Abstract

Introductions of species by humans are causing the homogenization of species composition across biogeographic barriers1,2,3. The ecological and evolutionary consequences of introduced species derive from their effects on networks of species interactions4,5, but we lack a quantitative understanding of the impacts of introduced species on ecological networks and their biogeographic patterns globally. Here we address this data gap by analysing mutualistic seed-dispersal interactions from 410 local networks, encompassing 24,455 unique pairwise interactions between 1,631 animal and 3,208 plant species. We show that species introductions reduce biogeographic compartmentalization of the global meta-network, in which nodes are species and links are interactions observed within any local network. This homogenizing effect extends across spatial scales, decreasing beta diversity among local networks and modularity within networks. The prevalence of introduced interactions is directly related to human environmental modifications and is accelerating, having increased sevenfold over the past 75 years. These dynamics alter the coevolutionary environments that mutualists experience6, and we find that introduced species disproportionately interact with other introduced species. These processes are likely to amplify biotic homogenization in future ecosystems7 and may reduce the resilience of ecosystems by allowing perturbations to propagate more quickly and exposing disparate ecosystems to similar drivers. Our results highlight the importance of managing the increasing homogenization of ecological complexity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Natural barriers to dispersal underlie differences in species composition across biogeographic regions8,9. Accelerating trade and transportation are breaking down these barriers, increasing the prevalence of species introductions over time3 and causing the homogenization of the species composition across historical biogeographic regions1,2. The ecological network approach provides tools to understand the ecological and evolutionary consequences of introduced species within individual ecosystems6,10. However, the global scope of the impacts of introduced species on ecological networks and their biogeographic patterns remain unquantified.

A key plant–animal mutualism involves fleshy-fruited plants and the animals that disperse their seeds11. This plant–frugivore mutualism shapes biodiversity within and among ecosystems12,13, and its coevolution has driven the diversification of species and their traits14,15. Animal-mediated dispersal of seeds is influenced by drivers of global change that include defaunation, species invasion and habitat fragmentation16. In particular, declines of large vertebrates have been linked to declines in plant populations and have redirected the evolution of traits17,18,19. Introduced species have invaded local plant–frugivore networks5 and in some ecosystems largely replaced network roles that were missing owing to the loss of native species10. Animal-mediated seed dispersal also affects how ecosystems respond to global change; roughly half of all plant species depend on movement by animals for the range shifts required to keep pace with climate change20,21. Hence, anthropogenic impacts on plant–frugivore networks will shape the trajectory of future terrestrial ecosystems, highlighting the importance of research to understand the severity of these impacts.

To develop a quantitative understanding of the impacts of species introductions on the plant–frugivore mutualism globally, we assembled network data from the literature. The data derive from 410 local networks in which plant–frugivore interactions were observed at a given location and temporal period, typically by directly observing animals foraging or by recovering seeds from captured animals. In the local bipartite networks, each node represents a plant or animal species, and edges represent the observation of a pairwise interaction. We considered only plants and animals identified to the species level, resolved naming issues and incorporated taxonomic revisions that have occurred since the data were collected. This approach identified 24,455 unique interactions between species pairs that involved 1,631 animal and 3,208 plant species. Three-quarters of the reported interactions were with birds, and the remainder were mostly with mammals, primarily bats and primates; only 1% of interactions involved lizards, tortoises or fish. By combining these interaction data with data on the native or introduced status of plants and animals at the study locations, we were able to assess introduced interactions in which either the plant or animal was an introduced species. By assessing shared species-level nodes between local networks, we constructed global meta-networks encompassing all species and the interactions between them observed at any study location.

To assess how species introductions have altered biogeographic network signatures, we compared a meta-network constructed using local networks from which introduced species were removed (that is, with only native interactions; Fig. 1a) to the meta-network constructed using all interactions observed within the local networks (Fig. 1b). As in similar analyses focused on species composition2, we avoid biases due to heterogeneous sampling coverage by interpreting relative differences between patterns observed with and without anthropogenic introductions. When only native interactions were considered(Fig. 1a), clear biogeographic compartmentalization of the global meta-network emerged, even with no spatial data having entered the analysis, broadly mirroring historical bioregions that have commonly been identified through the assessment of species occurrence9 (Fig. 1c). This application of ecological network data recapitulates the importance of historical dispersal barriers to biogeographic patterns9 and demonstrates the degree of biotic connectivity across regions, which is likely to have influenced spatial heterogeneity in plant–frugivore coevolution across deep temporal scales22. In the observed meta-network, interactions with introduced species blurred these natural biogeographic patterns, significantly reducing compartmentalization among bioregions (Fig. 1b; bootstrapped z = 4.03, P = 5.5 × 10−5). Comparing the native-only and observed meta-networks to meta-networks simulated under a null model reflecting complete homogenization of interactions within biomes indicated that introduced interactions have decreased biogeographic compartmentalization by 8.5% (Extended Data Fig. 1). This loss of a biogeographic pattern is not explained by the lower number of interactions in the native-only meta-network, as repeating the analysis using a null model that randomly removed interactions from the observed meta-network to reduce the number of interactions to that for the native-only network yielded modularity values that were similar to those in the observed meta-network (Extended Data Fig. 1; bootstrapped z = 0.15, P = 0.88). These results indicate that species introductions are eroding the natural signatures of biogeography across the global plant–frugivore meta-network.

