Abstract

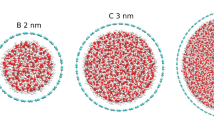

Nanoconfined water exhibits many abnormal properties compared with bulk water. However, the origin of those anomalies remains controversial due to the lack of experimental access to the molecular-level details of the hydrogen-bonding network of water within a nanocavity. Here we address this issue by combining scanning probe microscopy with nitrogen-vacancy-centre-based quantum sensing. Such a technique allows us to characterize both dynamics and structure of water confined between a hexagonal boron nitride flake and a hydrophilic diamond surface by nanoscale nuclear magnetic resonance. We observe a liquid–solid phase transition of nanoconfined water at ambient temperature with an onset confinement size of ~1.6 nm, below which the water diffusion is considerably suppressed and the hydrogen-bonding network of water becomes structurally ordered. The complete crystallization is observed below a confinement size of ~1 nm. The liquid–solid transition is further confirmed by molecular dynamics simulation. These findings shed new light on the phase transition of nanoconfined water and may form a unified picture for understanding water anomalies at the nanoscale.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$32.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $21.58 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

The relevant data supporting the findings of this study are available via Zenodo (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17555910)82. All other data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the Article or Supplementary Information. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

The code used in this study for the NMR simulations is available via Zenodo (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17555910)82.

References

Liou, Y. C., Tocilj, A., Davies, P. L. & Jia, Z. C. Mimicry of ice structure by surface hydroxyls and water of a β-helix antifreeze protein. Nature 406, 322–324 (2000).

Sui, H. X., Han, B. G., Lee, J. K., Walian, P. & Jap, B. K. Structural basis of water-specific transport through the AQP1 water channel. Nature 414, 872–878 (2001).

Joshi, R. K. et al. Precise and ultrafast molecular sieving through graphene oxide membranes. Science 343, 752–754 (2014).

Surwade, S. P. et al. Water desalination using nanoporous single-layer graphene. Nat. Nanotechnol. 10, 459–464 (2015).

Hanikel, N., Prévot, M. S. & Yaghi, O. M. MOF water harvesters. Nat. Nanotechnol. 15, 348–355 (2020).

Logan, B. E. & Elimelech, M. Membrane-based processes for sustainable power generation using water. Nature 488, 313–319 (2012).

Holt, J. K. et al. Fast mass transport through sub-2-nanometer carbon nanotubes. Science 312, 1034–1037 (2006).

Radha, B. et al. Molecular transport through capillaries made with atomic-scale precision. Nature 538, 222–225 (2016).

Fumagalli, L. et al. Anomalously low dielectric constant of confined water. Science 360, 1339–1342 (2018).

Chin, H. T. et al. Ferroelectric 2D ice under graphene confinement. Nat. Commun. 12, 6291 (2021).

Khan, S. H., Matei, G., Patil, S. & Hoffmann, P. M. Dynamic solidification in nanoconfined water films. Phys. Rev. Lett. 105, 106101 (2010).

Zangi, R. & Mark, A. E. Monolayer ice. Phys. Rev. Lett. 91, 025502 (2003).

Giovambattista, N., Rossky, P. J. & Debenedetti, P. G. Phase transitions induced by nanoconfinement in liquid water. Phys. Rev. Lett. 102, 050603 (2009).

Falk, K., Sedlmeier, F., Joly, L., Netz, R. R. & Bocquet, L. Molecular origin of fast water transport in carbon nanotube membranes: superlubricity versus curvature dependent friction. Nano Lett. 10, 4067–4073 (2010).

Han, S. H., Choi, M. Y., Kumar, P. & Stanley, H. E. Phase transitions in confined water nanofilms. Nat. Phys. 6, 685–689 (2010).

Kastelowitz, N. & Molinero, V. Ice-liquid oscillations in nanoconfined water. ACS Nano 12, 8234–8239 (2018).

Kapil, V. et al. The first-principles phase diagram of monolayer nanoconfined water. Nature 609, 512–516 (2022).

Jiang, J. et al. Rich proton dynamics and phase behaviours of nanoconfined ices. Nat. Phys. 20, 456–464 (2024).

Ma, R. Z. et al. Atomic imaging of the edge structure and growth of a two-dimensional hexagonal ice. Nature 577, 60–63 (2020).

Hong, J. N. et al. Imaging surface structure and premelting of ice Ih with atomic resolution. Nature 630, 375–380 (2024).

Algara-Siller, G. et al. Square ice in graphene nanocapillaries. Nature 519, 443–445 (2015).

