Abstract

Among the candidates to replace Li-ion batteries, Li–S cells are an attractive option as their energy density is about five times higher (~2,600 Wh kg−1). The success of Li–S cells depends in large part on the utilization of metallic Li as anode material. Metallic lithium, however, is prone to grow parasitic dendrites and is highly reactive to several electrolytes; moreover, Li–S cells with metallic Li are also susceptible to polysulfides dissolution. Here, we show that ~10-nm-thick two-dimensional (2D) MoS2 can act as a protective layer for Li-metal anodes, greatly improving the performances of Li–S batteries. In particular, we observe stable Li electrodeposition and the suppression of dendrite nucleation sites. The deposition and dissolution process of a symmetric MoS2-coated Li-metal cell operates at a current density of 10 mA cm−2 with low voltage hysteresis and a threefold improvement in cycle life compared with using bare Li-metal. In a Li–S full-cell configuration, using the MoS2-coated Li as anode and a 3D carbon nanotube–sulfur cathode, we obtain a specific energy density of ~589 Wh kg−1 and a Coulombic efficiency of ~98% for over 1,200 cycles at 0.5 C. Our approach could lead to the realization of high energy density and safe Li-metal-based batteries.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

The rapidly growing demand for sustainable and clean energy applications, including electric vehicle and smart grid storage, has challenged the research community to develop battery systems beyond Li-ion, as this has reached the limits in terms of energy and power densities. Alternatives include lithium–air (Li–O2) and lithium–sulfur (Li–S) batteries. Lithium metal is known as a lightweight anode material, owing to its ability to store Li without the need for an intercalating and/or conducting scaffold1, 2. For this reason, Li-metal electrodes exhibit high theoretical specific capacity (~3,860 mAh g−1) and low redox potential (−3.04 V)3. They are therefore often regarded as the anodes of choice for the next-generation rechargeable Li-metal batteries, especially for Li–S battery systems.

Despite many advantages, Li–S batteries are plagued with practical issues that limit their applications: (1) the poor electronic conductivity of sulfur that retards electron transfer during the charge/discharge processes4; (2) the formation of intermediate polysulfides generated during cycling, which leads to the shuttle effect and increases the impedance of both electrodes5; (3) the intrinsic issues of Li-metal anodes, which are often associated with uncontrollable dendrite formation during repeated Li deposition and dissolution processes3; and (4) the formation of an unstable solid electrolyte interphase (SEI) layer between the electrolyte and Li metal due to inhomogeneous deposition of Li6. These issues lead to the reduction of Coulombic efficiency and the subsequent fast termination of battery life.

To tackle the issues regarding the sulfur cathode (1 and 2), various carbon-based materials, for example, porous carbon, carbon nanotubes (CNTs), graphene and fibrous carbon networks, have been shown to enhance the electrochemical properties of sulfur in Li–S batteries7,8,9,10. Recently, we reported that three-dimensional (3D) CNT composite structures can improve the electrical conductivity of the sulfur cathode while preventing polysulfides from shuttling during cycling11. Despite the progress made on the cathode of Li–S batteries, the issues associated with Li metal and its interactions with electrolytes (3 and 4) still remain a major concern, including battery safety. Therefore, it is crucial to resolve the issues with Li-metal anodes to realize the full potential of Li–S batteries.

Several techniques have been proposed to suppress Li dendrite growth and/or to enhance the stability of Li metal through: liquid electrolyte modification with additives (concentrated electrolyte12 or Cs ions13); use of Li+ conducting polymer or solid-state electrolytes14, 15; use of artificially induced SEI through self-assembled carbon spheres16; applications of thin layer of coatings such as a composite film or alumina (Al2O3) layer17, 18; and electrodeposition of Li into conducting frameworks (for example, graphene or graphene flakes)19, 20.

Studies behind liquid electrolyte modifications are aimed at controlling Li-metal plating to facilitate stable SEI layers. However, these SEI layers are still prone to getting damaged by the continuous Li-metal deposition and dissolution processes. Furthermore, the growth of Li dendrites (regardless of their geometries) still persists, inevitably leading to a low Coulombic efficiency21. Attempts to suppress Li dendrite growth with solid-state electrolytes have also been unsuccessful as their low ionic conductivity, large thickness and poor interfacial contact to Li metal cause large cell overpotential (that is, high cell impedance) during the charge/discharge process. Similar issues arise with polymer and ceramic-coated Li metal.

Although some coatings have shown promising results for Li–S batteries, they operate at relatively low current densities (<1 mA cm−2) because of the high impedance at the interface between the coating and the electrolyte, making them unsuitable for large-scale applications requiring higher current densities (>3 mA cm−2)12, 22. In addition, lithiated conducting frameworks showed remarkable results without encountering any impedance issues. However, these approaches did not make use of bulk Li-metal electrodes, and also did not achieve a cycle life and energy density of 1,000 cycles and 500 Wh kg−1, respectively—values paramount for practical application23. Evidently, an approach that addresses the above-mentioned drawbacks is crucial for the development of stable Li-metal anodes.

Here, we propose to passivate Li metal with atomic layers of two-dimensional molybdenum disulfide (2D MoS2) and create a protective barrier between the Li metal and electrolyte. Large amounts of Li atoms can intercalate into the atomically layered MoS2 structure to reduce the interfacial resistance and facilitate a consistent flow of Li+ into and out of bulk Li metal. Unlike other carbon-, composite-, or ceramic-based protective layers, the unique atomically layered structure and its phase-change characteristics (semiconductor to metallic trait) circumvent the issues of high impedance and/or poor interfacial-contact24, 25. Also, the enhanced conductivity of the MoS2 interlayer eliminates the preferential sites for Li dendrite nucleation (Supplementary Note 1). With the use of a MoS2 passivated Li-metal anode and a CNT–S composite cathode to encapsulate soluble polysulfides, it is possible to realize high-performing Li–S batteries. As demonstrated, the cells deliver a specific energy density of ~589 Wh kg−1, high cycling stability of over 1,200 cycles and an average Coulombic efficiency of ~98%.