a, b, Meta-networks including native interactions only (a) or both native and introduced interactions (b). Each node represents a plant or animal species, and links represent interactions observed at any study location. c, Interaction data derived from 410 spatially or temporally distinct networks, coloured on the basis of their assignment to bioregions and oceanic islands. d, The degree of separation among species pairs in the meta-network is greater when only interactions among native species are considered than when interactions with introduced species are included. e, Closeness centrality for each species is higher in the observed meta-network that includes introduced interactions than in the native-only meta-network. Points represent species; line and shading show standardized major-axis regression fit and confidence interval.

Species introductions are causing the meta-network to exhibit ‘small world’ properties23. Introduced interactions have reduced the degrees of separation between any two plant and animal nodes in the connected component of the meta-network from roughly seven to five on average (Fig. 1d). This increased the closeness centrality of species by more than one-third (SMA slope 1.37, r = 0.40, d.f. = 4,429, P < 2 × 10−16; Fig. 1e). Species introductions have also reduced the diameter of the network, measured as the greatest degree of separation that existed between species pairs, from 17 to 13. Whereas roughly 2% of species in the native-only meta-network were in disconnected components representing endemic networks, only 0.17% remained disconnected when introduced interactions were included (Fig. 1a, b). Theory indicates that these outcomes—novel direct interactions and closer indirect interactions—underlie the evolution of trait convergence in mutualistic networks6. This occurs through introductions imposing similar selection gradients over space6, with the effect further strengthened if gene flow into the introduced species occurs through recurrent introductions24. The changes to the meta-network that we documented may thus cause functional homogenization within local networks by altering the coevolutionary trajectories of plants and frugivores.

Having explored how species introductions have altered patterns of biogeography and indirect interactions across the meta-network, we next examined shared network elements across bioregions and beta diversity across local networks. The proportion of regions that shared species and interactions, and the proportion of species and interactions that they share, has increased as a result of species introductions (Fig. 2; Extended Data Table 1). Shared interactions across bioregions can be caused by natural co-occurrences in multiple bioregions or by anthropogenic co-introductions (for example, a bird and plant species from Europe both introduced to New Zealand: common hawthorn–song thrush, Crataegus monogyna–Turdus merula), reciprocal introductions (for example, a bird from Europe to North America and plant from North America to Europe: American pokeweed–European starling, Phytolacca americana–Sturnus vulgaris) or replicated novel interactions between species from two distinct regions both introduced to other regions (for example, a bird from Asia and plant from South America introduced to both Hawaii and Tahiti; Brazilian peppertree–red-vented bulbul, Schinus terebinthifolia–Pycnonotus cafer). Such introductions partially decouple the beta diversity relationship of decreasing species and interaction similarity between more distant sampling locations25 (Extended Data Fig. 2). Increasing similarity of network composition over space may reduce stability at large spatial scales by synchronizing responses to widespread perturbations such as climate change or novel pathogens26.

Points represent the number of species or interactions observed in each bioregion or oceanic island system, with the point’s coordinates at the centroid of the study locations for each region. The thickness of lines, plotted along great circles, shows the proportion of shared species or interactions between bioregions or oceanic island systems. Note the long arcs in the right column connecting Europe to New Zealand to the east and the Azores to New Zealand to the west.

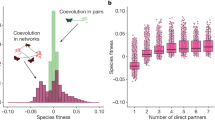

At the local network scale, we assessed how introduced species interact and affect the network structure. Suggesting that introduced plant–frugivore interactions may facilitate invasional meltdown27, introduced plants and animals were twice as likely as native species to interact with introduced partners present within their local network (Fig. 3a; χ2a = 15.8, d.f. = 1, Pa = 6.9 × 10−5, χ2p = 13.6, d.f. = 1, Pp = 2.3 × 10−4, where subscripts a and p refer to animals and plants, respectively; Extended Data Table 2). We also tested the prediction that mutualists that are naturally more interactive are more likely to become established. Considering species only where they are native, we found that the normalized degree—the number of partners divided by the number of potential partners—was greater for species that are known to have been introduced elsewhere than for species that have not been reported as introduced; this effect was statistically significant but small for plants and larger for animals (Extended Data Fig. 3; all P ≤ 0.0002; Extended Data Table 3). Introduced species homogenized the structure of local networks by reducing their modularity (Fig. 3b; Extended Data Fig. 4; χ2 = 7.0, d.f. = 1, P = 0.008), an effect that was not explained by other factors such as differences between island and mainland networks, study design or network connectance (Extended Data Table 4). Theory indicates that reduced modularity can limit stability by allowing perturbations to directly and indirectly affect a larger portion of the community; with greater modularity, species-specific effects of disturbance such as overexploitation or pest outbreaks can be isolated within modules28. Together, these analyses show that introduced species disproportionately develop mutualistic relationships with other introduced species and influence network stability by homogenizing their structure.

a, In networks where focal animals and plants have potential partners that are introduced, introduced animals and plants are significantly more likely to interact with introduced partners; bars indicate binomial GLMM model estimates (± s.e.m.). b, Number of discrete modules within local networks that vary within the proportion of interactions involving an introduced species, with points jittered.

