Abstract

Achieving the efficient integration and synergy of multi-component polymers is an effective approach for the development of new polymer materials and breakthroughs in performance. However, there are still considerable challenges in achieving molecular-level integration of multi-component polymers. Here we report polymer chain entanglement through asymmetric entangled nodes, inspired by macroscopic woven materials with different warp and weft strands, achieving the integration of polyurethane and epoxy resin chains at the molecular level. The abundant dynamic entanglements within the polymer network, reminiscent of woven topologies, enable the flexible polyurethane chains and rigid epoxy chains to work synergistically under external stress, thereby imparting excellent mechanical and adhesive properties to the final network. This study demonstrates the potential of weaving-inspired molecular-level entanglement in polymer integration and performance modulation, while also providing an important reference for the design of novel multi-component polymeric materials through weaving-inspired strategies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

The advent of polymers, particularly synthetic polymers, has profoundly advanced human civilization by providing materials with unparalleled versatility and functionality1,2,3,4. However, the limitations inherent in single-type polymers often restrict their applicability in emerging application scenarios. To overcome these challenges, it is essential to merge multiple types of polymer, achieving efficient integration that combines the advantages and functions of diverse types of polymer5,6,7,8,9. Current polymer integration methods, such as blending and copolymerization, have been used to merge different polymers10,11,12,13,14,15, but they often fall short of achieving effective synergy owing to issues such as incompatibility and limited control over polymer chain distribution16,17,18. Consequently, these methods may not fully realize the potential of multi-component polymeric materials. This underscores the pressing need for innovative approaches to polymer integration that can seamlessly merge different polymer chains at the molecular level, unlocking new possibilities in polymeric material design.

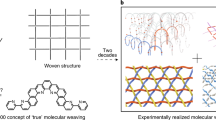

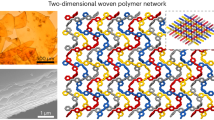

Weaving has been proven to be an efficient and versatile technique, where simple linear materials are entangled through the induction of numerous entangled nodes, achieving a high degree of integration and synergy between warp and weft segments, forming intricate and refined topological structures and imparting exceptional mechanical properties to the fabric materials19,20,21,22,23. Drawn by the fascinating structures and interesting properties of macroscopic weaving, chemists have been striving to incorporate weaving at the molecular level, with the goal of developing novel polymeric materials through bottom-up weaving control24. Since the Yaghi group reported the first example of woven covalent organic frameworks in 2016 (ref. 25), molecularly woven polymers have garnered widespread attention26,27,28,29. These pioneering efforts demonstrated that entanglement at the molecular level can effectively regulate the topological structures and mechanical properties of polymeric materials. It is noteworthy that macroscopic weaving not only regulates the structures and properties of materials but also integrates various types of functional fibre through entangled nodes, creating woven materials with diverse warp and weft threads that achieve a high degree of synergy among different materials30,31,32,33 (Fig. 1a). Inspired by this approach, we envisaged interlacing different polymer chains through molecularly entangled nodes, utilizing their dynamic synergistic effects akin to woven topologies to achieve effective integration of the polymer chains, thereby creating functional polymeric materials with enhanced performance. However, current research on woven polymer networks mainly focuses on molecular chains with identical components, leaving the challenge of leveraging weaving-inspired strategies to achieve efficient integration and synergy of different polymer chains at the molecular level unresolved.

a, A schematic representation of woven networks with the same (left) and different (right) warps and wefts. b, A schematic representation of the formation of polymer network WPU-EP crosslinked by weaving-inspired asymmetric entangled nodes. The asymmetric entangled nodes facilitate the efficient entanglement of flexible (PU) and rigid (EP) polymers, enabling molecular-level integration of their respective advantages and functions.

In the present work, we have achieved efficient integration and synergy of two types of polymer chain at the molecular level by utilizing the weaving-inspired asymmetric entangled nodes, resulting in a polymer network with exceptional performance. Specifically, we synthesized a bis-hydroxylated tridentate ligand (TL)34,35,36,37,38 and copolymerized it with polytetramethylene ether glycol (PTMG) and hexamethylene diisocyanate (HDI) to form a linear polyurethane (PU) containing tridentate binding sites (PUT). Subsequently, the coordinative binding between the tridentate binding sites in PUT and monodentate ligand (ML) was realized by the addition of palladium acetate, resulting in the highly efficient formation of asymmetric entangled nodes in the polymer chains (PUW). Finally, by copolymerizing the epoxy resin (EP) fragment E51 and the chain extender diamine (N,N′-dimethylethane-1,2-diamine, DMEDA) at the nodes of the PUW chains, the chain entanglements induced by the asymmetric entangled nodes facilitate the integration between the PU and EP chains, forming a polymer network (WPU-EP). The core of this approach involves using palladium (II) to create weaving-inspired asymmetric entangled nodes through coordination between tridentate and monodentate ligands, enabling the stepwise polymerization of PU and EP into a synergistic polymer network with the entanglements. In this network, the flexible PU segments and rigid EP segments are highly integrated through the mediation of the numerous entangled nodes (Fig. 1b). The movement and deformation of the flexible segments, along with dynamic entangled node dissociation and polymer segment slippage, provide the material with dynamic properties that effectively absorb and dissipate energy while dispersing stress under external forces. Meanwhile, both the rigid EP segments and the intricate entanglement topology serve as a skeleton to maintain the integrity of the topological network. Consequently, the efficient integration and synergy of flexible and rigid polymer chains at the entangled nodes impart excellent mechanical properties to the resulting network.

