Abstract

The absence of electrical resistance exhibited by superconducting materials would have enormous potential for applications if it existed at ambient temperature and pressure conditions. Despite decades of intense research efforts, such a state has yet to be realized1,2. At ambient pressures, cuprates are the material class exhibiting superconductivity to the highest critical superconducting transition temperatures (Tc), up to about 133 K (refs. 3,4,5). Over the past decade, high-pressure ‘chemical precompression’6,7 of hydrogen-dominant alloys has led the search for high-temperature superconductivity, with demonstrated Tc approaching the freezing point of water in binary hydrides at megabar pressures8,9,10,11,12,13. Ternary hydrogen-rich compounds, such as carbonaceous sulfur hydride, offer an even larger chemical space to potentially improve the properties of superconducting hydrides14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21. Here we report evidence of superconductivity on a nitrogen-doped lutetium hydride with a maximum Tc of 294 K at 10 kbar, that is, superconductivity at room temperature and near-ambient pressures. The compound was synthesized under high-pressure high-temperature conditions and then—after full recoverability—its material and superconducting properties were examined along compression pathways. These include temperature-dependent resistance with and without an applied magnetic field, the magnetization (M) versus magnetic field (H) curve, a.c. and d.c. magnetic susceptibility, as well as heat-capacity measurements. X-ray diffraction (XRD), energy-dispersive X-ray (EDX) and theoretical simulations provide some insight into the stoichiometry of the synthesized material. Nevertheless, further experiments and simulations are needed to determine the exact stoichiometry of hydrogen and nitrogen, and their respective atomistic positions, in a greater effort to further understand the superconducting state of the material.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$32.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 51 print issues and online access

$199.00 per year

only $3.90 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

The authors declare that the data supporting the findings of this study are available in the article and its supplementary information files and from the public link https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7374510. Source data are provided with this paper.

Change history

24 March 2023

In the version of this article initially published, the Figure 2 Source data file was an incorrect version and has now been updated in the HTML version of the article.

01 September 2023

Editor’s Note: Readers are alerted that the reliability of data presented in this manuscript is currently in question. Appropriate editorial action will be taken once this matter is resolved.

07 November 2023

This article has been retracted. Please see the Retraction Notice for more detail: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-023-06774-2

References

Onnes, H. K. The resistance of pure mercury at helium temperatures. Commun. Phys. Lab. Univ. Leiden12, 120 (1911).

Ginzburg, V. L. Nobel Lecture: On superconductivity and superfluidity (what I have and have not managed to do) as well as on the “physical minimum” at the beginning of the XXI century. Rev. Mod. Phys.76, 981–998 (2004).

Bednorz, J. G. & Müller, K. A. Possible high Tc superconductivity in the Ba–La–Cu–O system. Z. Phys. B Condens. Matter64, 189–193 (1986).

Wu, M. K. et al. Superconductivity at 93 K in a new mixed-phase Y-Ba-Cu-O compound system at ambient pressure. Phys. Rev. Lett.58, 908–910 (1987).

Schilling, A., Cantoni, M., Guo, J. D. & Ott, H. R. Superconductivity above 130 K in the Hg–Ba–Ca–Cu–O system. Nature363, 56–58 (1993).

Carlsson, A. E. & Ashcroft, N. W. Approaches for reducing the insulator-metal transition pressure in hydrogen. Phys. Rev. Lett.50, 1305–1308 (1983).

Ashcroft, N. W. Hydrogen dominant metallic alloys: high temperature superconductors? Phys. Rev. Lett.92, 187002 (2004).

Liu, H., Naumov, I. I., Hoffmann, R., Ashcroft, N. W. & Hemley, R. J. Potential high-Tc superconducting lanthanum and yttrium hydrides at high pressure. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci.114, 6990–6995 (2017).

Peng, F. et al. Hydrogen clathrate structures in rare earth hydrides at high pressures: possible route to room-temperature superconductivity. Phys. Rev. Lett.119, 107001 (2017).

Drozdov, A. P. et al. Superconductivity at 250 K in lanthanum hydride under high pressures. Nature569, 528–531 (2019).

Somayazulu, M. et al. Evidence for superconductivity above 260 K in lanthanum superhydride at megabar pressures. Phys. Rev. Lett.122, 27001 (2019).

Snider, E. et al. Synthesis of yttrium superhydride superconductor with a transition temperature up to 262 K by catalytic hydrogenation at high pressures. Phys. Rev. Lett.126, 117003 (2021).

Troyan, I. A. et al. Anomalous high‐temperature superconductivity in YH6. Adv. Mater.33, 2006832 (2021).

Snider, E. et al. Retraction article: Room-temperature superconductivity in a carbonaceous sulfur hydride. Nature586, 373–377 (2020).

Snider, E. et al. Retraction note: Room-temperature superconductivity in a carbonaceous sulfur hydride. Nature610, 804 (2022).

Smith, G. A. et al. Carbon content drives high temperature superconductivity in a carbonaceous sulfur hydride below 100 GPa. Chem. Commun.58, 9064–9067 (2022).

Sun, Y., Lv, J., Xie, Y., Liu, H. & Ma, Y. Route to a superconducting phase above room temperature in electron-doped hydride compounds under high pressure. Phys. Rev. Lett.123, 097001 (2019).

Ge, Y., Zhang, F. & Hemley, R. J. Room-temperature superconductivity in boron- and nitrogen-doped lanthanum superhydride. Phys. Rev. B104, 214505 (2021).

Grockowiak, A. D. et al. Hot hydride superconductivity above 550 K. Front. Electron. Mater.2, 837651 (2022).

