Abstract

Planetary rings are observed not only around giant planets1, but also around small bodies such as the Centaur Chariklo2 and the dwarf planet Haumea3. Up to now, all known dense rings were located close enough to their parent bodies, being inside the Roche limit, where tidal forces prevent material with reasonable densities from aggregating into a satellite. Here we report observations of an inhomogeneous ring around the trans-Neptunian body (50000) Quaoar. This trans-Neptunian object has an estimated radius4 of 555 km and possesses a roughly 80-km satellite5 (Weywot) that orbits at 24 Quaoar radii6,7. The detected ring orbits at 7.4 radii from the central body, which is well outside Quaoar’s classical Roche limit, thus indicating that this limit does not always determine where ring material can survive. Our local collisional simulations show that elastic collisions, based on laboratory experiments8, can maintain a ring far away from the body. Moreover, Quaoar’s ring orbits close to the 1/3 spin–orbit resonance9 with Quaoar, a property shared by Chariklo’s2,10,11 and Haumea’s3 rings, suggesting that this resonance plays a key role in ring confinement for small bodies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

In our efforts to characterize Quaoar’s shape and search for putative material around it, we have predicted and observed several stellar occultations by this body. Following a report from Australia of a Neptune-like ring detected during a 2021 occultation and independently suspected in 2019, we have identified secondary events in previous occultations observed between 2018 and 2020 (Fig. 1, details in Extended Data Table 1, Supplementary Table 1 and Supplementary Fig. 1). They are consistent with a circular ring centred on the body, with two possible mirror solutions for the ring orientation (Methods and Fig. 2). Both solutions have radii close to 4,100 km, or roughly 7.4 Quaoar radii. One solution has a ring pole that presents a large mismatch with Weywot’s orbital pole7, whereas the other solution is consistent with a ring coplanar with Weywot’s orbit (details in Table 1). This is our preferred solution, as a primordial collisional system surrounding Quaoar is expected to settle in a disc that subsequently forms both the ring and Weywot.

The observed flux (black points) and the models (red lines) are plotted against the time relative to the observer closest approach. The blue shaded regions are enlarged in corresponding underlying panels. a–c, The light curve observed by HiPERCAM (is band) on the 10.4 m GTC with the closest approach time at 03:00:31.858 utc (5 June 2019), where b and c contain zoom-in views of the blue regions presented in a. d–f, The light curve observed in Algester by R. Langersek (citizen astronomer) with the closest approach time as 10:59:00.442 utc (27 August 2021), where e and f contain zoom-in views of the blue regions presented in d. No definite detection is made after the closest approach, only an upper limit is derived. More detections are shown in Supplementary Fig. 1.

The occulting chords (green dashed line) and the ring detections with their 1σ error bars (red lines) are plotted for the 2 September 2018, 5 June 2019, 11 June 2020 and 27 August 2021 events. The black ellipses are the two simultaneous best-fitting solutions (Table 1), which are indistinguishable at this scale. The J2000 celestial north and east directions are shown in the upper right corner of each panel. Note that one of the chords in the 11 June 2020 occultations was obtained with CHEOPS space telescope, details in ref. 30.

Each secondary event provides the radial width Wr, a mean normal opacity p and a mean normal optical depth τ of the ring, once projected in the ring plane10,11. These quantities also provide the equivalent width (Ep = pWr) and equivalent depth (Aτ = τWr) of each profile (Methods and Table 1). A noteworthy result is the large variation of Wr and τ observed among detections.

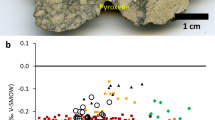

The 5 June 2019 occultation provided the ring profiles in four bands and our data do not show any notable dependence of Ep and Aτ with wavelength. This can be paralleled with multi-wavelength occultations by the core of Saturn’s F ring, indicating that this core contains a substantial population of particles larger than around 10 μm (refs. 12,13,14). Moreover, our numerical integrations show that isolated particles smaller than 100 μm should escape the ring over the time scale of a few years due to radiation pressure (Methods).

Contrary to Chariklo’s ring11, Quaoar’s ring is strongly irregular in azimuth. As such, it is reminiscent of Saturn’s F ring that contains azimuthal features (clumps) or even local opaque structures interpreted as kilometre-sized moonlets15. This clumpy nature is thought to be caused by the presence of thousands of small parent bodies (1.0 to 0.1 km in size) that collide and produce dense strands of micrometre- to centimetre-sized particles that re-accrete over a few months onto the parent bodies in a steady-state regime16,17,18. A similar process may explain the patchy structure of Quaoar’s ring. Another comparison can be made with respect to Neptune’s Adams ring that also shows substantial longitudinal variations in optical depth.

In summary, our observations are consistent with a dense, irregular Quaoar’s ring. The term ‘dense’ means that collisions play a key role in its dynamics. However, in contrast to all other known dense rings, Quaoar’s ring orbits well outside the classical Roche limit. This excludes very tenuous dusty rings with τ < 10−4 seen for instance outside Saturn’s Roche limit19. These tenuous rings are dominated by radiation effects that permanently remove them from their place of formation.

Objects orbiting at distance a from Quaoar with mass MQ should have a density greater than the Roche critical density

to avoid being disrupted by tidal forces. An often-quoted value of γ is 1.6, which would correspond to a lemon-shaped particle aggregate filling its Roche lobe20. Using equation (1) and the values listed in Table 1, we obtain ρRoche ≅ 30 kg m−3, corresponding to extremely porous or even fluffy material.

The dense rings of the giant planets1, as well as Chariklo2 and Haumea3 lie within the Roche limit of the central bodies, assuming ρ = 400 kg m−3, typical of the small inner saturnian satellites21. With this value, Quaoar’s classical Roche limit is near 1,780 km, much smaller than the ring radius of 4,100 km (Table 1 and Extended Data Fig. 2).

Numerical simulations of impact-generated discs show that material outside the Roche limit is expected to accrete over time scales of only a few decades22,23. This rapid processes would indicate a very recent ring and, thus, a very low probability of being observed at the current epoch. That leaves us with a very young or extremely low-density ring particles, or more likely, with the need for revisiting the Roche limit notion. In fact, equation (1) applies to a fluid satellite that is disrupted close to a planet. However, the reverse process—the accretion of colliding particles into a satellite—implies mechanisms not accounted for in equation (1).

Gravitational accretion of ring particles at a given distance depends not only on their bulk density ρ, but also on the radial velocity dispersion c between the particles. If c ≫ vesc, where vesc is the two-body escape velocity of the two ring particles involved in a pairwise impact, these impacts may avoid accretion outside the classical Roche limit. One way to increase the radial velocity dispersion is the ring material to be perturbed by external forces, such as resonances with Quaoar itself, Weywot or undiscovered satellites. Another, is if collisions between pairs are sufficiently elastic to the extent that their postimpact Hill-energies are positive24. In this scenario, the evolution of c is governed by a competition between collisional dissipation and viscous gain of energy from the orbital motion, leading to a steady-state velocity dispersion cst. Its value depends on the relation ϵ(vn) between the collisional coefficient of restitution ϵ and the perpendicular impact velocity between particles, vn. In particular, steeper drops of ϵ versus vn result in smaller values of cst (Fig. 3 and Extended Data Fig. 4).

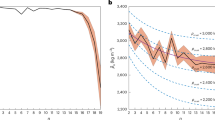

Results of self-gravitating local simulations performed with Quaoar’s mass and ring radius (Table 1) showing the steady-state velocity dispersion cst versus the bulk density ρ of the ring particles with assumed radius of 1 m. We used four velocity-dependent ϵ(vn) models for the coefficient of restitution in impacts, spanning the range of various laboratory experiments of collisions between icy particles. Model 1 stands for frost-covered ice spheres at temperature T = 210 K, \({\epsilon }({v}_{{\rm{n}}})={({v}_{{\rm{n}}}/{v}_{{\rm{c}}})}^{-0.234}\), with vc = 0.0077 cm s−1 (ref. 25); model 2 for frost-covered ice at T = 123 K, \({\epsilon }({v}_{{\rm{n}}})=0.48{{v}_{{\rm{n}}}}^{-0.20}\) (ref. 8); model 3 for as model 1 but with vc = 0.077 cm s−1 and model 4 for particles of radius R = 20 cm with compacted frost at T = 123 K, \({\epsilon }({v}_{{\rm{n}}})=0.90\exp (-0.22{v}_{{\rm{n}}})+0.01{{v}_{{\rm{n}}}}^{-0.6}\) (ref. 8), here vn is the normal component of impact velocity (in cm s−1). Also shown are simulations performed with a constant ϵ = 0.5. The results are shown both in terms of ρ and the dimensionless Hill parameter rH. All simulations have optical depth τ = 0.25, and follow a comoving ring region with a size of 160 × 160 m. Open circles along the lines denote simulations that did not lead to particle aggregation. Filled symbols stand for simulations in which particles accrete to gravity-bound aggregates. The boxes show a snapshot of the comoving ring region with and without the accretion of the particles for models 1 and 4. The shaded region sketches the region where accretion takes place (rH ≳ 1.2, \(c/{v}_{{\rm{e}}{\rm{s}}{\rm{c}}} < 1.65+0.16ln(\rho /80\,{\rm{k}}{\rm{g}}\,{{\rm{m}}}^{-3})\approx 2\)), whereas the dashed line indicates the escape velocity at the surface of 1-m particles for a given bulk density ρ.

