Abstract

The confinement of electromagnetic radiation to subwavelength scales relies on strong light–matter interactions. In the infrared and terahertz spectral ranges, phonon polaritons are commonly employed to achieve deeply subdiffractional light confinement, with such optical modes offering much lower losses in comparison to plasmon polaritons. Among these, hyperbolic phonon polaritons in anisotropic materials offer a promising platform for light confinement. Here we report on ultraconfined phonon polaritons in hafnium-based dichalcogenides with confinement factors exceeding λ0/250 in the terahertz spectral range. This extreme light compression within deeply subwavelength thin films is enabled by the large magnitude of the light–matter coupling strength in these compounds and the natural hyperbolicity of HfSe2. Our findings emphasize the role of light–matter coupling for polariton confinement, which for phonon polaritons in polar dielectrics is dictated by the transverse–longitudinal optical phonon energy splitting. Our results demonstrate transition-metal dichalcogenides as an enabling platform for terahertz nanophotonic applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

A prominent focus of the field of nanophotonics is the ability to confine electromagnetic energy to highly subdiffractional length scales. This enables increased electric field intensities that can enhance light–matter interactions. Remarkable light compression has been achieved by reducing the light–matter interaction volume using resonant cavities and atomic-layer thicknesses of materials1,2. Nonetheless, this increased optical confinement is severely hampered in many cases owing to high losses. Polaritons, hybrid light–matter quasiparticles, have facilitated extreme light confinement3,4,5,6, thus enabling subdiffractional imaging7,8, nanoscale spectroscopy9 and nanophotonic circuits10. Strong optical responses from exciton polaritons occur at visible and near-infrared wavelengths, whereas extremely confined plasmon polaritons in atomically thin graphene form at longer wavelengths6. At mid-infrared (mid-IR) wavelengths, optically active polar lattice vibrations couple with light to create phonon polaritons (PhPs) that can propagate with high momenta k (refs. 11,12), spectral tunability13 and propagation directionality14 with the advantage of substantially reduced losses with respect to plasmon polaritons in conductors11,12.

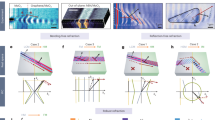

Surface PhPs can occur within the Reststrahlen band (RB) of polar dielectric materials, which is defined as the frequency range between the transverse optical (TO) and longitudinal optical (LO) phonons, within which the real part of the dielectric permittivity tensor is negative (ε < 0)11,12. The modes comprise evanescent waves bound to the surface of the polaritonic medium with subdiffractional polariton wavelengths λp. Moving from bulk to thin films, the surface-bound waves hybridize and confine further (~λ0/30, where λ0 is the free-space wavelength)15,16 as the thickness decreases (proportional to 1/d, where d is the thickness)17,18. In the same vein, efforts to achieve maximum confinement (λ0/λp) have been focused on using atomically thin films1,18 or identifying anisotropic materials that exhibit an extreme form of birefringence called hyperbolicity18,19,20, which occurs in materials with dielectric permittivities of opposite sign along different crystallographic directions. In hexagonal crystals, such as hexagonal boron nitride (hBN), hyperbolicity is realized along in- and out-of-plane crystallographic directions resulting in ε∥ε⊥ < 0. Hyperbolicity is commonly found in van der Waals (vdW) crystals, which comprise covalently bonded two-dimensional (2D) sheets along the tangential plane (x–y, labelled as t) that are stacked axially (z) and held together by weaker vdW bonds3,4,5,8. Phonons in uniaxial vdW crystals with polarizations oriented in the tangential and axial directions are, therefore, not degenerate and induce a natural anisotropy resulting in non-identical permittivities (εt ≠ εz). The large confinement occurs owing to the extraordinary modes, namely hyperbolic PhPs that have nominally unrestricted magnitudes of k that traverse through the volume of the material18. Furthermore, in ultrathin hyperbolic films, where the thickness is far below the free-space wavelength (d « λ0), the PhP confinement scales as 1/d down to the monolayer limit18. Despite reports of exceptionally high confinement (λ0/500)1, the losses encountered at these atomic scales far outweigh the intensity required for a PhP to propagate sufficiently for many applications. At more modest film thicknesses (d = 10–100 nm), PhP propagation is achievable but not without sacrificing confinement to values of approximately λ0/100 (refs. 18,20). Similar confinement levels have also been achieved with an alternative approach of placing a thin high-index superstrate on an isotropic medium that supports PhPs16,21.

PhP materials with high confinement, such as alpha-phase molybdenum trioxide (α-MoO3)14,20,22 and hBN5,18, have large LO–TO phonon splitting (>100 cm−1)18,23. Broad RBs play an important role in confinement, as the large bandwidth allows the PhP to extend to high k before dissipating while maintaining a non-zero group velocity (vg = dω/dk). Furthermore, the magnitude of the light–matter coupling strength is directly related to the LO–TO phonon energy splitting, which is a function of the Born effective charge11. However, this is also an absolute quantity that tends to be larger for mid-IR phonons compared with those resonant within the terahertz range. A polar dielectric material with a similar RB width as hBN at terahertz frequencies would, therefore, exhibit drastically increased light–matter coupling strengths and stronger optical confinement than other terahertz resonant materials19,24,25,26. Exceptionally large Born effective charges of hafnium-based dichalcogenides (HfDCs) give rise to their large LO–TO energy splittings27,28, whereas the heavy Hf-ion mass places their natural optical phonon frequencies in the terahertz range. The natural anisotropy of these 2D vdW crystals, accompanied with their strong light–matter coupling strength, highlights them as excellent candidates for exploring ultraconfined PhPs in the terahertz spectral regime27.

