Abstract

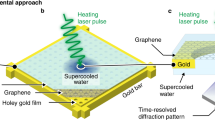

The fragile-to-strong transition in supercooled water, where the relaxation dynamics shift from non-Arrhenius to Arrhenius behaviour, has been hypothesized to explain its anomalous dynamic properties. However, this transition remains unresolved, as previous ultrafast experimental studies of bulk water dynamics were limited to temperatures far from the proposed transition due to rapid crystallization. Here we use an infrared laser pump and an ultrashort X-ray probe to measure the structural relaxation in micrometre-sized water droplets, evaporatively cooled at timescales ranging from femtoseconds to nanoseconds. Our experimental data show a dynamic crossover at around 233 K. Below this temperature, the relaxation dynamics deviate from simple power-law fits and follow a shallower temperature dependence. Molecular dynamics simulations successfully reproduce our findings.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$32.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $21.58 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Nilsson, A. & Pettersson, L. G. M. The structural origin of anomalous properties of liquid water. Nat. Commun. 6, 8998 (2015).

Li, S. et al. Attosecond-pump attosecond-probe X-ray spectroscopy of liquid water. Science 383, 1118–1122 (2024).

Angell, C. A., Sichina, W. J. & Oguni, M. Heat capacity of water at extremes of supercooling and superheating. J. Phys. Chem. 86, 998–1002 (1982).

Huang, C. et al. Increasing correlation length in bulk supercooled H2O, D2O, and NaCl solution determined from small angle X-ray scattering. J. Chem. Phys. 133, 134504 (2010).

Poole, P. H., Sciortino, F., Essmann, U. & Stanley, H. E. Phase behaviour of metastable water. Nature 360, 324–328 (1992).

Palmer, J. C. et al. Metastable liquid–liquid transition in a molecular model of water. Nature 510, 385–388 (2014).

Debenedetti, P. G., Sciortino, F. & Zerze, G. H. Second critical point in two realistic models of water. Science 369, 289–292 (2020).

Kim, K. H. et al. Maxima in the thermodynamic response and correlation functions of deeply supercooled water. Science 358, 1589–1593 (2017).

Kim, K. H. et al. Experimental observation of the liquid-liquid transition in bulk supercooled water under pressure. Science 370, 978–982 (2020).

Pathak, H. et al. Enhancement and maximum in the isobaric specific-heat capacity measurements of deeply supercooled water using ultrafast calorimetry. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 118, e2018379118 (2021).

Torre, R., Bartolini, P. & Righini, R. Structural relaxation in supercooled water by time-resolved spectroscopy. Nature 428, 296–299 (2004).

Taschin, A., Bartolini, P., Eramo, R., Righini, R. & Torre, R. Evidence of two distinct local structures of water from ambient to supercooled conditions. Nat. Commun. 4, 2401 (2013).

Dehaoui, A., Issenmann, B. & Caupin, F. Viscosity of deeply supercooled water and its coupling to molecular diffusion. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 112, 12020–12025 (2015).

Ito, K., Moynihan, C. T. & Angell, C. A. Thermodynamic determination of fragility in liquids and a fragile-to-strong liquid transition in water. Nature 398, 492–495 (1999).

Angell, C. A. Relaxation in liquids, polymers and plastic crystals—strong/fragile patterns and problems. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 131–133, 13–31 (1991).

Johari, G. P., Hallbrucker, A. & Mayer, E. The glass–liquid transition of hyperquenched water. Nature 330, 552–553 (1987).

Hallbrucker, A., Mayer, E. & Johari, G. P. The heat capacity and glass transition of hyperquenched glassy water. Philos. Mag. B 60, 179–187 (1989).

Amann-Winkel, K. et al. Water’s second glass transition. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 110, 17720–17725 (2013).

Sciortino, F., Gallo, P., Tartaglia, P. & Chen, S.-H. Supercooled water and the kinetic glass transition. Phys. Rev. E 54, 6331–6343 (1996).

De Marzio, M., Camisasca, G., Rovere, M. & Gallo, P. Microscopic origin of the fragile to strong crossover in supercooled water: the role of activated processes. J. Chem. Phys. 146, 084502 (2017).

Saito, S. Unraveling the dynamic slowdown in supercooled water: the role of dynamic disorder in jump motions. J. Chem. Phys. 160, 194506 (2024).

Shi, R., Russo, J. & Tanaka, H. Origin of the emergent fragile-to-strong transition in supercooled water. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 115, 9444–9449 (2018).

Xu, Y., Petrik, N. G., Smith, R. S., Kay, B. D. & Kimmel, G. A. Growth rate of crystalline ice and the diffusivity of supercooled water from 126 to 262 K. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 113, 14921–14925 (2016).