Laboratory measurements show that for icy particles, ϵ depends sensitively on their surface properties. Figure 3 shows simulations of particle accretion in Quaoar’s ring with τ = 0.25, with ϵ(vn) models covering the range of existing laboratory measurements. Initial measurements25 with frost-covered ice at temperature T = 210 K (referred to as model 1) suggest that ϵ drops rapidly with vn, attaining values below 0.5 for vn ≅ 1 mm s−1, relevant to Quaoar’s ring (Fig. 3). In this case, cst is of the order of vesc and accretion sets in rapidly in the self-gravitating ring simulations as soon as ρ exceeds ρRoche (Methods). In terms of the non-dimensional rH parameter, defined in equation (8), this corresponds to rH ≅ 1.1–1.2, in agreement with simulations of accretion threshold in Saturn’s rings26.

However, better-controlled experiments8 (referred to as model 4) for particles with compacted-frost surfaces and lower temperatures of 123 K indicated a much shallower ϵ(vn) relationship. In this case the onset of accretion in Quaoar’s ring requires ρcr larger than about 5,000 kg m−3, corresponding to rH > 5. This leaves a safe margin to prevent accretion of icy ring particles with ρ = 400 kg m−3. The reason for this notably different behaviour is the much higher cst maintained by less dissipative impacts.

The accretion limits found above apply to optical depths of τ ≲ 0.25. At larger τ, the steady-state value cst decreases because the reduced mean free path between impacts leads to a less effective viscous gain (Extended Data Fig. 5a). For example, for model 4, the value of cst decreases by a factor of nearly three as τ increases from 0.25 to 1.0, and the minimum value of ρcr required for accretion drops to about 300 kg m−3. This is small, but still in line with the expected density of icy particles. Finally, the critical density ρcr also depends on the particle size R, ρcr increasing as R decreases, making a ring with smaller particles less prone to accretion (Methods and Extended Data Fig. 5b). In summary, there are no objections for having a τ ≲ 0.25 non-accreting ring far outside Quaoar’s classical Roche limit, provided that particles have compacted-frost surfaces described in ref. 8 (model 4).

However, two problems remain concerning the presence of Quaoar’s ring. One is that external perturbations may lead to local condensations. Enhancing τ reduces cst and makes the ring prone to accretion. For example, model 4 with ice particle densities of 400–900 kg m−3 would lead to this type of transition, as accretion is taking place for τ ≳ 1 but not at smaller τ. The other problem is that impacts cause viscous spreading, which needs to be balanced by some mechanism to keep the ring narrow, such as resonances.

Quaoar’s ring is in fact close to both the outer Quaoar 1/3 spin–orbit resonance (SOR) and the inner Weywot 6/1 mean motion resonance (MMR) (Methods and Extended Data Fig. 2). As a small body, Quaoar is expected to have an irregular shape that creates significant SORs stemming from the non-axisymmetric terms of its potential9. A similar configuration is observed around Chariklo’s and Haumea’s rings (Methods), suggesting that the 1/3 SOR may play a key role in the ring confinement.

An assessment of the effect of the 1/3 SOR can be achieved through N-body collisional simulations with a ring that completely surrounds Quaoar. Such simulations applied to Chariklo actually show that the 1/3 SOR not only excites the orbital eccentricities of the particles as expected from equation (11), but also leads to a ring confinement near this resonance27,28. However, these simulations do not account yet for self-gravity. These results are encouraging but they require further simulations using more realistic parameters, as well as theoretical models to understand the confinement mechanism. If confirmed, the 1/3 SOR would play two roles. One is to confine the ring and the other one is to maintain a velocity dispersion between parent bodies or particle aggregates high enough to prevent further accretion.

The 6/1 Weywot MMR is a more complex resonance than the 1/3 Quaoar SOR because it involves one corotation-type resonance and five eccentricity-type resonances (Methods). Their strengths and couplings depend on poorly constrained parameters, that is Weywot’s mass, orbital eccentricity and apsidal precession rate. Our calculations show that the 6/1 corotation resonance creates one L4-type Lagrange point that might concentrate Quaoar’s ring material in a finite interval of longitudes if Weywot’s orbital eccentricity \({e}^{{\prime} }\) is larger than about 0.1. At this stage of knowledge, neither of the two resonances is found to dominate the other. More observations are now necessary to pin down Quaoar’s shape and Weywot’s orbital elements, so as to better constrain the locations and strengths of the resonances that may interact with Quaoar’s ring. Also, new detections of the dense region of the ring can be used to track its motion over time as another way to test models of resonant confinement.

Quaoar’s ring is the third example of a dense ring around a small body found in the Solar System, suggesting that more still await discovery. Meanwhile, the large distance of this ring from Quaoar’s means that the classical notion that dense rings survive only inside the Roche limit of a planetary body must be revised.

Methods

Prediction and observations

The four stellar occultations presented here were predicted using the standard procedures of the European Research Council (ERC) Lucky Star project (https://lesia.obspm.fr/lucky-star) and are publicly available. The stars positions were obtained using Gaia Early Data Release 3 form31. Quaoar’s ephemerides were derived from the numerical integration of the motion of an asteroid32 integrator, taking advantage of Quaoar’s accurate positions derived from previous occultations. For Weywot’s ephemeris, we use the GENOID algorithm (genetic orbit identification7,33) to fit an orbital model on the ten known observations of Weywot between 2006 to 2011 from the Keck observatory6 and from a stellar occultation by Weywot, observed on 4 August 2019. It is a genetics-based algorithm that relies on a meta-heuristic method to find the most appropriate (that is, minimum χ2) set of dynamic parameters. On these data, the best results are from a Keplerian model of Weywot’s motion around Quaoar.

Extended Data Table 1 provides astrometric and photometric information on the occultations and Supplementary Table 1 lists the circumstances of the observations. Ground-based stations and one space-borne instrument (the European Space Agency (ESA)/characterizing exoplanets satellite (CHEOPS) space telescope30) were mobilized.

Data analysis

The images of the occulted stars (plus the occulting object) were analysed applying standard aperture photometry procedures34, using nearby reference stars to correct for sky transparency fluctuations. Secondary events (that is, not caused by Quaoar itself) were observed on 2 September 2018, 5 June 2019, 11 June 2020 and 27 August 2021, showing the presence of a semitransparent ring around Quaoar.

Abrupt opaque edges models, including the effects of diffraction, finite band width, exposure time and the Gaia DR2 stellar diameter, were fitted to the star dis- and re-appearances behind Quaoar’s main body using the procedures in the stellar occultation reduction and analysis (SORA) package35. For the ring events, a further parameter is the apparent ring opacity \({p}^{{\prime} }\) that measures the fractional drop of stellar flux. This parameter is related to the apparent optical depth \({\tau }^{{\prime} }\) by

where ‘apparent’ refers to the quantity measured in the sky plane (ref. 11 and references therein). Knowing the ring pole orientation, these values can be converted to their values normal to the ring plane, p and τ. For cases in which the Airy scale (details in ref. 36) is larger than the width of the ring as seen in the sky plane and assuming a monolayer ring, p is given by

and assuming a polylayer ring, τ is given by37

where B is the ring opening angle, B = 0° (respectively, B = 90°) corresponding to an edge-on (respectively, pole-on) viewing, whereas Quaoar’s ring now has B ≅ −20° (Extended Data Table 2). The integrals of p and τ over the radial width Wr of the rings define the equivalent width Ep = pWr and the equivalent depth Aτ = τWr of the profile. The values of Ep and Aτ are proportional to the amount of material present in the profiles in the monolayer and polylayer cases, respectively10.

