Abstract

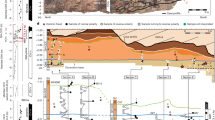

Despite broad agreement that Homo sapiens originated in Africa, considerable uncertainty surrounds specific models of divergence and migration across the continent1. Progress is hampered by a shortage of fossil and genomic data, as well as variability in previous estimates of divergence times1. Here we seek to discriminate among such models by considering linkage disequilibrium and diversity-based statistics, optimized for rapid, complex demographic inference2. We infer detailed demographic models for populations across Africa, including eastern and western representatives, and newly sequenced whole genomes from 44 Nama (Khoe-San) individuals from southern Africa. We infer a reticulated African population history in which present-day population structure dates back to Marine Isotope Stage 5. The earliest population divergence among contemporary populations occurred 120,000 to 135,000 years ago and was preceded by links between two or more weakly differentiated ancestral Homo populations connected by gene flow over hundreds of thousands of years. Such weakly structured stem models explain patterns of polymorphism that had previously been attributed to contributions from archaic hominins in Africa2,3,4,5,6,7. In contrast to models with archaic introgression, we predict that fossil remains from coexisting ancestral populations should be genetically and morphologically similar, and that only an inferred 1–4% of genetic differentiation among contemporary human populations can be attributed to genetic drift between stem populations. We show that model misspecification explains the variation in previous estimates of divergence times, and argue that studying a range of models is key to making robust inferences about deep history.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$32.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 51 print issues and online access

$199.00 per year

only $3.90 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

Nama sequencing data are available from the European Genome-Phenome Archive (EGA), accession number EGAD00001006198. Data access is permitted for non-commercial, population origins or ancestry research upon application to the South African Data Access Committee with appropriate institutional review board approval. The African Diversity Reference Panel can be found at accession EGAS00001000960.

Code availability

Code for the software used in this paper is found at the following locations: moments-LD (https://bitbucket.org/simongravel/moments), Demes (https://github.com/popsim-consortium/demes-python), Relate (https://myersgroup.github.io/relate/), msprime (https://github.com/tskit-dev/msprime) and tskit (https://github.com/tskit-dev/tskit).

Change history

17 July 2023

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-023-06433-6

References

Henn, B. M., Steele, T. E. & Weaver, T. D. Clarifying distinct models of modern human origins in Africa. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 53, 148–156 (2018).

Ragsdale, A. P. & Gravel, S. Models of archaic admixture and recent history from two-locus statistics. PLoS Genet. 15, e1008204 (2019).

Plagnol, V. & Wall, J. D. Possible ancestral structure in human populations. PLoS Genet. 2, e105 (2006).

Hammer, M. F., Woerner, A. E., Mendez, F. L., Watkins, J. C. & Wall, J. D. Genetic evidence for archaic admixture in Africa. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 108, 15123–15128 (2011).

Hey, J. et al. Phylogeny estimation by integration over isolation with migration models. Mol. Biol. Evol. 35, 2805–2818 (2018).

Lorente-Galdos, B. et al. Whole-genome sequence analysis of a pan African set of samples reveals archaic gene flow from an extinct basal population of modern humans into sub-Saharan populations. Genome Biol. 20, 77 (2019).

Durvasula, A. & Sankararaman, S. Recovering signals of ghost archaic introgression in African populations. Sci. Adv. 6, eaax5097 (2020).

Hublin, J.-J. et al. New fossils from Jebel Irhoud, Morocco and the pan-African origin of Homo sapiens. Nature 546, 289–292 (2017).

White, T. D. et al. Pleistocene Homo sapiens from Middle Awash, Ethiopia. Nature 423, 742–747 (2003).

Deacon, H. J. Two Late Pleistocene-Holocene archaeological depositories from the Southern Cape, South Africa. S. Afr. Archaeol. Bull. 50, 121–131 (1995).

Stringer, C. The origin and evolution of Homo sapiens. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 371, 20150237 (2016).

Scerri, E. M. L. et al. Did our species evolve in subdivided populations across Africa, and why does it matter? Trends Ecol. Evol. 33, 582–594 (2018).

