Abstract

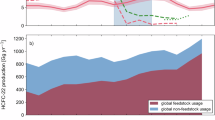

HFC-23 is a potent greenhouse gas, predominantly emitted as an undesired by-product during the synthesis and processing of HCFC-22 (ref. 1). Previously, the Clean Development Mechanism and national efforts called for the implementation of abatement technology for reducing HFC-23 emissions2,3. Nevertheless, between 2015 and 2019, a divergence was found between the global emissions derived from atmospheric observations and those expected from reported abatement1,2. Primarily, this points to insufficient implementation of abatement strategies2,4, calling for independent verification of the emissions at the individual chemical facility level. Here we use regional atmospheric observations and a new, deliberately released tracer to quantify the HFC-23 emissions from an HCFC-22 and fluoropolymer production facility, which is equipped with waste gas destruction technology. We find that our inferred HFC-23/HCFC-22 emission factor of 0.19% (0.13–0.24%) broadly fits within the emission factor considered practicable for abatement projects5,6. Extrapolation to global HCFC-22 production underscores that the operation of appropriate destruction technology has the potential to reduce global HFC-23 emissions by at least 84% (69–100%) (14 (12–16) Gg yr−1). This reduction is equivalent to 17% CO2 emissions from aviation in 2019 (ref. 7). We also demonstrate co-destruction of PFC-318, another by-product and greenhouse gas. Our findings show the importance of the 2016 Kigali Amendment to the Montreal Protocol, which obligates parties to destroy HFC-23 emissions from facilities manufacturing hydrochlorofluorocarbons and hydrofluorocarbons “to the extent practicable” from 2020 onwards8.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$32.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 51 print issues and online access

$199.00 per year

only $3.90 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

Atmospheric measurement data acquired at the Cabauw station for all substances subject to this paper as well as tracer emission rates are available from the Zenodo data repository (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.11208167). HCFC-22 inventory data are available from the Ozone Secretariat (https://ozone.unep.org/). Dutch National Inventory Reports to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change are available from https://unfccc.int/ghg-inventories-annex-i-parties/2023.

References

Liang, Q. et al. in Scientific Assessment of Ozone Depletion: 2022. GAW Report No. 278, Ch. 2 (World Meteorological Organization, 2022).

Stanley, K. M. et al. Increase in global emissions of HFC-23 despite near-total expected reductions. Nat. Commun. 11, 397 (2020).

Miller, B. R. et al. HFC-23 (CHF3) emission trend response to HCFC-22 (CHClF2) production and recent HFC-23 emission abatement measures. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 10, 7875–7890 (2010).

Park, H. et al. A rise in HFC-23 emissions from eastern Asia since 2015. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 23, 9401–9411 (2023).

UNEP. Key Aspects Related to HFC-23 By-product Control Technologies (Decision 83/67(d)). Report No. UNEP/OzL.Pro/ExCom/89/13 (United Nations Environment Programme, 2022).

UNEP. Report of Part II of the Eighty-Ninth Meeting of the Executive Committee. Report No. UNEP/OzL.Pro/ExCom/89/16 (United Nations Environment Programme, 2022).

International Energy Agency. Aviation. IEA https://www.iea.org/reports/aviation (2022).

UNEP. Amendment to the Montreal Protocol on Substances that Deplete the Ozone Layer. United Nations Treaty Collection https://treaties.un.org/Pages/ViewDetails.aspx?src=IND&mtdsg_no=XXVII-2-f&chapter=27&clang=_en (2016).

Myhre, G. et al. in Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change Ch. 8 (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2013).

Oram, D. E., Sturges, W. T., Penkett, S. A., McCulloch, A. & Fraser, P. J. Growth of fluoroform (CHF3, HFC-23) in the background atmosphere. Geophys. Res. Lett. 25, 35–38 (1998).

Miller, B. R. & Kuijpers, L. J. M. Projecting future HFC-23 emissions. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 11, 13259–13267 (2011).

Simmonds, P. G. et al. Recent increases in the atmospheric growth rate and emissions of HFC-23 (CHF3) and the link to HCFC-22 (CHClF2) production. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 18, 4153–4169 (2018).

Rodriguez, M. A., van Dril, T. & Gamboa Palacios, S. Decarbonisation Options for the Dordrecht Chemical Cluster, MIDDEN: Manufacturing Industry Decarbonisation Data Exchange Network (PBL Netherlands Environmental Assessment Agency, 2021).

TEAP. Volume 6: Response to Decision XXXIV/7: Strengthening Institutional Processes with Respect to Information on HFC-23 By-Product Emissions, Report of the Technology and Economic Assessment Panel, Vol. 6 (United Nations Environment Programme, 2023).

Ebnesajjad, S. Fluoroplastics, Vol. 2, Melt Processible Fluoropolymers, The Definitive User’s Guide and Data Book 2nd edn, Ch. 6 (Elsevier, 2015).

