Abstract

A major challenge in fault-tolerant quantum computation is to reduce both the space overhead, that is, the large number of physical qubits per logical qubit, and the time overhead, that is, the long physical gate sequences needed to implement a logical gate. Here we prove that a protocol using non-vanishing-rate quantum low-density parity-check (QLDPC) codes, combined with concatenated Steane codes, achieves constant space overhead and polylogarithmic time overhead, even when accounting for the required classical processing. This protocol offers an improvement over existing constant-space-overhead protocols. To prove our result, we develop a technique that we call partial circuit reduction, which enables error analysis for the entire fault-tolerant circuit by examining smaller parts composed of a few gadgets. With this approach, we resolve a logical gap in the existing arguments for the threshold theorem for the constant-space-overhead protocol with QLDPC codes and complete its proof. Our work establishes that the QLDPC-code-based approach can realize fault-tolerant quantum computation with a negligibly small slowdown and a bounded overhead of physical qubits.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Quantum computation has promising potential for accelerating the solving of certain classes of computational problems compared with classical computation1,2. However, the inherent fragility of quantum systems poses a major challenge in implementing quantum computations on quantum devices. Fault-tolerant quantum computation (FTQC)3,4 uses quantum error-correcting codes to encode logical qubits and suppress errors, typically incurring a space overhead (the number of physical qubits per logical qubit) and a time overhead (the ratio of physical to logical circuit depth). Currently, two prominent schemes have been proposed for FTQC: one is a concatenated code scheme3,4,5,6, and the other is a quantum low-density parity-check (QLDPC) code scheme7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17. For both schemes, threshold theorems4,5,7,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25 guarantee that the failure probability of the fault-tolerant simulation can be arbitrarily suppressed, provided that the physical error rate is below a certain threshold. Conventional FTQC schemes, using vanishing-rate codes such as those using surface codes9,10 or concatenated Steane codes5, incur polylogarithmic overheads in both space and time with respect to the size of the original quantum circuit.

In recent years, there have been notable advances towards achieving a constant space overhead by using non-vanishing-rate codes. Ref. 11 clarified the properties that non-vanishing-rate QLDPC codes must retain to achieve FTQC with constant space overhead, in combination with concatenated Steane codes. Subsequently, refs. 26,27 showed that quantum expander codes16,26,28 can serve as suitable QLDPC codes for this protocol. In this protocol, logical gates are implemented via gate teleportation using auxiliary states encoded in QLDPC codes3,29,30. The fault-tolerant preparation of these auxiliary states has been challenging without relying on the conventional protocol using concatenated Steane codes3,5. However, the conventional protocol incurs a growing space overhead3,5, which undermines complete gate parallelism when we need to maintain a constant space overhead. As a result, the existing analyses in refs. 11,26,27 require sequential gate implementation, leading to a polynomial increase in the time overhead of this protocol. More recently, ref. 6 resolved this bottleneck by developing a new constant-space-overhead protocol with complete gate parallelism based on concatenated quantum Hamming codes. However, even with this fully parallel execution of gates, the protocol only achieves quasi-polylogarithmic time overhead. Thus, it remains an open question whether it is possible to design an even faster constant-space-overhead protocol that achieves the polylogarithmic time overhead.

From a more fundamental perspective, this question involves a trade-off relation between space and time overhead in FTQC, originally raised in ref. 11 and partially addressed in ref. 6. On the one hand, conventional protocols that use vanishing-rate codes3,4,5,14, whether they are QLDPC codes or concatenated codes, incur polylogarithmic overheads in both space and time. On the other hand, the newer protocols using non-vanishing-rate codes achieve constant space overhead, but this improvement comes at the expense of increased time overhead. Remarkably, both QLDPC-code-based and concatenated-code-based approaches exhibit a similar pattern here as well, where reductions in space overhead have so far led to increases in time overheads beyond the conventional polylogarithmic scaling6,27. The essential focus here is not to propose a marginally improved protocol that outperforms existing ones in certain respects, but rather to address a more fundamental question: whether it is possible to overcome the barrier of super-polylogarithmic time overhead while maintaining constant space overhead.