Sellberg, J. A. et al. Ultrafast X-ray probing of water structure below the homogeneous ice nucleation temperature. Nature 510, 381–384 (2014).

Abascal, J. L. F. & Vega, C. A general purpose model for the condensed phases of water: TIP4P/2005. J. Chem. Phys. 123, 234505 (2005).

Esmaeildoost, N. et al. Anomalous temperature dependence of the experimental X-ray structure factor of supercooled water. J. Chem. Phys. 155, 214501 (2021).

Cowan, M. L. et al. Ultrafast memory loss and energy redistribution in the hydrogen bond network of liquid H2O. Nature 434, 199–202 (2005).

Ramasesha, K., De Marco, L., Mandal, A. & Tokmakoff, A. Water vibrations have strongly mixed intra- and intermolecular character. Nat. Chem. 5, 935–940 (2013).

Markmann, V. et al. Real-time structural dynamics of the ultrafast solvation process around photo-excited aqueous halides. Chem. Sci. 15, 11391–11401 (2024).

Prat, E. et al. A compact and cost-effective hard X-ray free-electron laser driven by a high-brightness and low-energy electron beam. Nat. Photon. 14, 748–754 (2020).

Kim, K. H. et al. Anisotropic X-ray scattering of transiently oriented water. Phys. Rev. Lett. 125, 076002 (2020).

Kjær, K. S. et al. Introducing a standard method for experimental determination of the solvent response in laser pump, X-ray probe time-resolved wide-angle X-ray scattering experiments on systems in solution. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 15, 15003–15016 (2013).

Ihee, H. et al. Ultrafast X-ray diffraction of transient molecular structures in solution. Science 309, 1223–1227 (2005).

Ediger, M. D. Spatially heterogeneous dynamics in supercooled liquids. Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem. 51, 99–128 (2000).

Gallo, P. & Rovere, M. Mode coupling and fragile to strong transition in supercooled TIP4P water. J. Chem. Phys. 137, 164503 (2012).

De Marzio, M., Camisasca, G., Rovere, M. & Gallo, P. Mode coupling theory and fragile to strong transition in supercooled TIP4P/2005 water. J. Chem. Phys. 144, 074503 (2016).

Price, W. S., Ide, H. & Arata, Y. Self-diffusion of supercooled water to 238 K using PGSE NMR diffusion measurements. J. Phys. Chem. A 103, 448–450 (1999).

Angell, C. A. & Sare, E. J. Glass-forming composition regions and glass transition temperatures for aqueous electrolyte solutions. J. Chem. Phys. 52, 1058–1068 (1970).

Gallo, P. et al. Advances in the study of supercooled water. Eur. Phys. J. E 44, 143 (2021).

Tanaka, H. Simple physical model of liquid water. J. Chem. Phys. 112, 799–809 (2000).

Starr, F. W., Angell, C. A. & Stanley, H. E. Prediction of entropy and dynamic properties of water below the homogeneous nucleation temperature. Physica A 323, 51–66 (2003).

Caupin, F. Predictions for the properties of water below its homogeneous crystallization temperature revisited. J. Non-Cryst. Solids X 14, 100090 (2022).

Angell, C. A. Insights into phases of liquid water from study of its unusual glass-forming properties. Science 319, 582–587 (2008).

Xu, L. et al. Relation between the Widom line and the dynamic crossover in systems with a liquid–liquid phase transition. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 102, 16558–16562 (2005).

Singh, R. S., Biddle, J. W., Debenedetti, P. G. & Anisimov, M. A. Two-state thermodynamics and the possibility of a liquid-liquid phase transition in supercooled TIP4P/2005 water. J. Chem. Phys. 144, 144504 (2016).

Ingold, G. et al. Experimental station Bernina at SwissFEL: condensed matter physics on femtosecond time scales investigated by X-ray diffraction and spectroscopic methods. J. Synchrotron Radiat. 26, 874–886 (2019).

Knudsen, M. Die maximale Verdampfungsgeschwindigkeit des Quecksilbers. Ann. Phys. 352, 697–708 (1915).

Maa, J. R. Evaporation coefficient of liquids. Ind. Eng. Chem. Fundam. 6, 504–518 (1967).

Faubel, M., Schlemmer, S. & Toennies, J. P. A molecular beam study of the evaporation of water from a liquid jet. Z. Phys. D 10, 269–277 (1988).

Goy, C. et al. Refractive index of supercooled water down to 230.3 K in the wavelength range between 534 and 675 nm. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 13, 11872–11877 (2022).