In this work, we observe ultrahigh confinement of terahertz light within two HfDCs, hafnium disulfide (HfS2) and hafnium diselenide (HfSe2), with PhP wavelengths λp that are strongly compressed with respect to the free-space values (λ0/λp > 250). We examine the terahertz near-field response of this unique set of materials using a scattering-type scanning near-field optical microscope (s-SNOM), with the light provided by a free-electron laser (FEL). Although they have the same hexagonal crystal structure, HfS2 and HfSe2 have different infrared dielectric permittivities27 that separate the predominant types of PhPs that can be supported into elliptic and hyperbolic, respectively. In this regard, elliptic refers to an anisotropic response whereby the in- and out-of-plane dielectric permittivities are different in magnitude but are both negative in sign, whereas for hyperbolicity, one of these directions is negative while the other is positive5. Interestingly, we observe very strong confinement of PhPs in ultrathin films of both materials for extremely small film thicknesses d compared with the long terahertz wavelengths (λ0/d ≈ 103). This is possible because the LO–TO splittings of HfS2 and HfSe2 are on par with high-confinement mid-IR PhP materials. However, when normalized by the resonant frequency ωTO, the HfDCs display much larger light–matter coupling strengths, which are responsible for the observed ultrahigh-k PhPs. Furthermore, we demonstrate terahertz hyperlensing by placing a metal nano-antenna below a hyperbolic HfSe2 flake, which enables the observation of hyperbolic rays that can be used for deeply subdiffractional terahertz imaging. The observation of ultraconfined terahertz polaritons in Hf-based vdW crystals therefore demonstrates high promise for deeply subdiffractional terahertz nanophotonic components.

Ultraconfined thin-film polaritons

Directly observing highly confined PhPs in the far field might be challenging owing to the intrinsic momentum mismatch with free-space light, which is orders of magnitude when comparing the terahertz range with the nanoscale polariton wavelengths supported. Near-field microscopy using s-SNOM is ideally suited to access and directly image highly confined PhP modes29,30,31. Notably, the accessible momentum range in this work is experimentally limited, rather than limited by the material response, yet still the nanotip size used for s-SNOM provides access to even larger confinement factors in the terahertz than is possible in the mid-IR. We use a tunable FEL to generate narrowband terahertz radiation32,33,34, which when scattered off the s-SNOM tip or the edges of the HfDC flakes results in scattered fields with momenta sufficient to launch and detect highly confined PhP modes. An image of the PhP field propagation was obtained by rastering the tip across the surface of the flake and collecting the scattered light at each point. Schematics of the s-SNOM apparatus and of PhPs launching from the edge of a flake are provided in Fig. 1a.

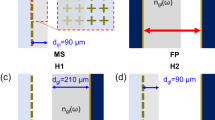

a, Schematic of the experimental s-SNOM apparatus. A tunable FEL generates narrowband terahertz radiation, which is focused onto the s-SNOM tip and is backscattered into a photoconducting detector. Inset: terahertz light scatters off the edge of a HfDC flake, launching PhPs, which are then coupled out to free space by the s-SNOM tip. The layered crystal structure of vdW-bonded HfSe2 is also shown. b, Line profiles, normalized by the free-space wavelength λ0, of the raw s-SNOM amplitude (SO2A, offset for clarity) show the propagation of edge-launched PhPs (with the edge to the left) for three samples: HfSe2 on Si (d = 47 nm, λ0 = 61.7 µm, blue circles), HfSe2 on SiO2 (d = 68 nm, λ0 = 60.7 µm, dark blue circles) and HfS2 on SiO2 (d = 68 nm, λ0 = 41.7 µm, dark blue diamonds). Each profile was fitted (Supplementary Information, section 2) to extract the polariton wavelengths λp, which are labelled along with the corresponding confinement factors. Exp., experimental data.

One-dimensional line profiles are extracted from the s-SNOM images (Supplementary Information, section 1) perpendicular to the edge of the flakes and plotted in Fig. 1b for three sample configurations: HfS2 on a SiO2 substrate (dark blue diamonds), HfSe2/SiO2 (dark blue circles) and HfSe2/Si (blue circles). Each line profile is normalized on the x axis by λ0. Fits of the line profiles show that edge-launched polaritons dominate the response. These are then scattered to the far field by the s-SNOM tip (Supplementary Information, section 2). The peak-to-peak distance between fringes, therefore, corresponds to the polariton wavelength23,35. Deeply subdiffractional modes are observed in HfS2/SiO2 (λp = 600 nm, λ0 = 41.7 μm and d = 68 nm) and HfSe2/SiO2 (λp = 645 nm, λ0 = 60.7 μm and d = 68 nm). The PhP confinement factors (λ0/λp) are 70 and 95, respectively, as shown in Fig. 1b. Notably, we observe an even larger confinement of >250 for HfSe2/Si with a polariton wavelength of 245 nm (λ0 = 61.7 μm and d = 47 nm, blue curve in Fig. 1b). Such extreme PhP confinement, without enhancement from nano-resonators, has previously been reported only for mono- and few-layer materials with high propagation losses1. However, the thicknesses d of the HfDC flakes explored here are of the order of tens of nanometres, thus preserving long polariton propagation.