Scerri, E. M. L., Chikhi, L. & Thomas, M. G. Beyond multiregional and simple out-of-Africa models of human evolution. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 3, 1370–1372 (2019).

Arredondo, A. et al. Inferring number of populations and changes in connectivity under the n-island model. Heredity 126, 896–912 (2021).

Kamm, J., Terhorst, J., Durbin, R. & Song, Y. S. Efficiently inferring the demographic history of many populations with allele count data. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 115, 1472–1487 (2020).

Speidel, L., Forest, M., Shi, S. & Myers, S. R. A method for genome-wide genealogy estimation for thousands of samples. Nat. Genet. 51, 1321–1329 (2019).

Hsieh, P. et al. Model-based analyses of whole-genome data reveal a complex evolutionary history involving archaic introgression in Central African Pygmies. Genome Res. 26, 291–300 (2016).

The 1000 Genomes Project Consortium. A global reference for human genetic variation. Nature 526, 68–74 (2015).

Lipson, M. et al. Ancient DNA and deep population structure in sub-Saharan African foragers. Nature 603, 290–296 (2022).

Gurdasani, D. et al. The African Genome Variation Project shapes medical genetics in Africa. Nature 517, 327–332 (2015).

Gopalan, S. et al. Hunter-gatherer genomes reveal diverse demographic trajectories during the rise of farming in Eastern Africa. Curr. Biol. 32, 1852–1860 (2022).

Pagani, L. et al. Tracing the route of modern humans out of Africa by using 225 human genome sequences from Ethiopians and Egyptians. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 96, 986–991 (2015).

Prüfer, K. et al. A high-coverage Neandertal genome from Vindija Cave in Croatia. Science 358, 655–658 (2017).

Ragsdale, A. P. & Gravel, S. Unbiased estimation of linkage disequilibrium from unphased data. Mol. Biol. Evol. 37, 923–932 (2020).

Bergström, A., Stringer, C., Hajdinjak, M., Scerri, E. M. L. & Skoglund, P. Origins of modern human ancestry. Nature 590, 229–237 (2021).

Molinaro, L. et al. West Asian sources of the Eurasian component in Ethiopians: a reassessment. Sci. Rep. 9, 18811 (2019).

Henn, B. M. et al. Y-chromosomal evidence of a pastoralist migration through Tanzania to southern Africa. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 105, 10693–10698 (2008).

Breton, G. et al. Lactase persistence alleles reveal partial East African ancestry of southern African Khoe pastoralists. Curr. Biol. 24, 852–858 (2014).

Li, H. & Durbin, R. Inference of human population history from individual whole-genome sequences. Nature 475, 493–496 (2011).

Mazet, O., Rodríguez, W., Grusea, S., Boitard, S. & Chikhi, L. On the importance of being structured: instantaneous coalescence rates and human evolution—lessons for ancestral population size inference? Heredity 116, 362–371 (2016).

Momigliano, P., Florin, A.-B. & Merilä, J. Biases in demographic modeling affect our understanding of recent divergence. Mol. Biol. Evol. 38, 2967–2985 (2021).

Shchur, V., Brandt, D. Y. C., Ilina, A. & Nielsen, R. Estimating population split times and migration rates from historical effective population sizes. Preprint at https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2022.06.17.496540v1 (2022).

Blome, M. W., Cohen, A. S., Tryon, C. A., Brooks, A. S. & Russell, J. The environmental context for the origins of modern human diversity: a synthesis of regional variability in African climate 150,000–30,000 years ago. J. Hum. Evol. 62, 563–592 (2012).

Marean, C. W. et al. in Fynbos (ed. Allsopp, N.) Ch. 8 (Oxford Univ. Press, 2014).

Fu, Q. et al. Genome sequence of a 45,000-year-old modern human from western Siberia. Nature 514, 445–449 (2014).

Groucutt, H. S. et al. Rethinking the dispersal of Homo sapiens out of Africa. Evol. Anthropol. 24, 149–164 (2015).

Prüfer, K. et al. A genome sequence from a modern human skull over 45,000 years old from Zlatý kůň in Czechia. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 5, 820–825 (2021).