Another fundamental issue is that the existing analyses of threshold theorems for protocols with QLDPC codes11,26,27,31 assume that classical computations are performed instantaneously on arbitrarily large scales, and before our work, the non-zero runtime of classical computations in implementing FTQC was explicitly taken into account only in the analysis of the threshold theorem for concatenated codes6. To fully analyse the overhead achievable in FTQC, it is essential to incorporate the waiting time for noninstantaneous classical computations into the analysis. Analysing overhead in FTQC must consider all possible bottlenecks, including the runtime of classical computation in executing FTQC (for example, decoding algorithms for error correction and gate teleportation), because the decoding runtime, which has often been considered negligible in theoretical analyses, can dominate the asymptotic scaling32. In fact, accounting for decoding delays in surface-code-based protocols not only increases the exponent in the polylogarithmic time overhead, but may potentially make FTQC infeasible due to severe slowdowns—an issue known as the backlog problem32. Such asymptotically non-negligible classical computations can also render the existence of a threshold non-trivial. In practice, even at current scales, classical computations have already become non-negligible bottlenecks, further underscoring the practical necessity of such comprehensive analyses33,34.

In this Article, we address these challenges and rigorously prove that a polylogarithmic time overhead can be achieved while maintaining a constant space overhead, even when fully accounting for non-zero classical computation times, using the non-vanishing-rate QLDPC codes. Our main theorem is informally stated as follows.

Theorem 1

Let \(\{{C}_{n}^{{\rm{org}}}\}\) be a sequence of original circuits indexed by an integer n. Each circuit \({C}_{n}^{{\rm{org}}}\) has width W(n) and depth D(n), where the size of \({C}_{n}^{{\rm{org}}}\) is polynomially bounded, that is, \(| {C}_{n}^{{\rm{org}}}| =\)\(O(W(n)D(n))=O({\rm{poly}}(n))\) as n → ∞. Then, for all target error ε > 0, there exists a threshold pth > 0 such that, if the physical error rate p is below the threshold, that is, p < pth, then there exists a sequence of fault-tolerant circuits \(\{{C}_{n}^{{\rm{FT}}}\}\) such that the classical output of \({C}_{n}^{{\rm{FT}}}\) is sampled from a probability distribution close to that of \({C}_{n}^{{\rm{org}}}\) in terms of total variation distance at most ε, and \({C}_{n}^{{\rm{FT}}}\) has a width WFT(n) and a depth DFT(n) satisfying

as n → ∞.

The formal statement and proof of this theorem, along with the necessary definitions, are provided in Supplementary Sections II and V, in particular in theorem 11 therein. Our analysis is based on standard assumptions in the previous studies on FTQC5,6,7,11,26 (Supplementary Section II). In particular, we assume no geometric locality constraint on two-qubit gates; a CNOT gate can be applied to an arbitrary pair of physical qubits in a single time step. This is motivated by platforms such as neutral atoms, trapped ions and optics, which may offer pathways to realizing such non-local interactions35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44. To prove theorem 1, we present and analyse a hybrid fault-tolerant protocol that combines concatenated Steane codes5 and non-vanishing-rate QLDPC codes with an efficient decoding algorithm, specifically quantum expander codes16, refining the previous analyses in refs. 11,26,27. Our analysis enables the polylogarithmic time overhead by increasing gate parallelism in the gate operations using gate teleportation, substantially improving the polynomial time overhead of the previous analyses in refs. 11,26,27, while still maintaining a constant space overhead.