Ultrahigh-k PhPs are typically observed only in hyperbolic materials, and the ultraconfined modes observed in HfSe2 are, indeed, hyperbolic. However, we also observe high-k propagating PhPs in HfS2 (λ0/70), which is elliptic in this spectral range27. To further understand such large confinement of both elliptic and hyperbolic PhPs, we examine the differences between polariton dispersions of HfS2 and HfSe2 based on experiments and simulations. For this purpose, we collected s-SNOM images at several excitation frequencies (ω0 = ck0), where ω0 and k0 are the free-space frequency and momentum, respectively, and plot the energy versus momentum dispersions, where k/k0 = λ0/λp (Fig. 2a,b). The experimental dispersions (black circles) are in good agreement with the simulated imaginary component of the p polarized reflectivity Im(rpp), which was calculated using the transfer matrix method36 based on the dielectric permittivities extracted from far-field experiments27. A dispersive mode is visible for both HfS2/SiO2 (Fig. 2a) and HfSe2/SiO2 (Fig. 2b), with the dispersions extending between 160–275 cm−1 and 120–190 cm−1, respectively. The two PhPs similarly start dispersing at lower frequencies before curving towards larger values of k. There, however, the hyperbolic mode maintains a finite slope as well as its strong Im(rpp) intensity, in contrast to its elliptic counterpart, which decays in intensity owing to higher losses and shifts towards a near-flat dispersion. Considering the long terahertz wavelengths and the nanoscale sample thicknesses, in both cases we are firmly in the ultrathin-film regime (d « λ0), where the elliptic surface PhPs hybridize to create a symmetric mode and an antisymmetric mode15,37. The symmetric mode, commonly referred to as epsilon-near-zero, generally exhibits a flat dispersion and exists at higher frequencies, whereas the antisymmetric mode (Fig. 2a), like plasmonic thin-film modes38, propagates with high k in thin films15. In the following, we focus on the antisymmetric mode of HfS2 because it has a dispersion with a finite slope that is very much like that of hyperbolic HfSe2 (compare Fig. 2a,b). The dispersion of the symmetric mode, instead, could be engineered with a superstrate that leads to strongly confined polaritons with a negative group-velocity dispersion16,21 (Supplementary Information, section 7).

a,b, PhP dispersions of HfS2/SiO2 (d = 68 nm) (a) and HfSe2/SiO2 (d = 68 nm) (b) thin films. Experimental data (black circles) are plotted over the simulated Im(rpp) illustrating the extremely large k of the propagating PhPs. Dashed lines show the in-plane TO and LO phonon frequencies, ωTO and ωLO, respectively, as reported previously27. c, Light confinement of the PhPs in HfSe2 as a function of substrate permittivity εsub. Confinement factors are calculated using the transfer matrix method with the flake thicknesses (d = 47, 68, 85 and 119 nm) used in the experimental s-SNOM imaging. Experimental values (circles) for HfSe2/SiO2 (εsub = 4 and ω0 = 165 cm−1) and HfSe2/Si (εsub = 12 and ω0 = 162 cm−1) are plotted along with the simulated values (solid lines, ω0 = 163.5 cm−1) for different HfSe2 thicknesses (for the colours, see the labels). d, Maximum confinement of thin-film polaritons of a type-II hyperbolic model material as a function of normalized light–matter coupling strength η at three fixed ratios of thickness to the free-space wavelength (d/λ0 = 2 × 10−3, black; 1 × 10−3, blue; and 5 × 10−4, red). See Supplementary Information, section 5 for details. Max., maximum; Min., minimum; Sim., simulated data.

The momenta of thin-film PhPs depend on the thickness, the polaritonic medium permittivity, and the substrate εsub and superstrate εsup permittivities15,16,18,21,39,40 (Supplementary Information, section 5). Our experimental data (Fig. 2c, circles) show an inverse relation between thickness and confinement for several flakes of HfSe2 (d = 47 nm, 68 nm, 85 nm or 119 nm), in agreement with the simulations (Fig. 2c, solid lines). The most highly confined PhPs (λ0/λp > 250) that we could resolve in our experiments were observed for the thinnest flake of HfSe2 on a Si substrate (εsub ≈ 12) at a frequency ω0 = 162 cm−1, because the polariton confinement increases with substrate permittivity εsub, in addition to the inverse scaling with film thickness (Fig. 2c). This also opens a route towards active tunability with phase change materials21,41. There is a limit, however, to how thin a film can be while still supporting the propagation of PhPs, which is defined as a PhP travelling at least one full wavelength before its amplitude decays by a factor of 1/e. At comparable thicknesses to our experiments, the maximum confinement of PhPs in mid-IR materials (for example, hBN and α-MoO3) plateaus around λ0/100 (refs. 18,20). Pushing to even thinner films does produce larger confinement1, but for mid-IR wavelengths, this approaches the atomic limit where propagation losses are too large for us to observe PhP modes. It is, therefore, interesting, instead, to use larger free-space wavelengths, rather than decreasing the film thickness, while still maintaining a small ratio between the two (d/λ0 « 1), making the terahertz range an ideal spectral range for testing the limits of ultraconfined PhPs. The key parameter for observing such ultraconfined thin-film polaritons at finite film thickness is the exceptionally large light–matter coupling of HfDCs in the terahertz spectral range. The light–matter coupling is quantified by the Rabi splitting (2g) between the upper and lower bulk polariton branches42 (Supplementary Information, section 5). These bulk PhPs exist at frequencies outside the RB, in contrast to the thin-film polaritons studied in this work, and are the result of ultrastrong coupling between infrared light and the infrared-active phonons of polar dielectrics43. On increasing the coupling strength g, the RB broadens, and the dispersion of the thin-film polaritons can extend out to larger momenta leading to larger confinement. To further generalize this phenomenon across different spectral ranges, we here employ the normalized light–matter coupling strength η that normalizes the Rabi splitting by the TO phonon frequency (ωTO):43