Finally, we sought to understand the factors that explained the prevalence of introduced species and interactions within local plant–frugivore networks over time and space. The prevalence of introduced interactions has increased over time (Fig. 4a; GLMM likelihood ratio test χ2 = 106.3, d.f. = 1, P < 2 × 10−16; Extended Data Table 5) and is approximately seven times higher in the most recent than in the earliest recorded networks. Introduced interactions were also more prevalent in areas of greater human modification of the environment29 (Fig. 4b; χ2 = 414.2, d.f. = 1, P < 2 × 10−16; Extended Data Table 5), being approximately eight times more frequent in the most versus the least modified environments. We assessed these relationships using mixed-effects models that accounted for regional differences in introduction dynamics. To assess the robustness of these results, we assessed the influence of several potential biases. First, the pattern over time could be influenced by the focal taxa that researchers targeted for observation (for example, by earlier researchers excluding introduced species from observation). Yet using a more conservative set of local networks in which all potential interactions were observed and reported (not just those for a target subset of plant and/or animal species) yielded a qualitatively identical relationship (χ2 = 50.7, d.f. = 1, P = 1.1 × 10−12). Second, the temporal pattern could be influenced by the locations chosen for study (for example, by earlier researchers focusing on less anthropogenically affected habitats). Study year remained a highly statistically significant predictor in models that accounted for variation in human modification values, however, which indicated that the temporal pattern is not a spurious result of the choice of study site (Extended Data Table 6). Third, heterogeneous human modification over time could introduce bias in the relationship between the proportion of introduced interactions and estimates of human modification, which characterize conditions around 201629. A reanalysis using only local networks collected after 2000 or after 2010, however, showed qualitatively identical relationships (χ22000 = 320.6, d.f. = 1, P2000 < 2 × 10−16, χ22010 = 106.6, d.f. = 1, P2010 < 2 × 10−16). Furthermore, the proportion of introduced species, and of interactions caused by an introduced plant or animal species, was higher for oceanic island systems than for continental bioregions (Fig. 4c). These impacts on mutualistic networks reflect the particular susceptibility of remote islands to invasion and loss of native species5. Networks from large continental bioregions typically had few introduced animals and a greater prevalence of introduced plants than animals. Together, these results demonstrate quantitatively that, over time, the global plant–frugivore mutualism increasingly consists of introduced interactions, especially on islands and in ecosystems that have undergone relatively greater anthropogenic environmental modifications.

a, b, The proportion of introduced interactions recorded shows an accelerating trajectory over time (a) and is related to human modification of the environment (b). Lines indicate binomial GLMM model estimates; grey areas indicate prediction intervals. c, The proportions of introduced animal species, plant species and interactions are typically higher on oceanic island systems than in continental bioregions. Unfilled points represent cases in which zero introduced species or interactions were recorded.

This work offers a global quantitative synthesis that shows—for a key type of mutualism—the impacts of introduced species on interaction networks and the biogeography of interactions. At the first time point for which sufficient data exist to characterize the global meta-networks, species introductions have already substantially eroded natural biogeographic signatures that developed over millions of years. The cross-scale changes to the plant–frugivore mutualism reflect the disruption of evolutionary and ecological processes that are likely to shape the biodiversity and resilience of future terrestrial ecosystems. The widespread impacts and disproportionate facilitation among introduced species demonstrated here, combined with the importance of plant–frugivore interactions in determining which plant species will keep pace with climate change21 and contribute to forest restoration30, suggests that plant–frugivore networks are likely to increasingly favour a relatively few introduced generalists over many native species7, reducing the uniqueness of future biotas. Our results highlight the importance of research to understand the contributions of species to functional and phylogenetic homogenization, as well as careful management of species introductions to limit the loss of biodiversity in ecological networks.

Methods

Plant–frugivore network data

We used data from 410 networks derived from 241 studies (study IDs and references available in the Dryad data repository; see ‘Data availability’), considering as individual networks those at the finest spatial and temporal scale that the network data were reported. To assemble this database, we extensively searched the literature for networks of interactions between vertebrates and fleshy-fruited plants. We started with network studies incorporated in previous syntheses of plant–frugivore networks31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40, found relevant studies that cited or were cited by those primary network studies, and supplemented this process with web searches to find additional studies. We incorporated all networks we were able to find through April 2019, excluding networks with plant or animal taxa only identified above the species level. We recorded metadata on the focal taxa that were the target of observation (for example, birds, bats), whether the observation and reporting covered all or a subset of the focal taxa (for example, observing only a target list of plant species or only reporting interactions with a subset of frugivore species), coordinates for the study site, and the study year (mean year of data collection or publication year if not reported). We assigned local networks to regions according to the 11 broad realms identified by Holt et al.9, with the exception of island systems (Azores, Canary Islands, Galapagos, Hawaiian Islands, Mariana Islands, New Zealand, Seychelles, Society Islands), each of which we treat as separate regions for visualization and analysis.

