Abstract

Addressing the role of quantum coherence in the interplay between the different matter constituents (electrons, phonons and spin) is a critical step towards understanding transition metal oxides and designing complex materials with new functionalities. Here we use coherent vibrational control of on-site d–d electronic transitions in a model edge-sharing insulating transition metal oxide (CuGeO3) to single out the effects of vibrational coherence in electron–phonon coupling. By comparing time-domain experiments based on high- and low-photon-energy ultrashort laser excitation pulses with a fully quantum description of phonon-assisted absorption, we could distinguish the processes associated with incoherent thermal lattice fluctuations from those driven by the coherent motion of the atoms. In particular, while thermal fluctuations of the phonon bath uniformly increase the electronic absorption, the resonant excitation of phonon modes also results in light-induced transparency that is coherently controlled by the vibrational motion.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

The non-trivial interplay between high-energy electronic transitions, both on-site and charge transfer, with low-energy lattice or magnetic excitations gives rise to the rich phase diagrams of transition metal oxides1,2. Unveiling the details of this reciprocal action among the different degrees of freedom is the key to achieving a better and more reliable description and design of material properties. We stress that the coherent interaction between different excitations may be of relevance in determining the effectiveness of such interplay and that the incoherent energy exchange rate may not provide a complete physical picture of the coupling between the electrons and the phonons (or magnons). The role that the coherences of low-energy excitations play in determining macroscopic material properties is often elusive and addressed indirectly through population dynamics of high-energy excitations interacting with low-energy modes.

In time-domain studies, electron–phonon coupling is often addressed indirectly by inferring the strength of the coupling from the relaxation dynamics following a sudden photoinjection of electronic energy via high-photon-energy pulses3. The measurements of the different timescales for redistributing the excess electronic energy to other degrees of freedom are commonly interpreted through multi-temperature models, which consider the different excitations as interdependent statistical ensembles and allow for the extraction of the incoherent energy exchange among them4. In this setting vibrational and magnetic coherences can be studied only in cases subject mainly to two strong limitations: the sudden photoexcitation should be able to trigger a coherent vibrational (or magnetic) response, and the interaction between the probe and the material ‘prepared’ in a coherent vibrational state should map such coherence into photonic observables. The resonant excitation of vibrational modes (commonly dubbed ‘phonon pump’) partially lifts these limitations as the creation of the coherent lattice response is driven directly by the electromagnetic field of the laser pulse and not mediated by electron relaxation5,6,7. Contrary to what happens in standard high-photon-energy pump and probe measurements, mid-infrared (mid-IR) excitation drives a large-amplitude, low-frequency vibrational response through the resonant excitation of phonon-polariton modes. Under this condition, a coherent vibrational excitation is prepared in the electronic ground state of the material, providing the means to dynamically control the atomic position in matter8.

Here we use resonant vibrational excitation to coherently control the crystal field surrounding the Cu ions in a model compound for edge-sharing cuprate. In the following we explain the rationale of our work that is also illustrated by Fig. 1. The mid-IR excitation resonantly excites a large amplitude motion of the ions mainly along an IR-active mode. The anharmonic coupling of the excited IR-phonon to other vibrational modes results in a coherent contraction and expansion of the Cu–O bonds, within the octahedra, which coherently control the absorption in the visible region due to on-site optical transitions between crystal field levels. In detail, the resonant excitation of IR-active phonon modes results in a coherent vibrational motion of the apical oxygen that dynamically controls the energy and oscillator strength of the orbital transition between different crystal levels on Cu2+ ions. A density functional theory (DFT) estimation of the anharmonic coupling was carried out and the effective force field acting on the apical oxygen is depicted in Fig. 1c (for more details see ‘DFT calculation’ in Supplementary Information).

a, The coupling of on-site transitions between the different orbital states of Cu2+ to low-energy phonons in the ground state is indicated by the temperature-dependent static absorbance (inset, data from ref. 13) that consists of three main features associated with electronic transitions from the electronic ground-state orbital \(d_{x^2 - y^2}\) to the excited states dxy (1.55 eV), dxz, dyz (1.70 eV) and \(d_{z^2}\) (1.88 eV) whose oscillator strength increases with temperature. b, In our experiment, a mid-IR pump pulse excites vibrational modes that displace, through nonlinear phononic couplings, the atomic positions along the normal coordinate axis Q (Bt in the model). The resulting lattice distortion couples to the electronic wavefunction and induces oscillator strength variations of the Cu on-site d–d orbital transitions that are probed, after a delay δτ, by a visible pulse whose central energy is tuned across the d–d transition energies. c, DFT estimate of the force field (ΔFfield, red arrows) induced by the anharmonic response on the CuGeO3 lattice (details in the Supplementary Information).