Preparation and characterization of MoS2-coated electrodes

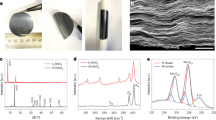

We developed a scalable method to coat 2D MoS2 on Li metal via sputtering (Fig. 1a). From the scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images (Fig. 1b,c), it is apparent that the MoS2 was uniformly deposited throughout the surface of Li metal. The cross-sectional image (Fig. 1b) and atomic force microscopy height measurement (Supplementary Fig. 1) show that the deposited layer of MoS2 is ~10 nm thick and adheres tightly to the surface of Li metal (Supplementary Fig. 2); in addition, the MoS2 layer exhibits uniformity over the entire Li-metal surface (Supplementary Fig. 3). It is important to optimize the film uniformity and low impedance of the MoS2 layer to maintain high ionic conductivity without increasing the overall cell impedance as well as inducing uneven local impedance. Thus, galvanostatic electroplating at a constant current density of 1 mA cm−2 was carried out for both bare (Supplementary Fig. 4) and MoS2-coated Li (Supplementary Fig. 5) to determine its optimal thickness. As observed during the lithiation process, the MoS2 layer underwent a morphological change from polycrystalline film to a flake-like morphology (Fig. 1c,d).

a, Schematics illustrating the fabrication method for a MoS2-coated Li anode via sputtering and subsequent lithiation. Left: direct MoS2 deposition to the surface of Li metal. Middle: lithiating the MoS2 layer through a symmetric cell configuration and cycling for 15 cycles (30 min charge/discharge per cycle) at 1 mA cm−2. Right: dismantling the symmetric cell to obtain the lithiated MoS2-coated Li electrode. b,c, Cross-section (b) and top view (c) SEM images of the as-deposited MoS2 on Li metal. The inset in c is a magnified view. (d) Top view SEM image of the lithiated MoS2 on Li-metal surface.

MoS2 is considered a polymorphic material; it is composed of monolayers of hexagonally packed sheets of Mo atoms covalently bonded to two hexagonal layers of S atoms24. Two primary structural polymorphs are octahedral (1T) and trigonal prismatic (2H). Each polymorph has its own coordinated structure that defines its electronic property: metallic for 1T-MoS2 and semiconducting for 2H-MoS2 (refs 25, 26).

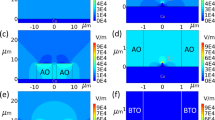

From density functional theory (DFT) results (Fig. 2a), it is evident that the structure of 2H-MoS2 is stable until the concentration of Li (number of intercalated Li per MoS2 formula unit) reaches 0.4. When Li concentration exceeds 0.4, the 1T-MoS2 structure becomes stable. In addition, the total volume of the MoS2 lattice structure is expected to expand at up to ~14% on lithiation, as illustrated schematically in Fig. 2b,c. Thus, the lithiation process outlined in Fig. 1 transforms the MoS2 layer into a metallic 1T phase.

a, Comparison of the relative stability change induced by Li intercalation. ET and EH indicate the energy of the T and H phase of MoS2, respectively, for a given Li concentration. V/V0 is the volume expansion ratio, where V0 is the volume of MoS2 before Li intercalation and V is the volume of MoS2 as a function of Li concentration. For lower Li concentration, the 2H phase is the stable phase of MoS2. When the number of Li per MoS2 exceeds 0.4, the 1T phase becomes stable. With Li intercalation, the total volume expands up to about 14%. b,c, Model structures of pristine 2H-MoS2 (b) and 1T Li–MoS2 (c). d, Nyquist plots of both bare and MoS2-coated cells after cycling at 1 mA cm−2 for 15 cycles. Zreal and –ZIm are the real and imaginary impedances of the cell, respectively. e, Raman spectra illustrating the peak profiles for both as-deposited and lithiated MoS2 layers. f, Mo 3d and S 2s XPS spectra of as-deposited and lithiated MoS2 layers on Li metal. g,h, HRTEM images of as-deposited (g) and lithiated (h) MoS2. The inset in g is the FFT pattern, suggesting a hexagonal arrangement of S and Mo elements for the MoS2 layer.

The electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) measurements shown in Fig. 2d illustrate the impedance for both lithiated MoS2-coated Li and bare Li symmetric cells. The high frequency range semi-circle is attributed to the film resistance from the SEI layer formed on bare and MoS2-coated Li surface, while the low frequency range semi-circle indicates charge transfer resistance between the SEI film and Li27. Although both curves exhibit comparable film and charge-transfer resistance values, the slope in the low frequency range for the MoS2-coated Li electrode is slightly higher than that of the bare Li. Thus, it is suggested that Li diffusion through the MoS2 layer exhibits comparable characteristics to that of the SEI layer on bare Li metal.

The two representative Raman modes in the 2H-MoS2 are E12g (in-plane) and A1g (out-of-plane) (Fig. 2e). The in-plane vibration mode is related to opposing vibrations of the Mo and S atoms with opposite directions in parallel with each other, whereas the out-of-plane mode occurs due to vibrations of the two S atoms in the opposite directions28. In previous studies on Li-ion batteries, the 1T-MoS2 was discovered after lithiation where Li+ sheet and electronic conductivities were estimated around 2.8 × 1014 cm−2 and 2.10 × 10−6 S cm−1, respectively29,30,31. Before cycling, the representative Raman modes of E12g and A1g are 381.4 cm−1 and 416.9 cm−1, respectively. Also, the distance between two modes (~35 cm−1) suggests ~10 layers of 2H-MoS2 (refs 29, 32). For the lithiated MoS2 layer, the two Raman modes with respect to 2H-MoS2 are blueshifted and a new mode of J3 (339.4 cm−1) appears without any change in the distance between the modes. The new mode of J3 tends to split each zig-zag chain into two stripes with a slight out-of-plane component that is found in metallic 1T-MoS2 (ref. 33). Furthermore, the redshift of the X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) peak positions (Fig. 2f and Supplementary Fig. 6), support the phase transition of MoS2 structure from a semiconducting to metallic phase34.