To ensure that consistent species names were used across all local networks, we standardized taxonomy following ITIS (Integrated Taxonomic Information System; http://www.itis.gov) for animals and The Plant List (http://www.theplantlist.org) for plants. Most issues involved typos or synonyms, which we corrected using the ‘Taxonstand’ R package41 and The Taxonomic Name Resolution Service (http://tnrs.iplantcollaborative.org)42. In some cases, species have had taxonomic revisions since the study’s publication, typically scenarios such as one previously recognized bird species now split into two recognized species. In these cases, we used the study location to associate the observed taxon with its current accepted name. We did not encounter ambiguities where taxa that are now split are sympatric at the study location.

We determined whether species were native or introduced within local networks, focusing on identifying human-mediated introductions across regions. For animals, we used country-level data on the native or introduced status from IUCN (http://www.iucnredlist.org). For plants, we used country-level data from Plants of the World Online (POWO; http://www.plantsoftheworldonline.org), which provides information on countries in which plant species have been reported as native or introduced, and from the Global Register of Introduced and Invasive Species (GRIIS; http://www.griis.org), which gives information on introduced species presence by country. If a plant did not have a status assignment for the country where the network was recorded, we considered it native if it was recorded as native in a nearby country (for example, reported native in Honduras and Costa Rica but no status assignment for Nicaragua). When we were unable to assign the status for species with these approaches using the global databases, we used information from the studies themselves or species lists from the study location to assess native or introduced status. Although we generally adopted a country-level focus, we considered separately disjunct sub-national entities, particularly islands, in relevant cases (for example, Galapagos versus mainland Ecuador). Focusing at the country level allowed us to match the scales of data available for plants and animals while emphasizing longer-scale anthropogenic introductions rather than shorter-scale movement or range expansion. Considering data reported in all networks over the past 75 years, 7% of interactions among accepted plant and animal species involved an introduced species and 1% involved an introduced plant and introduced animal.

Global meta-networks

We developed a global meta-network comprised of all observed interactions (including both native and introduced interactions) by constructing a binary adjacency matrix describing all species interactions recorded in any local network. We also constructed a global meta-network containing only native interactions by doing so after removing from local networks species that are introduced at the local network’s location. This approach mirrors studies that have removed species identified as introduced from contemporary species lists to assess the impact of species introductions on species-level biogeographic patterns2 or from local mutualistic networks to assess how they alter local network structure43,44. We use the term ‘meta-network’ to describe, as a single network, all realized interactions observed in any of multiple local networks following terminology of recent studies45,46,47. The term ‘metaweb’ has been used for this concept primarily in the context of food webs48. We visualized the meta-networks using a Fruchterman–Reingold layout with the ‘ggnetwork’ package in R49. All maps were produced using the ‘maps’ package in R50.

To determine statistically how introduced interactions have altered the meta-network’s compartmentalization along biogeographic regions, we used a bootstrapping approach. In each bootstrap iteration, we resampled with replacement the pairwise interactions and developed an adjacency matrix as above for the native-only meta-network and the meta-network including introduced interactions. We assigned module membership to species according to the bioregions or oceanic island systems in which they appeared as native, sampling one per species per iteration. Calculating unipartite modularity (Q) following Clauset et al.51 in the R package ‘igraph’52, we took the difference in modularity among the native-only meta-network and the meta-network involving introduced interactions. Using 200 iterations, we calculated a P value (two-sided, as in all other analyses) with the resulting z score. Because the native-only meta-network has fewer interactions, we tested whether the difference in modularity was a spurious result of the lower number of interactions. To test this, we randomly removed interactions probabilistically from the resampled meta-network including introduced interactions, achieving on average the equivalent number of interactions as in the resampled native-only meta-network. We similarly calculated a z score and P value to assess whether modularity differed in this reduced meta-network versus the meta-network including introduced interactions. Lastly, we sought to understand how much biogeographic compartmentalization has decreased relative a scenario of complete biotic homogenization. For each resampled meta-network including introduced interactions, we randomized interactions among species present within each biome, using biomes defined by Dinerstein et al.53. By allowing random interactions within biomes, this null model reflects a scenario of highly homogenized interactions in which species occurrence is only constrained by abiotic filters, not dispersal barriers. We calculated the loss of biogeographic compartmentalization using the modularity of the native-only meta-network (Qnative), of the observed meta-network including introduced interactions (Qobserved), and of the meta-network with interactions randomized within biomes (Qrand) as (Qnative – Qobserved)/(Qnative – Qrand). We also used the igraph package to calculate network diameter, the pairwise distances (degrees of separation) between nodes, and closeness centrality for species in the connected component of the network. We calculated closeness centrality (CC) as

where dij is the shortest path length between species i and species j and n is the number of species. For species present in the connected component of the native-only meta-network and meta-network including introduced interactions (n = 4,431), we used standardized major axis regression to assess how closeness centrality of species has changed with species introductions, testing the null hypothesis that the slope equals 1 in the R package ‘smatr’54.