Zhang, Z. et al. Design principles for high-temperature superconductors with a hydrogen-based alloy backbone at moderate pressure. Phys. Rev. Lett.128, 047001 (2022).

Di Cataldo, S., Heil, C., von der Linden, W. & Boeri, L. LaBH8: towards high-Tc low-pressure superconductivity in ternary superhydrides. Phys. Rev. B104, L020511 (2021).

Ashcroft, N. W. Metallic hydrogen: a high-temperature superconductor? Phys. Rev. Lett.21, 1748 (1968).

Richardson, C. F. & Ashcroft, N. W. High temperature superconductivity in metallic hydrogen: electron-electron enhancements. Phys. Rev. Lett.78, 118–121 (1997).

Dias, R. P. & Silvera, I. F. Observation of the Wigner-Huntington transition to metallic hydrogen. Science355, 715–718 (2017).

Loubeyre, P., Occelli, F. & Dumas, P. Synchrotron infrared spectroscopic evidence of the probable transition to metal hydrogen. Nature577, 631–635 (2020).

Wang, H., Tse, J. S., Tanaka, K., Iitaka, T. & Ma, Y. Superconductive sodalite-like clathrate calcium hydride at high pressures. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci.109, 6463–6466 (2012).

Drozdov, A. P., Eremets, M. I., Troyan, I. A., Ksenofontov, V. & Shylin, S. I. Conventional superconductivity at 203 kelvin at high pressures in the sulfur hydride system. Nature525, 73–76 (2015).

Bi, T., Zarifi, N., Terpstra, T. & Zurek, E. in Reference Module in Chemistry, Molecular Sciences and Chemical Engineering (Elsevier, 2019).

Hilleke, K. P. & Zurek, E. Tuning chemical precompression: theoretical design and crystal chemistry of novel hydrides in the quest for warm and light superconductivity at ambient pressures. J. Appl. Phys.131, 070901 (2022).

Di Cataldo, S., von der Linden, W. & Boeri, L. First-principles search of hot superconductivity in La-X-H ternary hydrides. npj Comput. Mater.8, 2 (2022).

Di Cataldo, S., Qulaghasi, S., Bachelet, G. B. & Boeri, L. High-Tc superconductivity in doped boron-carbon clathrates. Phys. Rev. B105, 064516 (2022).

Ye, X., Zarifi, N., Zurek, E., Hoffmann, R. & Ashcroft, N. W. High hydrides of scandium under pressure: potential superconductors. J. Phys. Chem. C122, 6298–6309 (2018).

Shannon, R. D. Revised effective ionic radii and systematic studies of interatomic distances in halides and chalcogenides. Acta Crystallogr. A32, 751–767 (1976).

Rumble, J. R. (ed.) CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics 102nd edn (CRC Press/Taylor & Francis, 2021).

Greenwood, N. N. & Earnshaw, A. (eds) Chemistry of the Elements 2nd edn (Butterworth-Heinemann, 1997).

Zhou, D. et al. Superconducting praseodymium superhydrides. Sci. Adv.6, 6849–6877 (2020).

Zhou, D. et al. High-pressure synthesis of magnetic neodymium polyhydrides. J. Am. Chem. Soc.142, 2803–2811 (2020).

Semenok, D. V. et al. Effect of magnetic impurities on superconductivity in LaH10. Adv. Mater.34, 2204038 (2022).

Sun, W., Kuang, X., Keen, H. D. J., Lu, C. & Hermann, A. Second group of high-pressure high-temperature lanthanide polyhydride superconductors. Phys. Rev. B102, 144524 (2020).

Jaroń, T. et al. Synthesis, structure, and electric conductivity of higher hydrides of ytterbium at high pressure. Inorg. Chem.61, 8694–8702 (2022).

Song, H. et al. High Tc superconductivity in heavy rare earth hydrides. Chin. Phys. Lett.38, 107401 (2021).

Cornelius, A. L., Lawler, K. V. & Salamat, A. Understanding hydrogen rich superconductors: importance of effective mass and dirty limit. Preprint at https://doi.org/10.48550/arxiv.2202.04254 (2022).

Dasenbrock-Gammon, N., McBride, R., Yoo, G., Dissanayake, S. & Dias, R. Second harmonic AC calorimetry technique within a diamond anvil cell. Rev. Sci. Instrum.93, 093901 (2022).

Klesnar, H. P. & Rogl, P. Phase relations in the ternary systems rare-earth metal (RE)-boron-nitrogen, where RE = Tb, Dy, Ho, Er, Tm, Lu, Sc and Y. High Temp. High Press.22, 453–457 (1990).

Pebler, A. & Wallace, W. E. Crystal structures of some lanthanide hydrides. J. Phys. Chem.66, 148–151 (1962).

Bonnet, J. E. & Daou, J. N. Rare‐earth dihydride compounds: lattice thermal expansion and investigation of the thermal dissociation. J. Appl. Phys.48, 964–968 (1977).

Weaver, J. H., Rosei, R. & Peterson, D. T. Electronic structure of metal hydrides. I. Optical studies of ScH2, YH2, and LuH2. Phys. Rev. B19, 4855–4866 (1979).

Peterman, D. J., Harmon, B. N., Marchiando, J. & Weaver, J. H. Electronic structure of metal hydrides. II. Band theory of ScH2 and YH2. Phys. Rev. B19, 4867–4875 (1979).

Daou, J. N., Vajda, P., Burger, J. P. & Shaltiel, D. Percolating electrical conductivity in two phased LuH2+x compounds. Europhys. Lett.6, 647–651 (1988).