Our analysis addresses and fixes a previously overlooked problem in the existing analyses11,26,27 of the threshold theorem for the QLDPC codes. In the analyses of FTQC, it is conventional to consider the local stochastic Pauli error model, where the correlated errors may occur across the entire fault-tolerant quantum circuit, as in refs. 11,26,27. For each code block of the QLDPC codes, the existing analyses in refs. 11,26,27 argue that the physical error rate of the codeword is suppressed after noisy syndrome measurements followed by quantum error correction using decoding algorithms, but this codeword state is on specific code blocks, that is, only in a small part of the entire fault-tolerant circuit on which the local stochastic Pauli error model is defined. This argument overlooks the correlations between this part of the circuit and the rest of the circuit surrounding this part, leaving the overall proof of the threshold theorem incomplete. To address this issue, we introduce a new method called partial circuit reduction. This method enables error analysis of the entire fault-tolerant circuit through the examination of individual gadgets on the code blocks of QLDPC codes. Our approach allows us to leverage the existing results from the decoding algorithms11,26,27 as a black box, so that we fully complete the proof of the threshold theorem for the constant-space-overhead protocol with the QLDPC codes. Furthermore, by combining this method with theoretical advances of the decoding algorithms in refs. 26,27, we show that it is indeed possible to achieve higher parallelization of the logical gates compared with the existing analyses in refs. 11,26,27, resulting in a polylogarithmic time overhead. These advances contribute to a fundamental understanding of the overhead and its space-time trade-off in FTQC and provide a robust foundation for realizing quantum computation.

We note that, in a concurrent work, another fault-tolerant protocol with constant space overhead and polylogarithmic time overhead45 has been proposed, relying on an approach substantially different from ours. The primary contribution of our work lies in the proof of the threshold theorem, which takes into account the non-zero runtime of classical computation.

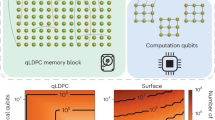

Hybrid approach with QLDPC codes and concatenated codes

In our protocol, quantum expander codes, which are Calderbank–Shor–Steane low-density parity-check codes with a non-vanishing rate, serve as the registers that store and protect logical qubits46,47. Using the conventional notation [[N, K, D]] for the code parameters (N is the number of physical qubits, K is the number of logical qubits and D is the code distance), quantum expander codes16 exhibit parameters of \([[N,K={{\varTheta}}(N),D={{\varTheta}}(\sqrt{N})]]\), so the rate K/N remains positive as N → ∞. Together with the small-set-flip decoder, these codes suppress the probability of decoding failure, which may lead to logical error, exponentially in the code distance, as established in refs. 26,27. These properties make quantum expander codes well suited for high-capacity, robust quantum memory.

To realize a universal gate set that manipulates this QLDPC-encoded quantum memory, we use a hybrid approach involving concatenated Steane codes5,47,48 to prepare auxiliary states encoded by quantum expander codes in a fault-tolerant manner, enabling the logical gates via gate teleportation. The fault-tolerant protocol with concatenated Steane codes can be used to simulate arbitrary original quantum circuits, albeit with polylogarithmic overheads in both time and space5. In our hybrid approach, this concatenated Steane code protocol is crucially used to prepare logical auxiliary states that are encoded in the QLDPC code.

The fault-tolerant preparation of an auxiliary state, denoted by \(\left\vert \psi \right\rangle\), which is a physical state representing a codeword of a QLDPC code that encodes a target logical auxiliary state, can be understood intuitively as follows. While \(\left\vert \psi \right\rangle\) can be prepared by some non-fault-tolerant unitary circuit, such a circuit cannot be directly used for its fault-tolerant preparation. Instead, the idea is to first prepare \(\left\vert \psi \right\rangle\) as a logical state encoded in the concatenated Steane code. Because the well-established fault-tolerant protocol with the concatenated Steane code supports simulation of universal quantum computation, this Steane-encoded version of \(\left\vert \psi \right\rangle\) can be prepared with a sufficiently low logical error rate. We then convert this logical state into the physical state \(\left\vert \psi \right\rangle\) over the physical qubits, by decoding the concatenated Steane code. Roughly speaking, this step introduces errors on each physical qubit at the physical error rate, up to constant factors. This fact was implicitly used in the previous analysis of the constant-space-overhead protocol based on QLDPC codes11, and we provide a rigorous proof and explicit bound on this error rate in Supplementary Appendix A. Although each physical qubit may now suffer errors at the physical error rate, it is important to recall that \(\left\vert \psi \right\rangle\) is already encoded as a codeword of the QLDPC code. Therefore, we can transition to using the decoder of the QLDPC code to continue suppressing its decoding failure probability and protect the encoded logical state in \(\left\vert \psi \right\rangle\). Once these QLDPC-encoded auxiliary states are fault-tolerantly prepared, they enable the implementation of logical Clifford and non-Clifford gates on the QLDPC logical qubits via fault-tolerant gate teleportation3,29,30, thereby equipping our protocol with a universal set of logical operations.

