Abstract

Solution-processed light-emitting diodes (LEDs) based on copper–iodide clusters are promising candidates for solid state lightings due to their abundance, environmental friendliness and high luminescent efficiency. However, the development of this class of LEDs is hampered by the instability of the clusters, poor solution compatibility and low film quality, resulting in poor device performances. Here we report a new type of copper–iodide cluster hybrids with functional groups that facilitate both solubility and stability of the clusters. The hybrid clusters exhibit high structural stability in solvents, enabling smooth solution-processed thin films with low surface roughness of 0.22 nm and high photoluminescence quantum yields of over 70%. We employ the high-quality thin film as an emissive layer in warm-white LEDs, showing a maximum external quantum efficiency of 19.1%, maximum high brightness of over 40,000 cd m−2 and a good operational lifetime of 232 h (T50 at an initial luminance of 100 cd m−2). We also demonstrate a large-area LED with brightnesses of up to ~60,000 cd m−2 through blade-coating and a series of colour-tunable LEDs based on ligand modifications. Our results suggest great potential of copper–iodide cluster-based LEDs for practical applications in panel display and solid-state lighting.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Solution-processed light-emitting diodes (LEDs) are regarded as a promising foundation for the next-generation large-area solid state lighting technology due to their simple manufacturing process1,2,3. Currently, LEDs based on lead-halide perovskites4, organic semiconductors5 and colloidal core–shell quantum dots (QDs)6 as emitting layers via solution-processed methods have been demonstrated with high electroluminescent performances. However, solution-processed LEDs based on heavy metals such as lead-halide perovskites7 and CdSe QDs8 are subjected to grave challenges of environmental issues, whereas those based on organic luminescent molecules9,10, InP QDs11 and ZnSe QDs12 with toxic-metal-free features suffer from the high cost attributed to the complicated design and synthetic process. The above-mentioned problems will hinder their practical applications and lead to some difficulties in large-scale fabrication. Developing cost effective, eco-friendly, easily scalable emitters for solution-processed LEDs is therefore of vital importance on future low-cost and efficient solid-state lightings.

Copper–iodide cluster-based hybrids have recently come into view due to their earth abundance, low toxicity, optical tunability and high luminescent efficiency13,14,15. With efforts on functionalizing the organic components and optimizing the host–dopant structures, the implementation of these copper–iodide cluster-based emitters for noble/toxic metal-free LEDs is gradually demonstrated with satisfactory efficiency16,17,18,19. Nevertheless, the fabrication of solution-processed LEDs based on copper–iodide cluster-based emitters so far has to face the challenges of poor solution processability and compatibility in solvents of presently reported copper–iodide hybrid clusters16,17,20,21, together with the complicated host–dopant or antisolvent treatment for the thin films as emissive layers in LEDs16,18,19. To address these issues, the judicious design of highly luminescent copper–iodide cluster-based emitters to enable solution-processing high quality thin films for LEDs is in high demand.

Herein we report the fabrication of efficient and bright LEDs based on solution-processed copper–iodide (Cu2I2) cluster-based hybrids, using diphenyl-2-pyridylphosphine (abbreviated as Pyrphos) as bridging ligands and tris(3-methylphenyl)phosphine (abbreviated as P-(m-Tol)3) as solubility-enhancing groups. The as-designed Cu2I2[P-m-(Tol)3]2Pyrphos (abbreviated as CuI-Pyrphos) exhibits ultra-high solubility and stability in dimethylformamide (DMF) to enable solution-processed thin films. The thin film obtained as the emissive layer is well incorporated into the solution-processed LED, with a maximum external quantum efficiency (EQE) of 19.1% and high brightnesses of over 40,000 cd m−2. The solution-processing CuI-Pyrphos also enables a large-area, bright, warm-white LED of 36 cm2 via blade-coating. Moreover, the electroluminescence spectra of these solution-processing copper–iodide hybrid LEDs can be feasibly tuned by modifying the electronic characteristics of the Pyrphos heterocycle ligands.

The emissive layers in our CuI-Pyrphos LEDs are processed from the DMF solution (Fig. 1a). Dimethylformamide is an orthogonal solvent22 with the chlorobenzene for the hole transport layer of poly(9-vinylcarbazole (PVK), which could prevent the dissolving and blending of functional layers and stabilize them against slow diffusion during the device fabrication20,23,24. Based on the energy level of the CuI-Pyrphos thin film (Supplementary Fig. 1), our LED devices were fabricated by the deposition of sequential layers onto the indium tin oxide (ITO)-coated glass substrates by the order of poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene)-poly(styrenesulfonate) (PEDOT:PSS), poly(N,N′-bis(4-butylphenyl)-N,N′-bis(phenyl)-benzidine) (poly TPD), PVK, CuI-Pyrphos, 1,3,5-tris(3-pyridyl-3-phenyl)benzene (TmPyPB), LiF and aluminium (Fig. 1b). The performance characteristics of the fabricated CuI-Pyrphos LEDs are shown in Fig. 1c–g. The electroluminescence spectrum performs a broad peak centred at ~560 nm with a wide full-width at half-maximum of 120 nm (Fig. 1c), indicating the warm-white light emission of the device. The different shapes of photoluminescence and electroluminescence spectra can be attributed to the influence of electric field on the CuI-Pyrphos cluster (Supplementary Fig. 2). A photograph of the fabricated LED (inset in Fig. 1c) shows the bright warm-white light emission under an applied voltage of 6 V. Figure 1d shows the current density–voltage (J–V) characteristics and the luminance–voltage (L–V) curves of the fabricated CuI-Pyrphos LED. The luminance rises rapidly after a voltage of ~4 V and shows a maximum brightness of 42,873 cd m-2 at ~15 V. The peak EQE reaches up to 19.1% at a luminance of 269 cd m−2 (Fig. 1e), which is close to the theoretical maximum EQE (22.2%) based on the device structure analysis (Supplementary Figs. 3 and 4). The device performance is superior to that of the reported CsPbI3-based white-light LED (Supplementary Table 1)25 and exceeds those of previously reported lead-free metal halide LEDs (Supplementary Table 2)18,19,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36. We measured a total of twenty devices and the histogram of peak EQEs shows a high average value of ~18.2% (inset in Fig. 1e), indicating the good reproducibility of our developed solution-processed CuI-Pyrphos LEDs.