The coherent vibrational control of the electronic transition is evidenced by the striking contrast between the results of time-domain experiments based on high-photon-energy pumps9 and mid-IR excitation. While high-photon-energy excitation results in thermal disorder that uniformly increases the absorption of crystal field levels10,11, our experiments based on mid-IR pumps reveal a transient response characterized by regions of induced transparency that can be rationalized if the electronic transitions are dynamically controlled by vibrational coherence in the electronic ground state. To disentangle the contributions to crystal field absorption that result from coherent and thermal motion of the ions, we developed a fully quantum description of dynamical phonon-mediated crystal field excitations. We use the temperature-dependent equilibrium absorption to benchmark the role of thermal fluctuations in the absorption process and extract a quantitative description of coherent versus incoherent vibrational responses. We stress that our methodology allows to distinguish the contributions to the absorption of crystal field levels that are associated with the coherent motion of the ions from those contributions driven by the incoherent thermal fluctuations.

The measurements are performed in a model system for an edge-sharing cuprate, insulating CuGeO3. This sample is ideal for two main reasons: (1) the phonons are long lived, allowing therefore for a selective excitation of vibrational modes, and (2) the three d–d electronic transitions at high energy (around 1.70 eV) are isolated from other spectral features such as the charge transfer edge12 (see ‘CuGeO3 optical properties’ in Supplementary Information). The relevant structural unit for our discussion is a CuO6 complex, with the copper atom surrounded by six oxygens at the vertices of a distorted octahedron. The three observed optical absorptions (inset in Fig. 1a) are due to on-site electronic transitions between the different d orbitals of copper whose degeneracy is removed by the broken octahedral symmetry. In particular, the three transitions observed are transitions from the ground state (\(d_{x^2 - y^2}\)) to the in-plane dxy orbital and out-of-plane dxz, dyz and \(d_{z^2}\) orbitals.

Importantly, these optical transitions are phonon-assisted. The on-site optical transition between orbitals of d symmetries should be forbidden in centrosymmetric crystals due to dipole selection rules, nevertheless, they are visible in absorption spectroscopy even at very low temperatures (<10 K)13,14. This can be understood by considering that the optical on-site d–d transitions are accompanied by the creation (and annihilation) of phonons that break the symmetry of the orbital transition, thereby removing the optical selection rules13,14,15. The involvement of a ground-state phonon mode in the optical absorption process is confirmed by the observed strong increase of the oscillator strength with temperature13,14.

We describe the transient coherent response in terms of an effective model for the phonon-mediated on-site absorption where we describe the d–d transition by means of a two-level system interacting with a vibrational mode represented by a quantum harmonic oscillator16. We choose this minimal model based on only one electronic transition and one phonon mode, because it is simple enough and allows us to treat the electric field pulse with a full quantum formalism. We will show that this simple model contains the relevant features to grasp the basic physical mechanism of vibrational coherent and incoherent (thermal) control of d–d absorption. The material effective Hamiltonian is chosen of the form:

where b (and b†) are bosonic operators for the phonon mode (of energy ω, the reduced Planck constant ℏ = 1), d (and d†) are fermionic operators describing the on-site d–d electronic transition (of energy \({\it{\epsilon }}\)) and the last term describes the interaction between the electronic and phononic degrees of freedom involved in the d–d transition, the electrons being represented by their population and the phonons by their displacement (with coupling strength M). In particular, this Hamiltonian accounts for the fact that the equilibrium position of the lattice in the electronic excited state is shifted with respect to the equilibrium position in the ground state. To describe the coherent and incoherent vibrational dressing of an on-site crystal field transition, we can consider the perturbative interaction between an external electric field and the on-site d–d transition coupled to low-energy phonons using the following interaction Hamiltonian:

where the bosonic operators ak and \(a_k^\dagger\) describe the electric field operators at frequency νk interacting with the sample and μ0 is the coupling constant. The electric field operator can be used to describe an incoherent field as in a linear response or the spectral components of a probe pulse in time-domain experiments. With this model we can retrieve the total absorption of phonon-assisted d–d transitions at equilibrium that depends on the temperature of the system as revealed by equilibrium absorption measurements of CuGeO3 at different temperatures13,14 (see the Supplementary Information for the analytical derivation of the temperature dependence, Supplementary equation (14)17). Importantly, our formalism also describes the non-zero absorption at T = 0 K and validates the phonon-assisted character of the three d–d transitions observed in optical spectroscopy (Fig. 1). Moreover, by treating the light quantum mechanically, we are able to compute explicitly the frequency-resolved absorption profile when the pump-induced phonon coherence is present.

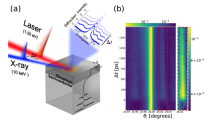

Therefore, the experimental investigation of this mechanism consists in using a mid-IR pulse to excite a phonon mode that drives a displacement of the ionic structure. This in turn modifies the interaction energy between the lattice and the orbital degrees of freedom that are then investigated by a visible probe pulse. Since on-site d–d electronic transitions in CuGeO3 have different symmetries, the expected ultrafast variations of their oscillator strength and central energy are determined by the structural changes induced by the phonon pump. To reveal these effects, we developed an optical set-up that produces mid-IR pump pulses (tunable from 5 µm to 18 µm) coupled with visible probe pulses (∼30 fs and tunable from 650 nm, 1.91 eV, to 950 nm, 1.30 eV). The detection is made by a low-noise balanced photodiode coupled to a fast digitizer system that measures the transient intensity of the probe transmitted through the mid-IR-excited CuGeO3 single crystal fixed in a cryostat kept at 8 K. All polarizations were oriented along the c axis of CuGeO3, which is the direction of the CuO6 octahedron chain (see ‘Experimental details’ in Supplementary Information).

