Abstract

In the mammalian lung, an apparently homogenous mesh of capillary vessels surrounds each alveolus, forming the vast respiratory surface across which oxygen transfers to the blood1. Here we use single-cell analysis to elucidate the cell types, development, renewal and evolution of the alveolar capillary endothelium. We show that alveolar capillaries are mosaics; similar to the epithelium that lines the alveolus, the alveolar endothelium is made up of two intermingled cell types, with complex ‘Swiss-cheese’-like morphologies and distinct functions. The first cell type, which we term the ‘aerocyte’, is specialized for gas exchange and the trafficking of leukocytes, and is unique to the lung. The other cell type, termed gCap (‘general’ capillary), is specialized to regulate vasomotor tone, and functions as a stem/progenitor cell in capillary homeostasis and repair. The two cell types develop from bipotent progenitors, mature gradually and are affected differently in disease and during ageing. This cell-type specialization is conserved between mouse and human lungs but is not found in alligator or turtle lungs, suggesting it arose during the evolution of the mammalian lung. The discovery of cell type specialization in alveolar capillaries transforms our understanding of the structure, function, regulation and maintenance of the air–blood barrier and gas exchange in health, disease and evolution.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$32.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 51 print issues and online access

$199.00 per year

only $3.90 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

The scRNA-seq datasets analysed are available at the GEO under the accession numbers GSE109774 (Tabula Muris13, https://tabula-muris.ds.czbiohub.org), GSE132042 (Tabula Muris Senis40, https://tabula-muris-senis.ds.czbiohub.org) and GSE119228 (a previous study34) or on Synapse under the accession number syn21041850 (Human Lung Cell Atlas16, https://hlca.ds.czbiohub.org). Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Hsia, C. C., Hyde, D. M. & Weibel, E. R. Lung structure and the intrinsic challenges of gas exchange. Compr. Physiol. 6, 827–895 (2016).

Malpighi, M. Dissertationes Epistolicæ de Pulmonibus. In Opera Omnia 320–332 (Pieter van der Aa, 1687) Available at https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/bibliography/566#.

Weibel, E. R. Morphological basis of alveolar-capillary gas exchange. Physiol. Rev. 53, 419–495 (1973).

Bertalanffy, F. D. & Leblond, C. P. Structure of respiratory tissue. Lancet 266, 1365–1368 (1955).

Barkauskas, C. E. et al. Type 2 alveolar cells are stem cells in adult lung. J. Clin. Invest. 123, 3025–3036 (2013).

Desai, T. J., Brownfield, D. G. & Krasnow, M. A. Alveolar progenitor and stem cells in lung development, renewal and cancer. Nature 507, 190–194 (2014).

Basil, M. C. et al. The cellular and physiological basis for lung repair and regeneration: past, present, and future. Cell Stem Cell 26, 482–502 (2020).

Liu, Q. et al. c-kit+ cells adopt vascular endothelial but not epithelial cell fates during lung maintenance and repair. Nat. Med. 21, 866–868 (2015).

Niethamer, T. K. et al. Defining the role of pulmonary endothelial cell heterogeneity in the response to acute lung injury. eLife 9, e53072 (2020).

Hamakawa, H. et al. Structure–function relations in an elastase-induced mouse model of emphysema. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 45, 517–524 (2011).

Golden, A. & Bronk, T. T. Diffuse interstitial fibrosis of lungs; a form of diffuse interstitial angiosis and reticulosis of the lungs. AMA Arch. Intern. Med. 92, 606–614 (1953).

Ackermann, M. et al. Pulmonary vascular endothelialitis, thrombosis, and angiogenesis in Covid-19. N. Engl. J. Med. 383, 120–128 (2020).

The Tabula Muris Consortium. Single-cell transcriptomics of 20 mouse organs creates a Tabula Muris. Nature 562, 367–372 (2018).

Lien, D. C. et al. Physiological neutrophil sequestration in the lung: visual evidence for localization in capillaries. J. Appl. Physiol. 62, 1236–1243 (1987).

Vila Ellis, L. et al. Epithelial Vegfa specifies a distinct endothelial population in the mouse lung. Dev. Cell 52, 617–630 (2020).

Travaglini, K. J. et al. A molecular cell atlas of the human lung from single-cell RNA sequencing. Nature (in the press).

Lambertz, M., Grommes, K., Kohlsdorf, T. & Perry, S. F. Lungs of the first amniotes: why simple if they can be complex? Biol. Lett. 11, 20140848 (2015).

Vaccaro, C. A. & Brody, J. S. Structural features of alveolar wall basement membrane in the adult rat lung. J. Cell Biol. 91, 427–437 (1981).

Bachofen, M. & Weibel, E. R. Structural alterations of lung parenchyma in the adult respiratory distress syndrome. Clin. Chest Med. 3, 35–56 (1982).

Szidon, J. P., Pietra, G. G. & Fishman, A. P. The alveolar-capillary membrane and pulmonary edema. N. Engl. J. Med. 286, 1200–1204 (1972).

Tian, X. et al. Subepicardial endothelial cells invade the embryonic ventricle wall to form coronary arteries. Cell Res. 23, 1075–1090 (2013).

Chen, H. I. et al. The sinus venosus contributes to coronary vasculature through VEGFC-stimulated angiogenesis. Development 141, 4500–4512 (2014).