a, Schematic fabrication procedure of highly luminescent CuI-Pyrphos thin film by spin coating CuI-Pyrphos in DMF on a PVK layer with subsequent thermal annealing treatment. b, The configuration and corresponding energy-level diagram of different functional layers of the CuI-Pyrphos LED. c, Electroluminescence spectrum at an operation voltage of 6 V for CuI-Pyrphos LED. The inset is a photograph of the fabricated device with an applied voltage of 6 V. Scale bar, 1 cm. d, Current density and luminance versus driving voltage curves for a CuI-Pyrphos LED. e, The EQE versus different luminance curve of the CuI-Pyrphos LED. The inset is a histogram of the maximum EQEs of CuI-Pyrphos LEDs. f, Operation lifetime testing curves at different initial luminances (L0) for CuI-Pyrphos LEDs. The horizontal dashed line is marked to indicate the T50 lifetime (where the electroluminescence intensity decreased to the half of the maximum value). g, The T50 lifetimes as a function of L0; the solid line is the fitting of T50 data to equation R0n × T50 = constant, where n is the acceleration factor.

Moreover, the performance and stability of our CuI-Pyrphos LEDs prepared without any host materials are notably better than those dopant structures with a bis-4-(N-carbazolyl)phenyl)phenylphosphine oxide host matrix in the emissive layers (Supplementary Figs. 5 and 6), further demonstrating the benefits of our solution-processed thin films for the host-free LEDs. We also tested the operational stability of our CuI-Pyrphos LED as shown in Fig. 1f. The stability of the LEDs was analysed by applying a constant current and monitoring the luminance in a N2-filled glovebox. The operational lifetime of LEDs was measured at various initial luminances from 1,426 cd m−2 to 25,073 cd m−2. By using the empirical scaling law of accelerated lifetime equation (R0n × T50 = constant, where n is an acceleration factor) with n = 1.2, we estimated the T50 of the device at 100 cd m−2 to be approximately 232 h (Fig. 1g)37,38,39. To the best of our knowledge, this represents a record operational stability of solution-processed lead-free metal halide LEDs (Supplementary Table 2).

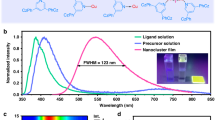

To understand the origins of the high performances of CuI-Pyrphos LEDs, we investigated the properties of the CuI-Pyrphos and its existing status during solution processing. We highlight that the high solubility and processability—as well as the robust structure and excellent optical stabilities of CuI-Pyrphos in DMF—are of vital importance. The CuI-Pyrphos contains two P-(m-Tol)3 ligands as solubility-enhancing groups, together with a Pyrphos heterocycle as a bridging ligand, which can be synthesized in one-pot reaction by mixing CuI and corresponding organic ligands (Methods). The obtained CuI-Pyrphos powders show bright yellow light emission (Fig. 2a) with a high photoluminescence quantum yield (PLQY) of 82.8% (λex = 365 nm) and a relatively broad photoluminescence spectrum (Supplementary Fig. 2), which mainly results from the multiple charge transfer excited states including not only a metal-to-ligand charge transfer state, but also an iodine-to-ligand charge transfer state. By multistep cooling the thermally saturated CuI-Pyrphos/acetonitrile solution, we obtained single crystals of CuI-Pyrphos (Methods). Based on single-crystal X-ray diffraction analysis (Supplementary Table 3), the obtained CuI-Pyrphos cluster is determined to behave as a zero-dimensional structure, in which a Cu2I2 unit is chelated by a Pyrphos-ligand and two additional monodentate P-(m-Tol)3 ligands, as shown in Fig. 2b. The introduction of a nitrogen-containing Pyrphos ligand ensures the luminescence tunability of the cluster and effectively bridges two copper atoms to form a strong single-sided chelate structure, further guaranteeing good structure stability of CuI-Pyrphos cluster (Supplementary Fig. 7). It is striking that the solubility of CuI-Pyrphos in various organic solvents is largely improved (Supplementary Table 4) compared with previously reported copper–iodide cluster-based hybrids13,14,40. We attribute this behaviour to the high asymmetry of the meta-tolyl substituents in the P-m-(Tol)3 ligands41, and the electrostatic interactions between CuI-Pyrphos and DMF for solvation (Supplementary Fig. 8).

