Abstract

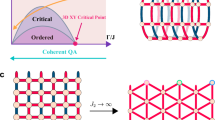

The formation of topological defects after a symmetry-breaking phase transition is an overarching phenomenon that encodes the underlying dynamics. The Kibble–Zurek mechanism (KZM) describes these non-equilibrium dynamics of second-order phase transitions and predicts a power-law relationship between the cooling rates and the density of topological defects. It has been verified as a successful model in a wide variety of physical systems, including structure formation in the early Universe and condensed-matter materials. However, it is uncertain if the KZM mechanism is also valid for topologically trivial Ising domains, one of the most common and fundamental types of domain in condensed-matter systems. Here we show that the cooling rate dependence of Ising domain density follows the KZM power law in two different three-dimensional structural Ising domains: ferro-rotation domains in NiTiO3 and polar domains in BiTeI. However, although the KZM slope of NiTiO3 agrees with the prediction of the 3D Ising model, the KZM slope of BiTeI exceeds the theoretical limit, providing an example of steepening KZM slope with long-range dipolar interactions. Our results demonstrate the validity of KZM for Ising domains and reveal an enhancement of the power-law exponent for transitions of non-topological quantities with long-range interactions.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$32.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $21.58 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

Source data are available with this paper. Other data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Code availability

The codes for the domain analysis of this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Hohenberg, P. C. & Halperin, B. I. Theory of dynamic critical phenomena. Rev. Mod. Phys. 49, 435–479 (1977).

Kibble, T. W. B. Topology of cosmic domains and strings. J. Phys. A: Math. Gen. 9, 1387–1398 (1976).

Zurek, W. H. Cosmological experiments in superfluid helium? Nature 317, 505–508 (1985).

Hendry, P. C., Lawson, N. S., Lee, R. A. M., McClintock, P. V. E. & Williams, C. D. H. Generation of defects in superfluid 4He as an analogue of the formation of cosmic strings. Nature 368, 315–317 (1994).

Maniv, A., Polturak, E. & Koren, G. Observation of magnetic flux generated spontaneously during a rapid quench of superconducting films. Phys. Rev. Lett. 91, 197001 (2003).

Chuang, I., Durrer, R., Turok, N. & Yurke, B. Cosmology in the laboratory: defect dynamics in liquid crystals. Science 251, 1336–1342 (1991).

Pyka, K. et al. Topological defect formation and spontaneous symmetry breaking in ion Coulomb crystals. Nat. Commun. 4, 2291 (2013).

Ulm, S. et al. Observation of the Kibble–Zurek scaling law for defect formation in ion crystals. Nat. Commun. 4, 2290 (2013).

Su, S.-W., Gou, S.-C., Bradley, A., Fialko, O. & Brand, J. Kibble-Zurek scaling and its breakdown for spontaneous generation of Josephson vortices in Bose-Einstein condensates. Phys. Rev. Lett. 110, 215302 (2013).

Lin, S.-Z. et al. Topological defects as relics of emergent continuous symmetry and Higgs condensation of disorder in ferroelectrics. Nat. Phys. 10, 970–977 (2014).

Kolodrubetz, M., Pekker, D., Clark, B. K. & Sengupta, K. Nonequilibrium dynamics of bosonic Mott insulators in an electric field. Phys. Rev. B 85, 100505 (2012).

Chen, D., White, M., Borries, C. & DeMarco, B. Quantum quench of an atomic Mott insulator. Phys. Rev. Lett. 106, 235304 (2011).

Corman, L. et al. Quench-induced supercurrents in an annular Bose gas. Phys. Rev. Lett. 113, 135302 (2014).

Nikoghosyan, G., Nigmatullin, R. & Plenio, M. B. Universality in the dynamics of second-order phase transitions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 116, 080601 (2016).

Hubert, A. & Schäfer, R. in Magnetic Domains 99–335 (Springer, 1998).