Compilation procedure

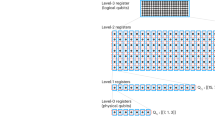

The compilation process in our hybrid fault-tolerant protocol consists of two stages (see Fig. 1 and Supplementary Section III for details).

The process involves two main stages. The aim of the first stage is to convert an original quantum circuit \({C}_{n}^{{\rm{org}}}\) to an intermediate circuit acting on registers, where each register is a collection of at most K qubits. The intermediate circuit is composed of a predetermined set of elementary operations, which includes a \({\left\vert 0\right\rangle }^{\otimes K}\)-state preparation, Clifford-state preparations, magic-state preparations, Pauli-gate operations, a CNOT-gate operation, a ZK-measurement operation, a Bell-measurement operation and a wait operation. The compilation begins with partitioning the qubits of the original circuit into registers. Then, \(\left\vert 0\right\rangle\)-state preparations in the original circuit are replaced by \({\left\vert 0\right\rangle }^{\otimes K}\)-state preparations, and Z-basis measurements are replaced by ZK-measurement operations. Clifford gates (for example, a tensor product of the Hadamard H gate) and non-Clifford gates (for example, a tensor product of T gates) in the original circuit are converted into a Clifford unitary UC acting on two registers and a non-Clifford unitary UT on a single register, respectively. To maintain constant space overhead, the number of the \({\left\vert 0\right\rangle }^{\otimes K}\)-state preparations, the UC gates, the UT gates and the ZK-measurement operations performed at a single time step is limited to \({\varTheta}(W(n)/{\rm{polylog}}(n/{\varepsilon}))\), where W(n) is the original circuit width. Following this, each of the UC gates and the UT gates is replaced by a sequence of elementary operations performing the corresponding teleportation with the aid of auxiliary registers, which is denoted as a UC-gate or a UT-gate abbreviation. The next stage is the compilation of this intermediate circuit into the fault-tolerant circuit \({C}_{n}^{{\rm{FT}}}\). This stage is achieved by replacing each elementary operation with a corresponding gadget, and an EC gadget is inserted between each pair of adjacent gadgets.

First, an original quantum circuit is compiled into an intermediate circuit described as follows. An original circuit consists of initial state preparation, Clifford gates, non-Clifford gates and measurements. The qubits of the original circuit are partitioned into collections of at most K qubits each, called registers6. Here, K is chosen to match the number of logical qubits of the QLDPC code to be used, because each qubit in the intermediate circuit will eventually be regarded as a logical qubit of the code. For the compilation, we rewrite the original circuit using the following operations acting on registers: a \({\left\vert 0\right\rangle }^{\otimes K}\) -state preparation, Clifford unitaries UC acting on two registers, non-Clifford unitaries UT on a single register and a ZK measurement (Fig. 1). To achieve constant overhead, we restrict the number of the preparations, the measurements and the unitary gates executed in parallel, which is done by inserting the wait operations to delay part of the operations. Then, we regard each of the unitary gates as an abbreviation of a gate-teleportation circuit composed of elementary operations and equipped with ancillary registers. Here, the set of the elementary operations is composed of a \({\left\vert 0\right\rangle }^{\otimes K}\)-state preparation, Clifford-state preparations, magic-state preparations, Pauli-gate operations, a CNOT-gate operation, a ZK-measurement operation, a Bell-measurement operation and a wait operation. At this point, the original circuit has been converted to a circuit composed of the elementary operations, which we call the intermediate circuit (Fig. 1).