Wang, Y. et al. Ephrin-B2 controls VEGF-induced angiogenesis and lymphangiogenesis. Nature 465, 483–486 (2010).

Chapman, H. A. et al. Integrin α6β4 identifies an adult distal lung epithelial population with regenerative potential in mice. J. Clin. Invest. 121, 2855–2862 (2011).

Madisen, L. et al. A robust and high-throughput Cre reporting and characterization system for the whole mouse brain. Nat. Neurosci. 13, 133–140 (2010).

Snippert, H. J. et al. Intestinal crypt homeostasis results from neutral competition between symmetrically dividing Lgr5 stem cells. Cell 143, 134–144 (2010).

Jackson, E. L. et al. Analysis of lung tumor initiation and progression using conditional expression of oncogenic K-ras. Genes Dev. 15, 3243–3248 (2001).

Pitulescu, M. E., Schmidt, I., Benedito, R. & Adams, R. H. Inducible gene targeting in the neonatal vasculature and analysis of retinal angiogenesis in mice. Nat. Protocols 5, 1518–1534 (2010).

Metzger, R. J., Klein, O. D., Martin, G. R. & Krasnow, M. A. The branching programme of mouse lung development. Nature 453, 745–750 (2008).

Shen, Z., Lu, Z., Chhatbar, P. Y., O’Herron, P. & Kara, P. An artery-specific fluorescent dye for studying neurovascular coupling. Nat. Methods 9, 273–276 (2012).

Susaki, E. A. et al. Advanced CUBIC protocols for whole-brain and whole-body clearing and imaging. Nat. Protocols 10, 1709–1727 (2015).

Bankhead, P. et al. QuPath: open source software for digital pathology image analysis. Sci. Rep. 7, 16878 (2017).

Butler, A., Hoffman, P., Smibert, P., Papalexi, E. & Satija, R. Integrating single-cell transcriptomic data across different conditions, technologies, and species. Nat. Biotechnol. 36, 411–420 (2018).

Cohen, M. et al. Lung single-cell signaling interaction map reveals basophil role in macrophage imprinting. Cell 175, 1031–1044 (2018).

Su, T. et al. Single-cell analysis of early progenitor cells that build coronary arteries. Nature 559, 356–362 (2018).

Qiu, X. et al. Reversed graph embedding resolves complex single-cell trajectories. Nat. Methods 14, 979–982 (2017).

Chen, M. B et al. Brain endothelial cells are exquisite sensors of age-related circulatory cues. Cell Rep. 30, 4418–4432 (2020).

Ghandour, M. S., Langley, O. K., Zhu, X. L., Waheed, A. & Sly, W. S. Carbonic anhydrase IV on brain capillary endothelial cells: a marker associated with the blood-brain barrier. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 89, 6823–6827 (1992).

Sender, S. et al. Localization of carbonic anhydrase IV in rat and human heart muscle. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 46, 855–861 (1998).

The Tabula Muris Consortium. A single-cell transcriptomic atlas characterizes ageing tissues in the mouse. Nature 583, 590–595 (2020).

Fleming, R. E., Crouch, E. C., Ruzicka, C. A. & Sly, W. S. Pulmonary carbonic anhydrase IV: developmental regulation and cell-specific expression in the capillary endothelium. Am. J. Physiol. 265, L627–L635 (1993).

Beigneux, A. P. et al. Glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored high-density lipoprotein-binding protein 1 plays a critical role in the lipolytic processing of chylomicrons. Cell Metab. 5, 279–291 (2007).

Davies, B. S. et al. GPIHBP1 is responsible for the entry of lipoprotein lipase into capillaries. Cell Metab. 12, 42–52 (2010).

Esnouf, M. P. Biochemistry of blood coagulation. Br. Med. Bull. 33, 213–218 (1977).

Davie, E. W., Fujikawa, K. & Kisiel, W. The coagulation cascade: initiation, maintenance, and regulation. Biochemistry 30, 10363–10370 (1991).

Nikolić, M. Z., Sun, D. & Rawlins, E. L. Human lung development: recent progress and new challenges. Development 145, dev163485 (2018).

Goldenberg, N. M. & Kuebler, W. M. Endothelial cell regulation of pulmonary vascular tone, inflammation, and coagulation. Compr. Physiol. 5, 531–559 (2015).

Kreisel, D. et al. Cutting edge: MHC class II expression by pulmonary nonhematopoietic cells plays a critical role in controlling local inflammatory responses. J. Immunol. 185, 3809–3813 (2010).

Milani, A. Beiträge zur Kenntnis der Reptilienlunge. II. Zool. Jahrb. Abt. Anat. Ontogenie Tiere 10, 93–156 https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/item/41831#page/103/mode/1up (1897).

Sanders, R. K. & Farmer, C. G. The pulmonary anatomy of Alligator mississippiensis and its similarity to the avian respiratory system. Anat. Rec. 295, 699–714 (2012).

Maina, J. N. & West, J. B. Thin and strong! The bioengineering dilemma in the structural and functional design of the blood-gas barrier. Physiol. Rev. 85, 811–844 (2005).

