Abstract

Oncogenic mutations that drive colorectal cancer can be present in healthy intestines for long periods without overt consequence1,2. Mutation of Apc, the most common initiating event in conventional adenomas3, activates Wnt signalling, thus conferring fitness on mutant intestinal stem cells (ISCs)4,5. Apc mutations may occur in ISCs that arise by routine self-renewal or by dedifferentiation of their progeny. Although ISCs of these different origins are fundamentally similar6,7, it is unclear whether both generate tumours equally well in uninjured intestines. It is also unknown whether cis-regulatory elements are substantively modulated upon Wnt hyperactivation or as a feature of subsequent tumours. Here we show in two mouse models that adenomas are not an obligatory outcome of Apc deletion in either ISC source, but require proximity of mutant intestinal crypts. Reduced crypt density abrogates, and aggregation of mutant colonic crypts augments, adenoma formation. Moreover, adenoma-resident ISCs open chromatin at thousands of enhancers that are inaccessible in Apc-null ISCs that are not associated with adenomas. These cis elements explain adenoma-selective gene activity and persist, with little further expansion of the repertoire, as other oncogenic mutations accumulate. Thus, cooperativity between neighbouring mutant crypts and new accessibility at specific enhancers are key steps early in intestinal tumorigenesis.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$32.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 51 print issues and online access

$199.00 per year

only $3.90 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

Sequencing data, deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) under accession numbers GSE241384 and GSE281056, are available without restriction. Sources of published data for epigenome comparisons (Fig. 4) are listed in the Methods. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

The script for Monte Carlo simulations of crypt clustering is included among the source data.

References

Thirlwell, C. et al. Clonality assessment and clonal ordering of individual neoplastic crypts shows polyclonality of colorectal adenomas. Gastroenterology 138, 1441–1454 (2010).

Lee-Six, H. et al. The landscape of somatic mutation in normal colorectal epithelial cells. Nature 574, 532–537 (2019).

Powell, S. M. et al. APC mutations occur early during colorectal tumorigenesis. Nature 359, 235–237 (1992).

Vermeulen, L. et al. Defining stem cell dynamics in models of intestinal tumor initiation. Science 342, 995–998 (2013).

Snippert, H. J., Schepers, A. G., van Es, J. H., Simons, B. D. & Clevers, H. Biased competition between Lgr5 intestinal stem cells driven by oncogenic mutation induces clonal expansion. EMBO Rep. 15, 62–69 (2014).

de Sousa e Melo, F. & de Sauvage, F. J. Cellular plasticity in intestinal homeostasis and disease. Cell Stem Cell 24, 54–64 (2019).

Singh, P. N. P., Madha, S., Leiter, A. B. & Shivdasani, R. A. Cell and chromatin transitions in intestinal stem cell regeneration. Genes Dev. 36, 684–698 (2022).

van de Wetering, M. et al. The β-catenin/TCF-4 complex imposes a crypt progenitor phenotype on colorectal cancer cells. Cell 111, 241–250 (2002).

Su, L. K. et al. Multiple intestinal neoplasia caused by a mutation in the murine homolog of the APC gene. Science 256, 668–670 (1992).

Sparks, A. B., Morin, P. J., Vogelstein, B. & Kinzler, K. W. Mutational analysis of the APC/β-catenin/Tcf pathway in colorectal cancer. Cancer Res. 58, 1130–1134 (1998).

Chen, B. et al. Differential pre-malignant programs and microenvironment chart distinct paths to malignancy in human colorectal polyps. Cell 184, 6262–6280 e6226 (2021).

Sansom, O. J. et al. Loss of Apc in vivo immediately perturbs Wnt signaling, differentiation, and migration. Genes Dev. 18, 1385–1390 (2004).

Fischer, J. M., Schepers, A. G., Clevers, H., Shibata, D. & Liskay, R. M. Occult progression by Apc-deficient intestinal crypts as a target for chemoprevention. Carcinogenesis 35, 237–246 (2014).

Nicholson, A. M. et al. Fixation and spread of somatic mutations in adult human colonic epithelium. Cell Stem Cell 22, 909–918 (2018).

Flanagan, D. J. et al. NOTUM from Apc-mutant cells biases clonal competition to initiate cancer. Nature 594, 430–435 (2021).

van Neerven, S. M. et al. Apc-mutant cells act as supercompetitors in intestinal tumour initiation. Nature 594, 436–441 (2021).

Yum, M. K. et al. Tracing oncogene-driven remodelling of the intestinal stem cell niche. Nature 594, 442–447 (2021).