Design, synthesis and structural characterization

PU and EP are among the most commonly used polymeric materials in industrial production. PU polymers are typically known for their excellent elasticity and flexibility39,40. Conversely, EP, while exhibiting high strength and modulus after curing, has high brittleness and limited flexibility41,42. Therefore, in industrial applications, it is common to blend these two materials to enhance their overall performance and meet the demands of various harsh environments43,44,45. In this work, we selected PU and EP as examples to explore the synergy of topological entanglement in facilitating the integration of different polymers and enhancing their performance. We synthesized the WPU-EP network and, for comparison, also created CPU-EP and SPU-EP networks (Fig. 2f), with their primary distinction being the topological structures formed through entangled, covalent and supramolecular crosslinks, respectively (Supplementary Figs. 1–23 and Supplementary Tables 1–3).

The construction of WPU-EP hinges on inducing entanglement through weaving-inspired asymmetric entangled nodes. To validate the feasibility of interlaced coordination at the asymmetric entangled node, we successfully used model ligands to construct an asymmetric entangled node and analysed its crystal structure (Fig. 2a) using X-ray diffraction (Supplementary Table 6). The crystal structure presented in Fig. 2a demonstrates that, as expected, interlaced asymmetric coordination occurred in the presence of palladium(II), suggesting that this class of molecular entangled nodes can effectively induce the entanglement of different polymer chains. On this basis, the entangled crosslinked polymer network WPU-EP was obtained by stepwise polymerization of PU and EP chains via the polar functional groups at the end of the nodes. This polymeric material exhibits a transparent pale yellow colour and, due to the entanglement of the nodes, maintains structural stability. It does not dissolve after being immersed in N,N-dimethylformamide (DMF) for 24 h (Fig. 2b). The changes in characteristic functional group signals of the three polymer networks were also investigated in the condensed state by Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy. As shown in Fig. 2c, the peaks around 2,120 cm−1 corresponding to the NCO groups and 912 cm−1 corresponding to the epoxy groups disappeared completely in the all three polymer networks, indicating that both HDI and E51 in the systems have been completely reacted to construct polymeric networks. The peaks at 3,300–3,600 cm−1, 1,660–1,720 cm−1 and 1,010–1,250 cm−1 were assigned as the characteristic absorptions of N–H and O–H, C=O, and C–O–C, respectively, which demonstrates the formation of urethane groups and the introduction of a large number of hydroxyl groups in the EP chains. The peaks at 2,850–2,960 cm−1, 1,490–1,550 cm−1 and 810–830 cm−1 were ascribed as the stretching vibrations of CH2 and benzene rings and the bending vibrations of para-disubstituted benzene rings, indicating the successful integration of PU and EP segments in the networks. Moreover, the peak at 1,450 cm−1 ascribed to the pyridine groups of the nodes was found only in the spectra of WPU-EP and SPU-EP, demonstrating the presence of crosslinks in the networks.

a, The crystal structure of a weaving-inspired entangled node based on tridentate and monodentate ligands (model compounds) with palladium (II) via crossed asymmetric coordination. b, Photographs of a WPU-EP dumbbell-shaped sample and its state after 24 h of immersion in DMF. c, Attenuated total reflection Fourier transform infrared spectra of WPU-EP, SPU-EP and CPU-EP. d, DSC curves of WPU-EP, SPU-EP and CPU-EP recorded in the second heating scan from −85 °C to 80 °C with a heating rate of 10 °C min−1. Here ‘EXO Down’ means that the downward direction represents the exothermic direction. e, Swelling ratio histogram of WPU-EP, SPU-EP and CPU-EP in DMF. f, A schematic diagram of structural changes of polymer networks with different crosslinking patterns (CPU-EP, WPU-EP and SPU-EP) under mechanical deformation.

The segmental mobility within a polymer network is constrained by its crosslinking structure; therefore, differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) was performed on the three polymer networks to investigate their thermal transition behaviours. The endothermic peak formed by the melting of crystalline PTMG in the PU chains is located around 23 °C. The glass transition temperatures (Tg) of CPU-EP, WPU-EP and SPU-EP are −69.8 °C, −70.1 °C and −78.2 °C, respectively (Fig. 2d). These low Tg values are mainly attributed to the PU soft segments in the networks (Supplementary Fig. 29). At a higher temperature (65.6 °C), the SPU-EP sample exhibited another Tg, attributed to the EP polymer segments within the network. Due to the weaker constraints imposed by supramolecular crosslinking, the polymer chains in SPU-EP exhibit enhanced chain mobility, which facilitates partial phase separation resulting from the limited compatibility between PU and EP segments. A similar situation can also be observed in the PU/EP blend sample (Supplementary Fig. 30). However, this phenomenon was not observed in the WPU-EP sample with the same composition, implying that the induced entanglement of the entangled nodes enhances the integration of these two distinct polymers. The swelling curves of the three networks (Fig. 2e) also indicate that the more interchain entanglements within WPU-EP contributes to maintaining network stability, even though DMF partially disrupts the coordination bonds during the swelling process46. In general, the introduction of topological entanglements brings the two polymer chains closer together while preserving the dynamics of the structure, thereby creating favourable conditions for their synergistic effects (Fig. 2f).