To analyse how η affects the polariton confinement, we simulate the PhP dispersion including propagation losses of a theoretical, type-II hyperbolic material. We calculate the maximum confinement (k/k0 at Re(k) = Im(k)), which is where propagation losses start to dominate, thus preventing propagation. We vary η by changing the LO–TO splitting while keeping the frequency of maximum confinement approximately constant (Supplementary Information, section 5). The resulting achievable confinement increases with η, as shown for three different thickness-to-wavelength ratios in Fig. 2d, and reaches the largest values for the thinnest films. Notably, both HfS2 and HfSe2 exhibit exceptionally large values of η ≈ 0.8, which explains the extreme confinement observed in our experiments. More generally, it is the combination of light–matter coupling strength, hyperbolicity and thickness-to-wavelength disparity that strongly enhances the confinement of polaritons in thin films.

Terahertz hyperlensing

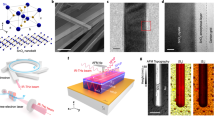

Beyond the extremely compressed wavelength of polaritons observed here, hyperbolic materials can additionally support higher-order modes whose superposition leads to diffractionless, ray-like polaritons travelling at distinct frequency-dependent angles within the volume of the crystal8,44 (Supplementary Information, sections 4 and 6). These effects, however, depend on the specific experimental geometry as to whether these polariton rays can contribute impactfully to the near-field images, as illustrated in Fig. 3. We illustrate the contrast in mode profiles by simulating the electric fields for elliptic and hyperbolic PhPs in thin films of HfS2 (Fig. 3a) and HfSe2 (Fig. 3b), respectively. We compare edge-launching for HfDC thin films placed on a SiO2 substrate (Fig. 3a,b, top) as well as launching by a Au disc (Fig. 3a,b, bottom), which acts like a nano-antenna that scatters incident light much more efficiently than the thin-film edge. The elliptic thin-film mode in HfS2 is launched by the edge of the thin film and the Au disc with identical wavelengths and similar profiles. The hyperbolic PhPs in HfSe2, launched by the thin-film edge (Fig. 3b, top), are dominated by the fundamental (M0) mode and very closely resemble their elliptic counterparts in this ultrathin-film regime. However, unlike in HfS2, we clearly resolve hyperbolic rays in HfSe2 when placed on the Au disc, which constitute the superposition of all higher-order modes45. We note that a weak ray can be also seen without the Au disc substrate, which is due to direct but less efficient excitation of these modes from the thin-film edge (Fig. 3b, top, inset). The thin-film edge, thus, mainly launches the fundamental M0 mode, which is visible in Fig. 1b. We note that there is also a narrow elliptic band in HfSe2 (~120–140 cm−1). However, this range is dominated by losses, and we were unable to observe PhPs (Supplementary Information, section 6).

a,b, Simulated, background-subtracted electric field magnitude of PhPs in thin films (d = 100 nm) of HfS2 (a) and HfSe2 (b) on SiO2 substrates. E is the electric field and Ebg the background field without Au discs and HfDCs. The PhP waves are excited by a parallel-polarized plane wave at 45° incidence angle with frequencies ω0 = 240 cm−1 (a) and ω0 = 165 cm−1 (b). The waves are scattered at the sharp edge of the thin film (top panels) or by a Au disc underneath the film (bottom panels). White double-headed arrows highlight different types of propagation giving rise to hyperlensing and thin-film modes. The propagation pattern of the thin-film mode arises from the constructive and destructive interference with the plane wave. Inset: zoom-in of a hyperbolic ray launched from the flake edge. c, Experimental top-view (x–y) s-SNOM images (top, ω0 = 240 cm−1) and simulated side view (x–z) of the electric field magnitude (bottom, x–z) for HfS2 in a hyperlensing configuration. A thin film of thickness 115 nm is placed on top of a Au disc of radius r = 500 nm. d, Similarly, s-SNOM images and simulated electric fields for HfSe2 in a hyperlensing geometry (ω0 = 168 cm−1).