Acknowledgements

We thank S. Quake and the Chan Zuckerberg Biohub for our collaborative scRNA-seq studies of the mouse and human lung; R. Adams, H. Chapman and K. Red-Horse for sharing mouse lines; P. Bogard, Y. Ouadah and S. Jang for advice and discussion; O. Cleaver for an antibody recommendation; D. Cornfield and the Stanford Center for Excellence in Pulmonary Biology for providing resources and space, the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology for access to fetal lung tissue; R. Elsey and the Rockefeller Wildlife Refuge for providing the alligators; F. H. Espinoza for sharing the expression pattern of Aplnr in the developing plexus; J. Perrino and I. Phanwar of the Cell Sciences Imaging Facility for advice, sample preparation and assistance with electron microscopy analysis; L. Taylor, the Department of Comparative Medicine Animal Histology Services, the Department of Pathology Immunohistochemistry laboratory and the Human Pathology/Histology Service Center for technical assistance; M. Kumar, E. Spiekerkoetter and Y. Ouadah for critical reading of the manuscript; and E. Weibel (1929–2019) for his careful observations of the cellular structure of the alveolus. Silhouettes in Extended Data Fig. 11 are from PhyloPic (http://phylopic.org/). This work was supported by the Vera Moulton Wall Center for Pulmonary Vascular Disease at Stanford and by grants from the Austrian Science Fund (J-3373) and the American Heart Association (16POST27250261) to A.G.; the National Science Foundation (IOS 1055080) to C.G.F.; and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (K99 HL135258) to M.G. K.J.T. was supported by a Paul and Mildred Berg Stanford Graduate Fellowship. B.Z. was supported by the Strategic Priority Research Program of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (XDB19000000, XDA16010507). M.A.K. is an investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. Funding for the instrumentation used in the electron microscopy experiments was provided by an ARRA Award (1S10RR026780-01) from the National Center for Research Resources.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.G., M.A.K. and R.J.M. conceived and designed the project, analysed the data and wrote the manuscript. A.G. and R.J.M. performed experiments, assisted by F.Z. A.G. and R.J.M. performed the computational analyses of scRNA-seq data. C.G.F. contributed to the design and interpretation of the evolutionary analysis, collected alligator and turtle lung tissue and contributed to the manuscript. K.J.T. made initial observations about endothelial proliferation and elastin fibre remodelling after elastase injury and contributed to the design and execution of the elastase injury experiments. S.Y.T. provided tissue from a patient with adenocarcinoma and pathological analysis. M.G. provided fetal human lung tissue. B.Z. provided tissue and a mouse line. J.A.F. provided expertise and infrastructure, and supported the work. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Peer review information Nature thanks Shalez Itzkovitz and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data figures and tables

Extended Data Fig. 1 Molecular characterization and mapping of the two alveolar capillary cell types.

a, Feature plots showing log-transformed expression of marker genes used to annotate five molecularly distinct clusters (see t-SNE plot in Fig. 1b) derived by unsupervised clustering of lung endothelial cells in the Tabula Muris scRNA-seq Smart-seq2 data13 for adult mouse lung. We identified two endothelial cell clusters as capillaries based on expression of carbonic anhydrases (Car4, Car14) that catalyse the conversion of bicarbonate to carbon dioxide41, Gpihbp1, a lipoprotein-binding protein that localizes to the luminal membrane of alveolar capillaries42, and lipoprotein lipase (Lpl), which is transported to the capillary lumen by Gpihbp143. b, Heat map showing log-transformed expression of selected cluster markers in individual pulmonary artery, vein, lymphatics and alveolar capillary (aCap, gCap) endothelial cells identified in the Tabula Muris Smart-Seq2 data13. c, Co-expression of alveolar capillary cell type markers Apln (aCap) and Aplnr (gCap) in a single alveolar capillary intermediate (IM) endothelial cell (arrow; marked by Cldn5) in adult mouse lung, as detected by smFISH. d, Co-expression of aCap markers (Apln and Ednrb) in a subset (aCap cells) of alveolar endothelial cells (marked by Cldn5) in adult mouse lung. e, Co-expression of aCap markers Ednrb and Car4 but not Aplnr, a gCap marker, in a subset (aCap cells) of adult mouse lung alveolar endothelial cells. e’, Boxed region from e at higher magnification. Filled arrowhead indicates aCap cell expressing high levels of Car4. Open arrowhead points to gCap cell expressing low levels of Car4. f, g, Co-expression of gCap markers Gpihbp1 (f) or H2-Ab1 (g), a major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II gene, and Aplnr in a subset (gCap cells) of adult mouse lung alveolar endothelial cells. h, i, Quantification of the relative abundance (in % of capillary endothelial cells) of the two alveolar capillary populations (aCap, gCap) and rare cells (IM) that co-express aCap and gCap markers at the pleura and in intra-acinar regions (h), or in different lobes (i, left versus right cranial) in lungs from 3-month old mice. Data shown as mean ± s.d.; n = 500 cells scored per mouse; n = 3 mice; P values comparing cell type abundance by two-sided Wilcoxon rank sum test: aCap (h, 0.2; i, 0.2), gCap (h, 0.4; i, 0.2), IM (h, 0.7; i, 0.8). n.s., not significant. j, aCap (marked by Ednrb) and gCap (marked by Ptprb) cells in lungs from 3- and 24-month old mice. Endothelial cells are marked by Cldn5. k, l, Co-expression of tdTomato lineage label (asterisks) and either aCap marker Ednrb but not gCap marker Aplnr in an Apln-creER; Rosa26-tdTomato lung (k) or gCap marker Aplnr but not aCap marker Apln in an Aplnr-creER; Rosa26-tdTomato lung (l) harvested one month after mature aCap (k) or gCap (l) cells were lineage-labelled. Lineage-labelled cells (asterisks) continue to express the marker (Ednrb, aCap; Aplnr, gCap) of the labelled population. m, n, Quantification of percent of lineage-labelled cells in Apln-creER; Rosa26-tdTomato (m) or Aplnr-creER; Rosa26-tdTomato (n) lungs that continue to express the aCap marker, gCap marker, or markers of both cell types (IM) after 48 h, 1, 6, or 14 months (500–2,000 cells scored at each time point from multiple regions in each of two separate lobes from one lung). Blue (c–g, j–l), DAPI. Scale bars, 10 μm.