Mechanical properties of WPU-EP, SPU-EP and CPU-EP

To explore the effect of the entangled structure on the strength and toughness of integrated polymer networks of PU and EP, a series of mechanical property tests were carried out on a WPU-EP sample, a CPU-EP sample and an SPU-EP sample. As shown in Fig. 3a, the CPU-EP sample possesses the highest Young’s modulus (76.1 MPa) among the three samples (SPU-EP is 66.3 MPa and WPU-EP is 67.8 MPa) due to covalent crosslinking, while its stretchability is the lowest at 771% due to the lack of dynamic properties of the crosslinks, with a maximum stress of 25.8 MPa. The SPU-EP sample, through supramolecular crosslinking, exhibited a maximum stress of 25.4 MPa and a stretchability of 1937%. However, despite a remarkable improvement over CPU-EP, its stretchability value remains considerably lower than that (3105%) of WPU-EP, probably due to insufficient integration of the PU and EP components under supramolecular crosslinking, which leads to progressive fracture of both crosslinking points and the network structure. When the polymer network was crosslinked by entangled nodes, WPU-EP achieved an ultrahigh strain at break of 3,105% with a maximum stress of 63.3 MPa. This may be attributed to the entangled nodes based on metal coordination, which improve structural dynamics under external forces and enhance the entanglement of polymer chains, facilitating the integration of two originally incompatible polymers and achieving their synergistic effect (Supplementary Fig. 38). Benefitting from its excellent tensile and structural strengths, WPU-EP achieved an exceptionally high toughness of 989 MJ m−3, substantially higher than CPU-EP (142 MJ m−3) and SPU-EP (308 MJ m−3). Combined with the results of the cyclic stress–strain tests (Fig. 4e and Supplementary Figs. 41–55), WPU-EP showed better performance in terms of toughness, maximum stress, elongation at break, fatigue resistance and recoverability (Fig. 3b), suggesting that weaving-inspired entangled nodes have a unique advantage in constructing multi-component polymer networks.

a, Stress–strain curves recorded with a deformation rate of 50 mm min−1 of WPU-EP, CPU-EP and SPU-EP. b, A comparison of the mechanical properties of WPU-EP, CPU-EP and SPU-EP. c, Normalized stress relaxation curves of WPU-EP, CPU-EP and SPU-EP measured at 130 °C. d, Arrhenius plots of the stress relaxation time for WPU-EP, CPU-EP and SPU-EP samples. Dashed lines indicate a linear fit to the data. e,f, Dynamic mechanical analysis temperature sweeps of WPU-EP (e) and SPU-EP (f). g, Test schematic of oscillatory shear followed by frequency sweep to reveal the microscopic information of the topological entanglements in polymer networks. h, Moduli of WPU-EP versus the step time measured by oscillatory shear. i, Frequency sweep for WPU-EP and SPU-EP after the oscillatory shears of 0.2% and 600% to display the recovery process of the networks. j, Stress–strain curves recorded with a deformation rate of 50 mm min−1 of the demetallized WPU-EP and SPU-EP. k, Moduli at a frequency of 1.2 rad s−1 as a function of strains extracted from the frequency sweep results of the demetallized samples.

Exploring the stress relaxation behaviour of a polymer network can be an effective indicator of the characteristics of changes in the network structure under stress conditions. As shown in Fig. 3c and Supplementary Fig. 56, WPU-EP retained most of the stress below 110 °C, but the stress relaxation was gradually evident as the temperature continued to increase. This relaxation, however, did not completely release the stress in the network, quite different from SPU-EP, which relaxed almost completely within 10 s at 130 °C, and CPU-EP, which did not change appreciably with temperature (Supplementary Figs. 57 and 58). This difference is mainly attributed to the variation in the crosslinking mode, which consequently leads to the difference in the connectivity state of the polymer chains in the networks. We attempted to quantitatively evaluate the differences in the stability of the three networks by calculating their network activation capacities, derived from Arrhenius fitting of their stress relaxation data. As shown in Fig. 3d, the activation energies of WPU-EP, CPU-EP and SPU-EP were 32.4 kJ mol−1, 59.0 kJ mol−1 and 19.5 kJ mol−1, respectively, suggesting that the covalently crosslinked network is the most stable, whereas the topologically entangled network is superior to the supramolecular crosslinked network as indicated in other experiments (Supplementary Figs. 31–37).

To understand the role of the entangled nodes in the polymer network, we performed a temperature scan on all three polymer networks using a tensile mode of dynamic mechanical analysis. In Fig. 3e, the storage modulus E′ of WPU-EP showed a steady and continuous decrease after a plateau as the temperature increased from −100 °C to 150 °C. Meanwhile, the loss modulus E″ also exhibited a decreasing trend with increasing temperature after a small increase. As a result, the loss factor tan δ formed a broad peak around −45 °C, which is mainly attributed to the PU soft segments in the network. A similar phenomenon was also observed in the result of CPU-EP (Supplementary Fig. 60). Moreover, the subsequent rapid decline in E′ of all samples within the temperature range of −10 °C to 30 °C is mainly attributed to the melting of crystalline PTMG. However, a unique notable difference was observed in SPU-EP (Fig. 3f), that is, a peculiar rising interval in its E″ curve around 50 °C, causing tan δ to gain a new peak around 50 °C, which should be attributed to the EP segments within the network. This finding confirms the results of the DSC analysis, indicating that the entanglement of polymer chains induced by the nodes can effectively integrate the immiscible PU and EP segments, thereby suppressing phase separation within the network.