a, Photographs of the as-synthesized CuI-Pyrphos powder under ambient light (left) and the irradiation of ultraviolet light (365 nm) (right). b. The fine-structure model of the CuI-Pyrphos cluster. All hydrogen atoms are omitted for clarity. c, 31P NMR spectra of a P-m-(Tol)3 ligand, Pyrphos ligand and CuI-Pyrphos dissolved in DMF-d7. d, XANES spectra at Cu K-edge (E0 = 8,979 eV) versus photon energy of the standard copper foil, the standard CuO, the powder sample of CuI-Pyrphos and the solution sample of CuI-Pyrphos dissolved in DMF. e, The amplified near-edge region of the copper K-edge XANES spectra. f, FT[k3χ(k)] EXAFS data of the powder sample of CuI-Pyrphos. R, the interatomic distance in radial distribution function, in which the absorbing atom is located at the origin; ΔR, the phase shift. g, FT[k3χ(k)] EXAFS data of the solution sample of CuI-Pyrphos dissolved in DMF. h, In situ UV–vis absorption spectra during the precipitation process of CuI-Pyrphos powder formation. i, In situ photoluminescence spectra (λex = 375 nm) during the precipitation process of CuI-Pyrphos powder formation. a.u., arbitrary units.

We further explored the cluster structural stability of CuI-Pyrphos in DMF by nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) and synchrotron-based X-ray absorption spectroscopy (XAS). The 31P NMR spectra peaks of CuI-Pyrphos show a slight chemical shift compared with that of individual ligands, which is indicative of the presence of coordination interactions among phosphorus donors and Cu2I2 inorganic units, even under a solution environment (Fig. 2c). X-ray absorption spectra were collected at the CuK edge to probe the local coordination geometry of the CuI centres in the CuI-Pyrphos hybrids. The oxidation state of the copper centre can be estimated from the X-ray absorption near-edge structure (XANES) spectra as shown in Fig. 2d,e. The energy positions of absorption edges of the powder sample and the solution sample are almost overlapping, which are also well separated from the absorption edges of the reference standard samples of CuO and copper foil. It can thus be concluded that the oxidation state of the copper centre in both powder and solution sample is basically between 0 and +2. The extended X-ray absorption fine structure (EXAFS) region was further analysed to give insights on the coordination numbers and bond lengths of nearest-neighbour atoms around copper centres (Fig. 2f,g). The fine fitting results of both powder and solution samples of CuI-Pyrphos are shown in Supplementary Table 5, providing information on coordination numbers and nearest-neighbour interatomic distances of Cu–Cu, Cu–I, Cu–N and Cu–P. There are no considerable differences between the EXAFS data of both powder and solution samples, suggesting that coordination geometry around the copper centres, as well as the number and type of the nearest-neighbour atoms, is similar for both powder and solution samples. Based on the accumulated evidences, we can safely conclude that the cluster structure of CuI-Pyrphos is well maintained in DMF solution. We also collected the in situ ultraviolet–visible (UV–vis) and photoluminescence spectra in the solution state and during the precipitation process of powder formation. As shown in Fig. 2h,i, the UV–vis absorption spectra of the sample barely changed while the solvent gently evaporated out from the CuI-Pyrphos/DMF solution, whereas the photoluminescence intensity evidently increased and the bright yellow emissive CuI-Pyrphos powder precipitated out again, further indicating the structural maintenance and the optical reversibility of CuI-Pyrphos in DMF solution.

The robustness of CuI-Pyrphos in DMF facilitates the solution processing of emissive layers for LEDs. As shown in Fig. 3a, the amorphous CuI-Pyrphos thin film fabricated by spin-coating exhibits the emission of a bright yellow light under ultraviolet light irradiation. The high-resolution transmission electron microscopy image (Fig. 3b) and selected area electron diffraction pattern (inset in Fig. 3b) further revealed the amorphous state of the fabricated thin film, which is conducive to avoid the carrier quenching caused by morphological defects such as crystalline grains in LEDs20,42. The atomic force microscopy (AFM) image (Fig. 3c) further confirms the smooth and uniform surface of the spin-coated CuI-Pyrphos thin film with a surface roughness value of 0.216 nm. We then investigated the electrical transport property of the CuI-Pyrphos thin film with a device structure of ITO/CuI-Pyrphos (40 nm)/Al(160 nm) (Supplementary Fig. 9). By fitting the I–V curve, the conductivity of CuI-Pyrphos thin film is determined to be 1.7 × 10−6 Ω−1 cm−1, which is comparable with that of the reported all-in-one typed copper–iodide cluster based compound18. Furthermore, the estimated hole and electron mobility values from space-charge-limited current tests are 1.37 × 10−5 cm2 V−1 S−1 and 1.12 × 10−6 cm2 V−1 S−1, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 10), further suggesting a satisfactory charge-transport property for the host-free LEDs based on CuI-Pyrphos films.

a, Powder X-ray diffraction pattern of the spin-coated CuI-Pyrphos thin film. The inset is a photograph of the spin-coated CuI-Pyrphos thin film under the irradiation of ultraviolet light (365 nm). Scale bar, 0.5 cm. b, Transmission electron microscopy image of the CuI-Pyrphos thin film. The inset shows the corresponding selected area electron diffraction pattern of the film. Scale bar, 5 nm−1. c, Atomic force microscopy image of the spin-coated CuI-Pyrphos thin film. Ra, arithmetic mean roughness. d,e, Photoluminescence spectra (d) and photoluminescence decay (e) curves of CuI-Pyrphos films at various temperatures (λex = 320 nm). The photoluminescence decay curves are well fit with the double exponential function to determine the photoluminescence lifetime. f, Photographs of the blade-coated CuI-Pyrphos thin film under ambient light (left) and ultraviolet light (365 nm) irradiation (right). g, Atomic force microscopy image of the blade-coated CuI-Pyrphos thin film. h, The device structure of the fabricated large-area LED. i, A photograph of the fabricated large-area CuI-Pyrphos LED with a device area of 6 × 6 cm2.