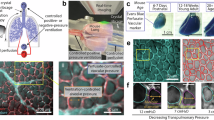

Extended Data Fig. 2 Alveolar capillary cell morphologies.

a–d, Additional examples of single cytoplasmic YFP- or RFP-expressing plexus cells at E12.5 (a), aerocytes at E18.5 (b), gCap cells at P0 (c) and aerocytes at P0 (d). Plexus and gCap cells were labelled in Aplnr-creER; Rosa26-Confetti lungs; aerocytes were labelled in Apln-creER; Rosa26-Confetti lungs. Pores, present in some aerocytes by E18.5, but not plexus or P0 gCap cells, are marked by dots. e, f, Additional examples of single gCap cells (e) or aerocytes (f) expressing cytoplasmic RFP or YFP in adult Aplnr-creER; Rosa26-Confetti (e) or Apln-creER; Rosa26-Confetti (f) lungs. Dotted circles outline two alveoli spanned by a single aerocyte (f). Note that gCap cells are less morphologically diverse than aerocytes. g, h, Quantification of individual plexus, aerocyte (aCap), or gCap cell surface area (g) and pore number (h) at indicated times. n > 10 cells scored for each cell type at each time point from n = 2 lungs; see Methods for exact cell number. Blue, elastin fibres highlighting the alveolar entrance. Grey bar, mean value. Scale bars, 10 μm.

Extended Data Fig. 3 Capillary cells in the lung and other organs.

a, Bronchial (systemic) capillary cell immunostained for tdTomato (red) in adult Aplnr-creER; Rosa26-tdTomato lung. Airway epithelium is immunostained for E-cadherin (blue). b–f, Single capillary cells labelled with membrane targeted CFP (b) or cytoplasmic YFP (c–f) in brain (b), heart (c), small intestine (d), kidney glomerulus (e) or thyroid (f), in which capillaries are arranged in baskets similar to pulmonary alveoli, from an adult Cdh5-creER; Rosa26-Confetti mouse. Capillaries labelled with tomato lectin (blue, b–f). e’, Cell in boxed region in e at higher magnification, along with other examples of labelled glomerular endothelial cells. g, Single endothelial tip cell expressing cytoplasmic YFP in developing (P7) Apln-creER; Rosa26-Confetti mouse retina. Filled arrowheads, filopodia. h, i, Scatter plots of alveolar aCap and gCap signature scores assigned to annotated lung, heart and brain capillary endothelial cells identified in the Tabula Muris scRNA-seq Smart-seq2 data13 (h) or annotated lung, kidney glomerular and mammary gland capillary endothelial cells identified in the Tabula Muris Senis scRNA-seq droplet data for 1-, 3-, 18-, 21- and 30-month-old mice40 (i). Lung capillary cells segregate into two clusters, with annotated gCap cells having high gCap and low aCap signature scores, and annotated aCap cells having low gCap and high aCap signature scores. Heart (h), brain (h), glomerular (i) and mammary gland (i) capillary cells have high gCap and low aCap signature scores and each form a single cluster near gCap but not aCap cells, suggesting that they are more similar to gCap cells and any heterogeneity within these other capillary cell populations is different from that in the lung. j–l, Some aCap and gCap markers (aCap, Ednrb (j, k); gCap, Ptprb (j) or Gpihbp1 (k)) are broadly co-expressed in glomerular endothelial cells (Pecam1) in adult mouse kidney whereas expression of others (aCap, Apln, or gCap, Aplnr; l) is detected only in small numbers of cells or not at all. Dotted lines outline glomeruli. j’, k’, l’, Boxed regions from j–l at higher magnification. Arrows (j’, k’) point to cells co-expressing the markers. Blue (j–l), DAPI. Scale bars, 10 μm.

Extended Data Fig. 4 Functional compartmentalization of the alveolus.