Grünberg, B. et al. Hydrogen bonding of water confined in mesoporous silica MCM-41 and SBA-15 studied by H solid-state NMR. Chemistry 10, 5689–5696 (2004).

Ishizaki, T., Maruyama, M., Furukawa, Y. & Dash, J. G. Premelting of ice in porous silica glass. J. Cryst. Growth 163, 455–460 (1996).

Sovago, M. et al. Vibrational response of hydrogen-bonded interfacial water is dominated by intramolecular coupling. Phys. Rev. Lett. 100, 173901 (2008).

Wang, Y. H. et al. In situ Raman spectroscopy reveals the structure and dissociation of interfacial water. Nature 600, 81–85 (2021).

Xu, Y., Ma, Y. B., Gu, F., Yang, S. S. & Tian, C. S. Structure evolution at the gate-tunable suspended graphene-water interface. Nature 621, 506–510 (2023).

Alabarse, F. G. et al. Freezing of water confined at the nanoscale. Phys. Rev. Lett. 109, 035701 (2012).

Staudacher, T. et al. Nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy on a (5-nanometer)3 sample volume. Science 339, 561–563 (2013).

Schmitt, S. et al. Submillihertz magnetic spectroscopy performed with a nanoscale quantum sensor. Science 356, 832–837 (2017).

Degen, C. L., Reinhard, F. & Cappellaro, P. Quantum sensing. Rev. Mod. Phys. 89, 035002 (2017).

Du, J. F., Shi, F. Z., Kong, X., Jelezko, F. & Wrachtrup, J. Single-molecule scale magnetic resonance spectroscopy using quantum diamond sensors. Rev. Mod. Phys. 96, 025001 (2024).

Zheng, W. T. et al. Coherence enhancement of solid-state qubits by local manipulation of the electron spin bath. Nat. Phys. 18, 1317–1323 (2022).

DeVience, S. J. et al. Nanoscale NMR spectroscopy and imaging of multiple nuclear species. Nat. Nanotechnol. 10, 129–136 (2015).

Aslam, N. et al. Nanoscale nuclear magnetic resonance with chemical resolution. Science 357, 67–71 (2017).

Bian, K. et al. Nanoscale electric-field imaging based on a quantum sensor and its charge-state control under ambient condition. Nat. Commun. 12, 2457 (2021).

Bian, K. et al. A scanning probe microscope compatible with quantum sensing at ambient conditions. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 95, 053707 (2024).

Zhu, Y. B., Wang, F. C., Bai, J. I., Zeng, X. C. & Wu, H. A. Compression limit of two-dimensional water constrained in graphene nanocapillaries. ACS Nano 9, 12197–12204 (2015).

Leng, Y. S. & Cummings, P. T. Hydration structure of water confined between mica surfaces. J. Chem. Phys. 124, 074711 (2006).

Lane, J. M. D., Chandross, M., Stevens, M. J. & Grest, G. S. Water in nanoconfinement between hydrophilic self-assembled monolayers. Langmuir 24, 5209–5212 (2008).

Kumar, H., Dasgupta, C. & Maiti, P. K. Phase transition in monolayer water confined in Janus nanopore. Langmuir 34, 12199–12205 (2018).

Staudacher, T. et al. Probing molecular dynamics at the nanoscale via an individual paramagnetic centre. Nat. Commun. 6, 8527 (2015).

Yang, Z. P. et al. Detection of magnetic dipolar coupling of water molecules at the nanoscale using quantum magnetometry. Phys. Rev. B 97, 205438 (2018).

Baldwin, C. G., Downes, J. E., McMahon, C. J., Bradac, C. & Mildren, R. P. Nanostructuring and oxidation of diamond by two-photon ultraviolet surface excitation: an XPS and NEXAFS study. Phys. Rev. B 89, 195422 (2014).

Sangtawesin, S. et al. Origins of diamond surface noise probed by correlating single-spin measurements with surface spectroscopy. Phys. Rev. X. 9, 031052 (2019).

Laage, D., Elsaesser, T. & Hynes, J. T. Water dynamics in the hydration shells of biomolecules. Chem. Rev. 117, 10694–10725 (2017).

Xu, K., Cao, P. G. & Heath, J. R. Graphene visualizes the first water adlayers on mica at ambient conditions. Science 329, 1188–1191 (2010).

Shin, D., Hwang, J. & Jhe, W. Ice-VII-like molecular structure of ambient water nanomeniscus. Nat. Commun. 10, 286 (2019).