The high-resolution transmission electron microscopy (HRTEM) image of the as-deposited MoS2 film reveals a lattice plane spacing of ~0.314 nm; the fast Fourier transform (FFT) pattern (Fig. 2g inset) shows that the layer retains some degree of crystal symmetry. The Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (https://icsd.fiz-karlsruhe.de/search/) states the Mo–Mo lattice spacing is ~3.16 Å; thus, it is assumed that the lattice spacing of the as-deposited MoS2 matches that of the 2H-MoS2. In Fig. 2h, a single lithiated MoS2 nanoflake (also observed in Fig. 1) reveals that the lattice spacing has increased to ~0.335 nm, which is very likely due to the distortion caused by the lithiation of MoS2 structure29,30,31. The size of each MoS2 nanoflake ranges from 200 to 500 nm; also, the basal face of each nanoflake shows a step-like morphology (Supplementary Fig. 7).

Cyclic response of MoS2-coated Li metal

We carried out galvanostatic cycling performance of bare and MoS2-coated Li to investigate the stability of Li deposition/dissolution for both types of Li electrode. As shown by the voltage profile in Fig. 3a, both cells initially exhibit similar overpotential behaviour (expanded views for initial cycles are shown in Supplementary Fig. 8). However, the similarity ends around the 120th cycle when there is a sudden increase in polarization for bare Li. Beyond this point, the overpotential for the bare Li symmetric cell gradually increases to the voltage limit of the test parameter. Such gradual increase in polarization is generally associated with the successive decomposition of electrolyte prompted by the excessive build-up of ‘dead’ Li on the surface of Li metal (as confirmed by the SEM images in Supplementary Fig. 9). The MoS2-coated Li, in contrast, maintains stable voltage polarization (~52 mV) for 300 cycles.

a, Constant current charge/discharge voltage profiles for bare Li metal and MoS2-coated Li symmetric cells cycled at a current density of 10 mA cm−2. The inset shows the magnified voltage profile for the MoS2-coated Li symmetric cell. Galvanostatic tests at 1 and 3 mA cm–2 can be found in Supplementary Fig. 19. b,c, Nyquist plots of both cells after 15 cycles (b) and the end of charging/discharging test (c; 240 cycles for bare Li; 300 cycles for MoS2-coated Li). The inset in c is the magnified Nyquist plot for the MoS2-coated Li symmetric cell. d, SEM images showing the surface morphological changes between bare and MoS2-coated Li before and after the cycling test at 10 mA cm−2. The insets are the corresponding digital images of the electrodes. From the digital images of the electrodes acquired from the disassembled cells, the surface of the bare Li electrode clearly shows some signs of Li depletion as well as a porous layer. The surface of the MoS2-coated Li, in contrast, shows minimal signs of damage with no dendrite formation. The SEM and the digital images for both MoS2-coated and bare Li were taken after plating at the end of cycling test. e, Cross-section SEM image of the MoS2-coated Li metal after 300 h of cycling and the subsequent EDS elemental mapping of Mo and S outlined by the dashed yellow box. The intensity maps confirm that the chemical make-up of the layered region on top of Li metal is MoS2.

Initially (right after lithiation), both cells display comparable impedance characteristics (Fig. 3b). However, the resistance of the bare Li cell increases noticeably as the cell fails; in contrast, the resistance of the MoS2-coated Li cell reduces slightly after the cycling test (Fig. 3c). These findings support the phase transition of MoS2 from 2H to 1T, which reduces the interfacial resistance; that is, the electronic conductivity of the MoS2 interlayer is improved and maintained to facilitate long-term cycling stability.

In an ex-situ SEM analysis before and after cycling (Fig. 3d), the image of the cycled bare Li electrode (after plating at 240th cycle) shows a rough and porous layer of Li covering the entire surface of the electrode. Such observation supports the notion of increased voltage polarity (Fig. 3a) and impedance (Fig. 3c) for the bare Li electrode. In contrast, the image of the MoS2-coated Li electrode (after plating at 300th cycle) shows a rather smooth and unchanged texture even after 300 cycles of severe Li deposition/dissolution. This is supported by the cross-sectional SEM analysis of the MoS2-coated Li electrode after cycling (Fig. 3e). It is evident that the MoS2 layer establishes a strong interfacial bonding to the surface of Li metal with no delamination or signs of localized dendrite formation observed.

Also, energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) mapping (Fig. 3e) shows that the surface of the electrode is indeed a uniform MoS2 layer that has maintained structural stability with negligible expansion. It is therefore concluded that the lithiated MoS2 layer remains intact even after 300 cycles of high current density while also enabling stable Li deposition/dissolution.

The extent of Li removal during the charging cycles is considerably less than that for MoS2-coated Cu in half cells (Supplementary Fig. 10). The cell ultimately failed at the 75th cycle with a Coulombic efficiency less than 20% for the plain Cu. The charging behaviour for the MoS2-coated Cu, in contrast, was highly stable for up to 100 cycles and the Coulombic efficiency was maintained at ~90%. The addition of LiNO3 as an electrolyte additive stabilizes the SEI formation between the MoS2 layer and the electrolyte; thus, the overall Coulombic efficiency improves noticeably and stabilizes at ~99% (Supplementary Fig. 11).

