Abstract

Midbrain dopamine neurons (DANs) signal reward-prediction errors that teach recipient circuits about expected rewards1. However, DANs are thought to provide a substrate for temporal difference (TD) reinforcement learning (RL), an algorithm that learns the mean of temporally discounted expected future rewards, discarding useful information about experienced distributions of reward amounts and delays2. Here we present time–magnitude RL (TMRL), a multidimensional variant of distributional RL that learns the joint distribution of future rewards over time and magnitude. We also uncover signatures of TMRL-like computations in the activity of optogenetically identified DANs in mice during behaviour. Specifically, we show that there is significant diversity in both temporal discounting and tuning for the reward magnitude across DANs. These features allow the computation of a two-dimensional, probabilistic map of future rewards from just 450 ms of the DAN population response to a reward-predictive cue. Furthermore, reward-time predictions derived from this code correlate with anticipatory behaviour, suggesting that similar information is used to guide decisions about when to act. Finally, by simulating behaviour in a foraging environment, we highlight the benefits of a joint probability distribution of reward over time and magnitude in the face of dynamic reward landscapes and internal states. These findings show that rich probabilistic reward information is learnt and communicated to DANs, and suggest a simple, local-in-time extension of TD algorithms that explains how such information might be acquired and computed.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$32.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 51 print issues and online access

$199.00 per year

only $3.90 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

Raw data are available in a Figshare public repository78. The Allen CCF atlas used to reconstruct the probe trajectories from histology data is available at https://mouse.brain-map.org/.

Code availability

The code used to generate the theoretical predictions, simulations and data analysis is available at https://github.com/MargaSousa/Multidimensional_dopamine_RL.git.

References

Schultz, W., Dayan, P. & Montague, P. R. A neural substrate of prediction and reward. Science 275, 1593–1599 (1997).

Sutton, R. S. & Barto, A. G. Reinforcement Learning: An Introduction 2nd edn (MIT Press, 2018).

Montague, P. R., Dayan, P. & Sejnowski, T. J. A framework for mesencephalic dopamine systems based on predictive hebbian learning. J. Neurosci. 16, 1936–1947 (1996).

Dabney, W., Rowland, M., Bellemare, M. & Munos, R. Distributional reinforcement learning with quantile regression. In Proc. 32nd AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence 2892–2901 (AAAI, 2018).

Lyle, C., Bellemare, M. G. & Castro, P. S. A comparative analysis of expected and distributional reinforcement learning. In Proc. 33rd AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence 4504–4511 (AAAI, 2019).

Bellemare, M. G., Dabney, W. & Rowland, M. Distributional Reinforcement Learning (MIT Press, 2023).

Muller, T. H. et al. Distributional reinforcement learning in prefrontal cortex. Nat. Neurosci. 27, 403–408 (2024).

Avvisati, R. et al. Distributional coding of associative learning in discrete populations of midbrain dopamine neurons. Cell Rep. 43, 114080 (2024).

Dabney, W. et al. A distributional code for value in dopamine-based reinforcement learning. Nature 577, 671–675 (2020).

Bellemare, M. G., Dabney, W. & Munos, R. A distributional perspective on reinforcement learning. Proc. Mach. Learn. Res. 70, 449–458 (2017).

Martin, J., Lyskawinski, M., Li, X. & Englot, B. Stochastically dominant distributional reinforcement learning. Proc. Mach. Learn. Res. 119, 6745–6754 (2020).

Théate, T. & Ernst, D. Risk-sensitive policy with distributional reinforcement learning. Algorithms 16, 325 (2023).

Puterman, M. L. Markov Decision Processes: Discrete Stochastic Dynamic Programming (Wiley, 2014) .

Kurth-Nelson, Z. & Redish, A. D. Temporal-difference reinforcement learning with distributed representations. PLoS ONE 4, e7362 (2009).

Fedus, W., Gelada, C., Bengio, Y., Bellemare, M. G. & Larochelle, H. Hyperbolic discounting and learning over multiple horizons. Preprint at https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1902.06865 (2019).

Janner, M., Mordatch, I. & Levine, S. Gamma-models: generative temporal difference learning for infinite-horizon prediction. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 33 (NeurIPS 2020) (eds Larochelle, H. et al.) 1724–1735 (Curran Associates, 2020).

Thakoor, S. et al. Generalised policy improvement with geometric policy composition. Proc. Mach. Learn. Res. 162, 21272–21307 (2022).