The pump wavelength dependence of the transient transmissivity is reported in Fig. 2a (left panel) for a probe energy matching the centre of the d–d band (EVIS ≈ 1.75 eV). Similarly to previous studies10,11, we observe that the change in transmission is negative, indicating that the d–d transition oscillator strength increases following the photoexcitation. Two different regimes in the transient transmissivity can be distinguished: a broadband fast one and a slow one, whose rise time is about several picoseconds, and is visible only for specific pump wavelengths (around λpump ≈ 7.7 µm and λpump ≈ 11 μm). The slow picosecond dynamics can be understood as a thermal response of the material, which is maximized at pump wavelengths where the linear absorption is maximum (right panel of Fig. 2a). This long-timescale behaviour is present as long as the probe energy lies inside the d–d band. However, as it is shown in Fig. 2c, when the probe photon energy is on the edge of the d–d band, these dissipative dynamics disappear and only the fast response remains. Such a short-timescale behaviour is instead associated with the nonlinear coherent phonon dynamics excited by the mid-IR driving pulse. Note that the effect is maximized at frequencies (λpump ≈ 9 µm) higher than any linear dissipative absorption of the phonon modes12,18. However, pump–probe penetration depth mismatch, propagation effects and multi-phonon absorption may play a role in determining the optimal pumping wavelength8 (see ‘Pump wavelength dependency’ in Supplementary Information). The direct excitation of vibrational modes drives large-amplitude ionic displacements that trigger a nonlinear phononic response: the driven IR-active modes couple to Raman-active excitations that results in a transient deformation of the crystal lattice along the Raman coordinates (for a description of the nonlinear phononic coupling of type QIR2QRaman, see ‘Anharmonic coupling’ in Methods).

a,c, Pump wavelength dependency of the transmissivity measured for a probe energy EVIS = 1.75 eV (a) and 1.37 eV (c). The long-timescale signals, at λmidIR ≈ 7.7 µm and λmidIR ≈ 11 µm, are associated with a dissipative thermal response12,18 and overlap with the minima of CuGeO3 transmission (right panel of a, data reproduced from ref. 12). b, Time-dependent transmissivity as a function of the probe photon energy for λmidIR = 9 µm pump wavelength. The bottom panel displays time-dependent transmissivity at energies of 1.37 eV, 1.55 eV, 1.70 eV and 1.89 eV (highlighted respectively by the red, orange, green and purple dashed lines in the map). The lowest energy is in the tail of the d–d absorption and the others correspond to the central energies of the d–d bands (right panel, data reproduced from ref. 14). Transparency regions are observed at 1.55 eV in the first 50 fs and below 1.4 eV on longer timescales. d, Fitted map (left) obtained with the transient Gaussian fitting parameters (Δp) of the three d–d absorption peaks (right): amplitude (Ai), central energy (Ei) and bandwidth (σi), and background (BG). The time dependence of the parameters highlights the coherent nature of the fast time evolution of d–d phonon-assisted transitions.

To disentangle the coherent from the incoherent phononic dressing of the d–d electronic transitions of CuGeO3, we measured the probe transient transmissivity as a function of the probe photon energy, by keeping λpump centred at 9 µm and the sample at a base temperature T = 8 K, where thermal broadening effects of the d–d bands are minimized (see ‘Thermal effects’ in Supplementary Information for measurements at 300 K). The measured response, displayed in the main panel of Fig. 2b, reveals for short timescales a very different transient response for different probe photon energies, as is better shown by the line cuts at probe energies of 1.37 eV, 1.55 eV, 1.70 eV and 1.89 eV (bottom panel). On longer timescales, the signal is very weak but it shows an oscillatory behaviour that can be associated with an Ag mode at 187 cm−1 and further validates the nonlinear phononic couplings previously mentioned (see ‘Phonon mode on long timescale’ in Supplementary Information).

We will focus on the 0 to 500 fs range. On short timescales, we can observe three probe energy ranges giving rise to different time-domain responses. For a probe energy below 1.45 eV, the transient transmissivity is negative in the delay range 0 fs to 300 fs, while it changes sign after a delay time of 300 fs and remains positive up to 500 fs. On the contrary for probes at 1.45 eV to 1.75 eV, the transient transmissivity is at first positive and subsequently drops to negative values. Moreover, in that area, two energy substructures are visible around 1.5 eV and 1.7 eV. For a probe energy greater than 1.75 eV, the transient transmissivity is fully negative and it shows an uncommon temporal structure where the decreasing slope is longer (about 350 fs) than the following rising edge (about 150 fs), indicative of the fact that the ultrafast response has a coherent nature. The photon energy dependence of the probe response is representative of the position of the three d–d transitions for which central energies are around 1.5 eV for \(d_{x^2 - y^2}\to d_{xy}\), 1.7 eV for \(d_{x^2 - y^2}\to d_{xz},\,d_{yz}\) and 1.9 eV for \(d_{x^2 - y^2} \to d_{z^2}\) (refs. 13,19). The equilibrium and transient response of the oscillators can be quantified by means of a fit with three Gaussians representing the three d–d transitions. We use a differential fit to extract quantitatively the time-domain changes in the amplitudes, width and central energy of the d–d bands with respect to equilibrium values (details in ‘Analysis’ in Supplementary Information). The results of the fit are reported in Fig. 2d for direct comparison with the data in Fig. 2b. Note that the transparency regions cannot be obtained in the differential fit without time-dependent changes of the central energy and width of the lowest-energy d–d transition (\(d_{x^2 - y^2} \to d_{xy}\)). Altogether this means that the mid-IR excitation coherently controls the electronic properties of the d–d bands.