Electrochemical testing

To test the applicability of symmetric, half-cell results, we paired the MoS2-coated Li anodes with our 3D CNT–S composites as cathodes11. A typical cyclic voltammetry for the full cell (Li–MoS2/CNT–S) outlines the first five cycles of the basic kinetics of Li+ involved in cathodic reduction and anodic oxidation (Fig. 4a). The well-defined reduction peaks observed at ~2.18 and ~1.9 V are associated with a reduction of elemental sulfur to long-chain lithium polysulfides (Li2S n , 4 ≤ n ≤ 8); subsequently, further reduction takes place that results in short-chain lithium polysulfides (Li2S2/Li2S). The reduction peaks are lower than the peaks found in other studies (2.3 and 2.1 V) 9,11. However, the shifts are due to a higher amount of pure sulfur used in this full-cell test, which triggers the sluggish kinetics of a solid–solid equilibrium reaction between the insoluble discharge products (Li2S2 and Li2S). Indeed, the system has an additional MoS2 interface layer, which contributes to the shift in polarization. Similarly, the oxidation proceeds through a two-step reaction: the conversion of Li2S2/Li2S to Li2S n (n > 2) occurring at ~2.43 V and the final formation of elemental sulfur with the oxidation peak taking place at ~2.5 V. These reduction and oxidation peaks are consistent with the reported carbon-based sulfur cathodes for Li–S batteries8,35. There is no significant variation in the cathodic and anodic currents from first to fifth cycles of cyclic voltammetry, which indicates high electrochemical stability of the cell9.

a, Cyclic voltammetry of the Li–MoS2/CNT–S cell within the voltage window of 1.5–3.0 V for the initial cycles. b, Rate capabilities of the Li–MoS2/CNT–S cell with a sulfur content of 33 wt% in the 3D CNT–S cathode tested at 0.1, 0.5, 1.0 and 2.0 C. c, The GCD profiles of the corresponding Li–MoS2/CNT–S cell for up to 1,200 cycles at 0.5 C. d, Calculated Ragone plot (energy versus power density) based on the electrochemical data presented in c with respect to the mass of the whole cathode (sulfur composite, carbon black, binder, aluminium current collector, and so on). The specific energy and power are compared with other references. e, Long-term cycling performance of Li–S battery with the 3D CNT–S cathode (~33 wt% S content) and the MoS2-coated Li anode measured at 0.5 C for 1,200 cycles. The average specific capacity decay is 0.013% per cycle and the Coulombic efficiency at 1,200th cycle is around 98%. The schematic inset illustrates the basic kinetics of Li+ between two electrodes during cycling.

Although, the specific capacity of the full cell decreases with increasing current rates (0.1 to 2 C rate), the cell maintains stable cycling (Fig. 4b). As the cell is cycled from lower to higher C rates, it maintains a capacity of 997 mAh g−1 at 0.5 C with a specific capacity retention of 81% even after 50 cycles. The galvanostatic charge/discharge (GCD) profiles are shown in Supplementary Fig. 12a. Indeed, the potential differences between the charge and discharge voltage plateaus increases with C rate, which is expected because the higher current density gives less time to convert sulfur to polysulfides efficiently and vice versa36.

The cycling performance of the bare Li (Li/CNT–S) and the Li–MoS2/CNT–S full cells at 0.1 C are compared in Supplementary Fig. 13a. The Li/CNT–S cell shows a continuous decrease in specific discharge capacity at up to 150 cycles; the test had to be terminated as the capacity decreased exponentially beyond this point. In contrast, the Li–MoS2/CNT–S cell exhibited stable cycling for over 300 cycles with a specific capacity retention of 96%. The GCD profiles for both cells are illustrated in Supplementary Fig. 13b,c. Indeed, we have achieved superior electrochemical performance of the Li–MoS2/CNT–S cell than recently reported studies10, 37.

For a long-term cycling test, the Li–MoS2/CNT–S cell was tested at 0.5 C for over 1,200 cycles; the GCD profiles for different cycles are illustrated in Fig. 4c. This cell exhibited a reversible specific capacity of 1,105 mAh g−1 at 0.5 C for the first cycle. The two plateaus in the discharge profile are observed at ~2.1 V and ~1.9 V; thus, the corresponding charge plateaus for the first cycle are consistent with those of cathodic and anodic peaks in cyclic voltammetry (Fig. 4a).

The stable electrochemical performance of the Li–MoS2/CNT–S is attributed to the fact that the 3D interconnected CNTs on the cathode side provide efficient electron and ion channels for effective sulfur utilization as well as prevention of Li dendrite growths on the anode side (Supplementary Note 2). Moreover, the surface morphology of the MoS2-coated Li anode after 1,200 cycles (Supplementary Fig. 14) is quite similar to the morphology from the symmetric cell test.

Based on the electrochemical data presented in Fig. 4c, the specific energy and power densities of the Li–MoS2/CNT–S cell measure 589 Wh kg−1 and 295 W kg−1 (equations (1) and (2) in Methods), respectively, after 1,200 cycles. From the Ragone plot (Fig. 4d), these values are generally higher than those previously reported38,39,40,41. Figure 4e presents the cycling life of the Li–MoS2/CNT–S cell measured at 0.5 C, delivering a specific capacity (with respect to the mass of sulfur) of ~940 mAh g−1 after 1,200 cycles and a capacity retention of 84%. This corresponds to an average capacity decay of 0.013% per cycle with a Coulombic efficiency of ~98%. In addition, the cell with higher sulfur content (~64 wt%) delivered a specific capacity of ~600 mAh g−1 for up to the 1,200th cycle (Supplementary Fig. 15). Also, the cell using the reduced amount of electrolyte (Supplementary Fig. 16) displayed results comparable to the standard amount.