Daou, J. N., Vajda, P., Burger, J. P. & Shaltiel, D. Percolating electrical conductivity in two phased LuH2+x compounds. Europhys. Lett.8, 587 (1989).

Mansmann, M. & Wallace, W. E. The structure of HoD3. J. Phys.25, 454–459 (1964).

Palasyuk, T. & Tkacz, M. Pressure-induced structural phase transition in rare-earth trihydrides. Part I. (GdH3, HoH3, LuH3). Solid State Commun.133, 481–486 (2005).

Daou, J. N., Lucasson, A., Vajda, P. & Burger, J. P. Observation of the optical and acoustic electron-phonon coupling in Sc, Y and Lu dihydrides and dideuterides by electrical resistivity. J. Phys. F Metal Phys.14, 2983–2993 (1984).

Kataoka, R. et al. The origin of the highly crystallized face-centered cubic YH3 high-pressure phase when quenched to ambient condition. Mater. Today Commun.31, 103265 (2022).

Renaudin, G., Fischer, P. & Yvon, K. Neodymium trihydride, NdH3, with tysonite type structure. J. Alloys Compd.313, L10–L14 (2000).

Villa-Cortés, S. & De la Peña-Seaman, O. Effect of van Hove singularity on the isotope effect and critical temperature of H3S hydride superconductor as a function of pressure. J. Phys. Chem. Solids161, 110451 (2022).

Liang, X. et al. Prediction of high-Tc superconductivity in ternary lanthanum borohydrides. Phys. Rev. B104, 134501 (2021).

Belli, F. & Errea, I. Impact of ionic quantum fluctuations on the thermodynamic stability and superconductivity of. Phys. Rev. B106, 134509 (2022).

Errea, I. Superconducting hydrides on a quantum landscape. J. Phys. Condens. Matter34, 231501 (2022).

Shen, G. et al. Toward an international practical pressure scale: a proposal for an IPPS ruby gauge (IPPS-Ruby2020). High Press. Res.40, 299–314 (2020).

Datchi, F. et al. Optical pressure sensors for high-pressure–high-temperature studies in a diamond anvil cell. High Press. Res.27, 447–463 (2007).

Dias, R. P., Yoo, C.-S., Kim, M. & Tse, J. S. Insulator-metal transition of highly compressed carbon disulfide. Phys. Rev. B84, 144104 (2011).

Li, Y.-S., Borth, R., Hicks, C. W., Mackenzie, A. P. & Nicklas, M. Heat-capacity measurements under uniaxial pressure using a piezo-driven device. Rev. Sci. Instrum.91, 103903 (2020).

Kraftmakher, Y. Modulation Calorimetry. Theory and Applications (Springer, 2004).

Debessai, M., Hamlin, J. J. & Schilling, J. S. Comparison of the pressure dependences of Tc in the trivalent d-electron superconductors Sc, Y, La, and Lu up to megabar pressures. Phys. Rev. B78, 064519 (2008).

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett.77, 3865–3868 (1996).

Giannozzi, P. et al. QUANTUM ESPRESSO: a modular and open-source software project for quantum simulations of materials. J. Phys. Condens. Matter21, 395502 (2009).

Giannozzi, P. et al. Advanced capabilities for materials modelling with Quantum ESPRESSO. J. Phys. Condens. Matter29, 465901 (2017).

van Setten, M. J. et al. The PseudoDojo: training and grading a 85 element optimized norm-conserving pseudopotential table. Comput. Phys. Commun.226, 39–54 (2018).

Dudarev, S. L., Botton, G. A., Savrasov, S. Y., Humphreys, C. J. & Sutton, A. P. Electron-energy-loss spectra and the structural stability of nickel oxide: an LSDA+U study. Phys. Rev. B57, 1505–1509 (1998).

Cococcioni, M. & de Gironcoli, S. Linear response approach to the calculation of the effective interaction parameters in the LDA+U method. Phys. Rev. B71, 035105 (2005).

Topsakal, M. & Wentzcovitch, R. M. Accurate projected augmented wave (PAW) datasets for rare-earth elements (RE = La–Lu). Comput. Mater. Sci.95, 263–270 (2014).

Dal Corso, A. Pseudopotentials periodic table: from H to Pu. Comput. Mater. Sci.95, 337–350 (2014).

Blöchl, P. E. Projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B50, 17953–17979 (1994).

Peterman, D. J., Weaver, J. H. & Peterson, D. T. Electronic structure of metal hydrides. V. x-dependent properties of LaHx (1.9 < ~x < 2.9) and NdHx (2.01 < ~x < ~2.27). Phys. Rev. B23, 3903–3913 (1981).

Knappe, P., Müller, H. & Mayer, H. W. Tetragonal rare earth hydrides REH(D)≈2.33 (RE = La, Ce, Pr, Nd, Sm) and a neutron diffraction study of NdD2.36. J. Less Common Metals95, 323–333 (1983).

Errea, I. et al. Quantum hydrogen-bond symmetrization in the superconducting hydrogen sulfide system. Nature532, 81–84 (2016).

