Abstract

Will it ever be possible to sue anyone for damaging the climate? Twenty years after this question was first posed, we argue that the scientific case for climate liability is closed. Here we detail the scientific and legal implications of an ‘end-to-end’ attribution that links fossil fuel producers to specific damages from warming. Using scope 1 and 3 emissions data from major fossil fuel companies, peer-reviewed attribution methods and advances in empirical climate economics, we illustrate the trillions in economic losses attributable to the extreme heat caused by emissions from individual companies. Emissions linked to Chevron, the highest-emitting investor-owned company in our data, for example, very likely caused between US $791 billion and $3.6 trillion in heat-related losses over the period 1991–2020, disproportionately harming the tropical regions least culpable for warming. More broadly, we outline a transparent, reproducible and flexible framework that formalizes how end-to-end attribution could inform litigation by assessing whose emissions are responsible and for which harms. Drawing quantitative linkages between individual emitters and particularized harms is now feasible, making science no longer an obstacle to the justiciability of climate liability claims.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$32.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 51 print issues and online access

$199.00 per year

only $3.90 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

All data that support the findings of this study are available through IEEE DataPort at https://doi.org/10.21227/w3fm-w720.

Code availability

All computer code that supports the findings of this study are available through IEEE DataPort at https://doi.org/10.21227/w3fm-w720.

References

Allen, M. Liability for climate change. Nature 421, 891–892 (2003). This paper first proposed a scientific basis for claims for legal liability resulting from climate impacts.

Kysar, D. A. What climate change can do about tort law. Environ. Law 41, 1–71 (2011).

Cranor, C. F. The science veil over tort law policy: how should scientific evidence be utilized in toxic tort law? Law Philos. 24, 139–210 (2005).

Seneviratne, S. I. et al. in Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (eds Masson-Delmotte, V. et al.) 1513–1766 (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2021).

Swain, D. L., Singh, D., Touma, D. & Diffenbaugh, N. S. Attributing extreme events to climate change: a new frontier in a warming world. One Earth 2, 522–527 (2020).

Diffenbaugh, N. S. et al. Quantifying the influence of global warming on unprecedented extreme climate events. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 114, 4881–4886 (2017).

Trenberth, K. E., Fasullo, J. T. & Shepherd, T. G. Attribution of climate extreme events. Nat. Clim. Change 5, 725–730 (2015).

Stott, P. A., Stone, D. A. & Allen, M. R. Human contribution to the European heatwave of 2003. Nature 432, 610–614 (2004). This paper was the first single-event global warming attribution study.

Otto, F. E. L., Massey, N., van Oldenborgh, G. J., Jones, R. G. & Allen, M. R. Reconciling two approaches to attribution of the 2010 Russian heat wave. Geophys. Res. Lett. 39, L04702 (2012).

Diffenbaugh, N. S., Swain, D. L. & Touma, D. Anthropogenic warming has increased drought risk in California. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 112, 3931–3936 (2015).

Williams, A. P. et al. Large contribution from anthropogenic warming to an emerging North American megadrought. Science 368, 314–318 (2020).

Pall, P. et al. Anthropogenic greenhouse gas contribution to flood risk in England and Wales in autumn 2000. Nature 470, 382–385 (2011).

Patricola, C. M. & Wehner, M. F. Anthropogenic influences on major tropical cyclone events. Nature 563, 339–346 (2018).

Risser, M. D. & Wehner, M. F. Attributable human-induced changes in the likelihood and magnitude of the observed extreme precipitation during Hurricane Harvey. Geophys. Res. Lett. 44, 12,457–12,464 (2017).

Abatzoglou, J. T. & Williams, A. P. Impact of anthropogenic climate change on wildfire across western US forests. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 113, 11770–11775 (2016).

Philip, S. et al. A protocol for probabilistic extreme event attribution analyses. Adv. Stat. Climatol. Meteorol. Oceanogr. 6, 177–203 (2020). This paper outlines the standard procedure for event attribution used by the World Weather Attribution group, reflecting the scientific consensus on extreme event attribution.

Reed, K. A. & Wehner, M. F. Real-time attribution of the influence of climate change on extreme weather events: a storyline case study of Hurricane Ian rainfall. Environ. Res. Clim. 2, 043001 (2023).