Barker, N. et al. Identification of stem cells in small intestine and colon by marker gene Lgr5. Nature 449, 1003–1007 (2007).

Lopez-Garcia, C., Klein, A. M., Simons, B. D. & Winton, D. J. Intestinal stem cell replacement follows a pattern of neutral drift. Science 330, 822–825 (2010).

Snippert, H. J. et al. Intestinal crypt homeostasis results from neutral competition between symmetrically dividing Lgr5 stem cells. Cell 143, 134–144 (2010).

Ritsma, L. et al. Intestinal crypt homeostasis revealed at single-stem-cell level by in vivo live imaging. Nature 507, 362–365 (2014).

Schepers, A. G. et al. Lineage tracing reveals Lgr5+ stem cell activity in mouse intestinal adenomas. Science 337, 730–735 (2012).

Barker, N. et al. Crypt stem cells as the cells-of-origin of intestinal cancer. Nature 457, 608–611 (2009).

Tetteh, P. W. et al. Replacement of lost Lgr5-positive stem cells through plasticity of their enterocyte-lineage daughters. Cell Stem Cell 18, 203–213 (2016).

Tetteh, P. W. et al. Generation of an inducible colon-specific Cre enzyme mouse line for colon cancer research. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 113, 11859–11864 (2016).

Azkanaz, M. et al. Retrograde movements determine effective stem cell numbers in the intestine. Nature 607, 548–554 (2022).

van Es, J. H. et al. Dll1+ secretory progenitor cells revert to stem cells upon crypt damage. Nat. Cell Biol. 14, 1099–1104 (2012).

Tomic, G. et al. Phospho-regulation of ATOH1 Is required for plasticity of secretory progenitors and tissue regeneration. Cell Stem Cell 23, 436–443 e437 (2018).

Yu, S. et al. Paneth cell multipotency induced by Notch activation following injury. Cell Stem Cell 23, 46–59 (2018).

Jones, J. C. et al. Cellular plasticity of Defa4Cre-expressing Paneth cells in response to Notch activation and intestinal injury. Cell. Mol. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 7, 533–554 (2019).

Capdevila, C. et al. Time-resolved fate mapping identifies the intestinal upper crypt zone as an origin of Lgr5+ crypt base columnar cells. Cell 187, 3039–3055.e3014 (2024).

Schwitalla, S. et al. Intestinal tumorigenesis initiated by dedifferentiation and acquisition of stem-cell-like properties. Cell 152, 25–38 (2013).

Verhagen, M. P. et al. Non-stem cell lineages as an alternative origin of intestinal tumorigenesis in the context of inflammation. Nat. Genet. 56, 1456–1467 (2024).

Westphalen, C. B. et al. Long-lived intestinal tuft cells serve as colon cancer-initiating cells. J. Clin. Invest. 124, 1283–1295 (2014).

Shroyer, N. F. et al. Intestine-specific ablation of mouse atonal homolog 1 (Math1) reveals a role in cellular homeostasis. Gastroenterology 132, 2478–2488 (2007).

Fujiyama, T. et al. Inhibitory and excitatory subtypes of cochlear nucleus neurons are defined by distinct bHLH transcription factors, Ptf1a and Atoh1. Development 136, 2049–2058 (2009).

Madisen, L. et al. A robust and high-throughput Cre reporting and characterization system for the whole mouse brain. Nat. Neurosci. 13, 133–140 (2010).

Tian, H. et al. A reserve stem cell population in small intestine renders Lgr5-positive cells dispensable. Nature 478, 255–259 (2011).

Du, Y. C. et al. Induction and down-regulation of Sox17 and its possible roles during the course of gastrointestinal tumorigenesis. Gastroenterology 137, 1346–1357 (2009).

Sato, T. et al. Single Lgr5 stem cells build crypt–villus structures in vitro without a mesenchymal niche. Nature 459, 262–265 (2009).

Fearon, E. R., Hamilton, S. R. & Vogelstein, B. Clonal analysis of human colorectal tumors. Science 238, 193–197 (1987).

Novelli, M. R. et al. Polyclonal origin of colonic adenomas in an XO/XY patient with FAP. Science 272, 1187–1190 (1996).

Thliveris, A. T. et al. Polyclonality of familial murine adenomas: analyses of mouse chimeras with low tumor multiplicity suggest short-range interactions. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 102, 6960–6965 (2005).

Merritt, A. J., Gould, K. A. & Dove, W. F. Polyclonal structure of intestinal adenomas in ApcMin/+ mice with concomitant loss of Apc+ from all tumor lineages. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 94, 13927–13931 (1997).