Acknowledgements

We thank B. Brennessel from the Department of Chemistry at the University of Rochester for providing the technical assistance during the XRD and elemental analysis. We thank M. Debessai for his assistance on the coil setup for the magnetic-susceptibility measurements. Also, we thank I. Silvera and I. Hogarth for the useful scientific discussions and R. C. Heist and L. Koelbl for reading through the manuscript and providing valuable suggestions. Preparation of diamond surfaces and EDX measurements were performed in part at the University of Rochester Integrated Nanosystems Center. Computational resources were provided by the Center for Integrated Research Computing at the University of Rochester. This research was supported by NSF grant no. DMR-2046796, Unearthly Materials Inc. and US Department of Energy, Office of Science, Fusion Energy Sciences under award number DE-SC0020340.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

N.D.-G., E.S., R.M. and H.P. contributed equally to this work as co-first authors. E.S., D.D., N.D.-G., R.M., H.P. and R.P.D. contributed to performing the electrical-conductivity measurements. N.D.-G., N.K.-S., S.M., S.E.D. and R.P.D. contributed to performing a.c. magnetic-susceptibility measurements and analysed the data. N.D.-G., R.M. and R.P.D. contributed to performing heat-capacity measurements and the analysis. E.S., N.D.-G., R.M., D.D., H.P. and S.E.D. contributed to performing elemental analysis, EDX studies and XRD measurements. H.P., R.M., S.E.D. and R.P.D. contributed to performing Raman studies and H.P. and R.P.D. analysed the data. S.E.D. and A.S. performed structure analysis. H.P., S.E.D. and R.P.D. performed the magnetization measurements using a PPMS and R.P.D. analysed the data. K.V.L. and A.S. performed the simulations and analysed the data and chemistry protocol. N.D.-G., K.V.L., A.S., S.E.D. and R.P.D. wrote the paper. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript. R.P.D. conceived the project and oversaw the entire project.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The University of Rochester (U of R) has patents pending related to the discoveries of R.P.D. in the field of superconductivity. R.P.D. is a cofounder and chairman of the board of Unearthly Materials Inc. (UM), a Delaware corporation. UM has licensing agreements with U of R related to the patents, proprietary interests and commercialization rights related to the scientific discoveries of R.P.D. UM, U of R and R.P.D. are subject to non-disclosure and confidentiality agreements. A.S. is a cofounder, president, chief executive officer and board member of UM.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This article has been retracted. Please see the retraction notice for more detail:https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-023-06774-2

Extended data figures and tables

Extended Data Fig. 1 Raman spectra.

a, The spectral deconvolution of Raman spectra of compound A on compression. b, The Raman shift versus pressure of compound A at high pressures, indicating the three distinct phases. c, The spectral deconvolution of Raman spectra of compound B on compression.

Extended Data Fig. 2 The heat-capacity setup.

Top, schematic rendering of the new a.c calorimetry technique (not to scale). The sample is surrounded by a NaCl insert with a heater and thermocouple making contact with the sample. a, View of the preparation as seen from the side showing the thermocouple making contact with the sample inside the DAC. b, View of the preparation as seen from the top of the sample area showing the configuration of heater, thermocouple and Pt leads. Bottom left, heat-capacity setup before loading sample. The thermocouple consists of a shorted alumel/chromel pair. The heater pair consists of a shorted metal, nichrome, Ti or Pt. When driven at frequency f, the sample temperature modulates at frequency 2 × ƒ, which manifests as a voltage on the thermocouple pair that can be measured by a lock-in amplifier. Bottom right, after the sample is loaded, in contact with both the heater and the thermocouple, a small piece of NaCl is placed on top to thermally insulate it from the diamond.

Extended Data Fig. 3 Frequency response.

Frequency and current sweeps measured on a heat-capacity setup before running the experiment. The frequency sweep shows the characteristic plateau and the current sweep demonstrates quadratic dependence, as expected from ohmic heating.

Extended Data Fig. 4 Heat capacity.

Specific heat capacity of MgB2 as a function of temperature at 15 kbar and 127 Hz. The superconducting signature is clearly observed at 32 K. Inset, recorded lock-in voltages during the frequency sweeps at 60 K.

Extended Data Fig. 5 a.c. susceptibility data before background subtraction.

Voltage in volts versus temperature plots at different pressures before the background subtraction. Cubic or quadratic polynomial background was used for background subtraction for susceptibility data. This figure shows fittings with cubic or quadratic polynomials indicated by the red lines. For a.c. susceptibility data, the background subtraction was done mainly for visualization purposes.

Extended Data Fig. 6 Further a.c. susceptibility measurements.

a, The a.c. susceptibility in nanovolts versus temperature for a larger sample of the N-doped Lu hydride system at select pressures from run 2, showing large diamagnetic signal of the superconducting transition owing to the large volume of the sample. The superconducting transition shifts rapidly under pressure to lower temperatures. a.c. susceptibility measurements taken over broader temperature ranges for N-doped Lu hydride at 4 kbar (b), 6 kbar (c) and 8 kbar (d). The red line in b–d is the quadratic fit for the background and the insets show the signals with the background subtracted. e, a.c. susceptibility measurements of MgB2 as a function of temperature using exact same coil set up as the test sample.

Extended Data Fig. 7 EDX measurements.

For EDX measurements, samples were prepared by mounting on an aluminium pin mount with double-sided carbon tape. The samples were then imaged using a Zeiss Auriga scanning electron microscope. Regions of interest were chosen by comparing the scanning electron microscopy image to a white-light image taken beforehand. EDX measurements were performed in the Zeiss Auriga scanning electron microscope with a driving energy of 15 kV and collected and analysed using an EDAX detector with the EDAX APEX software. Carbon and aluminium peaks seen in the EDX spectra originating from the carbon tape and aluminium mount required to place the samples into the scanning electron microscope vacuum chamber. EDX measurements provide further evidence for the presence of nitrogen in our samples.

Extended Data Fig. 8 Phonon bands of stoichiometric Lu hydrides.