Lerch, M., Boysen, H., Neder, R., Frey, F. & Laqua, W. Neutron scattering investigation of the high temperature phase transition in NiTiO3. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 53, 1153–1156 (1992).

Boysen, H. & Altorfer, F. A neutron powder investigation of the high-temperature phase transition in NiTiO3. Z. Kristallogr. Cryst. Mater. 210, 328–337 (1995).

Jin, W. et al. Observation of a ferro-rotational order coupled with second-order nonlinear optical fields. Nat. Phys. 16, 42–46 (2019).

Hayashida, T. et al. Visualization of ferroaxial domains in an order-disorder type ferroaxial crystal. Nat. Commun. 11, 4582 (2020).

Hlinka, J., Privratska, J., Ondrejkovic, P. & Janovec, V. Symmetry guide to ferroaxial transitions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 116, 177602 (2016).

Lawson, C. A., Nord, G. L., Dowty, E. & Hargraves, R. B. Antiphase domains and reverse thermoremanent magnetism in ilmenite-hematite minerals. Science 213, 1372–1374 (1981).

Cheong, S.-W., Lim, S., Du, K. & Huang, F.-T. Permutable SOS (symmetry operational similarity). npj Quantum Mater. 6, 58 (2021).

Danz, R. & Gretscher, P. C-DIC: a new microscopy method for rational study of phase structures in incident light arrangement. Thin Solid Films 462–463, 257–262 (2004).

Bray, A. J. Theory of phase-ordering kinetics. Adv. Phys. 51, 481–587 (2002).

Hasenbusch, M. Restoring isotropy in a three-dimensional lattice model: the Ising universality class. Phys. Rev. B 104, 014426 (2021).

Hasenbusch, M., Pinn, K. & Vinti, S. Critical exponents of the three-dimensional Ising universality class from finite-size scaling with standard and improved actions. Phys. Rev. B 59, 11471–11483 (1999).

Ferrenberg, A. M., Xu, J. & Landau, D. P. Pushing the limits of Monte Carlo simulations for the three-dimensional Ising model. Phys. Rev. E 97, 043301 (2018).

Campostrini, M., Pelissetto, A., Rossi, P. & Vicari, E. 25th-order high-temperature expansion results for three-dimensional Ising-like systems on the simple-cubic lattice. Phys. Rev. E 65, 066127 (2002).

Adzhemyan, L. T. et al. The dynamic critical exponent z for 2d and 3d Ising models from five-loop ε expansion. Phys. Lett. A 425, 127870 (2022).

Schweitzer, D., Schlichting, S. & von Smekal, L. Spectral functions and dynamic critical behavior of relativistic Z2 theories. Nucl. Phys. B 960, 115165 (2020).

Grassberger, P. Damage spreading and critical exponents for ‘model A’ Ising dynamics. Phys. A Stat. Mech. Appl. 214, 547–559 (1995).

Wang, F., Hatano, N. & Suzuki, M. Study on dynamical critical exponents of the Ising model using the damage spreading method. J. Phys. A: Math. Gen. 28, 4543–4552 (1995).

Münkel, C., Heermann, D. W., Adler, J., Gofman, M. & Stauffer, D. The dynamical critical exponent of the two-, three- and five-dimensional kinetic Ising model. Phys. A Stat. Mech. Appl. 193, 540–552 (1993).

Hasenbusch, M. Dynamic critical exponent z of the three-dimensional Ising universality class: Monte Carlo simulations of the improved Blume-Capel model. Phys. Rev. E 101, 022126 (2020).

Matz, R., Hunter, D. L. & Jan, N. The dynamic critical exponent of the three-dimensional Ising model. J. Stat. Phys. 74, 903–908 (1994).

Ishizaka, K. et al. Giant Rashba-type spin splitting in bulk BiTeI. Nat. Mater. 10, 521–526 (2011).

Lee, A. C. et al. Chiral electronic excitations in a quasi-2D Rashba system BiTeI. Phys. Rev. B 105, L161105 (2022).

