langevin simulations. Mol. Phys. 118, 1662506 (2020).

Schneider, T. & Stoll, E. Molecular-dynamics study of a three-dimensional one-component model for distortive phase transitions. Phys. Rev. B 17, 1302 (1978).

Berendsen, H. J. C., Postma, J. P. M., Van Gunsteren, W. F., Dinola, A. & Haak, J. R. Molecular dynamics with coupling to an external bath. J. Chem. Phys. 81, 3684–3690 (1984).

Sheng, H. W., Kramer, M. J., Cadien, A., Fujita, T. & Chen, M. W. Highly optimized embedded-atom-method potentials for fourteen FCC metals. Phys. Rev. B 83, 134118 (2011).

Mahaffy, R., Bhatia, R. & Garrison, B. J. Diffusion of a butanethiolate molecule on a Au{111} surface. J. Phys. Chem. B 101, 771–773 (1997).

Heinz, H., Lin, T. J., Kishore Mishra, R. & Emami, F. S. Thermodynamically consistent force fields for the assembly of inorganic, organic, and biological nanostructures: the INTERFACE force field. Langmuir 29, 1754–1765 (2013).

Ventura‐Macias et al. Quantum mechanical derived (VdW‐DFT) transferable Lennard–Jones and Morse potentials to model cysteine and alkanethiol adsorption on Au (111). Adv. Mater. Inter. 11, 2400369 (2024).

Fan, Z. et al. Force and heat current formulas for many-body potentials in molecular dynamics simulations with applications to thermal conductivity calculations. Phys. Rev. B 92, 094301 (2015).

Yelishala, S. C. et al. Phonon interference in single-molecule junctions. figshare https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.28462397 (2025).

Acknowledgements

L.C. acknowledges support from the National Science Foundation (award number 2239004) and the College of Engineering and Applied Science at University of Colorado Boulder. We thank S. Bilan for technical support. P.M.M. acknowledges support from the Spanish Ministry of Education and Professional Formation (award number FPU21/06224). J.C.C. thanks the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation (award number PID2020-114880GB- I00) and the ‘Maria de Maeztu’ Programme for Units of Excellence in R&D (award number CEX2023-001316-M). J.G.V. acknowledges the Spanish CM ‘Talento Program’ (award number 2020-T1/ND-20306) and the Spanish Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovacion (award numbers PID2020-113722RJ-I00, TED2021-132219A-I00 and CNS2023-144011). This work utilized research computing resources at Picasso, Finisterrae3 (award numbers RES-FI-2023-0031 and RES-FI-2023-2-0006) and at the University of Colorado Boulder Research Computing, which is supported by the NSF (award numbers ACI-1532235 and ACI-1532236), the University of Colorado Boulder and Colorado State University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The project was conceived by L.C. The experiments were performed by S.C.Y. The twin-tip scanning thermal probes were fabricated by Y.Z. The MD simulations were performed by P.M.M., and the QM-FF was developed by G.P. The molecules were synthesized by H.C. under the supervision of W.Z. The near-field thermal simulations were performed by M.H. The manuscript was prepared by S.C.Y., P.M.M., J.C.C., J.G.V. and L.C., with comments and inputs from all authors.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Materials thanks Abraham Nitzan and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Extended Data Fig. 1 Nanofabrication steps of the twin-tip SThM probe.

Step 1) NbN lines on two probe beams are defined and sputtered on the oxide surface. Steps 2 and 3) Cr/Au metallization layer and tunnelling current path are deposited via e-beam evaporation. Step 4) The shape of the probe beams is defined and formed using deep reactive ion etching. Step 5) The whole probe is released from the Si wafer. Step 6) Individual probes are aligned on a shadow mask. Step 7) The probe is fixed on the shadow mask. Step 8) A thin layer of gold film (100 nm) is deposited on the tip of the scanning probe. Step 9) The probe is detached from the shadow mask, cleaned, and installed into the UHV SPM chamber for measurements.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Thermal characterization of the SThM probe.

a, Temperature coefficient of resistance (TCR) and electrical resistance of NbN resistive thermometer as a function of temperature. b, The heating power required to increase the probe by a given temperature is plotted to obtain the thermal conductance of the probe. c, The normalized temperature increase on the probe as a function of heating frequency, where the thermal cut-off frequency (-3 dB point) is 14 Hz.