The calculated phonon band structures of 0 kbar LuH2 in the fluorite structure (a), \(Fm\bar{3}m\) LuH3 (b), LuH in the RS structure (c) and LuH in the ZB structure (d). e, The calculated phonon band structures of 0 kbar LuH2 in the fluorite structure using a triclinic representation of the lattice vectors with x parallel to a and z parallel to c*, as opposed to the more highly symmetric lattice vectors for a primitive cell of a fcc cell; in this representation, the structure is represented with D3d point-group symmetry as opposed to Oh point-group symmetry as in a. f, The calculated phonon band structures of 0 kbar LuH3 using the same triclinic representation of the lattice vectors and point-group symmetry as in e.

Extended Data Fig. 9 Rietveld refinement of site occupancies.

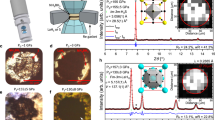

a, Rietveld refinement of the X-ray powder diffraction data collected at 295 K with Cu Kα radiation with refining the occupancy of the tetrahedral interstitial site with N for nitrogen-doped lutetium hydride. b, Simulation of the XRD pattern with Cu Kα wavelength for LuH3 (red), LuH3 with a N replacing a single H in an octahedral site (blue) and a tetrahedral site (green). Rietveld refinement of the X-ray powder diffraction data of ground powder sample was performed with an attempt to investigate the possible N substitution in nitrogen-doped lutetium hydride. We note here that XRD is mostly dominated by heavy Lu atoms.

Extended Data Fig. 10 Projected density of states.

The atom and angular momentum projected partial density of states of LuH2 in the fluorite structure (a); \(Fm\bar{3}m\) LuH3 (b); the cubic cell of \(Fm\bar{3}m\) LuH3 with a N substituted for a H in an octahedral (c) and tetrahedral (d) interstice; and a 2 × 2 × 2 supercell of the rhombohedral primitive cell of \(Fm\bar{3}m\) LuH3 with a N substituted for a H in an octahedral (e) and tetrahedral (f) interstice. In the legends, Oct- means hydrogens in the octahedral interstices and Tet- means hydrogens in the tetrahedral interstices. Each channel is summed over all similar atoms in the unit cell and the plots are scaled to represent a maximum value of 2.5 states eV−1 per formula unit.

Extended Data Fig. 11 Distorted structures predicted by DFT.

a, The distortions to the octahedral hydrogens observed by substituting a N atom for a tetrahedral atom in a single unit cell of \(Fm\bar{3}m\) LuH3. b, The Pmnm LuH3 structure found by perturbing the cubic \(Fm\bar{3}m\) unit cell of LuH3, which suggests possible light-atom positions in phase III. c, The lattice distortions from substituting a N into a tetrahedral interstice in a 2 × 2 × 2 supercell of the rhombohedral primitive of LuH3. d, The lattice distortions from substituting a N into an octahedral interstice in a 2 × 2 × 2 supercell of the rhombohedral primitive of LuH3. The lutetium atoms are green, the nitrogen atoms are lavender and the hydrogen atoms in octahedral interstitial sites are white and those in tetrahedral interstitial sites are pink. In b, there is no distinction made between the hydrogen atom sites, so they are all white.

Extended Data Fig. 12 Superconducting transition widths.

For comparison, the superconducting transition obtained from electrical measurements and a.c. susceptibility measurement at a similar pressure (16 kbar) is shown by red and blue, respectively. The transition width of the resistance drop is 1.3 K and 1.6 K for the a.c. magnetic susceptibility measurement.

Extended Data Fig. 13 Low-temperature electrical-resistance behaviour of N-doped Lu–H systems.

a, The resistance measured on both warming and cooling at about 10 kbar. b, Temperature-dependent electrical resistance of phases I and III, showing the non-superconducting state. c, Four-probe electrical-resistance measurements of different Lu–H–N samples, which consistently shows highly metallic behaviour with decreasing temperature.

Extended Data Fig. 14 Magnetic-susceptibility background and smoothing.

a–c, The ZFC and FC magnetization versus temperature at 8 kbar used to construct Fig. 3a, along with a linear fit to the data at temperatures above the transition temperature, which was used for the background subtraction. d, The ZFC and FC curves with the linear backgrounds shown in b and c subtracted out, as well as with a ten-point adjacent-average smoothing applied. e, The measured cell background at 60 Oe for the HMD cell used for the d.c. measurements.

Extended Data Fig. 15 Electrical-resistance behaviour under magnetic field.

Low-temperature electrical-resistance behaviour under magnetic fields of H = 0 T, 1 T and 3 T (increasing from right to left) at 15 kbar. In this study, the superconductivity of nitrogen-doped lutetium hydride is suppressed by the application of a 3-T external magnetic field, reducing Tc by about 5 K at 15 kbar, further confirming a superconducting transition. The temperature dependence of the resistance of a simple metal is written as: R(T) = Ro + aT2 + bT5. We fit the data below T < 220 K for each field, at which the resistance goes to the minimum value, to that function and subtracted it out. Inset top, the superconducting transition width, ΔTc, at 15 kbar slightly increases under external magnetic fields. The ΔTc has a good linear relationship with the applied magnetic field, as expected from the percolation model. The superconducting transition width is defined here as ΔTc = T90% − T10%, in which T90% and T10% are the temperatures corresponding to 90% and 10% of the resistance at 292 K, respectively. Fitting to the linear relation of ΔTc = ΔTc(0) + kHc2, in which ΔTc(0) is the width at zero external field and k is a constant, provides the values ΔTc(0) = 36.3 K and k = 0.07 KT−1. The large transition width at zero field indicates sample inhomogeneities, which is typical for high-pressure experiments. Inset bottom, the temperature dependence of the upper critical field, \({H}_{{\rm{c}}}\left(T\right)={H}_{{\rm{c}}}\left(0\right)\left[1-{\left(\frac{T}{{T}_{{\rm{c}}}}\right)}^{2}\right]\), can be expressed using GL theory or the conventional Werthamer–Helfand–Hohenberg model. The GL model in the limit of zero temperature yields Hc2(0) ≈ 88 T. From the Werthamer–Helfand–Hohenberg model in the dirty limit, Hc2(0) can be extrapolated from the slope of the H–T curve as \({H}_{{\rm{c2}}}\left(0\right)=0.693{\left|\frac{{{\rm{d}}H}_{{\rm{c}}2}}{{\rm{d}}T}\right|}_{T={T}_{{\rm{c}}}}{T}_{{\rm{c}}}\), which yields roughly 122 T.