Martelli, F., Calero, C. & Franzese, G. Redefining the concept of hydration water near soft interfaces. Biointerphases 16, 020801 (2021).

Wu, D. et al. Probing structural superlubricity of two-dimensional water transport with atomic resolution. Science 384, 1254–1259 (2024).

Maletinsky, P. et al. A robust scanning diamond sensor for nanoscale imaging with single nitrogen-vacancy centres. Nat. Nanotechnol. 7, 320–324 (2012).

Boss, J. M., Cujia, K. S., Zopes, J. & Degen, C. L. Quantum sensing with arbitrary frequency resolution. Science 356, 837–840 (2017).

Schwartz, I. et al. Robust optical polarization of nuclear spin baths using Hamiltonian engineering of nitrogen-vacancy center quantum dynamics. Sci. Adv. 4, eaat8978 (2018).

Zhao, N. et al. Sensing single remote nuclear spins. Nat. Nanotechnol. 7, 657–662 (2012).

Bocquet, L. Nanofluidics coming of age. Nat. Mater. 19, 254–256 (2020).

Casola, F., van der Sar, T. & Yacoby, A. Probing condensed matter physics with magnetometry based on nitrogen-vacancy centres in diamond. Nat. Rev. Mater. 3, 17088 (2018).

Giessibl, F. J. The qPlus sensor, a powerful core for the atomic force microscope. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 90, 011101 (2019).

de Oliveira, F. F. et al. Tailoring spin defects in diamond by lattice charging. Nat. Commun. 8, 15409 (2017).

Rugar, D. et al. Proton magnetic resonance imaging using a nitrogen-vacancy spin sensor. Nat. Nanotechnol. 10, 120–124 (2015).

Lovchinsky, I. et al. Magnetic resonance spectroscopy of an atomically thin material using a single-spin qubit. Science 355, 503–507 (2017).

Wastl, D. S., Weymouth, A. J. & Giessibl, F. J. Optimizing atomic resolution of force microscopy in ambient conditions. Phys. Rev. B 87, 245415 (2013).

Glenn, D. R. et al. High-resolution magnetic resonance spectroscopy using a solid-state spin sensor. Nature 555, 351–354 (2018).

Shannon, C. E. Communication in the presence of noise. Proc. Inst. Radio Eng. 37, 10–21 (1949).

Lu, S. H. et al. Ground-state structure of oxidized diamond (100) surface: an electronically nearly surface-free reconstruction. Carbon 159, 9–15 (2020).

Zamborlini, G. et al. Nanobubbles at GPa pressure under graphene. Nano Lett. 15, 6162–6169 (2015).

Khestanova, E., Guinea, F., Fumagalli, L., Geim, A. K. & Grigorieva, I. V. Universal shape and pressure inside bubbles appearing in van der Waals heterostructures. Nat. Commun. 7, 12587 (2016).

Vasu, K. S. et al. Van der Waals pressure and its effect on trapped interlayer molecules. Nat. Commun. 7, 12168 (2016).

Lin, S. T., Blanco, M. & Goddard III, W. The two-phase model for calculating thermodynamic properties of liquids from molecular dynamics: validation for the phase diagram of Lennard-Jones fluids. J. Chem. Phys. 119, 11792–11805 (2003).

Jorgensen, W. L., Maxwell, D. S. & TiradoRives, J. Development and testing of the OPLS all-atom force field on conformational energetics and properties of organic liquids. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 118, 11225–11236 (1996).

Abascal, J. L. F., Sanz, E., Fernández, R. G. & Vega, C. A potential model for the study of ices and amorphous water: TIP4P/Ice. J. Chem. Phys. 122, 234511 (2005).

Conde, M. M., Rovere, M. & Gallo, P. High precision determination of the melting points of water TIP4P/2005 and water TIP4P/Ice models by the direct coexistence technique. J. Chem. Phys. 147, 244506 (2017).

Johnston, J. C., Kastelowitz, N. & Molinero, V. Liquid to quasicrystal transition in bilayer water. J. Chem. Phys. 133, 154516 (2010).

Babin, V., Leforestier, C. & Paesani, F. Development of a ‘first principles’ water potential with flexible monomers: dimer potential energy surface, VRT spectrum, and second virial coefficient. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 9, 5395–5403 (2013).

Babin, V., Medders, G. R. & Paesani, F. Development of a ‘first principles’ water potential with flexible monomers. II: trimer potential energy surface, third virial coefficient, and small clusters. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 10, 1599–1607 (2014).