Feng, Y. et al. Sox9 induction, ectopic Paneth cells, and mitotic spindle axis defects in mouse colon adenomatous epithelium arising from conditional biallelic Apc inactivation. Am. J. Pathol. 183, 493–503 (2013).

Buenrostro, J. D., Giresi, P. G., Zaba, L. C., Chang, H. Y. & Greenleaf, W. J. Transposition of native chromatin for fast and sensitive epigenomic profiling of open chromatin, DNA-binding proteins and nucleosome position. Nat. Methods 10, 1213–1218 (2013).

Stadler, M. B. et al. DNA-binding factors shape the mouse methylome at distal regulatory regions. Nature 480, 490–495 (2011).

Mo, A. et al. Epigenomic signatures of neuronal diversity in the mammalian brain. Neuron 86, 1369–1384 (2015).

Cadigan, K. M. & Waterman, M. L. TCF/LEFs and Wnt signaling in the nucleus. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 4, a007906 (2012).

Dow, L. E. et al. Apc restoration promotes cellular differentiation and reestablishes crypt homeostasis in colorectal cancer. Cell 161, 1539–1552 (2015).

de Sousa e Melo, F. et al. A distinct role for Lgr5+ stem cells in primary and metastatic colon cancer. Nature 543, 676–680 (2017).

Drost, J. et al. Sequential cancer mutations in cultured human intestinal stem cells. Nature 521, 43–47 (2015).

Garcia, S. B., Park, H. S., Novelli, M. & Wright, N. A. Field cancerization, clonality, and epithelial stem cells: the spread of mutated clones in epithelial sheets. J. Pathol. 187, 61–81 (1999).

Islam, M. et al. Temporal recording of mammalian development and precancer. Nature 634, 1187–1195 (2024).

Lu, Z. et al. Polyclonal-to-monoclonal transition in colorectal precancerous evolution. Nature 636, 233–240 (2024).

Sadien, I. D. et al. Polyclonality overcomes fitness barriers in Apc-driven tumorigenesis. Nature 634, 1196–1203 (2024).

Olpe, C. et al. A diffusion-like process accommodates new crypts during clonal expansion in human colonic epithelium. Gastroenterology 161, 548–559 (2021).

Wasan, H. S. et al. APC in the regulation of intestinal crypt fission. J. Pathol. 185, 246–255 (1998).

McCarthy, N., Kraiczy, J. & Shivdasani, R. A. Cellular and molecular architecture of the intestinal stem cell niche. Nat. Cell Biol. 22, 1033–1041 (2020).

Kobayashi, H. et al. Cancer-associated fibroblasts in gastrointestinal cancer. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 16, 282–295 (2019).

Colnot, S. et al. Colorectal cancers in a new mouse model of familial adenomatous polyposis: influence of genetic and environmental modifiers. Lab. Invest. 84, 1619–1630 (2004).

Jackson, E. L. et al. Analysis of lung tumor initiation and progression using conditional expression of oncogenic K-ras. Genes Dev. 15, 3243–3248 (2001).

Yang, X., Li, C., Herrera, P. L. & Deng, C. X. Generation of Smad4/Dpc4 conditional knockout mice. Genesis 32, 80–81 (2002).

Marino, S., Vooijs, M., van Der Gulden, H., Jonkers, J. & Berns, A. Induction of medulloblastomas in p53-null mutant mice by somatic inactivation of Rb in the external granular layer cells of the cerebellum. Genes Dev. 14, 994–1004 (2000).

Schindelin, J. et al. Fiji: an open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat. Methods 9, 676–682 (2012).

Corces, M. R. et al. An improved ATAC-seq protocol reduces background and enables interrogation of frozen tissues. Nat. Methods 14, 959–962 (2017).

Wang, F. et al. RNAscope: a novel in situ RNA analysis platform for formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissues. J. Mol. Diagn. 14, 22–29 (2012).

Manieri, E. et al. Role of PDGFRA+ cells and a CD55+ PDGFRALo fraction in the gastric mesenchymal niche. Nat. Commun. 14, 7978 (2023).

Cornwell, M. et al. VIPER: visualization pipeline for RNA-seq, a Snakemake workflow for efficient and complete RNA-seq analysis. BMC Bioinformatics 19, 135 (2018).

Dobin, A. et al. STAR: ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics 29, 15–21 (2013).

Love, M. I., Huber, W. & Anders, S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 15, 550 (2014).