Extended Data Fig. 16 Phonon bands of pressurized stoichiometric Lu hydrides.

The calculated phonon band structures of LuH2 in the fluorite structure (left) and LuH in the ZB structure (right) at 0 kbar (top row), 10 kbar (second row), 30 kbar (third row) and 50 kbar (bottom row). The electronic smearing width is 0.005 Ry and the lattice vectors are the highly symmetric ones for a fcc cell. Negligible change in the computed electron–phonon couplings or logarithmic frequency is seen for LuH2 on pressurization.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Video

Notable visual transformation of N-doped lutetium hydride. The high-pressure lutetium–nitrogen–hydrogen system is accompanied by a marked visual transformation over just a few kbar of pressure. The recovered sample is initially in a non-superconducting metallic phase with a lustrous bluish colour, denoted as phase I. Compression to 3 kbar drives the progression of the system into phase II, leading to the superconducting regime, and this transformation is associated with a sudden change in colour from blue to pink. Compression above around 32 kbar drives the sample through another phase transition into phase III. Phase III is a non-superconducting metallic state that is once again distinct in colour, being bright red in appearance.

Theory Plotting Data (ED8)

This file contains source data for Extended Data Fig. 8

Theory Plotting Data (ED10)

This file contains source data for Extended Data Fig. 10

Theory Plotting Data (ED11)

This file contains source data for Extended Data Fig. 11

Theory Plotting Data (ED16)

This file contains source data for Extended Data Fig. 16

Source data

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Dasenbrock-Gammon, N., Snider, E., McBride, R. et al. RETRACTED ARTICLE: Evidence of near-ambient superconductivity in a N-doped lutetium hydride. Nature 615, 244–250 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-023-05742-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-023-05742-0

This article is cited by

-

On the Lineshapes of Temperature-Dependent Transport Measurements of Superconductors Under Pressure

Journal of Superconductivity and Novel Magnetism (2025)

-

Superconductivity researcher who committed misconduct exits university

Nature (2024)

-

The characterization of superconductivity under high pressure

Nature Materials (2024)

-

Superconductivity scandal: the inside story of deception in a rising star’s physics lab

Nature (2024)

-

Temperature and quantum anharmonic lattice effects on stability and superconductivity in lutetium trihydride

Nature Communications (2024)

gorda claire

Looking forward to successful reproduction.

Dmitrii

The authors are famous for manipulation with data in a recently retracted paper in Nature: https://www.nature.com/arti.... They are also famous for publishing an irreproducible result on hydrogen metallization: https://www.science.org/doi.... The authors almost never respond to requests for raw data or samples for independent tests. The last time they provided a small part of the raw data on the "CSH" , the case ended with a retraction of the paper from Nature. You can draw conclusions yourself.

Bartalameo Osanza

Can we please get the complete raw data for figure 2?

The current data for figure 2 is cut to xls format 65534 (who use xls in science?) data points and does not contain superconducting transition for 10 kbar (actual room temperature).

Can we also get raw data for Extended Data Fig 13?

Rafa Replied to Bartalameo Osanza

Agreed. The "background subtraction" for the R vs T measurements (Fig. 2, Extended Data Fig 13, Extended Data Fig. 15) appears to be more than just subtracting a "small residual resistance from the instrument offsets" (quoted from their Methods section); it's a large T-dependent background that they subtract. Why is this justified?

In addition, it is not clear to me how they arrive at the curves in Extended Data Fig 15 from the provided source data (plotted on the left by Bartalameo). In the figure caption, it says they subtract R(T) = Ro + aT^2 + bT^5 for T < 220 K. If one performs this exercise, the background-subtracted data for T > Tc will have negative slope, which is clearly not what is shown in their published figure. So even if this procedure were well justified, something seems off. If any of the co-authors care to elaborate, happy to be corrected...

https://uploads.disquscdn.c...

Bacon Replied to Rafa

If someone fits only their low-T data to a polynomial, then subtracts it, then the low-T data will always have zero resistance and look like a superconductor. That seems like a simple way to assume superconductivity in almost anything.

Bartalameo Osanza Replied to Bartalameo Osanza

I have found full data for fig 2 10 kbar here: https://zenodo.org/record/7...

Rafa Replied to Bartalameo Osanza

It's the full data, but is it the raw data (prior to background subtraction)? It seems likely that the raw data will look something like what they provided for Extended Data Fig. 15 (as you plotted on the left).

Bartalameo Osanza

https://uploads.disquscdn.c...