a, Transmission electron micrographs of alveolar walls from adult mouse lungs, pseudocoloured to highlight cells and connective tissue (extracellular matrix (ECM) or fibres). Apln-creER; Rosa26-tdTomato (to label aerocytes) or Aplnr-creER; Rosa26-tdTomato (to label gCap cells) lungs were immunostained for tdTomato (detected with DAB and NiCl2, heavy black stain). Labelled aerocytes but not gCap cells are associated with thin regions of the air–blood barrier (delimited by dashed lines), where the epithelium is tightly apposed to the endothelium. Some thin regions do not contain labelled aerocytes as aerocyte labelling using Apelin-creER is inefficient. Thick regions, where the epithelium is separated from the endothelium by fibres or other cells, can be associated with either aerocytes or gCap cells. AT1 cell, alveolar type 1 epithelial cell; AT2 cell, alveolar type 2 epithelial cell. Micrographs in top left, middle and bottom panels are shown without pseudocolouring in Fig. 2g–i. b, c, gCap cells associate with fibroblasts. Alveoli with labelled aerocytes (aCap) in Apln-creER; Rosa26-tdTomato (b) or gCap cells in Aplnr-creER; Rosa26-tdTomato (c) lungs immunostained for integrin α8 to show alveolar fibroblasts16. Asterisks mark aerocytes that do not associate with fibroblasts (in b) and gCap cells that do (in c). Example regions of alveoli not covered by fibroblasts are dotted. Note that the dotted region in b is occupied by an aerocyte not overlaid by fibroblasts, whereas fibroblasts overlay gCap cells in c. d, Selected genes with known functions, which are differentially expressed between the two alveolar capillary cell types in adult mouse lung13. Pro, procoagulants; anti, anticoagulants44,45. e, Summary of signalling interactions between capillary cell types and surrounding cells in the mouse alveolus. Arrows indicate direction of signalling. f, Schematic representation of an alveolus highlighting proposed specialized functions and signalling interactions of alveolar capillary cell types. AT1, alveolar type 1 epithelial cell; AT2, alveolar type 2 epithelial cell. Scale bars, 2 μm (a); 10 μm (b, c).

Extended Data Fig. 5 Proliferation of gCap cells after elastase-induced injury.

a, Elastin fibres (black), labelled with fluorescent hydrazide, in lungs of wild-type mice treated with elastase or mock-treated with saline as control. Loss of elastin fibres in injured areas (dashed outlines) is apparent one day after intratracheal instillation of elastase. At one month after injury, regions containing abnormally thickened elastin fibres and enlarged airspaces are evident. Boxed areas are shown at higher magnification. b, Scheme for detecting proliferation of alveolar capillary cells after elastase injury. aCap and gCap cells were lineage-labelled in adult Apln-creER; Rosa26-tdTomato (for aCap cells) or Aplnr-creER; Rosa26-tdTomato (for gCap cells) mice three weeks before elastase administration, then EdU was administered in drinking water and capillary cells were analysed at the indicated times after injury. c–f, Proliferation analysed by cumulative EdU incorporation in lineage-labelled (red) aCap cells (top panels in c–f) and gCap cells (bottom panels in c–f) at 3 days (c, d), 1 week (e) or 6 weeks (f) after instillation of saline (as control; c) or elastase (d–f). Boxed areas are shown at higher magnification, with cell bodies of individual capillary cells outlined. After treatment with elastase, gCap cells proliferated in injured areas. White, elastin fibres. Scale bars (c–f), 10 μm.

Extended Data Fig. 6 Development, maturation and ageing of specialized alveolar capillary cell types.

a, Expression of Aplnr throughout plexus (labelled by Pecam1) surrounding a developing airway at E12.5, detected by smFISH. b, Expression of mature aerocyte markers Apln and Ednrb in plexus (labelled by Pecam1) surrounding a developing airway at E12.5. Plexus cells expressing Apln but not Ednrb are marked by asterisks. Ednrb is expressed at high levels in Pecam1-negative (stromal) cells, but rarely and only at low levels in Pecam1-positive endothelial cells (arrow) at this stage. c, The subpopulation of Apln-expressing cells within the Aplnr+ plexus gives rise to both capillary cell types, as shown by expression of tdTomato transcripts in both aerocyte (filled arrowheads, marked by Ednrb) and gCap (open arrowheads, marked by Aplnr) cells of P21 Apln-creER; Rosa26-tdTomato lung lineage-labelled at E12.5, demonstrating that even plexus cells that express an aerocyte marker are uncommitted. c’, Lineage-labelled aerocyte (filled arrowhead) and gCap (open arrowheads) cells shown at higher magnification. d, Alveolar capillary clone in a P25 Aplnr-creER; Rosa26-Confetti lung composed of both aCap and gCap cells (higher magnification at right) derived from a single YFP-expressing plexus cell labelled at E14.5. e, Composition of Aplnr-creER; Rosa26-Confetti clones induced at E14.5 and analysed at P25, ordered by clone size. All analysed clones, with the exception of clone number 1, contained both aCap and gCap cells. Some clones also contained cells located in larger vessels (LV). Both coherent clones (in which all cells are touching) and dispersed clones were observed, suggesting that there can be cell movement during capillary development. The number of cells of each type was scored from 3D renderings of confocal z-stacks, as described in the Methods. Clone 4 is shown in Fig. 4e; clone 28 is shown in Extended Data Fig. 6d and Supplementary Video 4. RCr, right cranial lobe; RAc, right accessory lobe; RCd, right caudal lobe; L, left lobe. f, The Aplnr+ population remains uncommitted even after birth. The population labelled at P7 in an Aplnr-creER; Rosa26-tdTomato lung gives rise to both aCap and gCap cells, as shown by co-expression of tdTomato lineage label and either aCap marker Apln or gCap marker Aplnr at P21, detected by smFISH. f’, f’’, Lineage-labelled aerocyte and gCap cells shown at higher magnification. g, Expression of aerocyte markers Car4, Ednrb and Apln in developing mouse lung at indicated stages. Aerocytes (asterisks), identified by marker co-expression, begin to emerge at E17.5. Insets, cells in boxed regions at higher magnification. h, Plexus and capillary cells identified in scRNA-seq data for developing mouse lung34 arranged as tree-shaped branched developmental trajectory inferred using Monocle236. Cells collected at the indicated stages are coloured to show plexus located along the stem before the branchpoint, maturing and mature aerocytes along the bottom branch, and maturing and mature gCap cells along the top branch. Note that cells from a single late embryonic or early postnatal time point are found at multiple positions along the trajectory. This analysis is consistent with that presented in a previous study15. Each cell type undergoes distinct and asynchronous molecular and morphological maturation (see Extended Data Fig. 2), suggesting that the two capillary cell specialization programs are under separate genetic control. i, Heat map showing log-transformed expression levels in individual plexus and capillary cells for selected genes differentially expressed during aerocyte emergence and maturation. Many aerocyte markers are expressed in emerging aerocytes; others are only expressed in mature aerocytes. j, Developmental trajectory plot (top) and feature plots showing log-transformed expression for selected gCap markers expressed only in mature gCap cells (upper branch tip). k, l, Expression of Vwf in the gas-exchange region at 3 (k) and 24 months (l), as detected by smFISH. k’, l’, Boxed regions from k and l shown at higher magnification. Endothelial cells are marked by Cldn5 expression. At 24 months, Vwf is induced in gCap cells (marked by Ptprb, open arrowheads), but not aerocytes (filled arrowhead). m, Schematic representation of Vwf induction in gCap cells with ageing. At 24 months, Vwf is more broadly expressed in alveolar capillaries than at 3 months but only in gCap cells (marked by Ptprb). Blue, DAPI (a–c, f, g, k’, l’). Scale bars, 10 μm.