The ray-like propagation of hyperbolic polaritons enables nanoscale hyperlensing and image magnification, owing to the rigid angle of polariton ray propagation. By employing HfDCs in a hyperlensing geometry, we experimentally demonstrate terahertz hyperlensing in Fig. 3c,d refs. 7,8. Thin flakes of HfS2 (Fig. 3c, d = 115 nm) and HfSe2 (Fig. 3d, d = 115 nm) were transferred onto a Au disc (r = 500 nm and h = 40 nm) and imaged with s-SNOM. The near-field patterns measured on the surfaces of the HfS2 (Fig. 3c, top, ω0 = 240 cm−1) and HfSe2 (Fig. 3d, top, ω0 = 168 cm−1) consist of bright ‘hot rings’ encircling the circumference of the Au disc (Fig. 3c,d, top, dashed circles), consistent with similar measurements reported for hBN7,8. However, another ring appears on the HfSe2 sample.This ring is within the circumference of the Au disc, indicating that, indeed, we observe terahertz hyperlensing for hyperbolic HfSe2 (see Supplementary Information, section 6 for frequency-dependent data and hyperlensing angles). We note that the dark spots in the s-SNOM intensity of HfSe2 (Fig. 3d, top) emerge from oxidation defects that are common for transition-metal selenides46, but interestingly, these do not seem to influence the polariton propagation by scattering or other deleterious interactions.

To corroborate these experimental observations, we show the simulated electric fields from a 2D side-view profile (x–z, Fig. 3c,d, bottom) for both cases, elliptic HfS2 and hyperbolic HfSe2. The Au disc scatters the incident light and strongly focuses the electric fields around the sharp edges, subsequently launching PhPs into the HfDC thin film above. For elliptic HfS2 at that frequency, only the antisymmetric thin-film mode is supported, and thus, the blurry ring corresponds to the first lobe of that wave and is observable only owing to the thin-film nature of the layer. By contrast, for hyperbolic HfSe2, the gold edge couples not only to the fundamental M0 but also to higher-order modes to form hyperbolic rays8,44 that propagate radially in both directions from the edge of the Au disc. The simulations confirm that, indeed, our results show hyperlensing in the terahertz range in a natural crystal, here indicating the imaging of a 1 μm-diameter particle, which is ×60 smaller than the free-space wavelength (59.5 μm).

Outlook and conclusion

Shrinking electromagnetic waves to subdiffractional mode volumes is essential for the development of nanophotonic devices, enhancing imaging capabilities and exploring nanoscale phenomena. In the infrared, the mechanisms to achieve high-k PhPs have primarily been reserved to identifying hyperbolic media or pushing light confinement to the absolute limit18,35. The observation of ultrahigh-k, broadband, elliptic and hyperbolic PhPs in HfS2 and HfSe2 in the terahertz range represents a considerable addition to the library of polaritonic materials. Moreover, it reveals the importance of the light–matter coupling strength, a material property that strongly influences the propagation of polaritons. The search for PhP materials with ultrastrong light–matter coupling strengths has largely been focused on the mid-IR, where polar dielectrics such as silicon carbide (SiC)47, α-MoO3 (ref. 23) and III nitrides18,48,49 display large LO–TO phonon splittings (>100 cm−1). A notable exception is SrTiO3, which has broad RBs from the terahertz to the mid-IR and, thus, provides an opportunity to explore ultraconfined PhPs in oxide membranes26. The RBs of several PhP materials are shown in Fig. 4a, which illustrates the difference in size between those in the mid-IR and terahertz. However, to fully understand the coupling strength of a polaritonic material, it is necessary to consider the magnitude of its phonon splitting relative to the TO phonon frequency. After calculating η for the same set of dielectrics (Fig. 4b), we find those values for HfS2 and HfSe2 to be nearly double those of most previously reported mid-IR materials, despite their smaller absolute RB widths. These large coupling strengths are the result of the exceptionally large Born effective charge magnitudes and the low TO frequencies27,28.

a, RBs (ωTO to ωLO) of several polar dielectric materials in the terahertz to mid-IR range. Anisotropic materials are represented by different colour bands, with isotropic materials by one band (blue), uniaxial materials by two bands (blue and red) and biaxial materials by three bands (blue, red and yellow). b, Normalized coupling strength η calculated with equation (1) for each material in a.

Despite the interest in the terahertz community regarding nanophotonic applications such as biomolecule fingerprinting50, medical diagnostics51 and thermal management52,53, traditional optics have restricted the spatial resolution of imaging and spectroscopy owing to the long free-space wavelengths. Furthermore, compressing electromagnetic fields to subdiffractional length scales results in high intensities, which introduces nonlinearities that may facilitate terahertz strong-field physics54. In this work, we imaged in real space ultrahigh-k terahertz PhPs (λ0/λp > 250) in 2D vdW crystals where the thickness does not approach the atomic limit (≥50 nm). The high normalized light–matter coupling strengths of HfDCs, which facilitate large confinement while avoiding deleterious losses, are highlighted as a crucial parameter that aids the identification of novel polaritonic materials. We have found that it is feasible to propagate terahertz light at the length scale of visible wavelengths, thus helping to push the field of nanophotonics to its limits.

