Abstract

COVID-19 accelerated a decade-long shift to remote work by normalizing working from home on a large scale. Indeed, 75% of US employees in a 2021 survey reported a personal preference for working remotely at least one day per week1, and studies estimate that 20% of US workdays will take place at home after the pandemic ends2. Here we examine how this shift away from in-person interaction affects innovation, which relies on collaborative idea generation as the foundation of commercial and scientific progress3. In a laboratory study and a field experiment across five countries (in Europe, the Middle East and South Asia), we show that videoconferencing inhibits the production of creative ideas. By contrast, when it comes to selecting which idea to pursue, we find no evidence that videoconferencing groups are less effective (and preliminary evidence that they may be more effective) than in-person groups. Departing from previous theories that focus on how oral and written technologies limit the synchronicity and extent of information exchanged4,5,6, we find that our effects are driven by differences in the physical nature of videoconferencing and in-person interactions. Specifically, using eye-gaze and recall measures, as well as latent semantic analysis, we demonstrate that videoconferencing hampers idea generation because it focuses communicators on a screen, which prompts a narrower cognitive focus. Our results suggest that virtual interaction comes with a cognitive cost for creative idea generation.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$32.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 51 print issues and online access

$199.00 per year

only $3.90 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

The data (raw and cleaned) collected by the research team and reported in this Article and its Supplementary Information are available on Research Box (https://researchbox.org/282), except for the video, audio recordings and transcripts of participants, because we do not have permission to share the participants’ voices, faces or conversations. The cleaned summary data for the field studies are available in the same Research Box, but the raw data must be kept confidential, as these data are the intellectual property of the company. The Linguistic Analysis database is available online (https://liwc.wpengine.com/). Extended Data Tables 1–5 and Extended Data Figs. 2 and 3 are summary tables and figures, and the raw data associated with these tables are on Research Box (https://researchbox.org/282). Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

All custom code used to clean and analyse the data is available at Research Box (https://researchbox.org/568). The Linguistic Analysis database is available online (https://liwc.wpengine.com/). OpenFace is available at GitHub (https://github.com/TadasBaltrusaitis/OpenFace).

Change history

07 June 2022

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-022-04852-5

References

Barrero, J. M., Bloom, N. & Davis, S. J. Don’t force people to come back to the office full time. Harvard Business Review (24 August 2021).

Barrero, J. M., Bloom, N. & Davis, S. Why Working from Home Will Stick. NBER Working paper (2021); http://www.nber.org/papers/w28731.pdf.

Wuchty, S., Jones, B. F. & Uzzi, B. The increasing dominance of teams in production of knowledge. Science 316, 1036–1039 (2007).

Daft, R. L. & Lengel, R. H. Organizational information requirements, media richness and structural design. Manage. Sci. 32, 554–571 (1986).

Short, J., Williams, E. & Christie, B. The Social Psychology of Telecommunications (John Wiley & Sons, 1976).

Dennis, A. R., Fuller, R. M. & Valacich, J. S. Media, tasks, and communication processes: a theory of media synchronicity. MIS Q. 32, 575–600 (2008).

Kelly, J. Here are the companies leading the work-from-home revolution. Forbes (24 May 2020).

Salter, A. & Gann, D. Sources of ideas for innovation in engineering design. Res. Pol. 32, 1309–1324 (2003).

Anderson, M. C. & Spellman, B. A. On the status of inhibitory mechanisms in cognition: memory retrieval as a model case. Psychol. Rev. 102, 68–100 (1995).

Derryberry, D. & Tucker, D. M. In The Heart’s Eye: Emotional Influences in Perception and Attention (eds Niedenthal, P. M. & Kitayama, S.) 167–196 (Academic, 1994).

Posner, M. I. Cognitive Neuroscience of Attention (Guilford Press, 2011).

Rowe, G., Hirsh, J. B. & Anderson, A. K. Positive affect increases the breadth of attentional selection. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 104, 383–388 (2007).