To further investigate the practical behaviour of topological entanglements within the network, we conducted large-amplitude oscillatory shear (LAOS) experiments (Fig. 3g). The moduli of oscillatory shear against the step time for WPU-EP and SPU-EP are shown in Fig. 3h and Supplementary Fig. 64, respectively. It could be found that WPU-EP and SPU-EP showed different trends in the variation of the modulus with time during a single LAOS stage (as indicated by the red arrows). Using the modulus at a strain of 600% as an example, the storage modulus G′ of WPU-EP exhibited an increasing trend over time, while that of SPU-EP showed a gradual decrease. This difference primarily stems from the distinct deformation behaviours of the two polymer networks under tensile stress. In WPU-EP, the presence of topological entanglements allows the entangled polymer chains to tighten and slip under stress while maintaining the overall network integrity. Moreover, the entangled topology enables efficient stress transfer throughout the network, thereby contributing to an increase in modulus. By contrast, the polymer chains in the SPU-EP network are crosslinked through relatively weak supramolecular nodes, which dissociate under applied stress, thereby triggering plastic deformation of the polymer. Therefore, as shown in Supplementary Figs. 62 and 65, when correlating the network moduli with the applied strains, the modulus of WPU-EP exhibits an initial decrease with increasing strain, followed by a plateau at approximately 150%. This indicates that the entangled nodes in the WPU-EP network endowed the structure with dynamics, and the presence of the high-density chain entanglements induced by these nodes hindered the further deformation of the network, thus maintaining the stability of the network structure. On the contrary, without the restraining effect of chain entanglements, the moduli of SPU-EP continuously decreased with the increase of applied strains, indicating the continuous deformation of the network. The frequency sweep results (Fig. 3i and Supplementary Figs. 63 and 66) indicate that the deformed network of WPU-EP has a faster recovery rate. Moreover, the continuous cyclic shear tests of WPU-EP and SPU-EP also demonstrated the crucial role of the polymer chain entanglements induced by the cross nodes in the structural stability of the network (Supplementary Figs. 67 and 68).

Subsequently, the demetallized WPU-EP and SPU-EP samples were prepared to further explore the influence of polymer chain entanglements on the properties of the polymer networks (Supplementary Figs. 24–28 and Supplementary Table 4). As shown in Fig. 3j, after the removal of metal ions, both the maximum stress (from 25.4 MPa to 15.5 MPa) and the elongation at break (from 1,937% to 1,092%) of SPU-EP dramatically decreased. Moreover, the demetallized SPU-EP shares similarities with the PU/EP blend sample in many aspects, including the swelling ratio, mechanical properties, phase separation state and so on (Supplementary Figs. 30, 31, 39, 40 and 61). By contrast, for WPU-EP, only the maximum stress decreased (from 63.3 MPa to 39.9 MPa), while the stretchability showed little change (from 3,105% to 2,989%). The primary reason for this phenomenon lies in the fact that, after the removal of metal ions, the polymer network can no longer dissipate energy through the breaking of coordination bonds under stress, resulting in a noticeable decrease in maximum stress (Supplementary Figs. 69‒74). However, despite the removal of metal ions, numerous chain entanglements remain within the polymer network, which help maintain the structural integrity during stretching and thereby preserve its excellent tensile performance. As indicated by the frequency sweep results after oscillatory shear at different strains, the demetallized WPU-EP maintained a stable modulus even at a strain of 300%, whereas the demetallized SPU-EP showed a marked reduction in modulus at strains as low as 50% (Fig. 3k and Supplementary Figs. 75–78).

Collectively, the weaving-inspired asymmetric entangled nodes formed via metal coordination play multiple critical roles in the polymer network. The metal–ligand coordination within these nodes strengthens intermolecular interactions across the network and provides effective energy dissipation pathways through the reversible dissociation of coordination bonds under stress. More importantly, the presence of these entangled nodes induces additional topological entanglements between polymer chains, which not only enhance the compatibility between otherwise immiscible polymer segments, but also promote their synergistic interactions through the mediating role of the entangled nodes. These synergistic mechanisms enable the polymer network to effectively avoid brittle failure and reduce plastic deformation under stress, resulting in a remarkable enhancement in its mechanical performance.

Insights into the properties of WPU-EP

To further investigate the impact of entangled nodes on the properties of the polymers, we first prepared a series of WPU-EP samples with varying node proportions of 1%, 5% and 10%. As shown in Fig. 4a,b, the maximum stress and break strain of these samples experienced a huge undulation from 8.7 MPa and 276%, to 63.3 MPa and 3,105%, to 21.7 MPa and 966% as the proportion of nodes increased from 1% to 5% and to 10%. This behaviour is primarily due to the influence of the node content on the crosslinking density of the polymer network. Specifically, insufficient entangled nodes result in inadequate confinement of polymer chain entanglement, leading to a loosely structured network and a more pronounced tendency for phase separation (Supplementary Fig. 82). Conversely, excessive crosslinking creates a tightly crosslinked network that restricts a wide range of dynamic behaviours. The result of the cyclic tensile tests (Supplementary Figs. 79–81) also indicates that the increase in metal-coordinated entangled nodes enhances energy dissipation due to dynamic dissociation under extra stress.

a,c, Stress–strain curves of WPU-EP samples with different proportions of entangled nodes (a) and different EP contents (c). b,d, Maximum stress and breaking elongation of WPU-EP samples with varying proportions of crosslinked nodes (b) and EP contents (d) in the network. e,f, Cyclic tensile tests without an interval for WPU-EP samples with 15% (e) and 50% (f) EP contents under strains of 50%, 100%, 150% and 200%. g, Damping capacities of WPU-EP samples with different EP contents calculated based on their cyclic tensile tests. h, The loss factor of WPU-EP samples with different EP contents from 0 °C to 120 °C. i, Arrhenius plots of the stress relaxation times for WPU-EP samples with different EP contents. Dashed lines indicate a linear fit to the data. j, Photograph of a WPU-EP sample in a dumbbell lifting experiment. The sample (EP% = 15%) was used directly for lifting as an elastomer.