Reed, K., Stansfield, A., Wehner, M. & Zarzycki, C. Forecasted attribution of the human influence on Hurricane Florence. Sci. Adv. 6, eaaw9253 (2020).

Banda, M., L. Climate science in the courts: a review of U.S. and international judicial pronouncements. Environmental Law Institute https://www.eli.org/research-report/climate-science-courts-review-us-and-international-judicial-pronouncements (2020).

Wehner, M. F. & Reed, K. A. Operational extreme weather event attribution can quantify climate change loss and damages. PLOS Clim. 1, e0000013 (2022).

Daubert v. Merrell Dow Pharmaceuticals, Inc., 509 U.S. 579 (1993).

Case, L. Climate change: a new realm of tort litigation, and how to recover when the litigation heats up. Santa Clara Law Rev. 51, 265 (2011).

Marjanac, S. & Patton, L. Extreme weather event attribution science and climate change litigation: an essential step in the causal chain? J. Energy Nat. Resour. Law 36, 265–298 (2018).

Marjanac, S., Patton, L. & Thornton, J. Acts of God, human influence and litigation. Nat. Geosci. 10, 616–619 (2017).

Setzer, J. & Higham, C. Global trends in climate change litigation: 2022 snapshot. London School of Economics and Political Science https://www.lse.ac.uk/granthaminstitute/publication/global-trends-in-climate-change-litigation-2022/ (2022).

Peel, J. & Osofsky, H. M. A rights turn in climate change litigation? Transnatl Environ. Law 7, 37–67 (2018).

Tienhaara, K., Thrasher, R., Simmons, B. A. & Gallagher, K. P. Investor-state disputes threaten the global green energy transition. Science 376, 701–703 (2022).

Wentz, J. & Franta, B. Liability for public deception: linking fossil fuel disinformation to climate damages. Environ. Law Report. 52, 10995–11020 (2022).

Wasim, R. Corporate (non)disclosure of climate change information. Columbia Law Rev. 119, 1311–1354 (2019).

Wentz, J., Merner, D., Franta, B., Lehmen, A. & Frumhoff, P. C. Research priorities for climate litigation. Earths Future 11, e2022EF002928 (2023).

Olszynski, M., Mascher, S. & Doelle, M. From smokes to smokestacks: lessons from tobacco for the future of climate change liability. Georget. Environ. Law Rev. 30, 1–46 (2017).

Kaufman, J. Oklahoma v. Purdue Pharma: public nuisance in your medicine cabinet. Cardozo Law Rev. 42, 429–462 (2020).

Bouwer, K. Lessons from a distorted metaphor: the Holy Grail of climate litigation. Transnatl Environ. Law 9, 347–378 (2020).

County of Multnomah v. Exxon Mobil Corp. (2023).

City of New York v. Chevron Corp., no. 18-2188 (2019).

State of Rhode Island v. Shell Oil Products Co., LLC, no. 19-1818 (2020).

Municipalities of Puerto Rico v. Exxon Mobil Corp. (2022).

Native Village of Kivalina v. ExxonMobil Corp. (2009).

Urgenda Foundation v State of the Netherlands (2015).

Tanne, J. H. Young people in Montana win lawsuit for clean environment. BMJ 382, 1891 (2023).

Buchanan, M. The coming wave of climate legal action. Semafor https://www.semafor.com/article/02/01/2023/the-coming-wave-of-climate-legal-action (2023).

Davis, S. J. & Diffenbaugh, N. Dislocated interests and climate change. Environ. Res. Lett. 11, 061001 (2016).

Harrington, L. J. & Otto, F. E. L. Attributable damage liability in a non-linear climate. Clim. Change 153, 15–20 (2019).

Prather, M. J. et al. Tracking uncertainties in the causal chain from human activities to climate. Geophys. Res. Lett. 36, L05707 (2009).

No authors listed. Causation in environmental law: lessons from toxic torts. Harv. Law Rev. 128, 2256–2277 (2015).

Green, M. D. & Powers, Jr., W. C. Restatement of the Law Third, Torts: Liability for Physical and Emotional Harm (American Law Institute, 2010).

Grimm, D. J. Global warming and market share liability: a proposed model for allocating tort damages among CO2 producers. Colum. J. Environ. Law 32, 209 (2007).

Peñalver, E. M. Acts of God or toxic torts? Applying tort principles to the problem of climate change. Nat. Resour. J. 38, 563–601 (1998).

