Abstract

Discovered first in synthetic alloys and subsequently in nature, quasicrystals exhibit forbidden symmetries and long-range orientational order but lack translational periodicity. Despite numerous theoretical and numerical studies, the fabrication of quasicrystals remains a challenge, with limited means available for observing their formation in situ. As a result, questions remain regarding the detailed mechanisms of quasicrystal formation and stabilization. Observable under optical microscopes, micrometre-scale colloidal systems have been used for decades as atomic models with considerably slowed-down dynamics and tuneable interactions through surface modification, solution composition and applied external fields. Here we show that two-dimensional dodecagonal quasicrystals can be reversibly assembled from single-component microspheres using a combination of orthogonally applied magnetic and electric fields. Varying the magnitude and frequency of the applied fields not only determines the resulting structures but also sets the phase transition dynamics via an effective system temperature. We hypothesize that these quasicrystals are energetically stabilized with their formation driven by an isotropic double-well pair potential, although the origin of the second minimum remains an open question.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$32.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $21.58 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

Raw datasets generated during this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

The code of the numerical computations (with detailed documentation) is available on GitHub at https://github.com/stochasticHydroTools/RigidMultiblobsWall/tree/master/Lubrication/Lubrication_Examples/Colloidal_QuasiCrystal.

References

Shechtman, D., Blech, I., Gratias, D. & Cahn, J. W. Metallic phase with long-range orientational order and no translational symmetry. Phys. Rev. Lett. 53, 1951–1953 (1984).

Bindi, L., Steinhardt, P. J., Yao, N. & Lu, P. J. Natural quasicrystals. Science 324, 1306–1309 (2009).

Levi, L. et al. Disorder-enhanced transport in photonic quasicrystals. Science 332, 1541–1544 (2011).

Matsui, T., Agrawal, A., Nahata, A. & Vardeny, Z. V. Transmission resonances through aperiodic arrays of subwavelength apertures. Nature 446, 517–521 (2007).

Vardeny, Z. V., Nahata, A. & Agrawal, A. Optics of photonic quasicrystals. Nat. Photonics 7, 177–187 (2013).

Yu, S., Qiu, C.-W., Chong, Y., Torquato, S. & Park, N. Engineered disorder in photonics. Nat. Rev. Mater. 6, 226–243 (2021).

PaBens, M. et al. Interface-driven formation of a two-dimensional dodecagonal fullerene quasicrystal. Nat. Commun. 8, 15367 (2017).

Wasio, N. A. et al. Self-assembly of hydrogen-bonded two-dimensional quasicrystals. Nature 507, 86–89 (2014).

Urgel, J. I. et al. Quasicrystallinity expressed in two-dimensional coordination networks. Nat. Chem. 8, 657–662 (2016).

Talapin, D. V. et al. Quasicrystalline order in self-assembled binary nanoparticle superlattices. Nature 461, 964–967 (2009).

Xiao, C., Fujita, N., Miyasaka, K., Sakamoto, Y. & Terasaki, O. Dodecagonal tiling in mesoporous silica. Nature 487, 349–353 (2012).

Ye, X. et al. Quasicrystalline nanocrystal superlattice with partial matching rules. Nat. Mater. 16, 214–219 (2017).

Nagaoka, Y., Zhu, H., Eggert, D. & Chen, O. Single-component quasicrystalline nanocrystal superlattices through flexible polygon tiling rule. Science 362, 1396–1400 (2018).

Fischer, S. et al. Colloidal quasicrystals with 12-fold and 18-fold diffraction symmetry. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 108, 1810–1814 (2011).

Yue, K. et al. Geometry induced sequence of nanoscale Frank–Kasper and quasicrystal mesophases in giant surfactants. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 113, 14195–14200 (2016).

Liu, L., Li, Z., Li, Y. & Mao, C. Rational design and self-assembly of two-dimensional, dodecagonal DNA quasicrystals. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 4248–4251 (2019).

Zhang, J. & Bates, F. S. Dodecagonal quasicrystalline morphology in a poly(styrene-b-isoprene-b-styrene-b-ethylene oxide) tetrablock terpolymer. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 7636–7639 (2012).