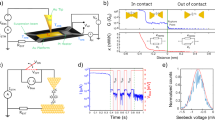

Extended Data Fig. 3 Thermal signal characterization.

a, Data recordings for different measurement schemes showing twin-tip scheme with peak-to-peak fluctuations of ± 3.5 µV, single-tip (that is, without matching probe) scheme with fluctuations of ± 15 µV, and no tip (that is, two precision resistors replacing the scanning thermal probes) scheme with equivalent fluctuations of ± 0.15 µV. b, Power Spectral Density (PSD) analysis for different schemes. The inset shows a logarithmic plot to elucidate the difference between each scheme. The shaded region indicates the reduced thermal drift when applying the twin-probe scheme as opposed to a single-tip scheme.

Extended Data Fig. 4 Measured electrical conductance histograms of three molecular junctions.

The black lines in (a-c) show the Gaussian peak of the histograms, providing the most probable conductance values of the junctions. These electrical conductance values are used to guide the thermal measurements to indicate the formation of a single-molecule junction.

Extended Data Fig. 5 Sample full approach-withdraw thermal and electrical conductance traces and evaluation of thermal background signal in the measurement of single-molecule junctions.

a, b, Two independent recordings of thermal and electrical traces during the approach, stop, and withdrawal of the scanning thermal probe on a para-OPE3 molecule sample. Before the formation of the single-molecule junction, the approach speed of the tip is at 200 pm s–1, and the withdraw speed is at 50 pm s–1. After the junction ruptures, a 10-nm piezo withdraw is applied at 3 nm s–1 (pink shaded region) to evaluate the background level of the thermal signal, which is observed to be ~100 pW K-1 and can be largely attributed to the near-field radiative heat transfer between the tip and the sample. c, Calculated near-field radiative heat transfer between a hot Au tip and Au substrate as a function of distance using SCUFF-EM. The shaded region is the error band and is ± one standard deviation from 25 different profiles of roughness. d, Thermal background signal of this study compared to previous single-molecule thermal measurements.

Extended Data Fig. 6 Geometry and interface potential independence of the lower thermal conductivity of meta-OPE3 compared to para-OPE3.

Cumulative integral of the thermal conductance \({{\rm{G}}}_{{\rm{th}}}^{{\rm{c}}}({\rm{\omega }})\) for various contact geometries for meta- (in pink) and para-OPE3 molecules (in red). Dashed lines show the total conductance values according to the energy exchange with the thermostats. The data corresponds to single production runs. The yellow shaded region represents the allowed frequencies inside the contacts, that is, the Debye frequency of gold ( ~ 161 cm–1). Each column corresponds to a different stable contact geometry. Left: pristine surfaces. Middle: molecule tethered in an Au terrace. Right: hollow-hollow contacts (fcc sites). Each row corresponds to a different Au-S interaction potential. Top row: Morse potential from ref. 57. Bottom row: Morse potential (PTH) from ref. 59. Histograms on the right margin correspond to the results shown in Fig. 3e to facilitate comparison with experiments.

Extended Data Fig. 7 Elastic thermal transport in single OPE3 junctions.

a, Spectral heat current q(ω) across meta-OPE3 evaluated at two different atomic planes within the same NEMD trajectory. Note that due to thermal noise, the signal fluctuates around 0 beyond 180 cm–1, although this has no impact on the total integral, as shown in the main text. The yellow shaded region represents the allowed frequencies inside the gold contacts, that is, gold Debye frequency ( ~ 161 cm–1). b, Contact geometry showing the different planes at which the spectral heat current shown in (a) are computed. The colour of each plane matches the plot. The position independence of the spectral heat current implies that the phonon transport in these junctions is essentially elastic. This justifies our theory analysis of the impact of phonon interferences in terms of the phonon transmission function and the corresponding transmission kernel.