Lloyd, E. A. & Shepherd, T. G. Climate change attribution and legal contexts: evidence and the role of storylines. Clim. Change 167, 28 (2021).

Burke, M., Zahid, M., Diffenbaugh, N. & Hsiang, S. M. Quantifying climate change loss and damage consistent with a social cost of greenhouse gases. NBER working paper 31658. National Bureau of Economic Research https://www.nber.org/papers/w31658 (2023).

Schleussner, C.-F., Andrijevic, M., Kikstra, J., Heede, R. & Rogelj, J. Fossil fuel companies’ true balance sheets. ESS Open Archive https://doi.org/10.22541/essoar.167810526.62141909/v1 (2023).

Trudinger, C. & Enting, I. Comparison of formalisms for attributing responsibility for climate change: non-linearities in the Brazilian Proposal approach. Clim. Change 68, 67–99 (2005).

Callahan, C. W. & Mankin, J. S. National attribution of historical climate damages. Clim. Change 172, 40 (2022).

Rostron, A. Beyond market share liability: a theory of proportional share liability for nonfungible products. UCLA Law Rev. 52, 151–215 (2004).

Stuart-Smith, R. F. et al. Filling the evidentiary gap in climate litigation. Nat. Clim. Change 11, 651–655 (2021).

Holt, S. & McGrath, C. Climate change: is the common law up to the task? Auckland Univ. Law Rev. 24, 10–31 (2018).

Memorandum of Law of Chevron Corporation, ConocoPhillips, and Exxon Mobil Corporation Addressing Common Grounds in Support of their Motions to Dismiss Plaintiff’s Amended Complaint. City of New York v. BP P.L.C.; Chevron Corporation; ConocoPhillips; Exxon Mobil Corporation; and Royal Dutch Shell PLC. Case no. 18 Civ. 182 (2018).

Burger, M., Wentz, J. & Horton, R. The law and science of climate change attribution. Colum. J. Environ. Law 45, 57–240 (2020). This paper outlines the potential for attribution science to inform climate litigation, and specifically to fulfil the causation requirement for standing.

Höhne, N. et al. Contributions of individual countries’ emissions to climate change and their uncertainty. Clim. Change 106, 359–391 (2011).

Skeie, R. B. et al. Perspective has a strong effect on the calculation of historical contributions to global warming. Environ. Res. Lett. 12, 024022 (2017).

Matthews, H. D. Quantifying historical carbon and climate debts among nations. Nat. Clim. Change 6, 60–64 (2016).

Heede, R. Tracing anthropogenic carbon dioxide and methane emissions to fossil fuel and cement producers, 1854–2010. Clim. Change 122, 229–241 (2014). This paper was the first to systematically link individual fossil fuel producers to the emissions resulting from the consumption of their products.

Ekwurzel, B. et al. The rise in global atmospheric CO2, surface temperature, and sea level from emissions traced to major carbon producers. Clim. Change 144, 579–590 (2017).

Licker, R. et al. Attributing ocean acidification to major carbon producers. Environ. Res. Lett. 14, 124060 (2019).

Otto, F. E. L., Skeie, R. B., Fuglestvedt, J. S., Berntsen, T. & Allen, M. R. Assigning historic responsibility for extreme weather events. Nat. Clim. Change 7, 757–759 (2017).

Dahl, K. A. et al. Quantifying the contribution of major carbon producers to increases in vapor pressure deficit and burned area in western US and southwestern Canadian forests. Environ. Res. Lett. 18, 064011 (2023).

Beusch, L. et al. Responsibility of major emitters for country-level warming and extreme hot years. Commun. Earth Environ. 3, 7 (2022).

Wei, T. et al. Developed and developing world responsibilities for historical climate change and CO2 mitigation. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 109, 12911–12915 (2012).

Wigley, T. M. L. & Raper, S. C. B. Interpretation of high projections for global-mean warming. Science 293, 451–454 (2001).

Millar, R. J., Nicholls, Z. R., Friedlingstein, P. & Allen, M. R. A modified impulse-response representation of the global near-surface air temperature and atmospheric concentration response to carbon dioxide emissions. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 17, 7213–7228 (2017).

Smith, C. J. et al. FAIR v1.3: a simple emissions-based impulse response and carbon cycle model. Geosci. Model Dev. 11, 2273–2297 (2018).