椎茸うま子

Source data Plotting the ac magnetization using Fig. 3 shows that what appeared to be noise is actually composed of multiple points. If the data is correct, the authors have made an ultra-high precision measurement of 10 pico volts.

https://uploads.disquscdn.c...

Dmitrii Replied to 椎茸うま子

This is impossible, even for 0.5-1 nV it is difficult to do.

椎茸うま子 Replied to Dmitrii

In the case of lock-in measurements, is it possible to have this kind of behavior where data points are hit precisely between the noise?

Dmitrii

Source data for Figure 2. Pay attention to the difference between the measured temperatures (temperature step vs temperature). It looks like a "brick" (left). The data we have recently measured for tin hydride is shown on the right plot. Temperature measurements are voltage measurements on the sensor and such measurements should have the same noise as voltage measurements on the sample.

The data published in this article is not "raw data". The temperature data in the paper are not experimentally measured data. https://uploads.disquscdn.c...

Hans Müller

This case should have consequences for the responsible NATURE editor(s) as well.

How can a lead author, who is known for data fabrication and who had his paper retracted by NATURE last year and who has similar cases of data fabrication in PRL be given another chance to publish in NATURE? How can an author not disclose the raw data when asked to do so? NATURE states that the authors will give out the raw data upon request as a prerequisite to publish in NATURE. It is well known that the authors did not do so in the past, and once more, the key data for figure 2 shows only noise. How can these NATURE write a News and Views that states "doubts remain", yet still publish the paper? What is the review process good for? How can NATURE after seeing that the authors have still linear resistance below T_c and it becomes clear that the authors observe just some phase transition and fabricate the "superconductivity" by some data subtraction not retract the paper immediately? How can it be that authors can not disclose the fabrication methods and experimental details of their paper in NATURE with the hint of business and exploitation? NATURE is in first place a scientific journal, and it should stick to scientific rigor, which includes all informations for others to reproduce and confirm those results.

NATURE and Holtzbrinck should really look into this case, as it shows that NATURE did not stick to its tradition of publishing the best scientific papers. It is on a path to become a megaphon for snake oil salesmen and scam artists, just for the benefit of more clicks. It is time to stop this detrimental pathway.

Bartalameo Osanza Replied to Hans Müller

https://media1.giphy.com/me...

Fawn Rhodes

Regarding the News and View that introduces this paper (https://www.nature.com/arti..., why does the phrase "but doubts remain" only appear in the HTML version, or is it hidden in the PDF version? I hope Nature will maintain its high quality, scientific importance, impact, etc. by being more thoughtful. If Nature agreed to say "but doubts remain" in the article --- even if it is not an original article but a News and Views --- Nature should retract this original article, because ANY doubts should be excluded, carefully discussed and/or explicitly described in THE ORIGINAL PAPER WRITTEN BY THE ORIGINAL AUTHORS, not in other types of articles. Otherwise, the editors of Nature must hesitate to publish a News and View with such a title. This is a very unfortunate situation.

Hans Müller

It is very likely that the two authors of the N&V piece were also referees. This is common policy at the NATURE journals to commission the N&V to an article also to the referees. Of course this is only an indication and no proof. I was wondering who the referees were that let this paper go through. And I am wondering who the handling and thus responsible editor at NATURE was.

Naik Replied to Hans Müller

Nature and Nature Physics are too busy publishing mediocre articles on graphene and other 2D materials. And outside the 2D regime, they have got a reputation of frequently publishing questionable research articles, i.e., majorana (questionable + manipulated data), photo-induced superconductivity (wrong interpretation) and now room-temp superconductivity (everything wrong)

Michael Sentef Replied to Naik

Would you please elaborate on the "wrong interpretation" of the photo-induced superconductivity work?

Dmitry Pesin Replied to Michael Sentef

This is a random guess, but I saw something like that here: https://arxiv.org/abs/1806....

椎茸うま子

Plotting the raw resistance data in Fig. 2, the zero-resistance region for 16 kbar looks like really noisy data, but the high-temperature region seems to have too constant a range of noise at each temperature. Is this possible in a real experiment? I would be happy to hear from anyone who has any insight into this kind of noise.

https://uploads.disquscdn.c...

椎茸うま子 Replied to 椎茸うま子

The first two pictures are histograms of noise on the high-temperature side (first picture) and a histogram of noise on the low-temperature side (second picture) extracted from the raw data. The low-temperature side looks like a natural Gaussian distribution of noise, but the high-temperature side is not a Gaussian distribution. As can be seen from the last one, we can also see that the noise clearly switches at a certain temperature. How is it possible? If anyone has a scientific explanation, I would be very happy to hear it. https://uploads.disquscdn.c... https://uploads.disquscdn.c... https://uploads.disquscdn.c...

椎茸うま子 Replied to 椎茸うま子

If the signal has sin function noise, it may have this inverse sin function noise. Is there a possibility of this kind of noise with lock-in measurement?

Dmitrii Replied to 椎茸うま子

It's unusual distribution. Lock-in measurements also have noise and spikes. The attached picture is an example of lock-in measurements (Standard Research 830 lock-in amplifier). https://uploads.disquscdn.c...

Dmitrii Replied to 椎茸うま子

Very good note! In the normal state, there should also be a noise. I gave two examples for (La,Ce)H9 on attached pictures. On real samples you see noise everywhere. The R(T) data presented by the authors are partially artificial and are not experimental. https://uploads.disquscdn.c... https://uploads.disquscdn.c...

tjmlab

The X-ray diffraction peaks in Figure 5 are all very symmetric. Is this normal?