Extended Data Fig. 8 Influence of thermal fluctuations on the transmission kernel (|dlr(ω)|2).

a, c, Distance between the last two layers of the Au tips during a NEMD trajectory for the meta-OPE3 (a) and para-OPE3 (c) junctions. Dashed lines highlight the selected distances for the calculation of the transmission kernel. b, d, Transmission kernel |dlr(ω)|2 for meta-OPE3 (b) and para-OPE3 (d) junctions locating both Au atoms at the distances shown in (a-c). Data shown in Fig. 4e was computed for gap sizes within one standard deviation for meta- and para-OPE3. In panel (b), arrows point at new destructive interference emerging at compressed conformations of the meta-OPE3 molecular contact. They appear in a frequency range (shaded region) void of normal modes both in the equilibrium state and in all configurations sampled from the dynamics. Note that such interferences are exclusively a dynamic effect, that is they would not appear in static-equilibrium calculations. Another remarkable feature of this dynamic destructive interference is that it results from a combination of several vibration modes building up systematically inside the aforementioned gap. This differs from the ‘two-mode’ destructive interference picture often used to describe this phenomenon.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Notes 1–10, Supplementary Figures 1–9 and Supplementary Tables 1–9.

Supplementary Video 1

All-atom NEMD trajectory sampled every 25 ps for 30 ns imposing a steady heat flux through the meta-OPE3 molecular junction from the hot reservoir (left at 330 K) towards the cold (right at 290 K). The hollow tip geometry prevents the molecule from diffusing and reduces the overall thermal conductance. Note how the thermal fluctuations experienced by the atoms in the junction, which are fully accounted for in the spectral heat flux q(ω) shown in Fig. 4c, largely deviate from small near-equilibrium oscillations assumed in static-DFT framework within the harmonic approximation.

Supplementary Video 2

All-atom NEMD trajectory sampled every 25 ps for 30 ns imposing a steady heat flux through the para-OPE3 molecular junction from the hot reservoir (left at 330 K) towards the cold (right at 290 K). The hollow tip geometry prevents the molecule from diffusing and reduces the overall thermal conductance. Note how the thermal fluctuations experienced by the atoms in the junction, which are fully accounted for in the spectral heat flux q(ω) shown in Fig. 4c, largely deviate from small near-equilibrium oscillations assumed in static-DFT framework within the harmonic approximation.

Supplementary Video 3

All-atom NEMD trajectory sampled every 25 ps for 30 ns imposing a steady heat flux through the meta-OPE3 molecular junction from the hot reservoir (left at 330 K) towards the cold (right at 290 K). The pristine gold surface allows for molecular diffusion across the gap between the reservoirs. Note how the thermal fluctuations experienced by the atoms in the junction, which are fully accounted for in the spectral heat flux q(ω) shown in Fig. 4c, largely deviate from small near-equilibrium oscillations assumed in static-DFT framework within the harmonic approximation.

Supplementary Video 4

All-atom NEMD trajectory sampled every 25 ps for 30 ns imposing a steady heat flux through the para-OPE3 molecular junction from the hot reservoir (left at 330 K) towards the cold (right at 290 K). The pristine gold surface allows for molecular diffusion across the gap between the reservoirs. Note how the thermal fluctuations experienced by the atoms in the junction, which are fully accounted for in the spectral heat flux q(ω) shown in Fig. 4c, largely deviate from small near-equilibrium oscillations assumed in static-DFT framework within the harmonic approximation.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Yelishala, S.C., Zhu, Y., Martinez, P.M. et al. Phonon interference in single-molecule junctions. Nat. Mater. 24, 1258–1264 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41563-025-02195-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41563-025-02195-w

This article is cited by

-

Detecting interference of lattice vibrations

Nature Materials (2025)