Subsequently, we further investigated the impact of the EP content on the network performance by preparing a series of WPU-EP samples with varying EP contents of 15%, 20%, 30%, 50% and 70%. We initially conducted stress–strain tests on these samples. In Fig. 4c,d, we found that the elongation at break, maximum stress and toughness of the samples exhibited a continuous decrease with increasing the EP content in the network; for example, the maximum stress decreased from 63.3 MPa to 7.91 MPa. In the cyclic tensile tests, the damping capacity, residual strain and recovery capacity of these samples gradually increased with increasing EP content (Fig. 4e–g and Supplementary Figs. 83–97). This finding suggests that the performance of the polymeric network constructed from asymmetric nodes can be effectively tuned by controlling the contents of different polymer components, enabling adaptation to various application needs. To investigate the cause of this effect, we measured and analysed the loss factors of the samples. In Fig. 4h, as the EP content in the network increases, the peak of tan δ gradually intensifies within the temperature range of 50 °C to 80 °C. This indicates that, as the EP content continues to increase, the phenomenon of phase separation within the polymer network becomes more pronounced (Supplementary Fig. 98). Moreover, increasing the content of rigid EP segments in the network led to greater overall rigidity and a higher activation energy barrier (Fig. 4i). Based on the above experimental results, we preferred the WPU-EP sample with a 5% node proportion and 15% EP content, which has the highest tensile strength and toughness, for the dumbbell lifting experiment. In Fig. 4j and Supplementary Movie 1, a WPU-EP sheet of only 46 mg was used to easily lift a 3-kg dumbbell, whose weight is more than 65,200 times higher than its own mass, reflecting the great potential of asymmetric entangled nodes in the construction of multi-component polymeric networks.

Adhesion properties of PU-epoxy composites

EP is widely used in the bonding field because of its excellent adhesion, but its excessive rigidity is prone to brittle fracture under stress, necessitating the addition of flexible polymers to enhance its toughness. Encouraged by the above-discussed experimental results, we formulated an adhesive based on WPU-EP and compared it with a control adhesive that uses EP toughened by a marketed PU-based toughener, with the specific preparation steps of the adhesives shown in the Supplementary Information. The tensile strength was tested using aluminium as the substrate (Fig. 5a). The tensile strength of the WPU-EP-based adhesive was slightly higher than that of the control adhesive, and the stiffness was lower (Fig. 5b,c and Supplementary Table 5). Overall, the WPU-EP-based samples exhibited adhesive properties comparable to those of commercially available, traditional covalently crosslinked networks.

a, Tensile pattern for adhesion performance testing. b,c, Adhesion strength–displacement curves (b) and data for tensile strengths and displacements (c) of WPU-EP and control adhesives, obtained from the adhesion performance tests, with aluminium as the substrate. d, Lap-shear pattern for adhesion performance testing and the deformation mechanism of the polymeric network in the WPU-EP adhesive during the test. e, A photograph of the WPU-EP adhesive sample in the vehicle traction experiment. f,g, Adhesion strength–displacement curves (f) and data for tensile strengths and displacements (g) of WPU-EP and control adhesives obtained from the lap-shear tests. h, Literature comparison on tensile and shear strengths of copolymeric materials in recent years.

Unlike tensile strength, which primarily depends on the intrinsic bonding ability of the material, shear strength is more influenced by the toughness of the adhesive’s internal structure. This is due to the uneven and localized stress concentrations within the sample, resulting from changes in the direction of the applied external force (Fig. 5d). Therefore, we tried to evaluate the state of the samples under different force modes to verify the stability of the bonding. In Supplementary Fig. 99, a 5-kg dumbbell was easily lifted by two aluminium plates bonded over an area of just 2.5 cm × 1.3 cm. Remarkably, with the same bonding area, a car weighing up to 2.1 tons was successfully towed using two aluminium pieces joined by the WPU-EP adhesive. The traction remained stable, unaffected by rapid stress fluctuations caused by road undulations (Fig. 5e and Supplementary Movie 2). Moreover, after the traction was completed, the braking of the trailing vehicle caused a sudden increase in tensile force, resulting in the breakage of the traction rope, while the bonded area showed no abnormalities (Supplementary Fig. 100), indicating that the bonding performance of the WPU-EP adhesive is excellent and of great practical value. The shear strength, 15.1 MPa, of WPU-EP is much higher than that, 6.82 MPa, of the control (Fig. 5f,g), but with lower stiffness. From the bonding areas after the break (Supplementary Fig. 101), we can conclude that the bond is strong and efficient, and its rupture should also be attributed to the cohesive destruction of the polymer itself. Overall, the induced entanglement from asymmetric nodes enables the efficient integration of PU and EP, leading to the development of an excellent adhesive that combines high tensile and shear strength47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55 (Fig. 5h).

Conclusions

In this study, we achieved the efficient integration of two polymers—PU and epoxy resin—through crosslinked entanglement induced by weaving-inspired asymmetric entangled nodes. The flexible PU segments and rigid epoxy segments work synergistically under the influence of the entangled nodes, resulting in a polymeric network with excellent mechanical properties and adhesion performance. More importantly, we advanced the concept of weaving-inspired polymer networks from single-component systems to multi-component systems. This progression allows the entanglement and integration of different types or functionalities of polymeric material through entangled nodes, enabling multi-component and multi-functional synergy, and providing insights and references for the development of novel polymeric materials. We believe that the integration of polyurethane and epoxy resin, enabled by weaving-inspired asymmetric entangled nodes, marks only the beginning. We look forward to exploring further combinations of diverse polymers to fully realize the vast potential of molecular weaving in the design of novel polymeric materials.