Next, this intermediate circuit is compiled into a fault-tolerant circuit. In this stage, each elementary operation within the intermediate circuit is replaced with its corresponding gadget, and each register is replaced with the QLDPC code block. Each gadget is a physical circuit designed to perform the logical operation acting on the logical qubits within a code block of the QLDPC code in a fault-tolerant way. As described above, the state-preparation gadget is fault-tolerantly constructed using the concatenated Steane code, while the other gadgets can be implemented transversally for quantum expander codes. Furthermore, an error-correction (EC) gadget acting on each code block is inserted between each pair of adjacent gadgets. Through this process, the final fault-tolerant circuit is constructed.

High parallelism to achieve polylogarithmic time overhead

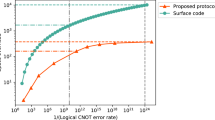

A crucial feature of our protocol is its ability to achieve higher parallelism in executing logical gates compared with existing constant-space-overhead fault-tolerant protocols with QLDPC codes11,26,27, making it possible to achieve polylogarithmic time and constant space overhead simultaneously. In previous analyses11,26,27 for constant-overhead FTQC with QLDPC codes, logical gates could act simultaneously act on only O(W(n)/poly(n/ε)) logical qubits. This limitation naturally led to a polynomial time overhead.

Our protocol overcomes this bottleneck by providing a refined analysis of the required code size for quantum expander codes. These codes exhibit an exponential suppression of decoding failure probability as we increase the code distance. Indeed, this error suppression enables the use of a very small QLDPC code block size, scaling only polylogarithmically. The use of such small code blocks is important for our protocol; it reduces the resources required for the auxiliary states needed for gate teleportation. The QLDPC-encoded auxiliary states required for gate teleportation are prepared using a concatenated Steane code protocol. The fault-tolerant preparation using the concatenated Steane code itself incurs polylogarithmic space and time overheads. Implementation of each logical qubit of the QLDPC code thus requires a polylogarithmic number of physical qubits. Furthermore, each logical gate, implemented via these auxiliary logical states prepared using concatenated Steane codes, also introduces a polylogarithmic time overhead. This polylogarithmic requirement for the QLDPC code block size, in turn, enables the performance of more logical operations, that is, those on \(O(W(n)/{\rm{polylog}}(n/\varepsilon ))\) logical qubits, in parallel at each time step while maintaining the constant space overhead. This substantially increased parallelism in logical gate execution contributes to achieving a polylogarithmic time overhead. The detailed overhead analysis is presented in Supplementary Section V.

New techniques to complete the threshold theorem for FTQC with QLDPC codes

A key challenge in proving the threshold theorem for FTQC with QLDPC codes lies in consistently analysing errors across the entire fault-tolerant circuit, especially when individual code blocks are decoded locally. Existing analyses often focus on error suppression within a single QLDPC code block, overlooking correlations between the block and the rest of the circuit11,26,27, which is globally subject to a local stochastic Pauli error model11,26,27.

To address this fundamental issue, we introduce and utilize a technique called partial circuit reduction. The core motivation for this technique is to provide a systematic framework for analysing errors in a modular fashion. In our fault-tolerant circuit, each operation gadget is followed by EC gadgets for the associated code blocks, forming a circuit segment, which we call a rectangle. Instead of tackling the entire fault-tolerant circuit at once, we sequentially analyse errors in each rectangle. Partial circuit reduction allows us to formally replace a noisy rectangle in the fault-tolerant circuit with its ideally behaving, noiseless version, while appropriately updating the probability distribution of faulty locations in the subsequent, not-yet-analysed parts of the circuit. This step-by-step reduction is easy to use because it only requires analysis of a local segment at a time, while ensuring that the global statistics of fault occurrences continue to follow the same model with updated parameters. This method enables us to systematically manage error correlations and integrate established results from decoding algorithms26,27 as black-box components within a complete and rigorous proof of threshold existence. The detailed mathematical formulation of partial circuit reduction and its application in proving the threshold theorem are presented in Supplementary Section V.

Existence of threshold considering classical computation with non-negligible runtime

With all techniques described above, we prove the threshold theorem for our protocol. A fundamental challenge in theoretical FTQC analysis, often leading to oversimplification, is the reliance on the assumption that classical computation required in error correction and gate teleportation can be performed instantaneously, that is, in zero time26,27,49. In reality, these computations have a non-zero runtime that may grow as the size of original circuits becomes larger. The impact of this additional runtime is not limited to the time overhead. Because errors accumulate during the wait time for classical computation, they can potentially affect space overheads and even the existence of a fault-tolerant threshold.