Hayashida, K., Dotera, T., Takano, A. & Matsushita, Y. Polymeric quasicrystal: mesoscopic quasicrystalline tiling in ABC star polymers. Phys. Rev. Lett. 98, 195502 (2007).

Gillard, T. M., Lee, S. & Bates, F. S. Dodecagonal quasicrystalline order in a diblock copolymer melt. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 113, 5167–5172 (2016).

Steurer, W. Quasicrystals: What do we know? What do we want to know? What can we know? Acta Crystallogr. Sect. A 74, 1–11 (2018).

Nagaoka, Y., Schneider, J., Zhu, H. & Chen, O. Quasicrystalline materials from non-atom building blocks. Matter 6, 30–58 (2023).

Du, D., Li, D., Thakur, M. & Biswal, S. L. Generating an in situ tunable interaction potential for probing 2-D colloidal phase behavior. Soft Matter 9, 6867–6875 (2013).

Haji-Akbari, A. et al. Disordered, quasicrystalline and crystalline phases of densely packed tetrahedra. Nature 462, 773–777 (2009).

Dotera, T., Oshiro, T. & Ziherl, P. Mosaic two-lengthscale quasicrystals. Nature 506, 208–211 (2014).

van der Linden, M. N., Doye, J. P. K. & Louis, A. A. Formation of dodecagonal quasicrystals in two-dimensional systems of patchy particles. J. Chem. Phys. 136, 054904 (2012).

Barkan, K., Engel, M. & Lifshitz, R. Controlled self-assembly of periodic and aperiodic cluster crystals. Phys. Rev. Lett. 113, 098304 (2014).

Iacovella, C. R., Keys, A. S. & Glotzer, S. C. Self-assembly of soft-matter quasicrystals and their approximants. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 108, 20935–20940 (2011).

Fayen, E., Filion, L., Foffi, G. & Smallenburg, F. Quasicrystal of binary hard spheres on a plane stabilized by configurational entropy. Phys. Rev. Lett. 132, 048202 (2024).

Scacchi, A., Somerville, W. R. C., Buzza, D. M. A. & Archer, A. J. Quasicrystal formation in binary soft matter mixtures. Phys. Rev. Res. 2, 032043 (2020).

Pattabhiraman, H. & Dijkstra, M. On the formation of stripe, sigma, and honeycomb phases in a core–corona system. Soft Matter 13, 4418–4432 (2017).

Skibinsky, A., Buldyrev, S. V., Scala, A., Havlin, S. & Stanley, H. E. Quasicrystals in a monodisperse system. Phys. Rev. E 60, 2664–2669 (1999).

Zu, M., Tan, P. & Xu, N. Forming quasicrystals by monodisperse soft core particles. Nat. Commun. 8, 2089 (2017).

Schoberth, H. G. et al. Molecular dynamics study of colloidal quasicrystals. Soft Matter 12, 7644–7654 (2016).

Pattabhiraman, H., Gantapara, A. P. & Dijkstra, M. On the stability of a quasicrystal and its crystalline approximant in a system of hard disks with a soft corona. J. Chem. Phys. 143, 164905 (2015).

Lu, P. J. & Weitz, D. A. Colloidal particles: crystals, glasses, and gels. Annu. Rev. Condens. Matter Phys. 4, 217–233 (2013).

Manoharan, V. N. Colloids. Colloidal matter: packing, geometry, and entropy. Science 349, 1253751 (2015).

Li, B., Zhou, D. & Han, Y. Assembly and phase transitions of colloidal crystals. Nat. Rev. Mater. 1, 15011 (2016).

Ceron, S., Gardi, G., Petersen, K. & Sitti, M. Programmable self-organization of heterogeneous microrobot collectives. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 120, e2221913120 (2023).

Hermisson, J., Richard, C. & Baake, M. A guide to the symmetry structure of quasiperiodic tiling classes. J. Phys. I 7, 1003–1018 (1997).

Leung, P. W., Henley, C. L. & Chester, G. V. Dodecagonal order in a two-dimensional lennard-jones system. Phys. Rev. B 39, 446–458 (1989).

Rubinstein, B. & Ben-Abraham, S. I. Vertex frequencies of the hierarchical dodecagonal tiling. Ferroelectrics 250, 417–419 (2001).