We examined PLQY values, photoluminescence spectra and photoluminescent decay lifetimes of the CuI-Pyrphos thin film at 77–298 K to clarify its photoluminescence mechanism and corresponding emission states (Fig. 3d,e). The radiative rate (kr = ΦPLτ−1) of 6.1 × 103 s−1 at 77 K implies an efficient spin–orbit coupling effect (T1–S0 transition) in the cluster. The change in the radiative rate to 1.4 × 104 s−1 when temperature increases to 298 K is related to the growing photoluminescent involvement of the upper-lying first excited singlet state S1 with a higher radiative rate. The results suggest that the photoluminescent emissions of the CuI-Pyrphos film originate from two thermally equilibrated excited S1 and T1 states. The investigation of the temperature dependence of the photoluminescence decay lifetime is an effective approach to determine specific emission factors. Assuming a fast thermal equilibrium between the involved S1 and T1 states, and considering the degenerate substrates of the T1 state, the obtained data (overall decay lifetime τ) can be fitted by a modified Boltzmann relation according to the following equation43,44:

where kB and T represent the Boltzmann constant and the absolute temperature, respectively. By fitting the above equation to the experimental data of overall decay lifetimes at various temperatures (Supplementary Fig. 11a), we obtain the values of individual decay lifetimes of S1 (τ(S1) = 260 ns), T1 (τ(T1) = 10.9 μs), and the energy gap between the S1 and T1 states (ΔEST = 0.052 eV), respectively. Based on the efficient spin–orbit coupling and the calculated small activation energy ΔEST, the photoluminescence of CuI-Pyrphos film stems from two radiative recombination paths: thermally activated delayed fluorescence (TADF) and phosphorescence. Sequentially, we estimated the relative contributions of TADF and phosphorescence in the overall temperature-dependent emission (Supplementary Fig. 11b)44. At very low temperatures, the population is predominantly frozen in the T1 state, and thus the CuI-Pyrphos film mainly emits phosphorescence. Upon increasing the temperature, the thermal population of the higher-lying S1 state increases and the intensity contribution of phosphorescence decreases. At room temperature (298 K), TADF and phosphorescence account for 65% and 35% of the overall emission, respectively.

The high quality of the CuI-Pyrphos thin film with bright light emission, amorphous state, smooth surface and short photoluminescence lifetime at room temperature contributes to good performances of the fabricated LEDs. We prepared a thin film with an area of 6 × 6 cm2 (36 cm2) via a blade-coating method to manifest the scalability of solution-processing CuI-Pyrphos. The CuI-Pyrphos/DMF solution could spread over the entire substrate and the obtained transparent thin film exhibited bright yellow light emission under ultraviolet light irradiation (Fig. 3f). The blade-coated thin film is notably extremely uniform over the whole substrate with a surface roughness of only 0.220 nm (Fig. 3g), which is comparable with that of spin-coated thin films. We then fabricated a large-area LED employing the blade-coated CuI-Pyrphos thin film as the emissive layer with the device structure of ITO, PEDOT:PSS, poly-TPD, PVK, CuI-Pyrphos, TPBi, LiF and aluminium (Fig. 3h). The as-fabricated LED with an active area of 36 cm2 displayed highly bright and uniform warm-white light emission with brightnesses of up to ~60,000 cd m−2 (Fig. 3i and Supplementary Fig. 12), indicating a potential of mass fabrication of CuI-Pyrphos LEDs for flat-panel lighting.

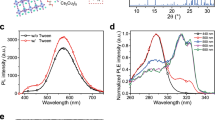

To expand the colour of our solution-processed LEDs, we employed the ligand-modification strategy to tuning the light emission of the synthesized Cu2I2 cluster-based hybrids. As their optical properties are dependent on the nature of the N-heterocycle of bridging ligands (Supplementary Fig. 13)21,40, we synthesized different bridging ligands with desired electronic properties without changing the P-m-(Tol)3 ancillary ligands. All of the synthetic organic ligands with electron-donating groups were confirmed by 1H NMR analysis (Supplementary Figs. 14–16). A series of highly luminescent Cu2I2 hybrids of CuI-Mepyrphos, CuI-Mepenpyrphos and CuI-Nme2pyrphos are obtained. The photoluminescence spectra and estimated band gap values are shown in Fig. 4a–c and Supplementary Figs. 17–19, showing that the modulated photoluminescence emission wavelengths span from yellow to green and a trend of band gaps follows the ascending order of electron-donating abilities of the corresponding ligands. Based on the accumulated results from XRD and thermogravimetric analysis (Supplementary Figs. 20 and 21), we deduced that all of the obtained Cu2I2 hybrids are structured on the basis of a Cu2I2 core, a bridging ligand and two P-m-(Tol)3 as ancillary ligands. All the extended samples held the PLQYs approaching to ~90% and can be well processed in DMF to be readily coated on the substrates to form emissive layers for LED devices (insets in Fig. 4a–c). Accordingly, efficient and bright blue–green and green–yellow LEDs with EQEs of 6.7–16.6% and brightness of 8,119–26,644 cd m−2 were obtained (Fig. 4d–f).