Sung, D. J., Moon, D. J., Moon, S., Kim, J. & Hong, S. I. Catalytic pyrolysis of chlorodifluoromethane over metal fluoride catalysts to produce tetrafluoroethylene. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 292, 130–137 (2005).

UNEP. Medical and Technical Options Committee (MCTOC) 2022 Assessment Report (United Nations Environment Programme, 2022).

TEAP. Volume 6: Assessment of the Funding Requirement for the Replenishment of the Multilateral Fund for the Period 2021–2023, Report of the Technology and Economic Assessment Panel (United Nations Environment Programme, 2021).

Pérez-Peña, M. P., Fisher, J. A., Hansen, C. & Kable, S. H. Assessing the atmospheric fate of trifluoroacetaldehyde (CF3CHO) and its potential as a new source of fluoroform (HFC-23) using the AtChem2 box model. Environ. Sci. Atmos. 3, 1767–1777 (2023).

McGillen, M. R. et al. Ozonolysis can produce long-lived greenhouse gases from commercial refrigerants. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 120, e2312714120 (2023).

McCulloch, A. & Lindley, A. A. Global emissions of HFC-23 estimated to year 2015. Atmos. Environ. 41, 1560–1566 (2007).

US EPA. Global Mitigation of Non-CO2 Greenhouse Gases: 2010-2030 (United States Environmental Protection Agency, Office of Atmospheric Programs, 2013).

UNEP. Key Aspects Related to HFC-23 By-Product Control Technologies. Report No. UNEP/OzL.Pro/ExCom/78/9, Vol. 1 (United Nations Environment Programme, 2017).

UNEP. Corrigendum Key Aspects Related to HFC-23 By-Product Control Technologies. Report No. UNEP/OzL.Pro/ExCom/78/9/Corr.1 (United Nations Environment Programme, 2017).

Say, D. et al. Emissions of halocarbons from India inferred through atmospheric measurements. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 19, 9865–9885 (2019).

UNEP. Key Aspects Related to HFC-23 By-product Control Technologies (Decision 78/5). Report No. UNEP/OzL.Pro/ExCom/79/48 (United Nations Environment Programme, 2017).

UNEP. Cost-Effective Options for Controlling HFC-23 By-Product Emissions (Decision 81/68(e)). Report No. UNEP/OzL.Pro/ExCom/82/68 (United Nations Environment Programme, 2018).

UNEP. Corrigendum: Cost-effective Options for Controlling HFC-23 By-Product Emissions (Decision 81/68(e)). Report No. UNEP/OzL.Pro/ExCom/82/68/Corr.1 (United Nations Environment Programme, 2018).

UNEP. Report of the Sub-group on the Production Sector. Report No. UNEP/OzL.Pro/ExCom/84/74* (United Nations Environment Programme, 2019).

MEFCC. Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change. Order No. F. No. 10/29/2014-OC (Ozone Cell, 2016).

UNEP. Key Aspects Related to HFC-23 By-product Control Technologies: Mexico (Decision 86/96). Report No. UNEP/OzL.Pro/ExCom/87/54 (United Nations Environment Programme, 2021).

UNEP. Report of the Eighty-Seventh Meeting of the Executive Committee. Report No. UNEP/OzL.Pro/ExCom/87/58 (United Nations Environment Programme, 2021).

Yi, L. et al. In situ observations of halogenated gases at the Shangdianzi background station and emission estimates for northern China. Environ. Sci. Technol. 57, 7217–7229 (2023).

Miller, B. R. et al. Medusa: a sample preconcentration and GC/MS detector system for in situ measurements of atmospheric trace halocarbons, hydrocarbons, and sulfur compounds. Anal. Chem. 80, 1536–1545 (2008).

Arnold, T. et al. Automated measurement of nitrogen trifluoride in ambient air. Anal. Chem. 84, 4798–4804 (2012).

Dewi, R. G. et al. in 2019 Refinement to the 2006 IPCC Guidelines for National Greenhouse Gas Inventories Ch. 3, Vol. 3 (Intergovernmental Panel of Climate Change, 2019).

Daniel, J. S. et al. in Scientific Assessment of Ozone Depletion 2022. GAW Report No. 278, Ch. 7 (World Meteorological Organization, 2022).

Mühle, J. et al. Global emissions of perfluorocyclobutane (PFC-318, c-C4F8) resulting from the use of hydrochlorofluorocarbon-22 (HCFC-22) feedstock to produce polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) and related fluorochemicals. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 22, 3371–3378 (2022).

Harnisch, J. et al. 2006 IPCC Guidelines for National Greenhouse Gas Inventories Ch. 3, Vol. 3 (Intergovernmental Panel of Climate Change, 2006).

Murphy, P. M., Schleinitz, H. M. & Van Bramer, D. J. Synthesis of tetrafluoroethylene. US patent 5672784 (1997).

Mühle, J. et al. Perfluorocyclobutane (PFC-318, c-C4F8) in the global atmosphere. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 19, 10335–10359 (2019).