Lieu, U. T. & Yoshinaga, N. Formation and fluctuation of two-dimensional dodecagonal quasicrystals. Soft Matter 18, 7497–7509 (2022).

Shirzad, K. & Viney, C. A critical review on applications of the avrami equation beyond materials science. J. R. Soc. Interface 20, 20230242 (2023).

Hensley, A., Videbæk, T. E., Seyforth, H., Jacobs, W. M. & Rogers, W. B. Macroscopic photonic single crystals via seeded growth of DNA-coated colloids. Nat. Commun. 14, 4237 (2023).

Dotera, T. Toward the discovery of new soft quasicrystals: from a numerical study viewpoint. J. Polym. Sci. Part B 50, 155–167 (2012).

Ristenpart, W. D., Aksay, I. A. & Saville, D. A. Electrohydrodynamic flow around a colloidal particle near an electrode with an oscillating potential. J. Fluid Mech. 575, 83–109 (2007).

Fernández-Mateo, R., García-Sánchez, P., Calero, V., Morgan, H. & Ramos, A. Stationary electro-osmotic flow driven by AC fields around charged dielectric spheres. J. Fluid Mech. 924, R2 (2021).

Grob, D. T., Wise, N., Oduwole, O. & Sheard, S. Magnetic susceptibility characterization of superparamagnetic microspheres. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 452, 134–140 (2018).

Zimmermann, C., Herson, P., Neeves, K. & Marr, D. Multimodal microwheel swarms for targeting in three-dimensional networks. Sci. Rep. 12, 5078 (2022).

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge discussions with D. T. Wu on QCs and J. R. Maestas on phason strain calculations. Y.G., D.W.M.M. and N.W. acknowledge support from the National Science Foundation (CBET-1762616) and the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NNX13AQ54G). N.W. also acknowledges support from the National Science Foundation (CBET-2030480).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

N.W. and D.W.M.M. conceived and designed the work. Y.G. performed the experiments. B.S. performed the simulation work. All authors contributed to the data analysis and the writing of the paper.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Physics thanks Martin Dulle and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Extended Data Fig. 1 Experimental setup and magnetic field configuration.

a, The application of orthogonal magnetic and electric fields. b, In-situ measurement of the diffraction pattern. c, The planar oscillating magnetic field (\({\boldsymbol{B}}={B}_{0}\cos \left(2\pi {f}_{B}t\right)\hat{{\bf{x}}}+{B}_{0}\sin \left(4\pi {f}_{B}t\right)\hat{{\bf{y}}}\)) can generate time-averaged attractive magnetic interactions between particles while minimizing net particle rotation. The colored arrows indicate the instantaneous field orientation and magnitude over one period, T = 1/fB.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Ideal QC constructed using the extended Schlottmann inflation rule.

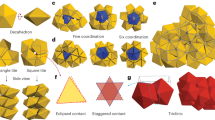

a, The real-space structure and local particle environments. The Z, σ, and H environments are labeled in green, red, and yellow, respectively. The particles at the boundaries are labeled in yellow. b, The corresponding diffraction pattern.

Extended Data Fig. 3 Large field of view of Fig. 1c.

Extended Data Fig. 4 Heterogeneous HX-to-QC transition initiated from a domain boundary.

The real-space optical image is overlayed with the particle environment identification following the same color codes specified in Fig. 1d (E0 = 1.14 × 105 V/m, B0 = 0.92 mT, and fB = 80 Hz). The phase transition is triggered by increasing fE from 1k to 20k Hz.

Extended Data Fig. 5 The local bond orientation order of a poly-quasicrystalline structure shown in Fig. 4d.

a, Magnitude. b, Phase.

Extended Data Fig. 6 The assembly of 2.8 µm particles (M-270 carboxylic acid) under electric and magnetic fields.

a, Closed-packed ladder formed under a magnetic field only (B0 = 1.32 mT, and fB = 80 Hz) is transformed into a mixture of equilateral triangles and squares under combined electric and magnetic fields (E0 = 1.2 × 105 V/m, fE = 2k Hz, B0 = 1.32 mT, and fB = 80 Hz). b, QC formation at higher particle concentration (E0 = 1.14 × 105 V/m, B0 = 1.32 mT, and fB = 80 Hz). The real space image is overlayed with the local particle environments. c, Calculated diffraction pattern. d, Phase diagram (B0 = 1.53 mT, fB = 80 Hz). 0.033 wt% F127 is added to the suspension.