To describe coherent and incoherent contributions to the time-domain response of on-site d–d transitions we consider the initial vibrational state (before the probe arrives) as a thermal phonon state. The equilibrium case showing the manifold of possible transitions is illustrated in Fig. 3a. In this effective language, resonant excitation of the vibrational IR mode that is nonlinearly coupled to the relevant octahedral vibration controlling d–d transitions is caused by a displacement operator, \(D = {\mathrm{e}}^{B_tb^\dagger - B_tb}\), acting on an initial thermal vibrational state. The total absorption (computation detailed in ‘Theory’ in Supplementary Information) reads:

where Bt corresponds to the time-dependent displacement along the phonon normal mode of energy ω, μ0 is the oscillator strength and β is the inverse temperature (1/kBT), where kB is the Boltzmann constant. Note that this result is consistent with the empirical description given in ref. 14 for the temperature-dependent d–d band absorption measured.

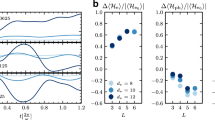

a, Illustration of the model. The transitions between the ground state and the excited state of energy εd (computed through the Hamiltonian of equation (1)) are mediated by the interaction Hamiltonian (equation (2)) that gives rise to different quantum paths accompanied by the creation of ℓ phonons of energy ω0. The absorption intensities Γℓ (top right) at energies εd + ℓω0 are determined by the interferences between these quantum paths together with the initial thermal population of the ground state (bottom right). Some of the interfering paths for \(\varGamma _\ell ^{{\mathrm{eq}}}\) at ℓ = −1, 0, +1 have been highlighted in yellow, cyan and green for clarity. b, Temperature dependence of the total optical absorption associated with the on-site d–d transitions. The absorption data (crosses) are taken from ref. 14. The ground-state distortion (Bt,eq) revealed by our full quantum model (equation (3)) gives a temperature dependence of the oscillator strength (solid line) in good agreement with the experimental data (the dashed curve corresponds to the temperature-dependant absorption behaviour obtained by a standard model including solely phonon coupling but no feedback on the atomic positions). The inset shows the equilibrium absorption profile for three different temperatures and the Gaussian dashed curves are a guide to the eye for the expected d–d absorption derived in this framework. c, The variation of the absorption spectral line distribution (\(\varGamma _\ell ^{{\mathrm{disp}}} - \varGamma _\ell ^{{\mathrm{eq}}}\)) for four normal displacements at different times indicates that the coherent vibrational motion can coherently control on-site d–d electronic transitions in the visible range (bottom panel in grey represents the equilibrium distribution).

As reported in Fig. 3b, our model accounts for all contributions to the equilibrium d–d absorption including both thermal and quantum fluctuations of the atomic positions and identifies the frequency of the phonon mediating the coupling to be ω = 131 cm−1, with a corresponding equilibrium displacement Bt,eq = 0.62 (in arbitrary units). We point out that the extracted values take into account the overall d–d band absorption, which is not representative of a single transition, and that we limited our description to one phonon mode leading possibly to an overestimated Bt,eq (Supplementary Fig. 10). To tune our model parameters, we can compare the computed equilibrium absorption as a function of the temperature (inset of Fig. 3b). Note that the discrete spectral lines are expected in the case of a molecular system, while, in the solid-state context, the lineshape will be smeared out by the presence of a non-flat band structure, inhomogeneous and homogeneous broadening. In agreement with the experimental observation, the model shows that an increase of the temperature mostly increases all the discrete transition probabilities that leads to a global increase of absorption.

Interestingly, the time dependence of the atomic position (Bt) produced by the mid-IR excitation and the phonon nonlinear coupling leads to a different behaviour for the phonon-assisted absorption probabilities Γℓ (computation detailed in ‘Theory’ in Supplementary Information), where the parameter ℓ is the electronic transition accompanied by the production of ℓ phonons. In Fig. 3c, we display the variations of the transition probability with respect to the equilibrium distribution (\(\varGamma _\ell ^{{\mathrm{disp}}} - \varGamma _\ell ^{{\mathrm{eq}}}\)) in the case of four distinct displacements away from the equilibrium position. These profiles represent the changes in absorption induced by coherent vibrational motion at different times and show that the absorption central frequency can be shifted up or down in energy, which results in regions of vibrationally controlled transparency, as observed in experiments. A quanlitative agreement of the central frequency and energy–bandwidth dynamics of the absorption line profile can be extracted from the first and second momentum of the distribution20. Elastic displacements ∆Bt of the order of 10−3, which is equivalent to real atomic displacements of approximately 10−4 Å, result in changes of the central frequency of the electronic absorption of about ∆E ≈ 60 μeV and bandwidth ∆σ ≈ 18 μeV (Supplementary Information).