Our analysis explicitly incorporates this non-zero runtime by inserting appropriate wait periods in the fault-tolerant circuit such that outcomes of classical computation can be used to choose on-demand operations. To establish a threshold under this realistic condition, we identify crucial properties for the decoding algorithm of the QLDPC codes to satisfy. These include: (1) the single-shot property, enabling error correction from a single round of potentially noisy syndrome measurements; (2) iterative execution, where each internal loop of the decoder completes in O(1) time with O(N) classical parallel processors; (3) exponential suppression of decoding failure probability with code distance; and (4) monotonic reduction of residual physical error rate with the number T of the internal loops when physical and syndrome error rates are below certain thresholds. We confirm that the small-set-flip decoder for the quantum expander code26,27 fulfils these requirements. These conditions ensure that the execution of the decoder within the EC gadget (that is, the wait time) can always be kept to a constant time, even if we carefully account for classical processing time. This has enabled us to rigorously prove the existence of a fault-tolerance threshold for our protocol without compromising overhead scalings. The detailed conditions for the decoder and the proof of the threshold theorem are provided in Supplementary Sections IV and V, respectively.

Conclusion and outlook

In this Article, we have presented a hybrid fault-tolerant protocol that combines concatenated codes for gate operations and non-vanishing-rate QLDPC codes (in particular, the quantum expander codes16,26,28) for quantum memory. These results contribute to a fundamental understanding of the overhead and its space-time trade-off required to realize FTQC. Unlike previous analyses that assumed instantaneous classical computations, our work explicitly accounts for non-zero-time classical computation times and their associated error accumulation. Incorporating classical runtime into the overhead analysis and establishing a threshold theorem under this setting not only offers a comprehensive understanding of overheads accounting for every possible bottleneck, but also provides a solid foundation for realizing FTQC. An encouraging aspect of our results is that polylogarithmic time overhead and constant space overhead can be achieved using well-established components: quantum expander codes and concatenated Steane codes. Both of these have been the focus of active experimental research in various physical architectures. Recent theoretical proposals indicate the feasibility of quantum expander codes in scalable systems such as neutral atoms and superconducting circuits42,43,44, while small-scale protocols with the Steane code have already begun to be demonstrated experimentally37,50,51. Our findings indicate a promising potential for low-overhead FTQC using the hybrid approach that combines non-vanishing-rate QLDPC codes and concatenated codes, in addition to relying solely on the code-concatenation approach as proposed in refs. 6,52. With regard to practical implementation, our results clarify the competing time overheads of these two constant-space-overhead approaches, highlighting the importance of a comprehensive investigation into the physical realizability of both approaches.

Data availability

This work does not have any associated data.

References

Montanaro, A. Quantum algorithms: an overview. NPJ Quantum Inf. 2, 15023 (2016).

Dalzell, A. M. et al. Quantum Algorithms: A Survey of Applications and End-to-End Complexities (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2025).

Gottesman, D. An introduction to quantum error correction and fault-tolerant quantum computation. In Proc. Symposia in Applied Mathematics (ed. Lomonaco, S. J. Jr) 13–58 (American Mathematical Society, 2010).

Nielsen, M. A. & Chuang, I. L. Quantum Computation and Quantum Information: 10th Anniversary Edition (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2010).

Aliferis, P., Gottesman, D. & Preskill, J. Quantum accuracy threshold for concatenated distance-3 codes. Quantum Inf. Comput. 6, 97–165 (2006).

Yamasaki, H. & Koashi, M. Time-efficient constant-space-overhead fault-tolerant quantum computation. Nat. Phys. 20, 247–253 (2024).

Kitaev, A. Y. Quantum computations: algorithms and error correction. Russ. Math. Surv. 52, 1191 (1997).

Kitaev, A. Fault-tolerant quantum computation by anyons. Ann. Phys. 303, 2–30 (2003).