Extended Data Fig. 7 Permanent dipole moment measurement.

a, The angular frequency of a spinning bead under a circularly rotating magnetic field at different field strengths and frequencies. Error bars are standard deviation (SD) for n = 10 independent measurements. Data are presented as mean values +/− SD. b, The dependence of cutoff frequency on field strength. Error bars are standard deviation for n = 10 independent measurements. Data are presented as mean values +/− SD. c, The orientation of a polystyrene nanoparticle (NP) labeled bead under an applied DC magnetic field (B = 0.5 mT). The black arrow indicates the direction of the magnetic field. The white arrow represents the particle orientation defined by the vector connecting the particle center to the NP centroid. d-e, When the applied field is suddenly rotated 150° counterclockwise, the particle also rotates 150° as indicated by its orientation vector.

Extended Data Fig. 8 The susceptibility χ and electric polarization coefficient K of M-450 epoxy particles.

a, The separation between particle pairs under a one-dimensional DC magnetic field (B0 = 1.0 mT). Each color represents results obtained from a single pair of particles. b, The separation between particle pairs under a vertical AC electric field (E0 = 105 V/m and fE = 9 kHz). Dashed lines represent the lower and upper bounds of the fit.

Extended Data Fig. 9 Non close-packed hexagonal arrays formed under an AC electric field only.

a-e, The frequency changes from 0.6k to 20k Hz while E0 is kept constant (105 V/m). The scale bar (20 µm) is the same for all figures. f, The separation between neighboring particles at different frequencies. Error bars represent mean ± SD (n = 200 independent measurements).

Extended Data Fig. 10 Assembly of M-270 carboxylic acid particles in DMSO.

a, Close-packed clusters under an in-plane oscillating magnetic field. B0 = 2.1 mT and fB = 80 Hz. b, The same clusters upon the superposition of an out-of-plane electric field (E0 = 1.2 × 105 V/m, fE = 600 Hz).

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Sections 1–5, Table 1 and video descriptions.

Supplementary Video 1

The transformation of small colloidal clusters under orthogonal electric and magnetic fields. Under a planar rotating magnetic field (B0 = 0.92 mT, fB,x = fB,y = 80 Hz), four (ten) particles form a diamond-like (ladder-like) cluster. After this, the magnetic field is switched to an oscillating magnetic field, where \({f}_{B,y}=2{f}_{B,x}\) = 160 Hz, stopping rotation. After superimposing a vertical electric field (E0 = 1.3 × 105 V m−1, fE = 1,000 Hz), the cluster transforms into a square (mixed triangle–square).

Supplementary Video 2

HX-to-QC phase transition: heterogeneous nucleation from one side of the domain boundary. The real-space images, particle environment, calculated diffraction patterns, \({\psi }_{12}\) and \({\theta }_{12}\) are shown. Electric field frequency fE is increased from 1,000 to 20,000 Hz while other field conditions are kept constant (B0 = 0.92 mT, \({f}_{B,y}=2{f}_{B,x}\) = 160 Hz, E0 = 1.14 × 105 V m−1). The grain boundary (not shown) is located at right. In real-space images of the QC phase, not all bright circles correspond to the centre of the particles. Those located at the centre of squares are voids. All videos are sped up 5×.

Supplementary Video 3

θ12 histogram during the HX-to-QC transition.

Supplementary Video 4

HX-to-QC phase transition: heterogeneous nucleation from both sides of the domain boundary. The real-space images, particle environment, calculated diffraction patterns, ψ12 and θ12 are shown. The electric field frequency fE is increased from 1,000 to 20,000 Hz while other field conditions are kept constant (B0 = 0.92 mT, \({f}_{B,y}=2{f}_{B,x}\) = 160 Hz, E0 = 1.14 × 105 V m−1). All videos are sped up 1.5×.