Extended Data Fig. 7 Emergence and maturation of the alveolar capillary cell types in developing mouse lung.

a, t-SNE plots with plexus and capillary endothelial cells from embryonic, postnatal and adult stages (n = 3,094 cells) identified in scRNA-seq MARS-Seq data for developing mouse lung34. Cells from each indicated stage are coloured black, except emerging/maturing aerocytes (aCap), first evident at E18.5 in this dataset, light blue; mature aerocytes, dark blue; mature gCap cells, dark green. See also feature plots in Supplementary Data 3. b, Branched heat map showing gene expression changes during the transformation of plexus into mature alveolar capillary cell types. Normalized expression values (z-scores) are plotted for genes with branch-dependent expression, identified by branched expression analysis modelling (BEAM) (n = 1119 genes at q-value < 0.05), and genes that vary as a function of pseudotime, identified by differential expression analysis as implemented in Monocle2 (n = 3,734 genes at q-value < 0.05), in plexus and capillary cells. Cells are ordered by ascending pseudotime values with plexus in the middle, mature aerocytes (aCap) on the left and mature gCap cells on the right. Genes (n = 4,129) are grouped by expression pattern and selected genes are indicated on the heat map. Branchpoint genes change their expression where the stem splits into aCap and gCap branches. Capillary genes are expressed in both aCap and gCap cells, but not plexus. An uncropped version of the heat map is shown in Supplementary Data 4. c, Developmental trajectory plot (top) and feature plots (below) showing log-transformed expression for selected genes in plexus (cells located along the stem before the branchpoint), aerocytes (bottom branch) and gCap cells (top branch).

Extended Data Fig. 8 Specialized alveolar capillary cell types in the human lung.

a, Alveolar capillary network in adult human lung immunostained for PECAM1 and VE-cadherin. Boxed region shown at higher magnification. b, t-SNE plot of annotated artery, vein, lymphatics, bronchial endothelial, aerocyte (aCap) and gCap cell clusters identified in scRNA-seq droplet data for adult human lung16 (75-year-old man). c, Heat map showing log-transformed expression of selected cluster markers in individual endothelial cells. L., lymphatics. d–g, Expression of aerocyte (EDNRB, d, or APLN, f) and gCap (EDN1, e, g or VWF, g) markers in alveolar endothelial cells (marked by CLDN5, d–f), detected by smFISH in adult human lung. d’–g’, d’’-g’’, Aerocytes and gCap cells shown at higher magnification. h, As in the mouse lung (see Extended Data Fig. 1c), occasional human alveolar capillary cells co-express aerocyte (APLN) and gCap (EDN1) markers. h’, Boxed region shown at higher magnification with clustered capillary intermediate cells (arrows) near a large vessel (dotted line in h) and a nearby single cell. i, Quantification of the relative abundance (in % of capillary endothelial cells) of the two alveolar capillary populations (aCap, gCap) and intermediate (IM) cells that co-express aCap and gCap markers in adult human lung (n = 2 individuals; 69- and 75-year-old men; 500–600 capillary cells scored per lung; data as mean). j, j’ Co-expression of aerocyte markers EDNRB, APLN and CA4 in emerging aerocytes (dotted outlines) but not plexus cells (asterisks) in fetal human lung (23 weeks gestational age, corresponding to E16.5–17.5 in mouse46). At 23 weeks, 6% of CA4-expressing cells also express APLN and EDNRB at high levels (emerging aerocytes; 5 or more puncta per cell), compared to 0% at 17 weeks (500 CA4+ cells scored at each time point from one lung). Inset, adjacent haematoxylin and eosin (H&E)-stained section. j’, Boxed region from j at higher magnification. Blue (a, d–h, j), DAPI. Scale bars, 10 μm.