a–c, Photoluminescence spectra (λex = 365 nm) of CuI-Mepyrphos (a), CuI-Mepenpyrphos (b) and CuI-Nme2pyrphos (c) thin films. The insets are diagrams of energy level positions (left), structures of extended ligands (middle) and photographs of spin-coated thin films of corresponding CuI-ligand hybrids (right). Scale bars, 0.5 cm. d,e, Current density (d) and luminance (e) versus driving voltage curves for the LEDs based on extended CuI-ligand hybrids. f, The EQE versus luminance curves of the LEDs based on extended CuI-ligand hybrids. Insets are photographs of the corresponding fabricated devices based on CuI-Mepyrphos (left), CuI-Mepenpyrphos (middle) and CuI-Nme2pyrphos (right). Scale bars, 1 cm.

Conclusion

In summary, a series of solution-processed LEDs based on well-designed copper–iodide cluster based hybrids have been demonstrated with high EQEs of up to 19.1%. The reported copper–iodide cluster-based hybrids exhibit high solubility, great structural stability and processability in DMF to facilitate the low-cost solution-processed LEDs through an orthogonal solvent route. Furthermore, the large-area LED incorporating the high-quality, blade-coated CuI-Pyrphos thin film with a working area of 36 cm2 exhibits uniform and bright warm-white light emission, highlighting the advantages of this solution-processed copper–iodide cluster-based LED. The light-emitting colours of the LEDs can also be tuned by modifying electron-donating groups in organic bridging ligands. Our work presents a novel copper–iodide cluster hybrid design for the fabrication of low-cost solution-processed LEDs with promising prospects for solid state lightings.

Methods

General route for the synthesis of the Cu2I2-based hybrid powders

CuI (1 mmol, 2 equiv.), P-(m-Tol)3 (1 mmol, 2 equiv.) and heterocycle bridging ligands (0.50 mmol, 1 equiv.) were suspended in 20 ml of acetonitrile under a nitrogen atmosphere in the dark and stirred for 15 min in a reaction vial. The solution was filtered over a polyvinylidene fluoride filter (0.22 µm) when the mixture became clear, and the filtrate was concentrated by vacuum rotary evaporation to give the powder product of CuI-Pyrphos, CuI-Mepyrphos, CuI-Mepenpyrphos or CuI-Nme2pyrphos.

The growth of CuI-Pyrphos single crystals

The excess CuI-Pyrphos powder was dispersed in the acetonitrile solvent at 50 °C to form a hot mixture. The hot mixture was immediately filtered over a polyvinylidene fluoride filter (0.22 µm) to obtain a hot solution. The thermally saturated solution was left at room temperature for 15 days and then transferred to the refrigerator with an environmental temperature of ~5 °C. After being left another 15 days without any disturbance, yellow transparent single crystals slowly formed in the bottom of the acetonitrile solution and were collected by a quick washing of ethanol.

Single-crystal X-ray diffraction

Single-crystal X-ray diffraction was performed on a Rigaku Oxford diffraction Gemini S Ultra diffractometer using Mo Kα radiation at room temperature. The data collection and processing were performed with CrysAlisPro software45. The crystal structure was solved with the SHELXS46 structure solution program using Direct Methods and refined by the SHELXL47 software package.

Theoretical calculation

To elucidate electrostatic profile of selected CuI-Pyrphos, we carried out density functional theory (DFT) calculations. We optimized the CuI-Pyrphos monomer using the PBEh-3c48 method as implemented in ORCA v.5.0.3 (ref. 49) and obtained its electrostatic potential using GAUSSIAN 09 (ref. 50). All electronic structure calculations performed in GAUSSIAN 09 employed the PBE0 functional in combination with the 6-31 G* basis set for lighter elements (C, H, N, P), and Stuttgart’s SDD pseudopotential and basis set for heavier elements (Cu, I). The frontier Kohn–Sham orbitals for the singlet ground state (S0) were visualized using the GaussView program based on the formatted checkpoint files of these two structures.

X-ray absorption spectroscopy measurements

X-ray absorption spectroscopy at the Cu K-edge (E0 = 8,979 eV) was performed at beamline BL14W1 of Shanghai Synchrotron Radiation Facility (SSRF), operating at 3.5 GeV under the ‘top-up’ mode with a constant current of 220 mA. The Cu K-edge spectra were recorded under transmission mode with two ion chambers. The white light was monochromatized by a Si(111) double-crystal monochromator. Athena and Artemis codes were used to extract and fit data. For the XANES part, the experimental absorption coefficients as a function of energies μ(E) were processed by background subtraction and normalization procedures. The normalized EXAFS spectra were obtained by subtracting the post-edge background from the overall absorption and then normalizing with respect to the edge-jump step. For the EXAFS part, the Fourier-transformed data were fitted in R space. The passive electron factor, S02, was determined by fitting the experimental copper foil data, and then fixed for further analysis of the measured samples. The parameters described the local structure environment (including coordination numbers, bond distances and Debye–Waller factors) around the absorbed atoms, and were allowed to vary during the fit process.