The paradigm of most of the pump and probe studies is to photoexcite at high frequency and to consider an energy flow from electrons to phonons. The example of CuGeO3 is emblematic in this respect. In standard photodoping experiments the excess of electronic energy injected by the pump is quickly redistributed (few tens of femtoseconds) toward phonon modes and it induces a global heating of the system. This leads to an increased disorder that results in strengthening the phonon-assisted crystal field absorption10,11 (equation (3) and Fig. 3b)).

The coupling processes between electrons and phonons are often described by an effective coupling between electrons and a bath of phonons that is kept in thermal equilibrium. In this condition, the coupling between the material and the electromagnetic field is described by Fermi’s golden rule where the absorption cross-section is obtained by a dipole operator connecting two eigenstates of the system with definite electronic and phononic excitations. Importantly, the non-equilibrium evolution is normally described by a simple extension of this approach, dubbed multi-temperature model, where the temperature of phonons and electrons is allowed to change independently in time. This accounts for a large part of our experiments because any injection of energy should increase the phononic temperature and its disorder, enhancing the dipole-forbidden d–d transition probabilities.

Nevertheless, we stress that any effective-temperature approach will fail in describing the coherent response observed when pumping low-energy degrees of freedom with the mid-IR pulse and probing electronic d–d transitions in the visible frequency range. The coherent control of transmissivity at short timescales (<500 fs) revealed a complex probe energy dependency (Fig. 2b). In particular, the \(d_{x^2 - y^2}\to d_{z^2}\) transition is continuously made more absorptive by the mid-IR excitation and quickly recovers the equilibrium value when the exciting field is gone. More interestingly, both transitions \(d_{x^2 - y^2}\to d_{xy}\) and \(d_{x^2 - y^2}\to d_{xz},d_{yz}\) show a transient transparency at short times that cannot be described by an increase of the phonon temperature and indicate a coherent vibrational control of the electronic transition probabilities.

The optical absorption dynamics is the result of coherent lattice distortion along different phonon modes of the system. Our model explains this fact as the result of a displacement of the ions in the electronic ground state along a direction coupled to the electronic transition, which could not be described by standard multi-temperature models but requires a full treatment of the coherences of the low-energy degrees of freedom. The dissipative dynamics of the coherent response observed for short timescales (<500 fs) that relaxes into an incoherent quasi-thermal response at longer times is determined by the details of the dissipation properties of the material. These will result from the coupling of the modes relevant for the vibrational coherent control of d–d transitions to other degrees of freedom in the material that cannot be described by the minimal model proposed here and will be the subject of future studies.

In summary, we have demonstrated that vibrational pumping can be used to coherently control optical transitions of electronic origin. The mid-IR excitation of IR-active phonon modes, together with a strong lattice anharmonicity, can be used to dynamically control the position (and momentum) of the atoms that in turn modifies the crystal field electronic transition in a model system for transition metal oxides. The experimental evidence of light-induced transparency controlled by the coherent vibrational motion, supported by a minimal theoretical model, provides the means to measure electron–phonon coupling in complex materials with phase sensitivity with respect to the vibrational motion, that is, beyond the population-driven incoherent coupling description. In the context of superconductivity, our approach, which could be extended to more complex Hamiltonian interactions, may provide a guideline to experimentally address the gap between the Bardeen–Cooper–Schrieffer theory (BCS), with non-local and instantaneous interactions, and Eliashberg approaches that are local in space and retarded in time. The possibility of driving coherent vibrational excitations and to control local electronic degrees of freedom may provide the means to address the coherent versus incoherent contributions to the interactions between electrons and phonons (or spins21,22,23,24) and to address directly the delay in the development of the overscreening of Coulomb repulsion that is at the core of most of the quantum coherent phases observed in transition metal oxides.

Methods

Experimental method

The experiment was performed on our recently developed mid-IR pump and visible probe set-up operating up to a repetition rate of 50 kHz (more details can be found in refs. 25,26). The mid-IR pulses were generated by difference-frequency generation between the output of a twin optical parameric amplifier (ORPHEUS-Twin, Light Conversion). The pump central wavelength can be tuned from 4 µm up to 18 µm. The pump pulses were then focused on the sample with a spot size of about 150 ± 50 µm diameter, which allows to reach fluences up to few mJ cm−2. The probe pulses were produced with a non-collinear optical parameric amplifier (ORPHEUS-N, Light Conversion) that generates visible probe pulses whose central wavelength is tunable from 650 nm (1.91 eV) up to 950 nm (1.30 eV) keeping a bandwidth of about 60 ± 10 meV, which corresponds to a Fourier-transform-limited pulse duration shorter of 30 fs (checked with frequency-resolved optical gating27). The probe beam goes towards a delay line and a 90/10 beamsplitter to obtain a reference probe beam (10%) and a main part (90%) that goes through an achromatic half-wave plate followed by a polarizer, to control its power. The main part is then focused on a spot size of about 75 ± 25 µm diameter. A probe excitation density smaller than 2 µJ cm−2 was chosen. Pump and probe pulses interact in a non-collinear scheme (angle < 15°) on the CuGeO3 sample (100 µm thick) that is inside an ultra-low-vibration closed-cycle cryostat (CS204-DMX20-OM, Advanced Research Systems) mounted on a three-axis positioning stage. Moreover, both pump and probe beams have a vertical polarization. For each delay step, we measured the transmitted probe beam with one channel of the balanced photodiode detector and the other channel was used to measure the reference probe beam. The transmissivity (∆T/T) measurements were carried out by subtracting the reference probe beam signal from the sample-transmitted signal to remove the intensity fluctuations of the laser. Then, the differential signal was processed by a lock-in amplifier, in phase with an optical chopper wheel (500 Hz) located on the pump arm. The set-up is sensitive to transmissivity variation as small as 10−5.