Shankar, K. H. & Howard, M. W. A scale-invariant internal representation of time. Neural Comput. 24, 134–193 (2012).

Tano, P., Dayan, P. & Pouget, A. A local temporal difference code for distributional reinforcement learning. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 33 (NeurIPS 2020) (eds Larochelle, H. et al.) 13662–1367 (Curran Associates, 2020).

Tiganj, Z., Gershman, S. J., Sederberg, P. B. & Howard, M. W. Estimating scale-invariant future in continuous time. Neural Comput. 31, 681–709 (2019).

Barlow, H. B & Rosenblith, W. A. in Sensory Communication (ed. Rosenblith, W. A.) 217–234 (MIT Press, 1961).

Laughlin, S. A simple coding procedure enhances a neuron’s information capacity. Z. Naturforsch. C 36, 910–912 (1981).

Simoncelli, E. P. & Olshausen, B. A. Natural image statistics and neural representation. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 24, 1193–1216 (2001).

Fairhall, A. L., Lewen, G. D., Bialek, W. & de Ruyter Van Steveninck, R. R. Efficiency and ambiguity in an adaptive neural code. Nature 412, 787–792 (2001).

Lau, B. & Glimcher, P. W. Dynamic response-by-response models of matching behavior in rhesus monkeys. J. Exp. Anal. Behav. 84, 555–579 (2005).

Rudebeck, P. H. et al. A role for primate subgenual cingulate cortex in sustaining autonomic arousal. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 111, 5391–5396 (2014).

Cash-Padgett, T., Azab, H., Yoo, S. B. M. & Hayden, B. Y. Opposing pupil responses to offered and anticipated reward values. Anim. Cogn. 21, 671–684 (2018).

Ganguli, D. & Simoncelli, E. P. Efficient sensory encoding and bayesian inference with heterogeneous neural populations. Neural Comput. 26, 2103–2134 (2014).

Louie, K. Asymmetric and adaptive reward coding via normalized reinforcement learning. PLoS Comput. Biol. 18, e1010350 (2022).

Schütt, H. H., Kim, D. & Ma, W. J. Reward prediction error neurons implement an efficient code for reward. Nat. Neurosci. 27, 1333–1339 (2024).

Kahneman, D. & Tversky, A. Prospect theory: an analysis of decision under risk. Econometrica 47, 363–391 (1979).

Dayan, P. Improving generalization for temporal difference learning: the successor representation. Neural Comput. 5, 613–624 (1993).

Brunec, I. K. & Momennejad, I. Predictive representations in hippocampal and prefrontal hierarchies. J. Neurosci. 42, 299–312 (2022).

Yamada, H., Tymula, A., Louie, K. & Glimcher, P. W. Thirst-dependent risk preferences in monkeys identify a primitive form of wealth. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 110, 15788–15793 (2013).

Stauffer, W. R., Lak, A. & Schultz, W. Dopamine reward prediction error responses reflect marginal utility. Curr. Biol. 24, 2491–2500 (2014).

Kacelnik, A. & Bateson, M. Risky theories—the effects of variance on foraging decisions. Am. Zool. 36, 402–434 (1996).

Yoshimura, J., Ito, H., Miller III, D. G. & Tainaka, K.-I. Dynamic decision-making in uncertain environments: I. The principle of dynamic utility. J. Ethol. 31, 101–105 (2013).

Kagel, J. H., Green, L. & Caraco, T. When foragers discount the future: constraint or adaptation? Anim. Behav. 34, 271–283 (1986).

Soares, S., Atallah, B. V. & Paton, J. J. Midbrain dopamine neurons control judgment of time. Science 354, 1273–1277 (2016).

Behrens, T. E. J., Woolrich, M. W., Walton, M. E. & Rushworth, M. F. S. Learning the value of information in an uncertain world. Nat. Neurosci. 10, 1214–1221 (2007).

Soltani, A. & Izquierdo, A. Adaptive learning under expected and unexpected uncertainty. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 20, 635–644 (2019).

Nassar, M. R. et al. Rational regulation of learning dynamics by pupil-linked arousal systems. Nat. Neurosci. 15, 1040–1046 (2012).

Sharpe, M. J. et al. Dopamine transients do not act as model-free prediction errors during associative learning. Nat. Commun. 11, 106 (2020).