Methods

Materials

All reagents used in this research were commercially available and used as supplied by the manufacturer without further purification. Organic solvents were evaporated under reduced pressure on an Eyela rotary evaporator using a water bath (50 °C). All reactions were performed at ambient laboratory conditions, and no precautions were taken to exclude atmospheric moisture unless otherwise specified. 4-{[N-(Boc)methylamino]methyl}phenol was prepared according to literature procedures56.

Mechanical tests

The mechanical properties of the polymers were measured using an Instron 34SC-1 instrument in standard stress–strain experiments. Toughness values (total toughness) were obtained by integrating the area under the corresponding stress–strain curves. Energy dissipation (dissipated toughness) was calculated by integrating the area encompassed by the cyclic tensile curves. Damping capacity was defined as the ratio of the dissipated energy (the area encompassed by the loading and unloading curves) to the loading energy (the area encompassed by the loading curve). Fatigue resistance was defined as the ratio of the maximum stress after multiple stretches to the initial maximum stress. Recovery ratio was defined as the ratio of the difference between the set deformation and the residual deformation after unloading to the set deformation.

Synthesis of the samples

For WPU-EP, all the reactants were fed in certain ratios as shown in Supplementary Table 3. First, E51 was added to a solution of PUW in a CH2Cl2/MeCN mixture (3:1, about 20 ml). After the contents were well mixed (about 3 h) and the solution was concentrated to around 2 ml, DMEDA was added and the mixture was stirred well again. After stirring for 3 h, the mixture was poured into a polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) plate, which was subsequently put in an oven at 80 °C for 12 h to allow the reaction to complete. Thus, a WPU-EP film was obtained.

For SPU-EP, P1 (5% node proportion, about 920 mg) was added to a solution of P2 (186 mg) in dry CH2Cl2 (10 ml). The solution was stirred vigorously for 2 h. The volatiles were removed under reduced pressure, and the mixture was poured into a PTFE plate. Then, the plate was put in an oven at 80 °C for 12 h to allow the reaction to complete. Thus, a SPU-EP film was obtained.

For CPU-EP, E51 (140 mg, 357 μmol) was added to a glue solution of P3 (all the resulting P3 product, about 0.91 g) in dry CH2Cl2 (10 ml). To avoid the occurrence of side reactions between the residual isocyanate groups and DMEDA, the mixture was thoroughly stirred for 6 h to ensure a complete reaction between P3 and E51. Then, after the solution was concentrated to around 2 ml, DMEDA (31.0 mg, 352 μmol) was added and the mixture was stirred well again. After 3 h, the mixture was poured into a PTFE plate, which was subsequently put in an oven at 80 °C for 12 h to allow the reaction to complete. Thus, a CPU-EP film was obtained.

For the PU/EP blend sample, PUT (about 910 mg) was added to a solution of P2 (186 mg) in dry CH2Cl2 (10 ml). The solution was stirred vigorously for 2 h. The volatiles were removed under reduced pressure, and the mixture was poured into a PTFE plate. Then, the plate was put in an oven at 80 °C for 12 h to allow the reaction to complete. Thus, the PU/EP blend samples were obtained.

For the demetallized samples, the films of WPU-EP and SPU-EP were immersed in 5 ml of a tetrabutylammonium cyanide solution (1 M solution in MeOH) for 24 h at room temperature, followed by sequential washing with 20 ml of MeOH three times. Then, the films were dried in an oven at 50 °C for 12 h to obtain the demetallized samples.

LAOS experiments

Initially, a frequency sweep from 300 to 1.2 rad s−1 within the linear viscoelastic regime (strain 0.2%) was performed to record the sample’s baseline viscoelastic response. Subsequently, the following procedure was cyclically applied: (1) an oscillatory shear (preshear) with a defined strain amplitude (γ) was applied for 300 s to induce mechanical motion of the network nodes and deformation of the polymer matrix, and (2) immediately after the preshear, a frequency sweep (300 to 1.2 rad s−1, strain 0.2%) was conducted to capture the altered viscoelastic state of the network. This cycle was repeated 16 times with increasing strain amplitudes ranging from 0.2% to 700%, without any interval between successive cycles.

Data availability

All data are available in the Article or its Supplementary Information. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Sun, J.-Y. et al. Highly stretchable and tough hydrogels. Nature 489, 133–136 (2012).

Lutz, J.-F., Ouchi, M., Liu, D. R. & Sawamoto, M. Sequence-controlled polymers. Science 341, 1238149 (2013).

Vatankhah-Varnosfaderani, M. et al. Mimicking biological stress–strain behaviour with synthetic elastomers. Nature 549, 497–501 (2017).

Sun, F. et al. Soft fiber electronics based on semiconducting polymer. Chem. Rev. 123, 4693–4763 (2023).

Wu, W. et al. Efficient and modular biofunctionalization of thiophene-based conjugated polymers through embedded latent disulfide. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 578–585 (2023).

Wu, X. et al. All-polymer bulk-heterojunction organic electrochemical transistors with balanced ionic and electronic transport. Adv. Mater. 34, 2206118 (2022).

Ai, L. et al. Tough soldering for stretchable electronics by small-molecule modulated interfacial assemblies. Nat. Commun. 14, 7723 (2023).