Analysis

We performed a fit of the transmissivity map in the energy domain and we repeated this fit for each time delay. To obtain a set of initial parameters, we firstly fitted the linear optical absorption of the d–d transitions (measured in ref. 14) by a set of three Gaussians plus a background (Fig. 1a):

where \(A_i^0\), \(E_i^0\) and \(\sigma _i^0\), respectively, correspond to the amplitude, central energy and bandwidth of the Gaussian representing the ith d–d transition, and BG accounts for the background absorption. Based on the equilibrium fit we defined a fitting function for the transient transmissivity map as:

where τ is the pump–probe delay and Γfit(τ,E) is the total absorption where each Gaussian parameter (Ai, Ei or σi) can be free to change or not. We tested several combinations of free parameters with the aim to find the best compromise of (1) obtaining a good fitted map (done by letting all the parameters be free) and (2) using a minimum number of free parameters. The minimal set of parameters allowing for a good quality fit included the three amplitudes (Ai(τ)), the central energy and bandwidth of the first d–d transition (Ei(τ), σi(τ)) and the background BG(τ)) to be free in order to obtain a good agreement with the measured map (Supplementary Information).

Fully quantum model

The calculation details of the theoretical model are explained in the Supplementary Information and here is a summary of the main steps. We describe the localized d–d transition by means of a two-level system interacting with a single vibrational mode of the crystal represented by a quantum harmonic oscillator (H, equation (1)). Our theoretical model assumes the electronic transitions to be induced by the interaction of the sample electronic and phononic degrees of freedom with the probe light. For a fully quantum picture, we have chosen a dipolar electron–phonon–photon interaction (Hint, equation (2)) that allows us to compute the average number of transmitted photons at a certain frequency, up to leading order in perturbation theory. This, in turn, gives information about the absorption spectrum of the sample in the frequency range pertaining to the electronic degrees of freedom, which, for sake of simplicity, have been restricted to a single dressed electronic transition. The theoretical expressions for the relevant quantities are derived by taking into account the phonon displacement induced by the pump pulse. The expected temperature dependence of the absorption profile (\({{\varGamma }}_{{\mathrm{tot}}}^{{\mathrm{displaced}}}\), equation (3)), consistent with the experimental findings14, is correctly predicted by our model. Finally, we can compute the spectral lines, namely the phonon-assisted absorption probabilities, Γℓ, where the parameter ℓ refers to an electronic transition accompanied by the production of ℓ phonons. They are defined by:

where \(D = {\mathrm{e}}^{B_t\left( {b^\dagger - b} \right)}\) is a phononic displacement operator sending b into b–Bt, with Bt a time-modulated real parameter, ρβ is the thermal state for the vibrational degree of freedom at inverse temperature β, and \(\left| n \right\rangle\) are the Fock states with n vibrational excitations. The analytic computation of each Γℓ is non-trivial (see the Supplementary Information for details) and leads to:

where we defined the three adimensional parameters A, \(\widetilde {B_t}\), C as:

These three parameters completely specify the model in the approximation we used. The parameter A quantifies the phonon–electron coupling and therefore the displacement of the nuclear positions in the electronic excited state. The parameter \(\widetilde {B_t}\) instead is a dynamical one, originated by the pump pulse, and given by the ratio between the light-induced instantaneous displacement and the displacement due only to the electron–phonon coupling. The third parameter, C, specifies the temperature in units of the phonon frequency. By choosing these parameters correctly, we can predict a shift of the central frequency (that is, energy) of the transmitted photon distribution.

Anharmonic coupling

Oscillations in the transmissivity map are observed at long timescales at the frequency of the low-energy Raman-active Ag mode (187 cm−1)18. However, given the pump frequency (around 9 µm) and polarization (along the c axis), the mostly coupled phonon mode should be the high-frequency IR-active mode B2u (720 cm−1). The observed phenomenology can be explained by means of anharmonic coupling between the high-frequency IR-active mode and the low-frequency Raman-active mode as given by the following Hamiltonian5:

where A is some anharmonic coupling constant, N is the number of cells in the lattice, QIR is the coordinate of the IR-active mode and QRS is the coordinate of the Raman-active mode. As a consequence, the equation of motion for the coordinate QRS reads

where ΩRS is the frequency of the Raman mode, so that the fast oscillation of the high-energy mode acts as a force field for the low-frequency mode. In particular, the pump field induces the following evolution of the IR-active-mode coordinate

where F(τ) is the pulse envelope, E0 is the electric field amplitude, ΩIR is the frequency, MIR is the reduced mass and e* is the effective charge. Therefore, the coordinate QRS evolves in time as

Assuming a much longer lifetime for the low-frequency phonon mode, we can explain the long-lived oscillations of transmissivity at the frequency ΩRS.