Medders, G. R., Babin, V. & Paesani, F. Development of a ‘first principles’ water potential with flexible monomers. III. Liquid phase properties. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 10, 2906–2910 (2014).

Thompson, A. P. et al. LAMMPS—a flexible simulation tool for particle-based materials modeling at the atomic, meso, and continuum scales. Comput. Phys. Commun. 271, 108171 (2022).

Lee, K., Murray, ÉD., Kong, L. Z., Lundqvist, B. I. & Langreth, D. C. Higher-accuracy van der Waals density functional. Phys. Rev. B 82, 081101(R) (2010).

Brandenburg, J. G., Zen, A., Alfè, D. & Michaelides, A. Interaction between water and carbon nanostructures: how good are current density functional approximations?. J. Chem. Phys. 151, 164702 (2019).

Goedecker, S., Teter, M. & Hutter, J. Separable dual-space Gaussian pseudopotentials. Phys. Rev. B 54, 1703–1710 (1996).

Kühne, T. D. et al. CP2K: an electronic structure and molecular dynamics software package—quickstep: efficient and accurate electronic structure calculations. J. Chem. Phys. 152, 194103 (2020).

Calero, C. & Franzese, G. Water under extreme confinement in graphene: oscillatory dynamics, structure, and hydration pressure explained as a function of the confinement width. J. Mol. Liq. 317, 114027 (2020).

Leoni, F., Calero, C. & Franzese, G. Nanoconfined fluids: uniqueness of water compared to other liquids. ACS Nano 15, 19864–19876 (2021).

Zheng, W. et al. Experimental observation of liquid-solid transition of nanoconfined water at ambient temperature. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17555910 (2025).

Acknowledgements

We thank L. Yang and C. Yu from Peking University (PKU) for their help with the 2D material transfer and fabrications, and N. Zhao from Beijing Computational Science Research Center (CSRC) for meaningful guidance and discussions on the NMR simulations. This work was supported by the National Key R&D Program under grant number 2021YFA1400500; the Program under grant number 2023ZD0301300; the National Natural Science Foundation of China under grant numbers 11888101, 21725302, 12474160, U22A20260 and 12250001; the Strategic Priority Research Program of the Chinese Academy of Sciences under grant number XDB28000000; and the Beijing Municipal Science & Technology Commission under grant number Z231100006623009. W.Z. acknowledges the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation under grant number 2022M710235. Y.J. acknowledges the New Cornerstone Science Foundation through the New Cornerstone Investigator Program and the XPLORER PRIZE, and the Beijing Outstanding Young Scientist Program under grant number JWZQ20240101002. X.C.Z. acknowledges support from the Hong Kong Global STEM Professorship Scheme and the Research Grants Council of Hong Kong (GRF grant numbers 11204123 and 11302225). J.J. acknowledges funding support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant number 22303072). R.S., A.D. and J.W. acknowledge the BMBF via Clusters4Future: QSens and the DFG under grant numbers FOR 2724, GRK 2642 and WR 28/34-1.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.J., K.B. and E.-G.W. supervised the project. K.B. and Y.J. designed the experiment. R.S. and A.D. grew the diamond chips and fabricated the shallow NVs. S.Z. and W.Z. transferred the hBN flakes and fabricated the hBN–diamond structure. W.Z. and S.Z. performed the experiments and data acquisition. W.Z., S.Z., J.J., K.B., Y.H., J.W., X.C.Z., Y.J. and E.-G.W. performed the experimental data analysis and interpretation. J.J. and X.C.Z. performed the MD simulations. W.Z., S.Z., J.J. and K.B. performed the NMR simulations. W.Z., K.B., S.Z., J.J., X.C.Z., Y.J. and E.-G.W. wrote the manuscript with input from all other authors. All authors commented on the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Materials thanks Giancarlo Franzese, Francesco Paesani and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Extended Data Fig. 1 Determine the thickness of the intrinsic water layer on the diamond surface.

(a) Topographic image of diamond surface without the hBN flake, corresponding to the open system. The position of the NV center was determined by the procedures described in Supplementary Fig. 1, denoted as an orange dashed circle with the nearby reference protrusion being marked by an arrow. (b) Topographic image of the same area with the hBN flake and without confined water molecules, which was confirmed by the nanoscale-NMR measurement. (c) Z-profile was measured along the dashed line in (a) (black) and in (b) (red). The position of the NV center was estimated with an uncertainty denoted by the shades. The measured height difference of the two profiles indicates the thickness of the intrinsic water layer on the diamond surface: dwater = 2.7 ± 0.2 nm. Scale bar: 250 nm.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Nanoscale-NMR spectroscopies showing beating features under the strong confinement measured by two different NVs.