Kolde, R. Pheatmap: pretty heatmaps. Version 1.0.12 https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/pheatmap/index.html (2012).

Langmead, B. & Salzberg, S. L. Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat. Methods 9, 357–359 (2012).

Zhang, Y. et al. Model-based analysis of ChIP–seq (MACS). Genome Biol. 9, R137 (2008).

Quinlan, A. R. & Hall, I. M. BEDTools: a flexible suite of utilities for comparing genomic features. Bioinformatics 26, 841–842 (2010).

Ramirez, F., Dundar, F., Diehl, S., Gruning, B. A. & Manke, T. deepTools: a flexible platform for exploring deep-sequencing data. Nucleic Acids Res. 42, W187–W191 (2014).

Lopez-Delisle, L. et al. pyGenomeTracks: reproducible plots for multivariate genomic datasets. Bioinformatics 37, 422–423 (2021).

Krueger, F. & Andrews, S. R. Bismark: a flexible aligner and methylation caller for bisulfite-seq applications. Bioinformatics 27, 1571–1572 (2011).

Wang, S. et al. Target analysis by integration of transcriptome and ChIP–seq data with BETA. Nat. Protoc. 8, 2502–2515 (2013).

Kim, T. H. et al. Broadly permissive intestinal chromatin underlies lateral inhibition and cell plasticity. Nature 506, 511–515 (2014).

Kim, C. K. et al. Kruppel-like factor 5 regulates stemness, lineage specification, and regeneration of intestinal epithelial stem cells. Cell. Mol. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 9, 587–609 (2020).

Sheaffer, K. L. et al. DNA methylation is required for the control of stem cell differentiation in the small intestine. Genes Dev. 28, 652–664 (2014).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Claudia Adams Barr programme in basic research at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, NIH grants R01DK081113 and R01 DK082889 (R.A.S.), and generous gifts from the Lind family. The authors thank J. Kraiczy and F. de Sousa e Melo for helpful discussions, and flow cytometry and organoid facilities at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute and Harvard Digestive Disease Center (P30DK034854).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.G., H.S. and R.A.S. conceived and designed the study. L.G. (Figs. 1a–h, 2a–c,e–g,i, 3a–f,h,i and 4a–e and Extended Data Figs. 1e,f, 2a,b,d,e, 3a,e,g, 4, 5, 6b–e and 8b–d), H.S. (Figs. 1f,g, 2b and 4b,d and Extended Data Fig. 8b–d), G.T. (Figs. 1f,g and 4d and Extended Data Figs. 2g, 3a, 6a and 8a), K.B. (Figs. 1i, 2d and 3g and Extended Data Figs. 2c,f,g, 3b,d,g and 8a), K.M. (Extended Data Fig. 1a,b), S.B. (Extended Data Fig. 1a–d) and U.J. (Figs. 1f,g and 4b) acquired and analysed data. L.G. (Figs. 1f,g, 2b,f,g, 3b,h and 4b–d and Extended Data Figs. 3c,f, 4b–d, 5b,c, 6b,c, 7a,e–g and 8b–f), H.S. (Fig. 4b,c and Extended Data Figs. 3c and 7a), S.B. (Extended Data Fig. 1c,d) and U.J. (Fig. 4b) performed computational analyses. S.M. supported all computational analyses. A.M. and F.J.d.S. generated the mutant organoid series (Extended Data Fig. 8d). M.H. provided Atoh1creERT2 mice. L.G. and R.A.S. wrote the manuscript, with input and approval from all authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature thanks James DeGregori, Richard Halberg and Simon Leedham for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data figures and tables

Extended Data Fig. 1 Atoh1Cre(ER) (Sec-Cre) mice capture routine Sec dedifferentiation into conventional homeostatic Lgr5+ ISCs.