Extended Data Fig. 9 Altered capillary cell patterns in mouse and human lung tumours.

a, Human lung adenocarcinoma with tumour vessels immunostained for CD34 (brown), an endothelial marker that is expressed by both aCap and gCap cells16. Blue, haematoxylin counterstain. a’, Co-expression of alveolar capillary cell type markers EDNRB (aCap) and PTPRB (gCap) in vessels surrounding tumour acinus (boxed in a), as detected in adjacent section by smFISH. a’’, Boxed region from a’ showing two endothelial cells (marked by CLDN5) co-expressing aerocyte and gCap markers (dotted outlines) at higher magnification. Merged image also shown in Fig. 4l. b–c’, Co-expression (asterisks) of alveolar capillary cell type markers (Ednrb, b, b’ or Apln, c, c’ (aCap) and Ptprb, b, b’ or Aplnr, c, c’ (gCap)) in a subset of endothelial cells (marked by Cldn5, b’) of mouse lung adenomas induced by conditional expression of an activating Kras mutation in AT2 cells6. Open arrowheads point to gCap cells. b’, c’, Boxed regions in b and c shown at higher magnification. d, Quantification of the relative abundance (in % of capillary endothelial cells) of the two alveolar capillary populations (aCap, gCap) and intermediate cells (IM) that co-express aCap and gCap markers in adenomas (n = 1,332 cells scored in 21 tumour sections from n = 2 mice) and alveoli (n = 11,219 cells scored in n = 5 mice at 3 months). e, Scatter plot of gCap:IM ratios in individual adenomas (n = 21). Grey bar, mean value. The fraction of intermediate cells varies from tumour to tumour even within the same lung, perhaps reflecting different stages of tumour development. f, f’, Expression of MHC class II gene H2-Ab1 (normally expressed in gCap cells; see Extended Data Fig. 1g) is lost in gCap cells (open arrowhead) in mouse adenomas, suggesting that they may lose their antigen presentation function. H2-Ab1 is also not expressed by the abundant tumour capillary cells that co-express Aplnr and Ednrb (asterisk). f’, Boxed region in f shown at higher magnification. Scale bars, 200 μm (a); 10 μm (a’–c’, f, f’).

Extended Data Fig. 10 Conserved and species-specific specialization of alveolar capillary cells.

a, Dot plots showing log-transformed average expression levels and percent expression in aerocytes (aCap) and gCap cells for selected genes with known physiological and immune functions, ligands and receptors or co-receptors and transcription factors, which are differentially expressed by the two capillary cell types in adult mouse lung (Tabula Muris scRNA-seq Smart-Seq2 data13) or human lung (Human Lung Cell Atlas16; droplet (10X) or Smart-Seq2 data; 75-year-old man). b, Selected differentially expressed genes in the human lung with known functions. c–e, Diagrams of selected proposed specialized alveolar capillary functions. Selected genes involved in leukocyte trafficking and vasomotor control47 (see legend to Fig. 3d) show the same specialized expression pattern in mouse and human (c; type 0), whereas some genes involved in haemostasis show specialized expression only in the human lung (d; type 1), and some antigen-presenting genes48 show specialized expression that switches cell type between mouse and human (e; type 2). Blue, genes expressed in aerocytes; green, genes expressed in gCap cells; yellow, genes expressed in both aerocytes and gCap cells; purple, genes expressed in pericytes16.

Extended Data Fig. 11 Faveolar capillary cell types in alligator and turtle.

a, Cladogram illustrating the phylogenetic relationships between amniote taxa with different lung structures. The relationship between testudines and other diapsids is unresolved (dotted line). Ma, million years. b, h, Internal anatomy of alligator (A. mississippiensis; b) and turtle (Emys orbicularis; h) lungs, reproduced from a classical study49. Alligator and turtle lungs have multiple separate airspaces (‘chambers’), smooth muscle, a branched vasculature and terminal airspaces known as faveoli, in which gas exchange occurs across a thick air–blood barrier50,51. c, i, Gas-exchange regions of American alligator (A. mississippiensis; c) and western painted turtle (C. p. bellii, i) lungs, stained with haematoxylin and eosin. d, Faveolar capillary network in American alligator lung immunostained for CLDN5 (red; endothelium). Green, elastin fibres. e, Co-expression (asterisks) of alveolar capillary cell type markers CA4 (aCap) and PTPRB (gCap) in faveolar endothelial cells (marked by CLDN5) in juvenile American alligator lung as detected by smFISH. e’, Faveolar capillary cell in boxed region from e shown at higher magnification. Note that faveolar capillary cells—reminiscent of the intermediate cells found in adult mouse and human lungs—appear to differ in gene expression from the developmental precursors identified in the mouse vascular plexus, in which aCap and gCap markers are only rarely co-expressed (Supplementary Data 2). f, Co-expression (asterisks) of alveolar capillary cell-type markers EDNRB (aCap) and PTPRB (gCap) in faveolar endothelial cells (marked by CLDN5) in adult American alligator lung. f’, Faveolar capillary cell in boxed region from f shown at higher magnification. g, Alligator faveolar septum immunostained for CLDN5 (red; endothelium) and E-cadherin (white; epithelium). Dotted line, capillary lumen. j, k, Faveolar capillary network in western painted turtle lung immunostained for CLDN5 (red) to label endothelial cells. Neighbouring faveoli are separated by septa with a capillary layer on each side of the septal wall (j). A capillary lumen is outlined (j, dotted line). l, Co-expression (asterisks) of alveolar capillary cell type markers (EDNRB, aCap and APLNR, gCap) in faveolar endothelial cells (marked by CLDN5) in adult turtle lung. l’, Two faveolar capillary cells in boxed region from l shown at higher magnification. m, Faveolar septum in turtle lung immunostained for CLDN5 (red) to label endothelial cells in the capillary layer on each side of the septal wall and E-cadherin (white) to label respiratory epithelium. A capillary lumen is outlined (dotted line). Blue, DAPI. Scale bars, 200 μm (c, i), 10 μm (d–g, j–m).