Mechanistic study on Li diffusion in MoS2

We investigated the Li+ migration within the layered and the monolayer MoS2, for both low and high Li concentrations, using the DFT model; the simulation for the monolayer MoS2 can be represented as Li+ migration through the surface (Fig. 5). The surface/bulk migration simulations were more focused on the T phase as the experiments support the structural phase transition from the 2H to 1T phase after lithiation. In addition, the experimental data show that the nanoflakes are formed (Fig. 1d) during the initial lithiation cycles; thus, the space for Li diffusion is formed at the surface of MoS2 flakes as well as within the interlayer of MoS2 by the flow of Li+ under an externally applied electric field (Supplementary Fig. 17).

a, Li vacancy diffusion path in monolayer MoS2 in the T phase. Mo, S and Li atoms are represented by purple, yellow and green spheres, respectively. The migrating Li atom is represented by a red sphere. In this case, the migration occurs between two Mo top sites where a Li atom passes through a hollow site (see Supplementary Note 3 for further description). b, In-plane Li/Li vacancy migration energy in monolayer MoS2 for the T phase.

The bulk migration energy barriers for high and low Li concentrations are 0.73 eV and 0.59 eV, respectively; in the surface migration case, the energy barriers are greatly reduced to 0.42 eV and 0.16 eV (Fig. 5b). Although the underestimation of interlayer spacing can result in increased energy barriers for the bulk case, the results are still qualitatively true (Supplementary Tables 1 and 2). The lower surface migration energy barrier is in agreement with the experimental observation where the polytype MoS2 stacks are transformed after a few cycles of lithiation. Moreover, considering the H to T phase transition and the large Li binding energy (~3 eV), the Li diffusion will be dominated by Li migration on the surface of T-MoS2 with a much smaller energy barrier (0.155 eV) to overcome. Therefore, the surface migration path accelerates the diffusion of Li+ to suppress Li dendrite growth.

Conclusion

We have demonstrated a method of passivating a Li anode with atomic 2D layers of MoS2 directly coated and lithiated onto the surface of Li metal. The MoS2 layer exhibits tight adhesion to the surface of Li metal and facilitates uniform flow of Li+ into and out of bulk Li metal. Thus, a stable Li electrodeposition is realized with dendrite formations effectively suppressed. Various phenomena that enable the electrochemical stability of the anode, such as atomically layered structure and phase-transformation behaviour of the MoS2 layer, enhance the Li+ transport and conductivity between the electrolyte and Li metal. The full-cell assembly of Li–S batteries with a Li–MoS2 anode and a CNT–S cathode demonstrates high specific energy and power densities of 589 Wh kg−1 and 295 W kg−1, respectively; it also exhibits a high capacity retention of 84% for up to 1,200 cycles. These results indicate that the major challenge encountered in the development of Li–S batteries can be effectively resolved. We believe that this strategy can be applied with other 2D materials to provide a route for the development of high-performance Li-metal based rechargeable batteries.

Methods

Methods and any associated references are available in the online version of the paper.

Anode synthesis

A Li-metal ribbon (120 µm thick, Goodfellow) was stored and prepared for sputtering deposition in an Ar-filled glove box (MBraun) with the atmospheric condition of <0.5 ppm oxygen and humidity (H2O). The prepared Li metal was directly transferred over to the ultrahigh-vacuum chamber of a radiofrequency magnetron sputtering system. The sputtering depositions were carried out with a MoS2 target (two-inch diameter) from Plasmaterials (>99% purity). The base pressure in the sputtering chamber was maintained below 10−6 Torr; subsequently, the deposition was carried out at 10 mTorr with Ar gas (99.99%) plasma (running at 60 W). The MoS2 was sputtered onto Li-metal surface with various deposition times at room temperature. To determine the optimal thickness of the MoS2 layer, galvanostatic electroplating was carried out at a constant current of 1 mA cm−2 for each deposition time with a MACCOR 4000 battery tester. The thickness of the deposited MoS2 was determined by atomic force microscopy measurements on a blank SiO2 wafer retrieved from the same sputtering batch. The as-deposited MoS2-coated Li-metal samples were transferred back to the glove box and stamped into circular disks for further processing. For the lithiation process, the as-deposited MoS2-coated Li-metal disks were assembled into symmetric cells and cycled at a current density of 1 mA cm−2 for 15 cycles (30 min deposition/dissolution per cycle). For the full-cell test, the assembled cells were rested for at least 48 h to lithiate before starting the charge/discharge test.

Cathode synthesis

Cathodes were fabricated with sulfur powder (Sigma-Aldrich) and free-standing 3D CNTs. The 3D CNTs were grown via a chemical vapour deposition system as outlined previously12: 3D CNTs were grown on the catalyst (titanium/nickel)-coated copper mesh by introducing precursor gases (argon, hydrogen and ethylene) at an elevated temperature. Once the CNTs were grown, the copper mesh was etched with FeCl3 solution and rinsed with deionized water. After drying, sulfur was hot-pressed into the CNTs at 155 °C. Minimal load was applied (<5 kN) and the 3D CNT–S samples were under pressure until the desired loading amount of sulfur was acquired. No binder, conducting additive or metal current collector were used when synthesizing the cathodes.