Engelhard, B. et al. Specialized coding of sensory, motor and cognitive variables in VTA dopamine neurons. Nature 570, 509–513 (2019).

Sharpe, M. J. et al. Dopamine transients are sufficient and necessary for acquisition of model-based associations. Nat. Neurosci. 20, 735–742 (2017).

Jeong, H. et al. Mesolimbic dopamine release conveys causal associations. Science 378, eabq6740 (2022).

Coddington, L. T. & Dudman, J. T. The timing of action determines reward prediction signals in identified midbrain dopamine neurons. Nat. Neurosci. 21, 1563–1573 (2018).

Tesauro, G. Practical issues in temporal difference learning. Mach. Learn. 8, 257–277 (1992).

Bornstein, A. M. & Daw, N. D. Multiplicity of control in the basal ganglia: computational roles of striatal subregions. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 21, 374–380 (2011).

Yin, H. H. et al. Dynamic reorganization of striatal circuits during the acquisition and consolidation of a skill. Nat. Neurosci. 12, 333–341 (2009).

Hamid, A. A., Frank, M. J. & Moore, C. I. Wave-like dopamine dynamics as a mechanism for spatiotemporal credit assignment. Cell 184, 2733–2749 (2021).

Cruz, B. F. et al. Action suppression reveals opponent parallel control via striatal circuits. Nature 607, 521–526 (2022).

Lee, R. S., Sagiv, Y., Engelhard, B., Witten, I. B. & Daw, N. D. A feature-specific prediction error model explains dopaminergic heterogeneity. Nat. Neurosci. 27, 1574–1586 (2024).

Takahashi, Y. K. et al. Dopaminergic prediction errors in the ventral tegmental area reflect a multithreaded predictive model. Nat. Neurosci. 26, 830–839 (2023).

Balsam, P. D. & Gallistel, C. R. Temporal maps and informativeness in associative learning. Trends Neurosci. 32, 73–78 (2009).

International Brain Laboratory. Behavior, Appendix 1: IBL protocol for headbar implant surgery in mice. Figshare https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.11634726.v5 (2020).

Uchida, N. & Mainen, Z. F. Speed and accuracy of olfactory discrimination in the rat. Nat. Neurosci. 6, 1224–1229 (2003).

Lopes, G. et al. Bonsai: an event-based framework for processing and controlling data streams. Front. Neuroinform. 9, 7 (2015).

Siegle, J. H. et al. Open ephys: an open-source, plugin-based platform for multichannel electrophysiology. J. Neural Eng. 14, 045003 (2017).

Bell, A. J. & Sejnowski, T. J. An information-maximization approach to blind separation and blind deconvolution. Neural Comput. 7, 1129–1159 (1995).

Hyvarinen, A. Fast and robust fixed-point algorithms for independent component analysis. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. 10, 626–634 (1999).

Kvitsiani, D. et al. Distinct behavioural and network correlates of two interneuron types in prefrontal cortex. Nature 498, 363–366 (2013).

Hill, D. N., Mehta, S. B. & Kleinfeld, D. Quality metrics to accompany spike sorting of extracellular signals. J. Neurosci. 31, 8699–8705 (2011).

Ludvig, E. A., Sutton, R. S. & Kehoe, E. J. Stimulus representation and the timing of reward-prediction errors in models of the dopamine system. Neural Comput. 20, 3034–3054 (2008).

Rowland, M. et al. Statistics and samples in distributional reinforcement learning. Proc. Mach. Learn. Res. 97, 5528–5536 (2019).

Newey, W. K. & Powell, J. L. Asymmetric least squares estimation and testing. Econometrica 55, 819–847 (1987).

Brunel, N. & Nadal, J.-P. Mutual information, fisher information, and population coding. Neural Comput. 10, 1731–1757 (1998).

Glimcher, P. W. & Fehr, E. Neuroeconomics: Decision Making and the Brain (Academic Press, 2013).

Eshel, N., Tian, J., Bukwich, M. & Uchida, N. Dopamine neurons share common response function for reward prediction error. Nat. Neurosci. 19, 479–486 (2016).

Cohen, J. Y., Haesler, S., Vong, L., Lowell, B. B. & Uchida, N. Neuron-type-specific signals for reward and punishment in the ventral tegmental area. Nature 482, 85–88 (2012).

Lee, K. et al. Temporally restricted dopaminergic control of reward-conditioned movements. Nat. Neurosci. 23, 209–216 (2020).