Leach, N. J. et al. FaIRv2.0.0: a generalized impulse response model for climate uncertainty and future scenario exploration. Geosci. Model Dev. 14, 3007–3036 (2021).

Nicholls, Z. R. J. et al. Reduced Complexity Model Intercomparison Project Phase 1: introduction and evaluation of global-mean temperature response. Geosci. Model Dev. 13, 5175–5190 (2020).

Rogelj, J. et al. in Global Warming of 1.5°C. An IPCC Special Report on the impacts of global warming of 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels and related global greenhouse gas emission pathways, in the context of strengthening the global response to the threat of climate change, sustainable development, and efforts to eradicate poverty (eds Masson-Delmotte, V. et al.) 93–174 (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2018).

Lynch, C., Hartin, C., Bond-Lamberty, B. & Kravitz, B. An open-access CMIP5 pattern library for temperature and precipitation: description and methodology. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 9, 281–292 (2017).

Mitchell, T. D. Pattern scaling: an examination of the accuracy of the technique for describing future climates. Clim. Change 60, 217–242 (2003).

Tebaldi, C. & Arblaster, J. M. Pattern scaling: its strengths and limitations, and an update on the latest model simulations. Clim. Change 122, 459–471 (2014).

Seneviratne, S. I., Donat, M. G., Pitman, A. J., Knutti, R. & Wilby, R. L. Allowable CO2 emissions based on regional and impact-related climate targets. Nature 529, 477–483 (2016).

Carleton, T. A. & Hsiang, S. M. Social and economic impacts of climate. Science 353, aad9837 (2016). This review documents many of the methodological advances used in assessing the socioeconomic impacts of climate change.

Schlenker, W. & Roberts, M. J. Nonlinear temperature effects indicate severe damages to US crop yields under climate change. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 106, 15594–15598 (2009).

Carleton, T. et al. Valuing the global mortality consequences of climate change accounting for adaptation costs and benefits. Q. J. Econ. 137, 2037–2105 (2022).

Barreca, A., Clay, K., Deschenes, O., Greenstone, M. & Shapiro, J. S. Adapting to climate change: the remarkable decline in the US temperature-mortality relationship over the twentieth century. J. Political Econ. 124, 105–159 (2016).

Dell, M., Jones, B. F. & Olken, B. A. Temperature shocks and economic growth: evidence from the last half century. Am. Econ. J. Macroecon. 4, 66–95 (2012).

Burke, M., Hsiang, S. M. & Miguel, E. Global non-linear effect of temperature on economic production. Nature 527, 235–239 (2015).

Kalkuhl, M. & Wenz, L. The impact of climate conditions on economic production. Evidence from a global panel of regions. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 103, 102360 (2020).

Davenport, F. V., Burke, M. & Diffenbaugh, N. S. Contribution of historical precipitation change to US flood damages. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 118, e2017524118 (2021).

Diffenbaugh, N. S., Davenport, F. V. & Burke, M. Historical warming has increased U.S. crop insurance losses. Environ. Res. Lett. 16, 084025 (2021).

Diffenbaugh, N. S. & Burke, M. Global warming has increased global economic inequality. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 116, 9808–9813 (2019).

Callahan, C. W. & Mankin, J. S. Globally unequal effect of extreme heat on economic growth. Sci. Adv. 8, eadd3726 (2022).

Hsiang, S. et al. in Fifth National Climate Assessment (eds Crimmins, A. R. et al.) Ch. 19 (U.S. Global Change Research Program, 2023).

Lott, F. C. et al. Quantifying the contribution of an individual to making extreme weather events more likely. Environ. Res. Lett. 16, 104040 (2021).

Mitchell, D. et al. Attributing human mortality during extreme heat waves to anthropogenic climate change. Environ. Res. Lett. 11, 074006 (2016).

Frame, D. J. et al. Climate change attribution and the economic costs of extreme weather events: a study on damages from extreme rainfall and drought. Clim. Change 162, 781–797 (2020).

Frame, D. J., Wehner, M. F., Noy, I. & Rosier, S. M. The economic costs of Hurricane Harvey attributable to climate change. Clim. Change 160, 271–281 (2020).

Newman, R. & Noy, I. The global costs of extreme weather that are attributable to climate change. Nat. Commun. 14, 6103 (2023).