Friedman, R. S., Fishbach, A., Förster, J. & Werth, L. Attentional priming effects on creativity. Creativity Res. J. 15, 277–286 (2003).

Mehta, R. & Zhu, R. J. Blue or red? Exploring the effect of color on cognitive task performances. Science 323, 1226–1229 (2009).

Mednick, S. The associative basis of the creative process. Psychol. Rev. 69, 220–232 (1962).

Nijstad, B. A. & Stroebe, W. How the group affects the mind: a cognitive model of idea generation in groups. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 10, 186–213 (2006).

Jung, R. E., Mead, B. S., Carrasco, J. & Flores, R. A. The structure of creative cognition in the human brain. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 7, 1–13 (2013).

Simon, H. A. A behavioral model of rational choice. Q. J. Econ. 69, 99–118 (1955).

Diehl, M. & Stroebe, W. Productivity loss in brainstorming groups: toward the solution of a riddle. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 3, 497–509 (1987).

Osborne, A. F. Applied Imagination (Scribner, 1957).

Mullen, B., Johnson, C. & Salas, E. Productivity loss in brainstorming groups: a meta-analytic integration. Basic Appl. Soc. Psychol. 12, 3–23 (1991).

Luo, L. & Toubia, O. Improving online idea generation platforms and customizing the task structure on the basis of consumers’ domain-specific knowledge. J. Mark. 79, 100–114 (2015).

Keum, D. D. & See, K. E. The influence of hierarchy on idea generation and selection in the innovation process. Organ. Sci. 28, 653–669 (2017).

Berg, J. M. Balancing on the creative highwire: forecasting the success of novel ideas in organizations. Admin. Sci. Q. 61, 433–468 (2016).

Gray, K. et al. “Forward Flow”: a new measure to quantify free thought and predict creativity. Am. Psychol. 74, 539–55416 (2019).

West, M. A. The social psychology of innovation in groups. in Innovation and Creativity at Work (eds West, M. A. & Farr, J. L.) 309–322 (John Wiley & Sons, 1990).

Nemiro, J. E. Connection in creative virtual teams. J. Behav. Appl. Manage. 2, 93–115 (2016).

Sprecher, S. Initial interactions online-text, online-audio, online-video, or face-to-face: effects of modality on liking, closeness, and other interpersonal outcomes. Comput. Hum. Behav. 31, 190–197 (2014).

Tausczik, Y. R. & Pennebaker, J. W. The psychological meaning of words: LIWC and computerized text analysis methods. J. Lang. Soc. Psychol. 29, 24–54 (2010).

Chartrand, T. L. & van Baaren, R. Human Mimicry. In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology Vol. 41 (ed. Zanna, M. P.) 219–274 (Academic Press, 2009).

Ireland, M. E. et al. Language style matching predicts relationship initiation and stability. Psychol. Sci. 22, 39–44 (2011).

Kulesza, W. M. et al. The face of the chameleon: the experience of facial mimicry for the mimicker and the mimickee. J. Soc. Psychol. 155, 590–604 (2015).

Amos, B., Ludwiczuk, B. & Satyanarayanan, M. Openface: A general-purpose face recognition library with mobile applications. CMU School of Computer Science 6.2 (2016).

Jokinen, K., Nishida, M. & Yamamoto, S. On eye-gaze and turn-taking. In Proc. 2010 Workshop on Eye Gaze in Intelligent Human Machine Interaction 118–123 (ACM Press, 2010); https://doi.org/10.1145/2002333.2002352.

Boland, J. E., Fonseca, P., Mermelstein, I. & Williamson, M. Zoom disrupts the rhythm of conversation. J. Exp. Psychol. https://doi.org/10.1037/xge0001150 (2021).

Hinds, P. J. & Mortensen, M. Understanding conflict in geographically distributed teams: the moderating effects of shared identity, shared context, and spontaneous communication. Organ. Sci. 16, 290–307 (2005).

Mortensen, M. & Hinds, P. J. Conflict and shared identity in geographically distributed teams. Int. J. Confl. Manage. 12, 212–238 (2001).