If the ring profile is not resolved (that is, drop in flux occurs across fewer than three data points), \({p}^{{\prime} }\) is not known, however, the integral Ep is still measurable10. This applies in the case of the CHEOPS detections that have only one or two data points within the flux drops (Supplementary Fig. 1).

A noteworthy observational result is the large variation of Wr and τ observed among detections. For instance, the 27 August 2021 occultation shows a narrow and dense ring with Wr ≅ 8 km and τ ≅ 0.5. This feature was detected from three different sites, covering about 5.1° along the ring, corresponding to a local and dense ring-arc feature of at least 365 km in length. Conversely, the 5 June 2019 event shows a wider and more transparent feature (Wr ≅ 300 km and τ ≅ 0.014). Meanwhile, the equivalent widths and equivalent depths vary in narrower ranges of about 0.3–1.7 and 0.3–3.8 km, respectively (Table 1 and Extended Data Table 2).

Finally, the timings for the secondary events obtained at the various stations provide their sky-plane positions, to which an elliptical model is fitted using the χ2-statistical test, with

where ri is the observed distance of the ith data point to the ring centre, \({r}_{i}^{{\prime} }\) is the corresponding distance of the model (the ellipse) and σi is the uncertainty on the distance associated with the timing uncertainty of the ith data point. Finally, the σmodel parameter accounts for extra uncertainties associated with our model11,35, stemming in particular from the unknown shape of Quaoar itself, resulting in model bias on its centre position. Considering we have a single chord event that we fit an area equivalent circle of radius 555 km, but Quaoar’s shape may be a Maclaurin spheroid4 with an equatorial radius of 569 km and an oblateness of 0.087, this would cause a bias in the central position typically of roughly 27 km, the value we choose for the σmodel.

Here, we assume that Quaoar’s ring is circular, so that its apparent flattening \({f}^{{\prime} }\) projected in the sky plane is related to its opening angle B through

Assuming that Quaoar’s ring pole orientation has been fixed over the 2018–2021 time interval, we used equation (5) to test a range of pole orientations and ring radii. This provides the two mirror solutions given in Table 1. Both solutions yield a satisfactory fit to the data, with best-fit χ2 value per degree of freedom of \({\chi }_{{\rm{pdf}}}^{2}=0.28\) and \({\chi }_{{\rm{pdf}}}^{2}=1.02\), respectively. Solution 2 corresponds to a ring pole orientation that is consistent with Weywot’s orbital pole orientation to within 6 ± 8°, whereas solution 1 results in a difference of 43 ± 8°. Because we expect the ring and satellite to be coplanar, solution 2 is our preferred one.

In summary, Quaoar’s ring has a normal optical depth τ ranging from 0.004 to 0.77 depending on the longitude (Extended Data Tables 2 and 3). Using an impact frequency of roughly 20τ impacts per particle and per orbit38, this implies that Quaoar’s ring particles suffer between one and ten collisions per revolution, which qualifies this ring as a dense one, that is, a dynamics dominated by collisions. As the viewing geometry of the ring has changed very little between 2018 and 2021, and because of the paucity of observations, it is not possible yet to discriminate between a monolayer or a polylayer ring.

As a first approximation, we can parallel Quaoar ring with Saturn’s rings, in that case, τ ≅ 0.25 corresponds to typical surface densities of Σ ≅ 500 kg m−3 (ref. 39). Adopting a radial width of Wr = 8 km for the densest part of the ring, and considering that the equivalent width of the ring remains roughly constant in longitude (Extended Data Table 2)—so that its mass per unit length is also roughly constant—we obtain a ring mass estimation of Mr = 2πaΣ ≅ 1014 kg, where a ≅ 4,100 km is the ring radius. If accreted into a single satellite with bulk density of 400 kg m−3, typical of the small inner saturnian satellites21, this would yield a body with a radius of the order of 5 km.

Multi-band profiles of the ring from the Gran Telescopio Canarias (GTC)

The 5 June 2019 event was monitored at the 10.4-m GTC with the HiPERCAM instrument, using a four-band system with gs (0.40–0.55 μm), rs (0.550-0.69 μm), is (0.69–0.82 μm) and zs (0.82–1.00 μm) filters40. HiPERCAM also recorded the event in the us-band (0.3–0.4 μm), but the occulted star could not be detected at these wavelengths. Extended Data Fig. 1 shows the light curves obtained in each band, normalized between the unocculted and the zero stellar fluxes, respectively.

As expected, the noise decreases as the wavelength increases because the occulted star is brighter in the red. We fitted the ring parameters for each filter individually (Table 1 and Extended Data Table 2). Even though we are fitting a ring detection with uniform opacity, we note that substructures may exist in some GTC profiles and thus may affect the obtained parameters, although any difference should be within the uncertainty of the parameters. No significant differences between the bands are observed in the parameters at the 3σ confidence level. Also, χ2-tests were performed to compare pairs of observations around the ring detections. The largest difference showed a P value of 0.021, meaning that there is a small 2.1% chance that the light curve obtained with the rs (or zs) filter is different from the gs filter. All the remaining possibilities had a P value smaller than 0.2%.

The absence of wavelength dependence indicates that Quaoar’s ring contains a substantial population of particles larger than around 10 μm (refs. 12,13,14), which is in line with the dense and narrow rings of Saturn, Uranus and Chariklo.

Search for material in other light curves

No light curves besides those described above show significant drops at the times expected from the ring geometry. This essentially stems from the lack of photometric sensitivity and/or temporal resolution of these data. We derived the detection limits provided by these data sets by calculating the standard deviation of the equivalent width

where ϕ(i) is the observed flux and Δr(i) is the radial interval covered by each exposure in the ring plane36.

The limits of detection were evaluated using the data at their original spatial resolutions, and also after a resampling over 300 km windows, which corresponds to the widest ring profile in this project. When applied, resampling allows for increased sensitivity to small variations caused by large, diffuse structures. This procedure consists of applying a Savitsk–Golay digital filter on curves of equivalent width as a function of radial distance in the plane of the ring.

For example, W. Hanna’s data set (27 August 2021) from Yazz had a closest distance approach to Quaoar’s centre of 1,690 km counted in the ring plane and covered a region about 20,000 km before the event, up to 16,000 km after it. Secondary events were not detected up to a 3σ level of Ep = 166 m per data point, with an opaque ring (p = 1) with radial width of roughly 165 m, a semitransparent ring with Wr = 2.7 km and p = 0.06 or any other intermediate solutions. However, a wider and more transparent (p ⩽ 0.01) feature similar to what was observed with the GTC would be lost in the noise. All the obtained upper limits values can be found in Extended Data Table 3.

Besides the four events used here, we also revisited ten other Quaoar occultations observed since 2011 (ref. 41) to search for secondary events. None of them provided data with sufficient quality to detect the ring.

N-body simulations of accretion

We use numerical simulations with the local method in which a comoving ring patch of size 160 × 160 particle radii with periodic boundary conditions is followed to assess the accretion of particles for the proposed Quaoar ring. The particle impacts are calculated with a soft-particle method42. The number of particles is n = 2,000 in simulations with τ = 0.25 and n = 8,000 when τ = 1; here, τ stands for the dynamical optical depth defined as the total cross section of particles divided by the area of the simulated region. Such values of n are sufficient as we are only interested in the onset of accretion, not the subsequent growth or mutual evolution of the aggregates, The advantage of a small n is that we can use a direct particle–particle method for calculation of self-gravity, to ensure that short-range binary interactions are accurately modelled. Typically, simulations lasted for 50–500 orbital periods (corresponding to time scales of a few years).