Quantifying diversity between regions and networks

To visualize how species introductions have altered patterns of shared species composition over space, we calculated the proportion of shared species and interactions across all pairs of regions, whether continental bioregions or oceanic island systems. We calculated this as the intersection of the sets of species (or interactions) in each pair of regions divided by the union of these sets. We used GLMMs in the R package ‘lme4’55 to analyse how species introductions influence (1) the proportion of region pairs sharing network elements (species and interactions) and (2) the proportion of their elements that was shared. The binomial response variables described (1) whether the region pair had shared plant species, animal species or interactions, or (2) the proportion of shared elements out of the total number of elements observed in the region pair. The predictor variable described these values calculated when considering native species and interactions only or all species and interactions. We allowed random intercepts by region pair ID. To quantify beta diversity across these networks, we used the ‘betalink’ package in R25 to calculate pairwise similarity in the species composition (1 – βS) and the similarity of interactions (1 – βWN). In these analyses, we made comparisons only among pairs of networks constructed to target the same group of animals. For example, we compared local networks that targeted bats with other local networks targeting bats, but did not assess beta diversity between bird-focused and bat-focused local networks. We calculated pairwise similarities only among local networks targeting birds, bats, primates, mammalian carnivores, and mammalian herbivores. We used generalized additive models to fit the relationship between distance separating network pairs and both 1 – βS and 1 – βWN using local networks as they were observed (including introduced interactions) versus local networks where introduced species were removed (native interactions only).

Processes within local networks

We used several analyses to characterize how introduced species interact within local networks and influence local network structure. First, we sought to determine if introduced species are more likely to interact with introduced than native partners. In separate GLMMs for plants and animals, the binomial response variable described the proportion of a focal species’ interactions that are with introduced partners versus the proportion that are with native partners. The predictor variable was whether the focal species was itself a native or introduced species. These analyses were only performed using networks where the focal taxon had one or more potential partner that was introduced. We allowed random intercepts by region and local network ID, using likelihood ratio tests against null models as in other analyses. Because this analysis focuses on interactions between focal species and their potential partners within their local network, it avoids the potential for biased results caused by a positive relationship between the number of introduced plant and animal species within local networks.

Second, we sought to quantify whether plants that become established as introduced species are naturally more or less interactive than species that do not appear as introduced species. In these analyses, we only consider interaction patterns for species observed in local networks within their native range. We repeated analyses using two approaches for attributing species as introduced species, either by considering introduced species to be those that are reported as introduced anywhere in any of the publicly available databases described above (IUCN, POWO, GRIIS) or by considering introduced species to be those that appear as introduced species in local networks outside their native range in our database. In the analyses, the binomial response variable was the proportion of partners within the local network that the focal species was observed interacting with versus those it did not interact with; this describes normalized degree. The predictor variable was whether the species appears as introduced. As in the other analyses, we used random intercepts by region and local network ID and performed likelihood ratio tests in separate models for animals and plants.

Third, we examined modularity within local networks. We report the number of true compartments calculated using the ‘compart’ function in the ‘bipartite’ package in R56. We assessed how the proportion of introduced interactions within local networks impacts modularity while accounting for other network structural attributes that can influence modularity and its detection by analysing null model-corrected modularity. To do so, we compare observed modularity to the modularity of corresponding networks generated under a null model57 designed to maintain the degree distribution of the observed network. We calculated null model-corrected modularity of each local network as the observed modularity minus the average modularity of five corresponding null networks. To obtain modularity values, we used the hybrid spectral partitioning + simulated annealing algorithm in the program MODULAR58 to determine bipartite modularity optimized via the Newman and Girvan 2004 metric59. We calculated modularity for the 395 networks with at least two species at each trophic level and in which at least one species had at least two partners. In a linear mixed effects model, null model-corrected modularity was the response variable, the proportion of the local networks’ interactions that involved introduced species (that is, proportion introduced interactions) was the predictor variable, and we allowed random intercept by study location. We assessed statistical significance using a likelihood ratio test against an intercept-only model. For visualization, we use mixed effects quantile regression with the same model formulation to visualize the 5th, 50th, and 95th percentiles with the ‘lqmm’ package in R60. To assess whether other factors better explained differences in null model corrected modularity, we compared AIC among all combinations of models with fixed effects of the proportion of interactions involving an introduced species, connectance, the number of target groups studied (birds, bats, primates, carnivores, herbivores, other non-flying mammals, fish, reptiles), and if the local network was from an oceanic island system.