Beyer, R. M., Krapp, M., Eriksson, A. & Manica, A. Climatic windows for human migration out of Africa in the past 300,000 years. Nat. Commun. 12, 4889 (2021).

Wall, J. D., Ratan, A., Stawiski, E. & GenomeAsia 100K Consortium. Identification of African-specific admixture between modern and archaic humans. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 105, 1254–1261 (2019).

Grün, R. et al. Dating the skull from Broken Hill, Zambia, and its position in human evolution. Nature 580, 372–375 (2020).

Petr, M., Pääbo, S., Kelso, J. & Vernot, B. Limits of long-term selection against Neandertal introgression. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 116, 1639–1644 (2019).

Zhang, X. et al. The history and evolution of the Denisovan-EPAS1 haplotype in Tibetans. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 118, e2020803118 (2021).

Schrider, D. R. & Kern, A. D. Soft sweeps are the dominant mode of adaptation in the human genome. Mol. Biol. Evol. 34, 1863–1877 (2017).

Relethford, J. H. Craniometric variation among modern human populations. Am. J. Biol. Anthropol. 95, 53–62 (1994).

Weaver, T. D., Roseman, C. C. & Stringer, C. B. Close correspondence between quantitative- and molecular-genetic divergence times for Neandertals and modern humans. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 105, 4645–4649 (2008).

von Cramon-Taubadel, N. Congruence of individual cranial bone morphology and neutral molecular affinity patterns in modern humans. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 140, 205–215 (2009).

Harvati, K. et al. The Later Stone Age calvaria from Iwo Eleru, Nigeria: morphology and chronology. PLoS ONE 6, e24024 (2011).

Crevecoeur, I., Brooks, A., Ribot, I., Cornelissen, E. & Semal, P. Late Stone Age human remains from Ishango (Democratic Republic of Congo): new insights on Late Pleistocene modern human diversity in Africa. J. Hum. Evol. 96, 35–57 (2016).

Crevecoeur, I. in Modern Origins: A North African Perspective (eds. Hublin, J. J. & McPherron, S. P.) 205–219 (Springer, 2012).

Day, M. H. Early Homo sapiens remains from the Omo River region of South-west Ethiopia: Omo human skeletal remains. Nature 222, 1135–1138 (1969).

Vidal, C. M. et al. Age of the oldest known Homo sapiens from eastern Africa. Nature 601, 579–583 (2022).

Richter, D. et al. The age of the hominin fossils from Jebel Irhoud, Morocco, and the origins of the Middle Stone Age. Nature 546, 293–296 (2017).

Berger, L. R. et al. Homo naledi, a new species of the genus Homo from the Dinaledi Chamber, South Africa.eLife 4, e09560 (2015).

Dirks, P. H. et al.The age of Homo naledi and associated sediments in the Rising Star Cave, South Africa.eLife 6, e24231 (2017).

Kelleher, J., Etheridge, A. M. & McVean, G. Efficient coalescent simulation and genealogical analysis for large sample sizes. PLoS Comput. Biol. 12, e1004842 (2016).

Baumdicker, F. et al. Efficient ancestry and mutation simulation with msprime 1.0. Genetics 220, iyab229 (2022).