Electrochemical characterization

CR2032 coin cells were used for all symmetric and half-cell tests. For the sake of consistency, 100 µl of electrolyte was used in each coin cell. The symmetric cells were composed of the electrodes (either MoS2-coated or bare Li metal), a separator (Celgard 2400) and an electrolyte (1 M lithium bis(trifluoromethanesulfonyl)imide (LiTFSI) in 1:1 DOL/DME solvent with no additives). The assembled symmetric cells underwent charge/discharge cycling tests through a Gamry Instrument (Reference 3000) to evaluate the cycling stability and cycle life of the anodes. Preceding the cycling test, all symmetric cells were pre-tested at a current density of 1 mA cm−2 for 15 cycles. The pre-cycling of the cell to activate the MoS2 layer offers a controllable, yet facile, process of lithiating a MoS2 layer to precisely optimize the uniform diffusion of Li42, 43. The symmetric cells were cycled at a current density of 10 mA cm−2 with 30 min dissolution/deposition time (1 h per cycle). The EIS measurements were carried out before and after cycling tests. For the half-cell tests, 25-µm-thick plain Cu foil and MoS2-coated Cu were used as the working electrodes. Li-metal foil was used as counter/reference electrode. Using the Gamry Instrument, the cells were pre-cycled at a rate of 0.1 mA cm−2 for up to 1 mAh cm−2 to stabilize the SEI. Subsequently, the current density was increased to 1 mA cm−2 with Li deposition/dissolution of 1 mAh cm−2 for up to 2 V.

For full-cell tests, 3D CNT–S was employed as cathode material with either MoS2-coated or bare Li metal as the anode. Cyclic voltammetry and EIS were carried out using a Gamry potentiostat. The EchemAnlayst software (Gamry Instrument) was utilized to fit the Nyquist plot corresponding to the equivalent circuit model. The electrochemical performance of Li–MoS2/CNT–S and Li/CNT–S full cells were evaluated by a multi-channel battery testing unit (MACCOR-series 4000). The coin cells (CR 2032, Welcos) were fabricated inside an Ar-filled glove box (MBraun) maintaining the humidity (H2O) and oxygen (O2) concentration below 0.5 ppm. A standard Li–S cell electrolyte was prepared by using LiTFSI salt (99% Sigma Aldrich, 1 M) and lithium nitrate (LiNO3, 99.99%, Sigma-Aldrich, 0.25 M) as electrolyte additive in the organic solvent of 1,2-dimethoxyethane (DME, 99.5%, Sigma-Aldrich) and 1,3-dioxolane (DOL, 99%, Sigma-Aldrich) with 1:1 volumetric ratio. Commercially available polypropylene (2400, Welcose) was used as a separator. The electrolyte amount added to the full cells was optimized to 60 µl. GCD tests were carried out at room temperature within a voltage range of 1.5–3.0 V. The areal density of 3D CNTs was approximately ~7 mg cm−2 and the loading amount of sulfur was 3.44 mg cm−2. The cathode (3D CNT–S) contained 33 wt% of sulfur in the whole cathode electrode. The C rate was calculated based on the theoretical specific capacity of sulfur ((Qs = 2 × 9.65 × 104 / (3.6 × 32.065)) ≈ 1,672 mAh g−1). The specific energy and power of the Li–MoS2/CNT–S cell was calculated using the following equations with the mass of the entire cathode (sulfur and CNTs) taken into account (see Supplementary Note 4 for detailed calculations along with the overall weight of the cell considered):

Structural and surface characterizations

The morphologies of MoS2-coated and bare Li metal were analysed with SEM (FEI, Verios) and TEM (FEI, Tecnai) at an accelerating voltage of 5 and 120 kV, respectively. Before the SEM analysis, the tested coin cells were dissembled in the glove box to retrieve the anodes and rinsed with DME solvent and dried to eliminate residual electrolytes. The samples were then placed onto a sealable SEM holder (Supplementary Fig. 18a) and vacuum packaged to minimize atmospheric contamination during transfer. For the EDS measurements, a cross-section of MoS2-coated Li metal was prepared by vertically cutting the samples with a razor-sharp blade. Almega XR spectrometer with a green laser of 532 nm was used to collect Raman spectra. To minimize atmospheric contamination, a tiny drop of poly(methyl methacrylate) was applied to the surface of the samples prepared in the glove box (Supplementary Fig. 18b). XPS was carried out with PHI 5000 Versaprobe-II using a monochromatic Al Kα with 25.2 W at 100 µ resolution. The MoS2-coated and bare Li samples were vacuum packaged in the glove box and directly transferred to the vacuum chamber of the XPS system. To prepare the samples for TEM analysis, the MoS2-coated Li metal was submerged in hexane and sealed against air in Ar-filled glove box; subsequently, the sealed vessel was taken out and sonicated for 30 min before loading it back into the glove box. Two to three drops of the sonicated solution were applied to the TEM grid using a micro-pipet. After drying, the prepared samples were vacuum packaged for the transfer.

Simulations

All DFT44 calculations were performed using projector-augmented wave pseudopotentials45 implemented in the Vienna ab initio simulation package (VASP)46, 47. Local density approximation for exchange-correlation functional was known to give a better description for a binding energy and an interlayer spacing of the layered structure than PBE potential48. Therefore, local density approximation was employed to handle bulk and monolayer MoS2 in a consistent way without using an empirical van der Waals energy correction for layered systems. The energy cut-off for the plane-wave basis point was set to 700 eV for structural optimizations of a hexagonal unit cell. The solid-state nudged elastic band methods49 were employed to calculate the kinetic energy barrier along the Li migration pathways, where the energy cut-off for the plane-wave basis point was set to 400 eV. All internal coordinates were relaxed until the force on each atom was less than 0.02 eV Å−1. For nudged elastic band calculations, a 4 × 4 supercell was employed with a uniform k-point grid of 2 × 2 × 2 for bulk and 2 × 2 × 1 for monolayer, respectively.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Change history

04 April 2018

In the version of this Article originally published, a technical error in typesetting led to the traces in Fig. 3a being trimmed and made to overlap. The figure has now been corrected with the traces as supplied by the authors; the original and corrected Fig. 3a are shown below. Also, in the last paragraph of the section “Mechanistic study on Li diffusion in MoS2” the authors incorrectly included the term ‘high-concentration’ in the text “the Li diffusion will be dominated by high-concentration Li migration on the surface of T-MoS2 with a much smaller energy barrier (0.155 eV) to overcome”. This term has now been removed from all versions of the Article. Finally, the authors have added an extra figure in the Supplementary Information (Supplementary Fig. 19) to show galvanostatic tests at 1 and 3 mA cm–2 for the MoS2-coated Li symmetric cells. The caption to Fig. 3 of the Article has been amended to reflect this, with the added wording “Galvanostatic tests at 1 and 3 mA cm–2 can be found in Supplementary Fig. 19.”