LED device fabrication

The device architecture comprises a multilayered structure of ITO/PEDOT:PSS (39 nm)/poly-TPD (26 nm)/PVK (28 nm)/CuI-Pyrphos (39 nm)/TmPyPB (55 nm)/LiF/Al, in which ITO and aluminium serve as anode and cathode, PEDOT:PSS and LiF as hole and electron-injecting layers, poly-TPD and PVK as hole-transport layers, and TmPyPB as the electron-transport layer. Primarily, the patterned ITO-coated glass substrate was cleaned by subsequent sonication in detergent liquids, deionized water, isopropyl alcohol, acetone and ethanol in sequence. After 15 min of UV–ozone treatment, the PEDOT:PSS solution was spun onto the surface of the ITO-coated glass substrate by a spin-coater at 3,000 r.p.m. for 50 s and baked at 140 °C on a hot plate for 30 min under ambient conditions. A solution of poly-TPD in chlorobenzene (10 mg ml−1) was spin-coated onto the PEDOT:PSS layer at 3,000 r.p.m. for 50 s, followed by thermal annealing at 130 °C for 20 min under nitrogen atmosphere. A solution of PVK in 1,4-dioxane (6 mg ml−1) was then spin-coated at 3,000 r.p.m. for 40 s and annealed at 100 °C for 10 min under nitrogen atmosphere. After that, the solution of CuI-Pyrphos powders dissolved in DMF (50 mg ml−1) was spin-coated on top of the PVK film at a speed of 5,500 r.p.m. for 50 s and annealed at 60 °C for 8 min. The host–dopant structure emissive layer was deposited by spin coating the mixed solution of bis-4-(N-carbazolyl)phenyl)phenylphosphine oxide:40% CuI-Pyrphos clusters. Finally, 30 nm TmPyPB, 1 nm LiF and 100 nm aluminium were thermally deposited under a high vacuum of ~2 × 10−4 Pa. The device active area was 4 mm2 due to the overlapping area of the ITO and aluminium electrodes. The current versus voltage characteristic of the as-fabricated LED device was recorded by a Keithley 2400 SourceMeter. The luminescence was revealed through photon flux using a silicon photodiode, which was calibrated by a PR-670 spectrum scan luminance meter. The electroluminescence spectrum was collected using an Ocean Optics JAZ spectrometer. Other important parameters used to characterize LEDs were all calculated from the L–J–V and electroluminescence measurements under the assumption that the emission of the LED exhibits a Lambertian pattern. All of the measurements were performed at room temperature without any encapsulation under nitrogen atmosphere.

Large-area LED device fabrication

The device architecture is consisted of a multilayered structure of ITO/PEDOT:PSS/poly-TPD/PVK/CuI-Pyrphos/TPBi/LiF/Al, in which ITO and aluminium serve as anode and cathode, PEDOT:PSS and LiF as hole and electron-injecting layers, poly-TPD and PVK as hole-transport layers, and TPBi as the electron-transport layer. Primarily, the patterned ITO-coated glass substrate was cleaned by subsequent sonication in detergent liquids, deionized water, isopropyl alcohol, acetone and ethanol in sequence. After treated by UV–ozone for 15 min, the PEDOT:PSS solution was spun onto the surface of the ITO-coated glass substrate by a spin-coater at 3,000 r.p.m. for 50 s and baked at 130 °C on a hot plate for 20 min under ambient conditions. A solution of poly-TPD in chlorobenzene (6 mg ml−1) was spin-coated on the PEDOT:PSS layer at 2,000 r.p.m. for 45 s, followed by thermal annealing at 150 °C for 20 min under nitrogen atmosphere. A solution of PVK in chlorobenzene (6 mg ml−1) was then spin-coated at 2,000 r.p.m. for 45 s and annealed at 120 °C for 20 min under nitrogen atmosphere. After that, the solution of CuI-Pyrphos dissolved in DMF (50 mg ml−1) was blade-coated on top of the PVK film at a speed of 30 mm s−1, and the depth of the applicator was fixed at around 2–3 μm to ensure a relatively thin CuI-Pyrphos film. The humidity and the substrate temperature during blade-coating were around 35% and 50 °C, respectively. After blade-coating, the films were immediately transferred to N2-filled glovebox and then annealed at 60 °C for 8 min. Finally, 40 nm TPBi, 1.2 nm LiF and 100 nm aluminium were thermally deposited under a high vacuum of ~2 × 10−4 Pa. The device active area was 36 cm2 due to the overlapping area of the ITO and aluminium electrodes. The electroluminescence performance of the larger-area CuI-Pyrphos LED (6 × 6 cm2) was measured by attaching the devices on top of a silicon photodiode (FDS-1010-CAL, Thorlabs). Limited by the detector area (1 × 1 cm2), our device performance results are based on assumption of uniform emission over whole large area.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. The X-ray crystallography data for CuI-Pyrphos structure have been deposited in Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre (CCDC) under accession no. CCDC-2266353. The data can be obtained free of charge from the CCDC via http://www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif.

References

Han, T.-H. et al. A roadmap for the commercialization of perovskite light emitters. Nat. Rev. Mater. 7, 757–777 (2022).

Woo, J. Y. et al. Advances in solution-processed OLEDs and their prospects for use in displays. Adv. Mater. 35, 2207454 (2023).

Jang, E. & Jang, H. Review: quantum dot light-emitting diodes. Chem. Rev. 123, 4663–4692 (2023).