Note: The right figure was generated by calculating the intensity difference, ΔI(θ_i) = I(θ_i+1) - I(θ_i), for a dataset comprising angle θ and intensity I, and plotting I(θ) - ΔI(θ). If the peak of the intensity is distorted, the ring should also be distorted.

https://uploads.disquscdn.c...

Fawn Rhodes Replied to tjmlab

I think it is possible under excellent experimental conditions (see below). However, what is unclear to me is that they seem to have used a mixture of Kalpha_1 and Kalpha_2 radiations as incident X-rays because you can see two ticks assigned to each Bragg peak. Typically, in conventional laboratory-source X-ray diffractometers such as the ones used in this study, the intensity ratio between them, Kalpha_1/Kalpha_2 is 2, thus the Bragg reflections become asymmetric because of the coexisting two wavelengths of X-rays (note: by using a monochromator (e.g. Ge (111) monochromator. Rigaku synergy has such options), you can selectively use the Kalpha_1 radiation only. They might use this type of monochromator, but then it remains unclear why they put two ticks per Bragg reflection in the figures). Usually, you can clearly see peak splitting originating from the Kalpha_1 - Kalpha_2 coexistence, especially in high-angle regions. From this perspective, their X-ray diffractograms might be "too beautiful", but I think it is early to conclude their XRD patterns are artificial.

Jorge Hirsch

https://uploads.disquscdn.c...

Here is still another "room temperature superconductor" that Ranga Dias has been advertising in talks for the last 2 years. Has anybody seen the paper?

Dmitrii Replied to Jorge Hirsch

Looking forward to the next issue of Nature :)

Hans Müller

Supposedly, it is La_xS_y and Ce_xS_y:

https://imgur.com/a/b0x8pcJ

椎茸うま子

Dear editors and authors

I couldn't find the raw data of Extended data Fig. 13 in Source data or in the repository (https://zenodo.org/record/7.... So please provide the raw data of the Extended data Fig. 13.

In addition, the authors stated, "In some cases, small residual resistance from the instrument offsets was subtracted from the measured voltage." in the electrical-resistance measurements section in the methods. Does this mean that the source data in the repository is data that has already been processed in some way? If so, would it be possible to tell us what processing has been done to the raw data and for which electrical-resistance measurements?

Regards,

Shiitake

Peter Armitage

Hi All,

A number of people's comments are disappearing here. I would suggest the discussion get moved over to Pubpeer, which is exactly for the kind of thing. Please consider reposting some of your material there.

https://pubpeer.com/publica...

Dmitrii

Two recent preprints:

1) Main phase is LuH2, not LuH3.

https://arxiv.org/pdf/2303....

2) LuH2 changes color under pressure. There is no superconductivity in LuH2.

https://arxiv.org/ftp/arxiv...

https://uploads.disquscdn.c... https://uploads.disquscdn.c...

Pham Nam Hai

I have a naive question. In the raw data of the Source Data Extended Data Fig. 5, some voltage signals have the precession of 20 orders of magnitudes (ex. 0.0000121957358521026 V = 121957.358521026 nV). As long as I know, the best nano voltmeter in the market has the precision of 8 orders of magnitude. In order to realize the precision of 20 orders of magnitudes, the nano voltmeter has to have a novel analog-to-digital converter of 46 bits, which has never been heard before. Can anyone comment how to realize this ?

椎茸うま子

Dear editors

By plotting the raw data of Fig. 2, we can see the metallic conduction following a+b*x^2+c*x^3 expression at 100 < T < 173 K for 16 bar data. Then, the resistance drops to the resistance the authors claimed as zero resistance accompanying with some spike noises. However, for me, this feature is reminiscent of a situation where the electrical terminals have short-circuited while the temperature increases. From the raw data of Fig. 2, the low-temperature side of the r-t data ends at various temperatures. We cannot rule out the possibility that a drop from similar metallic conduction to the resistance they claim as zero resistance was also observed in the other data when the temperature increased from the lowest. To examine this point, please request the authors to submit raw data at lower temperatures.

https://uploads.disquscdn.c...

Regards,

Shiitake

Dmitrii

The next experimental refutation:

https://arxiv.org/abs/2303....

https://uploads.disquscdn.c...

https://uploads.disquscdn.c...

DS Replied to Dmitrii

No, that is not a refutation. The authors of the linked preprint have used an entirely different synthesis route. The material thus obtained was reported to have different physical properties and did not exhibit superconductivity under the conditions studied. Up to this point, this is a useful scientific contribution to the debate.

However, the conclusion that this proves the other report (Dasenbrock-Gammon et al.) wrong is based on flawed scientific reasoning and untenable.

Dmitrii Replied to DS

The most clear rebuttal

https://arxiv.org/ftp/arxiv...

Dmitrii

Dias+Salamat do not plan to provide any samples or any additional proofs. If you can't reproduce their "discovery" - that's your problem :)

https://www.science.org/con...

https://uploads.disquscdn.c...

Dmitrii

The results of first principles calculations for the N-doped LuH3-x : there is no high-temperature superconductivity in this class of compounds. Moreover, such compounds are generally not even stable at pressures < 10 GPa.

https://arxiv.org/ftp/arxiv...

Dmitrii

The most clear rebuttal

https://arxiv.org/ftp/arxiv...

https://uploads.disquscdn.c... https://uploads.disquscdn.c... https://uploads.disquscdn.c...

Dmitrii

+1 refutation. No superconductivity in Lu-N-H.

https://arxiv.org/ftp/arxiv...

David

Isn't this an actual retina? There is a thing here in the Netherlands called MabSelect and taken into a similar context the previous question would appear valid. Best regards, David