Several simulations were performed, varying the bulk density of particles ρ, and for a range of elasticity models (below). We used Quaoar’s mass MQ and ring radius a given in Table 1. Identical particles with a radius R = 1 m were assumed in most of our runs. The dimensionless rH parameter characterizes the strength of self-gravity against the tidal force of the planet. It is defined as the ratio of the mutual Hill-radius (RHill) of a pair of particles to the sum of their physical radii,

where \(\mu ={M}_{1}/{M}_{2}={({R}_{1}/{R}_{2})}^{3}\) is the mass ratio of the particles and

If we consider a test particle at rest on the surface of a synchronously rotating spherical large particle (that is, μ = 0), the case rH(0) = 1 corresponds to the limiting case of a zero net attraction (tidal + self-gravity + centrifugal). Thus, in general, accretion (respectively, disruption) of the pair is expected for rH larger (respectively, smaller) than unity. In the case of equal-mass particles (μ = 1), we have

where rH(1) is denoted by rH for simplicity. In the initial state of the simulation the radial velocity dispersion c exceeds by a large factor its steady-state value and also the two-body escape velocity,

During the simulation, c gradually decreases from its initial value due to collisional dissipation, until a steady-state value cst is reached, when the dissipation and viscous gain balance each other, or until c drops to about 2vesc, in which case the particles start to accrete and rapidly coalesce into a single aggregate (Extended Data Fig. 3). This transition from non-accreting to accreting behaviour is very sharp when ρ is increased. In case of accretion, we record the value of c at the onset of aggregate growth, in practice at the instant when the impact frequency had sharply increased twofold compared to its average value. Usually, the aggregate becomes visually evident within one orbital period from this instant of time.

Elasticity models

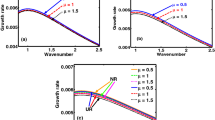

Extended Data Fig. 4 shows the ϵ(vn) models used in our simulations. It also shows the theoretical relation between optical depth τ and the critical ϵcr required for a balance between dissipation and viscous gain of energy43. The cst depends on the ϵ(vn) model through the ϵcr(τ) relation and is independent of R as long as systems with cst ≫ Rn are considered.

The specific values used in simulations, τ = 0.25 and τ = 1.0, are highlighted and the corresponding values of ϵcr(τ) are marked on the left-hand plot. The small downward arrows for model 4 illustrate the expected drop in the average steady-state vn (proportional to cst) when optical depth increases: basically, this drop follows from less effective viscous gain at large τ due the reduction of mean free path between impacts. Similarly, for a fixed τ, the models 3, 2 and 1 indicate successively smaller average vns and cst (refs. 44,45).

Accretion in simulations

The classical Roche limit applies for tidal disruption of a fluid satellite when brought gradually closer to the central body. It can be written in the form of Roche critical density for a given distance (equation (1)), where γ = 0.849, as in the original analysis by Roche46. However, besides a and ρ, the accretion of ring particles also depends on c, and thereby on the elasticity of particles.

Previous local N-body simulations26 explored the onset of particle accretion in Saturn’s rings, using both constant ϵ and the ϵ(vn) relationship of model 1 (ref. 25). The dependence on distance and bulk density was parameterized with the rH parameter (equation (8)). These simulations showed that rH > 1.1 − 1.2 leads to accretion: the upper value is for identical frictionless particles such as in the current experiments, whereas the lower value includes simulations with friction and/or particle size distribution. Note that the above condition for accretion is more stringent than the tidal destruction limit γ = 1.6 usually adopted (ref. 20), which corresponds to rH > 0.87. However, it is close to the classical value γ = 0.849, which corresponds to rH > 1.07.

All simulations of ref. 26 were limited to elasticity models (constant ϵ ≤ 0.5 or the relationship ϵ(vn) of model 1), which correspond to fairly inelastic particles. In this case, the balance between dissipation and viscous gain leads to small velocity dispersion for all ring optical depths. In particular, the velocity dispersion maintained by impacts alone is between roughly 2Rn and 3Rn (where n is the mean motion) and is of the same order as the two-body escape velocity.

However, these highly dissipative models were compared in ref. 45 to affect models with more elastic particles, and corresponding to our model 4 (based on Fig. 22 in ref. 8). In this case, no accretion was possible even with rH = 1.23, which was the largest value explored. This stems from the high velocity dispersion that now exceeds the two-body escape velocity by a large margin.

The simulations presented here extend these studies to larger rH. The behaviour in N-body simulations is also consistent with three-body integrations24 that indicate that the probability of sticking in binary impacts increases rapidly when rH ≳ 1.2. The three-body integrations (fig. 14.18 in ref. 44) also indicate that for large rH, the accretion probability goes rapidly down when impact velocities exceed two-body escape velocity, in agreement with our current N-body experiments.

The dynamical environment of Quaoar’s ring

Table 1 lists the orbital radii of the 1/3 SOR with Quaoar and the 6/1 MMR with Weywot, assuming Keplerian motion around a spherical Quaoar of mass MQ. The error bars on the resonance locations are dominated by the uncertainty on MQ. Accounting for a possible large oblateness of Quaoar would shift these locations by only a few kilometres, leaving our conclusions unchanged. Moreover, Quaoar’s rotational light curves yield two possible rotation periods29. The short rotation period (8.8394 ± 0.0002 h) would correspond to a single-peaked light curve, which would be caused by an oblate body with albedo features on its surface. However, we know that Quaoar cannot be an oblate spheroid but a triaxial ellipsoid due to the varying projected shape of the main body that we have determined in several stellar occultations by Quaoar (whose analysis is beyond the scope of this paper). Because triaxial ellipsoids give rise to double-peaked light curves, the preferred rotation period is 17.6788 ± 0.0004 h. Besides, this double-peaked solution provided a better fit to the photometric data29.

The first-order (in the particle orbital eccentricity) SOR resonances—also called Lindblad resonances—exert torques that clear over short time scales (a few Myr) the region straddling the corotation region near 2,020 km, where the orbital period of the particles matches the rotation period of the body9. This clearing proceeds up to the outermost 1/2 Lindblad resonance near 3,200 km. Moving outwards the next resonance is the second-order 1/3 SOR, that occurs at a semimajor axis of a1/3 = 4,197 ± 58 km. This matches within the error bars with the two possible solutions for the ring orbital radius aR1 = 4,097.3 ± 9.5 km and aR2 = 4,148.4 ± 7.4 km, at the 1.7 and 0.9σ levels, respectively. Similarly, the 6/1 Weywot MMR is at a6/1 = 4,021 ± 57 km, again matching the two solutions aR1 and aR2, at the 1.2 and 2.1σ levels, respectively.

We note that the two ring systems discovered around Chariklo and Haumea orbit also near the 1/3 SOR with their central bodies. For Chariklo, a1/3 = 408 ± 20 km (ref. 47), whereas its two rings orbit at 386 and 400 km from the body11. Similarly, for Haumea we have a1/3 = 2,285 ± 8 km, whereas the ring orbits at \(2,28{7}_{-45}^{+75}\) km (ref. 3).

Using equation (1) and ρ = 400 kg m−3, typical of the small inner saturnian satellites21, we obtain a Quaoar’s Roche limit near 1,780 km. Finally, the Quaoar corotation (or synchronous) orbit is at 2,018 ± 28 km. Extended Data Fig. 2 summarizes the various radii of interest mentioned here.

We now consider resonances between a massless ring particle and either a Quaoar’s mass anomaly or Weywot. For simplicity, Quaoar’s mass anomaly is described as a hemispheric mountain at the surface of the body (main text), however, it may also be an internal feature within an otherwise oblate, smooth body. We denote a, e, λ, ϖ, n and \(\kappa =n-{\mathop{\varpi }\limits^{^\circ }}^{{\prime} }\) the semimajor axis, orbital eccentricity, mean longitude, longitude of pericentre, mean motion and epicyclic frequency of the particle, respectively. Depending on the case, \({\lambda }^{{\prime} }\) is the orientation of Quaoar’s mass anomaly or Weywot’s mean longitude, whereas \({n}^{{\prime} }\) is either Quaoar’s spin rate or Weywot’s mean motion. In the case of Weywot, the orbital eccentricity and the longitude of pericentre of the satellite, \({e}^{{\prime} }\) and \({\varpi }^{{\prime} }\), must also be accounted for (contrarily to the mass anomaly, as the latter moves along a circle). Then \({\kappa }^{{\prime} }={n}^{{\prime} }-{\mathop{\varpi }\limits^{^\circ }}^{{\prime} }\) is Weywot’s epicyclic frequency. The quantities a0 and n0 are the radius and the mean motion at exact resonance. Finally, Quaoar’s and Weywot’s mass anomaly are denoted by μQ and μW, respectively, both normalized to Quaoar’s mass.

We consider the resonance condition \({n}_{0}/{n}^{{\prime} }=m/(m-j)\), where m is a positive or negative integer and j is positive. This resonance splits into j + 1 resonances, each described by a Hamiltonian of the form

where \({\psi }_{k}=m{\lambda }^{{\prime} }-(m-j)\lambda -k\varpi -(j-k){\varpi }^{{\prime} }\), and where k = 0,...j is the order of the resonance in the particle’s eccentricity. The case k = 0 corresponds to a corotation-type resonance with critical angle \({\phi }_{0}={\psi }_{0}=m{\lambda }^{{\prime} }-(m-j)\lambda -j{\varpi }^{{\prime} }\), whereas the cases k ≠ 0 correspond to eccentricity-type resonances with critical angles ϕk = ψk/k.