Liu, X.-K. et al. Metal halide perovskites for light-emitting diodes. Nat. Mater. 20, 10–21 (2020).

Wang, S., Zhang, H., Zhang, B., Xie, Z. & Wong, W.-Y. Towards high-power-efficiency solution-processed OLEDs: material and device perspectives. Mater. Sci. Eng. R Rep. 140, 100547 (2020).

Deng, Y. et al. Solution-processed green and blue quantum-dot light-emitting diodes with eliminated charge leakage. Nat. Photon. 16, 505–511 (2022).

Min, H. et al. Additive treatment yields high-performance lead-free perovskite light-emitting diodes. Nat. Photon. 17, 755–760 (2023).

Hahm, D. et al. Direct patterning of colloidal quantum dots with adaptable dual-ligand surface. Nat. Nanotechnol. 17, 952–958 (2022).

Li, N. et al. Versatile host materials for both D-A-type and multi-resonance TADF emitters toward solution-processed OLEDs with nearly 30% EQE. Adv. Mater. 35, 2300510 (2023).

Sun, D. et al. Thermally activated delayed fluorescent dendrimers that underpin high-efficiency host-free solution-processed organic light-emitting diodes. Adv. Mater. 34, 2110344 (2022).

Won, Y.-H. et al. Highly efficient and stable InP/ZnSe/ZnS quantum dot light-emitting diodes. Nature 575, 634–638 (2019).

Kim, T. et al. Efficient and stable blue quantum dot light-emitting diode. Nature 586, 385–389 (2020).

Liu, W. et al. A family of highly efficient CuI-based lighting phosphors prepared by a systematic, bottom-up synthetic approach. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137, 9400–9408 (2015).

Zhang, X. et al. Systematic approach in designing rare-earth-free hybrid semiconductor phosphors for general lighting applications. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 14230–14236 (2014).

Troyano, J., Zamora, F. & Delgado, S. Copper(I)-iodide cluster structures as functional and processable platform materials. Chem. Soc. Rev. 50, 4606–4628 (2021).

Xie, M. et al. Highly efficient sky blue electroluminescence from ligand-activated copper iodide clusters: overcoming the limitations of cluster light-emitting diodes. Sci. Adv. 5, eaav9857 (2019).

Wang, J. J. et al. Chiral phosphine–copper iodide hybrid cluster assemblies for circularly polarized luminescence. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143, 10860–10864 (2021).

Zhu, K. et al. A new type of hybrid copper iodide as nontoxic and ultrastable LED emissive layer material. ACS Energy Lett. 6, 2565–2574 (2021).

Zhang, N. et al. Overcoming efficiency limitation of cluster light-emitting diodes with asymmetrically functionalized biphosphine Cu4I4 cubes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 6551–6557 (2022).

Volz, D. et al. Molecular construction kit for tuning solubility, stability and luminescence properties: heteroleptic MePyrPHOS–copper iodide-complexes and their application in organic light-emitting diodes. Chem. Mater. 25, 3414–3426 (2013).

Zink, D. M. et al. Heteroleptic, dinuclear copper(I) complexes for application in organic light-emitting diodes. Chem. Mater. 25, 4471–4486 (2013).

Trattnig, R. et al. Bright blue solution processed triple-layer polymer light-emitting diodes realized by thermal layer stabilization and orthogonal solvents. Adv. Funct. Mater. 23, 4897–4905 (2013).

Lee, Y. J., Park, S.-S., Kim, J. & Kim, H. Interface morphologies and interlayer diffusions in organic light emitting device by X-ray scattering. Appl. Phys. Lett. 94, 223305–223305 (2009).

Smith, A. R. et al. Diffusion-the hidden menace in organic optoelectronic devices. Adv. Mater. 24, 822–826 (2012).

Chen, J. et al. Efficient and bright white light-emitting diodes based on single-layer heterophase halide perovskites. Nat. Photon. 15, 238–244 (2020).

Chen, H. et al. Efficient and bright warm-white electroluminescence from lead-free metal halides. Nat. Commun. 12, 1421 (2021).

Heo, J.-M. et al. Bright lead-free inorganic CsSnBr3 perovskite light-emitting diodes. ACS Energy Lett. 7, 2807–2815 (2022).

Lu, J. et al. Dendritic CsSnI3 for efficient and flexible near-infrared perovskite light-emitting diodes. Adv. Mater. 33, e2104414 (2021).

Luo, J. et al. Efficient and stable emission of warm-white light from lead-free halide double perovskites. Nature 563, 541–545 (2018).

Luo, J. et al. Efficient blue light emitting diodes based on europium halide perovskites. Adv. Mater. 33, e2101903 (2021).

Ma, Z. et al. Stable yellow light-emitting devices based on ternary copper halides with broadband emissive self-trapped excitons. ACS Nano 14, 4475–4486 (2020).

Ma, Z. et al. High color-rendering index and stable white light-emitting diodes by assembling two broadband emissive self-trapped excitons. Adv. Mater. 33, e2001367 (2021).

Ma, Z. et al. Electrically-driven violet light-emitting devices based on highly stable lead-free perovskite Cs3Sb2Br9 quantum dots. ACS Energy Lett. 5, 385–394 (2019).

Seo, G. et al. Lead-free halide light-emitting diodes with external quantum efficiency exceeding 7% using host–dopant strategy. ACS Energy Lett. 6, 2584–2593 (2021).