References

Grande, L. et al. The lithium/air battery: still an emerging system or a practical reality? Adv. Mater. 27, 784–800 (2015).

Lu, Y. et al. Stable cycling of lithium metal batteries using high transference number electrolytes. Adv. Energy Mater. 5, 1402073 (2015).

Xu, W. et al. Lithium metal anodes for rechargeable batteries. Energy Environ. Sci. 7, 513–537 (2014).

Manthiram, A., Fu, Y., Chung, S. H., Zu, C. & Su, Y. S. Rechargeable lithium–sulfur batteries. Chem. Rev. 114, 11751–11787 (2014).

Yamin, H., Gorenshtein, A., Penciner, J., Sternberg, Y. & Peled, E. Lithium sulfur battery. Oxidation/reduction mechanisms of polysulfides in THF solutions. J. Electrochem. Soc. 135, 1045–1048 (1988).

Peled, E. The electrochemical behavior of alkali and alkaline earth metals in nonaqueous battery systems—the solid electrolyte interphase model. J. Electrochem. Soc. 126, 2047–2051 (1979).

Li, G. et al. Three-dimensional porous carbon composites containing high sulfur nanoparticle content for high-performance lithium–sulfur batteries. Nat. Commun. 7, 10601 (2016).

Ma, L. et al. Enhanced Li–S batteries using amine-functionalized carbon nanotubes in the cathode. ACS Nano 10, 1050–1059 (2016).

Xiao, Z. et al Lightweight TiO2/graphene interlayer, applied as a highly effective polysulfide absorbent for fast, long-life lithium–sulfur batteries. Adv. Mater. 27, 2891–2898 (2015).

Jin, S. et al. Covalently connected carbon nanostructure for current collectors in both the cathode and anode of Li–S batteries. Adv. Mater. 28, 9094–9102 (2016).

Patel, M. D., Cha, E., Kang, C., Gwalani, B. & Choi, W. High performance rechargeable Li–S batteries using binder-free large sulfur loaded three-dimensional carbon nanotubes. Carbon 118, 120–126 (2017).

Qian, J. et al. High rate and stable cycling of lithium metal anode. Nat. Commun. 6, 6362 (2015).

Ding, F. et al. Dendrite-free lithium deposition via self-healing electrostatic shield mechanism. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 4450–4456 (2013).

Zhang, J. et al. Superior conductive solid-like electrolytes: nano confining liquids within the hollow structures. Nano Lett. 15, 3398–3402 (2015).

Dudney, N. J. Addition of a thin-film inorganic solid electrolyte (lipon) as a protective film in lithium batteries with a liquid electrolyte. J. Power Sources 89, 176–179 (2000).

Zheng, G. Y. et al. Interconnected hollow carbon nanospheres for stable lithium metal anodes. Nat. Nanotech. 9, 618–623 (2014).

Lee, H., Lee, D. J., Kim, Y.-J., Park, J.-K. & Kim, H.-T. A simple composite protective layer coating that enhances the cycling stability of lithium metal batteries. J. Power Sources 284, 103–108 (2015).

Kozen, A. C. et al. Next-generation lithium metal anode engineering via atomic layer deposition. ACS Nano 9, 5884–5892 (2015).

Yan, K. et al. Ultrathin two-dimensional atomic crystals as stable interfacial layer for improvement of lithium metal anode. Nano Lett. 14, 6016–6022 (2014).

Zhang, R. et al. Conductive nanostructured scaffolds render low local current density to inhibit lithium dendrite growth. Adv. Mater. 28, 2155–2162 (2016).

Aurbach, D., Zinigrad, E., Cohen, Y. & Teller, H. A short review of failure mechanisms of lithium metal and lithiated graphite anodes in liquid electrolyte solutions. Solid State Ion. 148, 405–416 (2002).

Lu, Y., Tu, Z. & Archer, L. A. Stable lithium electrodeposition in liquid and nanoporous solid electrolytes. Nat. Mater. 13, 961–969 (2014).

Wang, D. et al. Towards high-safe lithium metal anodes: suppressing lithium dendrites via tuning surface energy. Adv. Sci. 4, 1600168 (2017).

Wang, Q. H., Kalantar-Zadeh, K., Kis, A., Coleman, J. N. & Strano, M. S. Electronics and optoelectronics of two-dimensional transition metal dichalcogenides. Nat. Nanotech. 7, 699–712 (2012).

Chhowalla, M. et al. The chemistry of two-dimensional layered transition metal dichalcogenide nanosheets. Nat. Chem. 5, 263–275 (2013).

Dickinson, R. G. & Pauling, L. The crystal structure of molybdenite. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 45, 1466–1471 (1923).

Bieker, G., Winter, M. & Bieker, P. Electrochemical in situ investigations of SEI and dendrite formation on the lithium metal anode. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 17, 8670–8679 (2015).

Nayak, A. P. et al. Pressure-dependent optical and vibrational properties of monolayer molybdenum disulfide. Nano Lett. 15, 346–353 (2014).

Py, M. & Haering, R. Structural destabilization induced by lithium intercalation in MoS2 and related compounds. Can. J. Phys. 61, 76–84 (1983).