Each value of k is in fact associated with a MMR \({n}_{0}/{n}^{{\prime} }=(m-j+k)/(m-j)\) of the order k between the particle and a potential moving at the pattern speed

For k ≠ 0, we define the eccentricity vector as \((X,Y)=[e\cos ({\phi }_{k})\), \(e\cos ({\phi }_{k})]\) where e2 = X2 + Y2. The Hamiltonian \({\mathcal{H}}\) is parameterized by the Jacobi constant

where Δa = a − a0 is the distance to the resonance. Particles with the same value of ΔJ but different initial conditions for (X, Y) follow level curves of \({\mathcal{H}}\) under the Hamiltonian flow \(\mathop{X}\limits^{^\circ }=-\partial {\mathcal{H}}/\partial Y\) and \(\mathop{Y}\limits^{^\circ }=+\partial {\mathcal{H}}/\partial X\), eventually forming the phase portrait of the resonance.

The resonant forcing is encapsulated in the perturbing term containing ϵk in the right-hand side of equation (10), not to be confused with the coefficient of restitution ϵ used in the main text and in the section N-body simulations of accretion. It is proportional to μQ or μW, and its numerical values is derived from expansion of the disturbing potential of the mass anomaly48 or the satellite49.

The 1/3 SOR

The 1/3 SOR resonance corresponds to m = −1 and j = 2 in equation (10), so that n/Ω = 1/3, where the pattern speed Ω is Quaoar’s spin rate. Because the mass anomaly moves on a circle, only the resonance k = j (equal to 2 here) is allowed, so that

where the subscript 1/3 refers to the 1/3 SOR, and where we have omitted, for brevity, the index k = 2 that should appear for the coefficient ϵ. Similarly, the resonant angle is denoted \({\phi }_{1/3}=(-{\lambda }^{{\prime} }+3\lambda -2\varpi )/2\), and ΔJ = (Δa/a1/3 − (3/2)e2)/2. From the expression of \({\mathcal{H}}(X,Y;\Delta J)\), it results that for an interval of ΔJ of width 8∣ϵ1/3∣/9 centred on the resonance, the origin (X, Y) = (0, 0) of the phase portrait is a fixed hyperbolic (and thus unstable) point. Collisions tend to damp the eccentricities, that is, force the particles to move towards the origin of the phase portrait (that is, on circular orbits). Conversely, in the interval mentioned above, the resonance tends to force them to follow eight-shaped trajectories, and thus, to acquire non-zero eccentricities. From the expression of ΔJ, this happens for a interval of semimajor axes of width W = (16∣ϵ1/3∣/9)a1/3 centred on the resonance value a1/3.

The forced eccentricity then reaches a peak value (Extended Data Fig. 6) of

at a = a1/3(1 − (8/9)ϵ1/3), where we have used the expression of ϵ1/3 in Extended Data Table 4. In the second equation, we have assumed that the mass anomaly takes the form of a hemispheric mountain of height h at Quaoar’s surface (main text).

The peak eccentricity epeak,1/3 tends to maintain a velocity dispersion Δv among the particles or putative parent bodies of Quaoar’s ring (main text). If the motions of these bodies are not coherent, we have

where \({v}_{{\rm{orb}}}=\sqrt{G{M}_{{\rm{Q}}}/{a}_{1/3}}\) is the orbital velocity at the resonance. The escape velocity at the surface of a particle with radius Rp and density ρ is \({v}_{{\rm{esc}}}=\sqrt{8\pi G\rho {R}_{{\rm{p}}}/3}\). Consequently, the velocity dispersion Δv is comparable to vesc for

where we have used equation (11), ρ = 400 kg m−3 and the numerical values of Table 1.

In the presence of collisions, the second-order nature of the 1/3 SOR leads to mathematical difficulties. In particular, the periodic resonant streamlines intersect at one point, even for vanishing eccentricities48. This yields to a multi-valued velocity field and infinite densities, and therefore singularities in the hydrodynamical equations.

Considering the simple case of a mass anomaly in the form of a hemispheric mountain of height h on Quaoar’s surface, the mass anomaly normalized to Quaoar’s mass is \({\mu }_{{\rm{Q}}}={(h/{R}_{{\rm{Q}}})}^{3}/2\), where RQ is Quaoar’s radius. The 1/3 SOR resonance forces an eccentricity epeak,1/3 (equation (11)), which can in turn maintain locally a velocity dispersion among the putative parent bodies in Quaoar’s ring (equation (12)). This velocity dispersion is comparable to the escape velocity at the surface of the parent bodies for a certain value of μQ (equation (13)), or equivalently, for a certain mountain height of

Assuming parent bodies with size Rp ≅ 0.1 km, typical of Saturn’s F ring parent bodies, we obtain h ≅ 10 km. Thus, plausible topographic features on Quaoar are indeed able to maintain a velocity dispersion among the parent bodies that prevent them from accreting near the 1/3 SOR. This is the case a fortiori for ring particle aggregates that have much smaller sizes. This assumes, however, that the resonant responses of the bodies are not coherent. In the opposite case, the velocity dispersion in equation (12) could be largely overestimated.

Meanwhile, more realistic numerical simulations using N-body collisional codes do show that confinement of a collisional disc (without self-gravity) is observed near the 1/3 SOR with Chariklo’s27,28. This confinement is associated with angular momentum flux reversal at certain longitudes of the ring, but is not yet backed up by analytical calculations.

The Weywot 6/1 MMR

The 6/1 MMR Weywot resonance corresponds to m = 6 and j = 5 in equation (10). It splits into six resonances as k takes the values 0,...5, with the respective resonant angles listed in Extended Data Table 4. The associated resonant terms of Weywot’s disturbing potential have amplitudes of the form \({{\epsilon }}_{6/1,k}{{\rm{e}}}^{k}{e}^{{\prime} 5-k}\), where the coefficients ϵ6/1,k are given in Extended Data Table 4.

Corotation resonance

The case k = 0 corresponds to the corotation resonance condition \(n={n}^{{\prime} }+5{\kappa }^{{\prime} }\approx 6{n}^{{\prime} }\). It creates one stable elliptic (L4 or L5-type) Lagrange point and one unstable hyperbolic (L3-type) point. Here we consider the possibility that the accumulation of ring material around the L4 point might explain the longitudinal variability of Quaoar’s ring. Classical calculations provide the full width of the corotation zone:

that corresponds to the spread in semimajor axes of the particles trapped in this corotation resonance. Using the value of ϵ6/1,0 (Extended Data Table 4), a0 ≅ 4,020 km (Table 1), and assuming that Quaoar and Weywot have the same bulk density, we obtain

where RW is Weywot’s radius. Both the quantities RW and \({e}^{{\prime} }\) (Weywot’s orbital eccentricity) are poorly constrained. Assuming the same albedo for Quaoar and Weywot, we obtain RW ≅ 40 km (ref. 5), and Weywot’s orbital solution provides \({e}^{{\prime} } < 0.15\) (using the method presented in ref. 33). The equation above then yields WCOR ≲ 1 km.

This is comparable to the spread in semimajor axis of Neptune’s arcs, which is much smaller than the physical width of Neptune’s ring-like arcs, about 15 km. This is classically explained by the coherent radial motion of Neptune’s arc particles forced by the nearby satellite Galatea50. This process might also apply to Quaoar’s ring, but still remains to be established. Meanwhile, we note that WCOR rapidly decreases with \({e}^{{\prime} }\). For instance, for \({e}^{{\prime} }=0.01\), we obtain WCOR ≅ 1 m, which appears to be too narrow for maintaining an arc structure around Quaoar, as WCOR is then comparable to the expected typical particle sizes.