(a) Left panel: correlation spectroscopy at a confinement size of 0.7 ± 0.3 nm measured by an NV with depth of 4.39 ± 0.49 nm. By using a sum of cosine functions with multiple frequencies and an exponentially decayed envelope \(S\left(\widetilde{\tau }\right)={e}^{-\widetilde{\tau }/{T}_{{\rm{corr}}}}{\sum }_{i}{S}_{i}\cos \left({2\pi f}_{i}\widetilde{{\rm{\tau }}}+{\varphi }_{i}\right)\), the signal was fitted with a time constant of Tcorr = 183.7 ± 29.5 µs. Right panel: the corresponding power spectrum showing a multi-peak feature. (b) Left panel: correlation spectroscopy at a confinement size of 1.5 ± 0.4 nm measured by an NV with depth of 5.13 ± 0.65 nm. The signal was fitted with a time constant of Tcorr = 224.3 ± 45.1 µs. Right panel: the corresponding power spectrum showing two peaks.

Extended Data Fig. 3 Influence of surface functionalization on the diffusivity of nanoconfined water.

(a) The hydroxylated (100) surface with carbonyl(-C = O), ether(C-O-C), and hydroxyl(-OH) functional groups, and (b) the methoxy-acetone oxidized diamond (100) surface with carbonyl(-C = O) and ether(C-O-C) functional groups adopted for classical MD simulation. Red, white, and gray balls represent oxygen, hydrogen, and carbon atoms, respectively. (c) The calculated diffusion coefficients of the whole water layer in three different confinement systems from MD simulation: (1) Water confined between a hydroxylated hydrophilic diamond surface and a hydrophobic hBN surface (gray), (2) water confined between a methoxy-acetone oxidized hydrophilic diamond surface and a hydrophobic hBN surface (red), and (3) water confined between two hydrophobic hBN surfaces (blue). Dt are presented as mean values ± standard deviations, derived from 3 simulations.

Extended Data Fig. 4 MD simulation of the rotational coefficients of the whole water layer.

Rotational coefficients (Dr) were calculated through the statistical trajectories of water molecules, for dconfine ranging from 1 nm to 6 nm, where they exhibited a large suppression at dconfine < 2 nm. Dr are presented as mean values ± standard deviations, derived from 3 simulations.

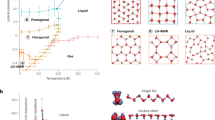

Extended Data Fig. 5 Calculation of the bond-order parameter.

Calculated local q6 Steinhardt parameters of the confined water layer with dconfine ranging from 0.6 nm to 6 nm by using the TIP4P/Ice model. q6 bond-order parameter quantifies the six-fold symmetry of the hydrogen bond structures. The results show increased ordering with decreasing confinement size, with two transition points of slope change (marked by arrows) at approximately 2.1 nm and 1.2 nm, respectively. The increase in q6 at ~2.1 nm indicates the onset of the liquid-solid transition, while the sharp increase in q6 at ~1.2 nm indicates the rapid crystallization.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Texts 1–8, Table 1, Figs. 1–11 and refs. 1–21.

Supplementary Data 1

Raw data for Supplementary Fig. 1.

Supplementary Data 2

Raw data for Supplementary Fig. 2c,d.

Supplementary Data 3

Raw data for Supplementary Fig. 3b.

Supplementary Data 4

Raw data for Supplementary Fig. 4b.

Supplementary Data 5

Raw data for Supplementary Fig. 5.

Supplementary Data 6

Raw data for Supplementary Fig. 8.

Supplementary Data 7

Raw data for Supplementary Fig. 10d,e.

Supplementary Data 8

Raw data for Supplementary Fig. 11.

Source data

Source Data Fig. 1

Raw data for Figs. 1d–g.

Source Data Fig. 2

Raw data for Fig. 2a–c.

Source Data Fig. 3

Raw data for Fig. 3a,b.

Source Data Fig. 4

Raw data and code for Fig. 4d.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 1

Raw data for Extended Data Fig. 1a–c.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 2

Raw data for Extended Data Fig. 2.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 3

Raw data for Extended Data Fig. 3.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 4

Raw data for Extended Data Fig. 4.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 5

Raw data for Extended Data Fig. 5.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Zheng, W., Zhang, S., Jiang, J. et al. Experimental observation of liquid–solid transition of nanoconfined water at ambient temperature. Nat. Mater. (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41563-025-02456-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41563-025-02456-8