a, Crypt-villus units from a representative Sec-Cre;R26RTom (Apc+/+) ileum 1 day PCI (N = 8 mice), showing labelled villus Sec and crypt base Paneth cells. Ten days PCI, nearly every villus carried scattered goblet cells and strips of consecutive tdTom+ enterocytes, which represent the progeny of dedifferentiated Atoh1Cre labelled ISCs competing neutrally with unlabelled ISCs (N = 3 mice). Three weeks PCI, tdTom label persisted only in long-lived Paneth cells and occasional whole crypt-villus units (N = 5 mice), reflecting clonal fixation of dedifferentiated Atoh1Cre-marked ISCs. Scale bars 50 μm. Created with BioRender.com. b, Labelled clonal ribbons were present 100 days PCI, indicating that dedifferentiated and clonally fixed ISCs are long-lived. N = 3 mice. Scale bars: left 1 mm, right 50 μm. c-d, Single-cell RNA analysis of ileal Sec-Cre;R26RTom crypt cells captured by tdTom flow cytometry 0.5 and 1.5 days (combined) PCI, showing a substantial fraction of tdTom+ cells that uniquely express classic ISC markers: Lgr5, Axin2, Olfm4, and others shared with replicating Atoh1+ Sec progenitors (Sec-pro): Top2a and Mki67. The findings confirm that Sec-cell dedifferentiation is a routine homeostatic event. Ent-pro, enterocyte progenitors; Gob/Pan (GP), goblet/Paneth precursors; EE, enteroendocrine. e, Higher labelling of whole crypts in ISC-Cre (N = 4 mice) than in Sec-Cre (N = 6 mice) Apc+/+ (WT) ilea. Bars, mean +SD; unpaired t test with Welch’s correction, one-tailed). f, Adenomas carpeted ISC-Cre duodenum 3 weeks PCI, necessitating euthanasia (N = 12 mice). Scale bar 1 mm.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Different tumour loads in ISC-Cre and Sec-Cre ApcFl/Fl ileum.

a, Distributions of clonal events in ISC-Cre and Sec-Cre Apc+/+ and ApcFl/Fl ilea. N, mouse numbers. P values from comparisons between ApcFl/Fl ilea in ISC-Cre vs. Sec-Cre derived using unpaired t test with Welch’s correction (one-tailed). b, Photomicrograph of an Apc−/− Sec-Cre ileum 16 weeks PI, showing a single diminutive adenoma (dashed rectangle, magnified in inset). Scale bar 1 mm, inset 100 µm. c, ISC-Cre Apc−/− ileal adenoma showing that S-phase (EdU+) cells are not confined to crypts, as in neighboring Apc+/+ tissue, but present throughout the tumour. N = 4 mice, scale bar 50 μm. d, Illustrative tdTomato- microadenoma (dashed oval, 1 example from N = 2 mice) in Sec-Cre ileum, reflecting Cre-induced recombination at the Apc but occasionally not at the Rosa26 locus. Bar 50 μm. e, PCR genotyping of genomic DNA for Apc exon 14 shows the excised (floxed, 240 bp) product in FACS-purified ISCs (Tom+ cells) from ISC-Cre or Sec-Cre mice, but not in Tom- cells. A larger non-specific PCR product is amplified in all samples. N = 2 independent isolates. Whole gel is shown. f, Axin2 RNA in situ hybridization shows expression as a marker of active Wnt signaling in proliferative normal crypt cells and elevated levels in scattered cystic structures (arrows) in Sec-Cre;Apcfl/fl ileum. N = 3 intestines. Scale bar 1 mm; boxed area is magnified below, scale bar 50 μm. g, PCR genotyping of genomic DNA for KrasG12D (top, N = 3 mice) and null Smad4 (right, N = 2 mice) alleles verifies Cre-mediated recombination in FACS-purified ISCs (Tom+ cells) but not in DNA extracted from toes (top N = 3 mice, bottom N = 2 mice), which lack Cre recombinase. Source gels shown in Supplementary Fig. 1.

Extended Data Fig. 3 Gene deregulation in Apc-null ISCs and organoids.