Supplementary information

Supplementary Data

Supplementary Data 1. Lineage tracing of the vascular plexus in the embryonic lung. Plexus cells in Aplnr-creER; Rosa26-tdTomato embryos were labeled at E12.5; at P60 alveolar capillaries express the lineage label, as shown by immunostaining for endomucin, to visualize endothelial cells, and tdTomato. Boxed region shows alveolus displayed at higher magnification in Fig. 4c.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary Data 2. Heatmap showing log-transformed expression levels in individual plexus and capillary endothelial cells for selected genes. Cells were identified in scRNAseq data for developing mouse lung (ref. 34). Plexus-enriched genes include cell cycle genes largely not expressed in the mature alveolar capillary cell types whereas the salt-and-pepper patterns of adult capillary cell type markers in the plexus suggest noisy expression of mature markers in plexus cells.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary Data 3. Feature plots showing log-transformed gene expression levels in individual plexus and capillary endothelial cells for selected plexus, capillary, and pan-endothelial genes. Cells were clustered and identified in scRNAseq data for developing mouse lung (ref. 34). See also tSNE plots in Extended Data Fig. 7a.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary Data 4. Branched heatmap showing gene expression changes during the transformation of plexus into mature alveolar capillary cell types. Genes were clustered hierarchically to visualize groups of genes that co-vary across pseudotime. Cells are ordered by ascending pseudotime values (plexus, middle; mature aerocytes, left; mature gCap cells, right). See also Extended Data Fig. 7b.

Supplementary Table

Supplementary Table 1. Markers that distinguish mouse endothelial cell types. Rows show genes and columns show p-values, average expression fold changes, and the percentage of cells expressing a gene. Two-sided Wilcoxon rank sum test with Bonferroni correction (adjusted p-value < 0.01), Tabula Muris Smart-Seq2 dataset.

Supplementary Table

Supplementary Table 2. Markers that distinguish mouse aerocytes from gCap cells. Rows show genes and columns show p-values, average expression fold changes, and the percentage of cells expressing a gene. Two-sided Wilcoxon rank sum test with Bonferroni correction (adjusted p-value < 0.01), Tabula Muris Smart-Seq2 dataset.

Supplementary Table

Supplementary Table 3. Markers that distinguish human aerocytes from gCap cells. Rows show genes and columns show p-values, average expression fold changes, and the percentage of cells expressing a gene. Two-sided Wilcoxon rank sum test with Bonferroni correction (adjusted p-value < 0.01), Human Lung Cell Atlas Smart-Seq2 dataset, patient 1.

Video 1. Aerocyte morphology

Single aerocyte expressing cytoplasmic RFP in an adult Apln-creER; Rosa26-Confetti mouse lung. Blue, elastin fibers.

Video 2. gCap cell morphology

Single gCap cell expressing cytoplasmic YFP in an adult Aplnr-creER; Rosa26-Confetti mouse lung. Blue, elastin fibers.

Video 3. Aerocytes and gCap cells form multicellular tubes

Aerocyte (red) and gCap (yellow) cell forming multicellular tubes within the capillary network of a single alveolus in an adult Cdh5-creER; Rosa26-Confetti mouse lung. Blue, elastin fibers.

Video 4. Plexus cells are bipotent progenitors that give rise to both aerocytes and gCap cells

Clone in a P25 Aplnr-creER; Rosa26-Confetti lung composed of aerocytes and gCap cells derived from a single YFP-expressing plexus cell labeled at E14.5.

Video 5. Alveolar capillaries in the human lung

Alveolar capillary network in an adult human lung immunostained for VE-Cadherin (white). Blue, DAPI.

Video 6. Faveolar capillaries in the American alligator lung

Faveolar capillary network in an American alligator lung immunostained for Claudin 5 (red) to label endothelial cells. Neighboring faveoli are separated by septa supported by trabeculae containing elastin fibers (green).

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Gillich, A., Zhang, F., Farmer, C.G. et al. Capillary cell-type specialization in the alveolus. Nature 586, 785–789 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-020-2822-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-020-2822-7

This article is cited by

-

Anti-CD31 antibody preconditioning for enhancement of endothelial cell capture and vascularization: a novel strategy for bioengineering lung scaffolds

Journal of Biological Engineering (2026)

-

Circulating Endothelial Compartment and Progenitor Cell Dynamics in Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis: Findings from the COFI Trial

Stem Cell Reviews and Reports (2026)

-

Aberrant cellular communities underlying disease heterogeneity in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

Nature Genetics (2026)

-

Unveiling the immunomodulatory dance: endothelial cells’ function and their role in non-small cell lung cancer

Molecular Cancer (2025)

-

Dissecting endothelial cell heterogeneity with new tools

Cell Regeneration (2025)