Spatiotemporal impacts of introduced species and interactions

To assess the prevalence of introduced species interactions over time, we used GLMMs with the binomial response variable describing the proportion of the local network’s species interactions that are introduced versus the proportion that are native (involving both a native plant and native animal species). The predictor variable was study year and we allowed random intercepts by region. To assess statistical significance, we used a likelihood ratio test against an intercept-only model. To assess the relationship between human environmental impact and prevalence of introduced interactions, we used the same approach except with gHM values29 as the single predictor variable. This index characterizes the cumulative severity of human modification in terrestrial environments on a scale between 0 and 1 with a 1 km2 resolution. We calculated the mean gHM value within a 5 km buffer of the study and similarly used a likelihood ratio test against a null model to assess statistical significance. We performed several robustness checks. First, we performed similar analyses and likelihood ratio tests to assess the relationship with study year for local networks that were designed to observe and reported interactions between all plant species and all bird species, all bat species, or all primate species. Second, to confirm that year and gHM are independently related to the prevalence of introduced interactions, independent of any modification-biased site selection over time, we compared AIC between a full model including study year, gHM, and their interaction and all the nested models. Third, we analysed the relationship with gHM values, which are calculated to represent ~2016, for local networks collected after 2000 or 2010.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this paper.

Data availability

All data used in the analyses are available through the Dryad digital data repository (https://doi.org/10.5061/dryad.44j0zpcbx).

Code availability

All scripts that are needed to reproduce the analyses and figures are available through the Dryad digital data repository (https://doi.org/10.5061/dryad.44j0zpcbx).

References

Helmus, M. R., Mahler, D. L. & Losos, J. B. Island biogeography of the Anthropocene. Nature 513, 543–546 (2014).

Capinha, C., Essl, F., Seebens, H., Moser, D. & Pereira, H. M. Biogeography. The dispersal of alien species redefines biogeography in the Anthropocene. Science 348, 1248–1251 (2015).

Seebens, H. et al. No saturation in the accumulation of alien species worldwide. Nat. Commun. 8, 14435 (2017).

David, P. et al. Impacts of invasive species on food webs: a review of empirical data. Adv. Ecol. Res. 56, 1–60 (2017).

Traveset, A. & Richardson, D. M. Mutualistic interactions and biological invasions. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 45, 89–113 (2014).

Guimarães, P. R. Jr, Pires, M. M., Jordano, P., Bascompte, J. & Thompson, J. N. Indirect effects drive coevolution in mutualistic networks. Nature 550, 511–514 (2017).

McKinney, M. L. & Lockwood, J. L. Biotic homogenization: a few winners replacing many losers in the next mass extinction. Trends Ecol. Evol. 14, 450–453 (1999).

Wallace, A. R. The Geographical Distribution of Animals and Plants (Harper & Brothers, 1876).

Holt, B. G. et al. An update of Wallace’s zoogeographic regions of the world. Science 339, 74–78 (2013).

Vizentin-Bugoni, J. et al. Structure, spatial dynamics, and stability of novel seed dispersal mutualistic networks in Hawai’i. Science 364, 78–82 (2019).

Jordano, P. in Seeds: The Ecology of Regeneration in Plant Communities 2nd edn (ed. Fenner, M.) 18–61 (CABI, 2000).

Nathan, R. & Muller-Landau, H. C. Spatial patterns of seed dispersal, their determinants and consequences for recruitment. Trends Ecol. Evol. 15, 278–285 (2000).

Herrera, C. M. in Plant–Animal Interactions: An Evolutionary Approach (eds Herrera, C. M. & Pellmyr, O.) 185–208 (Blackwell, 2002).

Jordano, P. Patterns of mutualistic interactions in pollination and seed dispersal: connectance, dependence asymmetries, and coevolution. Am. Nat. 129, 657–677 (2002).

Tiffney, B. H. Vertebrate dispersal of seed plants through time. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 35, 1–29 (2004).

McConkey, K. R. et al. Seed dispersal in changing landscapes. Biol. Conserv. 146, 1–13 (2012).

Terborgh, J. et al. Tree recruitment in an empty forest. Ecology 89, 1757–1768 (2008).

Galetti, M. et al. Functional extinction of birds drives rapid evolutionary changes in seed size. Science 340, 1086–1090 (2013).

Rogers, H. S. et al. Effects of an invasive predator cascade to plants via mutualism disruption. Nat. Commun. 8, 14557 (2017).

Aslan, C. E., Zavaleta, E. S., Tershy, B. & Croll, D. Mutualism disruption threatens global plant biodiversity: a systematic review. PLoS One 8, e66993 (2013).

Schleuning, M. et al. Ecological networks are more sensitive to plant than to animal extinction under climate change. Nat. Commun. 7, 13965 (2016).

Thompson, J. The Geographic Mosaic of Coevolution (Univ. Chicago Press, 2005).

Watts, D. J. & Strogatz, S. H. Collective dynamics of ‘small-world’ networks. Nature 393, 440–442 (1998).

Medeiros, L. P., Garcia, G., Thompson, J. N. & Guimarães, P. R. Jr. The geographic mosaic of coevolution in mutualistic networks. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 115, 12017–12022 (2018).

Poisot, T., Canard, E., Mouillot, D., Mouquet, N. & Gravel, D. The dissimilarity of species interaction networks. Ecol. Lett. 15, 1353–1361 (2012).