Bravyi, S. B. & Kitaev, A. Y. Quantum codes on a lattice with boundary. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/quant-ph/9811052 (1998).

Litinski, D. A game of surface codes: large-scale quantum computing with lattice surgery. Quantum 3, 128 (2019).

Gottesman, D. Fault-tolerant quantum computation with constant overhead. Quantum Inf. Comput. 14, 1338–1372 (2014).

Bombín, H. Single-shot fault-tolerant quantum error correction. Phys. Rev. X 5, 031043 (2015).

Bravyi, S. et al. High-threshold and low-overhead fault-tolerant quantum memory. Nature 627, 778–782 (2024).

Fowler, A. G., Mariantoni, M., Martinis, J. M. & Cleland, A. N. Surface codes: towards practical large-scale quantum computation. Phys. Rev. A 86, 032324 (2012).

Breuckmann, N. P. & Eberhardt, J. N. Quantum low-density parity-check codes. PRX Quantum 2, 040101 (2021).

Leverrier, A., Tillich, J.-P. & Zémor, G. Quantum expander codes. In 2015 IEEE 56th Annual Symposium on Foundations of Computer Science (ed. O’Conner, L.) 810–824 (IEEE Computer Society, 2015).

Tillich, J. & Zémor, G. Quantum LDPC codes with positive rate and minimum distance proportional to the square root of the blocklength. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 60, 1193–1202 (2014).

Aharonov, D. & Ben-Or, M. Fault-tolerant quantum computation with constant error rate. SIAM J. Comput. 38, 1207–1282 (2008).

Knill, E., Laflamme, R. & Zurek, W. H. Resilient quantum computation: error models and thresholds. Proc. R. Soc. A 454, 365–384 (1998).

Reichardt, B. W. Fault-tolerance threshold for a distance-three quantum code. In Proc. 33rd International Conference on Automata, Languages and Programming (eds Bugliesi, M. et al.) 50–61 (Springer-Verlag, 2006).

Terhal, B. M. & Burkard, G. Fault-tolerant quantum computation for local non-Markovian noise. Phys. Rev. A 71, 012336 (2005).

Aliferis, P. & Preskill, J. Fault-tolerant quantum computation against biased noise. Phys. Rev. A 78, 052331 (2008).

Aliferis, P. & Terhal, B. M. Fault-tolerant quantum computation for local leakage faults. Quantum Inf. Comput. 7, 139–156 (2007).

Aliferis, P., Gottesman, D. & Preskill, J. Accuracy threshold for postselected quantum computation. Quantum Inf. Comput. 8, 181–244 (2008).

Preskill, J. Reliable quantum computers. Proc. R. Soc. A 454, 385–410 (1998).

Fawzi, O., Grospellier, A. & Leverrier, A. Constant overhead quantum fault-tolerance with quantum expander codes. In Proc. 2018 IEEE 59th Annual Symposium on Foundations of Computer Science (ed. Thorup, M.) 743–754 (IEEE, 2018).

Grospellier, A. Constant Time Decoding of Quantum Expander Codes and Application to Fault-Tolerant Quantum Computation. PhD thesis, Sorbonne Université (2019).

Fawzi, O., Grospellier, A. & Leverrier, A. Efficient decoding of random errors for quantum expander codes. In Proc. 50th Annual ACM SIGACT Symposium on Theory of Computing (eds Diakonikolas, I. et al.) 521–534 (ACM, 2018).

Knill, E. Scalable quantum computing in the presence of large detected-error rates. Phys. Rev. A 71, 042322 (2005).

Knill, E. Quantum computing with realistically noisy devices. Nature 434, 39–44 (2005).

Dennis, E., Kitaev, A., Landahl, A. & Preskill, J. Topological quantum memory. J. Math. Phys. 43, 4452–4505 (2002).

Terhal, B. M. Quantum error correction for quantum memories. Rev. Mod. Phys. 87, 307–346 (2015).

Caune, L. et al. Demonstrating real-time and low-latency quantum error correction with superconducting qubits. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2410.05202 (2024).