Wang, K. et al. Lead-free organic-perovskite hybrid quantum wells for highly stable light-emitting diodes. ACS Nano 15, 6316–6325 (2021).

Yuan, F. L. et al. Color-pure red light-emitting diodes based on two-dimensional lead-free perovskites. Sci. Adv. 6, eabb0253 (2020).

Scholz, S., Kondakov, D., Lussem, B. & Leo, K. Degradation mechanisms and reactions in organic light-emitting devices. Chem. Rev. 115, 8449–8503 (2015).

Woo, S.-J., Kim, J. S. & Lee, T.-W. Characterization of stability and challenges to improve lifetime in perovskite LEDs. Nat. Photon. 15, 630–634 (2021).

Kim, J. S. et al. Ultra-bright, efficient and stable perovskite light-emitting diodes. Nature 611, 688–694 (2022).

Zink, D. M. et al. Synthesis, structure, and characterization of dinuclear copper(I) halide complexes with P^N ligands featuring exciting photoluminescence properties. Inorg. Chem. 52, 2292–2305 (2013).

Wallesch, M. et al. Towards printed organic light-emitting devices: a solution-stable, highly soluble Cu(I)-NHetPHOS. Chem. Eur. J. 22, 16400–16405 (2016).

Liu, X. K. et al. Metal halide perovskites for light-emitting diodes. Nat. Mater. 20, 10–21 (2021).

Chen, X. L. et al. A strongly greenish-blue-emitting Cu4Cl4 cluster with an efficient spin-orbit coupling (SOC): fast phosphorescence versus thermally activated delayed fluorescence. Chem. Commun. 52, 6288–6291 (2016).

Hofbeck, T., Monkowius, U. & Yersin, H. Highly efficient luminescence of Cu(I) compounds: thermally activated delayed fluorescence combined with short-lived phosphorescence. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137, 399–404 (2015).

CrysAlisPro, Rigaku Oxford Diffraction, Revision 1.171.41.110a (Rigaku Corporation, 2021).

Sheldrick, G. M. A short history of SHELX. Acta Crystallogr. A 64, 112–122 (2008).

Sheldrick, G.M. Crystal structure refinement with SHELXL. Acta Crystallogr. C Struct. Chem. 71, 3–8 (2015).

Grimme, S., Brandenburg, J. G., Bannwarth, C. & Hansen, A. Consistent structures and interactions by density functional theory with small atomic orbital basis sets. J. Chem. Phys. 143, 054107 (2015).

Neese, F. Software update: the ORCA program system—version 5.0. WIREs Comput. Mol. Sci. 12, e1606 (2022).

Gaussian 09 Revision D.01 (Gaussian, Inc., 2013).

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the financial support from the National Key Research and Development Program of China (grant no. 2022YFA1204800 to H.-B.Y.), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant nos. 22325505, 52073271, 22161142004 to H.-B.Y.; 62175226, 62234004 to Z.X.; and 52272167 to F.F.), the USTC Research Funds of the Double First-Class Initiative (grant no. YD2060002034 to H.-B.Y.), the Collaborative Innovation Program of Hefei Science Center, CAS (grant no. 2022HSC-CIP018 to H.-B.Y.) and Innovation Program for Quantum Science and Technology (grant no.2021ZD0301603 to F.F.). We thank J. Wang for helping us collect in situ PL/UV spectra and X. Chen for helping us test temperature dependent PLQY. We thank the support from the USTC Center for Micro and Nanoscale Research and Fabrication. We also thank the support from the USTC Supercomputing Center the computing resource and the National Synchrotron Radiation Laboratory (NSRL) in Hefei.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.-B.Y. and J.-J.W. conceived the idea, designed the experiment, and analysed the data. J.-J.W. and L.-Z.F. synthesized the materials, performed characterizations and analysed the data. G.S., J.-N.Y. and Z.X. participated in the fabrication of LED devices and performed the performance tests. Y.-D.Z. and X.-S.Z. performed the XAS characterizations and analysed the data. H.X. and F.F. conducted the optical simulation for theoretical limit on outcoupling efficiency and maximum EQE. K.-H.S. and T.C. performed TEM and AFM characterizations and discussed the results. G.Z. performed DFT and TDDFT calculations and analysed the computational results. J.-J.W., L.-Z.F., G.S., J.-N.Y., G.Z. and H.-B.Y. co-wrote the manuscript. H.-B.Y. directed and supervised the project. All authors contributed to discussions and finalizing the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Photonics thanks Yizheng Jin, Tae-Woo Lee and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figs. 1–21, Tables 1–5, references and experimental section.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, JJ., Feng, LZ., Shi, G. et al. High efficiency warm-white light-emitting diodes based on copper–iodide clusters. Nat. Photon. 18, 200–206 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41566-023-01340-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41566-023-01340-8

This article is cited by

-

Efficient solution-processed light-emitting diodes based on organic-inorganic hybrid antimony halides

Nature Communications (2026)

-

Flexible light-emitting diodes with EQE approaching 26.4% from horizontal dipole-oriented metal nanoclusters

Nature Communications (2026)

-

Dual interfacial H-bonding-enhanced deep-blue hybrid copper–iodide LEDs

Nature (2025)

-

Sequential addition of cations increases photoluminescence quantum yield of metal nanoclusters near unity

Nature Communications (2025)

-

Highly efficient deep-blue LED devices made using hybrid copper–iodide compound

Nature (2025)