Methods

Sample fabrication

Thin flakes were fabricated by mechanical exfoliation of HfSe2 and HfS2 bulk crystals (HQ Graphene) using the Scotch tape method55. Flakes were exfoliated onto either Si with an ~1-μm-thick oxide layer, which served as the SiO2 substrate, or high-resistivity float zone Si.

Hyperlens fabrication

Hyperlensing samples were fabricated by deterministically transferring 2D flakes of HfS2 and HfSe2 onto Au discs using a polymer-assisted transfer method. The discs were fabricated on a Si substrate using electron-beam lithography and resistive Au deposition. The discs had a thickness of 40 nm. HfDC flakes were mechanically exfoliated onto a Si substrate, removed using a polydimethylsiloxane stamp and transferred onto the Au discs.

FEL-SNOM

Polariton imaging was performed using an s-SNOM from Attocube Systems. The microscope is attached to the free-electron laser facility FELBE at the Helmholtz-Zentrum Dresden-Rossendorf, Germany33,34. The s-SNOM tip, with tapping frequency Ω ≈ 160 kHz, focuses the FEL radiation at its apex and scatters the signal into the far field. The scattered signal is composed of several harmonics (nΩ, n = 1, 2, 3, …), which are demodulated from the linear far-field background. A liquid helium-cooled gallium-doped germanium photoconductive detector (QMC Instruments Ltd) was used to detect the scattered signal. For the edge-launched polaritons, the second harmonic near-field signal (SO2A, n = 2) was recorded using either homodyne or self-homodyne interferometric detection, and the hyperlensing measurements were made using self-homodyne detection56. The experiments were conducted with a FEL because of its fully tunable and narrowband radiation. Future measurements of these materials could be conducted with narrowband table-top terahertz lasers at selected frequencies or with broadband terahertz light sources.

Transfer matrix simulations

The dispersion maps shown in Fig. 2 were calculated using a transfer matrix algorithm36. We evaluated the imaginary component of the parallel-polarized reflection coefficient for evanescent wave excitation at a given in-plane momentum k. Peaks in these maps correspond to absorptive polariton resonances36, whereas the linewidth of these peaks in horizontal cuts (at constant frequency) relate to the propagation losses and the linewidth in vertical cuts (at constant momentum) relate to the polariton lifetime. These quantities were used to estimate the maximum achievable confinement, as shown in Fig. 2d (see Supplementary Information, section 5 for details).

Full-wave finite-element simulations

Full-wave finite-element simulations were conducted with COMSOL Multiphysics using the electromagnetic waves, frequency-domain solver of the RF Module. A 2D simulation cell in the x–z plane (vertical cross section through the HfDC film) was constructed to simulate the hyperlensing or edge-launching experiments. Plane-wave illumination (normal incidence for hyperlensing) was used to excite PhPs. The simulation cell was surrounded by perfectly matched layers. We used the dielectric function of HfDCs from ref. 27 and set ε∞,z = 7 for HfSe2 for the hyperlensing simulation in Fig. 3d. The background electric field without the Au disc launcher or the HfDC was subtracted.

Data availability

All data that support the findings of this study are present in the main text and the Supplementary Information. All raw data generated during the current study are available from the corresponding authors upon request.

Code availability

The code used for the transfer matrix method in this study to calculate the polariton dispersions is available via Zenodo at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.601496 (ref. 57).

References

Li, N. et al. Direct observation of highly confined phonon polaritons in suspended monolayer hexagonal boron nitride. Nat. Mater. 20, 43–48 (2020).

Iranzo, D. A. et al. Probing the ultimate plasmon confinement limits with a van der Waals heterostructure. Science 360, 291–295 (2018).

Low, T. et al. Polaritons in layered two-dimensional materials. Nat. Mater. 16, 182–194 (2017).

Galiffi, E. et al. Extreme light confinement and control in low-symmetry phonon-polaritonic crystals. Nat. Rev. Mater. 9, 9–28 (2023).

Basov, D. N., Fogler, M. M. & García de Abajo, F. J. Polaritons in van der Waals materials. Science 354, aag1992 (2016).

de Abajo, F. J. G. et al. Roadmap for photonics with 2D materials. ACS Photonics 12, 3961–4095 (2025).

He, M. et al. Ultrahigh-resolution, label-free hyperlens imaging in the mid-IR. Nano Lett. 21, 7921–7928 (2021).

Dai, S. et al. Subdiffractional focusing and guiding of polaritonic rays in a natural hyperbolic material. Nat. Commun. 6, 6963 (2015).

Autore, M., Mester, L., Goikoetxea, M. & Hillenbrand, R. Substrate matters: surface-polariton enhanced infrared nanospectroscopy of molecular vibrations. Nano Lett. 19, 8066–8073 (2019).

He, M. et al. Guided mid-IR and near-IR light within a hybrid hyperbolic-material/silicon waveguide heterostructure. Adv. Mater. 33, 2004305 (2021).

Caldwell, J. D. et al. Low-loss, infrared and terahertz nanophotonics using surface phonon polaritons. Nanophotonics 4, 44–68 (2015).

Foteinopoulou, S., Devarapu, G. C. R., Subramania, G. S., Krishna, S. & Wasserman, D. Phonon-polaritonics: enabling powerful capabilities for infrared photonics. Nanophotonics 8, 2129–2175 (2019).