Tomokiyo, A., Okada, T. & Kawano, S. Phase diagram of system (Bi2Te3)-(BiI3) and crystal structure of BiTeI. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 16, 291–298 (1977).

Butler, C. J. et al. Mapping polarization induced surface band bending on the Rashba semiconductor BiTeI. Nat. Commun. 5, 4066 (2014).

Kim, J., Rabe, K. M. & Vanderbilt, D. Negative piezoelectric response of van der Waals layered bismuth tellurohalides. Phys. Rev. B 100, 104115 (2019).

Sakano, M. et al. Strongly spin-orbit coupled two-dimensional electron gas emerging near the surface of polar semiconductors. Phys. Rev. Lett. 110, 107204 (2013).

Shi, Y. et al. A ferroelectric-like structural transition in a metal. Nat. Mater. 12, 1024–1027 (2013).

Huang, F.-T. et al. Polar and phase domain walls with conducting interfacial states in a Weyl semimetal MoTe2. Nat. Commun. 10, 4211 (2019).

Zhou, W. X. & Ariando, A. Review on ferroelectric/polar metals. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 59, SI0802 (2020).

Dutta, A. & Dutta, A. Probing the role of long-range interactions in the dynamics of a long-range Kitaev chain. Phys. Rev. B 96, 125113 (2017).

Jaschke, D., Maeda, K., Whalen, J. D., Wall, M. L. & Carr, L. D. Critical phenomena and Kibble–Zurek scaling in the long-range quantum Ising chain. New J. Phys. 19, 033032 (2017).

Puebla, R., Marty, O. & Plenio, M. B. Quantum Kibble–Zurek physics in long-range transverse-field Ising models. Phys. Rev. A 100, 032115 (2019).

Acknowledgements

We thank S. Lin and W. H. Zurek for their helpful comments on this work. The work at Rutgers University was supported by the US Department of Energy (DOE) under grant no. DOE:DE-FG02-07ER46382, and the work at Pohang University (C.W.) was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea funded by the Ministry of Science and ICT (grant nos. 2022M3H4A1A04074153 and 2020M3H4A2084417). F.J.G.-R. acknowledges financial support from the European Commission FET-Open project AVaQus GA 899561. The X-ray powder diffraction measurements were supported by the US DOE, Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Science (BES), Materials Sciences and Engineering Division, and the use of the Advanced Photon Source (APS) by the DOE BES Scientific User Facilities Division under contract no. DE-AC02-06CH11357.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.-W.C. initiated and guided the project. C.W. and C.D. grew the crystals. K.D. and X.F. prepared and measured the samples. K.D. performed the data analysis. F.-T.H. conducted the TEM measurements. W.X. and H.Y. conducted the high-temperature X-ray studies. F.J.G.-R. and A.D.C. performed the theoretical analysis. K.D., F.J.G.-R., A.D.C. and S.-W.C. wrote the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Physics thanks Quintin Meier and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Extended Data Fig. 1 Ferro-rotational domains after polishing in NiTiO3.

(a) CDIC image of NiTiO3 surface after polishing. (b) Corresponding atomic force microscopy topography image of the blue dotted region in (a). (c) Corresponding line profile of the red dashed line in (b).

Extended Data Fig. 2 Confirming ferro-rotational domains in NiTiO3 by TEM.

(a) Selected area electron diffraction (SAED) pattern of quenched NiTiO3 single crystal along [\(\bar{1}2\)0]. Side-view dark-field TEM images by selecting spots (b) (214) and (c) (211), showing CCW and CW ferro-rotational domains. The zone [\(\bar{1}\)20] is indexed in respect to CCW ferro-rotational domain and become zone [\(\bar{2}\)10] in respect to CW domain. Note that the Bragg spot (214) is converted into (12\(\bar{4}\)) in the reciprocal space by the twofold rotation as two ferro-rotation domains do in real space. This produces a corresponding contrast difference between the two ferro-rotational domains that allows us to uniquely confirm the existence of ferro-rotational domains.