Yang, K. et al. Suprasomes based on host–guest molecular recognition: an excellent alternative to liposomes in cancer theranostics. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202213572 (2022).

Yang, Q. et al. Photocurable bioresorbable adhesives as functional interfaces between flexible bioelectronic devices and soft biological tissues. Nat. Mater. 20, 1559–1570 (2021).

Fujisawa, Y. et al. Blending to make nonhealable polymers healable: nanophase separation observed by CP/MAS 13C NMR analysis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202214444 (2022).

Yokoyama, K. & Guan, Z. A vitrimer acts as a compatibilizer for polyethylene and polypropylene blends. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 63, e202317264 (2024).

Deng, M. et al. Improving miscibility of polymer donor and polymer acceptor by reducing chain entanglement for realizing 18.64 % efficiency all polymer solar cells. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 63, e202405243 (2024).

Peng, Z. et al. Unraveling the stretch-induced microstructural evolution and morphology–stretchability relationships of high-performance ternary organic photovoltaic blends. Adv. Mater. 35, 2207884 (2022).

Chen, H. et al. Photocleavable polymer cubosomes: synthesis, self-assembly, and photorelease. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 14776–14784 (2024).

Matyjaszewski, K. & Tsarevsky, N. V. Nanostructured functional materials prepared by atom transfer radical polymerization. Nat. Chem. 1, 276–288 (2009).

Kim, G. U. et al. Highly efficient and robust ternary all-polymer solar cells achieved by electro-active polymer compatibilizers. Adv. Energy Mater. 13, 2302125 (2023).

Zhang, H., Zoubi, A. Z., Silberstein, M. N. & Diesendruck, C. E. Mechanochemistry in block copolymers: new scission site due to dynamic phase separation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202314781 (2023).

Lin, Z., Li, M., Yoshioka, R., Oyama, R. & Kabe, R. Oxygen-tolerant near-infrared organic long-persistent luminescent copolymers. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 63, e202314500 (2024).

Peng, Y. et al. Hierarchically structured and scalable artificial muscles for smart textiles. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 13, 54386–54395 (2021).

Zhao, Y. et al. Two-dimensional carbon nanotube woven highly-stretchable film with strain-induced tunable impacting performance. Carbon 189, 539–547 (2022).

Zhang, L. et al. Hierarchical weaving metafabric for unidirectional water transportation and evaporative cooling. Adv. Funct. Mater. 33, 2307590 (2023).

Zhang, D. et al. A dual gelation strategy under gravity-enhanced orientation to construct super-strong and tough bacterial cellulose phase change fiber for wearable heat supply. Adv. Funct. Mater. 35, 2413361 (2024).

Lan, L. et al. Woven organic crystals. Nat. Commun. 14, 7582 (2023).

Zhang, Z.-H., Andreassen, B. J., August, D. P., Leigh, D. A. & Zhang, L. Molecular weaving. Nat. Mater. 21, 275–283 (2022).

Liu, Y. et al. Weaving of organic threads into a crystalline covalent organic framework. Science 351, 365–369 (2016).

Li, G. et al. Robust and dynamic polymer networks enabled by woven crosslinks. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202210078 (2022).

Li, G. et al. Woven polymer networks via the topological transformation of a [2]catenane. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 14343–14349 (2020).

August, D. P. et al. Self-assembly of a layered two-dimensional molecularly woven fabric. Nature 588, 429–435 (2020).

Han, X. et al. Molecular weaving of chicken-wire covalent organic frameworks. Chem 9, 2509–2517 (2023).

Fan, W. et al. Sweat permeable and ultrahigh strength 3D PVDF piezoelectric nanoyarn fabric strain sensor. Nat. Commun. 15, 3509 (2024).

Yang, Y. et al. A non-printed integrated-circuit textile for wireless theranostics. Nat. Commun. 12, 4876 (2021).

Shi, X. et al. Large-area display textiles integrated with functional systems. Nature 591, 240–245 (2021).

Cho, S., Chang, T., Yu, T., Gong, S. L. & Lee, C. H. Machine embroidery of light-emitting textiles with multicolor electroluminescent threads. Sci. Adv. 10, eadk4295 (2024).

Fuller, A. M. et al. A 3D interlocked structure from a 2D template: structural requirements for the assembly of a square-planar metal-coordinated [2]rotaxane. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 43, 3914–3918 (2004).

Leigh, D. A., Lusby, P. J., Slawin, A. M. Z. & Walker, D. B. Rare and diverse binding modes introduced through mechanical bonding. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 44, 4557–4564 (2005).

Fuller, A. M. L., Leigh, D. A. & Lusby, P. J. One template, multiple rings: controlled iterative addition of macrocycles onto a single binding site rotaxane thread. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 46, 5015–5019 (2007).

Fuller, A.-M. L., Leigh, D. A., Lusby, P. J., Slawin, A. M. Z. & Barney, W. D. Selecting topology and connectivity through metal-directed macrocyclization reactions: a square planar palladium [2]catenate and two noninterlocked isomers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 127, 12612–12619 (2005).

Yamamoto, K., Nameki, R., Sogawa, H. & Takata, T. Macrocyclic dinuclear palladium complex as a novel doubly threaded [3]rotaxane scaffold and its application as a rotaxane cross-linker. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59, 18023–18028 (2020).

Gao, Z., Lou, Z., Han, W. & Shen, G. A self-healable bifunctional electronic skin. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 12, 24339–24347 (2020).