Lindblad resonance

The resonance with k = 1 corresponds to a Lindblad (first-order) resonance with associated disturbing potential \({{\epsilon }}_{6/1,1}{\rm{e}}{e}^{{\prime} 4}\cos ({\phi }_{6/1,1})\). Technically, it is a 2/1 resonance of the particle with the component of Weywot’s potential that has the pattern speed \({n}^{{\prime} }+2{\kappa }^{{\prime} }\approx 3{n}^{{\prime} }\). The same exercise as for the Quaoar 1/3 SOR, but now considering a first-order resonance, shows that this resonance forces a peak eccentricity for particles that start with a circular orbit of

The value of epeak,6/1 is again poorly constrained. However, we may compare epeak,6/1 and epeak,1/3 (equation (11)) for RW = 40 km and h = 10 km. Then the two values of epeak are comparable for a Weywot’s orbital eccentricity as small as 0.005. In other words, Weywot’s is expected to force eccentricities of the ring at the 6/1 Lindblad resonance that are comparable to or larger than the eccentricities forced by Quaoar’s 1/3 SOR.

Other resonances

The cases k = 2,...5 correspond to four further resonances of orders k in the particle eccentricities. At this stage, it is difficult to assess their interactions and effects on the corotation and Lindblad resonances, and thus, on the ring behaviour. In particular, their mutual radial distances depend on the value of the apsidal precession rate \({\mathop{\varpi }\limits^{^\circ }}^{{\prime} }\), which is unknown. Moreover, their couplings also depend on the value of \({e}^{{\prime} }\), which is largely unconstrained.

The effect of radiation pressure

Even though Quaoar is located in a far away region compared to the giant planets, the weak gravity field of the central body allows micrometric ring particles to be strongly disturbed by the radiation pressure (RP). To first order, this force causes no secular effect in the semimajor axis of the particles, but induces periodic oscillations in the eccentricity. In a first approximation, the maximum eccentricity eRP attained by a particle of radius R, bulk density ρ initially in a circular orbit of radius a is51

where n and nQ are the mean motion of the particle and Quaoar, respectively, \({c}^{{\prime} }\) is the speed of light, F⊙ is the solar flux at Quaoar’s orbit and Qpr is the radiation pressure coefficient, equal to unity for an ideal material.

This equation shows that ring particles smaller than about 25 μm in radius are ejected from the system, whereas grains with radius ≲45 μm reach eccentricities large enough to collide with Quaoar. In fact, particles smaller than 0.2 cm suffer radial excursions that surpass the ring width.

These results are backed up by numerical simulations performed with a modified version of the Mercury package52 that includes the radiation pressure effects. These simulations show that 1 μm particles are ejected from the system in less than a couple of years, whereas those less than or equal to 45 μm do not survive over a few decades. These results show that Quaoar’s ring is likely to be quickly depleted of sub-centimetre grains, in agreement with the GTC multi-filter observations.

Data availability

The observational data that support this paper and other findings of this study are available at the Strasbourg astronomical Data Center (CDS).

Code availability

This research made use of SORA, a python package for stellar occultations reduction and analysis, developed with the support of ERC Lucky Star and LIneA/Brazil, within the collaboration Rio–Paris–Granada teams. Instructions for downloading and installing SORA can be found on Python Package Index (https://pypi.org/project/sora-astro/), on GitHub (https://github.com/riogroup/SORA) and on its online documentation (https://sora.readthedocs.io/). The method and examples of earlier numerical simulations results have been summarized in ref. 45, anybody interested in using this code in collaborative mode can contact H.S. Other specific codes written especially for this project are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Change history

16 January 2024

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-024-07031-w

References

Esposito, L. W. & De Stefano, M. in Planetary Ring Systems (eds Tiscareno, M. S. & Murray, C. D.) 2–29 (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2018).

Braga-Ribas, F. et al. A ring system detected around the Centaur (10199) Chariklo. Nature 508, 72–75 (2014).

Ortiz, J. L. et al. The size, shape, density and ring of the dwarf planet Haumea from a stellar occultation. Nature 550, 219–223 (2017).

Braga-Ribas, F. et al. The size, shape, albedo, density, and atmospheric limit of Transneptunian Object (50000) Quaoar from multi-chord stellar occultations. Astrophys. J. 773, 26 (2013).

Fornasier, S. et al. TNOs are cool: a survey of the trans-Neptunian region. VIII. Combined Herschel PACS and SPIRE observations of nine bright targets at 70-500 μm. Astron. Astrophys. 555, A15 (2015).

Fraser, W., Batygin, K., Brown, M. E. & Bouchez, A. The mass, orbit, and tidal evolution of the Quaoar-Weywot system. Icarus 222, 357–363 (2013).

Vachier, F., Berthier, J. & Marchis, F. Determination of binary asteroid orbits with a genetic-based algorithm. Astron. Astrophys. 543, A68 (2012).

Hatzes, A. P., Brigdes, F. G. & Lin, D. C. N. Collisional properties of ice spheres at low impact velocities. Mon. Not. R. Astr. Soc. 231, 1091–1115 (1988).

Sicardy, B. et al. Ring dynamics around non-axisymmetric bodies with application to Chariklo and Haumea. Nat. Astronomy 3, 146–153 (2019).

Bérard, D. et al. The structure of Chariklo’s rings from stellar occultations. Astron. J. 154, 144 (2017).

Morgado, B. et al. Refined physical parameters for Chariklo’s body and rings from stellar occultations observed between 2013 and 2020. Astron. Astrophys. 652, A141 (2021).

Bosh, A. S., Olkin, C. B., French, R. G. & Nicholson, P. D. Saturn’s F ring: kinematics and particle sizes from stellar occultation studies. Icarus 157, 57–75 (2002).

Harbison, R. A., Nicholson, P. D. & Hedman, M. M. The smallest particles in Saturn’s A and C rings. Icarus 226, 1225–1240 (2013).

Becker, T. M., Colwell, J. E., Esposito, L. W., Attree, N. O. & Murray, C. D. Cassini UVIS solar occultations by Saturn’s F ring and the detection of collision-produced micron-sized dust. Icarus 306, 171–199 (2018).

Murray, C. D. & French, R. S. in Planetary Ring Systems (eds Tiscareno, M. S. & Murray, C. D.) 338–362 (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2018).

Cuzzi, J. N. & Burns, J. A. Charged particle depletion surrounding Saturn’s F ring: evidence for a moonlet belt? Icarus 74, 284–324 (1988).

Poulet, F., Sicardy, B., Nicholson, P. D., Karkoschka, E. & Caldwell, J. Saturn’s ring-plane crossings of August and November 1995: a model for the new F-ring objects. Icarus 144, 135–148 (2000).

Beurle, K. et al. Direct evidence for gravitational instability and moonlet formation in Saturn’s rings. Astrophys. J. Lett. 718, L176–L180 (2010).

Hedman, M. M., Potsberg, F., Hamilton, D. P., Renner, S. & Hsu, H.-W. in Planetary Ring Systems: Properties, Structure, and Evolution (eds Tiscareno, M. S. & Murray, C. D.) Ch. 12, 308–337 (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2018).

Porco, C. C., Thomas, P. C., Weiss, J. W. & Richardson, D. C. Saturn’s small inner satellites: clues to their origins. Science 318, 1602 (2007).

Thomas, P. & Helfenstein, P. The small inner satellites of Saturn: shapes, structures and some implications. Icarus 344, 113355 (2020).

Kokubo, E., Ida, S. & Makino, J. Evolution of a circumterrestrial disk and formation of a single Moon. Icarus 148, 419–436 (2000).

Takeda, T. & Ida, S. Angular momentum transfer in a protolunar disk. Astrophys. J. 560, 514–533 (2001).

Ohtsuki, K. Capture probability of colliding planetesimals: dynamical constraints on accretion of planets, satellites, and ring particles. Icarus 106, 228–246 (1993).

Bridges, F. G., Hatzes, A. & Lin, D. C. N. Structure, stability and evolution of Saturn’s rings. Nature 309, 333–333 (1984).

Karjalainen, R. & Salo, H. Gravitational accretion of particles in Saturn’s rings. Icarus 172, 328–348 (2004).

Salo, H. et al. Resonance confinement of collisional particle rings. European Planetary Science Congress EPSC2021-338 (2021).

Sicardy, B. et al. Rings around small bodies: the 1/3 resonance is key. European Planetary Science Congress EPSC2021-91 (2021).

Ortiz, J. L. et al. Rotational brightness variations in Trans-Neptunian Object 50000 Quaoar. Astron. Astrophys. 409, L13–L16 (2013).

Morgado, B. E. et al. The stellar occultation by the trans-Neptunian object (50000) Quaoar observed by the ESA CHEOPS space telescope. Astron. Astrophys. 664, L15 (2022).

Brown, A. G. A. et al. Gaia Early Data Release 3. Astron. Astrophys. 649, A1 (2021).