Burkholder, J. B. & Hodnebrog, Ø. in Scientific Assessment of Ozone Depletion 2022. GAW Report No. 278 (World Meteorological Organization, 2022).

Keller, C. A. et al. Evidence for under-reported Western European emissions of the potent greenhouse gas HFC-23. Geophys. Res. Lett. 38, L15808 (2011).

US EPA. Global Non-CO2 Greenhouse Gas Emission Projections & Mitigation Potential: 2015–2050 (United States Environmental Protection Agency, 2019).

UNEP. Decisions adopted by the Thirty-Fourth Meeting of the Parties to the Montreal Protocol on Substances that Deplete the Ozone Layer. Report No. UNEP/OzL.Pro.34/9/Add.1/Rev.1 (United Nations Environment Programme, 2022).

UNEP. Report of the Thirty-Fourth Meeting of the Parties to the Montreal Protocol on Substances that Deplete the Ozone Layer Introduction. Report No. UNEP/OzL.Pro.34/9 (United Nations Environment Programme, 2022).

Laube, J. C. et al. in Scientific Assessment of Ozone Depletion 2022. GAW Report No. 278, Ch. 1 (World Meteorological Organization, 2022).

Prinn, R. G. et al. History of chemically and radiatively important atmospheric gases from the Advanced Global Atmospheric Gases Experiment (AGAGE). Earth Syst. Sci. Data 10, 985–1018 (2018).

Vollmer, M. K., Reimann, S., Hill, M. & Brunner, D. First observations of the fourth generation synthetic halocarbons HFC-1234yf, HFC-1234ze(E), and HCFC-1233zd(E) in the atmosphere. Environ. Sci. Technol. 49, 2703–2708 (2015).

Jones, A., Thomson, D., Hort, M. & Devenish, B. The U.K. Met Office’s Next-Generation Atmospheric Dispersion Model, NAME III. In Air Pollution Modeling and Its Application XVII (eds Borrego, C. & Norman, A. L.) 580–589 (Springer, 2007).

Acknowledgements

Support for the measurement campaign at the Cabauw tall tower and for the tracer experiment was provided by staff from Empa, TNO and the University of Bristol. The Royal Netherlands Meteorological Institute (KNMI) hosted the measurement campaign at the Cabauw tall tower and provided meteorological observations. The industrial production company at Dordrecht approved and facilitated the tracer experiment on their premises and provided background information on internal production processes. The Dienst Centraal Milieubeheer Rijnmond (DCMR) permitted the release of the tracer. The UK Met Office provided daily plume forecasts. The Swiss Federal Institute of Metrology (METAS) supported the MFC calibrations for HFC-161. The research of Empa was funded by the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF) (grant no. 200020_175921). Funding for TNO was provided by the Ministry of Economic Affairs and Climate Policy for the maintenance of greenhouse gas measurement systems at the Cabauw tower in 2022.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

D.R., M.K.V., A.F. and P.v.d.B. made the measurements. A.F., P.v.d.B. and A.H. provided campaign support. D.R., S.H., M.K.V. and S.R. processed the data. M.K.V., D.R., S.R., S.H., A.F., A.H. and K.M.S. designed the experiment. R.Z. and L.E. provided guidance on the paper structure and review. D.R., M.K.V., S.H. and S.R. wrote the paper with contributions from all the co-authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature thanks Nick Campbell, Deborah Ottinger and Guus Velders for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data figures and tables

Extended Data Fig. 1 Tracer ratio interspecies correlation.

Scatterplot between the dry-air mole fractions of the target substances (y-axis) and the dry-air mole fractions per yearly emissions of the tracer HFC-161 (see equation 2) (x-axis). The annual target substance emissions are determined as the slopes (m) of the linear regressions using weighted total least squares. The intercepts (k) represent the background mole fractions of the target substances. N is the total number of measurements included in the calculation, R2 is the coefficient of determination for the linear regression. The correlations are highly significant (p < 0.01). Uncertainties are given at 95 % confidence level. Uncertainties are sometimes smaller than the symbol size. For better visualization some of the largest mole fractions are omitted from the plots.

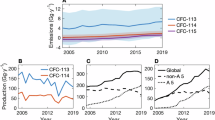

Extended Data Fig. 2 Dutch national HFC-23 and PFC-318 emissions.

Experimentally inferred HFC-23 and PFC-318 emissions (red diamonds) from an HCFC-22 and fluoropolymer production facility at Dordrecht. Uncertainties are given at 95 % confidence level. The Dutch national bottom-up inventory of HFC-23 and aggregate PFC emissions (black lines) as annually reported to the UNFCCC is shown for comparison. HFC-23 emissions of the Benelux (BLX; Belgium, the Netherlands, Luxembourg) countries for 2008–2010, derived top-down by Keller et al.43, are shown in purple and turquoise.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Rust, D., Vollmer, M.K., Henne, S. et al. Effective realization of abatement measures can reduce HFC-23 emissions. Nature 633, 96–100 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-024-07833-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-024-07833-y