Stauffer, W. R., Lak, A., Kobayashi, S. & Schultz, W. Components and characteristics of the dopamine reward utility signal. J. Comp. Neurol. 524, 1699–1711 (2016).

Kobayashi, S. & Schultz, W. Influence of reward delays on responses of dopamine neurons. J. Neurosci. 28, 7837–7846 (2008).

Mathis, A., Mamidanna, P. & Cury, K. M. Deeplabcut: markerless pose estimation of user-defined body parts with deep learning. Nat. Neurosci. 21, 1281–1289 (2018).

Yagle, A. E. Regularized matrix computations. Preprint at https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:7810635 (2005).

Chakravarti, N. Isotonic median regression: a linear programming approach. Math. Oper. Res. 14, 303–308 (1989).

Picheny, V., Moss, H., Torossian, L. & Durrande, N. Bayesian quantile and expectile optimisation. Proc. Mach. Learn. Res. 180, 1623–1633 (2022).

Sousa, M. et al. A multidimensional distributional map of future reward in dopamine neurons. Figshare https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.28390151.v1 (2025).

Acknowledgements

We thank H. Schuett, K. Lloyd, F. Rodrigues, T. Duarte and C. Haimerl for comments on versions of the manuscript and the entire J.J.P. laboratory, past and present, for feedback during the course of this project. The work was funded by an HHMI International Research Scholar Award to J.J.P. (55008745), a European Research Council Consolidator grant (DYCOCIRC-REP-772339-1) to J.J.P., a Bial bursary for scientific research to J.J.P. (193/2016), a US National Institutes of Health grant (NIH U19 NS107616) to K.L., internal support from the Champalimaud Foundation, and PhD fellowships from Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia to M.S. (PD/BD/141552/2018) and B.F.C. (PD/BD/105945/2014). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.S. developed the theory, together with J.J.P. and D.C.M., and with input from K.L. The experiments were designed by J.J.P., M.S. and B.F.C. The experimental apparatus was constructed by B.F.C., P.B. and M.S. All behavioural and electrophysiological experiments that provided data for the study were performed by P.B., and B.F.C. performed pilot experiments to establish protocols. P.B. and M.S. analysed histological data. M.S. analysed the neural and behavioural data, with input from B.F.C., K.L. and D.C.M. M.S. performed the foraging simulations with input from D.C.M. and K.L. J.J.P. and M.S. wrote the paper, and D.M., K.L. and B.F.C. edited it. J.J.P. supervised all aspects of the project.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature thanks Will Dabney and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data figures and tables

Extended Data Fig. 1 Histological reconstruction of recording sites and photo-identification of DANs.

a, Recording locations of the probe tracks. Recording sites from all mice in seven coronal sections from the rostrocaudal axis (AP −2.68, −2.76, −2.84, −2.92, −3.05, −3.13, −3.17). The approximate location of the photo-identified neurons is depicted in green, the VTA has a red outline and the SNc a blue outline. Software from the Cortex lab repository (https://github.com/cortex-lab/allenCCF) was used to produce this figure. b, Three example photo-identified neurons. Left: Raster plot with single spikes aligned to laser pulse onset (10 ms duration, represented in blue). Right: Distribution of latencies to first spike after laser pulse observed in a 1–20-ms window. Inset: mean waveform (black) and mean laser-triggered waveform (blue). c–h, Distribution of the probability of observing a spike between 1 and 10 ms after laser onset pulse (c), median latency to first spike over a window spanning from 1 ms and 20 ms (d), differences in firing rate between the baseline and 1–10-ms post-pulse window (e), log of the P value of the salt test (f), correlation coefficient between the mean waveform and the mean laser-triggered waveform (g) and log of t-test for the difference in firing rates between baseline and post-pulse firing rate in a 1–10 ms window. (h). Data underlying the figure can be found in the Supplementary Data.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Hierarchical clustering of VTA and SNc neurons.

a, AuROC aligned to cue and reward delivery for the recorded population of neurons. Pink corresponds to increase relative to baseline activity, green to decrease and black to no change. The blue dots correspond to photo-identified neurons. b, Projection coefficient for the three first PCs of the auROC. c, Using these projection coefficients, hierarchical clustering with the Euclidean distance was performed with the complete agglomeration method. Top: Each dot corresponds to a recorded neuron in the three first PC space. d, Left: PSTH for each cluster, aligned to the cues predicting different reward delays. The shaded area represents the standard error of the mean across neurons. Right: PSTH for each cluster, aligned to reward delivery for different reward amounts. Shaded area represents s.e.m. across neurons. Data underlying the figure can be found in the Supplementary Data.