Extended Data Fig. 3 CDIC images and corresponding black/white images of ferro-rotation domains for KZM plot in NiTiO3 crystals.

Their image sizes and cooling rates are labeled individually. Images of crystals with the same cooling rate are grouped by black squares, and their average domain density is used for the KZM plot in Fig. 2(a). The cooling rate of the quenched crystal was estimated to be 15000°C/h at its ferro-rotational transition temperature. Due to its small domain size, the domain pattern of the quenched sample was imaged by AFM topography instead of the typical CDIC optical microscope method.

Extended Data Fig. 4 High-temperature X-ray powder diffraction of BiTeI.

(a) Lattice constants and the cell volume as a function of temperature upon heating up to 550°C. Dashed black curves are first derivatives of corresponding lattice parameters, which show clear anomalies at 460°C. (b) Selected X-ray diffraction spectra of BiTeI near the transition temperature upon heating, demonstrating continuous and smooth shifts of X-ray peaks. (c) (100) X-ray diffraction peak of BiTeI at selected temperatures upon heating with no signs of phase coexistence near the transition temperature. The continuous evolution of lattice parameters without abrupt jumps and signs of phase coexistence near the transition unambiguously confirms the second-order nature of this phase transition.

Extended Data Fig. 5 PFM/TEM images and corresponding black/white images of polar domains for KZM plot in BiTeI.

Their image sizes and cooling rates are labeled individually. Images with the same scale are grouped by black squares to facilitate an easier comparison.

Extended Data Fig. 6 Ruling out artifacts from the coarsening effect and chemical defects.

One 0.5°C/h-cooled (green data point) and one 20°C/h-cooled (blue data point) BiTeI crystal with an additional coarsening at 400°C for 300 hours are plotted with regularly-collected KZM data. No significant changes in domain density are found after excessive coarsening. An additional post-annealing (40°C/h, pink data point) can convert a previously slowly-cooled (0.5°C/h) crystal to a state with a high domain density, which illustrates polar domains are not pinned by chemical defects.

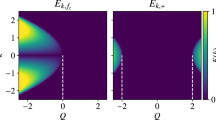

Extended Data Fig. 7 Relaxation time as a function of reduced temperature with possible small dynamical critical exponent z in BiTeI.

For 3D Ising model, the spatial critical exponent v ≈ 0.63. The surprisingly small dynamical critical exponent z from our experiments indicates that the relaxation time (τ) near the polar transition in BiTeI has a much broader and slower response to the reduced temperature Tred =(T-Tc)/Tc, where Tc is the polar transition temperature.

Extended Data Fig. 8 Temperature-dependent resistivity and the expected resistivity of BiTeI at the transition.

The measured resistivity of BiTeI can be well fitted by the exponential grow function with R2 = 0.99989. Based the fitting model, the elevated resistivity of BiTeI near the transition temperature at Tc ≈470°C can potentially reach an order of 0.01 Ω•cm, which may enable non-vanishing effects of long-range dipolar interactions.

Source data

Source Data Fig. 1

Numerical source data.

Source Data Fig. 2

Numerical source data.

Source Data Fig. 3

Numerical source data.

Source Data Fig. 4

Numerical source data.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Du, K., Fang, X., Won, C. et al. Kibble–Zurek mechanism of Ising domains. Nat. Phys. 19, 1495–1501 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41567-023-02112-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41567-023-02112-5

This article is cited by

-

Electric toroidal invariance generates distinct transverse electromagnetic responses

Nature Physics (2025)

-

Three-dimensional imaging of topologically protected strings in a multiferroic nanocrystal

Communications Materials (2025)

-

Dynamic phase transition in 1T-TaS2 via a thermal quench

Nature Physics (2025)

-

Finite-time scaling beyond the Kibble-Zurek prerequisite in Dirac systems

Nature Communications (2025)

-

When Ising met Kibble–Zurek

Nature Physics (2023)