Kenny, D. A. Quantitative Methods for social psychology. In Handbook of Social Psychology Vol. 1 (eds Lindzey, G. & Aronson, E.) 487–508 (Random House, 1985).

Brewer, W. F. & Treyens, J. C. Role of schemata in memory for places. Cogn. Psychol. 13, 207–230 (1981).

King-Casas, B. Getting to know you: reputation and trust in a two-person economic exchange. Science 308, 78–83 (2005).

Amabile, M. Social psychology of creativity: a consensual assessment technique. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 43, 997–1013 (1982).

Moreau, C. P. & Dahl, D. W. Designing the solution: the impact of constraints on consumers’ creativity. J. Consum. Res. 32, 13–22 (2005).

Cicchetti, D. V. & Sparrow, S. A. Developing criteria for establishing interrater reliability of specific items: applications to assessment of adaptive behavior. Am. J. Ment. Def. 86, 127–137 (1981).

Acknowledgements

We thank B. Ginn, N. Hall, S. Atwood and M. Nelson for help with data collection; M. Jiang, Y. Mao and B. Chivers for help with data processing; G. Eirich for statistical advice; M. Brucks, K. Duke and A. Galinsky for comments and insights; and J. Pyne and N. Itzikowitz for their partnership.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.S.B. supervised data collection by research assistants at the Stanford Behavior Lab in 2016–2021. M.S.B. and J.L. jointly supervised data collection by the corporate partner at the field sites. These data were analysed by M.S.B. and discussed jointly by both of the authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature thanks Brian Uzzi and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data figures and tables

Extended Data Fig. 1 Materials and example data for room recall measure in the second batch of data collection in the lab.

(a) Photo demonstrating the prop placement in the lab room. Five props were expected (props consistent with a behavioural lab schema): a filing cabinet, folders, a cardboard box, a speaker, and a pencil box; and five props were unexpected (props inconsistent with a behavioural lab schema): a skeleton poster, a large house plant, a bowl of lemons, blue dishes, and yoga ball boxes. (b) Participant example of the data materials. After leaving the lab space, participants recreated the lab room on a piece of paper containing the basic layout of the room and then numbered each element. We then asked participants to list the identity of each element on a Qualtrics survey. A condition- and hypothesis-blind research assistant categorized each listing into one of the ten props and removed any other responses. We then counted how many expected and unexpected props were remembered by each participant.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Room recall mediates the effect of communication modality on idea generation.

This mediation model demonstrates that virtual participants remembered significantly fewer unexpected props in the experiment room and that this explains the effect of virtual interaction on creative idea generation. We ran an OLS regression for the a-link (communication modality predicting average recall of unexpected items per pair, n = 151 pairs, OLS regression, b = 0.42, s.e. = 0.17, t149 = 2.44, P = 0.016), and we ran a Negative Binomial regression for the b-link (number of average unexpected items recalled per pair predicting number of creative ideas generated, n = 151 pairs, Negative Binomial regression, b = 0.08, s.e. = 0.03, z = 2.48, P = 0.013). A mediation analysis with 10,000 nonparametric bootstraps revealed that recall of the room mediated the effect of modality on creative idea generation (95% confidence intervals of the indirect effect = −0.61 to −0.01). The total effect of modality condition on number of creative ideas generated was significant (n = 151 pairs, Negative Binomial regression, b = 0.15, s.e. = 0.07, z = 2.18, P = 0.030), but this effect was attenuated to non-significance when accounting for the unexpected recall mediator (n = 151 pairs, Negative Binomial regression, b = 0.12, s.e. = 0.07, z = 1.73, P = 0.083). See Supplementary Information C for model assumption tests of normality and heteroskedasticity. All tests are two-tailed and there were no adjustments made for multiple comparisons (for a discussion of our rationale, see Supplementary Information S).

Extended Data Fig. 3 Gaze mediates the effect of communication modality on idea generation.