Desmars, J. et al. Orbit determination of trans-Neptunian objects and Centaurs for the prediction of stellar occultations. Astron. Astrophys. 584, A96 (2015).

Vachier, F., Carry, B. & Berthier, J. Dynamics of the binary asteroid (379) Huenna. Icarus 382, 115013 (2022).

Assafin, M. et al. PRAIA - platform for reduction of astronomical images automatically. In Proc. Gaia Follow-up Network for the Solar System Objects: Gaia FUN-SSO Workshop Proceedings (eds Tanga, P. & Thuillot, W.) 85–88 (2011).

Gomes-Júnior, A. R. et al. SORA: stellar occultation reduction and analysis. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 511, 1167–1181 (2022).

Boissel, Y. et al. An exploration of Pluto’s environment through stellar occultations. Astron. Astrophys. 561, A144 (2014).

Elliot, J. L., French, R. G., Meech, K. J. & Elias, J. H. Structure of the Uranian rings. I - Square-well model and particle-size constraints. Astron. J. 89, 1587 (1984).

Hämeen-Anttila, K. A. & Salo, H. Generalized Theory of Impacts in Particulate Systems. Earth Moon Planets 62, 47–84 (1993).

Colwell, J. E. et al. in Saturn from Cassini-Huygens (eds Dougherty, M. K. et al.) 375–412 (Springer, 2009).

Dhillon, V. et al. HiPERCAM: a quintuple-beam, high-speed optical imager on the 10.4-m Gran Telescopio Canarias. Mon. Not. R. Astr. Soc. 507, 350–366 (2021).

Braga-Ribas, F. et al. Database on detected stellar occultations by small outer Solar System objects. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 1365, 012024 (2019).

Salo, H. Simulations of dense planetary rings. III. Self-gravitating identical particles. Icarus 117, 287–312 (1995).

Goldreich, P. & Tremaine, S. The velocity dispersion in Saturn’s rings. Icarus 34, 227–239 (1980).

Schmidt, J. et al. in Saturn from Cassini-Huygens (eds Dougherty, M. K. et al.) 413–458 (Springer, 2009).

Salo, H., Ohtsuki, K. & Lewis, M. C. in Planetary ring systems (eds Tiscareno, M. S. & Murray, C. D.) 434–493 (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2018).

Chandrasekhar, S. Ellipsoidal Figures of Equilibrium (Dover, 1987).

Leiva, R. et al. Size and shape of Chariklo from multi-epoch stellar occultations. Astron. J. 154, 159 (2017).

Sicardy, B. Resonances in nonaxisymmetric gravitational potentials. Astron. J. 159, 102 (2020).

Murray, C. D. & Harper, D. Expansion of the planetary disturbing function to eighth order in the individual orbital elements. QMW Maths Notes 15, vii+436 (1993).

de Pater, I., Renner, S., Showalter, M. R. S. & Sicardy, B. in Planetary Ring Systems (eds Tiscareno, M. S. & Murray, C. D.) 112–124 (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2018).

Hamilton, D. P. & Krivov, A. V. Circumplanetary dust dynamics: effects of solar gravity, radiation pressure, planetary oblateness, and electromagnetism. Icarus 123, 503–523 (1996).

Chambers, J. E. A Hybrid symplectic integrator that permits close encounters between massive bodies. Mon. Not. R. Astr. Soc. 304, 793–799 (1999).

Acknowledgements

We dedicate this paper to the memory of our recently deceased friend and colleague, Tom Marsh, who was instrumental in the development of HiPERCAM. This work was carried out under the Lucky Star umbrella that agglomerates the efforts of the Paris, Granada and Rio teams, which is funded by the ERC under the European Community’s H2020 (ERC grant agreement no. 669416). We thank C. D. Murray for help to calculate the expansion of Weywot’s potential to sixth order in eccentricity. Part of the results were obtained using CHEOPS data. CHEOPS is an ESA mission in partnership with Switzerland with important contributions to the payload and the ground segment from Austria, Belgium, France, Germany, Hungary, Italy, Portugal, Spain, Sweden and the UK. The CHEOPS Consortium gratefully acknowledge the support received by all the agencies, offices, universities and industries involved. Their flexibility and willingness to explore new approaches were essential to the success of this mission. The design and construction of HiPERCAM was supported by the ERC under the European Union’s Seventh Framework Programme (FP/2007-2013) under ERC-2013-ADG grant agreement no. 340040 (HiPERCAM). HiPERCAM operations and V.S.D. are funded by the Science and Technology Facilities Council (grant no. ST/V000853/1). The GTC is installed at the Spanish Observatorio del Roque de los Muchachos of the Instituto de Astrofísica de Canarias, on the island of La Palma. This work has made use of data from the ESA mission Gaia (https://www.cosmos.esa.int/gaia), processed by the Gaia Data Processing and Analysis Consortium (DPAC, https://www.cosmos.esa.int/web/gaia/dpac/consortium). This study was financed in part by the National Institute of Science and Technology of the e-Universe project (INCT do e-Universo, CNPq grant no. 465376/2014-2). This study was financed in part by CAPES - Finance Code 001. The following authors acknowledge the respective (1) CNPq grants to B.E.M. no. 150612/2020-6; F.B.-R. no. 314772/2020-0; R.V.-M. no. 307368/2021-1; M.A. nos. 427700/2018-3, 310683/2017-3 and 473002/2013-2; and J.I.B.C. nos. 308150/2016-3 and 305917/2019-6. (2) CAPES/Cofecub grant to B.E.M. no. 394/2016-05. (3) FAPERJ grant no. M.A. E-26/111.488/2013. (4) FAPESP (Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo) grants to A.R.G.-J. no. 2018/11239-8 and R.S. no. 2016/24561-0. (5) CAPES-PrInt Program grant to G.B.-R. no. 88887.310463/2018-00, mobility number 88887.571156/2020-00. (6) DFG (the German Research Foundation) grant to R.S. no. 446102036. P.S-S. and R.D. acknowledge financial support by the Spanish grant no. AYA-RTI2018-098657-J-I00 ‘LEO-SBNAF’ (MCIU/AEI/FEDER, UE). J.L.O., P.S-S., R.D. and N.M. acknowledge financial support from the State Agency for Research of the Spanish MCIU through the ‘Center of Excellence Severo Ochoa’ award for the Instituto de Astrofísica de Andalucía (grant no. SEV-2017-0709), and they also acknowledge the financial support by the Spanish grant nos. AYA-2017-84637-R and PID2020-112789GB-I00, and the Proyectos de Excelencia de la Junta de Andalucía grant nos. 2012-FQM1776 and PY20-01309. G.B-R. and I.P. acknowledge support from CHEOPS ASI-INAF agreement no. 2019-29-HH.0. A.B. was supported by the SNSA. A.C.-C. and T.G.W. acknowledge support from STFC consolidated grant nos. ST/R000824/1 and ST/V000861/1, and UK Space Agency grant no. ST/R003203/1. U.K. and R.B. acknowledge support by The OpenSTEM Laboratories, an initiative funded by the Higher Education Funding Council for England and the Wolfson Foundation. J.W. gratefully acknowledges financial support from the Heising-Simons Foundation, C. Masson and P. A. Gilman for Artemis, the first telescope of the SPECULOOS network situated in Tenerife, Spain. The ULiege’s contribution to SPECULOOS has received funding from the ERC under the European Union’s Seventh Framework Programme (FP/2007-2013) (grant agreement no. 336480/SPECULOOS), from the Balzan Prize and Francqui Foundations, from the Belgian Scientific Research Foundation (F.R.S.-FNRS; grant no. T.0109.20), from the University of Liege and from the ARC grant for Concerted Research Actions financed by the Wallonia-Brussels Federation. TRAPPIST is a project funded by the Belgian Fonds (National) de la Recherche Scientique (F.R.S.-FNRS) under grant no. PDR T.0120.21. TRAPPIST-North is a project funded by the University of Liege, in collaboration with the Cadi Ayyad University of Marrakech (Morocco). E.J. is FNRS Senior Research Associate. This research includes data from observers.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