Extended Data Fig. 3 Replicating the main findings for photo-identified and non-photo-identified putative DANs.

a–e, Analysis from Fig. 3 with n = 122 photo-identified and non-photo-identified putative DANs. b, Mean correlation coefficient r=0.91 and geometric mean of the two-tailed t-test p-values (p-value=6.57e-48, n=10,000 partitions). Inset: the histogram of the regression slopes, 95% CI=(0.99,1.01). The error bars in c represent the 99% CI of the cross validation of temporal discount factors of single neurons using 50% of the total number of trials per delay n = 10,000 times. f, Estimated single-neuron temporal discount factors as a function of the position in the ML axis. Dots are colour-coded by mouse identity and dots with a blue outer circle correspond to the photo-identified neurons. The line represents the Huber Regression fit. Spearman rank correlation over neurons, two-tailed test p-value=0.26, n=86. g,h,k, Analysis from Fig. 4 with n = 122 photo-identified and non-photo-identified putative DANs. g, Pearson correlation coefficient over neurons r=0.2, two-tailed test n=98, p-value=0.0486, 95% CI=(-0.007,0.38). i,j,l,m, Analysis from Fig. 5 with n = 122 photo-identified and non-photo-identified putative DANs. i, Pearson correlation coefficient over n=98 neurons r=-0.65, two-tailed t-test p-value=1.14e-13, 95% CI=(-0.75,-0.52). j, Bootstrapped 10,000 times to test if variance of corrected firing rate for variable cue is greater than for certain cue: one-tailed p-value=0.093, n=122 neurons, mean difference in the variances=0.020, 95% CI=(-0.0053,0.089). l, Bootstrapped 10,000 times testing if update in temporal discount when removing the shortest or longest delay is different over neurons: two-tailed p-value=0.07, n=122, mean absolute difference=0.04, 95% CI=(0.0015, 0.11). m, Pearson correlation coefficient over neurons r=-0.47, two-tailed t-test p-value= 6.74e-08, n=122, 95% CI=(-0.6,-0.31). Data underlying the figure can be found in the Supplementary Data.

Extended Data Fig. 4 Replicating the main findings for individual mice.

a–c, Analysis from Fig. 3a–c, colour-coded by mouse. In b, p-value=3.33e-5 for mouse 3353 and p-value=2.02e-5 for mouse 4098. The error bars in c represent the 99% CI of the cross validation of temporal discount factors of single neurons using 50% of the total number of trials per delay n=10,000 times. d,e, Decoded density using the dopamine population responses from mice 3353 and 4098. f, Analysis from Fig. 4c for neurons collected from mouse 3353. g, Analysis from Fig. 4a colour-coded by mouse. For mouse 3353: Pearson correlation coefficient r=0.49, two-tailed test n=14, p-value=0.073, 95% CI=(-0.05,0.81). h, Analysis from Fig. 5c colour-coded by mouse. Mouse 3353: Pearson correlation coefficient r=-0.88, two-tailed test p-value=0.0, n=14, 95% CI=(-0.96,-0.66). Mouse 4098: Pearson correlation coefficient r=-0.47, two-tailed test p-value=0.24, n=8, 95% CI=(-0.88,0.35). i, Analysis from Fig. 5d colour-coded by mouse. Bootstrapped 10,000 times to test if variance of reversal points for variable cue is greater than for certain cue: for mouse 3353 one-tail p-value=0.14, n=17, mean difference in the variances=0.016, 95% CI=(-0.0082,0.083) and for mouse 4098 one-tail p-value=0.071, n=12, mean difference in the variances=0.17, 95% CI=(-0.0051,0.66). The significance level was not corrected for multiple comparisons. j, Decoded density over magnitudes from the population of DANs from mouse 3353 for the variable and certain cues. k, Analysis from Fig. 5g colour-coded by mouse. Bootstrapped 10,000 times testing if update in temporal discount when removing the shortest or longest delay is different: for mouse 3353 two-tailed p-value=0.0013, n=17, mean absolute difference=0.20, 95% CI=(0.041, 0.37) and for mouse 4098 two-tailed p-value=0.0083, n=12, mean absolute difference=0.17, 95% CI=(0.014, 0.36). l, Analysis from Fig. 5h colour-coded by mouse. For mouse 3353: Pearson correlation coefficient r=-0.64, two-tailed test p-value=0.006, n=17, 95% CI=(-0.85,-0.23). For mouse 4098: Pearson correlation coefficient r=-0.025, two-tailed test p-value=0.94, n=12, 95% CI=(-0.59,0.56). Data underlying the figure can be found in the Supplementary Data.