Perkins-Kirkpatrick, S. E. et al. On the attribution of the impacts of extreme weather events to anthropogenic climate change. Environ. Res. Lett. 17, 024009 (2022).

Brown, P. T. When the fraction of attributable risk does not inform the impact associated with anthropogenic climate change. Clim. Change 176, 115 (2023).

Allen, M. et al. Scientific challenges in the attribution of harm to human influence on climate. Univ. Pa. Law Rev. 155, 1353–1400 (2007).

Strauss, B. H. et al. Economic damages from Hurricane Sandy attributable to sea level rise caused by anthropogenic climate change. Nat. Commun. 12, 2720 (2021).

Carbon Majors database. https://carbonmajors.org/ (2024).

Forster, P. et al. in Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (eds Masson-Delmotte, V. et al.) 923–1054 (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2021).

Burke, M. & Tanutama, V. Climatic constraints on aggregate economic output. NBER working paper 25779. National Bureau of Economic Research https://www.nber.org/papers/w25779 (2019).

Kotz, M., Levermann, A. & Wenz, L. The economic commitment of climate change. Nature 628, 551–557 (2024).

Waidelich, P., Batibeniz, F., Rising, J. A., Kikstra, J. & Seneviratne, S. I. Climate damage projections beyond annual temperature. Nat. Clim. Change 14, 592–599 (2024).

Kotz, M., Levermann, A. & Wenz, L. The effect of rainfall changes on economic production. Nature 601, 223–227 (2022).

Miller, S., Chua, K., Coggins, J. & Mohtadi, H. Heat waves, climate change, and economic output. J. Eur. Econ. Assoc. 19, 2658–2694 (2021).

Gelles, D. Oregon county sues fossil fuel companies over 2021 heat dome. New York Times https://www.nytimes.com/2023/06/22/climate/oregon-lawsuit-heat-dome.html (22 June 2023).

Rahmstorf, S. & Coumou, D. Increase of extreme events in a warming world. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 108, 17905–17909 (2011).

Mishra, V., Mukherjee, S., Kumar, R. & Stone, D. A. Heat wave exposure in India in current, 1.5 °C, and 2.0 °C worlds. Environ. Res. Lett. 12, 124012 (2017).

Supran, G., Rahmstorf, S. & Oreskes, N. Assessing ExxonMobil’s global warming projections. Science 379, eabk0063 (2023).

Supran, G. & Oreskes, N. Assessing ExxonMobil’s climate change communications (1977–2014). Environ. Res. Lett. 12, 084019 (2017). This paper found that ExxonMobil systematically cast doubt on mainstream climate science in the public sphere while internally acknowledging climate change and its consequences.

Callahan, C. W. & Mankin, J. S. Persistent effect of El Niño on global economic growth. Science 380, 1064–1069 (2023).

Lloyd, E. A., Oreskes, N., Seneviratne, S. I. & Larson, E. J. Climate scientists set the bar of proof too high. Clim. Change 165, 55 (2021). This paper outlines the different burdens of proof used in science and law, arguing that scientific standards are often too strict relative to legal standards.

Editorial. It’s time to talk about ditching statistical significance. Nature 567, 283 (2019).

Gelman, A. & Stern, H. The difference between significant and not significant is not itself statistically significant. Am. Stat. 60, 328–331 (2006).

Shepherd, T. G. Bringing physical reasoning into statistical practice in climate-change science. Clim. Change 169, 2 (2021).

Shepherd, T. G. et al. Storylines: an alternative approach to representing uncertainty in physical aspects of climate change. Clim. Change 151, 555–571 (2018).

Weaver, R. H. & Kysar, D. A. Courting disaster: climate change and the adjudication of catastrophe. Notre Dame Law Rev. 93, 295–356 (2017).

Hunter, D. & Salzman, J. Negligence in the air: the duty of care in climate change litigation. Univ. Pa. Law Rev. 155, 1741–1794 (2007).

Franta, B. Early oil industry knowledge of CO2 and global warming. Nat. Clim. Change 8, 1024–1025 (2018).

Supran, G. & Oreskes, N. Rhetoric and frame analysis of ExxonMobil’s climate change communications. One Earth 4, 696–719 (2021).

Bonneuil, C., Choquet, P.-L. & Franta, B. Early warnings and emerging accountability: Total’s responses to global warming, 1971–2021. Global Environ. Change 71, 102386 (2021).