a, Representative FACS plots for purification of Apc−/− ISCs (GFP+ Tom+) from ISC-Cre;R26RTom mice (left, n > 10) and from Sec-Cre;R26RTom mice that also carry the Lgr5Dtr-Gfp allele44 for fluorescent ISC marking (right, n > 10). ISCs reflecting dedifferentiation of Atoh1Cre labelled Sec cells represent 1.7% of viable cells in Sec-Cre mice 6 weeks PCI. Supplementary Fig. 2 shows the FACS gating strategy. b, Apc-null adenomas in ISC-Cre contain a high proportion of GFP+ (Lgr5+) ISCs, extending well beyond the crypt base. N = 8 mice. Left, merged fluorescent signals; right, isolated GFP (Lgr5) signal. Scale bar 50 μm. c, Aberrant expression of 3,286 genes (RNA-seq, DESeq2 analysis, two-tailed Wald test corrected for multiple comparisons, q < 0.01, log2 fold-change >2, base mean >20 counts) in Apc−/− ISCs isolated from ISC-Cre mice compared to Apc+/+ (WT, from mice lacking Cre) ISCs, both isolated 14 days PCI. d, Additional example of Notum expression (RNA in situ hybridization) in Sec-Cre ileal clones (N = 4 mice, scale bar 50 μm). e, Wild-type (Apc+/+) organoids are budding structures, distinct from the spheroidal morphology observed in Apc-null organoids. N = 5 independent cultures, scale bar 1 mm. f, Aberrant gene expression in Apc−/− organoids in vitro overlaps with genes dysregulated in Apc−/− ISCs isolated from ISC-Cre mice. Table shows examples of genes dysregulated (average DESeq read counts from N = 2 mice each) in ISCs from ISC-Cre mice and their relative expression in ISCs isolated from WT mice, Apc−/− ISCs isolated from Sec-Cre mice (in vivo), and organoids cultured from each source of small intestine crypts (N = 2 independent cultures from each). g, RNA in situ hybridization shows Notum (top, N = 2 mice) and Spock2 (bottom, N = 2 mice) expression predominantly in ISC-Cre adenomas. Scale bars 50 μm; dashed lines demarcate crypt bottoms. h, Context-dependent consequences of Apc loss. In gene activity and absence of adenomatous features, ISCs from Sec-Cre behave like WT ISCs in vivo but their expansion in organoid medium lacking RSPO phenocopies their ISC-Cre counterparts. Created with BioRender.com.

Extended Data Fig. 4 Monte Carlo simulations of crypt clustering.

a, Variegated Lgr5Cre expression in ISC-Cre mice and sporadic dedifferentiation in ISC-Cre mice result in areas with variably dense (top, 5 days PCI, N = 6 mice) and sparse (bottom, N = 15 mice) tdTom labelling, respectively. Scale bars 50 μm. b, Top: the relation between crypt clustering (y-axis, values +SD) and basal rates of crypt labelling (x-axis) is non-linear. Bottom: derivatives of the clustering rates. The largest change in clustering rate occurs between the labelling rates observed in ISC-Cre and Sec-Cre ileum. c, Simulation of crypt clustering in silico. Using normal distributions fit to the observed rates of crypt labelling, sequential crypts with randomly selected cells were represented by vectors, given the prescribed rate of labelling, and simulated in silico. Distributions of clustered crypts were generated from 100,000 iterations for each dataset. d, The cluster distribution of Sec-Cre crypts (top) fell at the low end of the range expected from random labelling. In contrast, ISC-Cre mouse ilea (bottom) showed more clustering than predicted from random basal crypt labelling, as expected from the known patchiness of variegated Lgr5Cre expression. Dark grey: 5th to 95th percentile range, light grey: maximum range for the simulated data. Cumulative frequencies displayed together for comparison in Fig. 2f. e, Whole mount fluorescence micrograph of the largest crypt cluster detected in a Sec-Cre ileum (14 weeks PCI, example from N = 4) and showing adenomatous features: extension beyond the tissue plane and effaced crypt boundaries. Scattered isolated crypts appear on the periphery. Whole-mount fluorescence image from ApcFl/Fl ISC-Cre ileum 16 days PCI shows an adenoma (dashed yellow structure: extra-planar growth, fused dysmorphic crypts) among variably sized patches of untransformed Apc-null crypts with distinct borders. N = 4 mice, scale bars 1 mm.

Extended Data Fig. 5 Perturbations of crypt clustering in Sec-Cre mice.

a, Whole-mount images of representative ISC-Cre ilea 5 days and 15 days PCI demonstrate dense, patchy labelling correlated with adenomas (15 days PCI), compared to diffusely scattered singletons observed in Sec-Cre as late as 14 weeks PCI. Bars 1 cm. Below, tdTom fluorescence signals in ISC-Cre whole mounts (5 days PCI, N = 4 ilea) are greatest in the distal 2 cm, correlating with tumour size and abundance at euthanasia (2-3 weeks PCI, N = 4 ilea). b, Increased rates of clonal crypt marking in Sec-Cre;ApcFl/Fl mice with 12 injections of Tam or by ablating Lgr5DTR-Gfp ISCs with Diphtheria toxin (DT), hence increasing Sec cell dedifferentiation. N, mouse numbers; first two columns repeated from Fig. 1d; unpaired t test with Welch’s correction, one-tailed. c, Upon elevation of basal crypt labelling with 12 doses of Tam (top) or DT treatment (bottom), Monte Carlo simulations showed more doublets than expected from random crypt distributions (dark dots in right graph), but larger clusters remained rare. Cumulative frequencies displayed together for comparisons in Fig. 3b; dark grey shading: 5th to 95th percentile range, light grey: maximum range for simulated data. d, High TdTom labelling in Sec-Cre colon, owing to large number of native Sec cells available to dedifferentiate. N = 6 colons, scale bar 1 mm. e, High adenoma burden after 12X Tam in a representative Sec-Cre;ApcFl/Fl colon from N = 8 mice. Scale bar 1 mm, boxed area magnified below (scale bar 150 μm).