Ishikawa, T. et al. A compact X-ray free-electron laser emitting in the sub-ångström region. Nat. Photon. 6, 540–544 (2012).

James, F. & Roos, M. Minuit—a system for function minimization and analysis of the parameter errors and correlations. Comput. Phys. Commun. 10, 343–367 (1975).

Abascal, J. L. F., Sanz, E., García Fernández, R. & Vega, C. A potential model for the study of ices and amorphous water: TIP4P/Ice. J. Chem. Phys. 122, 234511 (2005).

Abraham, M. J. et al. GROMACS: high performance molecular simulations through multi-level parallelism from laptops to supercomputers. SoftwareX 1–2, 19–25 (2015).

Saito, S., Bagchi, B. & Ohmine, I. Crucial role of fragmented and isolated defects in persistent relaxation of deeply supercooled water. J. Chem. Phys. 149, 124504 (2018).

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the Paul Scherrer Institute, Villigen, Switzerland, for provision of the free-electron laser beamtime under proposal p20794 at the Bernina instrument of the SwissFEL ARAMIS/ATHOS branch. This work is supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korea Government (MSIT) (grant numbers RS-2020-NR049542 and RS-2024-00348773) and by the Swedish Research Council (grant numbers VR-2013-8823, VR-2023-5080 and VR-2019-05542).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

K.H.K., A.N. and R.T. designed the study. K.H.K. and A.N. supervised the study. R.T. and M.S. led the experiment. R.T., M.S., S.Y., K.N., M.S., A.G., M.B., S.L., I.A., R.A.O., R.M., D.B., X.L., S.Z. and H.L. performed the SwissFEL experiments. M.S., R.T., S.Y., K.N., Y.H., S.J., F.P. and T.K. performed the SACLA experiments. M.S., R.T., F.P., A.N. and K.H.K. analysed the data. R.T., M.S., F.P., A.N. and K.H.K. wrote the paper with input from all authors.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Physics thanks Paola Gallo, Francesco Paesani and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Extended Data Fig. 1 Estimated temperature jump.

The laser induced temperature change is less than 1 K over the entire temperature range.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Failure of Single-Model Fits.

Fits of the temperature-dependent relaxation time to the functions associated with the different dynamic behaviors with entire temperature range. MCT (solid line) and the Arrhenius law (dashed-dotted line) are used. None of the functions associated with a single dynamic behavior can successfully explain the experimental result at lower temperatures. The error bars at each temperature point indicate the standard error determined from more than 10 independent measurements.

Extended Data Fig. 3 MD simulations of the FST.

(a) Temporal evolution of the magnitude of the difference scattering pattern (black squares) induced by a 1 K T-jump at 245 K calculated from MD simulations. The fit with the stretched exponential (red solid line) is shown. (b) Fitting results of the FST model to relaxation times extracted from MD simulations. At high temperatures, the dynamics follow a power-law dependence (red) and exhibit a transition to an Arrhenius behavior (blue) at around 238.7 K.

Extended Data Fig. 4 Comparison of measurements at SwissFEL and SACLA.

Comparison of measurements at two temperatures (265.0 K and 247.0 K) from SwissFEL (black) and SACLA (red). The nearly identical dynamics observed within the experimental error obtained from two different facilities indicate that our measurements are highly reproducible.

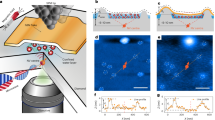

Extended Data Fig. 5 Single shot image of liquid water and ice.

A typical single shot image of (a) liquid water and (b) ice.

Extended Data Fig. 6 SVD analysis of time-resolved scattering data at 229.8 K.

(a) The singular values, (b) the autocorrelation values, (c) the left, and (d) the right singular vectors of the first three components are shown. In (c) and (d), horizontal dotted line indicates where the zero is. The analysis show that the first component represents the dominant time-dependent signal compared to the other components.

Extended Data Fig. 7 Left and right singular vectors at various temperatures.

(a) The left and (b) the right singular vectors of various temperatures ranging from 270.6 K to 228.3 K. In (b), linear and logarithmic time scales are used before and after 1 ps, respectively. As temperature decreases, structural relaxation significantly slows down.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Sections 1–7, Figs. 1–6 and Tables 1 and 2.

Source data

Source Data Fig. 1

Source data for Fig. 1.

Source Data Fig. 2

Source data for Fig. 2.

Source Data Fig. 3

Source data for Fig. 3.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Tyburski, R., Shin, M., You, S. et al. Observation of a dynamic transition in bulk supercooled water. Nat. Phys. 22, 21–26 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41567-025-03112-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41567-025-03112-3