This mediation model demonstrates that virtual participants spent less time looking around the room and that this explains the effect of virtual interaction on creative idea generation. We ran an OLS regression for the a-link (communication modality predicting average room gaze per pair, n = 146 pairs, OLS regression, b = −29.1, s.e. = 5.1, t144 = 5.69, P < 0.001), and we ran a Negative Binomial regression for the b-link (average room gaze per pair predicting number of creative ideas generated, n = 146 pairs, Negative Binomial regression, b = 0.003, s.e. = 0.001, z = 2.34, P = 0.020). A mediation analysis with 10,000 nonparametric bootstraps revealed that recall of the room mediated the effect of modality on creative idea generation (95% confidence intervals of the indirect effect = −1.14 to −0.08). The total effect of modality condition on number of creative ideas generated was significant (n = 146 pairs, Negative Binomial regression, b = 0.17, s.e. = 0.07, z = 2.36, P = 0.019), but this effect was attenuated to non-significance when accounting for the room gaze mediator (n = 146 pairs, Negative Binomial regression, b = 0.09, s.e. = 0.08, z = 1.20, P = 0.231). See Supplementary Information C for model assumption tests of normality and heteroskedasticity. All tests are two-tailed and there were no adjustments made for multiple comparisons (for a discussion of our rationale, see Supplementary Information S).

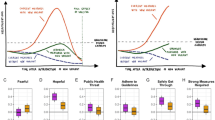

Extended Data Fig. 4 The effect of virtual communication on forward flow across the progression of idea generation.

There was a significant interaction between modality and the position of an idea in the pair’s idea sequence on forward flow score across all studies (linear mixed-effect regression, n = 9966 idea scores, interaction term: b = −0.01, s.e. = 0.01, t358 = −2.09, P = 0.038). At the beginning of the idea generation task, ideas generated by in-person and virtual pairs were similarly connected to past ideas generated by each pair. However, by the eleventh idea, ideas generated by in-person pairs began to exhibit significantly more forward flow (that is, the ideas were less semantically associated) compared to those of virtual pairs (linear mixed-effect regression, n = 9966 idea scores, simple effect of modality on forward flow at the 11th idea: b = −0.12, s.e. = 0.06, t621 = −2.00, P = 0.047). Thus, in-person pairs generate progressively more disconnected ideas relative to virtual pairs. See Supplementary Information D for model assumption tests of normality and heteroskedasticity. We truncated the graph at 30 ideas to provide the most accurate representation of the majority of the data. All tests are two-tailed and there were no adjustments made for multiple comparisons (for a discussion of our rationale, see Supplementary Information S).

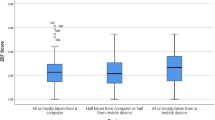

Extended Data Fig. 5 Set-up for group size virtual study.

In the virtual-only study, we randomly assigned participants into groups of 2 or 4 people. Participants worked on a google sheet and were instructed to set up their screen such that half of their screen was the task and the other half of the screen was their zoom window. The self-view was hidden, and participants either saw one partner (2-person condition), or three teammates (4-person condition). Consent was obtained to use these images for publication.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Methods

Sections A–C test the model assumptions. Sections D–J examine the alternative explanations mentioned in the main text and are summarized in Extended Data Figs. 7 and 8. Sections K–M detail additional data and tests examining generalizability. Sections P–Q discuss the limitations. Section R includes secondary analyses in the methods.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Brucks, M.S., Levav, J. Virtual communication curbs creative idea generation. Nature 605, 108–112 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-022-04643-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-022-04643-y

This article is cited by

-

The effect of remote treatment on medical provider creative thinking and patient disclosure: protocol for the MED-CREATE trial

Trials (2025)

-

Mitigation of human cognitive bias in volcanic eruption forecasting

Journal of Applied Volcanology (2025)

-

Video-call glitches trigger uncanniness and harm consequential life outcomes

Nature (2025)

-

A unified framework integrating psychology and geography

Nature Human Behaviour (2025)

-

Reply to: ChatGPT decreases idea diversity in brainstorming

Nature Human Behaviour (2025)