Qu, W.-Q., Xia, Y.-R., Jiang, L.-J., Zhang, L.-W. & Hou, Z.-S. Synthesis and characterization of a new biodegradable polyurethanes with good mechanical properties. Chin. Chem. Lett. 27, 135–138 (2016).

Shao, L. et al. Bona fide upcycling strategy of anhydride cured epoxy and reutilization of decomposed dual monomers into multipurpose applications. Chem. Eng. J. 464, 142735 (2023).

Chen, Z. et al. Application of epoxy resin in cultural relics protection. Chin. Chem. Lett. 35, 109194 (2024).

Zhang, S., Sun, Y. & Xu, J. 3-Mercaptopropyl)triethoxysilane-modified reduced graphene oxide-modified polyurethane yarn enhanced by epoxy/thiol reactions for strain sensors. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 13, 34865–34876 (2021).

Zhang, Z. et al. Co-enhancement of toughness and strength of room-temperature curing epoxy adhesive derived from hydroxyl-terminated polybutadiene based polyurethane resin. Eur. Polym. J. 219, 113373 (2024).

Lin, S. P., Han, J. L., Yeh, J. T., Chang, F. C. & Hsieh, K. H. Composites of UHMWPE fiber reinforced PU/epoxy grafted interpenetrating polymer networks. Eur. Polym. J. 43, 996–1008 (2007).

Ogawa, M., Kawasaki, A., Koyama, Y. & Takata, T. Synthesis and properties of a polyrotaxane network prepared from a Pd-templated bis-macrocycle as a topological cross-linker. Polym. J. 43, 909–915 (2011).

Park, H., Lim, D., Lee, G., Baek, M. J. & Lee, D. W. Tailoring pressure sensitive adhesives with H6XDI-PEG diacrylate for strong adhesive strength and rapid strain recovery. Adv. Funct. Mater. 33, 2305750 (2023).

An, H. et al. Hydrophobic cross-linked chains regulate high wet tissue adhesion hydrogel with toughness, anti-hydration for dynamic tissue repair. Adv. Mater. 36, 2310164 (2023).

Yang, Y. et al. Biomimetic, stiff, and adhesive periosteum with osteogenic–angiogenic coupling effect for bone regeneration. Small 17, 2006598 (2021).

Luo, S. et al. Supramolecular/dynamic covalent design of high-performance pressure-sensitive adhesive from natural low-molecular-weight compounds. Small 20, 2310839 (2024).

Zhang, B., Zhang, P., Zhang, G., Ma, C. & Zhang, G. Sterically hindered oleogel-based underwater adhesive enabled by mesh-tailoring strategy. Adv. Mater. 36, 2313495 (2024).

Guan, W. et al. Supramolecular adhesives with extended tolerance to extreme conditions via water-modulated noncovalent interactions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202303506 (2023).

Wang, Z. et al. A bioinspired adhesive-integrated-agent strategy for constructing robust gas-sensing arrays. Adv. Mater. 33, 2106067 (2021).

Hu, S. et al. A mechanically reinforced super bone glue makes a leap in hard tissue strong adhesion and augmented bone regeneration. Adv. Sci. 10, 2206450 (2023).

Han, X. et al. Noncontact microfluidics of highly viscous liquids for accurate self-splitting and pipetting. Adv. Mater. 36, 2402779 (2024).

Cinelli, M. A. et al. Phenyl ether- and aniline-containing 2-aminoquinolines as potent and selective inhibitors of neuronal nitric oxide synthase. J. Med. Chem. 58, 8694–8712 (2015).

Acknowledgements

We thank L. Chen from the Chemistry Instrumentation Center of Zhejiang University for technical support. This work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (grant no. 2021YFA0910100 to F.H.), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant nos. 22035006, 22350007 and 22320102001 to F.H., 22205200 and 22475188 to G.L., 22405238 to X.Y., 52373081 to W. You and 52333001 to W. Yu), the Zhejiang Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. LZ24B040001 to G.L.), the Starry Night Science Fund of Zhejiang University Shanghai Institute for Advanced Study (grant no. SN-ZJU-SIAS-006 to F.H.), the Leading Innovation Team grant from the Department of Science and Technology of Zhejiang Province (grant no. 2022R01005 to F.H.) and the ‘Pioneer’ R&D Program of Zhejiang Province (grant no. 2023C01087 to F.H.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

F.H. and G.L. formulated and supervised the project. Z.H. performed the synthesis of entangled nodes and the preparation of the polymer networks. W. You and W. Yu performed the rheological characterization of the polymeric networks. T.S. performed the single-crystal X-ray crystal structural analysis of the entangled node. C.Z., D.X. and Q.S. performed bonding tests of the polymer networks. Z.H., L.C., X.Y. and H.M. analysed the data. Z.H., L.C., G.L. and F.H. wrote the manuscript. All authors contributed to the data analysis, discussion and manuscript revision.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Materials thanks the anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figs. 1–101, discussion and Tables 1–7.

Supplementary Video 1

Video of the dumbbell lifting experiment.

Supplementary Video 2

Video of the vehicle traction test.

Supplementary Data 1

Crystallographic data for the node.

Source data

Source Data Fig. 2

Source data for Fig. 2.

Source Data Fig. 3

Source data for Fig. 3.

Source Data Fig. 4

Source data for Fig. 4.

Source Data Fig. 5

Source data for Fig. 5.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

He, Z., Chen, L., You, W. et al. Weaving-inspired asymmetric entangled nodes in multi-component polymer networks. Nat. Mater. 25, 107–116 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41563-025-02400-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41563-025-02400-w

This article is cited by

-

Bound to entangle

Nature Materials (2026)