B.E.M., B.S. and H.S. wrote the paper and made the figures, with substantial contributions from F.B.-R., C.L.P., T.S., R.S. and F.V. F.B.-R., B.S., J.D., J.L.O. and P.S.-S. organized the stellar occultation observational campaigns with the collaboration of W. Beisker and J.L. B.E.M., F.B.-R., C.L.P., M.A. and G.M. analysed the data and obtained the physical parameters presented in the paper, with inputs from B.S., J.L.O., P.S.-S. and R.V.-M. H.S. designed and performed the N-body simulations. B.S., T.S. and R.S. performed dynamical studies presented in this project. F.V. computed Weywot orbital solution used in this project. B.E.M., A.R.G.-J., R.C.B., G.B.-R., F.L.R. and M.A. are the main developers of data analysis software used in this project. R.V.-M., E.F.-V., G.B.-R., B.J.H., M.K., J.I.B.C., R.D. and D. Souami collaborated with the interpretations of the results. F.J. and J.P.T. observed Quaoar occultation on 2 September 2018. F.B.-R., J.L.O, P.S.-S., V.S.D., N.M., E.J., T.R.M., S.P.L., Z.B., R.B., A. Burdanov, M.F., M.G., U.K., D. Sebastian, C.S. and J.W. participated in the observation of Quaoar occultation on 5 June 2019. W. Benz, G.B., I.P., A. Brandeker, A.C.-C., H.G.F., N.H., G.O. and T.G.W. are members of ESA CHEOPS mission that detected Quaoar occultation on 11 June 2020, and the data analysis was done with substantial contributions from A.R.G.-J. J. Broughton, D.H., J. Bradshaw, R.L., D.G., W.H., S.K. and P.N. observed Quaoar occultation on 27 August 2021, where J. Broughton, R.L. and J. Bradshaw detected the dense arc of material within the Quaoar ring. The opportunity to review the results and comment on the manuscript was given to all authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature thanks Leslie Young and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data figures and tables

Extended Data Fig. 1 Multi-band light curve observed by HiPERCAM on 05 June 2019.

The flux observed in the gs, rs, is and zs bands (black points) and the models (red line) vs. time relative to the observer’s closest approach time (03:00:31.858 utc). The blue shaded regions are enlarged in the side panels. Only one common model (the one obtained for is) is plotted as no statistically significant differences are observed between filters (Table 1). Note the increase of the light curve quality with wavelength.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Dynamical environment of Quaoar’s ring.

The inner ellipse is Quaoar’s Roche limit, assuming particles with bulk densities of ρ = 400 kg m−3, see Methods for details. The corotation radius corresponds to the synchronous orbit, where the orbital period of particles matches Quaoar’s rotation period. The blue and green zones delimit the location of the 1/3 Quaoar spin-orbit resonance (SOR) and the 6/1 Weywot mean motion resonance (MMR), respectively (Table 1). The width of each zone represents the 1-sigma uncertainties on the resonance locations, dominated by the uncertainty on Quaoar’s mass. The two outer black ellipses outline the two possible Quaoar ring solution of Table 1.

Extended Data Fig. 3 Examples of Quaoar’s ring time evolution.

The run shown here uses an optical depth τ = 0.25 and the Model 4 for the ϵ(vn)-relation (Extended Data Fig. 4). The curves show the evolution of radial velocity dispersion, labeled according to the bulk density ρ of the particles in kg m−3. The thick black curves indicate that the system has formed a gravitational aggregate. The inserts (160 m × 160 m in size) show snapshots from the ρ = 6, 000 kg m−3 case around the time when accretion begins. The labels indicate the time in units of orbital periods and the impact frequency f in units of impacts/particle/orbital period. Our criterion for detecting accretion is that f is larger than twice the average pre-accretion value of f, which corresponds to 189 orbital periods. For small ρ the steady state cst is practically the same as in the non-gravitating case. The drop of cst with larger ρ’s follows from the pairwise pre-impact acceleration: increased impact speeds reduce the effective ϵ and thus allow for a lower cst (ref. 42).

Extended Data Fig. 4 Various models for the collisional restitution coefficient.

Left: Model 1: Frost-covered ice spheres at temperature T = 210 K, \({\epsilon }({v}_{{\rm{n}}})={({v}_{{\rm{n}}}/{v}_{{\rm{c}}})}^{-0.234}\), with vc = 0.0077 cm s−1 (ref. 25); Model 2: Frost-covered ice at T = 123 K, \({\epsilon }({v}_{{\rm{n}}})=0.48{{v}_{{\rm{n}}}}^{-0.20}\) (ref. 8); Model 3: as Model 1 but with vc = 0.077 cm s−1 (ten times the value of Model 1); Model 4: particles of radius R = 20 cm with compacted frost at T = 123 K, \({\epsilon }({v}_{{\rm{n}}})=0.90\,\exp (-0.22{v}_{{\rm{n}}})+0.01{{v}_{{\rm{n}}}}^{-0.6}\) (ref. 8). Right: Theoretical relation for the dependence of critical coefficient of restitution ϵcr on optical depth, required for the balance between dissipation and the viscous gain of energy due to local viscosity 43. In case of velocity-dependent elasticity, the system adjusts its impact velocities (via velocity dispersion) so that the effective mean ϵ corresponds to the ϵcr(τ). In case of constant ϵ < ϵcr the system flattens to a near-monolayer state with a minimum c ≈ 2 to 3Rn ≈ 0.01 cm s−1R/1 m (where n is the mean motion) determined by the non-local viscous gain associated with the finite size of the particles. If the constant ϵ > ϵcr, no thermal balance is possible and the system disperses via exponentially increasing c.

Extended Data Fig. 5 The influence of optical depth and particle size.

In the upper panel, we show Model 4 simulations with τ = 0.25 and τ = 1.0. In both series of simulations particle size is R = 1 m. The same conventions as in Fig. 3 are used, but now the scale for c is linear, not logarithmic. For larger τ the steady-state velocity dispersion is reduced, and thus the condition cst/vesc ≲ 2 is achieved for smaller ρ. The bottom panel compares the three assumed particle radii (0.33 m, 1 m, and 3 m) on accretion, using a common optical depth of τ = 0.25 and assuming the velocity-dependent elasticity law of Model 2. Since cst is nearly independent of R, the critical density corresponding to cst/vesc ~ 2 scales roughly as ρcr ∝ 1/R2 since \({v}_{{\rm{esc}}}\propto \sqrt{R}\) (eq. (9)). Note that if a constant ϵ ≲ 0.5 is assumed, the particle size has no effect on the accretion limit, since in this case cst scales linearly with R in a similar fashion to vesc

Extended Data Fig. 6 Topology of the Quaoar 1/3 Spin-Orbit Resonance (SOR).

The bottom graph shows the maximum eccentricity \({e}_{\max }\) reached by a particle starting on an initially circular orbit of semi-major axis a perturbed by the Quaoar 1/3 SOR resonance. This resonance is driven by a mass anomaly whose amplitude is quantified by the dimensionless parameter ϵ1/3. The exact resonance radius a1/3 is marked by the dashed vertical tick mark. The top plots show the phase portraits in the eccentricity vector space (X, Y) corresponding to particular values of a, with \(X=e\cos ({\phi }_{1/3})\), \(Y=e\sin ({\phi }_{1/3})\), where e is the orbital eccentricity and \({\phi }_{1/3}=(-{\lambda }^{{\prime} }+3\lambda -2\varpi )/2\) is the resonant critical angle, see Methods for details. In an interval of width W = (16∣ϵ1/3∣/3)a1/3 in semi-major axis centerd on the resonance, the origin of the phase portrait is an unstable hyperbolic point. Particles are then forced to reach a maximum eccentricity \({e}_{\max }=\sqrt{4/3}\sqrt{(W/2-\Delta a)/{a}_{1/3}}\), where Δa = a − a1/3 is the initial distance of the particle to the resonance. The value of \({e}_{\max }\) peaks at \({e}_{{\rm{peak}},1/3}=(8/3)\sqrt{| \,{{\epsilon }}_{1/3}\,| /3}\) for Δa = − (8/9)∣ϵ1/3∣a1/3. Outside this interval, \({e}_{\max }=0\). Units are arbitrary in all the plots.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Table 1 and Fig. 1.

Supplementary Data

Source data for Supplementary Fig. 1.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Morgado, B.E., Sicardy, B., Braga-Ribas, F. et al. A dense ring of the trans-Neptunian object Quaoar outside its Roche limit. Nature 614, 239–243 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-022-05629-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-022-05629-6

This article is cited by

-

Polarimetry of Solar System minor bodies and planets

The Astronomy and Astrophysics Review (2024)

-

Stellar occultations by trans-Neptunian objects

The Astronomy and Astrophysics Review (2024)

-

A planetary ring in a surprising place

Nature (2023)

-

Trojan Asteroid Satellites, Rings, and Activity

Space Science Reviews (2023)