DFT calculations

The structure optimization was performed using the dedicated software QUANTUM ESPRESSO (QE)28. The lattice parameters were taken from the literature18 and the initial data for the atomic positions inside the unit cell were taken from the Materials Project website https://materialsproject.org/materials/mp-21344. We used the PBE functional29 and PSEUDODOJO pseudopotentials30 generated with the same functional. As a first step, we reproduced the known results for the ground-state properties of CuGeO3 (ref. 31). In particular, as discussed in ref. 31, we verified that standard DFT calculations fail to predict the insulating bandgap of this material and a more refined treatment is needed. We used a spin-polarized calculation with a Hubbard correction DFTS+U32. We performed the calculation with both QE and octopus33,34, another DFT dedicated software. The obtained band structures are compatible and in turn they are in agreement with the result presented in ref. 31 (see ‘DFT calculations’ in Supplementary Information).

The calculation of the phonon modes was performed with the software QE. The diagonalization of the dynamical matrix was performed without the Hubbard correction because this function is currently not available in the software (results are in Supplementary Table 1). After the structure relaxation, there are still two negative eigenvalues, however, this is consistent with the uncertainty of around 40 cm−1 that can be estimated by comparing the theoretical result with the fit of experimental data18. We are mostly interested in the high-frequency sector of the spectrum, in particular in the IR-active mode B2u (702 cm−1), which is a linear combination of the x coordinates (equivalent to the c axis in our case) of the 10 atoms in the unit cell. Therefore, this mode should be the mostly excited with a pump polarized along the c axis as it is the highest frequency among the modes with the right symmetry. To estimate the anharmonic effects on the perturbation of the octahedron we displaced the atoms along the normal mode B2u and computed the force field resulting on each atom for a positive displacement (+∆x) and for a negative displacement (−∆x). The remaining force field, which is computed by the sum of the force fields for opposite displacements, is depicted in Fig. 1c and it shows that the apical oxygen atoms are forced to move along the y direction (see Supplementary Table 2 for values).

Data availability

Source data are provided with this paper. All other data that support the plots within this paper and other findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Dagotto, E. Complexity in strongly correlated electronic systems. Science 309, 257–262 (2005).

Zaanen, J., Sawatzky, G. A. & Allen, J. W. Band gaps and electronic structure of transition-metal compounds. Phys. Rev. Lett. 55, 418–421 (1985).

Conte, S. D. et al. Disentangling the electronic and phononic glue in a high-Tc superconductor. Science 335, 1600–1603 (2012).

Allen, P. B. Theory of thermal relaxation of electrons in metals. Phys. Rev. Lett. 59, 1460–1463 (1987).

Först, M. et al. Nonlinear phononics as an ultrafast route to lattice control. Nat. Phys. 7, 854–856 (2011).

Mankowsky, R. et al. Nonlinear lattice dynamics as a basis for enhanced superconductivity in YBa2Cu3O6.5. Nature 516, 71–73 (2014).

Mankowsky, R., Först, M. & Cavalleri, A. Non-equilibrium control of complex solids by nonlinear phononics. Rep. Prog. Phys. 79, 064503 (2016).

Cartella, A., Nova, T. F., Fechner, M., Merlin, R. & Cavalleri, A. Parametric amplification of optical phonons. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 115, 12148–12151 (2018).

Giannetti, C. et al. Ultrafast optical spectroscopy of strongly correlated materials and high-temperature superconductors: a non-equilibrium approach. Adv. Phys. 65, 58–238 (2016).

Giannetti, C. et al. Disentangling thermal and nonthermal excited states in a charge-transfer insulator by time- and frequency-resolved pump-probe spectroscopy. Phys. Rev. B 80, 235129 (2009).

Yuasa, Y., Nakajima, M., Yamanouchi, T., Ueda, Y. & Suemoto, T. Ultrafast time-resolved spectroscopy of the spin-Peierls compound CuGeO3. J. Lumin. 128, 1087–1089 (2008).

Damascelli, A., Marel, D. V. D., Dhalenne, G. & Revcolevschi, A. Optical spectroscopy of pure and doped CuGeO3. Phys. Rev. B 61, 12063–12074 (2000).

Bassi, M. et al. Optical absorption of CuGeO3. Phys. Rev. B 54, R11030–R11033 (1996).

O’Neal, K. R. et al. Vibronic coupling and band gap trends in CuGeO3 nanorods. Phys. Rev. B 96, 075437 (2017).

Monney, C. et al. Determining the short-range spin correlations in the spin-chain Li2CuO2 and CuGeO3 compounds using resonant inelastic X-ray scattering. Phys. Rev. Lett. 110, 087403 (2013).

Mahan, G. D. Many-Particle Physics (Springer, 2000).

Ballhausen, C. J. Ligand Field Theory (McGraw-Hill, 1962).