Extended Data Fig. 6 Perturbation of crypt clustering in ISC-Cre mice.

a, PCR genotyping of genomic DNA for Apc exon 14 shows the excised product (240 bp) in FACS-purified ISCs (Tom+ cells) from ISC-Cre mice treated with 0.1 mg Tam (N = 2 mice) but not in ISCs purified from animals that did not receive Tam (N = 2 mice). Purified Tom- and Tom+ crypt cell fractions from mice treated with 1 mg Tam (Extended Data Fig. 2g) serve as negative and positive controls. Whole gel is shown; a larger non-specific PCR product is amplified in all samples. b, In situ hybridization revealed Notum expression in clonal structures in ISC-Cre;Apcfl/fl ileum after 2 doses of 0.1 mg Tam (N = 2 mice). Top: low magnification, bottom (2 images): high magnification; all scale bars 50 μm. c, Monte Carlo simulations revealed high clustering after ISC-Cre mice were treated with 0.1 mg Tam, as expected from the underlying patchy variegation, but cluster sizes were substantially reduced compared to mice treated with 1 mg Tam. Cumulative frequencies compared with others in Fig. 3g; dark grey: 5th to 95th percentile range, light grey: maximum range for simulated data. Note different y-axis ranges for 1 mg and 0.1 mg treatments; circled dots: measured clustering frequencies. d, Sparse crypt labelling detected in ISC-Cre ApcFl/Fl ileum whole mounts 5 days PCI with 0.1 mg Tam. N = 3 mice, scale bar 1 cm. e, Whole ISC-Cre;ApcFl/Fl ileum 8 weeks (N = 4 mice) and 23 weeks (N = 2 mice) PCI after 0.1 mg Tam, showing small discrete adenomas (dashed ovals) in one of the latter ilea. Scale bars 1 cm.

Extended Data Fig. 7 Altered enhancer accessibility in adenoma-resident Apc-null ISCs.

a, Aberrant accessibility at 7,298 enhancers (DESeq2 analysis, log2 fold-change >2, two-tailed Wald test corrected for multiple comparisons, q < 0.01) in Apc−/− duodenal ISCs from ISC-Cre mice, compared to Apc+/+ (WT, from mice lacking Cre) ISCs, both isolated 14 days PCI. N = 2 mice each. b, DNA at enhancers newly accessible in ISCs from adenoma-bearing ISC-Cre mice are hypomethylated (range 0% to 100% methylation in sites containing >5 CpGs) relative to the same sites in Apc+/+ ISCs. Signals representing the full spectrum of DNA methylation are shown for comparison: at 5,000 arbitrary active H3K27ac+ enhancers (unmethylated in ISCs), at all CpGs (largely methylated), and at 5,000 neuronal enhancers37 (unmethylated in neuronal cells but methylated in WT and Apc−/− ISCs). c, DNA sequence motifs appreciably enriched among enhancers newly accessible in Apc−/− ISCs match transcription factors from the AP-1, TCF/LEF and FOX0 families. P values derived using the Fisher Exact test (one-tailed, corrected for multiple comparisons). d, Additional representative PyGenome tracks illustrate newly accessible enhancers (asterisks) in a locus (Spock2) with elevated RNA expression in Apc−/− ISCs. e, Top: differential analysis of enhancers in Apc−/− ileal ISCs from ISC-Cre mice treated with 1 mg or 0.1 mg Tam, showing differences similar to those across ~100,000 called ATAC-seq peaks (DEseq2, two-tailed Wald test corrected for multiple comparisons, q < 0.01, log2 fold-change ≥2) between WT and adenoma-resident duodenal ISCs. Bottom, alternative display of volcano plot shown in panel a. f, Pearson correlations among called peaks in ATAC-seq analysis of WT or adenoma-resident Apc−/− duodenal ISCs and of WT or Apc−/− ileal ISCs from Sec-Cre mice and from ISC-Cre mice treated with 1 mg or 0.1 mg Tam. Black boxes demarcate like samples: WT ISCs (bottom left, showing regional differences); adenoma-resident ISCs (top right, duodenal and ileal); ISCs not associated with adenomas (center, Sec-Cre mice treated with 1 mg Tam and ISC-Cre mice treated with 0.1 mg Tam). g, Differential analysis of enhancers in Apc−/− ISCs from Sec-Cre mice treated with 1 mg Tam and from ISC-Cre mice treated with 0.1 mg Tam, showing few differences across ~100,000 called ATAC-seq peaks, in contrast to the modulated chromatin access in adenoma-resident Apc−/− ISCs from ISC-Cre mice (1 mg Tam, panel e). h, Additional PyGenome tracks from ATAC-seq samples represented in Fig. 4d, showing sites selectively accessible (shaded boxes) in adenoma-resident ISCs.