Dai, S. et al. Graphene on hexagonal boron nitride as a tunable hyperbolic metamaterial. Nat. Nanotechnol. 10, 682–686 (2015).

Ma, W. et al. In-plane anisotropic and ultra-low-loss polaritons in a natural van der Waals crystal. Nature 562, 557–562 (2018).

Mancini, A. et al. Near-field retrieval of the surface phonon polariton dispersion in free-standing silicon carbide thin films. ACS Photonics 9, 3696–3704 (2022).

Dubrovkin, A. M., Qiang, B., Krishnamoorthy, H. N. S., Zheludev, N. I. & Wang, Q. J. Ultra-confined surface phonon polaritons in molecular layers of van der Waals dielectrics. Nat. Commun. 9, 1762 (2018).

Álvarez-Pérez, G., Voronin, K. V., Volkov, V. S., Alonso-González, P. & Nikitin, A. Y. Analytical approximations for the dispersion of electromagnetic modes in slabs of biaxial crystals. Phys. Rev. B 100, 235408 (2019).

Dai, S. et al. Tunable phonon polaritons in atomically thin van der Waals crystals of boron nitride. Science 343, 1125–1129 (2014).

de Oliveira, T. V. A. G. et al. Nanoscale-confined terahertz polaritons in a van der Waals crystal. Adv. Mater. 33, e2005777 (2021).

Zheng, Z. et al. Highly confined and tunable hyperbolic phonon polaritons in van der Waals semiconducting transition metal oxides. Adv. Mater. 30, 1705318 (2018).

Li, P. et al. Reversible optical switching of highly confined phonon–polaritons with an ultrathin phase-change material. Nat. Mater. 15, 870–875 (2016).

Huang, J. et al. In-plane hyperbolic phonon-polaritons in van der Waals nanocrystals. Adv. Opt. Mater. 11, 2202048 (2023).

Álvarez‐Pérez, G. et al. Infrared permittivity of the biaxial van der Waals semiconductor α‐MoO3 from near‐ and far‐field correlative studies. Adv. Mater. 32, 1908176 (2020).

Nörenberg, T. et al. Germanium monosulfide as a natural platform for highly anisotropic THz polaritons. ACS Nano 16, 20174–20185 (2021).

Chen, S. et al. Real-space nanoimaging of THz polaritons in the topological insulator Bi2Se3. Nat. Commun. 13, 1374 (2022).

Xu, R. et al. Highly confined epsilon-near-zero and surface phonon polaritons in SrTiO3 membranes. Nat. Commun. 15, 4743 (2024).

Kowalski, R. A. et al. Mid‐ to far‐infrared anisotropic dielectric function of HfS2 and HfSe2. Adv. Opt. Mater. 10, 2200933 (2022).

Neal, S. N., Li, S., Birol, T. & Musfeldt, J. L. Chemical bonding and Born charge in 1T-HfS2. npj 2D Mater. Appl. 5, 45 (2021).

Folland, T. G., Nordin, L., Wasserman, D. & Caldwell, J. D. Probing polaritons in the mid- to far-infrared. J. Appl. Phys. 125, 191102 (2019).

Huber, A., Ocelic, N., Taubner, T. & Hillenbrand, R. Nanoscale resolved infrared probing of crystal structure and of plasmon-phonon coupling. Nano Lett. 6, 774–778 (2006).

Chen, X. et al. Modern scattering-type scanning near-field optical microscopy for advanced material research. Adv. Mater. 31, 1804774 (2019).

Kehr, S. C., Döring, J., Gensch, M., Helm, M. & Eng, L. M. FEL-based near-field infrared to THz nanoscopy. Synchrotron Radiat. News 30, 31–35 (2017).

Helm, M. et al. The ELBE infrared and THz facility at Helmholtz-Zentrum Dresden-Rossendorf. Eur. Phys. J. Plus 138, 158 (2023).

Álvarez-Cuervo, J. et al. Unidirectional ray polaritons in twisted asymmetric stacks. Nat. Commun. 15, 9042 (2024).

Woessner, A. et al. Highly confined low-loss plasmons in graphene–boron nitride heterostructures. Nat. Mater. 14, 421–425 (2014).

Passler, N. C. et al. Layer-resolved resonance intensity of evanescent polariton modes in anisotropic multilayers. Phys. Rev. B 107, 235426 (2023).

Passler, N. C. et al. Strong coupling of epsilon-near-zero phonon polaritons in polar dielectric heterostructures. Nano Lett. 18, 4285–4292 (2018).

Burke, J. J., Stegeman, G. I. & Tamir, T. Surface-polariton-like waves guided by thin, lossy metal films. Phys. Rev. B 33, 5186 (1986).

Lee, I.-H. et al. Image polaritons in boron nitride for extreme polariton confinement with low losses. Nat. Commun. 11, 3649 (2020).

Menabde, S. G. et al. Near-field probing of image phonon-polaritons in hexagonal boron nitride on gold crystals. Sci. Adv. 8, 627 (2022).

Jäckering, L. et al. Tailoring hBN’s phonon polaritons with the plasmonic phase-change material In3SbTe2. Preprint at https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2504.18418 (2025).