Geiling, N. City of Oakland v. BP: testing the limits of climate science in climate litigation. Ecol. Law Q. 46, 683–694 (2019).

Novak, S. The role of courts in remedying climate chaos: transcending judicial nihilism and taking survival seriously. Georget. Environ. Law Rev. 32, 743–778 (2019).

Andreoni, M. Vermont to require fossil-fuel companies to pay for climate damage. New York Times https://www.nytimes.com/2024/05/31/climate/vermont-law-fossil-fuel-climate-damage.html (1 June 2024).

Karl, T. L. The perils of the petro-state: reflections on the paradox of plenty. J. Int. Aff. 53, 31–48 (1999).

Gillett, N. et al. The Detection and Attribution Model Intercomparison Project (DAMIP v1.0) contribution to CMIP6. Geosci. Model Dev. 9, 3685–3697 (2016).

Eyring, V. et al. in Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (eds Masson-Delmotte, V. et al.) 423–552 (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2021).

Kotz, M., Wenz, L., Stechemesser, A., Kalkuhl, M. & Levermann, A. Day-to-day temperature variability reduces economic growth. Nat. Clim. Change 11, 319–325 (2021).

Perkins, S. E. & Alexander, L. V. On the measurement of heat waves. J. Clim. 26, 4500–4517 (2013).

Sillmann, J., Kharin, V. V., Zhang, X., Zwiers, F. W. & Bronaugh, D. Climate extremes indices in the CMIP5 multimodel ensemble: part 1. Model evaluation in the present climate. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 118, 1716–1733 (2013).

Fischer, E. M., Sippel, S. & Knutti, R. Increasing probability of record-shattering climate extremes. Nat. Clim. Change 11, 689–695 (2021).

Wenz, L., Carr, R. D., Kögel, N., Kotz, M. & Kalkuhl, M. DOSE – global data set of reported sub-national economic output. Sci. Data 10, 425 (2023).

Lessmann, C. & Seidel, A. Regional inequality, convergence, and its determinants – a view from outer space. Eur. Econ. Rev. 92, 110–132 (2017).

Acknowledgements

We thank J. Fogel (Berkeley Judicial Institute), J. T. Laster (Delaware Court of Chancery), C. Cunningham (ret.), M. Burger (Sabin Center), J. Wentz (Sabin Center), R. Horton (Columbia University), D. Kysar (Yale Law School) and B. Franta (Oxford University) for helpful discussions, C. Smith (Vrije Universiteit Brussel) for assistance with FaIR calibration, and R. Heede (Climate Accountability Institute) for assistance with emissions data. We thank Dartmouth’s Research Computing and the Discovery Cluster for the computing resources and the World Climate Research Programme, which, through its Working Group on Coupled Modelling, coordinated and promoted CMIP6. This work was supported by National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship #1840344 to C.W.C. and by funding from Dartmouth’s Neukom Computational Institute, the Wright Center for the Study of Computation and Just Communities and the Nelson A. Rockefeller Center to J.S.M.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Both authors designed the analysis. C.W.C. performed the analysis. Both authors interpreted the results and wrote the paper.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature thanks Anders Levermann, Jing Meng, L. Merner, Kevin A. Reed and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data figures and tables

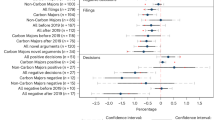

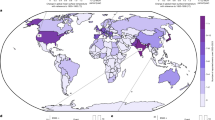

Extended Data Fig. 1 Damages when annual average temperatures are held at their observed values.

As in Fig. 2a but when emissions only affect the intensity of Tx5d values and not the annual average temperatures that moderate the effect of Tx5d. Map was generated using cartopy v0.17.0 and regional borders come from the Database of Global Administrative Areas.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Callahan, C.W., Mankin, J.S. Carbon majors and the scientific case for climate liability. Nature 640, 893–901 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-025-08751-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-025-08751-3

This article is cited by

-

Extreme weather event accountability

Nature Geoscience (2026)

-

Heatwaves linked to emissions of individual fossil-fuel and cement producers

Nature (2025)

-

Heatwaves linked to carbon emissions from specific companies

Nature (2025)

-

Ownership of power plants stranded by climate mitigation

Nature Sustainability (2025)

-

Systematic attribution of heatwaves to the emissions of carbon majors

Nature (2025)