Popovic, Z. V. Phonons in CuGeO3 studied using polarized far-infrared and Raman-scattering spectroscopies. Phys. Rev. B 52, 4185–4190 (1995).

Huang, H.-Y. et al. Ab initio calculation of d-d excitations in quasi-one-dimensional Cu d9 correlated materials. Phys. Rev. B 84, 235125 (2011).

van den Brink, J. Orbital excitations in LaMnO3. Phys. Rev. Lett. 87, 217202 (2001).

Yamaguchi, K., Kurihara, T., Minami, Y., Nakajima, M. & Suemoto, T. Terahertz time-domain observation of spin reorientation in orthoferrite ErFeO3 through magnetic free induction decay. Phys. Rev. Lett. 110, 137204 (2013).

Afanasiev, D. et al. Control of the ultrafast photoinduced magnetization across the Morin transition in DyFeO3. Phys. Rev. Lett. 116, 097401 (2016).

Bossini, D. et al. Femtosecond activation of magnetoelectricity. Nat. Phys. 14, 370–374 (2018).

Johnson, S. L. et al. Femtosecond dynamics of the collinear-to-spiral antiferromagnetic phase transition in CuO. Phys. Rev. Lett. 108, 037203 (2012).

Randi, F. Low-Energy Physics in Strongly Correlated Materials via Nonlinear Spectroscopies. PhD thesis, Univ. Trieste (2017).

Giusti, F. Intensity and Fluctuation Dynamics in Pump-Probe Experiments in Complex Materials. PhD thesis, Univ. Trieste (2018).

Trebino, R. et al. Measuring ultrashort laser pulses in the time-frequency domain using frequency-resolved optical gating. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 68, 3277–3295 (1997).

Giannozzi, P. et al. QUANTUM ESPRESSO: a modular and open-source software project for quantum simulations of materials. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 21, 395502 (2009).

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865–3868 (1996).

Setten, M. V. et al. The PSEUDODOJO: training and grading a 85 element optimized norm-conserving pseudopotential table. Comp. Phys. Commun. 226, 39–54 (2018).

Wu, H., Qian, M. C. & Zheng, Q. Q. Insulating band structure of CuGeO3. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 11, 209–219 (1999).

Dudarev, S. L., Botton, G. A., Savrasov, S. Y., Humphreys, C. J. & Sutton, A. P. Electron-energy-loss spectra and the structural stability of nickel oxide: an LSDA+U study. Phys. Rev. B 57, 1505–1509 (1998).

Marques, M. A., Castro, A., Bertsch, G. F. & Rubio, A. octopus: a first-principles tool for excited electron-ion dynamics. Comp. Phys. Commun. 151, 60–78 (2003).

Castro, A. et al. octopus: a tool for the application of time-dependent density functional theory. Phys. Status Solidi B 243, 2465–2488 (2006).

Acknowledgements

We thank A. Revcolevschi for providing the CuGeO3 samples and the critical reading of the manuscript and A. Cavalleri for his feedback on the manuscript and project. This work was mainly supported by the ERC grant INCEPT no. 677488. F. Glerean was supported by the Italian Ministry of Education, University and Research, MIUR (SIR project grant no. RBSI14ZIY2). This work was partially supported by the European Research Council (ERC-2015-AdG694097), the Cluster of Excellence AIM and SFB925. J.v.d.B. aknowledges support from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) through the Würzburg-Dresden Cluster of Excellence ct.qmat (EXC 2147, project ID 390858490) and CRC 1143 (project no. A05, project ID 247310070). F.B. acknowledges that his research has been conducted within the framework of the Trieste Institute for Theoretical Quantum Technologies.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.M. and F. Giusti performed the experiments with support from F. Glerean, G.S. and F.V. A.M. analysed the data. S.M., F.B. and F.V. developed the theoretical model. S.M. performed the analytical calculations with support from F.V. and F.B. S.M., S.L. and A.R. conceived and performed the DFT calculations. T.N. and A.C. performed the finite-difference time-domain calculations. J.v.d.B., D.F. and F.B. conceived the effective Hamiltonian model. A.M., S.M., F.B. and D.F. led the data interpretation and the drafting of the manuscript with contributions from all other authors. D.F. conceived and managed the project.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Peer review information Nature Physics thanks Venkatraman Gopalan and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figs. 1–11, experimental details, complementary results, discussion, details about the theory and calculations, and Tables 1 and 2.

Source data

Source Data Fig. 1

Source data for Fig. 1c.

Source Data Fig. 2

Source data for Fig. 2

Source Data Fig. 3

Source data for Fig. 3.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Marciniak, A., Marcantoni, S., Giusti, F. et al. Vibrational coherent control of localized d–d electronic excitation. Nat. Phys. 17, 368–373 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41567-020-01098-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41567-020-01098-8

This article is cited by

-

Ultrafast pump-probe phase-randomized tomography

Light: Science & Applications (2025)

-

Anomalous non-equilibrium response in black phosphorus to sub-gap mid-infrared excitation

Nature Communications (2022)

-

Probing the interplay between lattice dynamics and short-range magnetic correlations in CuGeO3 with femtosecond RIXS

npj Quantum Materials (2021)