Acknowledgements

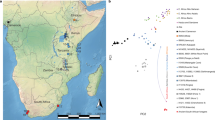

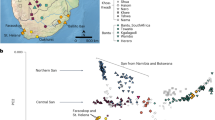

We thank participants for the DNA contributions that enabled this study; in particular, we wish to highlight the generous participation of the Richtersveld Nama community in South Africa and help from local research assistants W. De Klerk and H. Kaimann. Additional assistance and community engagement was conducted by J. Myrick, C. Gignoux, C. Uren and C. Werely. We thank the African Genome Diversity Project for data generation, including T. Carensten, D. Gurdasani and M. Sandhu; L. Anderson-Trocmé and G. Femerling for assistance in creating the map in Fig. 2 and Supplementary Fig. 2, respectively; and N. M. Morales-Garcia for data visualization discussion and designing Figs. 1 and 3. This research was supported by CIHR project grant 437576, Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC) grant RGPIN-2017-04816, the Canada Research Chair program to S.G. and the Canada Foundation for Innovation, and an NIH grant R35GM133531 to B.M.H.; and E.G.A. was supported by NIH K01 MH121659 and K12 GM102778. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. M.M. and E.H. acknowledge the support of the DSI-NRF Centre of Excellence for Biomedical Tuberculosis Research, the South African Medical Research Council Centre for Tuberculosis Research, and the Division of Molecular Biology and Human Genetics at Stellenbosch University, Cape Town, South Africa.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.P.R., B.M.H. and S.G. designed the study. B.M.H., E.H. and M.M. designed recruitment protocols and recruited participants. B.M.H. and E.G.A. performed data quality control. A.P.R., B.M.H. and S.G. designed the statistical analyses. A.P.R. conducted the statistical analyses. A.P.R., T.D.W., B.M.H. and S.G. interpreted the results and wrote the first draft of the article. All authors read and edited the paper.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature thanks Marta Mirazon Lahr and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

This file contains further discussion, methods and data, Supplementary Tables S1–S8, Supplementary Figs. S1–S40, and Supplementary References.

Supplementary Data

This zipped file contains inferred demographic models in Demes format for all models presented in the main text and all alternative models used in validation of our main results that are discussed in the Supplementary Information.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Ragsdale, A.P., Weaver, T.D., Atkinson, E.G. et al. A weakly structured stem for human origins in Africa. Nature 617, 755–763 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-023-06055-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-023-06055-y

This article is cited by

-

Common DNA sequence variation influences epigenetic aging in African populations

Communications Biology (2025)

-

A structured coalescent model reveals deep ancestral structure shared by all modern humans

Nature Genetics (2025)

-

Robust and accurate Bayesian inference of genome-wide genealogies for hundreds of genomes

Nature Genetics (2025)

-

Exploring the mitochondrial DNA ancestry of patients with type 1 diabetes from an admixed population of the Northeast of Brazil

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

Resolving out of Africa event for Papua New Guinean population using neural network

Nature Communications (2025)

aquape

Thanks a lot for this article. An African or Middle-East origin of late-Pleistocene Homo sapiens is well possible (although still not proven IMO), but an African origin of the genus Homo is unlikely, and an African origin of the Hominidae (sensu Gorilla, Homo and Pan) is even less likely. Of the somewhat 28 spp of extant Hominoidea (2 Pan, 1 Homo, 2 Gorilla, 3 Pongo, the rest hylobatids: gibbons and siamang), most live in SE.Asia. Most likely, late-Miocene Hominidae were bipedal, wading-climbing hominids in the swamp forests of the then incipient Red Sea, google "aquarboreal" and see e.g. my recent book "De evolutie van de mens" Academische Uitgeverij Eburon 2022 Utrecht NL pp.299-300 https://www.gondwanatalks.c...

Nicholas Jones

Migration really? How could such brainiacs miss the elephant in the room. Think long distance trade in lithic tools, or the raw materials for that economy to start with. that trade possibly could have booted up several species ago and likely would have been cross-species as well.

aquape

Human Pliocene ancestors were most likely *not* in Africa, see the absence in human genetic material of Pliocene African primate DNA, IOW, "Out of Africa" is a very questionable slogan (anthropocentrism): most likely, at least our Pliocene ancestors were not in Africa, see refs below.

Where mid- or late-Pleistocene H.sapiens originated is uncertain IMO (Middle East?), but there is little doubt that Pliocene Homo lived along the southern Asian coasts, google e.g. "gondwanatalks verhaegen english".

Refs:

- "Lineage-specific expansions of retroviral insertions within the genomes of African great apes but not humans and orangutans" Chris T Yohn cs 2005 PLoS doi org/10.1371/journal.pbio.0030110

- "Evolution of type C viral genes: evidence for an Asian origin of man" Raoul Benveniste & George Todaro 1976 Nature 261:101–8: "... to conclude that most of man's evolution has occurred outside Africa."