Extended Data Fig. 5 Testing the influence of the number and type of delays experienced on estimated temporal discounts.

a–c, Similar to Fig. 3a–c but not considering the responses to the 0-s delay. The error bars in c represent the 99% CI of the cross validation of temporal discount factors of single neurons using 50% of the total number of trials per delay n=10,000 times. d, Responses at the reward delivery after the 6-s delay as a function of the responses at the 0-s cue. The dashed line represents the unitary line. e,f, Similar to Fig. 3b,c but considering the responses at the 6-s reward as an (under) estimator of the 0-s cue responses, for neurons recorded from the mice only subjected to three delays. In e, p-value=2.9e-18. The error bars in f represent the 99% CI of the cross validation of temporal discount factors of single neurons using 50% of the total number of trials per delay n=10,000 times. Data underlying the figure can be found in the Supplementary Data.

Extended Data Fig. 6 The first-phase responses of midbrain DANs encode a distribution that is similar across cues and closer to the prior distribution of the rewards in the task than would be expected by chance.

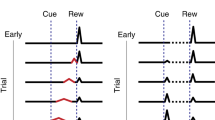

a, Raster aligned to odour valve opening for two example neurons. The green shaded area depicts the window used to compute the first-phase responses (50–200 ms) and the blue to the second phase (300–450 ms). b, Second-phase responses vary more with the upcoming delay than first-phase responses. First-phase mean responses across the 1.5-s, 3-s and 6-s cues for different neurons as a function of the second-phase mean responses. The slopes are the fitted linear regression models for each neuron. Points and slopes are colour-coded by the estimated temporal discount factor. Inset: distribution of slopes across neurons. The variation in first-phase responses is smaller than in second-phase responses, because the mean absolute slope (vertical line) is smaller than one: two-tailed p-value=0.001, 95% CI =(0.0099,0.71) bootstrapped n=10,000 times. c, Decoded joint density of reward over magnitude and time, using the first (left) and second (right) phase population responses aligned to the different cues. d, Decoded density over reward time using the first-phase dopamine population responses for all cues. The grey lines depict the decoded density when the population temporal discount factors are shuffled. The light lines represent decoded densities using the responses of 70% of randomly selected trials and the thicker lines represent the mean decoded densities. e, 90% CI of the mean Kullback–Leibler (KL) divergence between the true prior distribution of reward times and magnitudes in the task and the distribution decoded from DAN activity. This comparison considers population tuning for reward time and magnitude, either preserved or shuffled, across 100 decoder runs. Data underlying the figure can be found in the Supplementary Data.

Extended Data Fig. 7 Decoding distribution over reward magnitudes.

a, Responses for different reward amounts for individual DANs sorted by estimated reversal point. b, Bias in the estimation of optimism level as a function of reversal point, computed with Monte Carlo simulations. c, Variance in the estimation of optimism level as a function of reversal point, computed with Monte Carlo simulations. d, Distribution of the difference between the reversal point estimated at reward and at the cue, computed using the linear regression depicted in Fig. 4a. e, Corrected asymmetry as a function of the reversal point estimated at the reward, colour-coded by the confidence. The dashed line represents the isotonic regression fit. f, Corrected asymmetry as a function of the reversal point estimated at the cue, colour-coded by the confidence. The dashed line corresponds to the isotonic regression fit. Data underlying the figure can be found in the Supplementary Data.

Extended Data Fig. 8 Efficient coding predictions and adaptation of DAN population temporal discount factors with reward occurrence rate.

a, Densities after removing the shortest (green) or longest (pink) reward delay. b, Optimized tuning functions for the densities of reward time depicted in a. c, Fisher information for the optimized populations. d, Considering exponential decaying kernels with different time constants to estimate the rate of reward occurrence, we computed the p-value bootstrapping 10,000 times, for the null hypothesis that the temporal discounts for higher reward rates are shallower or equal to the lower reward rates. Horizontal blue line: p-value significance equal to 0.1. Data underlying the figure can be found in the Supplementary Data.