Acharya, R. et al. Quantum error correction below the surface code threshold. Nature 638, 920–926 (2025).

Bluvstein, D. et al. Logical quantum processor based on reconfigurable atom arrays. Nature 626, 58–65 (2023).

Moses, S. A. et al. A race-track trapped-ion quantum processor. Phys. Rev. X 13, 041052 (2023).

Ryan-Anderson, C. et al. Realization of real-time fault-tolerant quantum error correction. Phys. Rev. X 11, 041058 (2021).

Egan, L. et al. Fault-tolerant control of an error-corrected qubit. Nature 598, 281–286 (2021).

Bourassa, J. E. et al. Blueprint for a scalable photonic fault-tolerant quantum computer. Quantum 5, 392 (2021).

Litinski, D. & Nickerson, N. Active volume: an architecture for efficient fault-tolerant quantum computers with limited non-local connections. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2211.15465 (2022).

Yamasaki, H., Fukui, K., Takeuchi, Y., Tani, S. & Koashi, M. Polylog-overhead highly fault-tolerant measurement-based quantum computation: all-gaussian implementation with gottesman-kitaev-preskill code. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2006.05416 (2020).

Sunami, S., Tamiya, S., Inoue, R., Yamasaki, H. & Goban, A. Scalable networking of neutral-atom qubits: Nanofiber-based approach for multiprocessor fault-tolerant quantum computer. PRX Quantum 6, 010101 (2025).

Tremblay, M. A., Delfosse, N. & Beverland, M. E. Constant-overhead quantum error correction with thin planar connectivity. Phys. Rev. Lett. 129, 050504 (2022).

Xu, Q. et al. Constant-overhead fault-tolerant quantum computation with reconfigurable atom arrays. Nat. Phys. 20, 1084–1090 (2024).

Nguyen, Q. T. & Pattison, C. A. Quantum fault tolerance with constant-space and logarithmic-time overheads. In Proc. 57th Annual ACM Symposium on Theory of Computing (eds Koucký, M. & Bansal, N.) 730–737 (ACM, 2025).

Calderbank, A. R. & Shor, P. W. Good quantum error-correcting codes exist. Phys. Rev. A 54, 1098–1105 (1996).

Steane, A. Multiple particle interference and quantum error correction. Proc. R. Soc. A 452, 2551–2577 (1996).

Knill, E. & Laflamme, R. Concatenated quantum codes. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/quant-ph/9608012 (1996).

Gottesman, D. & Chuang, I. L. Demonstrating the viability of universal quantum computation using teleportation and single-qubit operations. Nature 402, 390–393 (1999).

Postler, L. et al. Demonstration of fault-tolerant universal quantum gate operations. Nature 605, 675–680 (2022).

Postler, L. et al. Demonstration of fault-tolerant Steane quantum error correction. PRX Quantum 5, 030326 (2024).

Yoshida, S., Tamiya, S. & Yamasaki, H. Concatenate codes, save qubits. NPJ Quantum Inf. 11, 88 (2025).

Draper, T. G. & Kutin, S. A. qpic. GitHub https://github.com/qpic/qpic (2016).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by JST (Moonshot R&D) under grant no. JPMJMS2061. S.T. was supported by JSPS KAKENHI (grant no. 23KJ0521) and FoPM, WINGS Program, the University of Tokyo. H.Y. acknowledges JST PRESTO (grant nos. JPMJPR201A and JPMJPR23FC), JSPS KAKENHI (grant no. JP23K19970) and MEXT Quantum Leap Flagship Program (MEXT QLEAP) (grant nos. JPMXS0118069605 and JPMXS0120351339). The quantum circuits shown in this Article were drawn using QPIC53.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.T., M.K. and H.Y. contributed to the conception of the work, the development and interpretation of the analysis, and the writing and editing of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Physics thanks Benjamin Brown and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figs. 1–19, Sections I–V and Appendix A.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tamiya, S., Koashi, M. & Yamasaki, H. Fault-tolerant quantum computation with polylogarithmic time and constant space overheads. Nat. Phys. 22, 27–32 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41567-025-03102-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41567-025-03102-5