Supplementary Audio 5

HX-to-QC phase transition: homogeneous nucleation from the bulk of a hexagonal crystal. The real-space images, particle environment, calculated diffraction patterns, ψ12 and θ12 are shown. The electric field frequency fE is increased from 1,000 to 20,000 Hz while other field conditions are kept constant (B0 = 0.92 mT, \({f}_{B,y}=2{f}_{B,x}\) = 160 Hz, E0 = 1.2 × 105 V m−1). All videos are sped up 3×.

Supplementary Video 6

HX-to-QC phase transition: homogeneous nucleation from the bulk of a hexagonal crystal. Part I: the HX transforms into QC when the electric field frequency fE is increased from 1,000 to 20,000 Hz directly while other field conditions (B0 = 0.92 mT, \({f}_{B,y}=2{f}_{B,x}\) = 160 Hz, E0 = 1.2 × 105 V m−1) are held constant. Part II: the HX transforms into QC when the electric field frequency fE is increased from 1,000 to 10,000 Hz and then to 20,000 Hz via a two-step change. Other field conditions (B0 = 0.92 mT, \({f}_{B,y}=2{f}_{B,x}\) = 160 Hz, E0 = 1.2 × 105 V m−1) are held constant. Both videos are sped up 3×.

Supplementary Video 7

SQ-to-σ and SQ-to-H phase transitions. Part I: phase transition from a square lattice to a σ phase. The magnetic field is increased from B0 = 0.92 to 1.00 mT. \({f}_{B,y}=2{f}_{B,x}\) = 160 Hz, E0 = 1.2 × 105 V m−1, fE = 3,000 Hz. Part II: phase transition from a square lattice to an H phase. Bx is increased from 0.92 to 1.07 mT while other field conditions are kept constant. \({f}_{B,y}=2{f}_{B,x}\) = 160 Hz, By = 0.92 mT, E0 = 1.2 × 105 V m−1, fE = 3,000 Hz.

Supplementary Video 8

Liquid-to-QC phase transition. Particles are suspended in a thin liquid film confined between two ITO glasses separated by 50 μm. The surface density is ~60%. When the applied electric field and magnetic field (E0 = 1.15 × 105 V m−1, fE = 3,000 Hz, B0 = 0.92 mT, \({f}_{B,y}=2{f}_{B,x}\) = 160 Hz) are applied simultaneously, particles aggregate and form QCs. Both videos are sped up 3×.

Supplementary Video 9

Reorientation of an isolated particle under a d.c. magnetic field. The microparticle is first coated with a 500-nm fluorescent polystyrene nanoparticle to identify the orientation (B0 = 0.5 mT). The video is sped up 3×.

Supplementary Video 10

Experiment and numerical simulation of particles with permanent magnetic dipoles under orthogonally applied magnetic and electric fields. Part I: a ladder-like hexamer is transformed into triangle–square packing and then a ring as the electric field increases. Left: experiment. Right: simulation. The arrows show the orientation of the permanent dipoles. Part II: transformation from hexagonal colloidal clusters to σ and H motifs upon the application of electric field. Left: experiment. Right: simulation. Other field conditions are constant (B0 = 0.92 mT, fB = 80 Hz, fE = 9,000 Hz). The video is sped up 3×.

Source data

Source Data Fig. 1

Source data for Fig. 1.

Source Data Fig. 2

Source data for Fig. 2.

Source Data Fig. 3

Source data for Fig. 3.

Source Data Fig. 4

Source data for Fig. 4.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 2

Source data for Extended Data Fig. 2.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 3

Source data for Extended Data Fig. 3.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 4

Source data for Extended Data Fig. 4.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 5

Source data for Extended Data Fig. 5.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 6

Source data for Extended Data Fig. 6.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 7

Source data for Extended Data Fig. 7.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 8

Source data for Extended Data Fig. 8.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 9

Source data for Extended Data Fig. 9.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Gao, Y., Sprinkle, B., Marr, D.W.M. et al. Direct observation of colloidal quasicrystallization. Nat. Phys. 21, 966–973 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41567-025-02859-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41567-025-02859-z

This article is cited by

-

Triple jump forward

Nature Physics (2025)

-

Watch them grow

Nature Physics (2025)