Extended Data Fig. 9 At a population level, the distributions over temporal discounts and reversal points are statistically independent.

However, in principle, the joint distribution can be decoded without assuming factorization over time and magnitude. a, Estimated reversal points as a function of estimated temporal discount factors, for photo-identified and putative DANs. Only neurons with reversal points in the range of reward magnitudes given in the experiment (1 μl–8 μl) were included. The p-value refers to the chi-squared test, considering the null hypothesis that the joint distribution over the temporal discounts and reversal points is equal to the product of the marginals, considering 16 degrees of freedom, n=122, χ2=27.86. b, We simulate a population of n=100 units with a diverse set of temporal discount (γ) and reversal points uniformly sampled, and decode the reward distribution over magnitude and time (not assuming these features are independent), from the responses at the cue. Importantly, these simulations were done for the cue that predicts a variable amount after a delay of 3 s. We first apply the inverse Laplace for each reversal point and get the temporal evolution of reversal points (middle). Then, for each time we decode the distribution over reward magnitudes (lower), by dividing the probability for each time point by one minus of probability of reward=0. c, The same simulations but for all cues, as described in Fig. 4. Data underlying the figure can be found in the Supplementary Data.

Extended Data Fig. 10 A foraging mouse must decide which patch to choose to maximize cumulative collected rewards in a non-stationary environment.

a, Axes indicate the learnt joint probability distribution of reward time and magnitude associated with each patch. Rewards available from the three patches are dynamic during the day: patch one provides lower reward magnitudes early in the day. Patch two provides variable reward magnitudes with the same mean as patch one early in the day. Patch three provides bigger reward magnitudes than either patch one or patch two, but later in the day. b, In the agent making use of SR, the value of each patch at the start of the day is the product of the temporally discounted future occupancy, learnt through a temporal-difference algorithm, by the reward at each future time step. In the agent making use of TMRL, the probability distribution over future reward time and magnitude is weighted by a utility function to obtain an estimate that depends on internal state or/and the dynamics of the environment (see Methods for a detailed description). The utility is represented using a colour gradient, ranging from low (black) to high (yellow). c, Adaptation of SR and TMRL agents when the timescale of the environment changes, from dusk to dawn. The SR future occupancy has to be relearnt, considering a lower temporal discount factor. The TMRL utility function discounts the reward time more steeply at dawn. d, Illustration of how the SR and the TMRL adapt when reward is over-valued, that may occur for example when the mouse is sated and becomes hungry. For the SR agent, the reward signal increases. For the TMRL agent, the utility function over reward magnitudes is linear when the mouse is sated and becomes convex when the mouse is hungry. e, When the mouse is hungry and has less time to forage at dawn, it may become more risk prone. The SR agent has to relearn the future occupancy and over-value the reward. The TMRL utility function, in addition to discounting the reward time more steeply at dawn, will apply a convex function to reward magnitudes. f, Probability of choosing the optimal patch (patch 1 or 2) at the first trial after dawn for the three algorithms. g, Probability of choosing the optimal patch (patch 2) at the first trial after being hungry for the three algorithms. h, Probability of choosing the optimal patch (patch 2) at the first trial after dawn for the three algorithms when the agent is hungry. i, Value of each patch as a function of the time since dawn for standard TDRL, SR and TMRL. The error bars represent the standard deviation over 10 runs and the lines represent the mean. j, Value of each patch as a function of the time since the mouse is hungry. k, Value of each patch as a function of the time since dawn when the mouse is hungry. Data underlying the figure can be found in the Supplementary Data.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

This file contains: Supplementary Table 1: a description of the number of photo-identified neurons recorded per mouse and session; an explanation of how the number of experienced delays influences the estimation of temporal discount factors; and a description of the statistical tests conducted to assess the adaptation of temporal discount factors to changes in reward-time statistics.

Supplementary Data

Source Data for Figures 1–5 and Extended Data Figures 1–10.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Sousa, M., Bujalski, P., Cruz, B.F. et al. A multidimensional distributional map of future reward in dopamine neurons. Nature 642, 691–699 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-025-09089-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-025-09089-6

This article is cited by

-

How dopamine neurons devalue delayed rewards

Nature (2025)

-

Reconciling time and prediction error theories of associative learning

Nature Communications (2025)