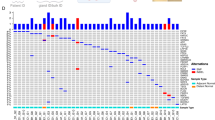

Extended Data Fig. 8 Lack of appreciable additional enhancer accessibility when oncogenic mutations are superimposed on Apc-null ISCs.

a, PCR genotyping of genomic DNA for Trp53 deletion reveals the 612-bp product (verified by DNA sequence) expected from Cre-mediated recombination in FACS-purified ISCs (Tom+ cells, N = 3 independent isolates) but not in DNA extracted from toes (N = 3 mice), which lack Cre recombinase. A non-specific PCR product (uninterpretable DNA sequence) was amplified in all samples. Source gel shown in Supplementary Fig. 1. b, Minimal expansion of the enhancer repertoire (519 additional accessible sites, log2 fold-change ≥2, DESeq2, two-tailed Wald test corrected for multiple comparisons, q <0.01), in adenoma-associated Apc−/− ISCs upon addition of KrasG12D mutation (N = 4 mice) and no further expansion upon Trp53 loss (N = 2 mice) in vivo. Two samples shown for each genotype. c, Principal component (PC) analysis of open chromatin (MACS2 called peaks) in WT (N = 4 independent organoid cultures), Apc−/− (A, N = 3 cultures), Apc−/−;KrasG12D (AK, N = 4 cultures), Apc−/−;KrasG12D;Trp53−/− (AKP, N = 2 cultures), and Apc−/−;KrasG12D;Trp53−/−;Smad4−/− (AKPS, N = 3 cultures) intestinal organoids. The largest distinction (PC1) is between WT and all Apc-null organoids. d, K-means clustering (k = 3) of 7,574 sites with objectively differential chromatin access in the mutational series compared to WT ISCs. All mutant organoids gave consistent signals across strong (cluster 1: n = 701) and moderate (cluster 2: n = 2,376) sites. The volcano plot shows that 4,497 sites (cluster 3) with ostensibly enriched access in AKPS organoids fail stringent thresholds for significance (two-tailed Wald test corrected for multiple comparisons). Control sites are 4,000 arbitrary enhancers accessible in all organoids, including WT. e, Significant overlap between enhancers differentially accessible in Apc-null ISCs in vivo and Apc−/− organoid cultures. Sites are clustered by whether peaks were called only in vivo, only in organoids, or in both. At sites called only in one, signals are evident in the other, but not in WT ISCs or organoids. Drawings in b–e were created with BioRender.com. f, PyGenome tracks for ATAC-seq signals at the Sox17 locus in Apc−/− ISCs isolated from ISC-Cre crypts in vivo and in organoids cultured from WT or Apc−/− intestinal crypts. Boxed areas are magnified below to highlight chromatin access in those locations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

This file contains Supplementary Figs. 1 and 2 and Suppleemntary Tables 1. Supplementary Fig. 1: Uncropped gels from genotyping analyses shown in extended data. Supplementary Fig. 2: FACS gating strategy to sort GFP+ tdTom+ intestinal stem cells. Supplementary Table 1: Summary of all statistical tests used in the study.

Supplementary Data

Scripts for Monte Carlo simulations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Gaynor, L., Singh, H., Tie, G. et al. Crypt density and recruited enhancers underlie intestinal tumour initiation. Nature 640, 231–239 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-024-08573-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-024-08573-9

This article is cited by

-

Decay of driver mutations shapes the landscape of intestinal transformation

Nature (2026)

-

Biological roles of enhancer RNA m6A modification and its implications in cancer

Cell Communication and Signaling (2025)

-

Early mutational events and clonal dynamics in normal crypts: implications for colorectal tumorigenesis

Human Genomics (2025)

-

Defining the mucosal ecosystem: epithelial–mesenchymal interdependence in gastrointestinal health and disease

Nature Reviews Gastroenterology & Hepatology (2025)

-

Redefining familial adenomatous polyposis: competition, cooperation, and the path to monoclonality

Familial Cancer (2025)