Santa Ana, M., Mirabal, N., Benayenta, E., Gomez-Romero, P. & Gonzalez, G. Electrochemical behavior of lithium intercalated in a molybdenum disulfide-crown ether nanocomposite. Electrochim. Acta 53, 1432–1438 (2007).

Teng, Y. et al. MoS2 nanosheets vertically grown on graphene sheets for lithium-ion battery anodes. ACS Nano 10, 8526–8535 (2016).

Nayak, A. P. et al. Pressure-induced semiconducting to metallic transition in multilayered molybdenum disulphide. Nat. Commun. 5, 3731 (2014).

Yang, L. et al. Lattice strain effects on the optical properties of MoS2 nanosheets. Sci. Rep. 4, 5649 (2014).

Kappera, R. et al. Phase-engineered low-resistance contacts for ultrathin MoS2 transistors. Nat. Mater. 13, 1128–1134 (2014).

Fang, R. et al. 3D interconnected electrode materials with ultrahigh areal sulfur loading for Li–S batteries. Adv. Mater. 28, 3374–3382 (2016).

Zhang, S. S. New insight into liquid electrolyte of rechargeable lithium/sulfur battery. Electrochim. Acta 97, 226–230 (2013).

Kim, H., Lee, J., Ahn, H., Kim, O. & Park, M. J. Synthesis of three-dimensionally interconnected sulfur-rich polymers for cathode materials of high-rate lithium–sulfur batteries. Nat. Commun. 6, 7278 (2015).

Zhao, M.-Q. et al. Hierarchical vine-tree-like carbon nanotube architectures: in-situ CVD self-assembly and their use as robust scaffolds for lithium-sulfur batteries. Adv. Mater. 26, 7051–7058 (2014).

Song, M.-K., Zhang, Y. & Cairns, E. J. A long-life, high-rate lithium/sulfur cell: a multifaceted approach to enhancing cell performance. Nano Lett. 13, 5891–5899 (2013).

Zhao, M.-Q. et al. Unstacked double layer templated graphene for high-rate lithium–sulphur batteries. Nat. Commun. 5, 3410 (2014).

Zhou, Y. et al. Enabling prominent high-rate and cycle performances in one lithium–sulfur battery: designing perm-selective gateways for Li+ transportation in holey-CNT/S cathodes. Adv. Mater. 27, 3774–3781 (2015).

Liu, Q.-C. et al. Artificial protection film on lithium metal anode toward long-cycle-life lithium–oxygen batteries. Adv. Mater. 27, 5241–5247 (2015).

Cheng, X.-B. et al. Implantable solid electrolyte interphase in lithium-metal batteries. Chem 2, 258–270 (2017).

Hohenberg, P. & Kohn, W. Inhomogeneous electron gas. Phys. Rev. 136, B864–B871 (1964).

Kresse, G. & Joubert, D. From ultra-soft pseudopotentials to the projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 59, 1758–1775 (1999).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B 54, 11169–11186 (1996).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficiency of ab-initio total energy calculations for metals and semiconductors using a plane-wave basis set. Comput. Mater. Sci. 6, 15–50 (1996).

Petrova, N. V., Yakovkin, I. N. & Zeze, D. A. Metallization and stiffness of the Li-intercalated MoS2 bilayer. Appl. Surf. Sci. 353, 333–337 (2015).

Sheppard, D., Xiao, P., Chemelewski, W., Johnson, D. D. & Henkelman, G. A generalized solid-state nudged elastic band method. J. Chem. Phys. 136, 074103 (2012).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank J. Tour for discussions. We also thank KIST Jeonbuk (Korea Institute of Science and Technology at Jeonbuk) for providing the facility to carry out HRTEM and B. Gwalani for helping out with additional EDX analysis. W.C. acknowledges partial financial support from SEED fund at University of North Texas. K.C. acknowledges a part of financial support by the International Energy Joint R & D Program (No. 20168510011350) of the Korea Institute of Energy Technology Evaluation and Planning (KETEP), the Ministry of Knowledge Economy and the National Research Foundation of Creative Materials Discovery Program (2015M3D1A1068062).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

W.C. conceived the idea and designed the experiments. E.C. performed the cell fabrication, battery testing, SEM and TEM characterizations. W.C. and E.C. wrote the manuscript. M.D.P. performed the EIS measurements and cathode characterization. J.P. performed nano coating and analysed the Raman and XPS data. J.H. and K.C. performed the numerical simulation and provided data analysis. V.P. analysed the materials characterization data and edited the manuscript. All authors have discussed the results, read the manuscript and agreed with its content.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Notes 1–4 and Supplementary Figures 1–19, Supplementary Tables 1–2.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Cha, E., Patel, M.D., Park, J. et al. 2D MoS2 as an efficient protective layer for lithium metal anodes in high-performance Li–S batteries. Nature Nanotech 13, 337–344 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41565-018-0061-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41565-018-0061-y

This article is cited by

-

Composite protective coating on lithium metal anodes for polysulfide shielding in lithium-sulfur batteries

Science China Materials (2025)

-

Reducing the shuttle effect in Li-S batteries with oxygenated penta-SiC₂ monolayer

Ionics (2025)

-

Nacre-inspired hybrid interface enabling controlled lithium deposition via ion modulation for lithium–sulfur batteries

Advanced Composites and Hybrid Materials (2025)

-

Review: Metal-based quantum dots as functional interlayers in lithium–sulfur batteries: interfacial catalysis and stability regulation

Journal of Materials Science (2025)

-

Tailoring Artificial Solid Electrolyte Interphase via MoS2 Sacrificial Thin Film for Li-Free All-Solid-State Batteries

Nano-Micro Letters (2025)