Barra-Burillo, M. et al. Microcavity phonon polaritons from the weak to the ultrastrong phonon–photon coupling regime. Nat. Commun. 12, 6206 (2021).

Mueller, N. S., Barros, E. B. & Reich, S. Ultrastrong light-matter coupling in materials. Preprint at https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2505.06373 (2025).

Herzig Sheinfux, H. et al. High-quality nanocavities through multimodal confinement of hyperbolic polaritons in hexagonal boron nitride. Nat. Mater. 23, 499–505 (2024).

Nikitin, A. Y. et al. Nanofocusing of hyperbolic phonon polaritons in a tapered boron nitride slab. ACS Photonics 3, 924–929 (2016).

Yao, Q., Zhang, L., Bampoulis, P. & Zandvliet, H. J. W. Nanoscale investigation of defects and oxidation of HfSe2. J. Phys. Chem. C 122, 25498–25505 (2018).

Tiwald, T. E. et al. Carrier concentration and lattice absorption in bulk and epitaxial silicon carbide determined using infrared ellipsometry. Phys. Rev. B 60, 11464–11474 (1999).

Collins, A. T., Lightowlers, E. C. & Dean, P. J. Lattice vibration spectra of aluminum nitride. Phys. Rev. 158, 833–838 (1967).

Torii, K. et al. An attenuated-total-reflection study on the surface phonon-polariton in GaN. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 12, 7041 (2000).

Bakker, J. M., Aleese, L. M., Meijer, G. & von Helden, G. Fingerprint IR spectroscopy to probe amino acid conformations in the gas phase. Phys. Rev. Lett. 91, 203003 (2003).

Adato, R., Yanik, A. A., Wu, C.-H., Shvets, G. & Altug, H. Radiative engineering of plasmon lifetimes in embedded nanoantenna arrays. Opt. Express 18, 4526 (2010).

Rephaeli, E., Raman, A. & Fan, S. Ultrabroadband photonic structures to achieve high-performance daytime radiative cooling. Nano Lett. 13, 1457–1461 (2013).

Pan, Z. et al. Remarkable heat conduction mediated by non-equilibrium phonon polaritons. Nature 623, 307–312 (2023).

Kampfrath, T., Tanaka, K. & Nelson, K. A. Resonant and nonresonant control over matter and light by intense terahertz transients. Nat. Photonics 7, 680–690 (2013).

Novoselov, K. S. et al. Electric field in atomically thin carbon films. Science 306, 666–669 (2004).

Keilmann, F. & Hillenbrand, R. Near-field microscopy by elastic light scattering from a tip. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A 362, 787–805 (2004).

Passler, N. C. & Paarman, A. Generalized 4x4 matrix algorithm for light propagation in anisotropic stratified media (MATLAB files). Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.601496 (2019).

Acknowledgements

R.A.K. acknowledges that this work was supported by a NASA Space Technology Graduate Research Opportunity. N.S.M. acknowledges funding from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (German Research Foundation; project 551280726). K.D.-G. was supported by the Army Research Office (grant W911NF-21-1-0119). A.S. acknowledges support from the Department of Energy, Basic Energy Sciences (grant DE-FG02-09ER4655). S.D. and J.D.C. were supported by the Office of Naval Research MURI on Twist-Optics (grant N0001-23-1-2567). P.A.-G. acknowledges support from the European Research Council (consolidator grant 101044461, TWISTOPTICS) and the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation (State Plan for Scientific and Technical Research and Innovation grant PID2022-141304NB-I00). M.O., F.G.K., J.W., L.M.E. and S.C.K. acknowledge financial support from the Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung (Federal Ministry of Education and Research, Germany, project grants 05K19ODB and 05K22ODA) and from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft under Germany’s Excellence Strategy through the Würzburg-Dresden Cluster of Excellence on Complexity and Topology in Quantum Matter—ct.qmat (grant EXC 2147, project 390858490) and through the Collaborative Research Center on Chemistry of Synthetic Two-Dimensional Materials (CRC1415, 417590517). The Au discs were fabricated as part of a user project at the Center for Nanophase Materials Sciences, which is a US Department of Energy, Office of Science User Facility at Oak Ridge National Laboratory.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Max Planck Society.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

R.A.K. and N.S.M. contributed equally. R.A.K. and I.I.K. fabricated the samples. R.A.K., N.S.M., G.A.-P., M.O., K.D.-G., G.C., A.S., S.D., R.N., R.B.I., F.G.K., J.W., J.M.K., T.G.F., A.P. and J.D.C. performed the experimental near-field imaging measurements. R.A.K., N.S.M., G.A.-P., M.O., T.G.F., A.P. and J.D.C. interpreted and analysed the polariton and hyperlensing data. N.S.M. performed the COMSOL simulations. R.A.K., N.S.M., K.D.C. and A.P. designed the graphical figures for the paper. A.P. and J.D.C supervised the project. All authors contributed to the preparation of the paper.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Materials thanks the anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Sections 1–7.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kowalski, R.A., Mueller, N.S., Álvarez-Pérez, G. et al. Ultraconfined terahertz phonon polaritons in hafnium dichalcogenides. Nat. Mater. 24, 1735–1741 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41563-025-02345-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41563-025-02345-0