Wang, S. & Loreau, M. Biodiversity and ecosystem stability across scales in metacommunities. Ecol. Lett. 19, 510–518 (2016).

Simberloff, D. & Von Holle, B. Positive interactions of nonindigenous species: invasional meltdown? Biol. Invasions 1, 21–32 (1999).

Tylianakis, J. M., Laliberté, E., Nielsen, A. & Bascompte, J. Conservation of species interaction networks. Biol. Conserv. (2010).

Kennedy, C. M., Oakleaf, J. R., Theobald, D. M., Baruch-Mordo, S. & Kiesecker, J. Managing the middle: a shift in conservation priorities based on the global human modification gradient. Glob. Chang. Biol. 25, 811–826 (2019).

Bastin, J.-F. et al. The global tree restoration potential. Science 365, 76–79 (2019).

Rezende, E. L., Lavabre, J. E., Guimarães, P. R., Jordano, P. & Bascompte, J. Non-random coextinctions in phylogenetically structured mutualistic networks. Nature 448, 925–928 (2007).

Mello, M. A. R. et al. The missing part of seed dispersal networks: structure and robustness of bat-fruit interactions. PLoS One 6, e17395 (2011).

Schleuning, M. et al. Ecological, historical and evolutionary determinants of modularity in weighted seed-dispersal networks. Ecol. Lett. 17, 454–463 (2014).

Chen, S. C. & Moles, A. T. A mammoth mouthful? A test of the idea that larger animals ingest larger seeds. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 24, 1269–1280 (2015).

Dalsgaard, B. et al. Opposed latitudinal patterns of network-derived and dietary specialization in avian plant–frugivore interaction systems. Ecography 40, 1395–1401 (2016).

de Assis Bomfim, J., Guimarães, P. R., Peres, C. A., Carvalho, G. & Cazetta, E. Local extinctions of obligate frugivores and patch size reduction disrupt the structure of seed dispersal networks. Ecography 41, 1899–1909 (2018).

Castaño, J. H., Carranza, J. A. & Pérez-Torres, J. Diet and trophic structure in assemblages of montane frugivorous phyllostomid bats. Acta Oecol. 91, 81–90 (2018).

Escribano-Avila, G., Lara-Romero, C., Heleno, R. & Traveset, A. in Ecological Networks in the Tropics (eds Dáttilo, W. & Rico-Gray, V.) 93–110 (Springer, 2018).

Laurindo, R. S., Novaes, R. L. M., Vizentin-Bugoni, J. & Gregorin, R. The effects of habitat loss on bat-fruit networks. Biodivers. Conserv. 28, 589–601 (2019).

Dugger, P. J. et al. Seed-dispersal networks are more specialized in the Neotropics than in the Afrotropics. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 28, 248–261 (2019).

Cayuela, L., Granzow-de la Cerda, Í., Albuquerque, F. S. & Golicher, D. J. Taxonstand: an R package for species names standardisation in vegetation databases. Methods Ecol. Evol. 3, 1078–1083 (2012).

Boyle, B. et al. The taxonomic name resolution service: an online tool for automated standardization of plant names. BMC Bioinformatics 14, 16 (2013).

Trøjelsgaard, K., Heleno, R. & Traveset, A. Native and alien flower visitors differ in partner fidelity and network integration. Ecol. Lett. 22, 1264–1273 (2019).

Aslan, C. E. Implications of non-native species for mutualistic network resistance and resilience. PLoS One 14, e0217498 (2019).

Araujo, A. C. et al. Spatial distance and climate determine modularity in a cross-biomes plant–hummingbird interaction network in Brazil. J. Biogeogr. 45, 1846–1858 (2018).

Emer, C. et al. Seed-dispersal interactions in fragmented landscapes—a metanetwork approach. Ecol. Lett. 21, 484–493 (2018).

Nnakenyi, C. A., Traveset, A., Heleno, R., Minoarivelo, H. O. & Hui, C. Fine-tuning the nested structure of pollination networks by adaptive interaction switching, biogeography and sampling effect in the Galápagos Islands. Oikos 128, 1413–1423 (2019).

Dunne, J. A. in Ecological Networks: Linking Structure to Dynamics in Food Webs (eds Pascual, M. & Dunne, J. A.) 27–86 (Oxford Univ. Press, 2006).

Briatte, F. ggnetwork: geometries to plot networks with ‘ggplot2’. R package v.0.5.1. (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2016).

Becker, R. A., Wilks, A. R., Brownrigg, R., Minka, T. P. & Deckmyn, A. maps: draw geographical maps. R package v.3 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2013).

Clauset, A., Newman, M. E. J. & Moore, C. Finding community structure in very large networks. Phys. Rev. E. 70, 066111 (2004).

Csardi, G. & Nepusz, T. The igraph software package for complex network research. InterJournal 1695 (2006).

Dinerstein, E. et al. An ecoregion-based approach to protecting half the terrestrial realm. Bioscience 67, 534–545 (2017).

Warton, D. I., Duursma, R. A., Falster, D. S. & Taskinen, S. smatr 3—an R package for estimation and inference about allometric lines. Methods Ecol. Evol. 3, 257–259 (2012).

Bates, D., Mächler, M., Bolker, B. & Walker, S. Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. J. Stat. Softw. 67, 1–48 (2015).

Dormann, C. F., Gruber, B. & Fründ, J. Introducing the bipartite package: analysing ecological networks. Interaction 1, 0.2413793 (2008).

Bascompte, J., Jordano, P., Melián, C. J. & Olesen, J. M. The nested assembly of plant-animal mutualistic networks. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 100, 9383–9387 (2003).

Marquitti, F. M. D., Guimarães, P. R., Pires, M. M. & Bittencourt, L. F. MODULAR: software for the autonomous computation of modularity in large network sets. Ecography 37, 221–224 (2014).

Newman, M. E. J. & Girvan, M. Finding and evaluating community structure in networks. Phys. Rev. E 69, 026113 (2004).

Geraci, M. Linear quantile mixed models: the lqmm package for Laplace quantile regression. J. Stat. Softw. 57, 1–29 (2014).

Acknowledgements

We thank the many researchers that collected the field data that were used in this analysis. E.C.F. was supported by the National Socio-Environmental Synthesis Center (SESYNC) under funding received from the National Science Foundation DBI-1639145. J.C.S. considers this work a contribution to his VILLUM Investigator project “Biodiversity Dynamics in a Changing World” funded by VILLUM FONDEN (grant 16549).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

E.C.F. conceived the study with J.C.S., assembled and analysed data, and wrote the first draft. Both authors designed analyses and revised the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Peer review information Nature thanks Mauro Galetti, Thilo Gross and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data figures and tables

Extended Data Fig. 1 Biogeographic compartmentalization measured via meta-network modularity.

Modularity is calculated given species’ module membership based on the regions in which they are native. High modularity values indicate high compartmentalization along biogeographic regions, with distributions of bootstrapped values shown. Blue distribution shows modularity of the native-only meta-network. Red distribution shows modularity of the observed meta-network including introduced interactions. Red dashed line indicates distribution of modularity values for observed meta-networks sampled to have an equivalent number of interactions as in the native-only meta-network. Because this gives similar modularity values as in the observed meta-network, the higher modularity of the native-only meta-network is not explained by a lower number of interactions. Grey dashed line indicates distribution of modularity values for meta-networks simulated if species were homogenized randomly within biomes; this reflects a null expectation for biogeographic compartmentalization given a lack of dispersal barriers.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Beta diversity in species and interactions among local networks.

Relationship between pairwise distances and similarity of species in the community (1 – βS) and interactions (1 – βWN). Points represent 14,849 pairs of local networks and lines represent model fits from generalized additive models. Top row points in blue (a, b) are calculated using only native interactions and bottom row points in red (c, d) are calculated including introduced interactions.

Extended Data Fig. 3 Interaction breadth of species that have established as introduced species versus species that do not appear as introduced species.

For focal plant and animal species, the normalized degree—number of observed partners divided by the number of potential partners—was greater for species that appear as introduced than for species that do not. In a, b, introduced species are those that have been reported as introduced anywhere according to publicly available databases (χ2a = 59.7, d.f. = 1, Pa = 1.1 × 10−14, χ2p = 14.5, d.f. = 1, Pp = 1.4 × 10−4). In c, d, introduced species are those that are recorded in our database within a local network where they are introduced (χ2a = 235.3, d.f. = 1, Pa < 2.2 × 10−16, χ2p = 40.4, d.f. = 1, Pp = 2.1 × 10−10).

Extended Data Fig. 4 Introduced interactions reduce modularity of local networks.

Model estimates from mixed effects quantile regression, using random intercepts by study location. Points (jittered along x axis) show null model-corrected modularity calculated for 395 local networks as the difference between observed modularity and the average modularity of five corresponding networks generated under a null model. Coefficient estimates (±s.e.m.) at the 5th, 50th and 95th percentiles are, for the intercept, β0,5 = –0.050 (±0.005), β0,50 = 0.012 (±0.004), β0,95 = 0.130 (±0.019), and, for the effect of the proportion of introduced interactions, β1,5 = –0.009 (±0.020), β1,50 = –0.029 (±0.016), β1,95 = –0.079 (±0.037).

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Fricke, E.C., Svenning, JC. Accelerating homogenization of the global plant–frugivore meta-network. Nature 585, 74–78 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-020-2640-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-020-2640-y

This article is cited by

-

Alien plants and novel ecosystems in the Greater Tropics

Nature Reviews Biodiversity (2025)

-

Drivers and impacts of global seed disperser decline

Nature Reviews Biodiversity (2025)

-

Socioecological risks amplified by rising plant invasions in India

Nature Sustainability (2025)

-

On the structure of species-function participation in multilayer ecological networks

Nature Communications (2024)

-

Non-native ants are breaking down biogeographic boundaries and homogenizing community assemblages

Nature Communications (2024)